#raymond lully

Text

[Monograph on Raymond Lully's Ars magna generalis (Nîmes, 1906).]

#s07e13 legacies#guy fieri#guyfieri#diners drive-ins and dives#ars magna generalis#raymond lully#nîmes#monograph

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

If literature were nothing more than verbal algebra, anyone could produce any book by essaying variations. The lapidary formula ‘Everything flows’ abbreviates in two words the philosophy of Heraclitus: Raymond Lully would say that, with the first word given, it would be sufficient to essay the intransitive verbs to discover the second and obtain, thanks to methodical chance, that philosophy and many others. Here it is fitting to reply that the formula obtained by this process of elimination lacks all value, and even meaning; for it to have some virtue, we must conceive it in terms of Heraclitus, in terms of an experience of Heraclitus, even though ‘Heraclitus’ is nothing more than the presumed subject of that experience. I have said that a book is a dialogue, a form of relationship; in a dialogue an interlocutor is not the sum or average of what he says: he may not speak and still reveal that he is intelligent, he may admit intelligent observations and reveal his stupidity.

(Borges, from "A Note on (towards) Bernard Shaw," trans. James E. Irby)

#important to dogear bits you can just read at AI Guys. 'essaying' is generally the sort of verb that makes them cower#apologies to Herakleitos and to Ramon Llull#and you know. i think there is like actually truly a conversation about AI writing as potentially a kind of parasocial literature:#a relationship which only exists in its reception. something something idealism#chatgpt is a realdoll pass it on

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

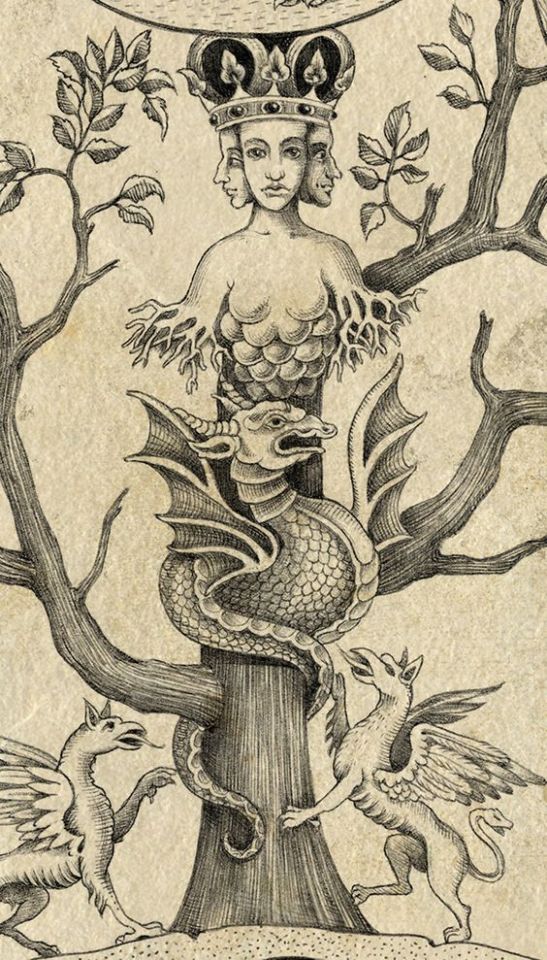

Raymond Lully, who was one of the great early alchemists, once pointed out that alchemical transmutation was impossible unless the alchemist 'Himself' was in the process of transformation.

~Manly P. Hall

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Marche des rois - Chant trad. provençale repris par Bizet dans L'Arlésienne (partition,sheet music)

La Marche des rois - Chant trad. provençale repris x Bizet dans L'Arlésienne (partition,sheet music) Easy Piano Solo arr.

https://youtu.be/KsDBOdWDRwQ

The March of the Kings or The March of the Three Kings or, in Provençal, La Marcho di Rèi is a popular Christmas carol of Provençal origin celebrating Epiphany and the Three Kings. Its revival by Georges Bizet for his Arlésienne popularized the theme.

The precise origins of both the tune and the lyrics are uncertain and debated.

The words are regularly attributed to Joseph-François Domergue (1691-1728), priest-dean of Aramon, in the Gard, from 1724 to 1728, whose name appears on the first manuscript copy dated 1742 and kept at the library of Avignon.

The text is published in the Compendium of Provençal and Francois Spiritual Songs engraved by Sieur Hue published in 1759. Subsequently, the work was included in the various editions of the Provençal Christmas collection by the poet and composer of the 17th century Nicolas Saboly (1614-1675) to which it has often — and erroneously — been attributedNote.

According to the 1742 document, the song uses the air of a Marche de Turenne1. This mention corresponds to the established practice of noëlistes consisting in placing their texts on “known” French songs spread by the printing press. One hypothesis is that this Marche de Turenne would be a military march dating back to the 17th century, in honor of the victories of Marshal de Turenne, which some authors wanted to attribute to Lully, although no document corroborates this attribution.

An Avignon tradition rather dates the Marche de Turenne back to the 15th century, at the time of King René (1409-1480) while certain authors from the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century leaned towards a reference to Raymond de Turenne (1352 -1413), known as Le Fléau de Provence, grandnephew of Pope Clement VI and nephew of Pope Gregory XI.

