#spittlebug nymph

Text

I love froghopper eggs

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I UHH UMM HMM

Pblblbbblbblllbbppbbb

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I love how one can find beauty in nature by just taking a closer look.

Many of you might have seen these little patches of froth on plants and maybe wondered why. The nymphs of the froghopper encase themselves in foam made from the plant sap while they feed for protection, which is why they are also known as spittlebugs.

#a trip to the us of a#nature#plants#leaves#animals#insects#spittlebug#froghopper nymph#raindrops#drops#fern#clover#oxalis#photography

1 note

·

View note

Text

Spittlebug nymph

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Summer Spittlebugs

This time of year it’s not unusual to be walking through a garden or meadow and suddenly come across what looks like a wad of spit or foam stuck to the stem of a plant. This wasn’t left by some uncouth person, nor is it the remnants of some pesticide or other chemical. Instead, it’s the active shelter of a spittlebug!

As the name suggests, these insects create these foamy conglomerations. They then use them as shelter while they feed on the sap of the host plant. There are literally thousands of species within the superfamily Cercopoidea, consisting of the three families Aphrophoridae, Cercopidae, and Clastopteridae. They’re also colloquially known as froghoppers, though the nymph stage that is found within the spit doesn’t yet hop.

The spit protects the nymphs in a few ways. It’s a visual cover to keep predators from seeing them. If a predator should try to eat the spit, nymph and all, it will find that the foam has a rather awful taste. And it can offer some protection from heat and sunlight on hot summer days. It’s made of waste material from digested sap; one nymph can cycle three hundred times its body weight in sap through its system in one hour.

While sap isn’t exactly a calorie-dense food, spittlebug nymphs have secret allies that were only recently discovered. It turns out that they have not one but two species of bacteria living in their digestive systems. In a symbiotic relationship, the bacteria take shelter there while helping the spittlebug acquire extra nutrition. How? By turning glucose from the sap into crucial amino acids that the nymph needs. Other insects that survive on sap also have these sorts of bacteria, but only one species each rather than two.

Adult spittlebugs are also pretty remarkable. They’re even better jumpers than fleas considering their larger size. Some still retain aposematic coloration that warns away predators. And while they may only live a few weeks after molting into their adult form, the females of some species can lay several dozen eggs before she dies.

Here’s the thing: the vast majority of spittlebugs aren’t going to seriously harm your plants. They don’t take enough sap, and aren’t going to hide in their foamy homes long enough to be a concern. If you have a LOT of them on one plant, they may cause a bit of distortion of the plant’s tissues, temporarily weaken its immune system or open it to diseases through the wounds, but this is a rare situation. And the spittlebug species that don’t produce bad-tasting secretions are potential food for other animals, so they do have an ecological role to play.

Occasionally species like the meadow spittlebug (Philaenus spumarius) may carry the bacteria Xylella fastidiosa which can cause widespread diseases in agricultural crops like Pierce’s disease or olive quick decline syndrome. But the plants in your garden are not likely to suffer the same fate, especially if you’re growing a nice variety of species rather than an entire plantation of one thing.

Finally, I want to advocate for biodiversity rather than the kneejerk reaction “It’s a bug on my plant–kill it!”. You want bugs in your garden (especially native species), because that means it’s an active ecosystem that supports local life. If you determine that you have a non-native species like the aforementioned meadow spittlebug, then all you need to do to get rid of it is hose down the affected plants as needed; pesticides won’t penetrate through the spit anyway, and a hose is faster, cheaper, and safer. Otherwise, native species of spittlebug are not going to cause you any issues, will be gone in a few weeks, and have a place in their ecosystem, too. So enjoy the fact that you’ve created a good home for wildlife, and marvel at these insects with a rather unique strategy for survival!

Did you enjoy this post? Consider taking one of my online foraging and natural history classes, checking out my other articles, or picking up a paperback or ebook I’ve written! You can even buy me a coffee here!

