Text

The best of Worth

By Ronald Bryden

The Observer, 12 November 1967

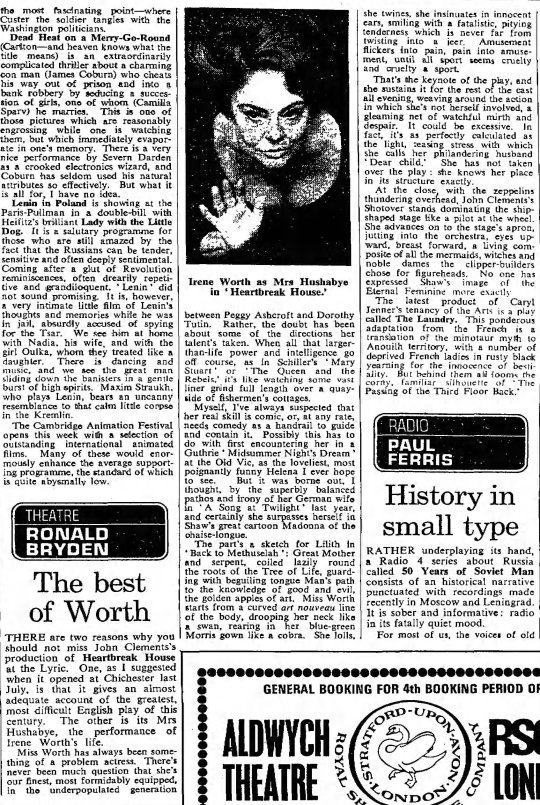

There are two reasons why you should not miss John Clements's production of Heartbreak House at the Lyric. One, as I suggested when it opened at Chichester last July, is that it gives an almost adequate account of the greatest, most difficult English play of this century. The other is its Mrs Hushabye, the performance of Irene Worth's life. Miss Worth has always been something of a problem actress. There's never been much question that she's our finest, most formidably equipped, in the underpopulated generation between Peggy Ashcroft and Dorothy Tutin. Rather, the doubt has been about some of the directions her talent's taken. When all that larger-than-life power and intelligence go off course, as in Schiller's 'Mary Stuart' or 'The Queen and the Rebels,' it's like watching some vast liner grind full length over a quayside of fishermen's cottages.

Myself, I've always suspected that her real skill is comic, or, at any rate, needs comedy as a handrail to guide and contain it. Possibly this has to do with first encountering her in a Guthrie 'Midsummer Night's Dream' at the Old Vic, as the loveliest, most poignantly funny Helena I ever hope to see. But it was borne out, I thought, by the superbly balanced pathos and irony of her German wife in 'A Song at Twilight' last year, and certainly she surpasses herself in Shaw's great cartoon Madonna of the chaise-longue.

The part's a sketch for Lilith in 'Back to Methuselah': Great Mother and serpent, coiled lazily round the roots of the Tree of Life, guarding with beguiling tongue Man's path to the knowledge of good and evil, the golden apples of art. Miss Worth starts from a curved art nouveau line of the body, drooping her neck like a swan, rearing in her blue-green Morris gown like a cobra. She lolls, she twines, she insinuates in innocent ears, smiling with a fatalistic, pitying tenderness which is never far from twisting into a jeer. Amusement flickers into pain, pain into amusement, until all sport seems cruelty and cruelty a sport. That's the keynote of the play, and she sustains it for the rest of the cast all evening, weaving around the action in which she's not herself involved, a gleaming net of watchful mirth and despair. It could be excessive. In fact, it's as perfectly calculated as the light, teasing stress with which she calls her philandering husband 'Dear child.' She has not taken over the play: she knows her place in its structure exactly.

At the close with the Zeppelins thundering overhead, John Clements's Shotover stands dominating the ship-shaped stage like a pilot at the wheel. She advances on to the stage's apron, jutting into the orchestra, eyes upward, breast forward, a living composite of all the mermaids, witches and noble dames the clipper-builders chose for figureheads. No one has expressed Shaw's image of the Eternal Feminine more exactly.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Frank Marcus's Notes On His Love Affair

By Frank Marcus

Plays & Players Magazine, July 1972

THE WRITING OF IT WAS THE EASIEST PART. I took as my text Robert Frost's 'You don't take notes during a love affair', amplified in Dora's opening speech with a quote from V S Pritchett's auto-biography. Cyril Connolly's words (on Thomas Mann) would have served equally well: '... one must be content to remain an observer of life and of one's own life, often deprived of the experiences which render more rounded and full those of other human beings.'

