Audio

See above a podcast that provides an easy guide to cloud computing and the risks and benefits of using it in law firms.

Source: https://lso.ca/lawyers/practice-supports-and-resources/topics/technology-practice-tips/cloud-computing-introduction

0 notes

Text

Intelligence as a curse - Who is watching you while you binge-watch?

A study conducted by researchers from Northeastern University and Imperial College revealed that smart TVs pass data to third parties including Google, Facebook and Amazon (‘study’). In 2015, 68% of US households had at least one connected TV device. Their role within homes raises important questions about their privacy implications and compliance with data protection legislation, particularly the General Data Protection Legislation (‘GDPR’).

How do smart TVs collect data?

Smart TVs are TV devices that are connected to the internet allowing their users to access streaming services such as Netflix and access a host of other online services. A technology called Automatic Content Recognition enables TV manufacturers to track users’ viewing activities in order to provide them with personalised recommendations. The study found that viewing information was also sent to third parties including third party advertisers, who can use viewing behaviour in conjunction with additional consumer data to provide targeted advertising. Their position within family homes means that targeted advertising might be supplied to both parents and their kids.

Compliance with the GDPR

The study found that data collected and transferred included device location at a city or state level, unique identifiers (MAC addressed, device ID) and device names consisting of users’ names (John Smith’s TV). Under the GDPR, data constitutes personal data where it can be used to distinguish one individual from another. Since the purpose of data collection in the context of smart TVs is the creation of a unique customer profile, it will be hard to argue that data collected by smart TVs does not fall within the definition of personal data, especially where parties receive users’ name and location.

Many smart TVs operate on an opt-out basis i.e. the default setting is that users consent to the collection of personal data unless they explicitly opt-out. Amazon is one example of a manufacturer that applies an opt-out default setting for its Amazon Fire TV. Upon reviewing the privacy settings of my own smart TV, from manufacturer LG, it transpired that it applied an all-or-nothing approach whereby users can either accept the entire privacy policy or not use any internet services at all. Both an opt-out and all-or-nothing approach are contrary to the GDPRs’ requirements for consent, which sets out that consent must be specific and given freely by means of a positive opt-in. Therefore, the benefits of valid consent, such as individuals’ ability to control use of their personal data, are diminished.

The road ahead

It is to be hoped that further research will be conducted to ascertain in more detail the categories of data received and transferred in the context of smart TVs. Some countries have already taken steps to address data protection concerns, most notably the Netherlands whose data protection authority has not only investigated three major TV manufacturers, but also labelled data processed by smart TVs as sensitive given their position within homes and the inferences that can be made about someone’s personal life and background based on their viewing habits.

0 notes

Text

Case comment: Data breach class actions – Court of Appeal decision in Richard Lloyd v Google LLC

On 2 October 2019, the Court of Appeal of England and Wales published its judgment in Richard Lloyd v Google LLC reversing the High Court decision and allowing the claimant to proceed with a representative action against Google for breach of the Data Protection Act 1998 (‘DPA’). The decision is a loss for Google but a victory for approx. 4 million UK consumers who had their data collected and sold by Google without their knowledge.

Background

The claim focuses on a technology used by Google during 2011 and 2012, commonly known as “Safari Workaround”, which allowed Google to circumvent Apple’s privacy settings and collect personal data without consent.

The parties do not dispute that there has been a breach of s.4(4) of the DPA, the question at stake is whether this contravention warrants compensation under s.13 of the DPA. The courts also had to decide whether the claim could proceed as a representative action under CPR Part 19.6, whereby all affected users are included automatically as claimants, regardless of whether they are aware of the proceedings or the infringement.

Court of Appeal

The Court of Appeal, delivering a unanimous decision, granted the appeal on the following three grounds:

1. Damages under s.13 of the DPA

The DPA has to be construed in line with EU law, which states that member states shall provide effective remedies where EU citizen’s rights have been infringed. In this case the only effective remedy is compensation and the claimants do not need to demonstrate any pecuniary loss or distress to qualify for compensation.

2. Same interest under CPR 19.6

In order to proceed as a representative action, all members of the class must share the same interest. The members of the class have all suffered the same alleged wrong, namely a loss of control over data, and therefore all share the same interest for the purpose of CPR Part 19.6.

3. Court’s discretion

The case does not amount to “officious litigation”, as stated in the High Court (para.103). Rather, the claimants are exercising their right to hold Google accountable and the Court of Appeal exercised its discretion to permit the appeal.

Comment

The decision of the Court of Appeal is to be welcomed for several reasons. The Court of Appeal recognised the value of data to both corporations and individuals, despite the fact that such value might not always be financial. If the appeal had been dismissed the millions of users affected would not have been able to seek any other practical remedies. Alternative remedies mentioned by the High Court judge, such as erasure or rectification of data, are not effective where data has been collected unlawfully and are not remedies but rather general rights available to data subjects even where no breach has taken place. Addressing the floodgate argument, representative action is time-consuming and expensive so will probably only be pursued where no investigation is launched by the ICO and courts can distinguish future cases considering the amount and nature of the data concerned in the Google case.