#spittlebugs#froghoppers#spit bugs#insects#bugs#invertebrates#wildlife#animals#nature#gardening#food web#ecology#ecosystem#scicomm#science communication#biology#science

93 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Meadow Spittlebug - Philaenus spumarius

The young Spittlebugs spend most of their lives hidden away in plant recesses covered in a frothy, foamy mass. In there, they can consume plant juices at their leisure, stay hidden from predators and avoid drying out. It’s their best choice to make since outside the foam they’re rather soft-bodied, lack defenses and aren’t too quick (as they lack the ability to hop and jump). But of course, they can’t stay young forever and eventually leave the foam after one final molt into adulthood, leaping off into the green beyond. That’s what this post is here to showcase: the fully grown adult Meadow Spittlebug, solid and fully developed, leaping around on (or around) the plants it once called home. Typically, I’ve found the nymphs nestled in goldenrod, but they apparently have a WIDE range of plants that they call food, and thus many hosts to froth up. Without goldenrod in our yards anymore, I’ve only see the occasional nymph, but year after year there have been many Meadow Spittlebugs to see, each one more unique than the last! As a quick search on Bugguide will show you, P. spumarius has a variable appearance in adulthood,

While researching this insect, I’ve found an illustration on Bugguide that effectively displays the variability of patterns (from a dorsal view) one could expect if searching for specimens. With their great range of body patterns featuring combinations of brown, white and black, I’m particularly fond of the more intricate ones or those whose wings are solid colors. So many patterns and colors, and yet they are all considered the same specie! It’s like the Asian Ladybug all over again. However, just like the Asian Ladybug, there must be some commonalities across most of the patterns that allows for effective identification. According to Bugguide, this specie has prominent wing veins (the ones closer to the body) and has either a predominantly black-colored body, or two small spots on the tip of their head, like two tiny nostrils. Being perfectly honest, I didn’t look for spots at first but after learning what to look for, I’m absolutely astonished! Such a small detail and the code was cracked! It’s not that simple for a photographer though, as the little hoppers don’t like to look at you directly and would rather zip away by hoping from plant to plant. Keep an eye out for them throughout the summer, and a second eye on any fruiting plants you may have for signs of damage.

Pictures were taken on August 26, 2017 and July 7, 2019 with a Samsaung Galaxy S4, and on June 16, 2021 with a Google Pixel 4.

#jonny’s insect catalogue#ontario insect#spittlebug#meadow spittlebug#hemiptera#auchenorrhyncha#true bug#insect#toronto#august2017#2017#july2019#2019#june2021#2021#entomology#nature#invertebrates

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Skumcikade (Aphrophoridae indet.)

Nymfe-skjul.

Spittlebug (Aphrophoridae indet.)

Nymph hide.

#Skumcikade#Skumcikade Aphrophoridae indet.#Aphrophoridae#Spittlebug#Næbmunde#Hemiptera#Insekt#Insect#Topbjerg#Sommer#Summer#Field#Mark

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A common ladybug species, these multi-colored Asian lady beetles inhabit various regions around the world. They move slowly on land but can reach speeds of up to 37 miles an hour in the air.

