Text

5 July 2023

The First Man

Paris

5 July 2023

At 11am on the 11th of November 1918, the guns fell silent - on the Western Front, at any rate. The Russian Civil War, with British, French and American intervention forces, still raged, and violence in Germany, the Baltic, the Balkans, Turkey and the Middle East would continue well into the 1920s. Then there were the millions who had survived the war only to be struck down by the Spanish Flu, whose spread had been accelerated by the movement of armies.

For those who had survived the trenches and the 1918 Offensives, though, it was finally, truly over. Some men cheered. Others regarded the end with stunned silence. I remember reading a quote in Peter Hart’s book on the last month or so on the war - I think it’s called The Last Battle. Some Australian officers wait together as their pocket watches strike the hour. Silence falls over them, until at last one of them speaks; “What now?”

What now indeed? The men had to be demobilised, and the dead properly interred. A sense of grief enough to flood the world had to be processed. Some, of course, had no body to bury; their sons had been blasted to ribbons by shrapnel. Surrogate graves were needed.

As early as 1916, the idea of entombing a private soldier in the Pantheon in Paris had been proposed. This was proposed in the French Parliament less than a week after the armistice, and signed into law in September 1919. At some point, the site of this ‘unknown soldier’ was shifted from the Pantheon to the heart of French military glory, the Arc de Triomphe. Eight bodies were taken of eight of France’s bloodiest battlefields to the very heart of French resistance, the city of Verdun, and Corporal Auguste Thin was chosen to pick one of the coffins. He chose number six, based on his regiment - the 132nd. One plus three plus two.

The body arrived at the Arc de Triomphe on Armistice Day 1920, but was not buried under that great arch until January 1921. In 1923, a sacred flame was placed at the head of his tomb. The flame is rekindled each evening at 6.30pm - even in the Nazi Occupation, this ceremony was carried out.

France and Britain buried their unknown soldiers at the same time, and the idea for both seems to have come about in 1916 - but France began the process of actually doing it before Britain. In doing so, they could perhaps be said to have completed the Arc. For the only body interred in this great monument to Napoleon Boneparte and his marshalls, and the only body that ever will be interred there - at this building far grander than Napoleon’s own tomb - lies a humble private soldier.

Even Britain’s Unknown Warrior must share his space with kings and lords. For this poilu, the heart of Paris is his alone.

We were shown the Arc and the Unknown Soldier this morning by Romain Fathi, who I must say was excellent company. After that, we were free to wander the city, and naturally I headed to Les Invalides, the site of Napoleon’s Tomb and the Army Museum.

The French Army Museum, or Musee d’Armee, is well worth a visit, be you a medievalist, a Napoleon buff or someone interested in the World Wars. I did three galleries (and the Charles de Gaulle wing in the basement, but that was very technological and I found that disappointing.) My favourite part was definitely the gallery covering the 18th and 19th centuries - the wars from Louis XIV to Napoleon III. The Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars understandably dominate this section, and I enjoyed those artefacts, but I think I preferred the pre- and post-Napoleonic stuff more; in particular the transitionary uniforms and equipment of the Restoration period between 1815 and 1848. It’s also quite entertaining to see what the museum glosses over - for some reason, they don’t go heavily into Waterloo. Probably because they Waterlost.

The arms and armour wing, which covers the 13th through to the 17th Century, isn’t quite my thing (except, of course, for the 17th Century stuff, as I’m a bit of a closet English Civil War buff.) That said, the armour collection in there is very impressive, and I can see a medievalist having a whale of a time in it. There’s even some Japanese and Chinese stuff - although maybe we shouldn’t think too hard about how the French got these treasures.

The World Wars section was good, but not good as I remember it being in my last visit several years ago - perhaps its a case of rose-tinted memory. Still, there’s a lot of very interesting stuff in there - particularly French stuff, which really shouldn’t be surprising. One thing that amused me was the wing’s total refusal to show British kit unless they absolutely had to - there are three cabinets which contain any British uniforms in the First World War section, one of which is dedicated to the war in the Middle East generally, and one of which is mostly about the Dominions. The WWII section is even better - the only place they show much British objects is in the Normandy section, where they wouldn’t have been able to get away with excluding them. The French Army is credited as being the sole - not one of, the sole - reason that Dunkirk worked.

You might ask why I’m complaining about the lack of British representation in the French Army. First of all, I’m not, I think this is hilarious. It just sticks out when the French have big parts of the museum dedicated to the Eastern and Pacific Fronts, fronts which mostly neither concerned France or had many Frenchmen in them, and are happy to include lots of American objects, but go out of their way to exclude Britain as much as humanly possible. Basically, it’s the story of how the great allied powers won the war - the US, the USSR and France, with a tiny participation by les fuckuers who abandoned them at Dunkirk. Never change, France, never change.

After the Sir John Monash Centre, I really don’t have any right to be cross. Everyone does this - we do, the French do, the Turks do, the Yanks certainly do. We all play ourselves up, in war, politics, society and sports - just look at the cricket, where it’s okay when Australia cheats but if England cheats we need to go to war (and vice versa, of course.) We should strive to tell history as accurately as possible, free from the blinkers of nationalism - as they try to do at Ypres and Peronne and even the IWM - but we can’t really be surprised at museums that don’t.

I emerged from the gift shop next to Napoleon’s Tomb, but as I approached, I discovered that I’d managed to lose my ticket - I’m still not quite sure how, but I think it might have slipped out of my bag while I was getting my wallet out to buy a magnet. For a moment, I was frustrated - but then I thought about it. I’ve seen enough dead people, enough cemeteries, enough tombs. Who is Napoleon Boneparte but another man? Why is he so important that I must pay to visit him - heck, I don’t even respect him! Strip away the pretence - the First Consul, l’Emporeur, the Conquerer - and he’s no better than you or I. When one has seen those graveyards full of indispensible man, a monument to a conqueror seems rather trite.

So I left, walking out of Les Invalides through spitting rain, past the cannon and the mortars towards the Metro, bound back to my hotel to ruminate on more peaceful matters.

The End

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

4 July 2023

These Green Fields of France

Paris

4 July 2023

On the 1st of July 1916, a thousand tragedies played out in a thousand places. It seems monstrous to classify them as ‘better’ or ‘worse’ than any other, but perhaps one of the saddest stories of the entire war happened at Beaumont Hamel, a short distance from Thiepval and Pozieres. It was here that the 29th Division, fresh from the horrors of Gallipoli, attacked. Among them were the Royal Newfoundland Regiment.

In the early 20th Century, the modern Canadian provinces of Newfoundland and Labrador were their own nation - the Dominion of Newfoundland. Their population was small, but they managed to raise a battalion - the so-called ‘Blue Puttees’ - to fight in France. They’d diverted to Suvla Bay on the way, but now the 780 active officers and men had reached the Somme, ready to take part in Britain’s largest push of the war. These men did not consider themselves Canadian - they were Newfoundlanders and proud of it, and likely had more bond with the British of the 29th, who had shared the experience of Gallipoli, than their neighbours in the CEF.

That July morning, the 29th’s attack, like most divisions on the northern and central parts of the Somme front, was meeting with disaster. The 86th and 87th Brigades were bogged down before the German wire, and the GOC, Major-General De Lisle, had no way of knowing precisely what was becoming of his men. Reports came in that British troops had apparently broken through - if so, they needed support. De Lisle committed the 88th Brigade, the Newfoundlanders amongst them.

The British trenches were so clogged with the dead and wounded that the regiment was forced to go over the top from a support trench 250m behind the British front line. As they emerged, they were suddenly the only moving troops visible to the Germans - all of the enemy’s fire fell upon them. Ahead in No Man’s Land was the ‘Danger Tree,’ a skeletal husk that was meant to be used as a way point, towards which the Blue Puttees now headed. Unfortunately, the Danger Tree was known to the Germans, who had the area presited for artillery.

