#roxana zal

Photo

Testament (Lynne Littman, 1983).

#lynne littman#testament#testament (1983)#jane alexander#roxana zal#carol amen#john sacret young#steven poster#suzanne pettit#david nichols#linda pearl#waldemar kalinowski#julie weiss

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

r i v e r' s e d g e, 1986 🎬 dir. tim hunter

#film#drama#crime#river's edge#River's Edge 1986#tim hunter#crispin glover#keanu reeves#Ione Skye Leitch#daniel roebuck#dennis hopper#joshua john miller#Roxana Zal#Josh Richman

137 notes

·

View notes

Photo

River's Edge (Tim Hunter, 1986)

Cast: Crispin Glover, Keanu Reeves, Ione Skye, Daniel Roebuck, Dennis Hopper, Joshua John Miller, Roxana Zal, Josh Richman, Phillip Brock, Tom Bower, Constance Forsland, Leo Rossi, Jim Metzler. Screenplay: Neal Jimenez. Cinematography: Frederick Elmes. Production design: John Muto. Film editing: Howard E. Smith, Sonya Sones. Music: Jürgen Knieper.

I'm a faithful watcher of credits, even though today they're sometimes as long as the movie itself. I think if those people devoted their time to making the movie, they deserve a little of my time watching their names scroll by. Oh, okay, not really. The actual reason for watching the credits is that sometimes they reveal tidbits of fascinating information, such as this one for River's Edge: "trainer: Mr. Glover." I have to wonder what Crispin Glover's trainer did: It's not a particularly challenging role physically, so I have to assume it had something to do with keeping the actor from going further over the top than he does in his mannered and eccentric performance as Layne, an adolescent pothead who gets caught up in the aftermath of the murder of a teenage girl. River's Edge was something of a shocker in its day, variously interpreted as an indictment of American society's failure to provide a clear direction for bored and alienated youth, or as a critique of parenting or the school system, or just as a horror story masked as a true crime movie. The screenplay by Neal Jimenez has its roots in two news stories about teenagers in different parts of California who knew about the murder of one of their schoolmates but covered it up. It's not just the teens who get their share of blame: The adults include negligent parents, a half-crazed loner, an ineffective teacher, bullying cops, and the usual gaggle of reporters. That the half-crazed loner is played by Dennis Hopper links River's Edge with another and more celebrated movie of 1986: David Lynch's Blue Velvet. There are moments in Tim Hunter's film, especially when Hopper's character is clinging to his beloved inflatable sex doll, that rival Lynch's. Lynch, however, would probably not have been so tender as Jimenez and Hunter are to the lovers played by Keanu Reeves and Ione Skye, who lend a romantic John Hughes note to the film that dulls its edge.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

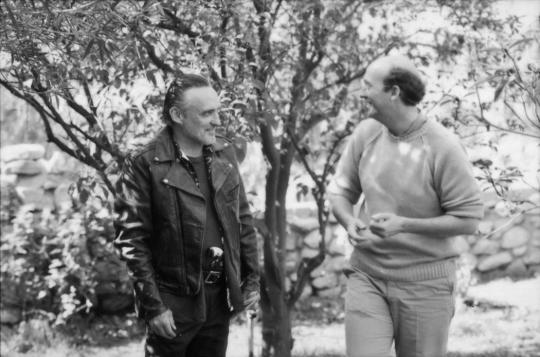

Keanu Reeves, Crispin Glover, and Roxana Zal on set of River's Edge, 1986

138 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

5 minutes of dialogue from The Stranger. None of the plot is spoiled.

Summary -

Robert Cuccioli: *ominous dialogue*

#the stranger (1999)#roxana zal#robert cuccioli#want to understand LESS about this movie? watch this

13 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

RIVER’S EDGE (1986)

Grade: C-

You could see what they wanted to do here, it might have worked in '86, but a lot will change in this script if made now.

#River's Edge#1986#C#Crime Films#High School#Tim Hunter#Drama Films#Murder#Crispin Glover#Keanu Reeves#Ione Skye#Daniel Roebuck#Dennis Hopper#Joshua John Miller#Roxana Zal#Phillip Brock#Tom Bower#Constance Forslund#Leo Rossi#Jim Metzler#Danyi Deats#Friends