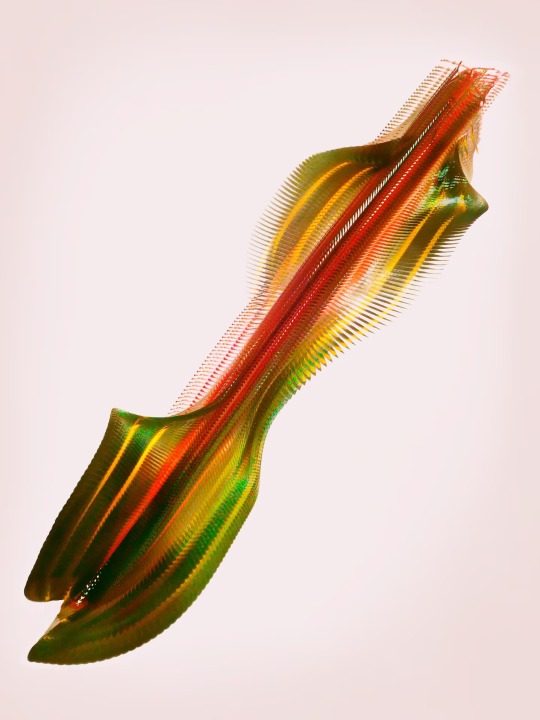

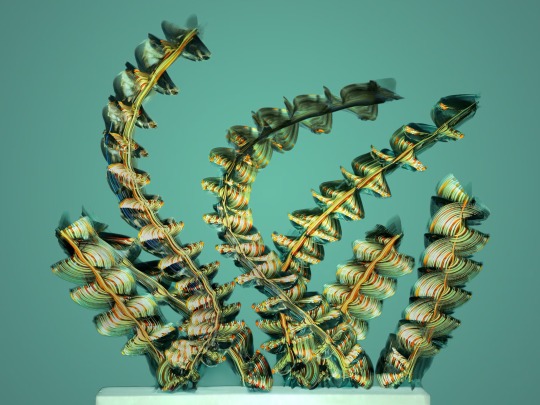

These Photos Are Works Of Art And The Artists Are Bugs

A Photographer’s Innovative Technique Reveals the Flight Paths of Insects in Exquisitely Alluring Ways.

— Photographs By Xavi Bou | March 25, 2024 | ByAnnie Roth

Movements of flying insects make them tough to track, but technological advances and some creative thinking have allowed Spanish photographer Xavi Bou to do just that. After spending 10 years concentrating on birds in flight for his Ornithographies project, he shifted his focus to bugs.

For Entomographies, he uses high-speed video footage taken by Adrian Smith, an entomologist at North Carolina State University, to decode and document insect trajectories. Then Bou selects multiple frames and merges them into single images that convey the rapid motions through space and time of one or more animals.

With Smith’s help, Bou has mapped the aerial acrobatics of wasps, the leaps of leafhoppers, and the flutters of butterflies in stunning detail. In doing so, he hopes to raise awareness about the decline of key insect populations worldwide. “It’s happening in front of our eyes, and we are not paying attention,” Bou says.

Zebra Longwing

This butterfly, found in many parts of the Americas, lives up to its name. The insect can soar to great heights with just a few beats of its supersize wings.

Two-Lined Spittlebug

This insect, native to the eastern United States, is often called a pest because of its taste for turf. Spring-loaded hind legs can launch the animal into the air like a rocket.

Yellow-Collared Scape Moth

Unlike most moths, this North American species can be seen flying during the day, with its iridescent blue-black wings that shimmer in sunlight.

Ailanthus Webworm Moths

These tropical moths have moved farther north in the U.S. Thanks to their larval host, the invasive tree of heaven, they are among the most widespread backyard moths in the country.

Common Stonefly

Found mainly in eastern North America, this insect spends time as an underwater nymph, often in forested streams or rivers. Then it emerges from its aquatic environment, molts into an adult, and gains its wings.

Green Lacewings

Eighty-seven species of this insect have been recorded in the U.S. and Canada. Because they have hearty appetites for unwanted plant visitors such as aphids and mites, they’re often used for biological control of pests.

Grapevine Beetle

This insect, with an apt name, feeds on the leaves and fruit of grapevines, both wild and cultivated, but it does little harm to the plants. A type of scarab beetle, it often flies in a curved path.

Oak Treehopper and Green Treehopper

Treehoppers are known for their distinctively shaped pronotum, the area behind the head, that often mimics parts of plants to provide camouflage from predators. Specialized muscles provide their jumping ability.

Banded Orange

This strikingly colored butterfly has a range that stretches from Mexico to Brazil. Before the mating season begins, males seek mineral salts, sometimes even drinking briny secretions from the skin, eyes, and nostrils of other animals.

Sapho Longwing

Longwings can live for six to seven months, a longer life span than most butterflies. This variety, ranging from Mexico to Ecuador, has lustrous blue on its wings, which inspired another of its common names: Sapphire longwing.

0 notes

Text

Meadow Spittlebug’s Record-breaking Diet Also Makes it Top Disease Carrier for Plants

New study finds that the meadow spittlebug can feed on more than 1,300 plants, revealing scope of its capacity to spread incurable plant disease to crops

New research fueled in part by citizen scientists reveals that the meadow spittlebug—known for the foamy, spit-like urine released by its nymphs—can feed on at least 1,300 species of host plants, more than twice the number of any other…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

@icouldreallyuseanewurl submitted: Hi! I saw these two having some fun! I'm fairly sure they are tiger crane flies in the american mid-west :]

They are! Making more tiger crane flies! Good for them. Shout out to the little blob of foam from a spittlebug nymph

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

30 Days Wild, Days 6-8

Been pretty frazzled over the last few days, so didn’t get around to posting on Tumblr.