As far as I’m aware, none of the Newfoundlanders made it anywhere near the German line. It was the Nek played out in France, but drawn out and - incredibly - even worse. Of the 22 officers and 758 men of the Blue Puttees that set out that day, only 68 were present at roll call the next day. When General De Lisle reviewed the situation, he made a poignant, perhaps even somewhat self-critical, remark - “It was a magnificent display of trained and disciplined valour, and its assault only failed of success because dead men can advance no further.” Only one battalion - the 10th West Yorkshires - suffered worse casualties.

Newfoundland never recovered. The high casualties, combined with the Great Depression and political scandals, led to the revokation of responsible government in the 1930s and the absorption of Newfoundland into Canada in 1949. 1st July, for most Canadians, is Canada Day, but for the people of Newfoundland and Labrador, it remains a day of mourning. It’s a graphic reminder of how war can destroy not only men’s lives and bodies, but the hopes and dreams of whole peoples.

We left Amiens at 8.30 for our last battlefield tour - it feels like years since we first scaled Plugge’s Plateau. Our first stop was the Querrie British Cemetery. I had reached the point by then where I felt entirely numb to cemeteries; even the most intimate of epitaphs failed to get through an emotional weariness created by seeing grave after grave after grave. I was hit a little by one discovery - in this cemetery for the men of the war to end all wars, there’s a British pilot shot down during the Battle of France in 1940. But even then, that was a moment of pause rather than an emotion - a brief moment to say ‘huh’ rather then anything deep and moving. I thought there was no more the Western Front could give me.

Next we went to Pozieres Windmill (after swinging past Albert for photos of the famous tower), which I’ve visited before. I still like the area - the memorial to the Tank Corps is across the road, so I stopped to look at that before following the group to the Windmill. The first thing you’ll notice about the Windmill is the lack of a windmill - there was one, once, but it was blasted apart by artillery during the ferocious battles on 1916. This is the place that Charles Bean described as being ‘more densely sown with Australian blood than any other place on Earth.’ In six weeks, as many Australians died as during the whole Gallipoli campaign.

When I last came here, there was a field of little hand-made crosses dotting the field beyond the craters. You could walk straight out there and stand amongst them - and to the WWI Animals Memorial, which is behind the Windmill. No more. A hedge blocks the way now, as if the Animals Memorial is too vulgar to share space with the Windmill site, and the crosses have been cleared away. Instead there’s a Hollywood Sign styled collection of words dominating the view from the tallest crater, screeching ‘POZIERES 1916 LEST WE FORGET’ at the viewer, and beyond that a carefully manicured bed of roses. I know not who did this, but it feels like the initiative of a Big Man - the Mayor, perhaps, or the DVA - thrusting aside the small, thoughtful memorials of the peasantry to make his own statement. So often this seems to be the case - be it Howard and Abbott’s hundred million dollar baby under the graves at Villers-Bretonneux, or the carefully choreographed dawn services at Anzac that replaces the small ones at the Beach Cemetaries. Memorial culture is dotted with Big Men with Big Ideas and Big Egos, and I think the world would be a better place if they left things well enough alone.

The caretakers of the battlefield at Beaumont Hamel did precisely that.

There were three artificial things I found at Beaumont Hamel, excluding the footpaths that allowed the visitor to navigate the site. The first was a small museum, basically built in a cabin that sits out of the way. The second is the big caribou monument built in the 1920s, the giant animal facing into No Man’s Land as if calling the souls of the dead home. Finally, there’s a modest replica of the Danger Tree installed to give visitors an idea of where it was. Otherwise, the battlefield, bought by the Newfoundland government and now owned by the Canadians, is left as it was for nature to reclaim. The shell holes and trenches remain, but they’re covered in grass now, and there’s patches of forest and trees. The Beaumont Hamel battlefield has returned to the Earth from whence it came, and I found that my capacity to care had not been exhausted after all.

Standing next to the site of the Danger Tree, staring out into No Man’s Land, thinking of the futile deaths of hundreds of men, and hearing the distant sound of birdsong and feeling the warm sun, I felt the urge to shout out at the sheer folly of it all, to forcibly drag the group, who I felt weren’t appreciating the site possible, to the cemetery beyond to read the names. How could you stand here and not feel? How could you still talk and laugh and joke about small nothings in a place like this?

But then I talked to Maddi, and she gave me a different perspective. Of course they laugh and joke. That’s how they process going to cemetery after cemetery after cemetery. People react to confronting sites differently, and just because I might think someone’s being disrespectful doesn’t mean they are - or at least not intentionally. I think they laugh and joke about things happening in the world today for the same reason I started to go numb - because if you focused on all the grief and loss we’ve seen this past few weeks, if you made yourself feel every bit of it, you’d go mad. And did I not laugh at the Sir John Monash Centre, sitting as I was under the graves? Who am I to criticise them? Did not the soldiers I was thinking about use black humour to cope with their situations?

People are strange, and I sometimes have trouble really understanding them. I think every does, but some are better at hiding their puzzlement at humanity.

We stopped at Ulster Tower to eat in their cafe, but they weren’t serving food so we cut our losses and ate at a service station near Albert. We then went back out to Thiepval.

The Thiepval Memorial was once described as a structure consisting of ‘deranged arches,’ and that critique isn’t entirely wrong, but I’ve always found it strangely beautiful - more so than the more famous Menin Gate. This discordant memorial, situated in the middle of the most beautiful part of northern France, lists the names of the missing of the Somme; British and French. I don’t know what the group discussed here, because I walked up the steps alone. I found a name for a family member, then stepped up to stand under the central arch, where the stone reading ‘their name liveth forever more’ resides. From here, you can see the cemetery - French to the left, British to the right, the Cross of Sacrifice between them.

I walked down there. Normally I’d walk among the graves, looking for interesting epitaphs, but this time I just sat down in front of the unknown soldiers and, as Eric Bogle’s famous song goes, sat for a while ‘neath the warm summer sun. Just me and him, whoever he was.

There is no such thing as a necessary war - even when you’re fighting to defend yourself or someone else, you’re doing so because somebody attacked you. There is no glory, and fundamentally no point, in trying to achieve political goals through military might. All those great ‘heroes’ of conquest - Alexander, Caesar, Napoleon - I find them contemptous. War is young men - kids, even - dying for old men. It is violent, it is grotesque, and any statesman who would consider it anything more than an absolute last resort isn’t worth their salt.

There’s heroism in war, I will say that - the fighter pilots of the Battle of Britain, the Allied troops who stormed Normandy, the stretcher bearers who risked life and limb to save others. Mostly it’s just killing and dying. I can’t look at the Newfoundlanders, or the men at the Nek, or Bullecourt, or Chemin des Dames or Passchendaele or a thousand other stories of military failure across history - and say they ‘sacrificed’ for us. They died for nothing. They didn’t shorten the war by a single second. They didn’t die for our freedom. The only way we can make these deaths mean something - anything at all - is to endeavour never to let waste like this happen again. To research their histories, to tell their stories, to reveal everything warts and all, and hope and pray that the lesson will stick.

Maybe one day we’ll learn.

We’re in Paris now - our last teaching exercise is tomorrow. I’m filled with a sense of melancholy, but at the same time relief. I think I’m about ready to step out of the front line.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 July 2023

Oh It’s A Lovely War

Amiens

3 July 2023

By the end of 1917, time was running out for Germany. Russia may have sued for peace, but the United States had entered the war, and Generals Hindenburg and Ludendorff, now effectively dictators of Germany, knew that numbers would soon inexorably favour the Allies on the Western Front. Ludendorff needed one last masterstroke - a decisive battle to destroy the French and British before the Americans could arrive.

The great offensive - Operation Michael - was aimed at Gough’s Fifth Army, still exhausted from the hell of Passchendaele. On the 21st of March 1918, after a sudden and violent artillery and gas attack, German stormtroopers smashed into the Fifth Army, and although their losses were massive, they attacked with such force that Fifth Army gave way. For a moment, as Haig scrambled to plug the gaps in his line and Fifth Army’s command and control disintergrated, it looked Germany might actually win the war.