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

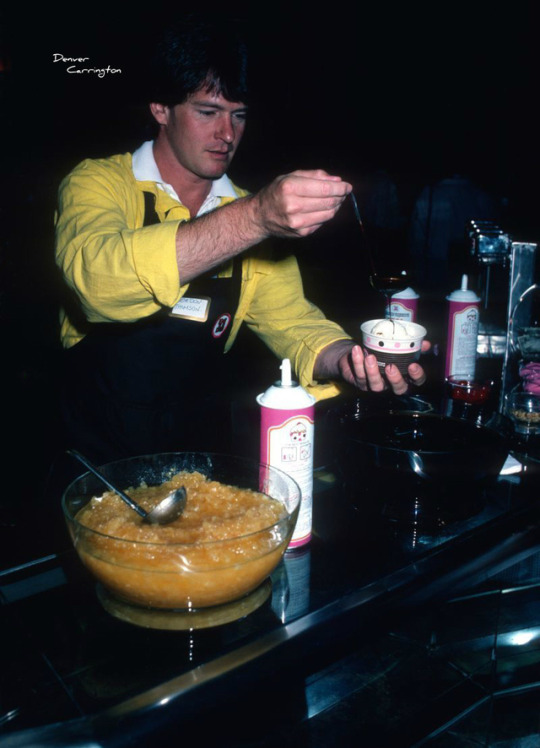

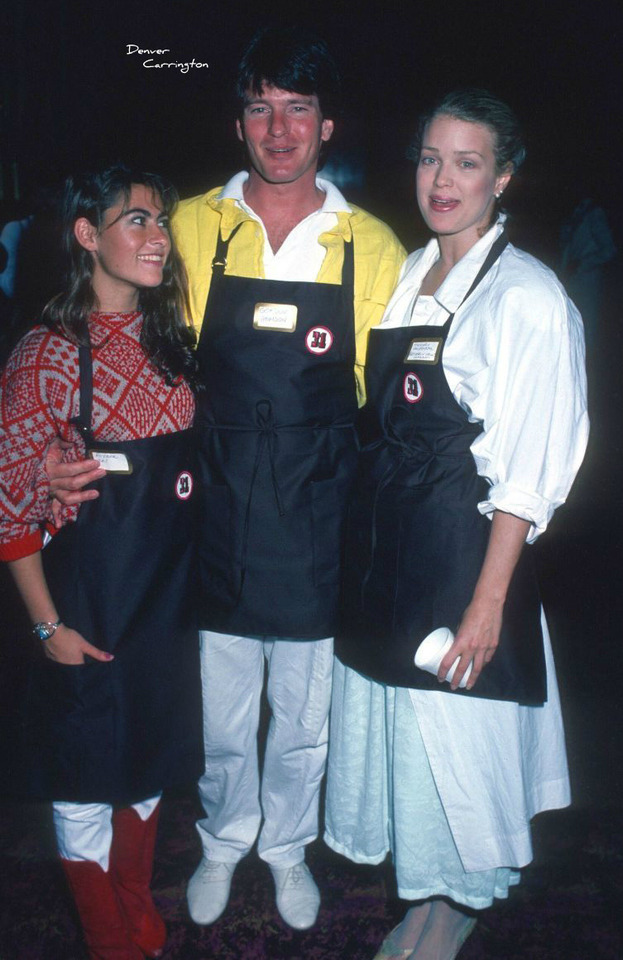

Gordon Thomson (Adam) in what looks like some kind of charity event involving Baskin-Robbins. In the second picture, he’s with Roxana Zal and Melody Anderson.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

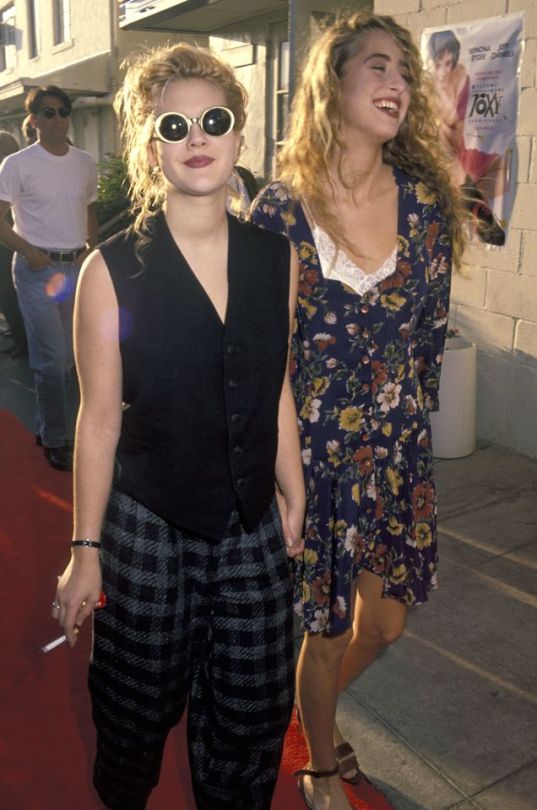

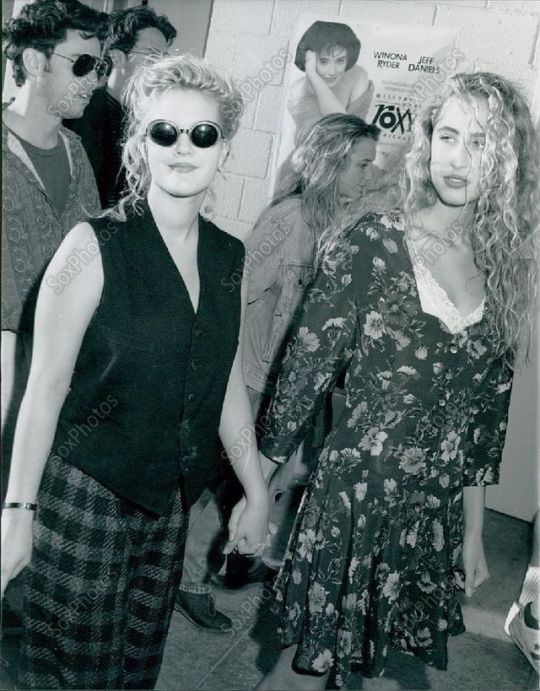

Actresses Shannen Doherty (aged 19) and Drew Barrymore (aged 15) attend the “Welcome Home, Roxy Carmichael” Hollywood Premiere on September 30, 1990 at Paramount Studios in Hollywood, California. (Drew with Roxana Zal in one picture). Everytime I see these pics I wonder… Both actresses grew in the spotlight. Drew had troubles and luckily by 1990 she was recovered. Shannen’s nightmare just would start two years later. I guess the press (tabloids) always want their broken girl or child. They are just young and strong girls and women that want to live from their dream, from what they love doing. But are strong and opinion-minded, and many people dislike that. Every now and then we have the “troubled” young woman who struggles with some kind of problems (like Lindsay Lohan, or Miley Cyrus more recently). I find sad what these scene do to them. It’s like they enjoy to see young “fallen” women. It is not fair. They are just being themselves in a world that it seems if you are not part of that they believe is right, then you are the “bad girl”.

