Photo

The Choucroute Route

By Andrew Sean Greer

Illustration by Luci Gutiérrez

Savuer || April 15, 2015 || May 2015 Magazine Issue

We were called les belles étrangers: the beautiful foreigners. Twelve American writers brought to France as part of a cultural exchange delivering foreign literature to rural communities. After we arrived in Paris, we were paired off and given our assignments: One set was sent to Corsica, another to Nice, another to Marseille. I was informed, however, that my partner had hurt his back. I would be traveling alone to…the director looked at his clipboard. “Mulhouse,” he said. Pronounced “mool-OOZE.” Somewhere in Alsace. I was introduced to my chaperone—a pretty English-free Algerian girl named Sylvie—and off we went to the German border, to Mulhouse, a wind-harried industrial town once known as the “Manchester of France.” There I was introduced to the Provincial Librarian, a weary, bald, monkish man. I say monkish because, though fluent in English, he seemed to have taken a vow of silence, and in this silence I was taken to dinner. Here, at last, I felt hope. One of my earliest childhood memories is of an Alsatian restaurant that served choucroute garnie, a rustic dish of sauerkraut, bacon, sausage, and potatoes. I ordered it in my halting French, but the Librarian, finally speaking, intervened. “No no,” he explained, “this is not the place for choucroute.” Obediently, I sat back. But I vowed I would have my choucroute.

Early the next morning, Sylvie appeared in my hotel lobby and led me to where the Librarian waited, in his car, a Twingo, to bring me to Pulversheim. The road was bumpy, the sky gray; we passed through small towns of half-timbered buildings and brick church towers. Then to the library, where a number of local coal miners had gathered to hear me read from my novel. Dinner was in the town’s sole restaurant. I looked at Sylvie and the Librarian and asked: “Choucroute?” They shook their heads: not the place for choucroute. The next day, I was taken via a winding road to a mountaintop in the Vosges where a blanket of fog erased a famous view. We stood beside the Twingo in silence as the wind whipped around us. Then down the mountain to Murbach, where we ate in the library itself, crammed into a kids-section table while a librarian unwrapped the cellophane from my slice of pâté. No choucroute. The next day, through roads so narrow the Provincial Librarian had to fold in the side mirrors, we arrived in medieval-looking Ensisheim. In a church shop I discovered an embroidered recipe for choucroute, with impossible ingredients like “lard du Strasbourg,” but alas, it was not for sale. After I had read to the coal miners there, the Provincial Librarian drove through the twilit forest to a crumbling monastery, where he stared longingly as though he belonged there; Sylvie had me take pictures of her in a new hat.

Guebwiller was next, in the pouring rain, and the Provincial Librarian drove so slowly that one motorcyclist after another passed us on the road. The librarians there were proud to show me “American desserts” they had made from online recipes; these turned out to be cupcakes. The next day, we reached Aspach-le-Bas through dark early-morning roads where the only lights in the towns we passed through were from bakers. I arrived in time to have a lunch of aspic and red wine with the high school principal. No choucroute. I read to miners in Ottmarsheim, Ungersheim, Houssen, Carspach, and Munchhouse. But it seemed that no place—not even hopeful-sounding Munchhouse—was the place for choucroute. When my time was finally over, and we drove south through the Pfaffenheim Forest back to Mulhouse, to a quaint little restaurant, I was once again defeated. I asked at last: “All right, so where is the place for choucroute?” The Librarian exchanged a baffled glance with Sylvie before telling me, as if it were too obvious to be uttered: “But of course, you have it at home!” I could have hit him with a sausage.

Except that he was right; it is best at home, I later learned. There is nothing quite like having guests arrive to a house perfumed with Riesling-simmered pork or sitting down to enjoy the tang of good mustard with pork-soaked sauerkraut, smoky bacon, and wursts at your own table. And you may, as I do, make a wall of sausages between the meats and potatoes, re-creating on a plate that German border, that map of Alsace, where I read to coal miners on one choucrouteless trip to rural France.

Afar

“The Choucroute Route.” Saveur Magazine. May 2015. Issue 174. Editor in Chief Adam Sachs. Publisher Kristin Cohen. Published by Bonnier Corporation. Winter Park, Florida. Page 24.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Recipe || Rigatoni Amatriciana

Created by chef Fabio Viviani of Siena Tavern in Chicago, this Amatriciana sauce is a classic of modern Roman cooking (though it most likely came from the town of Amatrice about 90 miles away). Typically, it's made with few ingredients: garlic, guanciale (cured pork jowl), cheese and tomato. This version doctors up jarred sauce to keep it quick and calls for easy-to-find pancetta in place of the guanciale. This tomato sauce is sometimes paired with bucatini; here, Fabio dresses up rigatoni with it.

Serves 8 || Total Time 45 minutes

Tips To make ahead: Refrigerate sauce (Steps 1-4) for up to 4 days.

Ingredients

6 plum tomatoes

2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil, divided

4 ounces pancetta, diced

1 small red onion, diced

2 serrano peppers, seeded and minced

1 cup dry white wine

2 cups prepared marinara sauce

½ teaspoon salt

½ teaspoon ground pepper

1 pound whole-wheat rigatoni pasta

¼ cup chopped fresh parsley

15 leaves fresh basil, torn

Grated or shredded Parmesan cheese (optional)

Instructions

1) Preheat oven to 450° F.

2) Toss tomatoes with oil on a large rimmed baking sheet. Roast the tomatoes, shaking the pan halfway through, until blistered, 15 to 17 minutes. When cool enough to handle, peel the tomatoes and chop coarsely.

3) Meanwhile, put a large pot of water on to boil.

4) Cook pancetta in a large nonstick skillet over medium heat, stirring frequently, until crisp, about 8 minutes. Pour off all but 1 tablespoon of the fat. Add onion and serranos to the pan, increase heat to medium-high and cook, stirring frequently, until softened, about 2 minutes. Add wine and cook until reduced by half, about 5 minutes. Add marinara sauce and the roasted tomatoes and bring to a boil. Adjust heat to maintain a simmer, cover and cook for 5 minutes. Season with salt and pepper. Remove from heat.

5) While the sauce simmers, cook pasta according to package directions. Drain and return to the pot. Add the sauce, parsley and basil; toss to coat. Serve with Parmesan, if desired.

Recipe by Fabio Viviani || Food Photography by Con Poulos

EatingWell || Source: EatingWell Magazine, September 2020

EatingWell Magazine. Sept 2020. Volume XIX, No 7. Editor in Chief Jessie Price. Publisher Tiffany Ehasz. Published by Meredith Corporation. Des Moines, Iowa. Page 79.

0 notes

Photo

Some of the World’s Rarest Wines Come From This Region in Europe

By Jason Wilson || Oct 25, 2016

Photos by Harry Mitchell

Afar || From the November/December 2016 issue

I sure as hell didn’t recognize them. Nicolas Gonin didn’t either, and “I’ve been looking for them for a long time,” he said with a smirk. We were gazing toward the ceiling of a 12th-century abbey in Saint-Chef, a medieval town in France’s Isère department, in the Alps east of Lyon. Most visitors to the abbey focus on its Romanesque mosaics, but we were looking at something else: a frieze above the altar that depicted grapes.

Even though I have been a specialist in obscure wine and spirits for many years, and Nicolas is a young winemaker of some renown, we had no answer for Jean-Luc Étiévent, the third member of our party, when he asked, “See the grapes and leaves? What is the variety? This is your first ampelographic question.”

We might call Étiévent and Gonin the Indiana Joneses of ampelography—the study, identification, and classification of grapevines. They are explorers on an obsessive hunt for the rarest wine grapes in the world. Étiévent is a cofounder of Paris-based Wine Mosaic, an organization that works to rescue indigenous wine grapes from extinction. All over the wider Mediterranean region, from Portugal to Lebanon, he and his similarly obsessed colleagues seek out growers of rare varieties, promote their wines, organize tastings, and connect them to each other, to wine importers, and to universities whose researchers can help them, essentially creating a support group for those who love obscure grapes.

I, someone who has been accused of being a wine geek, found myself in this abbey because Étiévent had invited me to join him on a trip to see—and taste—some of Wine Mosaic’s most successful projects. In the Alpine region where France, Switzerland, and Italy meet, isolated vineyards, strange microclimates, and relative obscurity—decades spent off the traditional wine world’s radar—have preserved local grapes and farming traditions. In just the past five years, Wine Mosaic has saved more than 20 traditional Alpine grape varieties from dying out, first by identifying them and then by working with farmers to sustain their small plots where the grapes grow.

For someone like me this is exciting news. Every grape that’s saved offers the chance to taste a new flavor. And I’m not alone. Recent years have seen a revived interest in little-known grapes from lesser-known regions. For instance, two decades ago, grapes like carménère from Chile, grüner veltliner from Austria, or assyrtiko from Greece were essentially unheard of in the United States. Now they’re quite familiar to wine drinkers. So the quest for even rarer grapes has intensified. While the new crop of sommeliers in big-city wine bars can be irritating, with their disdain for any wine that might be considered mainstream, we can thank them for creating a demand, however small and exclusive, for rare wines. Often, a sommelier’s love of obscure wines might seem like an embrace of obscurity for obscurity’s sake. But sometimes, it can serve a higher purpose.