It is here, in the popular narrative, that Australia stops them at Villers-Bretonnaux. In reality, there were two battles here that sometimes get conflated into one. At First Villers-Bretonnaux, British and Australian troops managed to halt the German offensive just short of the town. This wasn’t the only place where the BEF had managed to blunt Micheal - Arras held, and while the Germans had taken Albert, they had advanced little further. It was however the final nail in the coffin for any German effort to take the vital railway hub at Amiens. The Germans made a second attempt on the 24th of April and briefly captured the town, but were repulsed by a counterattack the following day. The popular idea here is Chunuk Bair in reverse - the British ‘lost’ the town and the Australians ‘retook’ it. In fact it wasn’t so simple - two Australian and one British brigade took part in the counterattack, alongside French Moroccan troops to the south.

It was a significant victory, but it didn’t stop the Germans completely. Ludendorff launched more offensives throughout the spring (including towards Hazebrouck, which was defended by First Australian Division and several British divisions.) Against all of them, the Allies held, although the fighting was hard and the cost was appalling. The cracks in the German strategy began to show - more and more American troops were being moved in front of them, and more and more of their best men were being killed. The end of the Spring Offensives came at the Second Battle of the Marne, in which chiefly French but also British, Italian and (for the first time in significant numbers) American troops decisively stopped Ludendorff’s last throw of the dice. No one country can claim credit for this - stopping the Spring Offensives required the full effort of every major participant in the Allied order of battle. It was a team effort.

Some people don’t seem to understand that, and sadly they’re often the people in charge of commemorating the war. Which brings us back to Villers-Bretonnuex.

Our first stop today was Adelaide Cemetery, just outside the town. If the name seems familiar, it’s because I’ve mentioned it before, although it seems like years ago now; this was where the Unknown Soldier was exhumed. Today, his former spot is marked with a special inscription, but otherwise the plot has the same shape of tombstone as everybody else. One might lament that he’s been removed from a peaceful plot in France to the hustle and bustle of Canberra - if, of course, they didn’t know that Adelaide Cemetery is sandwiched between a major road and a railway line, so he probably would find the AWM more peaceful.

We went from there to the Australian Memorial outside Villers-Bretonneux. John Monash Centre aside - and I swear, we’ll get to that soon - this is beautiful site, nestled amongst rolling hills and endless fields of wheat. To get to the main monument, you pass between two cemetery plots, as if the graves are lined up on parade - these are largely Australians, but there’s also a lot of Canadian and British soldiers who lost their lives in the battles around Amiens in mid-1918. You pass through two flag poles - French and Australian - and reach the main facade, in which the names of Australia’s missing in this sector of the front are carved. In the middle is a tower - it still bears the scars of the war that followed the war to end all wars.

Visitors can climb the tower, where they can get a commanding view of the countryside. You can see the town itself, and the distant shapes of other strategic features - for example Le Hamel, which we’ll talk about at the end of this log entry. Even if you’re not interested in military minutia, the view is amazing.

It was as we left the tower that one of the most curious and strangely moving episodes of this tour occurred. As I walked down the front steps, I saw a man with a bugle in British service dress - the uniform of the British Tommy - and an officer trudging up to our position. Somehow, in the middle of France, I had encountered some reenactors. It turned out there were seven of them - three men in Welsh Guards uniforms, a Highlander, a nurse, and two members of the Royal British Legion. They’d been deputised by an Australian family to pay tribute to one of their members lost in France during the war.

Suddenly, we were conscripted into this odd little ceremony. We gathered around - the bugler sounded the Last Post, there was a minute’s silence, and then two of us left a wreath in the tower as the Highlander played his bagpipes. It ought to have been very silly, this memorial service with these men in old uniforms, recorded on an iPhone for a faraway family. And yet I teared up. I don’t know why this got me, but I think part of it is the spontaneous nature of the event. These guys were from Wales and England. They had no obligation to pay one of our men this heed - and yet they did, and they went to such effort to do it. We even sang the national anthem together - I can’t remember the last time I actually sang it.

We interrogate forms of remembrance a lot on this course - it’s kind of the point - and we did have a little discussion of this a bit later. Sometimes I feel we as historians can be a little too cynical about this sort of thing. I don’t know if crossgeneration or surrogate grief is something that can be quanitified, but it was real for them, and I think that’s what really mattered.

And then we went into the Sir John Monash Centre. And oooooooh boy.

Remember how I said the museum at Peronne didn’t meet my expectations? Well, this exceeded my expectations, and it did so triumphantly. I expected that this would be bad, but what I got was a nearly heroic example of utter shitness. It crosses the line into utter inappropriateness, speeds right across the world like the Flash, and crosses the line a second time. I’m almost impressed.

First of all, everything - everything - is digitally integrated. You actually have to install an app onto your phone andhave headphones plugged in (or rent them for three euros) to understand anything that goes on here. You then walk up to screens - it’s almost entirely screens, like a sale at Harvey Norman - and press the number of the screen - except if its already playing, the recording just picks up where it already was, which is often halfway through the video. If the screen is out of order, well, no content for you. The inevitable question, of course, is how would you interact with this if you were blind, or deaf? I guess being deaf is just un-Australian.

And the content? I will be fair here and say nothing is technically incorrect, or at least nothing I was actually able to view and hear. My problem is more about what the museum doesn’t say. Monash’s somewhat indifferent career commanding 4th Brigade is neatly glossed over. So too is the Hindenburg Line battle of 29 September, and don’t worry, we’ll get to that. Every other combatant in the war is a footnote, which gives the impression that Monash and the Australians are personally winning every major battle of 1918. Then there’s the language - Australian units withdraw, while British units are shattered. All this is underlined with dodgy, overacted dramatisations and a tactical war that uses 3D models to showcase the battles of Fromelles, Polygon Wood, Amiens and St. Quentin - all rather badly posed, and all looking like they came out of a pre-alpha version of Battlefield 1.

Then there’s the experience. The experience is what this whole thing is built around - the brilliant idea to have a light and sound show right beneath the graves of the dead, giving the visitor a feel - as if that’s possible - of what the Villers-Bretonneux and Hamel battles were like. I actually managed to get a session where I was the only oneside when it started (the door shuts while it’s playing.) I am truly thankful I was. When the government commissioned historians to plan this, they outright said that they wanted visitors to feel ‘pride with a touch of sadness.’ It would probably be difficult for audiences to feel such emotions if they were sharing a room with a university student pissing himself laughing.

Yes, this is conceptually appalling to me - but it’s also so silly that I couldn’t help but laugh, and laugh hysterically at some points. After opening with British troops fleeing Operation Micheal, literally screaming and crying - I’m surprised the director showed enough restraint to stop himself from staining all their trousers with wet patches - a sinister German voice who’s probably meant to be Hindenburg but sounds more like Major Toht from Indiana Jones declares his intention to destroy the British. The viewer is ‘gassed,’ which feels more like sitting in a smoking room at Hong Kong Airport. Then come the brave, steely-faced Australians, counter-attacking alone into Villers-Bretonneux. They get into the Beastly Hun with their bayonets. Some die and it is Sad. One kicks in a door and hip-fires his Lewis Gun into three Germans Rambo-style whilst going “AAAAAAAAAAA” - and then I don’t know what happened for the next ten seconds because that scene was so ridiculous I started cry-laughing.

Then we move onto Hamel, and here comes the great hero, Monash. He points at maps. He walks next to tanks. He stares heroically into the distance. There are no other generals, or even other officers - there is only Monash. (I could almost feel the ghost of Pompey Elliot swearing up a storm next to me.) Monash unleashes his vague powers of tactics upon the Beastly Hun, and the Australians go in. The Germans all have gas masks and therefore have no faces, making it okay to kill them. The sound of artillery forms the drum beat of a Hans Zimmer style musical track as the battle goes on. There’s tanks. There’s explosions. There’s strobe lights. There’s another bloke hipfiring a Lewis Gun and going “AAAAAAAAA.” There are no Americans. Americans don’t exist. And then, because the director suddenly realised that this is meant to be a site of commemorative diplomacy, a brave Australian soldier waves a French flag. Monash has won the war.