#shannen doherty#drew Barrymore#1990#1990s#welcome home Roxy Carmichael#1990 events#1990s events#Hollywood#bad girl#troubled star#actress#actresses#me too#time's up#lindsay lohan#Miley Cyrus#woman#girl#child

42 notes

·

View notes

Link

History could be made at this year’s Emmys if 13-year-old Noah Schnapp earns a nomination as Best Drama Supporting Actor for Netflix’s “Stranger Things.” Schnapp, who wasn’t even alive in the 1980s when the sci-fi series takes place, would tie as the youngest male actor ever to be nominated for a drama series. Back in 1959 another 13-year-old, Johnny Crawford (“The Rifleman”), earned a nomination but lost. Two female starlets have taken home Emmy Awards — Roxana Zal for “Something About Amelia” (age 14 in 1984) and Kristy McNichol for “Family” (age 15 in 1977, age 17 in 1979) — but Schnapp would make history for the boys if he were to win for his breakout role in “Stranger Things.”

Read more here.

#strangerthingsedit#strangerthingsedits#dailystrangerthings#strangerthingsdaily#strangerthingssource#stranger things#noah schnapp#cast: noah#news: noah#strangerthingscast#stranger things cast

531 notes

·

View notes

Text

Keanu Reeves, Crispin Glover, Roxana Zal, Josh Richman, Daniel Roebuck, lone Skye and Phillip Brock on the set of RIVER'S EDGE (1986)

#rivers edge#1980s cinema#1980s movies#set pics#keanu reeves#ione skye#movie photography#1980s photography

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Keanu Reeves, Crispin Glover, Roxana Zal, Josh Richman, Daniel Roebuck and Ione Skye. (Photo by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer/Getty Images)

An Oral History of 'River's Edge,' 1987's Most Polarizing Teen Film

MG

Matt Gilligan

May 9 2017, 6:00pm

From Keanu's first big role to Crispin Glover's weirdest wigs, a look back at the making of the indie thriller.

The 1987 film River's Edge was a film that shocked audiences and critics alike with its depiction of aimless teenagers in a dead-end town. Roger Ebert called the film "an exercise in despair" and "the best analytical film about a crime since The Onion Field and In Cold Blood." "Bleak" is the word that sums up Tim Hunter's groundbreaking film.

River's Edge is a fictionalized account of a 1981 murder case in Milpitas, California, in which 16-year-old Anthony Jacques Broussard strangled 14-year-old Marcy Conrad and dumped her body near the foothills outside of town. For two days, Conrad's murder went unreported, as Broussard brought classmates from Milpitas High School to view Conrad's dead body. The story received widespread media attention as parents grappled with tough questions: Were America's children completely amoral? What did they believe in? Did they believe in anything?

Working from a script by Neal Jimenez, Hunter's film offered a dark, intense portrait of troubled teenagers. The kids in River's Edge stood in direct contrast to the shiny, plastic teenagers that movie audiences were accustomed to seeing in the mid-to-late 1980s. These young people were the anti-Brat Pack: They drank, smoked weed, popped pills, and seemingly had no moral compass and no role models.

The film's characters also looked different than the polished mallrats of other 80s films; they perfected the "grunge" look years before the American mainstream had even heard of the term. The film's soundtrack also strayed from most contemporary films, featuring metal and punk bands such as Slayer, Hallow's Eve, Agent Orange, and the Wipers—the perfect soundtrack for a story about alienated young people with no hope and no direction. The cast featured a combination of young, dynamic actors, and one legendary Hollywood hellraiser in the midst of a monumental comeback after a public downfall with booze and drugs.

To commemorate the 30th anniversary of River's Edge, I spoke with six people involved in making the film to get their thoughts, stories, and opinions about its backstory and legacy.

BEFORE River's Edge

Daniel Roebuck (Actor): My career before River's Edge was the black void of space—not unlike what was here before the Big Bang. I got the lead role in a movie called Cavegirl, and that [was it].

Tim Hunter (Director): My father was a screen and TV writer, so I was a movie brat. I always knew I wanted to [make movies] from an early age. I made a bunch of woeful student films, and I was included in the first class at the American Film Institute in 1970.

Ione Skye (Actor): I grew up in LA and my brother [Donovan Leitch] was auditioning for things, but I didn't want to be an actor. I had modeled for friends, and that was the extent of my involvement in the industry because I was in high school.

Midge Sanford (Producer): My partner Sarah Pillsbury won an Academy Award for a short film she produced but she couldn't get a job in the business. She decided to start a production company. We met, and she told me about her company. I felt ready to jump into it. Sarah was able to raise $450,000 to get us started, so we had money to option scripts and books. if we didn't have that development fund, it would've been difficult for anybody to pay attention to us. Having a little bit of money helped us option material that we really liked.

THE SCRIPT

Neal Jimenez (Screenwriter): There was a news story about a kid who dumped a body and took his friends to see it. I was in a screenplay class at UCLA, and I wrote it for the class. Most of the characters were based on people I had gone to high school with. I thought it spoke to a mood that young people were feeling at the time—feeling detached from things and wanting to zone out. I entered a screenplay contest that was judged by fellow students. One of them was doing an internship with a production company that [producer] Amy Pascal was involved with. He gave it to her and she gave it to the person who became my agent, who gave it to Midge and Sarah.

Sanford: We thought the script was really good. If somebody had pitched us this idea in our office or at a lunch, I don't think either one of us would have responded so positively to it because it was so dark. But it was already written, so we could see it on the page and imagine it as a movie. We were fans of Tim's, so we sent him the script.

Hunter: I was dubious. I didn't want to do another teen picture. But the script was so incredibly good. I called them back instantly and told them I had to do it.

Sanford: Tim said, "My agent's gonna kill me, but I want to do it."

Hunter: There was another director in the running, and I really lobbied hard for it. Midge and Sarah had been showing the script to studios in the $5 million range—nobody would touch it because it was so dark.

Sanford: I remember somebody saying, "I read the script and I think it's really good, but it's very disturbing and I couldn't get it out of my mind." My thought was, that's why you make a movie.

Hunter: As part of my lobbying campaign, I said I'd make it for a million dollars. All of the sudden, it was possible to submit it to a number of young indie companies that were popping up at the time.

Sanford: Hemdale were a small company that made some very good movies, like Salvador and Hoosiers. They really responded to the script and said they would finance it with Tim as the director.