Anyway, day 6 was pretty frantic, so I only had time for a quick breather in the garden for my ‘wild’ activity for the day. Still, certainly wasn’t a waste: I saw that the Japanese Wisteria had flowered, and I spotted some moths:

I believe the moth in the middle is a Garden Carpet, while the tiny moth on the left is probably a Common Marble

Day 7 was a little slower, but quite overcast - I wasn’t able to spot much fluttering about on my walk in the garden. I did however spot that a lone strawberry plant had survived the neglect of our strawberry patch, and sported a little spot of foam on one of its leaves:

This is the home of the nymph stage of a froghopper, and here in the UK we call this foam ‘cuckoospit’ because it starts appearing at around the time you start to hear cuckoos in the spring. I recently saw that one of the UK tabloids was spreading misinformation about it being poisonous or something - it is completely and utterly harmless. It just provides a nice home for the little ‘spittlebug’ developing inside. I mean, I doubt it tastes very nice, but I’m not one to go around licking globs of foam off of plants.

As I saw people pointing out on Twitter, it kind of sucks that misinformation about bugs is getting plastered across newspapers while we’re facing major species decline here in the UK.

Today, I spent quite a while out in the garden, working on building my bug hotel:

I’ll fully admit that I’m no carpenter, but I’m pretty proud of the effort anyway - it’s relatively sturdy given that it was made out of recycled wood from old pallets.

I’m still looking for a few more materials to finish it out, but in the meantime it has:

- a ‘log’ pile for woodlice and centipedes

- drilled wood and sawn bones for solitary bees

- dry leaves and rotting wood for leaf-litter critters

- soil for soil-dwelling critters

- holey bricks and broken pots for amphibians, slugs and snails

- horseshoe for good luck

I also spotted an Azure Damselfly hovering around the Mexican Orange Blossom plant - gotta love that vibrant blue colouring!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Une nouvelle espèce d'un nouveau genre vient d'être décrite dans la super-famille des Cercopoidea (dont fait partie la famille des cercopes), Araeoanasillus leptosomus gen. et sp. nov., à partir de...

See on Scoop.it - EntomoNews

Araeoanasillus leptosomus gen. et sp. nov., (Hemiptera, Cercopoidea, Sinoalidae?), a New Froghopper from Mid-Cretaceous Burmese Amber with Evidence of Its Possible Host Plant

by George Poinar, Jr.

Department of Integrative Biology, Oregon State University,

Life

Published: 31 March 2023

(This article belongs to the Special Issue Recent Research on Palaeontology)

[Image] Holotype of Araeoanasillus leptosomus gen. et sp. n. in Burmese amber. (A)—dorsal view; (B)—ventral view; (C)—lateral view. Arrowhead shows tip of abdomen. Scale bar for (A,C) = 1.0 mm; for (B) = 1.3 mm.

-------

NDÉ

D'après l'étude

Une nouvelle espèce d'un nouveau genre vient d'être décrite dans la super-famille des Cercopoidea (dont fait partie la famille des cercopes), Araeoanasillus leptosomus gen. et sp. nov., à partir de l'ambre birman du Crétacé moyen.

La superfamille des Cercopoidea — proche parente de celle qui inclut les cicadelles et de celle qui inclut les membracides — comprend actuellement cinq familles existantes (Aphrophoridae Amyot et Serville, 1843 ; Cercopidae Leach, 1815 ; Clastopteridae Dohrn, 1859 ; Epipygidae Hamilton, 2001 ; et Machaerotidae Stal, 1866) et trois familles éteintes (Cercopionidae Hamilton, 1990 ; Procercopidae Handlirsch, 1906 ; et Sinoalidae Wang et Szwedo, 2012) [1,2].

