Photo

This year, Grey Bruce Chinese New Year Celebration has received a Multicultural Community Capacity Grant from the Government of Ontario. With the moderate amount of funding, we are able to enrich the programming of all the events with some traditional Chinese festive elements, and distribute posters of the events to more communities. As well, we can afford the traveling expenses to visit and connect with Chinese businesses through out Grey Bruce!

#Chinese Canadian#canadian chinese#chinese in rural canada#Owen Sound#Grey Bruce#grey county ontario#bruce county ontario#chinese in grey bruce#Chinese New Year celebration#tom thomson art gallery#grey roots museum#owen sound & north grey union public library#heritage place#Owen Sound Hub#city of owen sound#Grey Bruce Chinese heritage & culture association

0 notes

Text

A Comparison: Early and Recent Chinese Settlers in Owen Sound

Chinese have been living in Owen Sound for over 120 year. As time passed, the size, demographics and life of the Chinese population have changed. There is remarkable distinction between those who came to Owen Sound before and after late 1960s. The differences can be explained by the political, social and economic situations of the countries of origins of the immigrants, the changes in immigration policies, as well as Owen Sound's positive shift in attitude towards newcomers.

When the Head Tax failed to put a stop to Chinese immigration, the federal government passed the Chinese Immigration Act(a.k.a. Exclusion Act) in June 1923 to close the door to Chinese immigrants once and for all. The Act was repealed on May 14 1947 after the Chinese community had shown its loyalty to the country by participating in WWII. Still, it was only after much lobbying before the government agreed to revoke the Act. It was not until 1962 that Canada's immigration policy reopened door to Chinese immigrants. There were few arrivals to Owen Sound between 1920s and late 1960s. They had come to Canada before 1923 and lived in other parts of the country. They shared the same socioeconomic backgrounds as the early Chinese settlers in Owen Sound.

Chinese settlers of Owen Sound between late 1800s and late 1960s came from Guangdong Province, China and spoke Cantonese; they were male immigrants who knew very little or no English. Most of them had not gone to school back home. Because of the Head Tax and the Chinese Immigration Act, the Chinese community remained as a bachelor society for almost three decades. They came to Owen Sound with very little money. Consequently, these Chinese men invented or inherited occupations which required minimum contact with the English speaking customers – hand laundry or restaurant. They lived in the time when most Owen Sound residents knew very little about Chinese culture. These early settlers experienced significant social segregation.

After the Exclusion Act was repealed, Chinese immigrants were able to bring their families over or return to China and get married then come back with their new brides. Chinese children born in Canada receive education and job opportunities their parents and grandparents did not have; they are equipped to break out of the social segregation. On October 1, 1967, Canada liberated her immigration policy to allow admission to the country according to education, occupational skills and other criteria. Chinese professionals and skilled workers from different lands and cultures started to arrive in Canada. The Investment Canada Act passed in 1986 attracted investors and entrepreneurs from Hong Kong and Taiwan, and in recent years from China. Meanwhile, there was an influx of Vietnamese refugees between 1975 and 1985; a lot of them were of Chinese heritage. All through the 1990s, there was a significant number of immigrants from Hong Kong who had left there homeland because of political uncertainty. In the past 50 years, Canada has seen growing number of half-Chinese families as couples of inter-racial marriages are no longer punished by laws.

Canada's societal progress since the late 1960s has resulted in significant changes in the Chinese population in Owen Sound. Today, our Chinese community is made up of individuals and families of a wide age range --- from newborns to seniors; some are immigrants --- from different places like China, Hong Kong, Singapore, South Africa, Taiwan and Vietnam --- and others first or second generation Canadians. Their mother tongues are Cantonese, Mandarin, Malay and English. In some families, both parents are Chinese; in others, only one parent is. There are also non-Chinese families who have adopted children from China. All, except very few, of the adults have at least high school level of education either from their countries or origin or Canada; some have attended college and university. While some are in the stereotypical occupation as owner of or working in Chinese restaurants (Chinese laundry has been completely faded out in the 1970s), many Chinese in Owen Sound work in a variety of fields such as operating other kind of business like convenient store and clothes alteration and working as professionals or skilled workers for companies that are not Chinese-owned. Through work and school, Chinese and non-Chinese residents come into contact and learn about the culture and heritage of one another. Surprisingly, a lot of non-Chinese residents have association with Chinese culture through work, travel or marriage(their children have married Chinese). The understanding and integration lead to the break down of the social segregation which the early settlers experienced. In view of the increasing number of new immigrants from different countries arriving in the past decade, Owen Sound is gradually improving its capacity in supporting newcomers. That was not available to the Chinese who came 120 years ago.