Hunter: It was in pre-production four months later. We were trying to make it as inexpensively as possible. The final budget, I think, was $1.7 million.

Carrie Frazier (Casting Director): They had to hire someone like me who needed the job but wasn't looking for a big paycheck. The first time I read the script, I loved it. I thought it was powerful and weirdly funny, and it had a darkness that was rooted in reality in a way that I hadn't seen before.

Director Tim Hunter with cast and crew on the banks of the American River in Sacramento (credit Daniel Roebuck)

ASSEMBLING THE TEAM

Hunter: We set up shop in an old film production building on Victory Boulevard in the Valley. We didn't have money to offer it to any of John Hughes' Brat Pack crowd, so we auditioned dozens of young actors.

Skye: Every teenager in town who was acting was excited about [auditioning]. My mom's friend took a picture of me for LA Weekly, and the casting director saw it. My brother came home from school and said, "You want to audition for this movie? The casting director asked about you." I read the scenes they had us audition for, and I was like, "Wow, this is good." I thought it was dark—I admired it. I never did well in school—I was in Hollywood High, I was ditching classes. I didn't want to go [audition] because I was terrified, but I pushed myself to audition and I got it.

Roebuck: I put on a costume, and KY jelly in my hair to make it look greasy. On the way to the audition, I stopped by a 7-11 by my house in Hollywood, bought two beers, and put them in my coat pocket. When I walked into the room, I sat in the corner and popped open the beer, and Tim grabbed his camera and started shooting. I think he was seeing something in that moment that was unique, different, and real.

Frazier: When [Keanu Reeves] came in, he hadn't done anything and wasn't being represented by anybody. He was what's called a hip-pocket client, meaning they didn't know if they wanted to sign him—they were just testing him out. He walked in the door, and I went, "Oh my god, this is my guy!" It was just because of the way he held his body—his shoes were untied, and what he was wearing looked like a young person growing into being a man. I was over the moon about him.

Sanford: For Dennis Hopper's role ['Feck'], we sent the script to Harry Dean Stanton, who passed. Apparently, Harry Dean Stanton passed on a lot of scripts and gave them to Dennis.

Hunter: I initially hoped that John Lithgow would play it, but it was too dark for John—he wanted no part of it. We had some reluctance that it might be typecasting for Dennis, but ultimately we wanted him very badly and we needed Hemdale to come up with a little extra money for him. I threatened to cast Timothy Carey, who was in Stanley Kubrick's The Killing and John Cassavetes's The Killing of a Chinese Bookie. He was brilliant, but also a well-known wild man who never stuck to a script—he'd ad lib and be quite disruptive. The thought of having Timothy Carey in the picture finally convinced Hemdale to come up with that small amount of money to pay Dennis to do it.

Roebuck: When they said it was Dennis Hopper, I almost shit myself.

Sanford: I think Crispin Glover came in [to audition] with a wig and an outrageous take on the part. He was so out there that Sarah and I were a little nervous about what he was doing. But we trusted him and felt like it would work out in the end.

Frazier: There was one part that was surprisingly tricky to cast: the dead body, Jamie. [We were like,] "Oh shit, who's gonna play that part?" I started to meet people who were young and could be comfortable naked. We had this wonderful young actress come in, Danyi Deats. She had to lie there cold and naked for days and really look dead, with all this makeup all over her. She's an unsung hero.

Corey Haim on set as "Tim" before he was replaced by Joshua Miller because of an illness (Credit: Jane O'Neal)

Corey Haim on set as "Tim" before he was replaced by Joshua Miller because of an illness (Credit: Jane O'Neal)

THE PRODUCTION

Hunter: We originally cast Corey Haim, but he got sick after the first day of production—pneumonia or something—and we had to let him go.

Hunter: The big challenge was nature. Neal Jimenez grew up in Sacramento, so we went there to shoot on the American River. There was a huge storm and flood when we started shooting, so the company that was bonding the picture didn't want us anywhere near Sacramento.

Sanford: We tried to find a river in LA. The LA River was pretty dry. There were creeks in Malibu—nothing that looked like a river.

Hunter: At the very last minute, before we were scheduled to go up to Sacramento, the waters ebbed and everybody made it up there. Coming off the heels of the storm and flood, the water had that wild, raging, marvelous quality that it didn't have before.

Hunter: I settled on Tujunga for the major locations—a community up in the foothills above Burbank that was originally settled in the first part of the century. It was an area where people with tuberculosis could come to sanatoriums for the clean air. By the time we shot River's Edge, it had become a smog pocket—but it was full of river rock houses that gave it a "land that time forgot" feeling.

Josh Richman, director Tim Hunter, Daniel Roebuck, and Crispin Glover on set (Credit: Jane O'Neal)

THE CAST

Sanford: We were doing a table read and Dennis Hopper walks in wearing a suit and carrying a briefcase. It was such a funny image, because you think of Dennis Hopper as this kind of outlaw. When we were making the movie, the only thing that he hadn't quit was smoking, and he was trying to stop.

Hunter: Hopper was wonderful. He'd just cleaned up his act and was very proud of it. He made himself available to all of those kids—who idolized him—and he rehearsed with them extensively. It was a really good experience.

Roebuck: We'd be sitting in a school gymnasium where we were having dinner late, and [the Apocalypse Now documentary] Hearts of Darkness hadn't come out yet, so he'd enlighten me with great stories about that. He'd take his shots at me, too. I'd miss a mark and he'd say, "A better actor could hit his mark," and he'd miss his mark and I'd say, "A younger actor could hit his mark." We laughed a lot. Anything Dennis Hopper said was about 10,000 times more interesting than anything I could have ever conceived of. He'd lived such an extraordinary life.

Skye: We were all fascinated with Crispin Glover. I was so impressed with his boldness, because I was very interested in not being a fool. Over the years, I've loosened up, and I was very influenced by Crispin. He's just one of those great actors who seemed very real but also could be just completely out there. I'll be honest with you, I love Crispin Glover. I think he is one of the most unique and interesting people I've ever met in my life.