Le nouveau genre Araeoanasillus possède les caractéristiques suivantes : corps mince, de taille moyenne (longueur 7 mm) avec tête plus longue que large, yeux ronds ; antennes minces avec huit antennomères ; pédicelle très court, plus court que le scape ; pronotum avec un rapport longueur/largeur de 2. 4 ; métatibia avec trois épines, dont une épine courte près de la base et deux épines adjacentes, longues et épaisses près de l'apex ; une seule série de 16 dents apicales épaisses (peigne) à l'apex métatibial ; [...]

Les membres existants des Cercopoidea, ont deux types de comportement au cours de leur développement. Alors que les nymphes, dénommées "spittlebugs" en anglais, produisent de l'écume et se nourrissent dans cette masse de bave mousseuse — que l'on appelle le « crachat de coucou » — qui masque leur présence, les adultes ailés, appelés en anglais "froghoppers", n'ont pas cette protection.

Bien que nous ne sachions rien de la biologie des individus de cette famille éteinte (préférences alimentaires, comportements de recherche de nourriture, parasites, capacité des nymphes à produire de l'écume au cours de leur développement), le présent spécimen nous donne des indices sur son hôte végétal possible. Les trichomes végétaux uniques adjacents et attachés au fossile suggèrent que le "cercope" s'est nourri et a probablement pondu sur des fougères.

0 notes

Photo

Taken 2022 31st August, this was a European alder spittle bug (Aphrophora alni) I found on the bus. In Sweden, they occur wherever forest edges, hedgerows, meadows, gardens, and parks are present. Contrary to their name, these spittle bugs don't only feed from alder trees as bushes and trees of different species are also taken, with adults prefer deciduous trees while larvae prefer herbaceous plants. They can be seen from May-October, with their life-cycle beginning in spring hatching from eggs laid close to winter. The nymphs live on the stems and leaves of herbaceous plants protected from exposure by a foam made from plant sap until they've reached their imago stage. Eventually, females will mate and will deposit her eggs on herbaceous plants close to winter, where they overwinter until the following spring starting the cycle over. #animal #animals #djur #natur #naturliv #wildlife #insect #insects #insekt #insekter #nature #spittlebug #spittlebugs #bugs #bug #arthropod #arthropods #invertebrate #invertebrates #truebug #truebugs #insectagram #animalia #arthropoda #insecta #hemiptera #aphrophoridae #aphrophora #aphrophoraalni #europeanalderspittlebug https://www.instagram.com/p/CnSQ_p7Kw_T/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#animal#animals#djur#natur#naturliv#wildlife#insect#insects#insekt#insekter#nature#spittlebug#spittlebugs#bugs#bug#arthropod#arthropods#invertebrate#invertebrates#truebug#truebugs#insectagram#animalia#arthropoda#insecta#hemiptera#aphrophoridae#aphrophora#aphrophoraalni#europeanalderspittlebug

0 notes

Note

Can you assign me a fursona too please?

Look at this one

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mystery Spit

Spittlebug froth on the stalk and leaf stem of a sneezeweed plant.

You’ve likely noticed the stuff at this time of year even if you didn’t have a ready name for it – grape-sized globs of frothy white foam on all kinds of plant stems.

The bubbles are made by the nymph stage of a large group of insects known commonly as frog hoppers, and scientifically as members of the widespread insect superfamily Cercopoidea.

Because the activity of the nymphs is so noticeable, they’ve earned their own common name – spittlebugs.

A spittlebug temporarily removed from its frothy shelter.

The nymphs, which hatch in the spring from eggs laid the previous summer, are sap drinkers. They pierce plant stems to access the juices produced by the growing plant, drink deeply, and after processing vital nutrients, turn their waste stream into a protective shelter. Although spittlebug froth visually resembles spit, it contains no saliva. The bubbles are mixture of the tiny creature’s urine and a sticky fluid produced in an abdominal gland.

The frothy layer keeps the soft-bodied insects from drying out and it also serves as a predator barrier. Because spittlebugs produce urine in amounts more than 150 times their own body weight, their bubbly shelters generally offer ample protection.

Research about spittlebugs has been conducted at University of British Columbia. Information about this research, including a short video narrated by New York Times Science Writer James Gorman can be found at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/19/science/spittlebugs-bubble-home.html

Patrick McShea works in the Education and Visitor Experience department of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

106 notes

·

View notes