If I tried to come up with a satirical depiction of Australian history, I honestly couldn’t beat this. It is sublime in its idiocy. I want this on DVD. I want to show all my family and friends. This might be the best First World War comedy since Blackadder.

Don’t get me wrong, I think this is very offensive and it shouldn’t be anywhere near a cemetery, let alone under it. But at some point, you just have to laugh.

Now there’s one big problem with the Centre, apart from everything else, and that’s the name. John Monash fought a lot of key battles in the Australian Corps’ history. Villers-Bretonneux was not one of them. I do wonder if there was another option here, to focus not on Monash but on Harold ‘Pompey’ Elliot, a superb brigadier who was haunted by his experiences of the war, and whose life was tragically cut short by the consequences of PTSD. At very least, he was actually there and played an important part in the battle.

The Sir John Monash Centre is not the best museum in France - in fact, it’s not even the best Australian war museum in Villers-Bretonneux. That laurel belongs to the French-Australian Museum in the town itself, which we visited afterwards. This is in the top story of the local school, which was rebuilt after the war with subscription money raised by Victorian schoolchildren. To this day, there’s a sign above their courtyard - ‘DO NOT FORGET AUSTRALIA.’ The museum is very small and very intimate, although perhaps a little scattered - it’s clearly a labour of love, a collection of a few treasured relics, models and artworks that connect this small French town with a country on the far side of the world. The assembly hall, which the staff kindly let us go into, is decorated by wooden carvings of Australian animals made by a disabled Australian veteran after the war. This probably cost a fraction of the Sir John Monash Centre, and is probably maintained by two staffmembers and a goat, but it is worth infinitely more than that supposedly ‘world-class’ installation.

Sadly, this museum doesn’t get many visitors anymore - all the tour groups want to go to the glitzy new thing down the road. So here’s my advice - go to the Australian Memorial by all means, but skip the Centre, unless you want a quick laugh. Come here instead. You won’t regret it.

The main teaching for today ended at Heath Cemetery, where we discussed some Aboriginal soldiers’ graves that we’d actually found out about at the aforementioned museum. It’s hard to find Indigenous soldiers - as Aboriginal people were banned from the armed forces, those that passed as white were hardly going to write what they were on their enlistment forms. It’s led to a significant part of the AIF’s history being obscured - but today, it’s being reclaimed as families find their veteran ancestors, dead or alive. In fact, one of the few things I liked about the Centre was an art installation of two emus made from (imitation) barbed wire - a symbol of these men who died so far from Country under an unfamiliar sky, with no Southern Cross to guide them home.

We headed back to Amiens, and most of the group alighted here, but a few of us - the cool members of the group - went back out to the memorial at Le Hamel. This is a curious memorial, but I don’t hate it - it’s basically a big slab in the middle of a wheatfield with the Australian, American, British, French and Canadian flags flying above it. (This is where the Red Baron was shot down, and as the Canadians still think they got him, they get to have a flag.) Plaques on the path to the memorial describe the course of the battle fairly well (although I feel they do a bit of an injustice to the Tank Corps, which are never mentioned by name.) Once there, you have a pretty good picture of the fields leading to Le Hamel, the town that Monash famously captured in ninety-three minutes on the 4th of July 1918.

Hamel was a great achievement, but it needs to be put into context - this was a local action in preparation for the real offensive at Amiens in August. Here Monash also performed very well, but so too did Currie and the Canadian Corps, and Sir Henry Rawlinson in overall command. (The British III Corps advance was less impressive, but still outstanding by Western Front standards.) Between Hamel, Amiens and Mont St. Quentin, Monash more than earned his reputation as an outstanding commander. But he wasn’t infallible, and now I can finally talk about 29th September 1918 and the St. Quentin Canal.

Monash and the Australian Corps were meant to be the main force here. IX Corps (remember them from Suvla?) were to swing south in a secondary role, while III Corps, whose commander had just been sacked, was mostly left out. By this time, Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes was insistent that the Australian divisions be taken out of the line for a rest, and this had already happened with the 1st and 4th Divisions. Monash and Rawlinson had managed to hold onto the 2nd, 3rd and 5th Divisions for this final action against the Hindenburg Line, but had had to replace the other two with the 27th and 30th US Divisions. These troops were nowhere near as experienced as the men they’d replaced, but Monash’s plan doesn’t seem to have accounted for that, and he used a strategy he’d used to great effect at Amiens - send two divisions in first, then leapfrog them with fresh divisions once the first wave had taken their objectives.

The Americans performed about as well as could be expected, and their bravery was in no doubt, but they didn’t know how to properly clear out the German trenches that they were advancing over. Inevitably, when the Australians came in, they ran into German strongpoints that had been temporarily suppressed, but not destroyed. This resulted in heavy casualties and bogged down the advance. A frustrated Monash took days to pound through, and with the benefit of hindsight, he really should have altered his plan to account for the greener troops - instead, he and Rawlinson, somewhat unfairly, blamed them.

All this was probably academic, because while the Australian Corps was pounding along, the Hindenburg Line had already been broken. Remember how I said that I didn’t think Mont St. Quentin was the greatest military achievement of the war? I define military achivement differently to Rawlinson. Taking a position against all odds is definitely impressive, but carrying out an operation so effectively that your troops don’t really need heroic daring do is quite another, and this was what happened on the IX Corps front in the south. The 46th Division at Bellenglise - as standard and normal a division as any - had swept across the St. Quentin Canal in perfect concert with their artillery, capturing an intact bridge and the village. For the loss of 800 casualties they captured over 4000 men, and tore a gaping hole in the Hindenburg Line that the following 32nd Division was able to exploit. This, in my opinion, was the outstanding military feat of the First World War - because so much was gained for such (by Western Front standards) a cheap cost. Rawlinson rightly shifted the main axis of his advance south to support it, and after a few more days of hard fighting, the Australian Corps was finally taken off the line for a well deserved rest. The war would end before it could return.

Well, that was a digression and a half. Tomorrow we leave Amiens, heading down into the Somme for the last big day of battlefield touring, and then onwards to the City of Lights itself.

Oh, one last story before I forget - our professor dug this up while looking through Monash’s correspondence for a history of Melbourne’s Shrine of Remembrance. Towards the end of Monash’s life, he began to think of what he ought to leave for Australia. As a war hero, he thought, he needed to leave them an example to look up to. As he was making arrangements for his legacy, he noted particular papers that he needed dealt with properly, as a matter of national importance.

So, shortly after he died, someone gathered these papers - I think his executor. As John Monash was buried in his modest grave, marked only with his name and eschewing his many honours, this person took them somewhere safe - perhaps an incinerator, or a bonfire in the bush. I can imagine this person, a tear in his eyes, a bugler playing the last post, as he was forced to consign a major piece of Australian history to the flame.

But duty called, and this man would obey. And therefore, with a heavy heart, he destroyed General Sir John Monash’s enormous collection of pornography.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 July 2023

The Death Drill

Amiens

2 July 2023

We must return again to the Hindenberg Line.

I mentioned earlier that the Hindenberg Line was eventually cracked. We’re still not there yet - that’ll be a discussion for tomorrow. I have, in fact, been very deliberate in waiting for that moment. As I mentioned on the 28th, the Hindenburg Line was a perfect defensive position, and one that the Allies encountered with some surprise during the Arras offensive. It did not blunt British ambitions - it simply couldn’t be allowed to. To the south, on the Chemin des Dames, General Robert Nivelle’s French offensive was drowning in blood, and Haig had to try and keep the pressure off of them. The Line would have to be attacked. Thus, the tragedy of Bullecourt.

Bullecourt - and given the black humour of the Tommies and the Diggers, I’m surprised it was never corrupted into ‘Bullet Court’ - was to be attacked by Hubert Gough’s Fifth Army in a novel way. There would be no preparatory barrage. The 4th Australian Division would attack by surprise with the support of tanks. In the event, when the attack was launched on the 11th of April 1917, barely any tanks arrived - they almost all broken down, and the few lumbering beasts that made it to the starting point were soon knocked out. Worse, the loud engines alerted the Germans. The Australians advanced into a funnel, covered on all sides by interlocking fire - some positions were taken but then lost by a fierce German counterattack. Three thousand men became casualties, and more men were taken prisoner here than in any other Australian battle. To add one final insult to injury, Gough, convincing himself that he had an exploitable breakthrough, sent an Indian cavalry brigade into the killing field, causing yet more useless deaths.