In the 21st century, several American researchers postulate that the March of the Kings has a medieval origin dating back to the 13th century; it could then be one of the oldest Christmas carols listed with Veni redemptor gentium, and perhaps the first entirely composed in the vernacular language, and not in Latin.

According to research carried out by the scholar Stéphen d'Arve at the end of the 19th century, the only known score is that of Étienne-Paul Charbonnier (1793-1872), organist at the cathedral of Aix-en-Provence , who — perhaps taking it from the chain of its predecessors — had reconstructed it from memory, modifying its orchestration as new instruments were introduced.

Henri Maréchal, an inspector of the Conservatoires de France who did research at the request of Frédéric Mistral, thought, for his part, that 'La Marcha dei Rèis' must have been composed by the Abbé Domergue himself.

Covers and adaptations

The March of the Kings is one of the themes of the overture to L'Arlésienne (1872), incidental music composed by Georges Bizet for a drama on a Provençal subject by Alphonse Daudet.

According to the musicologist Joseph Clamon, Bizet was able to find the melody of this march in a book published in 1864. After the failure of the drama, Bizet drew from incidental music a suite for orchestra (Suite no 1) which met with immediate success.

In 1879, four years after the composer's death, his friend Ernest Guiraud produced a second suite (Suite no 2) in which the March of the Kings is taken up in canon in the last part of the revised work.

Certain passages are also found in Edmond Audran's operetta Gillette de Narbonne, created in 188219. The words of a song 'M'sieu d'Turenne', which can be sung to the tune of the March of the Kings, are due to Léon Durocher (1862-1918).

The March of the Kings has become a traditional French song and one of the most common Christmas carols in the repertoire of French-speaking choirs. It has had several covers by performers such as Tino Rossi, Les Quatre Barbus, Marie Michèle Desrosiers or, in English, Robert Merrill. The piece has been adapted many times, notably by the organist Pierre Cochereau through an improvised toccata in 1973 for the Suite à la Française on popular themes.

Read the full article

0 notes

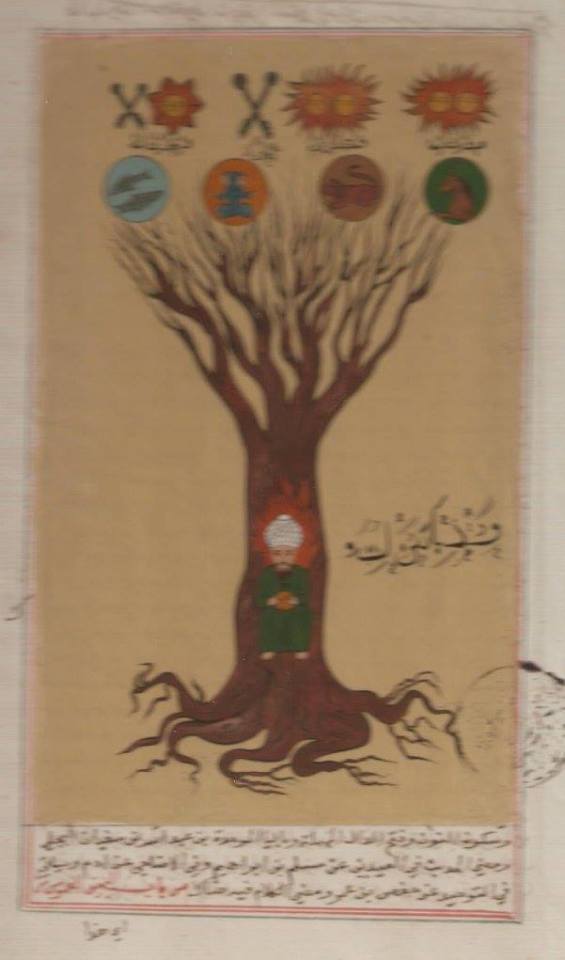

Photo

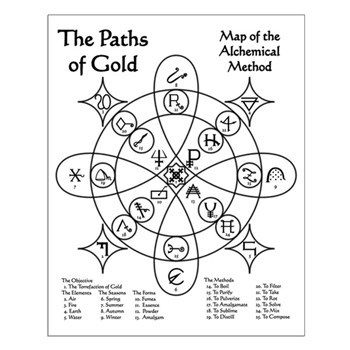

Sufi alchemical diagram that Raymond Lully copied.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is your son texting about Ramon Llull?