Life in Owen Sound has advanced considerably for Chinese settlers throughout the century, allowing more and more social mobility and integration. Such progress, however, is not without its own struggles. The Chinese community is challenged in retaining its heritage, language and traditional culture among its younger generations. Fortunately, ever since Canada adopted multiculturalism as an official policy in 1971, institutions such as school boards and government cultural agencies have had a mandate to encourage Canadians to learn about the cultures of different ethnic communities, their own and others'. In Grey Bruce, Chinese heritage and culture activities in elementary schools are very well received. Events like the local Chinese New Year Celebration, organized by the Grey Bruce Chinese Heritage & Cultural Association in partnership with Grey Roots Museum & Archives, Owen Sound & North Grey Union Library and Tom Thomson Art Gallery, has been gaining community interest since it started in 2013. Such support and popularity encourages the younger generations in the Chinese community to learn more about their own heritage.

0 notes

Text

Making Owen Sound Home

The first Chinese came to Owen Sound in 1896. Lee Wing set up a hand laundry in part of Lot 8 on Poulett Street E (963 2nd Avenue East). Likely, his arrival was no great surprise to the town, since national section of the local newspapers had been reporting Chinese railroad workers in B.C. and their eastward migration. Cautious sentiments began to develop in as early as 1883; Melba Morris Croft wrote in Forth Entrance to Huronia “The question of Chinese immigration was of some concern 'now the CPR is pushing through. Our people will be out of work as the Chinese accept lower wages'”. However, townsfolks soon realised that their concern was unfounded.

1896 through the 1920s, the Chinese settlers in Owen Sound either owned or worked in hand laundries or Chinese restaurants, except for a couple of them who were domestic servant and hired cook in a hotel. Having little or no English, they did not seek employment with local businesses. It is true that Chinese business owners only hired their fellow countrymen. However, even given the option, the local labourers probably would not want to work in Chinese laundries and restaurants where Chinese, an alien language to them, was the medium of communication among workers. In both sectors of the population, language barrier determined the decision on who to hire and for whom to work.

For the most part, Owen Sound in the early 1900s has shown its acceptance towards the Chinese immigrants. However, the anti-Chinese wind did blow east and at times manifested itself in hate crimes. One such incidence was an unprovoked assault on Soon Lee in 1901. Social segregation was undoubtedly an aggravating factor of racial discrimination. The gap existed between the two cultures was the breeding ground for fear, speculations and misunderstanding. The Chinese immigrants chose to keep to themselves because they did not have the tool to communicate with people outside of their own Cantonese speaking community. Some might have wanted to learn English but there was no opportunity, not until the 1910s. There was record of an English class of seven Chinese at Knox Presbyterian Church in 1912. Also, circa 1915, Soon Lee was among sixteen Chinese who received one-on-one tutoring in an English class at Division Street Church. His teacher was Ms Kate Andrew. The English classes provided opportunities for the Chinese students and their volunteer teachers to learn about, understand and appreciate one another’s culture.

Fast ward to the recent 30 years. The second and third generations of the early Chinese settlers did not inherit the language barrier from their parents. Among the new comers, some have already acquired the language proficiency to work and live in an English-speaking environment before coming to Owen Sound. For new immigrants who want to learn or improve their English, resources such as ESL tutors and the Library's literacy program are available. Within the Chinese community, those who have better English help the others whenever needs arise. The existence of a common language allows the Chinese residents to make friends with others in the community and learn about their culture. A remarkable number of Owen Sound residents have visited Chinese communities in other parts of the world; some have even worked and lived in them. They return to Owen Sound with better understand of and heightened interest in Chinese culture. The undesirable elements in the gap between the two cultures are gradually being replaced by mutual acceptance and appreciation.