It doesn’t take a wine geek to appreciate the biodiversity—and accompanying cultural diversity—these grapes represent. In a globalized world, it’s the local specialties we seek out. These grapes carry with them a sense of place. A taste of place. And it’s possible that in a few decades, if the world’s climate grows too hot, today’s famous wine regions might not be able to grow the grapes we currently love. Maybe the last place to produce great wine will be high in the mountains, and these unusual wines may be the only ones we drink.

We save these grapes, then, for the same reason we save heirloom tomatoes and apples and heritage cattle, and build vast seed banks. These organisms may hold clues to solving the challenges of climate and disease, as well as preserving the historical record of human taste.

Etiévents little quiz in the abbey was a trick question: The vines depicted in the frescoes have likely not been seen in this region for almost a century, perhaps longer. And though vineyards have surrounded Saint-Chef since at least 993 c.e., Étiévent said, “No one knows the wines from here anymore. Phylloxera destroyed everything.”

Phylloxera, the historic plague of sap-sucking insects that began in the late 19th century and ravaged a majority of vineyards across France and the rest of Europe, was probably the biggest reason that scores of local grape varieties began to disappear. When grapes were replanted, they were often the so-called “noble” types—chardonnay, sauvignon blanc, riesling, pinot noir, cabernet sauvignon, and merlot—chosen because they were easier to cultivate and sell. These grapes now grow everywhere from Napa to Australia to South Africa to New Jersey. In fact, 80 percent of the world’s wine is produced from only 20 kinds of grapes. Many of the other 1,348 currently known varieties face extinction.

After leaving the abbey, we visited Gonin’s simple tasting room in a basic yellow building near Saint-Chef. In 2003, Nicolas, who was then in his late 20s, took over land from his family, where his grandfather had farmed vegetables and tobacco alongside the vineyards. At first, Nicolas planted the usual suspects, chardonnay and pinot noir. “If I’d been more courageous, I would have put in more local grapes.” Over the last 13 years, he grew braver, planting traditional local grapes from the region: whites such as altesse and verdesse; reds such as persan and mondeuse. Now his wines appear on the lists of in-the-know sommeliers in cities like New York.

We tried Gonin’s 2014 verdesse, which is particularly rare. It tasted like snow from a mountain meadow that been melted in a hollow melon. Only around a dozen acres of the grape are grown in the world. (Cabernet sauvignon, by comparison, occupies more than 700,000 acres.) “This grape grows only in Isère, and we hope to keep it that way,” he said.

“So you don’t want to see verdesse grown in California?” I asked.

Gonin looked at me quizzically, like I was crazy. “No,” he said. For Gonin, indigenous grapes are inextricably tied to place and culture. California verdesse would be like Maine lobster from Kansas.

Later, we tasted his persan, Gonin’s most famous wine. In the 18th century, persan was considered one of the best red wines in France, but now there are only about 25 acres in existence. Gonin’s persan is very low alcohol, often under 11 percent, aged in steel or enamel tanks rather than oak barrels, and funky. It’s just the kind of wine the new generation of sommeliers promotes.

After our tasting, we visited a protégé of Gonin’s, a producer named Sébastien Bénard, who lives on a rustic farm near the French town of Moirans, just south of Saint-Chef. Bénard, 37, perfectly played the role of Young Hipster Farmer, with a scruffy beard and ripped shorts. Bees from his hives swarming his barn. After we drove to see his vineyard, framed by snowy mountains and the city of Grenoble in the next valley, we learned how Gonin’s mentorship had paid off: Bénard had discovered perhaps the only vineyard of an ancient grape called servanin. He had been working his own vines of persan near the plot of an 86-year-old man. Bénard noticed an odd leaf shape that made him realize what the man was growing. “Nicolas taught me how to identify the old grapes,” Bénard said. “I tried my best.”

“Last year, the man did all the work by himself, then he died two weeks before the harvest,” he said. Now, Bénard tends to the old man’s vines.

“Next year,” Gonin said, “Sébastien will make the only 100 percent servanin wine in the world.” Gonin beamed proudly at his protégé. “This is what we do,” he said. “I’ve visited 300 vineyards like this, looking for lost grapes. I spent four years studying and learning to recognize the grapes by the shape of the leaves.

“On a scale of 1 to 5,” I asked. “How rare is this vineyard?”

“Like a 6 or a 7.”

They were lucky to save the servanin. Just last year, they found a few rows of an extremely rare grape nearby, and they implored the farmer to keep them. When they returned the following harvest, the man had died and his heirs had sold the land to a developer. The grape was lost.

As the sun began to set over the mountains, we drove through rush hour traffic in Grenoble and northeast to the town of Bernin, to visit Domaine Finot, run by another young winemaker, Thomas Finot, who began growing local grapes here in 2007.

We strolled Finot’s vineyards, which sit at 1,500 feet and offer a view of Mont Blanc, then tasted his wines in the garage-like space that housed his tanks, barrels, and a “tasting room” section that resembled a frat house basement, with a dart board and an old yellow leather couch. But these were wines no frat party has ever served. In addition to verdesse and persan, there was a red called étraire de la Dhuy, of which there are fewer than 40 acres in the world. It tasted like eating a bowl of fresh cherries while smoking a clove cigarette and burning leaves in the yard. Then there was a white called jacquère, which was like a bright, tart lemon fetched from a stone cistern. “Oh, jacquère isn’t that rare,” Étiévent said. Rare, of course, is relative. There are only about 2,500 acres of jacquère in the world. You’re not going to be seeing bottles of it at your local supermarket anytime soon.

When some neighboring Isère winemakers arrived with their wines, our tasting at Domaine Finot turned into a party.

“Twenty years ago, people didn’t drink these wines,” said Laurent Fondimare, one winemaker who joined us. “All the old people here don’t like these local grapes. When we started, they said, ‘Ah these are ‘bad’ grapes.’ Now, they say, ‘Oh you make a good wine with bad grapes!’ This is a victory.”

By 11 o’clock the next morning we were tasting more esoteric wines. Inside the regional wine museum at Montmélian, a town about an hour’s drive from Moirans, we visited the Pierre Galet Center for Alpine Ampelography, named for a nonagenarian ampelographer who wrote the comprehensive dictionary of French grapes and whose life’s research resides in the library on the top floor. There, surrounded by the old books and files of Monsieur Galet (considered by many to be the father of modern ampelography) we tasted wines poured from bottles with white labels reading “Vinification Expérimentale.” The grape names were hand-scrawled on each label: salagnin (super purple and chalky), serenelle (super spicy and vegetal), and blanc de maurienne (super . . . just . . . well, weird; bitter almonds with hints of bong resin). Serenelle is so obscure that it’s not even listed in the current edition of Galet’s dictionary of grapes. In fact, only about 50 liters of each of these wines exist in the world. Tasting them was the wine equivalent of spotting a dodo or discovering a lost bronze age tribe.

I knew my father, a wine aficionado, would be awake this early in Florida, and so I texted him a photo of the empty glasses and the hand-written bottles. “Tough work,” he texted back. “Are the wines any good?”

I put my phone away. As fathers so often unwittingly do, he turned up the volume on doubts that had begun to whisper inside my head. All of the wine I had tasted on this journey had certainly been . . . interesting. Many of the wines had been very good, some amazing. But not all of them. And each time I tasted a rescued, indigenous grape that I didn’t enjoy, I felt guilty, as if my negative judgment might banish this grape forever. At the same time, another thought nagged at me: Was all this just a privileged exercise in geekiness and arcane trivia? I started to worry I was falling down the same rabbit hole as those hipper-than-thou sommeliers who sneer at people who order chardonnay. Was I, too, becoming a wine douchebag who loved obscurity simply for obscurity’s sake? Why get all Indiana-Jones’ed-up to save crazy, long-forgotten grapes? Isn’t wine confusing enough already?

A few nights later, at the 16th-century Château de Villa in Sierre—billed as Le Temple de la Raclette—the menu was straightforward: raclette. Here, in the Swiss canton of Valais, less than three hours’ drive from Isère, melted cheese is serious business. A racleur scraped hot, bubbling, gooey raclette from a wheel onto warm plates that were then whisked to our wooden table, where we added small boiled potatoes served from wooden baskets, along with cornichons, pickled onions, chanterelle mushrooms, and rye bread. And after that raclette, there was more raclette. When I asked for ice water, I was gently scolded by the waiter: “Don’t drink cold water with raclette. The cheese will congeal into a cheese baby in your stomach.”

As another round of raclette arrived, Étiévent poured a glass of humagne blanche, a white wine that tasted big and sexy, full of ripe exotic fruit, but surrounded by delicate floral aromas—sort of like mountain flowers picked by a Kardashian wearing a dirndl. The grape dates to at least the 14th century, and in the mid-19th century it was the most widespread grape in Valais. But now there are only about 75 acres of humagne blanc left in the world. Frankly, at this point in my travels, a glass of humagne blanc seemed as normal as one of chardonnay or cabernet sauvigno.