(Mem de catalinsicatalines a l'instagram)

#ramon llull#humor#literatura#catalan literature#literatura catalana#raymond lully#raimundus lullius

53 notes

·

View notes

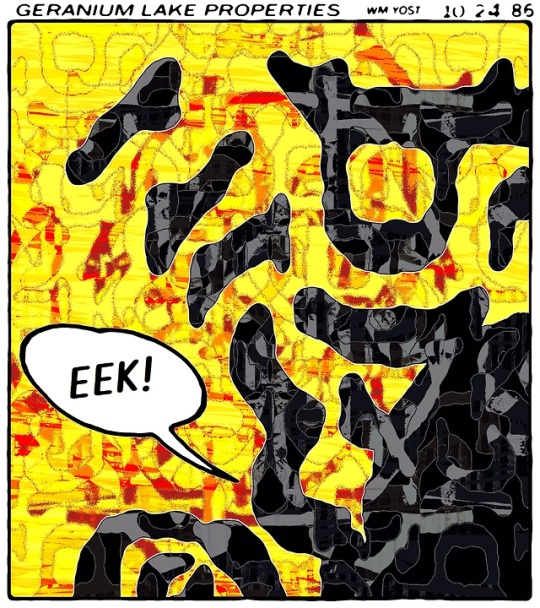

Photo

Bagri Maro and the Matacaballos

Lin Tarczynski

2018

Bagri Maro is the hero of Tales of a Horse Scorpion, a series of novels by Raymond Lully. The setting of the novels is a future Earth where humans have become extinct and the world is dominated by five races of intelligent arthropods. Wm. Yost said he encountered the work of Raymond Lully in his early teens, when he saw the novels in a comic book, in a depiction of Dr. Strange's library by Steve Ditko.

#bagri maro#geranium lake properties#abstract comics#asemic writing#lin tarczynski#raymond lully#glp#lcmt

3 notes

·

View notes

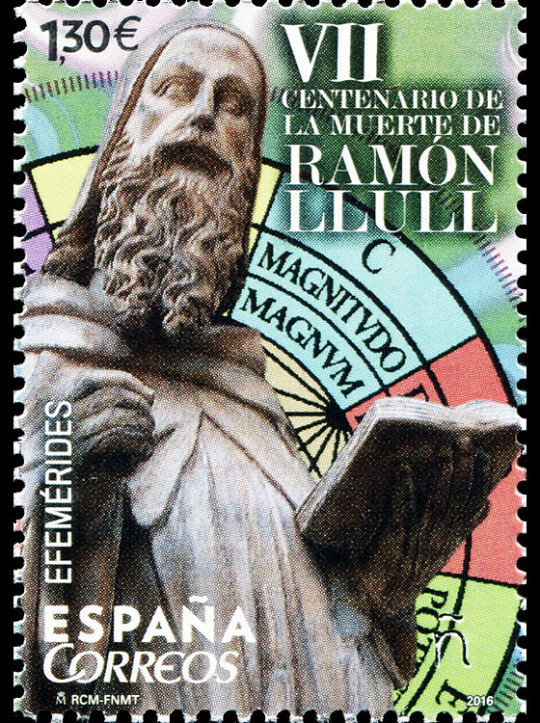

Photo

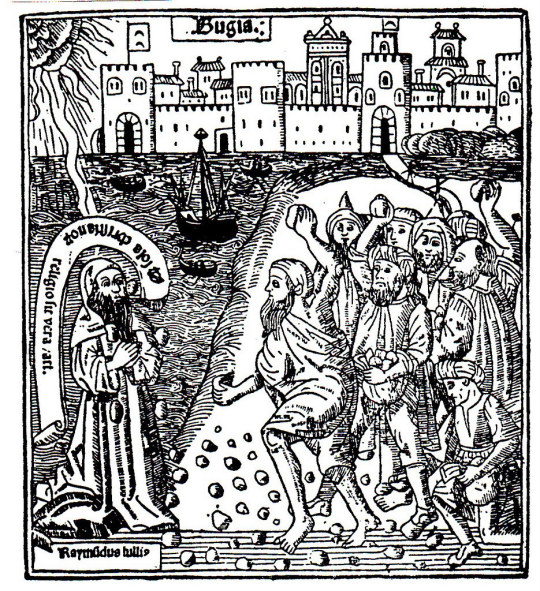

Descansi en pau, Ramon Llull. One of the most accomplished minds of the Middle Ages, especially in light of recent discoveries of some of his lost manuscripts which predated by many centuries various eclectic philosophical works, Llull was born in Majorca and is credited with creating the first major work of Catalan literature. He was thought to have died on this date in 1315 in his early 80s after being stoned by an angry crowd in North Africa (although the date is now disputed).

Stamp details:

Issued on: April 12, 2016

From: Madrid, Spain

MC #5064

#Ramon Llull#Raymond Lully#Raymond Lull#Raymundus Lullus#spain#stamps#philately#june 29#رامون لول#Raymond Lulle#Raimundo Lulio#Doctor Illuminatus#Third Order of St. Francis#España#Majorca#Regne de Mallorca#Reino de Mallorca#catalan

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

AVRUPA’NIN İLK SİMYACILARI

İlk Haçlı Seferleri döneminde simya, merkezini Moors tarafından tanıtıldığı İspanya'ya kaydırdı. On ikinci yüzyılda Artephius, 'İnsan Yaşamını Uzatma Sanatı’'nı yazdı ve bin yıllık bir süre boyunca yaşadığı bildiriliyor. Bunu kendisi de teyit ediyor:

"Ben, Artephius, Hermes'in kitabındaki tüm sanatı öğrenmiş olarak, bir zamanlar diğerleri gibi, kıskançtım, ama şimdi bin yıl ya da o civarlarda yaşadım (ki bu, Tanrı'nın lütfuyla doğduğumdan beri üzerimden bin yıl geçti) ve bu takdire şayan özün kullanımı, gördüğüm gibi, bu uzun zaman dilimi boyunca, insanların, acıma ve iyilikle hareket eden filozofların sözlerinin belirsizliği nedeniyle aynı büyüyü mükemmelleştirmeyi başaramadıklarını gördüm. Bu son günlerimde, insanların bu eserle ilgili daha fazla arzulayacak bir şeyleri kalmaması için, tüm samimiyetimle ve gerçekten yayınlamaya karar verdim. Yazmamın yasal olmadığı tek bir şey dışında, çünkü bu gerçekten yalnızca Tanrı veya bir efendi tarafından ifşa edilebilir. Yine de, bu aynı şekilde, kişinin dik kafalı olmaması ve biraz tecrübe sahibi olması koşuluyla, bu kitaptan öğrenilebilir.”

On üçüncü yüzyıl edebiyatından 'Tesero' adlı bir eser 1272'de Kastilya Kralı Alphonso'ya atfedildi: William de Loris, 1282'de 'Le Roman de Rose'u yazdı, Jean de Meung'un yardımıyla, aynı zamanda 'İtiraz'ı da yazdı. Gezici Simyacıya Doğanın Öyküsü' ve 'Simyacının Doğaya Yanıtı'. 1250'de Padua yakınlarında doğan Peter d'Apona, 'sihir' üzerine birkaç kitap yazdı ve Engizisyon tarafından, kendisine yedi liberal sanat ve bilimi öğreten, her biri kristal bir kap içinde bulunan yedi ruha sahip olmakla suçlandı. Acıyla öldü.

Bu dönem hakkında ortaya çıkan diğer ünlü isimler arasında, en ünlü eseri 'Theatrum Chemicum'da bulunan Arnold de Villeneuve veya Villanova'dır. Paris'te tıp okudu ama aynı zamanda bir ilahiyatçı ve simyacıydı. Arkadaşı Peter d'Apona gibi, bilgisini şeytandan aldığı düşünülüyordu ve birçok kişi tarafından büyülü uygulamalarla suçlandı. Kendisi Engizisyon'un eline geçmemiş olmasına rağmen, kitapları sapkın içeriklerinden dolayı bu kurum tarafından Tarragona'da yakılmaya mahkûm edildi. Villanova, inanç ve hayır işlerinin Tanrı'nın gözünde Kurban Ayini'nden daha kabul edilebilir olduğunu ileri sürdü!

Albertus Magnus'un (1234-1314) otoritesine kuşkusuz saygı duyulmalıdır, çünkü uzun bir yaşamın büyük bir bölümünü bir manastırda inzivada felsefe çalışmasına adamak için tüm maddi avantajlardan vazgeçmiştir. Albertus öldüğünde, ünü, arkadaşı Abbot Reginald'a 'Thesaurus Alchimae'sinde açıkça Albertus'un ve kendisinin dönüştürme sanatındaki başarılarından bahseden 'aziz öğrencisi' Aquinas'a geçti.

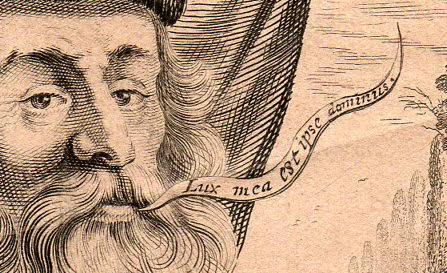

Raymond Lully, hayatı hakkında o kadar çok çelişkili kanıt bulunan simyacılardan biridir ki, adının aynı zamanda veya daha sonraki bir dönemde ikinci bir usta tarafından bir kapak olarak kullanıldığı pratik olarak kesindir. Muhtemelen 1235 dolaylarında Mayorka'da doğdu ve biraz ahlaksız bir gençlikten sonra, görünüşe göre başarısız bir aşk ilişkisinin trajik bir şekilde sona ermesiyle, düşüncelerini dine çevirmeye ikna edildi. Müjdeyi Muhammed'in takipçileri arasında yaymak için ateşli bir arzuyla doldu ve bu amaçla Müslüman öğretilerini daha iyi çürütmek için Müslüman yazılarını incelemeye yıllarını adadı. Yalnızca Avrupa'da değil, aynı zamanda dini coşkusunun birden fazla kez neredeyse hayatına mal olduğu Afrika ve Asya'da da çok seyahat etti. Arnold de Villanova ve Evrensel Bilim ile, simya üzerine yaptığı çalışma ve Felsefe Taşı'nın keşfi, eski ününü gayretli bir Hıristiyan olarak arttırdığı zaman, hayatının biraz ilerisinde tanıştığı söylenir.