RECEPTION

Roebuck: I had this private screening at a screening room on Sunset Boulevard one night. I invited my closest friends to see it. I met this guy Duane Whitaker when we were extras on General Hospital—he went on to be in Pulp Fiction—and he was the only one who said, "This is a great movie, and they're gonna be talking about it in 30 years." And he was 100% right.

Skye: The first time I saw it was a small screening, and it was very surreal—like I was on acid or something. I saw it later with a bigger screening with the whole cast. We saw a lot of dark humor in it, and had a good time. The audience didn't know how to take it—they were just shocked by the whole thing.

Jimenez: I remember being surprised by Crispin Glover's performance, which took me a while to warm up to. But as years went by, I really grew to like it.

Sanford: Some executives from a small distribution company wouldn't look at us [after a festival screening]. People either embraced it or were very put off by it. It didn't get picked up right away.

Hunter: I went to every goddamn festival screening I could. The reactions were good, but it didn't really take off until Sundance.

Sanford: The head of marketing at Island Pictures, Russell Schwartz, loved the movie and said, "I don't know how I'm gonna sell this movie, but I'm gonna figure it out." He was relentless.

Hunter: The screening I remember most before the film opened was in San Jose, near Milpitas, where the actual murder had taken place. A lot of the audience was up in arms, saying, "Why are you raking us over the coals again? Why are you bringing this all back? We've had enough notoriety with this murder case." But the principal of the local high school and people from the police department came up to us afterward and said that we'd really gotten it right—that's what those kids were like.

Dennis Hopper with director Tim Hunter (Credit: Jane O'Neal)

LEGACY

Sanford: It's held up. Teenagers take themselves very seriously, and this movie was a morality play. What would you do? And it's not just about kids. What if you found out your husband had killed somebody? What's your moral stance? People are still murdered, and people still don't tell. Kids can still feel alienated from society, too. If having a legacy means will it continue to have meaning to people years later, then it feels to me like it will.

Roebuck: It was so evocative of that moment in time. There were other movies about teenage angst, but because [River's Edge] was based on something real, it immediately shocked people.

Skye: It had a certain quality to it that was above and beyond certain indies. It was the beginning of my career, too. I thought it would be a one-off thing—"I was once in a movie"— but when I was approached by agents at a screening, I thought, "I can do this."

Frazier: I saw the movie recently and I was impressed by how well it held up. It's a cautionary tale. I don't think it's far away from where a lot of kids function these days.

Hunter: The fact that the film is still shown and that people still come up to me and say that it meant something to them means a lot to me. My legacy is that I made one film that made a difference to some people. It's not necessarily an auteur's career, but I'm not so unhappy about it, either. After River's Edge, I turned a lot of stuff down that I probably shouldn't have turned down. The features that I made weren't successful, and I went largely into television, as many directors do. The main thing for me is that I just love directing, so I've enjoyed [working in television] more than I would've if I'd had to wait four years between features. For me, the legacy of River's Edge is that I got to make it. I had such admiration for Neal's script that I remember thinking, "Please God, just one more in my career as good as this one." It hasn't happened yet, but gee, it was a good script.

(x)

_____

Thanks to Ayako Ueda for finding and sharing !

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

River’s Edge **** (1986, Crispin Glover, Keanu Reeves, Ione Skye, Roxana Zal, Daniel Roebuck, Dennis Hopper) - Classic Movie Review 5132

River’s Edge **** (1986, Crispin Glover, Keanu Reeves, Ione Skye, Roxana Zal, Daniel Roebuck, Dennis Hopper) – Classic Movie Review 5132

Director Tim Hunter’s notable 1986 cult success boasts outstanding, memorable eccentric acting turns from Dennis Hopper as a crippled drugs supplier and Crispin Glover as a crazy customer.

Neal Jimenez is the writer of this bleak and upsetting tale of dislocated California teenagers who find out that their unrepentant, high school slacker buddy Samson (Daniel Roebuck) has killed his girlfriend,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

The Virtue of Stillness: The Performances of Glenn Close

Midway through “The Wife,” Nathaniel (Christian Slater) asks Joan (Glenn Close) about her writing. The wife of Joe (Jonathan Pryce), the new winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, Joan gave up her own burgeoning career decades ago. She gives a slight smile in amused contempt. “I’m not a writer. I had some potential.” Bone burrows further, trying to find the reasons why, the feelings she has about living largely in his shadow, and a greater truth about her creative influence over him. The mask doesn’t slip: beyond a mocking laugh (“Aren’t you the therapist?”), she reveals very little. Her face and body hardly move. When they do, she’s mostly toying with him. No matter how much he prods and probes, she’s in total control, ready to take whatever secrets she has to her grave.

“The Wife” features one of Close’s best performances, and her most notable role in some time. Once one of the top actresses in Hollywood, garnering five Oscar nominations in a seven-year span, she’s had more success on TV as of late, earning two career-high roles on major FX dramas while mostly popping up on film to bring a certain level of professionalism to small roles. Seeing her in action again in “The Wife” is seeing a performer who gets more out of stillness than almost any other actor, using small glances and smirks to reassure or unnerve, depending on the moment. No matter the character’s intentions, however, she’s almost always the figure whose choices shape the lives of the people around her, for good or for ill.

Close came to acting after an unusual youth: born in an affluent world, her family forsook their privilege to join the Moral Re-Armament, a communal group that Close has since described as a cult that “[dictated] how you’re supposed to live and what you’re supposed to say and how you’re supposed to feel.” After exiting the MRA at 22 (her family has also since left), she studied theater and anthropology in college before beginning her professional career on Broadway at 27, acting in shows ranging from “King Lear” to “Barnum,” for which she earned a Tony nomination. It was on stage that George Roy Hill saw her and chose to cast her in her first film, “The World According to Garp.”