Our wine sherpa at the table was José Vouillamoz, a short bespectacled Swiss guy in his mid-40s who wears a flat cap and kicks around his hometown of Sion on a kid’s scooter—but who also happens to be a world-renowned geneticist and ampelographer and co-author of the encyclopedic tome Wine Grapes: A Complete Guide to 1,368 Vine Varieties, Including Their Origins and Flavours.

“We will now taste one of the rarest wines in the world,” said Vouillamoz with a flourish. He poured me a glass of himbertscha. In the entire world, there is only one vineyard of himbertscha, and it is less than two acres. From this, fewer than 800 bottles are made. Himbertscha is one of the strangest white wines I have ever tasted—like a forest floor of moss and dandelions that’s been spritzed with lemon and Nutella.

I began to see into the future after we drove from Montmélian to the Château de Miolans, a fortress that dates back more than a thousand years and sits in the mountains looking out at the Italian Alps. Château de Miolans was a prison in the 18th century, known as the “Bastille of the Alps,” whose most famous prisoner happened to be the Marquis de Sade.

It was a warm, sunny October day—definitely not the weather I expected in the Alps. Atop the fortress walls, we attended a tasting of wines by Les Pétavins, a group of a dozen local organic producers. Someone put out a plate of charcuterie and a cheese called persillé de Tignes, and we tasted lovely examples of such grapes as persan, altesse, verdesse, and jacquère along with a wine called Chignin-Bergeron, made of roussanne.

Our host was Michel Grisard, a tall, ruddy-faced winemaker with a huge smile, about my father’s age, whom everyone called “the Pope of Savoie.” Grisard had been traveling and tasting with us, and he’d seemed like a goofy troublemaker, always filling up glass after glass and rushing us on to the next obscure wine. Now it was his turn to share the wines under his label, Domaine Prieuré Saint Christophe—in particular the grape mondeuse noire, which he almost single-handedly saved from extinction in the 1980s. Tasting Grisard’s mondeuse noire was a revelation: floral, fruity, smoky, foresty, but so light and dangerously drinkable. Later at dinner, when we tasted older vintages of Grisard’s mondeuse, dating from the 1990s and 1980s, my appreciation only deepened. These were simply great wines.

It may have been because it wasn’t quite 1 p.m. and I’d already tasted more than two dozen wines, but looking out over the Combe de Savoie valley, on this unseasonably warm day, a wave of clarity washed over me. I had a vision of a world in which climate change has pushed winemaking up into the mountains and only the native grapes survive. A world in which people rhapsodize about mondeuse the same way they do about pinot noir today. If all those future wines taste as good as this, I’d be OK with it. And I would be deeply grateful for what these wine geeks had saved.

And if that isn’t what the future looks like? Well, a simple truth that Étiévent spoke the night before at dinner still resonated with me: “Drinking the same wines all the time is really boring.”

Afar

Wilson, Jason. “How Do You Like Your Wine? Rare and Well Done.” Afar Magazine. November/December 2016. Volume 8, No 6. Published by Afar Media. Editor in Chief Julia Cosgrove. Publisher Bryan Kinkade. San Francisco. Pages 120-122, 124,127-129.

0 notes

Photo

Recipe || Lemon-Caper Tuna Sandwich

This briny, tangy sandwich, from Joanne Chang of Flour Bakery + Café in Boston, benefits from sitting awhile after assembly. The oils from the tapenade will seep into the bread, making it moist but not soggy, and the sharp flavors of pickled fennel, capers, and olives will mellow pleasantly.

Serves: 2 Sandwiches

Total Time: 30 minutes

Ingredients

For the Pickled Fennel:

1⁄4 cup rice wine vinegar

3 tbsp. sugar

1 tsp. kosher salt

1 fennel bulb, trimmed and cut into 1⁄4″ pieces

For the Sandwich:

1⁄4 cup capers, drained and minced

6 tbsp. olive oil

2 tbsp. minced chives

1 1⁄2 tbsp. Dijon mustard

2 (4 oz.) cans tuna in water, drained

2 lemons, zested and juiced

2 sprigs rosemary, minced

Kosher salt and freshly ground black pepper, to taste

1⁄2 Whole-wheat baguette, halved lengthwise and then crosswise

Baby arugula, for serving

For the Olive tapenade:

1 cup pitted kalamata olives

2 tbsp. olive oil

1 1⁄2 tbsp. minced basil

1 tbsp. fresh lemon juice

1 tsp. capers

1 clove garlic

Kosher salt and freshly ground black pepper, to taste

Instructions

1) Make the pickled fennel : Combine vinegar, sugar, salt, and 1⁄2 cup water in a 1-qt. saucepan over high; cook until sugar has dissolved, 3 minutes. Pour over fennel; cool.

2) Made the tapenade : Combine olives, oil, basil, lemon juice, capers, garlic, salt, and pepper in the bowl of a food processor; blend until roughly chopped.

3) Make the sandwich : Stir 1⁄3 cup pickled fennel, the capers, oil, chives, mustard, tuna, lemon zest and juice, rosemary, salt, and pepper in a bowl. Spread tuna salad on bottom of baguette, then top with arugula, tapenade, and top of baguette.

Recipe By Joanne Chang. Photo by Joseph De Leo

Saveur || April 8, 2015

Saveur Magazine. May 2015. Issue 174. Editor in Chief Adam Sachs. Publisher Kristin Cohen. Published by Bonnier Corporation. Winter Park, Florida. Page 30.

0 notes

Photo

This Tiny Japanese Town Is the Origin of the “Superfood” Matcha

By Alex Schechter || Feb 11, 2016

Photos by Ko Sasaki

Afar || From the March/April 2016 issue

There is a small city in central Japan called Nishio. To get there by train, you take a scenic three-and-a-half-hour ride from Tokyo, past Mount Fuji and the rippling Pacific coastline. Nishio itself looks unremarkable: quiet residential blocks that could be found anywhere in Japan, a few restaurants, all surrounded by flat parcels of green farmland. But mention the city to tea aficionados and they will immediately respond: matcha!

As Maine is known for lobster and Kentucky for bourbon, the fields of Nishio are famed for growing a variety of Camellia sinensis, the mother plant from which most teas (green or black) are made. The leaves from this plant are eventually stone ground and turned into some of the world’s finest matcha, a bright-green, powdered tea.

What makes this brew so special? Perhaps it’s the taste: smooth, bracing, slightly bitter. Perhaps it’s the mystical, centuries-old ritual of pouring the ground tea into a heated cup, carefully adding hot water, and mixing them together with a small bamboo whisk until the liquid is light and frothy. Perhaps it’s the nutrients. Unlike other green teas, which are steeped, matcha is mixed directly into the water and fully ingested, which gives you a bigger boost of antioxidants, caffeine, and L-theanine, an amino acid that devotees say creates a super calm, focused mental state. In ancient Japan, people thought matcha had magical properties, and Samurai warriors drank it to stay alert during battle. Today, matcha can be found everywhere from high-end coffeehouses to roadside 7-Elevens. But matcha from Nishio or Uji, another tea-growing region near Kyoto, is still viewed as the crème de la crème. There, far from Japan’s megacities, the soil is rich and the water pristine, conditions that produce an intensely flavorful, nutrient-rich brew.

Matcha is also having a moment in the United States, thanks in large part to Graham and Max Fortgang, who in 2014 opened MatchaBar, the country’s first all-matcha café in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. The duo discovered the tea by chance when they were served shots of ceremonial-grade brew in an East Village tea shop. They immediately identified the tea’s simultaneously soothing and vitalizing effects as an appealing alternative to coffee.

The Fortgangs source their matcha exclusively from one place, a Nishio farm-slash-general store on an irregular-shaped piece of land that has been owned by the same family for five generations. Every year, the Fortgangs travel to Nishio to help with the spring harvest, a weeklong event that brings the entire town together. Kids take off school, the streets are strung with tiny white flags depicting green leaves and bamboo whisks, and practically everyone in town, from teens to 80-year-olds, helps pick tea.

“Our whole business is based around this one product,” explains Graham. “It’s important for us to be there with the farmers, picking alongside them.”

After the harvest, the leaves are steamed, air-dried inside giant netted chambers, chopped up into large pieces, de-stemmed, and sealed in airtight bags in a farmhouse not far from the fields. There, each batch of matcha is ground to order in a mill made from hand-hewn granite until it has a texture finer than baby powder.

During the Fortgangs’ last visit, following a 13-hour day of picking, a segment about MatchaBar aired on a major Japanese network, a big win for the brothers. Japanese tea drinkers find it funny that Americans are only now catching on to something they’ve known about for centuries. “So for the family that grows our matcha to see the café understood and accepted by Japanese culture,” Graham says, “that’s the ultimate validation.”

Afar

Schechter, Alex. “Matcha Maker.” Afar. March/April 2016. Volume 8, No 2. Published by Afar MEDIA. Publisher Bryan Kinkade. Editor in Chief Julia Cosgrove. San Francisco. Pages 53, 54, and 56.