Bir hikayeye göre, ünü otuz yıl simyada çalıştıktan sonra amacına, Felsefe Taşı'na ulaşmakta başarısız olan, zamanın Westminster Abbot'u John Cremer'e ulaştı. Cremer bu nedenle Lully'yi İtalya'da aradı ve güvenini kazanarak onu İngiltere'ye gelmeye ikna etti ve burada onu II. Edward ile tanıştırdı. Lully, Hıristiyan âleminin büyük bir savunucusu olarak, Edward'ın Haçlı Seferlerini parayla taşıması şartıyla, değersiz metalleri altına dönüştürmeyi kabul etti. Çalışması için Kule'de bir oda verildi ve 50.000 pound değerinde altını dönüştürdüğü tahmin ediliyor. Ancak bir süre sonra Edward açgözlü oldu ve Lully'yi dönüştürme işini sürdürmeye zorlamak onu esir etti, ancak Cremer'in yardımıyla Kule'den kaçıp Kıta'ya dönebildi. Kayıtlar, yüz elli yaşına kadar yaşadığını ve sonunda Asya'daki Sarazenler tarafından öldürüldüğünü belirtiyor. O yaşta genç bir adam gibi koşabildiği ve zıplayabildiği söylenir.

Lully'ye atfedilen yazıların muazzam çıktısı (dilbilgisi ve retorikten tıp ve teolojiye kadar çeşitli konularda toplam 486 risale vardır) ayrıca Lully adının sadece bir takma ad olduğunu düşündürür.

Simyacının metalleri dönüştürme iddiası, hemcinslerinin saflığını veya açgözlülüğünü sömürmek için yeterli inandırıcılığa ve vicdansızlığa sahip herhangi bir haydut için büyük olanaklar sunduğundan, bilimin ciddi bir itibar kaybına uğraması tam da bu sıralardaydı. Ne şarlatanlar ne de kurbanlar eksik değil. Zengin tüccarlar ve kazanç için açgözlü diğerleri, onları çoğaltmak umuduyla, kaybettikleri altın, gümüş ve değerli taşları sözde simyacılara emanet etmeye ikna edildi ve İngiltere'de Parlamento Yasaları kabul edildi ve Papa'nın Boğaları çıkarıldı. Papa John XXII'nin sanatı kendisinin icra ettiği ve bu yolla kamu hazinesini zenginleştirdiği söylense de, Hıristiyan âlemi ölüm acısı üzerine simya uygulamasını yasakladı.

On dördüncü yüzyılda, 'De Triplici Ordinari Exiliris et Lapidis Theoria' ve 'Mineralia Opera Sue de Lapide Philosophico' yazan baba ve oğul, Hollandalı ustalar olan iki Isaacs Hollandus yaşadı. Metaller üzerindeki işlemlerinin ayrıntıları, verilenlerin en açık olanlarıdır ve tam da bu netlik nedeniyle göz ardı edilmiştir. Örneğin, Kimya Profesörü John Read, 'Prelude to Chemistry, an Outline of Alchemy' adlı eserinde, Hollandus çiftinin yazısını birkaç kelimeyle reddeder, çünkü muhtemelen ayrıntıların netliği onun bir kör olduğundan şüphelenmesine neden olmuştur. Ne yazık ki, bazen uzmanların kendileri de kör olabiliyor..

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

... the heirs of St. Edward the Confessor were said to have a healing touch. And was she [Queen Anne] not i in the direct line of Kings? Some sovereigns had practiced the healing touch. Henry III was one. Edward I and II were others; and it was Edward III whose alchymist Raymond Lully actually made gold for him. On the coins he made were impressed the figures of angels and these coins were supposed too have a healing power and out they were bound on the arms of those who suffered from scrofula by royal hands the patients were said to be healed. Scrofula had become known as the King's Evil, and this practice which ensured the popularity of sovereigns, was known as touching for the King's Evil.

To have suffered brought to her that she might cure then was a blessing Anne could bestow on her subjects.

COURTING HER HIGHNESS by Jean Plaidy

A good short history lesson from Jean Plaidy (real name Eleanor Hibbert) there.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Germaine Tailleferre

1892-1983

Compositrice

France

Germaine Tailleferre est une compositrice de musique classique méconnue. Prolixe, intrépide dans ses choix créatifs, celle que Jean Cocteau surnommait affectueusement « Marie Laurencin pour l'oreille » a pourtant été en son temps une figure reconnue de la scène artistique française.

Germaine Tailleferre naît Germaine Taillefesse, dans une famille de petite bourgeoisie qui considère que le piano doit rester un loisir de jeune fille et non devenir une carrière. On retrouve cette brillante élève du Conservatoire de Paris au sein du « Groupe des six », un petit groupe d’étudiants particulièrement innovants qui se réunit régulièrement dans les cafés des villages d’artistes de Montmartre et Montparnasse à partir de 1917.

Entre deux cours de pianos dispensés pour financer ses études, Germaine Tailleferre vit alors de belles années d’émulation artistique. Elle se lie avec Modigliani ou Picasso, se dévoue à la composition avec Francis Poulenc, Georges Auric, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud et Louis Durey. Le Groupe des six innove par ses choix de mélodies et d’instruments. Leur nom s’inspire du « Groupe des cinq », des compositeurs russes qui valorisent les traditions et le folklore russes.

Après guerre, les Six se retrouvent souvent avec Marie Laurencin et Raymond Radiguet autour de Jean Cocteau. Leur réflexion poétique commune accouche en 1921 d’un ballet, les Mariés de la Tour Eiffel, somptueux et grinçant, pour lequel Tailleferre compose une valse et un quadrille.