Something changed in the AIF after First Bullecourt. Gough’s reputation with them never recovered (and indeed, he was despised by pretty much everybody who had the misfortune of being under his command), even though some of the blame for the catastrophe should also be laid at the feet of Birdwood and some of the battalion and brigade commanders. The Australians would take a long time to trust tanks again, but in particular, a large part of the AIF lost faith in the old British Army. Most of this loss of faith was directed towards the generals and the staff, but Bill Gammage’s seminal work The Broken Years indicates that a great many men lost their respect for the ordinary Tommy too. The British, it was said, had let them down; they had no stomach, they couldn’t fight, they’d left the Australians in the lurch. (In fact, poor staff work had led the British 62nd Division to attack too early, with predictably bloody results.) I remember reading Gammage’s book a while ago, and some of the accounts felt like a few Diggers would have rather dug their bayonet into a British Tommy than a German soldier. Always be suspicious when you hear people talking about the brotherhood between allies.

(The British stereotype of the Australians was that they were overpaid and underdisciplined, and that they had everything you could ever want but still moaned about it, so lets not pretend this doesn’t go both ways.)

That tragic field of Bullecourt was our first stop of the day. None of the Australian divisions chose here to be their memorial, for reasons that are probably obvious, but a memorial was put in place to the battle in the 1990s. It depicts a Digger on a cairn, starting out towards the battlefront and the site of the Hindenburg Line. He looks almost casual, wearing his slouch hat with his rifle slung over his shoulder - yet there’s a somber weariness to his features. I don’t think there was any deep meaning to this figure when it was sculptured - more likely the DVA just said ‘STATUE PLEASE’ - so it’s interesting how the mind invents them when looking at statues like this.

We carried on from Bullecourt to Peronne, where the memorial to the 2nd Division stands on the slopes of Mont St. Quentin. It was here that the 2nd Division seized the heights from the Germans and held it in the face of several ferocious counterattacks, an achievement Fourth Army General Sir Henry Rawlinson believed was the ‘greatest military achievement of the war.’ (I actually disagree with Rawlinson on this, but that’s another thing to be discussed tomorrow.) The 2nd Division’s memorial is actually a replacement - the original might have been the most ‘metal’ of Australia’s war memorials, depiciting a soldier thrusting his bayonet into a Prussian eagle. When the Nazis came through in 1940, they spared most other war memorials - but they destroyed this one. It was replaced in the 1970s with a soldier looking down in thought. It’d diplomatic, and probably more appropriate - but I’d be lying if I said I didn’t have a sneaky desire to see the old one.

We continued into Peronne, and after lunch went into the Historiale de la Grand Guerre - the Museum of the Great War. This has been built up for me for years, the brainchild of Annette Becker and our spiritual liege Jay Winter. They are, of course, no longer with the museum as far as I know. I think this may be to it’s detriment, because the main feeling I felt here was a sense of disappointment.

This museum is still worth visiting, and I don’t know if it would ever have lived up to my expectations. Laying the uniforms and equipment at the viewer’s feet, as if laying in state, is not only artistically genius but surprisingly practical in allowing you to actually see what these artifacts are. There’s a whole section on the work of Otto Dix, a soldier who made print art of his experiences after the war. I won’t include any photos of these pictures, because while Dix’ works are amazing and everyone should see them, they are also, pardon my French, fucking horrifying.(The Nazis, being big on the whole war as national regeneration thing, banned them.) It does its best to cover as many perspectives on the war as possible, and while the pacifist bent here is obvious, it doesn’t get in the way of being a museum too much.

That’s a bit of a shame, though, because it’s the ‘being a museum’ category that causes it to fall down for me. There are so many errors that somebody really ought to have caught - a tunic of the Leicestershire Regiment is mislabelled as a Coldstream Guards tunic, which would be forgivable were it not for the giant ‘Leicestershire’ badges on the collar, clearly visible to the public. A tunic is described as belonging to a ‘Captain’ in the ‘Derbyshires’ - not only does it belong to a Lieutenant, there was no Derbyshire Regiment. That region was covered by the Sherwood Foresters. I’m sure this all sounds like rivet counting, but these are errors that are easily noticeable and easily corrected, and they’re in the first room. If they’re making basic factual errors in the first section of the museum, why should I, as a member of the public, trust what they say in the next? (And before someone asks if they simply mistranslated the name of the rank, lieutenant is a French word. The word for lieutenant in French is lieutenant. I don’t know how a museum of war could make this mistake.)

This annoyed me, but what got me really cross was a placard about the Hundred Days Offensives at the end of the war.

‘Without suffering any great defeat, the German Army was forced…’

Hold on, what?! Not only did the German Army suffer a great defeat, it suffered nothing but great defeats. What about Second Marne? Amiens? The St Quentin Canal, the Canal du Nord, the Meuse-Argonne Offensive? The Germans were defeated decisively and consistently on the field of battle, and I know a museum with a pacifist bent probably doesn’t want to throw around words like ‘victory’ in relation to war, when it comes to the Hundred Days, you have two choices. You have the history or the myth. The history was that Germany was decisively defeated. The myth was that it wasn’t. The myth is that the war was ended by the civilians - the socialists - while Germany was still capable of fighting. The myth is that Germany was betrayed by the socialists - and their perceived masters.

This is the genesis of the stab-in-the-back theory, one of the first steps on the road to the Holocaust. I know they didn’t intend for it to look like this, but that is what it looks like. You don’t have to necessarily say the Allies won, but you absolutely do have to say the Germans lost, and lost decisively. We cannot allow any academic or popular wriggle room for this antisemtic theory. (And for the record, I think you absolutely can emphasise this from a pacifist perspective. Talk about the suffering inflicted by the naval blockade, or the casualties of the Hundred Days. Just… don’t repeat antisemitic talking points.)

Sorry, I got a little bit angry there. Let’s talk about something a little more humorous - the cognitive dissonance one experiences when they leave this museum, Dix’ paintings still on their mind, and walk into a gift shop that’s selling faux-LEGO tanks, plastic helmets and poor quality hoodies with little Anzacs and Poilus shaking hands on them. It’s something of a mental whiplash, like I felt when I went into Rise of Skywalker expecting to have fun and then didn’t.

We went from there to Delville Wood, where the South African National Memorial is - a great shock, as I wasn’t aware they had one at all. The South Africans today are most known for fighting in East and Central Africa, particularly the running guerilla war with von Lettow-Vorbeck (in which 80% of their black African labourers got malaria and died.) Yet they did send a few battalions - all white men, of course - to the Western Front, where they suffered greatly in battles around here. The beautiful and sinister at the same time. For the most part, it looks a lot like you’d expect a First World War memorial to look - white stone, lists of the missing, inscriptions of battles - but over the arch in the centre is a message to all visitors - ‘Their ideal is our legacy. Their sacrifice is our inspiration.’

It seems a bit generic, but in the context of the Apatheid South Africa that raised this memorial, it’s downright chilling. What ideal are they talking about? We can’t exactly change the meaning of it - it’s ‘their’ ideal, not ours. For the first time, I found the white wall of the missing, amplified by the afternoon sun, to be deeply uncomfortable.

On a more positive note, the site has a small museum - and it’s free! If the memorial hasn’t been updated since the end of Aparteid, at least the museum has, with a frank discussion of the service and suffering of black South Africans during the First World War alongside the typical histories of battles and kit. What particularly stood out to me was the account of the sinking of the SS Mendi in a collision off the Isle of Wight, carrying black labourers to Europe. Oral tradition preserves the last speech of Reverend Wauchope Dyobha on the deck of the sinking ship. This was reproduced at the museum, and I’ll give you an excerpt.