0 notes

Photo

Recipe || RYE SANDWICH BREAD

This loaf has unbeatable texture, deep rye flavor, and versatility. It can be baked in a standard loaf pan, a Pullman pan, or hand-shaped into a rustic batard or boule. This kind of versatility makes a perfect starter loaf for the timid baker!

Makes 1 (9x5-inch) loaf

Ingredients

2¼ cups (281 grams) all-purpose flour

1 cup (102 grams) light rye flour

1 cup warm whole milk (85°F)

¼ cup unsulphered molasses

2 tablespoons (28 grams) unsalted butter, softened

1 tablespoon (9 grams) caraway seeds

2 teaspoons (6 grams) kosher salt

2 teaspoons (6 grams) active dry yeast

1 large egg

1 tablespoon water

Instructions

In the bowl of a stand mixer fitted with the dough hook attachment, combine all-purpose flour, rye flour, warm milk, molasses, butter, caraway seeds, salt, and yeast until moistened. Let stand for 20 minutes to let the rye absorb some liquid and begin to relax a bit. Knead for about 8 minutes in the mixer, or 12 minutes by hand. Spray a large bowl with cooking spray. Place dough in bowl, turning to grease top. Cover and let rise in a warm, draft-free place (75°F) until doubled in size, 1 to 2 hours.

Turn out risen dough onto a lightly floured surface, and deflate it to remove excess air. Pull the four corners of the dough into the center, and roll gently with palms to form a loaf. Spray a 9x5-inch loaf pan or Pullman pan with cooking spray. Place loaf in pan. Cover and let rise in a warm, draft-free place (75°F) until doubled in size, 1 to 1½ hours.

Preheat oven to 375°F. In a small bowl, whisk together egg and 1 tablespoon water. Brush over risen loaf, and sprinkle with more caraway seeds, if desired. Using a sharp knife or lame, make 4 large slashes across top of loaf. Bake until golden brown and an instant-read thermometer inserted in center registers 190°F, 35 to 40 minutes. Let cool in pan for 20 minutes. Remove from pan, and let cool completely on a wire rack.

Bake From Scratch || Aug 19, 2016

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Recipe || Peperonata

Recipe by Carolyn Malcoun || EatingWell

Photography by Con Poulos

Source: EatingWell Magazine, September 2020

Serves 12 || Total Time 1 hour 30 minutes

Serving Size: ½ cup

Sweet peppers are the name of the game here, but tossing a few hot ones into the mix would be nice as well. This recipe was developed to preserve the summer bounty from your garden or farmers' market; it freezes well for up to 3 months. Try this mélange of peppers, tomatoes and onions with a plate of cheese and crackers; toss it with pasta and chopped herbs; or pile it on grilled chicken and melt some fontina on top.

Tips: To make ahead: Refrigerate for up to 1 week or freeze for up to 3 months.

Ingredients

½ cup thinly sliced garlic

½ cup extra-virgin olive oil

1 tablespoon chopped fresh herbs, such as rosemary, thyme and/or oregano

1 large sweet onion, sliced

4 cups chopped tomatoes

3 ½ pounds bell peppers, sliced 3/4 inch thick

1 teaspoon salt

1 tablespoon white-wine vinegar

Instructions

1) Heat garlic, oil and herbs in a large pot over medium heat until fragrant and starting to sizzle, about 2 minutes. Add onion and cook, stirring occasionally, until softened but not browned, about 8 minutes. Add tomatoes and cook, stirring occasionally, until they are broken down, about 5 minutes. Add bell peppers and salt; bring to a simmer. Cover and cook, stirring occasionally, until the peppers are mostly submerged in the liquid they give off, about 40 minutes. Uncover and cook until the liquid is reduced by about half and the peppers are very tender, about 30 minutes. Stir in vinegar. Serve warm or at room temperature. Let cool completely before refrigerating for up to 1 week or freezing for up to 3 months.

EatingWell

EatingWell Magazine. Sept 2020. Volume XIX, No 7. Editor in Chief Jessie Price. Publisher Tiffany Ehasz. Published by Meredith Corporation. Des Moines, Iowa. Page 95.

0 notes

Photo

WILLIAM WERNER’S SECRET TO PERFECT CARAMELS

By Jennifer V. Cole || Oct 10, 2016

Photos courtesy Elle Wildhagen

William Werner, the sugar genius behind San Francisco’s Craftsman and Wolves, dishes on the secret to perfect caramels.

Why is caramel so magical?

Caramel is the sweet world’s beurre blanc. There’s a mystery around it.

What is the biggest challenge for a home cook?

Fear. Fear of burning the caramel or themselves. That’s what I hear nine times out of ten when I do a cooking demo or a class. But it’s not a terribly involved process. I think we sometimes overcomplicate it.

What’s the most important part of the process?

As with all confections, it’s about temperature. For my caramels, that’s 118 degrees Celsius. I cook it at a medium-high heat with a rapid boil. Bring it to a boil quickly and keep it there until you hit the temperature mark. If you slowly bring it to a boil, you’ve lost all of the momentum and reach that degree mark at a slower rate, and your caramel won’t work. Like with making jam, you want to cook it fast and get it done to get more flavor and texture. Once you’ve hit your temperature mark, add cold butter to stop the cooking. It won’t cool the caramel down, but it will stop the carryover heat and keep it from continuing to cook.

How do you monitor the temperature?

We use a really expensive digital probe thermometer from Ebro. It’s an investment, but it will last forever and is insanely accurate. But ThermoWorks makes some good thermometers with long lead lines and probes with alarms. You can set it to go off when the temperature is 117 degrees Celsius so you’re right there when it hits 118. If you’re going digital, don’t use the hand-held thermometers like you’d use with a pork roast. You want some distance between you and the boiling caramel like you get with a long lead device. Or, you should wear some really heavy gloves. You don’t want molten caramel on your hands.

Do you need a digital thermometer?

You don’t need anything fancy. What’s good are those classic candy thermometers that you actually stick in the pot that have mercury. Those are really accurate. Temperature is so important here—accuracy really matters. You just have to pay attention. This is not the time to go put clothes in the dryer or feed the dog.

What texture are you looking for?

For my candies, I go for a soft caramel stage. The caramel should be al dente. You should be able to bite into it and leave a mark from your teeth. You want it to have some chew and be tender, but not stick to your teeth. It should melt on your tongue, but not be a gloppy mess.

Is there a common mistake most home cooks make?

Adding cold cream to the caramel and making a hot mess. No matter what kind of caramel you are making, if you deglaze with cream or any other liquid, that liquid should always be hot. Not boiling. But it should be too hot to comfortably touch when you put your finger in it. If you add cold cream to your caramel mixture, it will go bananas and you’ll have a volcanic mess, and it won’t set in a pan.

You’re known for interesting flavor combinations. What’s your favorite?

Hands down it’s our chocolate caramel. The sugar is deeply caramelized, we emulsify with dark chocolate, and add big chunks of salt crystals. And we add in white shoyu, a white soy sauce with light floral notes that gives it rich salinity, like an umami Tootsie Roll.

Bake From Scratch

1 note

·

View note

Text

Pickles at Home

By Ali Francis

Bon Appetit | Sept 10, 2020

Without fail I turn to pickles to fill the sour gherkin-shaped hole in my half-Polish heart. I simply can’t imagine my days (read: grain bowls, chicken sandos, and lazy egg dinners) without those li’l puckers.

I’m not alone: In 2019, 241.44 million Americans—about 68% of y’all (not me, I’m from Down Under!)—partook in some kind of pickle consumption. (That figure does not include pickle-flavored chips, freezer pops, or, perplexingly, candy canes, which, if included in the count, might actually break the datasphere.) I feel comfortable calling it: We’re at *peak pickle.* So why the pickle mania? For one they’ve been a popular staple around the world for, like, ever (more on that in a bit). Second, you can pickle basically anything (Grapes! Onions! Beets!). And finally, they’re increasingly regarded as a standalone snack, not just your burger’s sidekick.

So, where did pickles come from? Why were they invented? And how can you make and use them to their fullest?

Stocking up for ye olde winter style of pickles has supposedly been around for over 4,000 years, according to, well, the internet (which has been around for about 30). In Mesopotamian times, pickles were born out of necessity and made for millennia after by fermenting fruits and vegetables in a salty liquid for long enough that they wouldn’t spoil on, say, a long voyage at sea. Fast-forward a few thousand years and you’ll see that most cultures have their own unique pickling method. In Iran, you might find your soup studded with ghooreh, which are sour pickled grapes. Petits cornichons are regulars on Parisian charcuterie plates. And Indian stews are often served with a side of oil-pickled mango or lime.

There are truly so. Many. Ways. To. Pickle! What we’re focusing on today, though, are quick pickles—a modern iteration that are less time-consuming than those long-haul ferments, don’t require canning, can be made with pretty much any fruit or vegetable, and can be customized to your liking. So now for the fun part: how to make pickles at home.

Sorry, what is a quick pickle?