Germaine Tailleferre est à l’origine d’une œuvre diversifiée. Elle jouit alors d’une importante reconnaissance pour sa musique enjouée, une musique « qui sent bon » selon Darius Milhaud. Elle compose Le marchand d’oiseaux en 1923, se lie avec Maurice Ravel qui lui donne de nombreux conseils et encourage son travail. Elle compose pour le piano et le violon, de la musique de chambre, pour orchestre, pour voix, des ballets pour les Saisons russes. Elle collabore avec Paul Valéry pour sa Cantate du narcisse et travaille avec Paul Claudel ou encore Igor Stravinsky.

La vie sentimentale de Germaine Tailleferre à l’inverse n’est pas si brillante. Elle épouse en 1925 un dessinateur humoristique américain pas vraiment drôle et s’installe avec lui aux États-Unis. Là, son mari se révèle à la fois possessif et jaloux de son succès et va jusqu’à l'empêcher de composer pour Charlie Chaplin. Ils rentrent à Paris et divorcent en 1929. Son second mari est à nouveau un soutien plus que tiède à sa carrière de compositrice. Elle passe les années de guerre aux États-Unis avec sa fille puis revient en France en 1946. Germaine Tailleferre divorce en 1955.

Elle compose de la musique de ballet pour l’Opéra-Comique mais c’est un échec critique. En revanche, Tailleferre reçoit à partir des années 1950 de nombreuses commandes pour la radio. Beaucoup de ses opéras et opérettes débutent leur carrière sur les ondes, et non sur une scène nationale. Elle compose pour l’ORTF en 1955 une Petite histoire lyrique de l’art français : du style galant au style méchant, soit cinq « opéras de poche » d’une vingtaine de minutes pastichant chacun les grandes époques de l’opéra, de Lully à Offenbach en passant par Rossini. Avec l’opéra La Petite sirène, elle expérimente la musique dodécaphonique. Son opéra Le Maître en 1959 est tiré d’un texte d’Eugène Ionesco.

Elle compose des musiques de films, part en tournée européenne avec le baryton Daniel Lefort. Elle compose Adieu au Cavalier, sur un poème d'Apollinaire, lorsqu’elle perd son ami Poulenc. Tailleferre connaît fréquemment des difficultés financières. Les dernières années, elle enseigne beaucoup afin de compléter une retraite très mince. Elle meurt en 1983, peu après avoir livré une dernière commande du Ministère de la Culture en 1981, le Concerto de la fidélité.

Faute d’avoir été soutenue par son proche entourage, Germaine Tailleferre doutait elle-même de la qualité de ses œuvres. Elle est l’oubliée du « groupe des Six » la plupart étant individuellement célébrés. Il est regrettable que son œuvre conséquente n’ait pas la visibilité qu’elle mérite.

Ses compositions, très enjouées, ont parfois été considérées avec dédain comme trop légères. Un dédain qui suscitait chez la compositrice un certaine amusement. Germaine Taillefer était sans doute trop modeste, mais néanmoins heureuse de son œuvre :

« Je n'ai pas grand-respect pour la tradition. Je fais de la musique parce que ça m'amuse, ce n'est pas de la grande musique je le sais. C'est de la musique gaie, légère, qui fait que, quelquefois, on me compare aux petits maîtres du XVIIIe siècle, ce dont je suis très fière ».

Photo : Portrait de Germaine Tailleferre - Studio Harcourt

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The stoning of Raymond Lully (Raymon Llull) -woodcut 1515

Flickr: https://flic.kr/p/D5Kifp

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

- Kayıtlara göre yüz elli yaşına kadar yaşamış ve sonunda Asya'da bedeviler tarafından öldürülmüştür. Onun yüz elli yaşında genç bir adam gibi koştuğu, hoplayıp zıpladığı söylenir.

Raymond Lully (1232-1315)

Simya Sanatı, Simyacılar, Syf.23

Archibald Cohen

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Raymond Lully, who was one of the great early alchemists, once pointed out that the alchemical transmutation was impossible unless the alchemist 'Himself' was in the process of transformation."

~Manly P. Hall

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Υπό την προστασία μιας συγκεκριμένης μορφής η ψυχή είναι ασφαλής.

Raymond Lully

1 note

·

View note

Text

Alchemy in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries

The first man to teach the chemistry of the human body and to declare that the true purpose of alchemy was the preparation of medicine for the treatment of disease was one Jean Baptista Van Helmont, a disciple of Paracelsus. Van Helmont has been called the “Descartes of Medicine” for his probing philosophical discourses. But he was also an accomplished alchemist. In his treatise, De Natura Vitae Eternae, he wrote: “I have seen and I have touched the Philosopher’s Stone more than once. The color of it was like saffron in powder but heavy and shining like pounded glass. I had once given me the fourth of a grain, and I made projection with this fourth part of a grain wrapped in paper upon eight ounces of quicksilver heated in a crucible. The result of the projection was eight ounces, lacking just eleven grains, of the most pure gold.”