0 notes

Text

Arriving in Grey Bruce

The first Chinese presence in Grey County was recorded in the Union Publishing Co.'s Farmers and Business Directory for the Counties of Bruce Grey Muskoka, Ontario and Simcoe for 1896 Vol. IX --- Wing Hing Laundry in Meaford and Lee Wing Laundry in Owen Sound. Two years later, Durham saw its first Chinese resident Wah Lee, who owned and operated the New Chinese Laundry (The Durham Chronicle, August 1898). In 1901, another Chinese laundryman, Lee Toy, arrived in Grey County to reside in Bentinck. In the same year, Chinese also reached some Bruce County towns --- Chesley, Lucknow, Paisely, Teeswater, Walkerton. More Chinese came in the next decade; by 1911, Chinese immigrants were living in 19 towns throughout Grey Bruce, adding Stokes Bay, Hanover, Kincardine, Port Elgin, Southampton, Thornbury, Wiarton, Carrick, Dundalk and Markdale to the list.

These first Chinese residents in Grey Bruce shared three common characteristics: they all operated hand laundry(the exception was Ah Sing in Stokes Bay who seemingly worked in a stone quarry); they knew very little to no English; and they were all men.

Hand laundry as an occupation was invented by Chinese men living in Victoria, B.C. during the time when the CPR was being built in the 19th century. In view of the often life-threatening work conditions, a few of the Chinese railroad workers started looking into finding an alternative means to generate income. All railroad workers were men, most of whom were reluctant to do the chores which was considered to be woman's work. Unsurprisingly, the offer of washing clothes in exchange for a minimal fee was well received in the “bachelor society”. To set up a hand laundry in the railroad camp, all a person needed was to have access to water and the means to boil it.

During the Gold Rush, the Chinese were only allowed to take over mines which had almost been depleted by the white gold panners. Working on the railroad, the Chinese workers were assigned the most dangerous tasks for only half of the wages their Irish counterpart received. Consequently, after paying for necessary expenses and sending money home, the Chinese immigrants remained poor. When systemic racial discrimination forced the Chinese to move east, they left with very little money.

Chinese who came to Canada in the 19th century were peasants and farmers from the southern part of China. They did not know how to read or write in their native language, let alone English. There would be one or two in the railroad camp who were literate. They wrote letters home for the others, helping them maintain the bondage with their families. Working on the railroads. the Chinese immigrants had neither need nor opportunity to learn English. Venturing out of British Columbia, they knew they would arrive in towns and cities where everybody spoke English, and no one spoke Chinese. Because of the language barrier, they did not hold their hopes high in finding employment. Instead, with the little money they had, they would start their own hand laundry business. Even though the business had become more sophisticated, requiring indoor workspace and some proper equipments, the start-up cost was still affordable for the Chinese immigrants. The occupation was labour-intensive and time consuming, but it was the only viable one. Coincidentally, there was a growing need for such service, as towns in Grey and Bruce Counties were starting to develop and gain its significance as ports and agricultural produces suppliers to cities and larger towns in Southern Ontario, thanks to railway and steamboats. At its peak, Owen Sound had seven Chinese laundries (Vernon's Town of Owen Sound Directory 1917). No longer one-man operations, most of them were being run by father-and-son team, brothers, or cousins. In 1911, there were 22 Chinese living in Owen Sound; two of them worked as cook in a hotel and for a private family, the rest were laundrymen (Census Canada 1911).

More than 2 decades after the railroad era, and over 4,000km away from Victoria B.C., something had remained unchanged. Chinese in Grey Bruce lived in a “bachelor society”. Census Canada 1911 data reveals that among the 22 Chinese residents in Owen Sound, there was only one woman. Luise Die(38) was the wife of Z Chew Die(39) and mother of Hinsoo Die(2); the family live on 10th Street West, where Z Chew worked as a cook for a private family. Unlike immigrants from other countries at the time, Chinese men left their wives and children behind to go aboard for work. They would send home money, and put aside some to hopefully save up enough someday to bring the family to Canada. With the low wages they were making, it would take them years to accumulate the needed amount. The challenge increased greatly when the Canadian Government started to impose Head Tax on all Chinese immigrants, with the exemption of students, teachers, missionaries, merchants and members of the diplomatic corps. In 1885, every Chinese entering Canada had to pay $50 Head Tax. A Chinese labour at the time earned $225 a year; deducting all necessary expenses, there was only $43 left to split between money to send home and to save. The Head Tax increased to $100 in 1900, then $500 in 1903. Family reunion became an impossible dream for most. In 1923, the Chinese Immigration Act, also known as the Chinese Exclusion Act, was passed, putting a stop to Chinese immigration for 25 years until the Act was repealed in 1948. From the Gold Rush days to the Act being repealed, Chinese men all throughout Canada had lived dominantly in “bachelor societies” for 90 years.