Basically, any kind of fruit or vegetable that’s been chilling (literally, in the fridge) in vinegar, water, salt, (usually) sugar, and some mix of aromatics. Unlike Brad Leone’s half-sours, quick pickles aren’t fermented, so they don’t develop quite the same funky flavor. But they’re faster to make, requiring only a day or so hanging out in their bath before they’re ready to snack on. Quick pickles are also not shelf stable, meaning they need to be stored in the fridge, not on your bedside table. (For that, you would need to can them as you would jam. Which is a whole other thing.)

So, what’s the process for making quick pickles?

Simply put, vegetables are prepped, put in clean jars, covered in a salty-vinegary brine, and left to soak in the fridge. Here’s the scoop:

Step 1: Wash the jars

Clean vessels are key. Wash your jars, lids, and sealing rings with warm soapy water and rinse well. (Nobody likes a sudsy pickle.) Also, take into account the size of your jar: Everything needs to fit snugly inside your vessel.

Step 2: Prep the veg

There’s no rule against pickling produce whole, but your veg will absorb the brine faster if cut into pieces. Radishes are great in medallions, carrots are best as matchsticks or coins, onions should be sliced (not diced), and green beans need to be topped and tailed—same for cukes, which should also be quartered lengthwise. But before you do all this, you should consider how you want to use the pickles. If you’re making salad, you’ll want to thinly slice those veggies and pickle them raw. If you’re doing a straight-up crudités plate, you may want to boil them a little first, so they’re not too crunchy. Then, once you’re done prepping, transfer your haul into those clean (dry!) jars.

Step 3: Make the brine

A good brine has the proper ratio of vinegar, salt, sugar, and water with aromatics added to taste—more on this below! Use this BA-endorsed formula as a brine base for pretty much everything: Bring 1 cup distilled white vinegar, 2 Tbsp. kosher salt, 2 tsp. sugar, up to 2 Tbsp. spices (e.g., peppercorns, coriander seeds, and/or mustard seeds), and 2 cups water to a boil in a saucepan. (Editor’s note: You don’t HAVE to heat your mixture if you need some extra-quick 10-minute pickles, but in that case follow these steps and omit the water altogether.) Stir until the mixture is dissolved and remove from heat.

Step 4: Chill your pickles

Once the brine is hot and ready, pour it into your jars—leaving ½ inch of headspace between the liquid and the rim for liquid-induced expansion—and screw on the lids. The heat will soften your veg a little and speed up the pickling process. Let the jars cool to room temperature, then transfer them to the fridge. Do your best to wait 48 hours for the ultimate vinegary snap.

Which are the best for pickling?

Beyond the classic cukes, there aren’t many fruits or vegetables that wouldn’t taste great pickled. Ramps? Check. Bean sprouts? Check. Summer corn, watermelon rinds, turnips? Check, check, check! The list truly goes on and on. That being said, there are a few good guidelines to follow when picking produce:

Fresh is always best. Choose vegetables that are naturally firm. This is a good sign they’re fresh—as vegetables age, they lose water and become softer—and will stay crisp while they’re brining.

Trim those stems and ends. The enzymes in both can lead to mushy pickles. Science!

Stock up at the farmers market, if you can. Conventionally grown fruits and veggies are often coated in a nasty wax. On that note wash your produce before using it, no matter where you got it.

Still have your heart set on cukes? Fine, here’s what you need to know.

How should I flavor my pickles?

There are about as many ways to zhuzh your pickles as there are vegetables to pickle. The secret to a truly memorable brine is in the aromatics—that mix of herbs (dill, thyme, oregano, or rosemary), spices (mustard seeds, coriander, peppercorns, red pepper flakes, or turmeric), and/or alliums (garlic, shallots, leeks, or scallions) you choose to add. Here are some of our favorite combos:

Chile + jalapeño + cilantro + black pepper

Coriander seeds + Thai chiles

Yellow mustard seeds + crushed red pepper flakes + bay leaf

Garlic + tarragon + black peppercorns

Sichuan peppercorns + star anise + red pepper flakes

What vinegars are the best to use?

Pretty much any basic vinegar is fair game when pickling, but whatever you choose is going to come through in your finished pickles—in a big way. So, make sure you like the flavor before dousing your vegetables. Distilled white vinegar, apple cider vinegar, rice wine vinegar, and white wine vinegar all work well and can be used in combination or solo. Red wine vinegar is great too, but beware: It will color most veg it comes in contact with.

How long will my pickles last?

Up to two months in the fridge. Which, let’s be honest, shouldn’t be an issue. For shelf-stable pickles that last eons, see this primer on canning and follow suit.

Is there anything I should avoid?

Listen, maybe you’re naturally a pickle pro the first time around. Or maybe you’ll find yourself in a pickle. To avoid these common pickling mistakes, heed this advice:

Your brine should lean salty, not syrupy. Be wary of recipes that call for more than a ¼ cup of sugar. It’ll be too saccharine.

Never skip the water. Unless you’re making ultra-quick pickles, the kind that sit in brine for about 10 minutes, you gotta dilute that vinegar with water.

Don’t ballpark your brine. There’s nothing worse than chopping the veg, boiling the brine, and then realizing that you don’t have enough liquid to fill your jars. Pro tip: Fill your vessel (with prepped veg inside) with water first, then measure it out with a liquid measuring cup so you know how much brine to prep.

Relax, green garlic is totally normal! Garlic contains an enzyme that causes it to turn shades of green or turquoise when it comes into contact with acidic ingredients. It’s totally edible. And totally FUN!

Bon Appetit

Photographs by Eva Kolenko.

Bon Appetit Magazine. Aug 2015. Volume 60, No 8. Editor in Chief Adam Rapaport. Publisher Pamela Drucker Mann. Published by Conde Nast. Page 88, 89.

0 notes

Photo

A Night Out in Rio Begins (and Ends) at This Bar

By Chaney Kwak

Photos by Ériver Hijano

Afar || Jun 2, 2016 || From the July/August 2016 issue

“Amigo!” Antonio calls out to a harried waiter trotting by us outside Pavão Azul, a tiny bar two blocks from Copacabana Beach. The waiter, carting plates heaped with Brazilian bar snacks, doesn’t stop. Antonio, my carioca (Rio local) drinking guide, and I are just two of many revelers vying for his attention.

One of the first things you learn about a pé-sujo, the Brazilian equivalent of a dive bar, is that catching the attention of a waiter is a sport unto itself. When “amigo” doesn’t work, you can shift gears to moço (young man), upgrade to chefe (chief), flatter with capitão (captain), or crank it up all the way to faraó (pharaoh) until one of the men jots down your order. Persistence pays off. Our waiter finally stops, scribbles chopp and frango à passarinho, and soon returns with two ice-cold draft beers and a platter of chicken morsels that have been marinated in lime, then fried and topped with slivers of garlic. They’re salty, oily, and zesty—just what you want on a languid afternoon.

I first fell in love with Pavão Azul seven years ago when I met Antonio, an acquaintance of an acquaintance who introduced me to the pé-sujo. By the end of the night, he was a true friend and Pavão Azul was on my all-time favorite list—despite the absence of the expected accoutrements. The bar, like most pé-sujos, has no real facade. Once the servers roll up the doors, the white-tiled space simply becomes part of the sidewalk, and its size requires you to get friendly with your neighbors—fast. The few tables are plastic, and the food and drink are classic: salt cod fritters, the rustic black bean stew feijoada (Brazil’s national dish), beer, and caipirinhas (the national drink).

But that’s the charm of the pé-sujo. More than the $1,000-plus box seats at the glitzy Sambadrome or the overburdened bleachers of the Maracanã soccer stadium, a sidewalk table gives you front-row access to Rio’s ever-changing spectacles: the sudden combustion of a marching band, a drag queen strolling by, or a parade of Ipanema girls who are, as the song goes, tall and tan.

The century-long history of the pé-sujo isn’t entirely clear. One theory speculates that its name, literally “dirty foot,” comes from the old practice of sprinkling sawdust under the tables, while others figure that the name owes to the regulars of yore, who were slaves without shoes. Today, following the salty scent of the pé-sujo will take you all around the city and allow you to sit elbow to elbow with cariocas from all walks of life. Menus vary little from place to place; the dependability is part of the homey comfort. You’ll always find teardrop-shaped coxinhas, whose crunchy savory shell gives way to tender, shredded chicken meat. Deep-fried cod balls are a reminder of Brazil’s maritime Portuguese heritage. And pastéis, half-moons of fried dough, are filled with such beloved ingredients as hearts of palm and salted beef.

That’s not to say that all pé-sujos are the same. In bourgeois Santa Teresa, locals, expats, and travelers mingle at the roomy Bar do Gomez. The nearly century-old institution began as a Spanish grocery, thus the faded tins of olives and aged bottles of cachaça crammed onto the wooden shelves. Bar Urca, near Sugarloaf Mountain, is best for people-watching and empadas, mini pot pies filled with beef jerky, bay shrimp, or crab meat.