The tragi-comical predicaments of a writer's life (any writer's life), not untinged perhaps with a degree of self-disgust, were naturally close to me, and the creative pot was kept effortlessly on the due us is dices lie weeks it look to write the plastlessly end product—as is often the case with me was inordinately long but all of it seemed to me essential.

The character of Dora I modelled closely on the artistic persona of the great Swiss actress Maria Becker, and I hoped I might lure her to London. Hence the original Dora was given a German origin and there was a flashback scene, just before her final destructive rage, which showed Jim rescuing her from the post war holocaust, with both of them embodying a spirit of vouth, passion, and untainted love. In Ronald Bryden's opinion. the fact of my own German origin gave these scenes a deeper and integral significance.

As is my usual practice, the completed script was shown first to a varied kind of panel of readers (friends, but by no means sychophants) and their reactions were overwhelmingly favourable.

Not so the managements. The play's length, added to my wish to import an actress totally unknown in England, brought a sheaf of rejections. My stated willingness to make cuts, preferably in cooperation with the director, made little difference. The script gathered dust, and was shown occasionally to friends in the theatre. As these included actresses, I made the mistake of forgetting that they would assume I was offering them a part in the play. I shall not make that particular mistake again.

At this time—roughly a year ago—the impresario Marvin Liebman made some tentative moves to bring the immensely successful revival of my earlier play, The Formation Dancers, given at the Hampstead Theatre Club, to the West End. When these plans collapsed, he read my new play, liked it, and showed it to Robin Phillips. Robin reacted positively, and for the first time the project showed signs of getting off the ground.

The organisation of the German theatre, which compels actors to plan as long as two years ahead (and in the process turns them into civil servants), ruled out Maria Becker. To my mind, the only English actress with the necessary quality for Dora was Irene Worth.

Irene had just returned after a year with Peter Brook's experimental company in Paris and Persia. I handed her the script with trembling hands in the foyer of the Cambridge on the first night of West of Suez and watched her with horror starting to read it, sitting alone in the auditorium during the interval. I should add that, by now, I had cut more than 500 lines of dialogue from the play and reduced it to manageable proportions.

She studied the text with enormous care—in fact, she took herself off to Aldeburgh for a week to do so. She returned with six pages of notes, and I can honestly say that they were among the most stimulating, challenging, and intelligent comments any play of mine has received.

I assented to nearly all her suggestions for alterations. The only point of contention concerned the status of Dora as a writer. I had meant her to be a competent but run-of-the-mill novelist; I didn't want her to have the alibi of genius. It's easy (posthumously) to forgive the outrageous behaviour of a Strindberg or a Rimbaud, and Ibsen, Tolstoy, and Joyce—among many others—regarded their lives with icy disillusion. Irene wanted to use Dora to convey some of her own thoughts and emotions. With a star of that magnitude you don't argue, you comply. I rewrote totally the opening cadenza and tried to accommodate Irene's wishes as best I could. The original Dora was imprisoned in her room and addressed an imaginary audience: Irene stretched out her hands.

The rest followed smoothly. Nigel Davenport was Irene's first choice for Jim: we all concurred and were delighted when he accepted. Contrary to speculation, Jennie was not written for Julia Foster. I had written a play for her, shortly after she appeared in my first television play in 1966. It was called Studies of the Nude, produced at Hampstead, but Julia—alas—was held up on a film and could not play in it. I shall never cease to regret it. Ever since, I have been acting as her career adviser (unpaid). I implored her to go after Lulu and thought that Jennie in Notes, who is the exact opposite of the theatre's greatest sex symbol, might enable her to demonstrate her versatility as an actress.