On paper, the choice to cast Close as the mother of Robin Williams despite their four-year age gap is curious. In practice, it’s perfect. Even beyond her relatively late start on film at 35, Close shows the sensibility of an older, wiser, and slightly stranger woman. As Jenny Fields, she walks through life with a unique combination of maternal warmth and steely determination. It’s funny when she answers her son Garp’s big, philosophical questions with an unearthly matter-of-factness (“Everybody dies … the thing is to have a life before we die”), and funnier still when she races into situations on a whim without any measure of self-consciousness. In a scene in which Jenny and Garp get a cup of coffee with a prostitute, Close’s uninhibited curiosity manifests itself in an exaggerated forward lean and unbroken gaze, as if the whole idea of sex for pleasure (something she doesn’t partake in or seem to understand) were both inexplicable and fascinating rather than commonplace. Better still is her utter bewilderment and matter-of-fact dismissal of the idea that prostitution is illegal (“that’s silly!”). Close’s Jenny radiates intelligence, confidence, righteousness and sweetness in a way that makes it easy to see why a whole movement might form around her as a feminist icon, as it does. At the same time, her nurturing but domineering nature, however well-meaning, warp Garp in ways she couldn’t possibly have predicted, showing how children can mirror their parents while reacting wildly against them.

“Garp” earned Close her first of six unsuccessful Oscar nominations (she has more without a win than any living performer). She garnered two more in consecutive years, first in Lawrence Kasdan’s “The Big Chill,” then in Barry Levinson’s adaptation of “The Natural.” Both big middlebrow hits at the time, neither film has aged particularly well, the former playing to Boomer narcissism while only somewhat undermining it, the latter selling out the downbeat ending to Bernard Malamud’s novel for triumphant but hollow iconography. Still, Close makes an impression in her limited role in both films. As Sarah Cooper in “The Big Chill” (pictured above), she puts on a good face as the mother figure in the group of friends, hiding her deep self-judgment for her affair with their dead friend, Alex. In a confession to JoBeth Williams’ Karen, she races through her story without putting too fine a point on any of the words, letting their rueful tone come through naturally, suggesting grief and nostalgia in equal measures. Iris Gaines in “The Natural” is less interesting, too strenuously symbolic of down-home absolute goodness, but Close lends the character some tenderness with a regretful, almost whispering tenor that helps chip away at how tediously forgiving the character is on paper.

A more interesting role, improbably, came with the 1984 Randa Haines-directed ABC movie-of-the-week “Something About Amelia.” Close plays Gail, the mother to a teenager (Roxana Zal) who tells her guidance counselor that her father (Ted Danson) has sexually abused her. The film’s strongest thread is Close’s gradual journey from furious disbelief to agony: Close beautifully underplays her initial reaction, her smile slackening but not quite fading as she prods insistently, taking a soft, defeated tone as she refuses to accept it. When she later realizes the truth, Close’s gestures are just as inspired: first crooking her head slightly (“you’re not lying, are you?”) then, after a furious outburst (“why did you let him?”), she races toward her daughter almost as if she might strike her before embracing her, that pent up energy and anger falling away in an instant. The film is smarter and more sensitive than one might expect, but Close’s choices cut the deepest as she gradually internalizes Gail’s deep guilt, letting it guide how she makes decisions for her family.

Guilt and disbelief come into play in 1985’s crackerjack thriller “Jagged Edge” as well. Close plays Teddy Barnes, a top lawyer who reluctantly takes the case of a rich man (Jeff Bridges, chillingly unreadable) accused of murdering his wife, going against the sleazy district attorney/her former boss (Peter Coyote). Close plays Teddy’s growing attraction to Bridges deftly, leaning in but demurring before she’s under his spell. She’s even better in the courtroom or when butting heads with rivals and her skeptical P.I. friend (Robert Loggia, equal parts vulgar and decent), radiating justifiable confidence without being smug, bringing the same matter-of-fact tone she brought to Jenny Fields (“If he didn’t do it, I’ll get him off … if he didn’t do it, I’ll get him off”) for another unfailingly determined heroine. But more revealing is how she plays Teddy’s remorse for her role in an innocent man’s conviction and suicide, her usual composure only barely holding as her voice and breathing almost fail when she finally admits fault. It’s in these moments that Close shows a powerful but decent woman showing the whys of her change in worldview, as well as the hows of her manipulation by malevolent men.

Close spent the first few years of her film career playing largely well-meaning maternal figures, with her first attempt at a change of pace falling flat with Paul Aaron's “Maxie,” in which Close’s spirited attempt to play a mousy woman possessed by the ghost of a flapper girl are defeated by lackadaisical direction and writing. She got a better opportunity two years later in Adrian Lyne’s 1987 erotic thriller “Fatal Attraction” (pictured above), her most iconic role. Alex Forrest initially comes across much like Teddy: self-assured, inviting, even glamorous. She beams at Michael Douglas’ Dan and picks the exact moments at which to look at him, averting her eyes when broaching the subject of their mutual attraction, then staring straight into his eyes, unblinking: “We’re two adults.”

It’s easy to read Close’s energy early in the film as mere persistence before her actions become more troubling, first with an attempted suicide attempt after a rejection, then with unending calls and unwanted office visits. Close, an advocate for mental health issues (her sister has bipolar disorder), has since expressed misgivings about how the film eventually turns Alex into a knife-wielding psychopath for a conventional thriller ending (one she fought at the time, when it was decided that the film’s original conclusion was too bleak). James Dearden’s script takes too many shortcuts with Alex’s psychology, but Close more than compensates, playing her as troubled, not crazy. She manages to find intonations that suggest she’s behaving the only rational way, given Dan’s callousness (“I’m not going to be ig-NORED, Dan”), and she maintains that same steadfast determination that helped define Teddy and Jenny Fields, latching onto their good memories in a way that becomes deeply sad, no matter her behavior. Had the film kept its infinitely superior original ending, their final moment together—with Close giving a sad, defeated look as he walks out the door—would have maintained its unbearable sadness, rather than being undermined by a boilerplate finale.