“Brothers, we are drilling the death drill. I, a Xhosa, say you are my brothers. Swazis, Pondos, Basutos, we die like brothers. We are the sons of Africa. Raise your war cries, brothers, for though they made us leave our assegais in the kraal, our voices are left with our bodies.”

824 labourers were aboard the Mendi. Over 600 were lost to the sea. Reverend Dyobha was among them. They lived as servants of an uncaring empire, but I like to think they died as free men.

We carried on from there to Amiens, where I now have a glorious view of it’s beautiful concrete bus station. I saw a few memorials on my way to grab dinner, and I’ll try to take my camera out to get some pictures tomorrow evening if I have time, but I can’t promise anything. For tomorrow, we go to Villers-Bretennaux.

We’ve seen the tasteful ways Canada and South Africa use the spaces around their memorials. Surely, Australia would be just as tasteful, right?

Right?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

1 July 2023

Les Canadiens

Lille

1 July 2023

It would be remiss of me, even though we were not in that sector of the front today, not to mention the events that occurred 107 years ago today.

With the French pressured at Verdun, the British Army had been forced to take on the leading role in the Allies long-planned summer offensive. This was one of a series of major attacks agreed upon at an inter-Allied conference at the end of 1915; the Italians will attack (again) along the Isonzo, while the Russians prepare a massive thrust into Galicia. The western attack will fall on a hitherto quiet sector of the line - the region around the Somme River. For five days, one of the heaviest bombardments of the war so far had pounded the German lines. The ‘New Army,’ the name for the tens of thousands of recruits enlisted in 1914, was about to enter its first major engagement on the Western Front (excepting a few battalions used at Loos last September.) The expectation was that the artillery will have smashed the German positions to such an extent that the men could simply walk in to occupy them.

What the Allies didn’t know was that most of the German troops were not in trenches, but in dugouts deep underground, beyond the reach of the shells. After a hellish week under fire, the Germans emerged when the shelling stopped on the morning of 1 July 1916, reoccupying their positions and waiting for an attack they knew was coming.

There were some local successes, but the result along most of the line was catastrophic. Whole battalions were nearly wiped out in the killing fields of No Man’s Land - most infamously the Newfoundlanders and the 10th West Yorkshires, who suffered 90% casualties. Communications trenches were flooded with dead, dying and wounded, forcing reserves to go over from the rear trenches, where they were cut down before they could even leave their lines. Over 58,000 men became casualties, and nearly 20,000 were killed. It remains the worst day in the history of the British Army.

All of this is irrelevant to today’s events as we went to the Arras sector, but I figured it would be wrong not to mention it.

We had a later start today, as some students got the opportunity to discuss internships. We departed the hotel at 9.45 and walked to the Lille War Memorial, where we met our guide for the morning, Annette Becker. She guided us around the city and it’s memorials, including that to the civilians shot by the Germans during the war, the fortress built by Vauban in the late 17th Century, and the memorial to General and President Charles de Gaulle, who was born in Lille. We ended at a memorial to a massive munitions explosion in the 18 Bridges district, which killed about 200 and injured thousands.

This is one of the few times in this tour that we’ve really been able to talk about the role of civilians in war. Lille suffered more than most French cities during the Great War - it was occupied in 1914, and much of the population was deported. Some were shot for refusing to kill their pet carrier pidgeons, as ordered by the German authorities to prevent their use by spies. We were actually told, and I was surprised to hear this, that Lille’s occupation by Imperial Germany was actually worse than its occupation by Nazi Germany, the experience of the Jewish population notwithstanding. (There’s always been a sense of romanticism for the Kaiser’s Germany online. I think it stems from the social unacceptability of admiring the Nazis.)

We parted with Annette at midday and drove for Vimy - we didn’t go to Arras, that had to be bumped off because of the internship meetings. This country isn’t terribly pretty, but it’s strategic importance is clear from the landscape - the great slag heaps and chimneys that can be seen for miles around demonstrate that it was and is a nexus of coal and steel production.

Vimy Ridge is the first ridge worthy of being called such I’ve seen since arriving in Western Europe - unlike Passchendaele or Aubers, it’s visible to the naked eye, and indeed is quite a commanding position. It’s here that one can find the towering Canadian National Memorial. It was here that, in April 1917, four divisions of Canadian troops, fighting together for the first time, captured the Vimy Ridge from the Germans, a position that had been considered unassailable. There are some caveats here, of course - the Canadian Corps commander was the British General Sir Julian Byng, and a British division also took part - but it was nevertheless quite the achievement. (Arthur Currie, who is sometimes erroneously called the commander of the Canadian Corps at this time, hadn’t been promoted to that position yet but was in command of the 1st Canadian Division.)

The Canadian Memorial is truly monumental, the pillars towering above it almost forming a ‘V’ shape - V for Victory, Vimy or Valour, I could not tell you. The names of Canada’s missing, save for those on the Menin Gate, are listed around the base, while the names of the CEF’s battles from 1915 to 1918 are etched on the pillars. On the side facing Arras is a crucified man and a grieving woman, and various other figures of valour or grief adorn the structure. At the bottom of the memorial, again facing Arras, is the marble form of a coffin, a discarded sword and a Brodie helmet laid on top - a final funerial touch to what one of my comrades described as a supersized CWGC headstone. I’m not certain of the resemblance myself, but I can see where she was coming from.

About a mile’s walk from the memorial is the information centre. To get there, one has the pass the largely undisturbed site of the battle, pockmarked with craters, old trenches and the occasional chasm created by a mine. These areas are roped off, as unexploded munitions remain in the fields - although farmers allow their sheep to graze there. One hopes they are lightfooted.

The information centre is staffed by Canadian students, one of whom was nice enough to lead us on a tour of the site. The area around the information centre includes a recreated section of trench and a restored tunnel - the Canadians used these tunnels for cover before they advanced on the 9th of April 1917. The tunnel we visited had been expanded and strengthened for visitors, but an unaltered section juts off to the left, giving visitors a view of the conditions in the tunnel on the day of the attack. The trenches are recreated in an artistic way - the sandbags are made of stone, and the trench is shallower and wider than it ought to be - but they give a good impression of a Western Front trench.

After Vimy, we headed a little way down the road, past WWII memorials to the Poles and Czechs, to Notre-Dame-de-Lorette. This is a concentration cemetery for the French dead of the battles around Arras and Artois, and includes both a graveyard and a church. The scale is prodigious - it reminds us that while the war tore a gaping hole in Australia, Britain and Canada, from France it stole a whole generation. The endless crosses are stark enough, but it was the names of the missing inside the church, etched onto the walls, that caught by breath. They’re etched onto the walls like wallpaper - there are names on every wall in every direction. When you sit in the pews here, you are surrounded by the lost legions of France.

There is a foolish idea that French soldiers are cowards, or are bad at war. I’ve seen all the old jokes - ‘French rifle, never fired, once dropped’ and ‘there are trees on the Champs-Elyesses so that the Germans can march in the shade.’ I urge people who believe this to come here, to see the countless crosses and read the countless names, and then see if they can dare accuse them of cowardice.

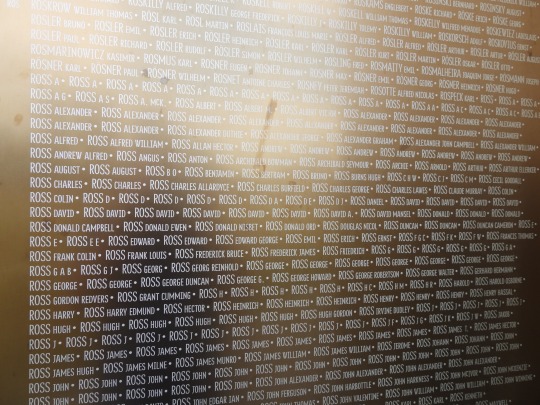

A more recent installation at Notre-Dame-de-Lorette is an enormous ring. Here are listed the names of the dead of the Arras and Artois battles. It disregards country and rank, naming every single person in alphabetical order. One walks around the inside the ring and sees name after name after name. When you reach a common surname, you see a wall of Smiths or Schmitts or Singhs, as if they are the bereaved of some massive family. This was a centenary initiative, put into place by pacifists and historians determined to promote peace and to provide equality in death. It is created with the most noble of intentions in mind.