Years after my first visit, Pavão Azul remains my favorite. I always encounter characters here: a local professor who spoon-fed me feijoada; a Brazilian architect eager to mark every art deco monument on my map; even a collagen-enhanced society lady who invited me back to her mansion. The bar is so popular that its owners, sisters Vera and Bete Alfonso, opened an equally no-frills branch across the street in 2011. Once, over batida, a cocktail of cachaça and coconut milk, Bete shared their secret to success: “We’ll never change.”

This article originally appeared online in June 2016; it was updated in January 2018 to include current information.

Afar

Kwak, Chaney. “Bite by (Brazilian) Bite.” Afar Magazine. July/August 2016. Volume 8, No 4. Published by Afar Media. Editor in Chief Julia Cosgrove. Publisher Bryan Kinkade. San Francisco. Pages 41-42, 44.

0 notes

Text

Recipe || Stewed Lima Beans

Recipe by Marble Owens Clarke

Photo by Johnny Autry

Serves 10

Total Time 1 hour 45 minutes

This lima bean recipe is the creation of Mable Clarke, a South Carolina cook and activist. This side dish is on the menu for Clarke's monthly fish fry that she started to save the Soapstone Baptist Church. No need for ham hocks with this recipe--her onion-rich roast turkey stock gives these humble beans a rich, savory flavor, but store-bought will also do the trick. A long, slow simmer coaxes the creaminess out of the limas.

Tips

To make ahead: Refrigerate for up to 2 days.

Ingredients

▪ 1 pound dried lima beans, soaked overnight

▪ 1 medium onion, coarsely chopped

▪ 8 cups low-sodium chicken broth or turkey broth

▪ 2 cloves garlic, crushed

▪ 1 ¼ teaspoons salt

▪ ½ teaspoon ground pepper

▪ ½ teaspoon ground cumin

▪ ½ teaspoon crushed red pepper

Instructions

1) Drain and rinse beans. Transfer to a large pot and add onion, broth, garlic, salt, pepper, cumin and crushed red pepper. Bring to a boil.

2) Reduce heat to maintain a simmer. Cover and cook until the beans are tender, 1½ to 2 hours. Serve the beans with the broth.

EatingWell

EatingWell Magazine. Sept 2020. Volume XIX, No 7. Editor in Chief Jessie Price. Publisher Tiffany Ehasz. Published by Meredith Corporation. Des Moines, Iowa. Page 90.

0 notes

Text

The Road to Abruzzo

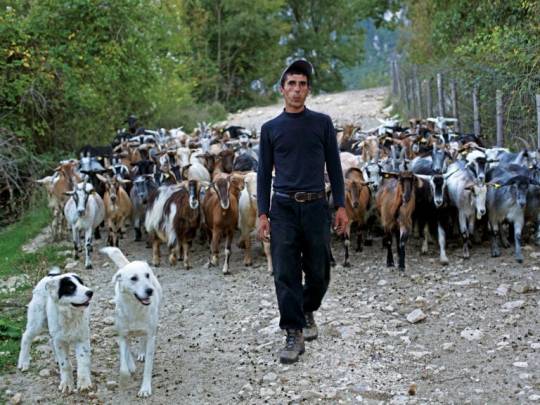

[Shepherding in Abruzzo. Abruzzo, once known for its wool, now produces extraordinary goat's and sheep's milk cheeses.]

By Adam Leith Gollner

Photos by Michael James O'Brien

Saveur | April 14, 2015

Every so often, a car cautiously serpentines down the winding hillside road away from the ancient hamlet of Ofena, in Italy’s Abruzzo region. It’s not the sort of drive you rush: Every downward curve opens onto yet another vista of superabundant grandeur. The views here in the Gran Sasso e Monti della Laga National Park are of such unrelenting picturesqueness it seems only right that the roadside benches are turned away from the landscape, toward Ofena’s unprepossessing buildings. The locals sitting there appear relieved to be resting their eyes from the ceaselessly breathtaking Apennine postcard unfurling behind them.

For at least a thousand years, the local tradition of transumanza—the seasonal movement of flocks of sheep and goats from mountains to grazing pastures and back again—has been practiced up and down these rocky slopes. “Abruzzo is transumanza,” baron Luigi Cataldi Madonna tells me, when I meet him at his winery in the valley beneath Ofena. “It’s the soul of Abruzzo. Everything comes back to the transumanza: the food we eat, the wine we drink, the lives we lead.”

[Abruzzo L’Aquila Ofena]

Cataldi Madonna is a legendary figure in these parts. A winemaker, a professor of philosophy at the Università dell’Aquila, and a passionate history buff, he makes sure to point out that the road that brought me here is very much like the pathways that shepherds have walked for centuries. Winemaking is the other ancient tradition. Here, in the amphitheater-like valley known as “the oven of Abruzzo,” air from the Adriatic Sea blows in over the hills, bringing with it a coating of salinity that seems to impregnate Cataldi Madonna’s grapes with oceanic freshness.

Cataldi Madonna is largely responsible for rescuing a previously unheralded grape variety called pecorino that is now in vogue across Italy. (The name derives from the Italian word for “sheep,” a nod to the shepherds—and their flocks—who ate the grapes while traveling through the region.) His bright, lemony wines are ideal with food, as I learn when he brings out some pasta cresciuta—puffy disks of fried pizza dough—as well as platters of cheese, homemade cold cuts, offal sausages, salads, and olives. I make an aside about this being a panarda, a traditional feast in the region, but Cataldi Madonna waves off my suggestion.

“The panarda is not just a meal,” he says, “it’s a celebration. It starts early in the evening and finishes the morning after. There are dozens of dishes—always an odd number, that’s very important.” According to Cataldi Madonna, soups, lamb dishes, ravioli, and a ton of fava beans are integral to the feast, which honors St. Anthony, the patron saint of farmers and shepherds. “The panarda is a ritual of excess here in the countryside,” he says. “And the dishes of the panarda are all dependent on the transumanza.”

This place is defined by a still-evident link to the tradition of moving around to find and grow food. The sheep move to eat. The people of Abruzzo eat to celebrate. And I, a visitor in a rental car, plan to drive up and down these hills and honor the precedent they set.

Nobody I knew had ever been to Abruzzo before. When I told Roman friends where I was headed, they said things like, “That’s the deep, deep countryside.” They couldn’t understand the appeal, which seemed surprising, given its proximity to Rome (L’Aquila, the capital, is an hour and a half away by car) and the fact that many Roman recipes, starting with spaghetti alla carbonara and bucatini all’amatriciana, are purportedly from Abruzzo. The existence of a still-hidden region in such an overrun corner of the world clearly merited deeper investigation.

Leaving Rome, my rental car bobbed its way through a sea of Fiats and Alfa Romeos, but after a while I bore right onto the A24 and all the other cars stayed to the left. I breezed along with barely anyone else on the road, past medieval castles perched on rocky hillsides, undulating valleys rolling out to infinity, and Himalayan-high mountains with snowy shoulders.

[Spaghetti alla Chitarra with Lamb and Sweet Pepper Ragu. Lighter than the rich beef and pork ragùs of other Italian regions, this Abruzzo specialty features bell peppers mixed into the sauce and cooked briefly so they retain their shape and lend a pop of sweetness. It is typically served over spaghetti alla chitarra (pasta from Abruzzo that is shaped on a tool that resembles a guitar), though it makes a delicious sauce for almost any type of long noodle.]

When I arrive in the port of Pescara, a bustling urban center on the Adriatic’s golden coast, my first stop is Taverna 58, a bastion of traditional Abruzzan cooking. The owner is a dapper, white-haired gentleman named Giovanni Marrone, who greets customers with a friendly, reserved demeanor. He assures me that the best way to sample various facets of la tradizione is by getting a tasting menu. He starts by sending out arrosticini, a local specialty of flame-grilled mutton skewers, followed by charcuteries and terrines, all of which pair splendidly with a Montepulciano d’Abruzzo by the legendary winemaker Emidio Pepe. Older vintages of Pepe’s wines are the ones more likely to make their way to the U.S., fetching hundreds of dollars per bottle, but one of the joys of coming to Italy is that Pepe sells young vintages of his earthy, bold, untamed wine in abundance here, and at much lower prices.

With the stage set, the main course arrives, Taverna 58’s chicken “in porchetta style.” The recipe begins with chicken marinated in olive oil, honey, fresh rosemary, salt, and white wine. When it’s ready, the chef ties it up like a porchetta, using raffia to wrap it around bamboo rods, and grills it. As good as it is, juicy with crackling skin, the pièce de résistance for me comes at the end of the meal, when Marrone wheels a cart to the table and whips up some fresh zabaglione with marsala—”con grande passione,” as he puts it.

The next day, crossing more regi tratturi (centuries-old transumanza pathways), I drive southwest to meet Nunzio Marcelli, president of the Abruzzo Shepherds Association. I’ve never met a shepherd before, let alone an alpha shepherd president. I suppose I’d been visualizing a man leaning on a wizened hazelnut crook wearing a long gray cloak, but when Marcelli comes out to greet me, he strolls over in a simple polo shirt and jeans. Even shepherds have Casual Fridays, it seems—although Marcelli assures me that many traditions remain intact here. “Just wait until you try our cheeses,” says Marcelli, a bearded, tanned, potato-fingered outdoorsman.