“Fatal Attraction” gave Close a chance to play the ostensible villain, but Stephen Frears’ delectably nasty “Dangerous Liaisons” allowed her to get downright catty as Marquise Isabelle de Merteuil. Introduced contemplating herself in the mirror self-lovingly, she’s a less transparently sordid character than John Malkovich’s Valmont but no less predatory. Where Malkovich’s open lasciviousness leaves little room for doubt as to what his intentions are, Close approaches each scene with an innocent character with a falsely welcoming smile; she lowers her head as if she’s letting Uma Thurman’s Cecile rather than orchestrating her ruin, taking on a concerned tone that only sounds cruelly mocking if one listens closely. She describes herself as a “virtuoso” of deceit, and what’s fascinating is how she manages to pull the wool over Makovich’s eyes even as she’s far more honest about her black-hearted treachery with him than with anyone else, apparently letting her guard down as she speaks (semi-honestly) of her love while letting a slight upturn in the corners of her mouth hint that she’s planning his destruction. It’s a thrill watching her get so much joy out of controlling the destruction of others, and it’s nearly as thrilling watching her face fall when she realizes she’s about to lose that ability altogether.

“Dangerous Liaisons” provided Close with arguably her best role. 1990’s “Reversal of Fortune” (pictured above) meanwhile, is the best film in which she’s appeared, as well as one of her most essential castings. Director Barbet Schroeder gets a lot of mileage out of the juxtaposition of Close’s mischievous, dryly funny narration as the comatose Sunny von Bülow and her impassive body, but he gets even more in flashback scenes between a boozing, depressed Sunny and her icy husband/future accused murderer Claus (Jeremy Irons, who won a richly deserved Oscar). Close carries herself throughout as a woman who’s simultaneously in control of her family’s destiny and slowly self-destructing, possibly by choice, keeping herself still while tearing into Claus in with a smile or a sly remark, then collapsing as her drinking gets the best of her. Sunny is the rich spouse, and the one with the old-money view that her husband shouldn’t deign to take a job. The actress plays their confrontations with a mixture of blueblooded arrogance and genuine unhappiness, turning over her accusations that he’s a “prince of perversion” and that she “didn’t marry you for this” into daggers while hugging herself in self-pity. By the time she slips fully into addiction, her final confrontation with Claus sees her manic, jaw moving a mile a minute while everything else remains still before she finally breaks down. In these scenes, we see both potential Sunnys simultaneously—hyper-controlling narcissist and pitiable addict, plausible murder victim and suicidal wreck—and it’s key to the film’s success.

Following a bizarrely stilted turn in “Hamlet” that’s improbably far worse than Mel Gibson’s work, Close spent much of the '90s veering back-and-forth between DOA prestige projects (“The House of the Spirits,” “Paradise Road”) and middling TV movies (“Sarah, Plain and Tall,” the pre-Don’t Ask Don’t Tell-set LGBT military drama “Serving in Silence”). Still, there are some gems in the period, including Istvan Szabo’s lovely “Meeting Venus.” Playing a Swedish opera star who’s initially unimpressed with the unknown Hungarian conductor (Niels Arestrup) leading a production of Wagner’s “Tannhauser,” Close embarks on a love affair with him. Their scenes together in hotel rooms show are incredibly tender, with Close wistfully smiling as she talks about how failed romances made her more gentle. If the film leans a bit too hard on their romance to symbolize the tenuous relationship of a reunited Europe, it never forgets the human beings struggling to make sense of a difficult romance in a new world, with Close’s heartbroken but not regretful pronouncements at their breakup suggesting the limits of trying to force a union. “Alright, it’s over. Go to hell. It was beautiful, it’s a pity it’s over.”

Most of Close’s best work in the ‘90s came in comedies, whether it was as a very funny Pat Nixon/Nancy Reagan hybrid in “Mars Attacks!” or a turn in “The Simpsons” as Homer’s long lost mother. Close received the most attention for her star turn as Cruella de Vil in the live-action remake of “101 Dalmatians.” The film itself is a bland “Home Alone” knockoff, but while Close can’t quite match her animated counterpart, she’s still by far the best thing about it, seemingly playing de Vil by way of Norma Desmond (a role she took on, and won a Tony for, in the musical version of “Sunset Boulevard”), all lunatic grins, flowing handwaves and exaggerated “daaahlings” as the megalomaniacal fashion goddess. She’s equally funny, and only slightly less broad, in Robert Altman’s “Cookie’s Fortune,” playing the pretentious playwright niece of Patricia Neal’s Cookie with a lilting southern belle voice and a constant judgmental grimace. Mortified by her aunt’s suicide (“suicide is a disgrace”), Camille is another one of Close’s controlling family heads, deciding the potential jailing of an innocent man is preferable to the personal shame she may face.

Her best comic performance came in 1994’s “The Paper” (pictured above), by far the best of Ron Howard’s comedies. As Alicia Clark, the managing editor of a scrappy NYC tabloid, Close is torn between her sympathies for the regular staff she used to be a part of and her duties to the bottom line; she sits in staff meetings with a cross-legged, leaned-back “I’m in charge” demeanor as she looks over the brim of her glasses, but still trying to get in jokes with her co-workers (on what to do after stepping over bodies: “I have a cigarette and go to sleep”). The film’s central conflict between her and Metro Editor Henry Hackett (a very funny Michael Keaton) over getting an accurate story vs. getting the paper done on time is further complicated by her ulterior motives—more money for expensive tastes—which Close physicalizes with an insistent lean and casually threatening tone when she mentions her potential job offers. What’s remarkable about Close’s work in “The Paper” is how she blurs Alicia’s self-interest and pragmatism without making her a monster, showing a woman who became controlling to self-justify her bad choices as she gradually makes her way to the right one.