In his early thirties, Van Helmont retired to an old castle in Belgium near Brussels and remained there, almost unknown to his neighbors until his death in his sixty-seventh year. He never professed to have actually prepared the Philosopher’s Stone, but he say he gained his knowledge from alchemists he contacted during his years of research.

Van Helmont also gives particulars of an Irish gentleman called Butler, a prisoner in the Castle of Vilvord in Flanders, who during his captivity performed strange cures by means of Hermetic medicine. The news of his cure of a Breton monk, a fellow-prisoner suffering from severe erysipelas, by the administration of almond milk in which he had merely dipped the Philosopher’s Stone brought Van Helmont, accompanied by several noblemen, rushing to the castle to investigate. In their presence Butler cured an aged woman of “megrim” by dipping the Stone into olive oil and then anointing her head. There was also an abbess who had suffered for eighteen years with paralyzed fingers and a swollen arm. These disabilities were removed by applying the Stone a few times to her tongue.

In Lives of the Alchemystical Philosophers (published in 1815), it is stated that prior to the events at Vilvord, Butler attracted some attention by his transmutations in London during the reign of King James I. Butler is said to have gained his knowledge in Arabia in a rather roundabout way. When a ship on which he had taken passage was captured by African pirates, he was taken prisoner and sold into slavery in Arabia. His Arab master was an alchemist with knowledge of the correct order of the processes. Butler assisted him in some of his operations, and when he later escaped from captivity, he carried off a large portion of a red powder, which was the alchemical Powder of Projection.

Dennis Zachare in his memoirs gives an interesting account of his pursuit of the Philosopher’s Stone during this period. At the age of twenty, he set out to Bordeaux to undertake a college curriculum, and hence to Toulouse for a-course of law. In this town, he made the acquaintance of some students in possession of a number of alchemical books. It seems that at this time there was a craze for alchemical experiments among the students of Paris and other French towns, and this craze caught Zachare’s imagination. His law studies were forsaken and his experiments in alchemy began. On his parents’ death, having expended all his money on his new love, he returned home and from their estate raised further money to continue his research. For ten years, according to his own statement, after experiments of all sorts and meetings with countless men with various methods to sell, he finally sat down himself to study carefully the writings of the philosophers on the subject. He states that it was Raymond Lully’s Testament, Codicil, and Epistle (addressed to King Robert) that gave him the key to the secret. From the study of this book and The Grand Rosary of Arnold de Villanova, he formulated a plan entirely different from any he had previously followed. After another fifteen months of toil, he says “I beheld with transport the evolution of the three successive colors that testify to the True Work. It came finally at Eastertide. I made a projection of my divine powder on quicksilver, and in less than an hour it was converted into fine gold. God knows how joyful I was, how I thanked Him for this great grace and favor and prayed for His Holy Spirit to pour yet more light upon me that I might use what I had already attained only to His praise and honor.” In his only writing (titled Opusculum Chemicum), Zachare gives his own personal narrative and states that the Great Art is the gift of God alone. The methods and possibilities of the transmutation of metals and the Elixir as a medicine are also considered.

There is also the evidence of John Frederick Helvetius, as he testified in 1666. He made claim to be an adept, but admitted he received the Powder of Transmutation from another alchemist. He wrote: “On December 27th, 1666, in the forenoon, there came a certain man to my house who was unto me a complete stranger, but of an honest, grave and authoritative mien, clothed in a simple garb like that of a Memnonite. He was of middle height, his face was long and slightly pock-marked, his hair was black and straight, his chin close-shaven, his age about forty-three or forty-four, and his native place North Holland, so far as I could make out. After we had exchanged salutations, he inquired whether he might have some conversation with me. It was his idea to speak of the ‘Pyrotechnic Art,’ since he had read one of my tracts, being that directed against the Sympathetic Powder of Sir Kenelm Digby, in which I implied a suspicion whether the Great Arcanum of the Sages was not after all a gigantic hoax. He took therefore this opportunity of asking if indeed I could not believe that such a Grand Mystery might exist in the nature of things, being that by which a physician could restore any patient whose vitals were not irreparably destroyed. My answer allowed that such a Medicine would be a most desirable acquisition for any doctor and that none might tell how many secrets there may be hidden in Nature, but that as for me — though I had read much on the truth of this Art — it had never been my fortune to meet with a master of alchemical science. I inquired further whether he was himself a medical man since he spoke.so learnedly about medicine, but he disclaimed my suggestion modestly, describing himself as a blacksmith, who had always taken great interest in the extraction of medicines from metals by means of fire.

“After some further talk the ‘craftsman Elias’ — for so he called himself — addressed me thus: ‘Seeing that you have read so much in the writings of the alchemists concerning the Stone, its substance, color, and its wonderful effects, may I be allowed to question whether you have yourself prepared it?’

Coin minted from alchemical gold showing the symbol for lead raised to the heavens.