#case comment#privacy and web technolgies#cookies#targeted advertising#Safari workaround#Google data breach#data protection#week8

0 notes

Link

Interesting comment on two recent CJEU decisions considering the question of territorial scope of injunctions ordered by national courts against intermediaries. Both seem to open up the possibility of national courts ordering worldwide injunctions, subject to certain conditions set out in the two decisions.

The decision in Google v CNIL offers a more balanced approach requiring courts to balance conflicts between the freedom of expression and information and freedom of data protection and privacy. It’s a shame that the CJEU in the Glawischnig case did not put the same emphasis on this balancing task. Instead, it imposed a broad and vague obligation on Facebook to remove content with an “equivalent meaning” to the unlawful content, possibly allowing the removal of lawful content.

#intermediary liability#online content liability#Article 17 GDPR#Article 15 e-Commerce Directive#CJEU decision#week7

0 notes

Video

twitter

According to the 2019 Global Internet Phenomena Report published by network intelligence firm Sandvine, file sharing accounts for 30.2% of total upstream volume of global traffic, which is an increase of over 8% from the previous year. In view of more companies such as Apple and Disney launching their own streaming services, consumers might find themselves unable to pay for separate streaming services to access the content they want to watch and will resort to file sharing networks such as BitTorrent.

#reasons for piracy#affordability of legal content#return to piracy#future of streaming services#the legal fight against piracy continues#week6

0 notes

Text

Dare to share - copyright ownership on social networking sites

Social networking sites (’SNSs’) play an increasingly important role in society. A study conducted by Ofcom in 2019 revealed that 93% of 16 to 24 year olds in the UK have a social media profile. SNSs act both as a way of communication and a valuable platform for photographers and other creators to showcase their work. In a report published in 2015, the UK IPO suggests that social media plays a role in facilitating intellectual property infringement. SNSs do little to educate their users and the law seems inapt to deal with the variety of content created and shared on SNSs.

Identifying ownership

Under the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (‘CDPA’) copyright ownership vests in the creator of the work (section 11(1) CDPA). In the case of images, the person who took the image will usually be the creator. While this might be simple in an offline scenario, in the context of SNSs the question of ownership is anything but straightforward. Content can be reposted numerous times making it difficult to identify the original source. Where content goes ‘viral’, i.e. is viewed or shared millions of times, it might become nearly impossible to track down the original source as well as pursue each infringer.

Selfie dilemma

Selfies have become a popular tool to take images. Following copyright law, the copyright holder will be the person who took the selfie. This has led to obscure claims, such as the Monkey Selfie case where a photographer argued that he owned the copyright in an image taken by a monkey. Another example is the legal debate about who owns the copyright in the infamous Oscar selfie taken by Ryan Reynolds but initiated by Ellen DeGeneres. In such cases, unresolved questions of ownership curtail the ability of third parties to use the image, unless their use can be shown to fall within the scope of fair dealing.

Filters and derivative works

Further questions are raised by the use of filters or other photograph enhancement applications and whether their use could lead to the creation of a derivative work i.e. a new copyright protected work. The UK IPO has provided guidance stating, “that it seems unlikely that what is merely a retouched, digitised image of an older work can be considered as ‘original’”. This suggests that in most cases the use of photo enhancement tools would not warrant the necessary creative input to meet the originality requirement. Despite this, such tools are widely available on most SNSs without making users aware of their copyright implications. Instagram’s copyright policy does not mention filters once.

Risk for users

Copyright ownership has become more complex as online content has developed in ways not envisaged by copyright legislation drafted long before the rise of SNSs. The risk of infringement is transferred onto users who are not provided with clear guidance by the law or SNSs who profit from users sharing content, regardless of the lawfulness of such sharing.

#copyright#socialmedia#copyrightinfringement#copyrightandselfies#thinkbeforeyoushare#oscarselfie#copyrightownership#week5

1 note

·

View note

Link

Fair use in theory vs fair use in practice

Real-life example, which shows that for most social/content sharing networks such as Youtube, Facebook and Instagram the first step when receiving a copyright infringement complaint is to take down the content, without giving contributors a chance to respond.

#copyright#copyright infringement#fairdealing#copyrightincyperspace#copyrightandinnovation#fairdealingandinnovation#too big to fail#week4

1 note

·

View note

Link

Source: UK Intellectual Property Office

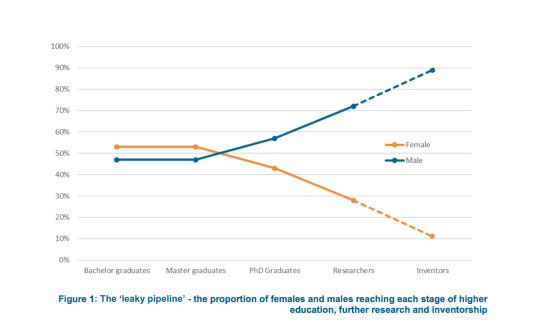

Meanwhile, the Indian government has decided not to wait for the industry to change but has taken active legal steps to make it easier for start-ups and women to file patents successfully. It has proposed amendments to its patents law that would introduce mechanisms such as reduced filing fees and expedited examinations.

1 note

·

View note