As is my custom, I stayed away from the early rehearsals. When I rejoined them, I was struck by Robin's brilliant and unorthodox methods, but sensed that the tremendous rapport between him and Irene, which had proved so successful with the RCS's Tiny Alice, was somehow lacking. Marvin Liebman, as ever the epitome of kindness and generosity, hovered in the background, giving us total artistic freedom. Dora, by the way, had by now become English and the flashback scene, while retaining some of its intensity, had been transposed to a house near an airfield during the Battle of Britain. We tried it during our first week out-of-town in Southsea, but decided to cut it. as it came too late and seemed redundant.

Our second (and final) try-out week was in Brighton: a notoriously unreliable venue for a new play. We were triumphant. By the end of the week performances were sold out; the actors were cheered; the press was wonderful. The resident theatrical contingent turned out in force and were most complimentary. I was particularly pleased by a personal letter from T C Worsley: until his retirement a few years ago one of the most respected theatre critics in London. He wrote: 'Just a line to tell you how much I both enjoyed and admired your play on Saturday. It has great ingenuity, great elegance of form, and much human feeling. And how delightful for once to see a play that is really written and neatly constructed. I don't see how it can fail to be a great success: it certainly deserves to be.'

After the first night in Brighton, we were offered the Globe, and we returned to London confident, if not euphoric.

The two preview performances were also encouraging. I should like to believe that it was not accidental that the three critics who attended a preview as well as the opening night responded to the play with enthusiasm.

On the first night, I sat in a box, well hidden behind a curtain. The audience looked fashionable, a trifle elderly, with a sprinkling of ageing film stars. That curious and (I had hoped) defunct phenomenon, a West End audience, had descended on my play, hoping to see—I should guess—an amusing Shaftesbury Avenue comedy. Neil Simon would have served them excellently.

I knew within seconds that the play was misfiring. I'm not searching for alibis, but this audience refused to 'meet' the play. They sat back, elegantly attired, daring the actors to entertain them. The evening was not a calamity, but it was equally clearly not a smash hit.

In the circumstances, the notices were better than expected. The critics were split clean down the middle; there was praise as well as stricture. I was saddened only by Irving Wardle, who failed totally to connect with the play, mistook parody for imitation (Anouilh), and credited the deliberate clichés to me instead of to the characters who uttered them (ditto Jim's lame attempts at epigrams).

The experience certainly put paid to the myth that dog doesn't eat dog. There were examples of venom, a gleeful desire to insert the knife where it hurts and, in one case, near-libellous innuendo. As a practising theatre critic, I can't say that I was surprised.

Irene Worth bore the brunt of the attack. Her fortitude and kindness to her fellow actors increased my huge admiration for her. But, far more significantly, she proceeded to develop her performance, turning each occasion into a 'happening'. With Irene Worth in the cast, no play could be less than vibrantly alive. I'm glad to say that it didn't take long before she received the praise that she deserved.

As for myself, I have once again been privileged to see my fantasy embodied on the stage. I can proceed now to new fan-tasies. Irrespective of applause or abuse, there is only one road open to me. It leads back to the typewriter.

#irene worth#nigel davenport#julia foster#articles#notes on a love affair#frank marcus#plays & players#1972

0 notes

Text

'My Dear, Put Back the Words'

Let Albee explain Albee. In 'Lady from Dubuque,' Irene Worth listens for the poetry.

By Harry Haun

Daily News, January 27, 1980.

Irene Worth, the "international actress" from Omaha, sits in a back corner of Gallagher's, dealing with the specialty of the day (corned beef and cabbage), looking resplendently inconspicuous in her Anyone face.

Save for the fact that she's surrounded by press and publicists, she could pass for anyone and, indeed, has during her 38-year life in the theater. Most recently she has been, by stage turns: a sensuous Hollywood siren on the skids (Tennessee Williams "Sweet Bird of Youth"); a destitute Russian; dowager (Anton Chekov's "The Cherry Orchard"); an indefatigable survivor sinking slowly into a mound of earth (Samuel Beckett's "Happy Days").

Now, she is "The Lady From Dubuque" in the so-named Edward Albee play opening Thursday at the Morosco. The character carries cryptic overtones like a flag, which is inevitable with Albee and par for his pre-premiere course. Everyone con nected with the production seems to have taken the blood oath of secrecy, and all the author will allow is that the title comes from a remark Harold Ross once made about the market for The New Yorker: "It won't be written for the little old lady from Dubuque." The same, of course, could be said for any Albee play.