I utterly despise it.

In my mind, this isn’t equality, this is obliteration. This is the annihilation of the human within a faceless mass. At least at the Menin Gate or at Theipval, the men have a sense of community, even if that community is within battalions and regiments. At least they get the basic dignity of being a part of something. I’m sure to the people who made this memorial, the idea of being identified by a cap badge would be horrifying, and I respect that opinion - but those cap badges meant something beyond military administration; they tied them to homes far away. If you were a 1st Battalion man, you were from New South Wales. If you were from the East Lancashires, you probably came from the west of England. You had a community, a history, some form of distinction. Here you are nothing. Remember how I said Langemarck was obscene? So is this, but it’s worse for me, because at least at Langemarck they got to be Germans. These names don’t even really get to be humans.

I’ve read Siegfried Sassoon’s poem on the Menin Gate - those ‘intolerably nameless names’ - but today I think I get it. These people are deprived of all identity, all personality, all story. You may as well as listed episodes of Seinfeld, or types of compost mixture. I know I’m probably going to make my professor very upset by saying this, because I think he really likes it - as is his right, and I think no less of him for it. But this ring is one of the ugliest things I have ever seen. And I think of the money that went into this - we could have spent it on exhuming and digitising records, telling these stories, giving these men life. Is that not a far better memorial? If you want to make a pacifist statement, tell me who these people were, tell the world of these lives cut short. Show us their faces.

Wilfred Owen said these men died ‘as cattle.’ Why should they be remembered as cattle?

We headed back to Lille after that - our last night here. We head on tomorrow, via Bullecourt and the museum at Peronne, to Amiens. Paris, god help us, looms ahead, but there’s still plenty of frontline to get through first.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

30 June 2023

This Earth

Lille

30 June 2023

In July 1916, as the meatgrinder of the Somme wound on, the British high command looked for methods to divert German troops from that sector of the front. At this stage, the area near Armentières was already soaked in the blood of the BEF - the catastrophic attack at Aubers Ridge on the 9th of May 1915 comes to mind. Now there would be a new attack by Richard Haking’s IX Corps, pushing against the German positions at the town of Fromelles. Two divisions would be involved; the British 61st Division and the newly arrived Australian 5th Division.

Haking’s planning was rushed, and intelligence was poor. Generally, one wants to attack when one outnumbers the enemy by about three to one - at Fromelles, the Australians and British attacked an enemy that outnumbered them two to one. The ground had not been reconnitorered, and the attack required men to advance on a narrow front into German pillboxes and breastworks that covered just about every inch of the flat ground of advance.

The result was an unmitigated military disaster and the elimination of the 5th Division as an effective military unit for a very long time afterwards. The AIF suffered over five thousand casualties and two thousand dead - it remains the bloodiest day in Australian military history.

We departed Ypres early this morning and crossed the border into France, arriving at Le Trou Aid Post near Aubers Ridge around 9am. Most of the graves here are British troops killed either in late 1914 or in the disaster of 9th May 1915, but there are scattered names from later battles, including Australians killed at Fromelles. There is one French soldier mixed in with the British, easily identifiable by the French cross headstone, and in the corner what we believed was an unnamed French civilian. Like Essex Farm, Le Trou was an obvious place for a cemetery, being the place where the wounded were carried to be processed or - more often than not - to die.

A little way down the road from Le Trou was VC Corner. This is one of two wholly Australian cemeteries on the Western Front - the other is somewhere in Flanders - and one of the most stark and brutal of the CWGC’s sites. When the dead were exhumed after the war, not a single man could be identified - their bones had become entangled together, with only the shrapnel of their uniforms to tell that they were Australians. It was decided that it would be too much to have a cemetery filled entirely with headstones reading ‘Known Unto God’ - it would be an obscenity - so the men were reburied in two mass graves, covered by flat stone crosses and squares of roses. The names of the missing of Fromelles were engraved at the back of the cemetery, behind the Cross of Sacrifice. There are 410 men here, of 1299 missing altogether.

It was here that I finally got that opportunity to read Wilfred Owen’s Anthem for Doomed Youth that I’d been angling for. I think my professor was a little hesitant to let me, but afterwards he agreed that this was the best place to read it.

Between VC Corner and the modern Digger Memorial is what was No Man’s Land, and few poorer places for a general advance I have ever seen. It is a perfect killing ground - especially in 1916, when the concept of the creeping barrage and combined arms were in their infancy. Many of the bunkers are still there, albeit mostly decrepit - some enterprising farmers preserved trenches and fortifications after the war, knowing they could make a quick franc off of British tourists in the area. The Digger Memorial is a recent installation, erected during the centenary - it depicts an Australian soldier carrying a wounded comrade, and it faces back towards Australian lines. It’s a poignant piece, but it’s a bit of an example of selective memory. In some parts of the line, the Germans allowed this, but in others they used wounded men as bait to draw others into their fire. It all depended on who was in charge and the character of the unit, and I’d be dishonest if I said the Allies never did it too, but the memorial is a conscious choice to focus on remembering compassion rather than killing. This is a good thing, but it’s always good to have a pesky historian around to remind you that war is fundamentally a violent affair.

We proceeded from there into Fromelles itself, although we went to the museum just outside the town rather than the town itself (not that Fromelles is particularly large.) The museum is recent, for a reason we’re about to get into, and it’s a fairly small and simple affair. It resembles a lot of French museums I’ve seen - the French love their mannequins, even if some look a little disconcerting. It’s a good primer to the battle, so if you’ve never visited the site I’d recommend it. It ends with the story of the recovery of the dead - not in the early 1920s, but in the early 21st century.

I have met Lambis Englezos, and I want you to understand that I mean this in the most affectionate way possible. Like most people who make history, he’s absolutely insane. In the 2000s, Lambis carried out extensive research and posited that a mass grave existed at Pheasant Wood near Fromelles. He worked this out through a number of primary sources - perhaps most notably, looking at the old German light railway lines behind their front, and aerial photographs from the summer of 1916. His ideas weren’t taken entirely seriously by historians, and there was a hesitancy to dig. It’s hard to blame them - here was this oddball, who didn’t even have a degree never mind a doctorate, proposing to dig up a wood in France to find bodies the Australian government had given up on in 1924. Lambis persisted - in 2007, the government commissioned a geological survey that found out that he could well be right, and in 2008 he was allowed to dig. His team found 250 bodies, mostly Australian but a few British, and for the first time in fifty years, the CWGC was tasked with building them a cemetery.

Pheasant Wood Cemetery is the result, and it’s one of the most poignant cemeteries on the Western Front. All other cemeteries record on their epitaphs the words of a lost generation; here, the worlds are ours. There remain the exaltations of sacrifice and giving one’s life for another - and there’s nothing wrong with that, I must add - but among them are reminders of communities, memorials to parents and siblings long past, even nods to how commemoration has evolved since 1918. Wilfred Owen is quoted - even if, thanks to the guidelines of the CWGC, it’s not one of his more condemnatory verses - as is Eric Bogle. Yet for all of this, there’s a sense of disconnection. There’s comfort in calling these deaths sacrifice, in saying they laid their life down for mates or country or king - but from my historian’s perspective, I think this battle was a total waste of human life, not so much a sacrifice but an act of murder by incompetence. Of course, the CWGC would never let you say that on an epitaph, but I think some people found their own ways to get past the censors. One particularly stark one was that of Private J. R. Smith, 31st Battalion. His grave has no cross, just a stark white space between the date of his death and his epitaph.

‘This Earth, his final peace.’

Sometimes the most simple language is the best.