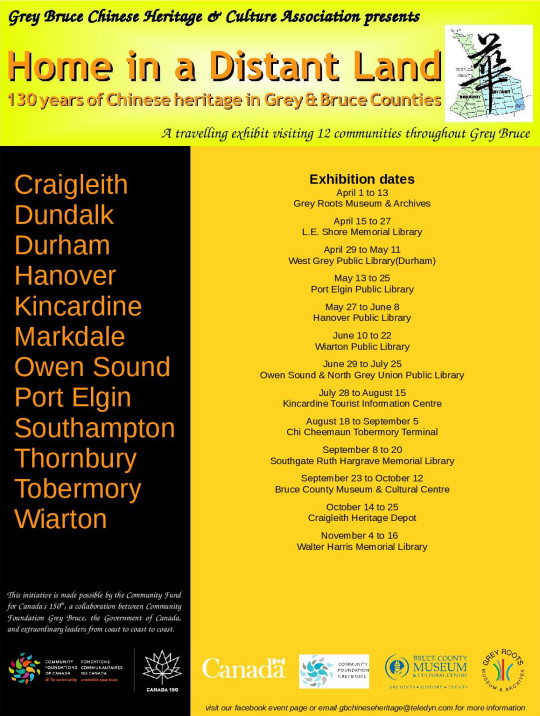

This article was first published in a column in Owen Sound Hub. The column is one of the three components of the Chinese heritage project Home in a Distant Land, which was made possible by the Community Fund for Canada 150th, a collaboration between Community Foundation Grey Bruce, the Government of Canada, and extraordinary leaders from coast to coast to coast. The column is complementary to an exhibit which travels to 12 communities throughout Grey Bruce. The third component of the project is a series of presentation in elementary schools and at public libraries

#Chinese in Canada#Chinese Canadian#Chinese in Grey Bruce#Chinese in Grey County#Chinese in Bruce County#Chinese in Owen Sound#History of Grey Bruce#History of Grey County#History of Bruce County#History of Owen Sound Chinese immigrants

0 notes

Video

youtube

Celebrating cultural diversity at Grey Bruce One World Festival 2017

0 notes

Text

How it all began

A long time ago, in a land far away, 50 men embarked on a journey --- one which took them three months across the ocean --- to a place that bore no resemblance to home. 70 more followed the next year. Recruited by British Captain John Meares in 1788 and 1789, these men sailed from Canton, China to Nootka Sound on Vancouver Island, British Columbia to work at a British fur trading post building a dockyard, a fortress and a 40-tonne schooner, the North-West America. Their whereabouts became unclear after their imprisonment by the Spanish during the Nootka Sound Crisis. One theory is that while some managed to find their way back to China, the rest remained and was assimilated into the First Nations community. The other speculation is that they were taken to Mexico by the Spanish and became slaves there. Anyhow, their footprints marked the beginning of an immigration story older than the Canadian Confederation.

In China after the mid-1700s, the once prosperous Qing Dynasty (1644 – 1912) began to decline. People's livelihood was greatly disrupted by natural disasters – droughts, famine and floods, as well as political instability caused by both internal and external threats. The southern sea ports experience an influx of farmers and peasants seeking work. They had left their families behind in villages near and far where they came from. Many of these men signed up with companies who had promised them work overseas and the prospect of wages to send home. In the one and a half centuries that followed, mining, railroad building, work in hand laundries, plantations, restaurants and other labour-intensive occupations brought many Chinese fathers and sons to Canada, the United States, Australia, South Africa and countries in South East Asia.

In the early history of Chinese immigration to Canada. All the voyages from China were destined for Victoria, British Columbia. Throughout the 1880s, Chinese was probably the second largest ethnic group there after the First Nations. However, the white minority which constituted less than 20% of the population managed to establish legislation which set the stage for systemic racial discrimination. In 1871, voting right was taken away from the Chinese and the First Nations. As anti-Chinese sentiment escalated, some Chinese started to migrate east. Most of the first Chinese residents in Ontario were those who had left British Columbia. There were a few in cities such as Toronto and Ottawa who had come from the United States where they were also discriminated against.