For the present, his secret is safe with Irene Worth. True to the show's team-spirit, she will only admit to the title role. Period. "I'm not going to talk about what Edward's plays are about because it's too difficult," she declares out front. "Edward is the authority on his plays. He's got to tell what his plays are about. I'm just going to be in them." She makes no secret, however, of the fact that she is reveling in returning to Broadway in an original work—for her, the first time this has happened since "Tiny Alice" 15 years ago; now, as then, the author is Albee, the director is Alan Schneider and the producer is Richard Barr. "We have sort of an old scene going together," she allows.

"I love working on this play and working with Alan. Edward comes occasionally, and we all work together and change if we have to. I find it the deepest, best kind of work, very stimulating and energizing. It rivets one's concentration. It's like realizing the dream of being an actor because you're immersed in the text and exploring how you reveal it.

"Recently, Edward took out two words, and I'm going to ask him today to put them back—or two other words—because I need them to complete the poetry in that line. He's a very great musician, you know, so he's not unaware at all of rhythm and balance and dynamics. The mastery of his writing is that this is not imposed. The audience is not aware of it. It's only that the lines fall comfortably to the ear. There's an unselfconscious musicality in his writing."

When Irene Worth talks shop—and she never talks anything else to interviewers—the passion shows. It gives her a beauty and energy that belie her 63 years, for acting is something she knows, and loves, and this feeling has been returned to her in italics. To date, she has collected two Tonys (for "Tiny Alice" and "Sweet Bird of Youth"), one British Oscar (for 1958's "Orders To Kill") and the most extravagant praise imaginable. Walter Kerr, reviewing her "Hedda Gabler" In Canada 10 years ago, suggested that she "is, quite possibly, the best actress in the world." The road that has brought her to this point in time back to Broadway has been anything but a straight line. Indeed, if charted, her career could make, the course of pinball seem planned. Yet, miraculously, the moves have been right ones. She left Omaha as a child when her school-superintendent father accepted a comparable post in Los Angeles. She received a degree in education at the University of California and taught kindergarten for two years before heeding her muses. When 15 years of training to sing at the Met came to naught, she settled for the stage, surfacing first in 1942 in a road company of "Escape Me Never" and the following year on Broadway in "The Two Mrs. Carrolls," in both instances supporting Elisabeth Bergner. It was Bergner who pointed her toward the British theater where she toiled productively for the next 30 years, save for occasional New York forays in plays like T. S. Eliot's "The Cocktail Party," Friedrich Schiller's "Mary Stuart" and Lillian Hellman's "Toys in the Attic." From the English, the actress acquired classic training, an awesome "international" reputation and an extra syllable on her first name (it's pronounced "I-ren-ee"). Since her engagement in "Sweet Bird of Youth" a few years ago, Manhattan has been her home.

"It's my choice, I think," she says, pondering the path above. "I like to grow as an actor. Also, I don't want to work on bad material. It's a waste of energy. If you're in a good play, the writing sustains you and ieeds you ana nourishes you, and you can get through the evening and have self-respect It's so thrilling if you've really done the play that night and it was good and you got somewhere."

Considering where she has gotten, it's slightly superfluous to wish her good luck as "The Lady From Dubuque," but she smiles anyway. "My dear, the only good luck you can have is enough rehearsal time so you get it right."

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Irene as Lyubov Ranevskaya in The Cherry Orchard, 1977 📸 by George E. Joseph.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Beaton’s View: Number One Irene Worth

By Cecil Beaton

Plays & Players Magazine, January 1972

That such an actress as Irene Worth, with her depth and freedom of expression and dazzling intelligence, should not be cherished as one of the greatest ornaments to the English stage is a murky mystery. Clive Barnes has written of her as ‘one of the most illuminating actresses of the English-speaking theatre’, while Walter Kerr has it that she ‘is just possibly the best actress in the world’. Ronald Bryden considered ‘no-one has expressed Shaw’s image of the Eternal Feminine more exactly’; and Peter Roberts ‘her exceedingly glamorous and effortlessly commanding Mrs. Hushabye…she seems to take Shaw’s dialogue on the palm of her hand and blow it out into the auditorium like a feather’.