After we amble around his rustic agriturismo—filled with sheep, goats, chickens, dogs, and children—we join a colleague of Marcelli’s bringing a herd of goats down the hill. The shepherd’s job is to keep his flocks healthy and protect them from predators (these woods are still home to bears, wolves, and wild boars). Historically, the region was known for wool, but today, sheep and goats are mainly used for culinary purposes, as I learn over dinner with Marcelli and his family. We try juniper-smoked ricottas, goat yogurt pecorinos, and award-winning caciocavallos made with pezzata rossa cow’s milk. Marcelli’s daughter Viola prepares homemade gnocchi in a saffron-ricotta sauce, and we end with a local gentian root digestivo and Aurum, an orange liqueur produced in Pescara since 1925.

Dinner confirms something I’ve sensed while traveling throughout Abruzzo. Since so many people harvest their own fruit here and folks like Marcelli age their own cheeses, grow their own vegetables, and make their own pastas and olive oils, I realize that if some form of global economic meltdown were to come, not only would Abruzzans be fine, but life would continue pretty much just as it is.

I forge onward, into the Apennine mountains and over to Vasto, the birthplace of brodetto alla vastese, a celebrated local fish soup that is bursting with Mediterranean seafood and shellfish. A trip up the golden coast is one of the most beautiful drives in all of Italy, especially if it ends at the Emidio Pepe winery.

I arrive in the middle of harvest time, so Pepe himself brings me straight to the vineyards, where his workers are picking dazzling gold bunches of ripe trebbiano grapes. Now 82 years old, Pepe is a chiseled, strong-backed, handsome man who radiates calm and focus. He is famously quiet, but his pretty 22-year-old granddaughter, Chiara, couldn’t be more outgoing, and she shows me around as Emidio busies himself in the field.

“We have a lot of biodiversity here,” Chiara says, pointing out the sunflower plantings and fruit trees surrounding us. She draws my attention to the little clumps of wild herbs growing at our feet: parsley, mint, thyme. “We didn’t plant these,” she clarifies. “They just showed up here. We often find ‘spontaneous vegetables’ growing in the vineyard, things like swiss chard and fennel.” As she speaks, happy little lizards scamper around in the vines and butterflies flit through the honeyed light. Being there immediately makes me understand the slogan on the back of their family’s wine bottles: “Con il vino PEPE, hai la ‘VITA’ dentro.” It means: “A wine by PEPE has LIFE inside of it.” How could their bottles not be full of life when their vineyard feels like a nature preserve?

“These vines are full of fireflies in the evening,” Chiara tells me. “That’s significant because fireflies are delicate—they avoid anything that has been sprayed with chemicals. We respect nature here.”

For dinner, Emidio’s wife, Rosa, prepares a number of family specialties. She starts with a tray of grape-studded focaccia; then comes a dish of fried olives (oliva all’ascolana) stuffed with ground beef and pork. “My grandmother says this is one of the three recipes I will need to learn how to make or else I will never get married,” Chiara mentions.

Next I sample a classic timbale, in which layers of flat pasta sheets are quickly boiled, then covered with a veal-spinach mixture and tomato sauce with mozzarella, and then stacked. The lasagna-like dish pairs sensationally with Emidio’s cerasuolo, as well as with a plate of Rosa’s verdure con fagioli, freshly picked borlotti beans with Swiss chard from the garden. The final recipe in the matrimonial trinity is a venerable classic called mazzarelle: it’s like dolmas filled with lamb’s liver, heart, and lung. Rosa braises them for a few hours in white wine, to an entirely alchemical result.

As we eat, we try some of Emidio’s older vintages. His 2001 is leathery, spicy, full of vitality. “This wine is at the service of conquering eternity,” Emidio declares, taking a sip. Then we have the 1983. When he vinified it, Emidio considered it such a terrible vintage that he didn’t sell it. Yet today, 32 years later, it has blossomed. “The horse that is hard to break wins the race,” Emidio says of the bottle.

Around the dining room table are three generations of Pepes, from kids to grandparents. Someone runs into the kitchen singing “That’s Amore” (really). At times the conversation breaks into passionate fireworks, with everyone hollering about the economy, or politics, or the proper way of preparing a certain dish. Rosa keeps looking over at me and telling me that I haven’t eaten enough, even though I certainly have.

I say goodnight to the Pepes and head to my room at their agriturismo. Before going to bed, I open my window and look out into the night, filling my lungs with the purity of it all. The temperature has dropped but the crickets are still chirping away. Pulsing lights in the distance catch my eye. It takes me a moment to figure out what they are, but then I see—the vineyard is full of fireflies, twinkling away faintly, like stars.

Saveur

"The Road to Abruzzo." Saveur Magazine. May 2015. Issue 174. Editor in Chief Adam Sachs. Publisher Kristin Cohen. Published by Bonnier Corporation. Winter Park, Florida. Pages 48-57.

0 notes

Photo

Recipe || BRIOCHE AU CHOCOLAT LOAF

Adding dark chocolate to basic brioche gives it a rich, deeply satisfying twist that feels just as at home on the breakfast table as the dessert plate.

Makes 1 (9x5-inch) loaf

Ingredients

Basic Brioche Dough

¾ cup (128 grams) high-quality 64% dark chocolate, chopped

Egg wash

Instructions

Spray a 9x5-inch loaf pan with baking spray with flour.

On a lightly floured surface, turn out dough. Punch down dough, and sprinkle chocolate onto dough. Knead chocolate into dough briefly, just until chocolate is incorporated. Shape dough into a loaf, and place seam side down in prepared pan. Cover and let rise in a warm, draft-free place (75°F) until dough is puffed, 30 to 40 minutes.

Preheat oven to 400°F.

Brush risen loaf with egg wash, and bake for 15 minutes. Reduce oven temperature to 350°F, and continue baking until golden brown and a thermometer inserted in center registers 190°F, 35 to 40 minutes more.

Bake From Scratch || Sept 12, 2016

0 notes

Photo

Recipe || BASIC BRIOCHE DOUGH

At its heart, brioche is the gorgeous love child of a pastry chef and a bread baker. Think of it as part bread-part cake that combines the backbone of a dessert maven’s repertoire (milk, eggs, sugar, and butter) with the rich yeast of the boulangerie.

Makes 12 Mini Brioche à Tête, 1 large Brioche à Tête, 1 Bubble-Top Brioche Loaf, or 1 Brioche au Chocolat Loaf

Ingredients

⅓ cup warm whole milk (80°F to 100°F)

3 tablespoons (36 grams) granulated sugar

1 tablespoon (9 grams) active dry yeast

3¼ cups (406 grams) all-purpose flour, divided

5 large eggs, room temperature

1 teaspoon (3 grams) kosher salt

1 cup (227 grams) unsalted butter, softened

Instructions

In the bowl of a stand mixer fitted with the paddle attachment, combine warm milk, sugar, and yeast. Let stand for 10 minutes. Add 1½ cups (188 grams) flour and eggs, and beat at medium-low speed until smooth, 2 to 3 minutes. Remove paddle, and cover; let stand for 30 to 45 minutes. At the end of this initial fermentation process, there should be small bubbles forming around the edges of the mixture.

Replace paddle attachment with the dough hook. Add remaining 1¾ cups (218 grams) flour and salt. Knead at medium speed until dough pulls away from sides of the bowl and is smooth and elastic, 8 to 10 minutes.

With mixer running at medium speed, add butter, 1 tablespoon (14 grams) at a time, letting each piece incorporate before adding the next. Spray a large bowl with baking spray with flour. Place dough in bowl, turning to grease top. Cover and let rise in a warm, draft-free place (75°F) until doubled in size, 1½ to 2½ hours.

On a lightly floured surface, turn out dough and fold a few times to knock out a bit of air. Return dough to greased bowl; cover and refrigerate for at least 8 hours or overnight (up to 16 hours).

Bake From Scratch

0 notes

Text

An Eating Adventure in Uruguay

By Gabe Ulla

Photos by Marcus Nilsson

Saveur | April 16, 2015

"I bet you idiots didn’t even know that Jesus Christ was born in Uruguay.”

Ignacio Mattos is on a roll, making up facts about his homeland and entertaining us with mock-rhapsodic commentary as we drive directly from Montevideo’s international airport to the first stop on our journey: Bar Arocena, a dusty snack bar near the beach.

“There’s much you don’t know about these majestic lands,” Mattos says. Which is indisputable, as the itinerary he’s put together has been light on specifics. The three-day plan consists of a handful of bullet points, with activities ranging from “we could go here” to “maybe we stop at a bar in this area.”

About this first stop, though, we are well informed. Mattos has been talking it up since we boarded the plane in New York, where (with the dapper sommelier Thomas Carter) he runs Estela, an always-packed, two-year-old Manhattan restaurant. In Estela’s tiny kitchen, Mattos cooks food that’s comforting and straightforward, but with deft little surprises here and there that make it alluring and completely his own. It’s a bustling downtown spot where the bar is always at least two-deep and the Obamas shared a date night last fall.