(This article was first published in the column “Home in a Distant Land” in Owen Sound Hub in April 2017. The column is one of the three components of A Chinese heritage project of the same name, which has been made possible by the Community Fund for Canada 150th, Community Foundation Grey Bruce, the Government of Canada and extraordinary leaders from coast to coast to coast. The other two components are a traveling exhibit which will be visiting 12 communities and the presentations in 15 elementary schools throughout Grey Bruce in 2017)

#Community Foundation Grey Bruce#Canada 150#Canadian Chinese#Chinese Canadian#Grey County Ontario#Bruce County Ontario#Grey Bruce#Home in a Distant Land#Owen Sound Hub

0 notes

Text

Home in a Distant Land

With the support from Grey Bruce Chinese Heritage & Culture Association and Grey Roots Museum & Archives, I have an opportunity to put my research data into good use. Home in a Distant Land is a project about Chinese heritage in Grey Bruce. It has two components - an exhibit which will travel to 12 communities, and presentations in grades 4 to 6 classrooms throughout the two Counties. The project is funded by the Community Foundation Grey Bruce’s Canada 150 matching grant.

#Chinese Canadian#Grey Bruce history#Grey Bruce Counties#Grey County#Bruce County#Chinese immigrants in Canada#Canada 150

0 notes

Link

Soon after moving northwest from Toronto to GreyBruce 22 years ago, I told my husband half-jokingly, “ I am going to try wonton soup at every Chinese restaurant between here (Sauble Beach) and Toronto, and create a website to write about it.” I did not drive at the time; and soon first son was born, then second, then six years later the third one” So, I did not visit many restaurants and the website was never built, although wonton soup is still my “must-have” item whenever we dine at a Chinese restaurant to these days.

In summer 2014, my husband and I took our children out west to Winnipeg to visit his family. I made of point of having as many of our meals at Chinese restaurants along the Trans-Canada Highway as possible, and talk to the owners whenever I could. I posted a video of all the restaurants I had visited.

It is wonderful to see that someone else has a similar idea!

0 notes

Photo

Another effort to bring lion dance to Grey Bruce Chinese New Year Celebration 2017

0 notes

Photo

First of three fundraising events at Grey Roots Museum & Archives. The goal is to bring dragon dance to GreyBruce Chinese New Year Celebration 2017!

0 notes

Text

A Fresh Start in a New Land

I began my research by looking up Chinese surnames on old phone and business directories. Lately, I was reading Lives of the Family, Stories of Fate & Circumstance by Denise Chong; in one of the short stories, the father changed the family name to Johnston in order not to stand out too much in a small town near Ottawa where he settled his family. I wonder if I have missed any Chinese residents in Grey Bruce in the past decade or so because I could not idnetify them on the directories.

0 notes

Text

Chinese in Owen Sound - Then and Now

youtube

Chinese people have been living in Owen Sound Ontario, Canada for over 100 years.

On February 21, I did a 10-minute presentation at Grey Roots Museum & Archives on Chinese in Owen Sound during our Grey Bruce Chinese New Year Celebration 2015. I gave an overview on two groups of Chinese residents: the early settlers who lived in Owen Sound between late 1800s and early 1900s, and the recent immigrants who arrived in the pass 30 years.

The earliest record of a Chinese person living in Owen Sound was in the 1896 Morrey's Directory. His name was Wing Lee. He was a laundry man from China. The 1901 Census shows that Wing's brother Hoy Lee and his cousins Wai Lee were working with him. The Census also records two other laundryman, Tin Wah and Jim Lee, and their assistants. That totals 10 Chinese residents in Owen Sound, all of whom men.

By 1924, Chinese population in Owen Sound has grown to about 25. A large percentage was still men, but some also had their wives and children here. All the Chinese residents were either running landries or restaurants, or working for one. They were all from mainland China, mainly the southern part by the sea.

These early settlers were men who came alone; some of them would later send for their sons who became old enough to work, the youngest age was 9. Few of them could afford to bring the wives over. Most of these men did not read, write or speak English, and some did not even read or write Chinese. They made a living doing strenuous, long hour labour work. They experienced discrimination on a daily basis, which could be quite hostile at times. Systemic discrimination stopped Chinese immigrants from coming to Canada when the Chinese Exclusion Law was introduced in 1923.