“On my answering him in the negative, he took from his bag an ivory box of cunning workmanship in which there were three large pieces of a substance resembling glass or pale sulfur and informed me that here was enough of his tincture there to produce twenty tons of gold. When I held the treasure in my hands for some fifteen minutes listening to his accounting of its curative properties, I was compelled to return it (not without a certain degree of reluctance). After thanking him for his kindness, I asked why it was that his tincture did not display that ruby color that I had been taught to regard as characteristic of the Philosophers’ Stone. He replied that the color made no difference and that the substance was sufficiently mature for all practical purposes. He brusquely refused my request for a piece of the substance, were it no larger than a coriander seed, adding in a milder tone that he could not do so for all the wealth which I possessed; not indeed on amount of its preciousness but for another reason that it was not lawful to divulge, Indeed, if fire could be destroyed by fire, he would cast it rather into the flames.

“Then, after some consideration, he asked whether I could not show him into a room at the back of the house, where we should be less liable to observation. Having led him into the parlor, he requested me to produce a gold coin, and while I was finding it he took from his breast pocket a green silk handkerchief wrapped about five gold medals, the metal of which was infinitely superior to that of my own money. Being filled with admiration, I asked my visitor how he had attained this most wonderful knowledge in the world, to which he replied that it was a gift bestowed upon him freely by a friend who had stayed a few days at his house, and who had taught him also how to change common flints and crystals into stones more precious than rubies and sapphires. ‘He made known to me further,” said the craftsman, ‘the preparation of crocus of iron, an infallible cure for dysentery and of a metallic liquor, which was an efficacious remedy for dropsy, and of other medicines.’ To this, however, I paid no great heed as I was impatient to hear about the Great Secret. The craftsman said further that his master caused him to bring a glass full of warm water to which he added a little white powder and then an ounce of silver, which melted like ice therein. ‘Of this he emptied one half and gave the rest to me,’ the craftsman related. ‘Its taste resembled that of fresh milk, and the effect was most exhilarating.’

“I asked my visitor whether the potion was a preparation of the Philosophers’ Stone, but he replied that I must not be so curious. He added presently that at the bidding of his master, he took down a piece of lead water-pipe and melted it in a pot. Then the master removed some sulfurous powder on the point of a knife from a little box, cast it into the molten lead, and after exposing the compound for a short time to a fierce fire, he poured forth a great mass of liquid gold upon the brick floor of the kitchen. The master told me to take one-sixteenth of this gold as a keepsake for myself and distribute the rest among the poor (which I did by handing over a large sum in trust for the Church of Sparrendaur). Before bidding me farewell, my friend taught me this Divine Art.’

“When my strange visitor concluded his narrative, I pleaded with him to prove his story by performing a transmutation in my presence. He answered that he could not do so on that occasion but that he would return in three weeks, and, if then at liberty, would do so. He returned punctually on the promised day and invited me to take a walk, in the course of which we spoke profoundly on the secrets of Nature he had found in fire, though I noticed that my companion was exceedingly reserved on the subject of the Great Secret. When I prayed him toentrust me with a morsel of his precious Stone, were it no larger than a grape seed, he handed it over like a princely donation. When I expressed a doubt whether it would be sufficient to tinge more than four grains of lead, he eagerly demanded it back. I complied, hoping that he would exchange it for a larger fragment, instead of which he divided it with histhumbnail, threw half in the fire and returned the rest, saying ‘It is yet sufficient for you.”

The narrative goes on to state that on the next day Helvetius prepared six drachms of lead, melted it in a crucible, and cast in the tincture. There was a hissing sound and a slight effervescence, and after fifteen minutes, Helvetius found that the lead had been transformed into the finest gold, which on cooling, glittered and shone as gold indeed. A goldsmith to whom he took this declared it to be the purest gold that he had ever seen and offered to buy it at fifty florins per ounce. Amongst others, the Controller of the Mint came to examine the gold and asked that a small part might be placed at his disposal for examination. Being put through the tests with aqua fortis and antimony it was pronounced pure gold of the finest quality. Helvetius adds in a later part of his writing that there was left in his heart by the craftsman a deeply seated conviction that “through metals and out of metals, themselves purified by highly refined and spiritualized metals, there may be prepared the Living Gold and Quicksilver of the Sages, which bring both metals and human bodies to perfection.”

In Helvetius’ writing there is also the testimony of another person by the name of Kuffle and of his conversion to a belief in alchemy that was the result of an experiment that he had been able to perform himself. However, there is no indication of the source from which he obtained his powder of projection. Secondly, there is an account of a silversmith named “Grit,” who in the year 1664, at the city of the Hague, converted a pound of lead partly into gold and partly into silver, using a tincture he received from a man named John Caspar Knoettner. This projection was made in the presence of many witnesses and Helvetius himself examined the precious metals obtained from the operation.

In 1710, Sigmund Richter published his Perfect and True Preparation of the Philosophical Stoneunder the auspices of the Rosicrucians. Another representative of the Rosy Cross was the mysterious Lascaris, a descendant of the royal house of Lascaris, an old Byzantine family who spread the knowledge of the Hermetic art in Germany during the eighteenth century. Lascaris affirmed that when unbelievers beheld the amazing virtues of the Stone, they would no longer be able to regard alchemy as a delusive art. He appears to have performed transmutations in different parts of Germany but then disappeared and was never heard from again.

30 notes

·

View notes