After being bitten by the Altman bug, Close spent much of the early- to mid-2000s co-starring in ensemble-driven dramas. Though she does solid work in her two Rodrigo Garcia films (“Things You Can Tell Just By Looking At Her,” “Nine Lives”), her best work in the bunch is in Chris Terrio’s “Heights,” a somewhat self-serious everything-is-connected drama that nevertheless comes to life whenever she’s on screen. Playing an acclaimed actress dealing with A) her husband’s infidelities, and B) her belief that her daughter (Elizabeth Banks) is marrying the wrong man, Close finds a way to come off as both genuinely well-meaning and deeply controlling. A sidewalk conversation with Banks sees her brilliantly signifying slight alterations in intention over the course of a minute, first raising her voice in a “what’s the big deal?” tone as she pushes her daughter toward a nice guy, then letting her face and voice drop as she reprimands her daughter for not listening to her, then offering advice with a friendly smile before an offhanded cruel remark from Banks sees her eyes going darker as she turns away, wounded. Throughout the film, Close lets small shifts in her eyes and face show a woman coming to terms with her weaknesses and insecurities while trying to balance caring for her daughter and not smothering her, leading to a truly lovely, understated finale between the two.

While “Heights” gave Close one of her better film roles, the late 2000s saw her doing her best work on TV. After a memorable appearance as a Supreme Court nominee in a late episode of “The West Wing” (in which her work helps make up for a Supreme Court gamble that’s somehow dumber than “let’s hope the Republicans blink on Merrick Garland”), Close took on the female lead role in the fourth season of “The Shield.” As Captain Monica Rawling, close comes off as weathered and warm as she tries to clean up both the precinct and Los Angeles without alienating citizens or cops. Whether she’s interrogating an abusive foster parent with barely hidden venom or calling out her predecessor-turned-councilman’s self-serving reasons for cutting a deal with a dangerous drug kingpin through gritted teeth, Close suggests a decent cop who’s had to fight like hell to do the right thing in a rotten system, and who’s barely maintained her sanity and self-control doing it. At the same time, she lets an arrogant streak (and racial blind spot) show through as she flippantly dismisses concerns about her search-and-seizure program, which eventually leads to her downfall. Her relationship with Michael Chiklis’ Vic Mackey grows from tenuous to genuinely respectful, almost affectionate; their final scene together is one of the most moving of Close’s career as she takes on a motherly role, holding back tears just long enough to plead that he not go down the dark path that seems to await him. She’s done her best to do right in a lousy world, and her thanks are an unceremonious sendoff and the knowledge that what good influence she had, on the the city and on Mackey, was fatally limited.

A pair of remakes—2003’s “The Lion in Winter” and 2004’s wildly uneven “The Stepford Wives”—gave Close a pair of her classic villain roles, the first as the manipulative Queen Eleanor, whom she distinguishes from Katharine Hepburn’s version with a chillier take, the second as the psychotically chipper mastermind behind a reactionary society. Her best villain as of late, however, came with her other FX drama, “Damages” (pictured above) in which her high-profile attorney Patty Hewes represents vulnerable people by lying, cheating and far worse. Close’s mind games with Rose Byrne’s idealistic underling are that of a Machiavellian mother figure—her icy dismissals with a casualness that suggests she barely has time for anyone, her warm reassurances as her eyes suggest her smile isn’t entirely genuine—always lying just well enough to keep us in doubt as to her true feelings. Good and evil are passé to Patty; winning at all costs is all that matters, and Close makes that potentially limited story worth watching by showing its thrilling highs and its ultimately isolating lows.

Close has appeared in a number of genre films over the last decade, from big hits (“Guardians of the Galaxy”) to gargantuan flops (“Warcraft”). Most of her roles are small and not particularly memorable, but she stands out in the uneven but not uninteresting zombie drama “The Girl with All the Gifts.” As Dr. Caldwell, a cropped-hair-sporting military scientist who’s more than willing to test (read: kill) Sennia Nanua’s Melanie, a young girl afflicted with flesh-eating compulsions, despite her human behavior in order to save mankind, Close plays her role as someone who takes no pleasure in her task but little compunction in carrying it out. In her debates with Gemma Arterton’s more humane schoolteacher/researcher, she speaks with a tenor that’s both understanding and firm in its resolve, constantly rationalizing her choice to write off a by-most-appearances human life. Though she’s saddled with some of the most thuddingly expository dialogue in the film, Close imbues even the most cumbersome monologues with a coldly rational manner, as if her every moment sees her gearing up for the unthinkable. She can take charge and do what is necessary by killing her conscience, or else acknowledge the unthinkable and lose mankind.

Though she earned a pair of Emmys for her work on “Damages,” Close’s Oscar has remained elusive, with her most recent nomination coming for her 2011 drama “Albert Nobbs” (she lost to Meryl Streep’s near-worst work in “The Iron Lady”). Playing a woman who disguises herself as a man in order to escape violence and earn a decent life, the actress gives a technically accomplished performance, but the film (directed by frequent collaborator Rodrigo Garcia) never defines Nobbs beyond a desire to stay hidden for safety. The success of the performance depends on Close concealing her emotions and desires from others while projecting them to the audience; she succeeds at the former, but the latter never really happens, and the role comes off mostly as a stunt as a result.

“The Wife,” by contrast, shows exactly how that balancing act is achieved. In its early scenes, Joan’s reticence can easily be written off as simple shyness and discomfort in the spotlight, her long pause and faraway look as she listens to the news of his Nobel win a simple case of nerves. As the film carries on, however, her simple explanations of her clear discomfort ring true while not quite revealing the whole truth. “I don’t want to be thought of as the long-suffering wife” becomes more than just a simple point of pride, but a barely suppressed acknowledgement of her own contributions to their lives and success. With her careful elisions and studied responses, Close paints a portrait of someone who has relished being the most important person in her family’s life while chafing at the lack of acknowledgement of her credit within the family. The role is both atypical in its apparent recessiveness and ultimately of a piece with her body of work, a woman whose stillness and quiet bely a self-described “kingmaker.”

from All Content https://ift.tt/2PdTBjo

1 note

·

View note