The demographics of the present Chinese population in Owen Sound are quite different from those of their counterpart. In the past 30 years, Chinese residents in Owen Sound have come from different parts of China, Vietnam, Hongkong, Singapore and Thailand. They came as families. There are also 2nd generation Chinese who were born in Canada.

Presently, there are about 80 Chinese living in Owen Sound. These recent immigrants read and write Chinese; a lot of them have high education and are skilled workers or professionals who speak, read and write English. Our occupations range from restaurant owners/workers, convenient store owners, skilled workers to professionals.

All in all, our experience of living in Grey County has been positive –- a lot of people take an interest in and appreciate Chinese culture. Although at times, we do experience mild forms of discrimination, which can probably be attributed to the stereotypical perception of Chinese.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Canadian Chinese Restaurants

When Chinese first arrived at Ontario over 100 years ago, they earned their living running either laundries or restaurants. While Chinese laundry has extinct quite a while ago, there are still Chinese restaurants all over Ontario. Walking into a Chinese restaurant in a small mining town in Ontario takes you back in time. The decor, the food, even the accents of the owners when they speak Catonese all seem so "old".

This summer, my husband and I went on a road trip to Winnipeg with our children. Along the way, I took pictures of Chinese restaurants in almost every town we stopped at, and ate in some of them. We even had Canadian Chinese food for both lunch(at Three Aces in Iron Bridge) and dinner(at Wok with Chow in Marathon) one day! Born and raise in Hongkong, I used to "chop suey" too "Canadian" for me. However, having the opportunity to speak with some of the restaurant owners and listen to their live stories, I have come to appreciate Canadian Chinese food:

120 years ago, Men laboured nights and days in Canada to feed their families back home in China, an ocean away. Most of them did not get to unite with their loved ones until they were old and fragile old men. Some of them did not even get to live that long. Today, men and wives come and start a new life together. Those move away from the city to rural Canada hope to not just make ends meet, but be able to give their children a better education. They leave their children with relatives in Toronto to attend schools and university. They provide for their children, visit them whenever they can, but don't get to watch them grow up. At least, the men don't have to wait for 40 years to be reunited with their wives and embrace their children.

0 notes

Video

youtube

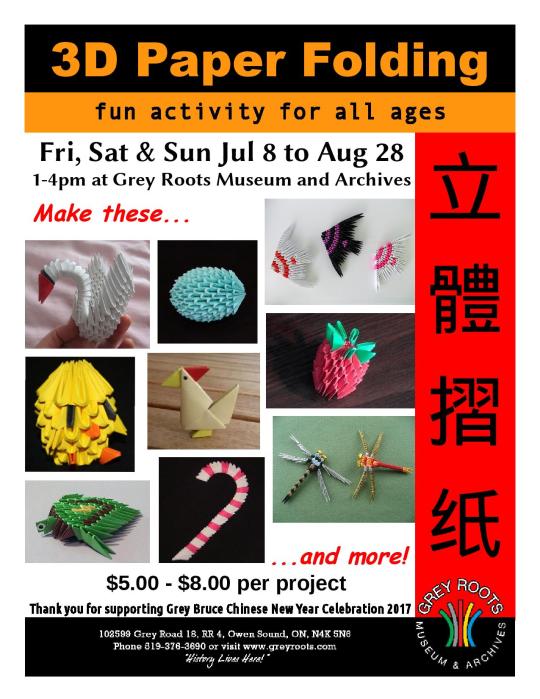

Paper folding has been a children activity in Chinese culture for a long time. My mother used to fold all sorts of things with me - boats, houses, pagodas...

0 notes

Video

youtube

Two weeks is not enough time to master a language. However, it was suffice for the students(8 to 14 years of age) to learn how to count up to 99 in Cantonese, do simple addition on the abacus, understand the basic structure of simple sentence and questions, and acquire a reasonable vocabulary for easy conversation in Cantonese.

#Chinese in Canada#Chinese in Owen Sound#chinese in ontario#chinese class#cantonese#chinese language

0 notes

Video

youtube

Over a decade, I have been working away silently in creating an environment which encourages my own children to learn about their Chinese heritage. This award pleases me not because my effort is recognized; but because it reflects that the community appreciates cultural diversity.

0 notes

Photo

Chinese Immersion Classroom at Grey Bruce One World Festival on May 23

0 notes