We left Fromelles for Neuve-Chapelle. Neuve-Chapelle was attacked in March 1915 by Canadian, British and Indian troops - it is here that the latter are commemorated. Hindus and Sikhs are cremated after death, and as a result you will not find many in a CWGC cemetery. Instead, their names are listed here - nearly 5000 died on the Western Front. (All in all, at least 74,000 Indians died during ther Great War.) The First World War sits awkwardly in Indian history - the British Indian Army was entirely voluntary, and Indians went to fight because they fought war an honourable, or because they genuinely believed in the cause and were loyal to the Empire, or because it was simply a job and a roof over one’s head. Many supported the war because they believed Indian participation would coax the British into allowing them greater independence, perhaps as a dominion - a lawyer named Mohandas Gandhi being one of them. Instead, they were rewarded with great repression after the war, including the inexcusable and hideous massacre at Amritsar. The combination of the failure of Britain to adequately acknowledge the Indian participation in the war, and the piles and piles of dead bodies at the Jallianwala Bagh (and other places) put paid forever to the idea of peaceful Indian independence within the British Empire. The seeds of the Indian Independence Movement - and Partition - were planted in this war.

Nearby is the memorial and cemetery of the Portuguese Expeditionary Corps, or CEP. The CEP had a bad war - it was absolutely smashed at the Battle of the Lys in April 1918, with a third of its force killed, wounded or (overwhelmingly) taken prisoner by the Germans. This is not to say that the Portuguese were not brave nor good soldiers - the Peninuslar War a hundred years earlier is testiment that they were - but they were not at all prepared for the Western Front, to say nothing of the hurricane bombardments and stormtrooper attacks of the German Spring Offensive. We didn’t go into the cemetery, but it felt remiss not to mention it.

We entered Lille, and that ended the day. I had an early lunch - the first McDonalds I’ve had in what feels like ages, to be completely honest - and settled in to write this. Now, France is currently participating in it’s favourite pasttime, that being rioting, but I feel fairly comfortable and safe where I am, so don’t worry too much about me - and tomorrow we’ll be fairly rural, heading down to the Arras sector of the line.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

29 June 2023

The Monstrous Anger

Ypres

29 June 2023

Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae, a Canadian medical doctor, is probably one of, if the not the most misunderstood of the so-called ‘war poets.’ He is the author of the famous poem ‘In Flanders Fields,’ which might be the single most prolific piece of war poetry ever written. He penned it on the back of a field ambulance the day after he’d had to bury a close friend. He himself died of pnumonia in 1918, which only adds to the poignancy of the poem. It has been read in memorial services, in schools, at war memorials and museums and cemetaries.

His words are iconic - that stanza, ‘we are the dead,’ etched itself into the minds of generations. Those first two verses are so powerful that they have blinded people from the poem’s true meaning, expressed in the final verse.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

There you have it. This most iconic and powerful pieces of prose, repeated by the mournful generations that followed that First World War, was intended to inspire men to go to war.

I do not consider John McCrae to be an evil man - he was of his time, and sincerely believed in the justice of his cause - hell, had I lived in his time, I might have agreed with him (and even today, I have very little sympathy for the German cause.) But I do consider In Flanders Fields to be an evil poem, a profoundly evil poem, because it not only inspired men to go to their deaths in Flanders and France, but it was used as a potent tool in the Borden government’s campaign to introduce conscription to Canada. I am not saying we should not recite this poem, but I am saying that we should think more carefully about what it really says.

McCrea isn’t buried in Flanders, but he’s commemorated here at Essex Farm Casualty Clearing Station, where the men he treated were buried. This was where we began today - the bunker in which the Canadian-run station was run remains on the site, and tributes are still left inside. Yet it’s not only the Canadians who have claim to this land - the 49th West Riding Division has its memorial obelisk here, and the cemetery is littered with the dead of the Yorkshire regiments that formed it. It’s a reminder that men often didn’t die instantly on the front line - they lingered, in ‘casualty clearing stations’ like this, often for days, until death finally claimed them. Some of them even suffered the final indignity of being looted by some of the more unscrupulous oderlies - the acronym of the Royal Army Medical Corps, RAMC, was sardinically corrupted by British troops into ‘Rob All My Comrades.’ (The British had a knack for this - NYD (‘Not Yet Diagnosed’) signs above medical cases became ‘Not Yet Dead.’)

After Essex Farm, we entered Poperinge, which is a lovely town which I absolutely do not recommend visiting until they find out where that open sewer smell is coming from. (Perhaps they are trying to emulate the smell of frontline latrines?) Odour aside, there’s a fine Belgian memorial outside the cathedral there, but we were most interested in the Execution Post. There were dozens of these on all fronts - the Italians in particular were very profligate when it came to shooting their own men. In Poperinge, the execution site was outside the town hall, and today is a memorial to the men killed by their own side.

Men were, of course, shot for serious crimes - murder and rape were capital offenses. For the most part, however, they were shot for desertion, for refusing to fight, for dropping their weapons in the line of duty - essentially, for cowardice. Today, we know that soldiers can and do reach their limit, and that they need to be treated in compassion, but in 1917, PTSD wasn’t understood, and a man having a trauma induced panic attack could find himself judicially murdered by unsympathetic courts martial. Elsewhere, particularly in Italy, executable offensives could be truly absurd. One man was shot for failing to remove his pipe from his mouth when saluting. Other men from ‘underperforming’ units were shot at random to encourage the others - a revival of the Roman practice of decimation. It was not only the battlefield that could be pitiless.

We departed Poperinge and headed to Hill 60. Hill 60 was actually one of two points on one hill - the north was called ‘Hill 60’ while the southern portion was called ‘the Caterpillar.’ I say it ‘was’ one of these points, because Hill 60 and the Caterpillar are no longer there. Although this portion of the line was not on the Messines Ridge, it was attacked as part of General Herbert Plumer’s attack on the ridge in June 1917. Prior to the attack, tunnellers - famously the 1st Australian Tunneling Company, but also Canadian and British miners at various points - dug beneath German lines and planted massive mines beneath their strongpoints. On the 7th of June 1917, they were detonated. Hill 60, the Caterpillar and ten thousand German lives were extinguished in a pair of colossal explosions - just two of nineteen exploded that day. The assault that followed was a example of an unqualified British success - but the opening of the Third Battle of Ypres shortly after prevented much exploitation.

The craters remain, covered in grass, trees and water, but clearly visible as a scar upon the land. To see the sheer size of the crater at the Caterpillar, and to contemplate the sheer destructive power that caused it, is truly a sobering thing. This, effectively, is the grave of thousands of men - not that anything remained to be found after the mines went off. At very least, I suppose, it would have been quick.

We returned to Ypres for a quick lunch, and then headed back out to Tyne Cot Cemetery, where lie the dead of the late stages of the Passchendaele battles. This is the largest Commonwealth cemetery anywhere in the world, with 13,000 men interred within - a smaller number than Langemarck, but it must be remembered that the vast majority of them have individual graves or headstones. We were guided through by a CWGC intern, shown a few particular graves, and talked through the process of maintaining a cemetery and working for the CWGC.

Tyne Cot is so large that it is numbing. I remember staring at the endless rows of dead - 8000 of them are unknowns, and whole rows can consist of ‘Known Unto God’ repeated ad nauseum. The numberless dehumanised ‘blank’ graves, broken occasionally by one with a name and an epitaph, put me in the mind of old pictures of units before and after major battles - a full parade ground before, a few dozen men afterwards. It made me think of one of those dark trench songs - ‘if you want the old battalion, I know where they are. They’re hanging on the old barbed wire.’

We moved on from Tyne Cot to the Flanders Field American Cemetery. In the last few months of the war, two American divisions - initially the 27th and 30th Divisions, then the 37th and 91st Divisions - fought under British and Belgian command in the last battles around Ypres and the Lys. This was contrary to General John Pershing, the American commander’s, belief that Americans ought to fight under their own command in their own units (a policy that, alongside Pershing’s complete refusal to take advice from the British and the French, led to proportionately higher casualties amongst US forces.) I’m not quite sure why the Americans let these divisions fight with the other Allies, but my guess is that they politically felt they ought to be shown to be fighting in Belgium.