Carter’s never been to Uruguay before, but he takes the wheel of the rental and somehow we make it to Bar Arocena without incident. We’ve arrived for our first lesson about this hallowed land, in the form of the massive, mythical chivito, the unofficial national sandwich of Uruguay.

Next door to the city’s Baroque-inspired, palatial Hotel Carrasco, Bar Arocena is a world apart. It’s a narrow dive, and nothing inside—from the ceiling fans to the soccer banners that adorn the walls—seems to have been altered since it opened in 1923. They serve a variety of substantial dishes 24 hours a day, including milanesas (schnitzel, basically) and entrecôte steaks to share. But you go to Arocena to face off against the chivito, an impressive pile of ham, lettuce, tomato, melted mozzarella, hard-boiled eggs, pickled red peppers, beef tenderloin, pancetta, and mayo.

[Uruguayan Steak Sandwich (Chivito)This is chef Ignacio Mattos’ version of a hearty cheesesteak sandwich that is served in restaurants and cafés throughout Uruguay.]

It’s not the first thing you’d think to eat on a hot day. Yet it’s somehow a completely energizing ritual: Tackling the thing is precarious and engaging as you parry with it, wondering how many bites it’ll take for everything to fall apart. Once it does, you barrel through with your hands, a fork and knife—whatever it takes—intermittently digging into the plate of fries at the center of the table and keeping yourself going the whole way with ice-cold glasses of Patricia Red, the country’s popular light lager. The trick, I learn, is never to take a break.

Fortified and properly oriented in the ways of the chivito, we have a general plan to make our way to the town of José Ignacio, on the southern coast. Over the last few decades, it has become South America’s version of Montauk: a coastal village peppered with inns and resorts, popular mostly in the high season (Christmas to mid-February), where vacationers like to hang on the beach and throw the occasional party.

It’s here that Mattos came into his own as a chef. In the late 1990s, before he ever dreamed of moving to the States, he worked summers in the kitchen of Los Negros, the restaurant of grilling luminary Francis Mallmann. And it’s probably here that he picked up the nickname “Nacho.”

“I need a shower,” Carter says, breaking the silence as we get up to leave. He crumples the last of the napkins and tosses it onto the plate. We set off for the coast.

It takes about two and a half hours to get to where we’re going. The green and arid motorway is populated by mini-malls and auto shops that suddenly give way to the blue and tropical scenes in and around the city of Punta del Este. Each village we pass gets smaller and beachier than the last, until finally we arrive at Posada Paradiso, in José Ignacio. It’s exactly what you want from a low-key bohemian beach inn: 23 simply appointed rooms surrounding a pool. There’s mate tea available at all hours of the day. And once night falls, there is complete silence.

It’s late now, but Mattos assures us we needn’t rush. “Around here, it’s normal to sit down for dinner at 11 p.m.,” he says. It takes all of what seems like two minutes to drive over to Marismo, a candlelit, open-air restaurant, for a laid-back feast. Almost everything, from the traditional provoleta (crisped provolone cheese with pickled vegetables) to the meltingly tender eggplant and lamb shank, is cooked over an open flame. As we’ll find out during the course of the next few days, that’s the way they like to do things here.

[Uruguay Chivita Bar Arocena fries beer lunch]

La Caracola is a chic day club about 10 minutes northeast of José Ignacio. It sits on a sliver of land flanked by lagoon and ocean, accessible only by a small dinghy across choppy waters. Normally the beach hut is packed with vacationing swimmers, but today it’s closed, so Nacho has taken over the place.

What Mattos had described in his understated way as “cook a lunch for friends at the beach” turns out to be a more significant production. After being bounced around and drenched on the dinghy, Carter and I are greeted by waitresses arranging tables and bartenders fixing drinks. Toward the back, in the slender kitchen, Mattos is wearing all white and a floppy green hat that instantly brings to mind a cross between Pharrell and Chico Marx. His eyes are tearing up from the heat of the huge brick oven where he’ll soon be roasting whole fish that are currently hanging on a wire at the entrance of the restaurant.

We are introduced to the supporting cast of cooks arranging the radiant mise-en-place for the affair. Fernando Aciar pours olive oil from three feet above a bowl, making mayonnaise like an Asturian pours cider. Gonzalo Zubiri grew up with Mattos: “He took me out of Santa Lucía when I didn’t know what rosemary looked like and taught me how to work in a kitchen.” Zubiri tells me this almost instantly, pausing from scaling fish to make sure I take note of the visiting chef’s significance around here. Santiago Garat, a lanky man with the appearance of a Cuban revolutionary, tells me, “When I started organizing this lunch, people came out of the woodwork telling me they wanted to hang out with Nacho.” As guests loosen up over caipirinhas, the chefs talk through the finishing touches of what they’re going to serve. It’s an improvisational process, a kind of informal reflection of how Mattos likes to work in New York. Today in José Ignacio, the main attraction is the black corvina, sea bass, stuffed with lemon and herbs and roasted whole over a wood fire. There’s also addictive crab toast, bright with the flavors of capers and chile; a bit of tomato-and-basil salad; and some citrusy corvina cruda that features Mattos’ trademark use of thinly sliced vegetables—in this case turnips—layered on top of the fish, not just to add some bite, but also to give the diner a feeling of discovery. By the time we eat “lunch,” it’s nearing 6 p.m.

More than 40 people, friends and friends of friends, have descended on La Caracola.“When you’re with Ignacio around these parts,” Garat says, “there is no such thing as a small affair.” After the food is cleared, almost everyone sticks around to drink Campari and nap.

The next day we drive inland to a 1930s cattle ranch, La Rinconada, lined with massive eucalyptus trees. Beams of sunlight poke through the foliage and horses roam freely throughout the grounds. There’s a nice pool, as well as a trampoline for us to use just in case we’re in the mood for jumping on it between meals (we are). Lunch today is for a smaller but still lively gathering of friends. Many familiar faces from La Caracola are gathered around the patio. In the outdoor kitchen, Mattos, Aciar, and Garat kick off the traditional South American grilling ritual, the asado. “You can smell firewood and smoke everywhere around this country,” Mattos says, applying slabs of coronilla, eucalyptus, and acacia wood to the hearth. The meats are to be cooked over the red embers raked to the right of the grill, with the logs burning into charcoal on the left side. This will allow the meat to cook slowly, but ensure it isn’t overwhelmed by the flavor of smoke.

The plan is at some point to sit around a table set out on the grass, but food starts coming to us as it’s ready. Sweetbreads are the first to arrive, crisp on the outside, perfectly smooth within. Mattos liberally administers lemon and salt to almost everything he’s making. The relentless assault continues with two types of blood sausage, chorizo, tri-tip, short ribs, and a decadent cut called the arañita, from the rump, which we’re told the local butcher prepares only for select customers. “The meat is pleasantly fatty and full of character,” Mattos says. “It has that chewiness we love in Uruguay.”

The only condiment you need for all of this is chimichurri, that iconic South American sauce made with oregano, garlic, olive oil, vinegar, and chile flakes. Garat has laid out flaky, freshly baked galletas de campo (savory biscuits whose name literally translates to “cracker from the woods”) so that we can fix ourselves small, open-faced sandwiches and dip into the juices.

The flavors today are heavier and certainly meatier than what Mattos champions in New York, but I can see the same purity and simplicity that form the foundation of his cooking at Estela. Carter suggests we make this trip every year. He’s got a bit of chimichurried bread between his fingers. “There’s a community in this place that’s just incredible,” he says. “You could talk to these people for hours.”

[Mattos makes a smashed potato salad]

That’s exactly what we do after sitting around the long table on the lawn to finish off the Malbec and dig into the flan that Clo, the owner of the inn, has prepared for dessert.

Nacho is finally done cooking for the weekend and sits with us. He’s not usually given to nostalgia, but these reunion feasts have put him in a reflective mood. “When I started cooking in José Ignacio, I was questioning whether I wanted to work in kitchens for the rest of my life,” he says. “But I was embraced here in a way that triggered whatever it is my life has become.” Everyone seems sated, running their fingers around the rims of plates to get those last few bites of sweetness.

Saveur

"An Eating Adventure in Uruguay." Saveur Magazine. May 2015. Issue 174. Editor in Chief Adam Sachs. Publisher Kristin Cohen. Published by Bonnier Corporation. Winter Park, Florida. Pages 72-78.

0 notes

Photo

Where to Taste San Francisco’s Most Iconic Dish

By Serena Renner || Oct 8, 2015

Afar || From the November/December 2015 issue

Photos by Jake Stangel

For 165 years, Tadich Grill in San Francisco’s financial district has operated at the same rhythm. Salmon sizzles under the broiler, white-jacketed bartenders stir and shake lunch-hour martinis, and servers hurry by with bowls of the restaurant’s famous cioppino, a tomato-wine stew brimming with clams, mussels, shrimp, whitefish, and Dungeness crab.