Although London is her home, English audiences see her seldom. It is iniquitous that she has played only less than fifty performances at our National Theatre since Olivier became its head. We are parched for wonderful performances in wonderful plays, and since we are so short on great leading ladies, why have we been deprived of seeing Irene Worth as Hedda, or as Silia Gala in The Rules of the Game? Why has she not been given the opportunity to play Ibsen, Turgenev, or Chekhov? Wouldn’t it be exciting if, under a different director, the new National Theatre building, scheduled for 1973, should be inaugurated with Irene Worth playing Cleopatra? She alone with her imagination and originality, her extraordinary range of voice, her strength, her powers if projection could do justice to the infinite varieties of seduction necessary for this most difficult of roles.

Other theatrical managements without a thought but for the weekly receipts have whined: ‘Is she “Box Office”?’ But how can any actress become ‘Box Office’ if she is rarely seen? Some have complained that she is difficult. Most creative artists are invariably difficult, but that is surely an irrelevance. All that matters is the performance. No doubt Bernhardt was difficult.

In fact Irene Worth is not difficult. She is a perfectionist. She wishes anything with which she is involved to be under the best auspices. Once she has made up her mind to dedicate herself to creating a new role, she is totally professional. Although she trusts that the director will ‘allow the yeast to make a good loaf’, she will take his instructions implicitly even if she feels instinctively that he is at times at fault. Before the active preparations for each production she finds time to do a connoisseur’s research, reading all possible relevant books on the subject, visiting museums, and limbering up in gymnasiums and taking fencing lessons. If the play is a period one, in order to get the feel and the stance necessary to wear the clothes, not only does she study all possible pictorial documents of the epoch, but entices museum curators to bring out their costumes so that she can learn the cut and feel the texture of the stuffs.

It was when, at Swiss Cottage, Irene Worth gave grace and distinction to a tiresome war-play by Virginia Cowles and Martha Gellhorn that I knew here was a rare theatre newcomer. In the original production of The Cocktail Party in New York she had the opportunity to show her unique talent as a speaker of prose-poetry. Although she was acclaimed by all the critics, when the play came to London she was not at first in the cast. Another New York success in Schiller’s Mary Stuart brought her to the Old Vic in a translation by Stephen Spender. In The Queen and the Rebels by Ugo Betti, and translated for her by Henry Reed, she showed herself star stuff. In Durrenmatt’s Physicists, even in a part so alien to her as that of the hunchback Swiss doctor, to quote a critic ‘she could take a role and wrap it around her own soul’. In the Coward plays Suite in Three Keys she played three parts of complete diversity, and as the brash, blue-haired American her sense of comedy and caricature was astonishing. In Heartbreak House she made Dame Edith’s earlier Mrs. Hushabye seem a mere sketch for the part in comparison to the extremely rich portrait she created. By the sheer force of her personality, and her physical prowess she gave a cohesion to the entire production of Brook’s Oedipus.

She has not appeared on the London stage since returning over a year ago from Ontario where the critics wrote: ‘The big things she does in Hedda are staggering in their arrogance and the authority with which that arrogance is supported.’ ‘The fires of her intelligence are burning all the time.’

Irene Worth is a dedicated player who will sacrifice comfort or salary to appear in interesting plays as, when Coventry was still a ruined city, she worked with the Repertory in a rickety old barn, or travelled miles by bus to distant theatres. She will willingly perform in a tent—as she did at the inauguration of the Stratford Theatre in Ontario—if she considers the project worthwhile. She will gladly endure the winter cold of Finland or Russia, the dust storms and summer heat of Persepolis, if she considers that she is learning something that will be valuable to her career. ‘The best academy is experience,’ she says.

Irene Worth is one of the rare intellectual actresses. She started life as a kindergarten teacher with a degree in education. Then she trained as a pianist, and her love of music has never left her. She can speak several languages, has a great knowledge of literature, and her vistas of interest and taste stretch far in many directions. These attributes only add to her mien, and when she comes on stage the audience knows it is in the presence of someone quite special. Irene Worth has a quality that can make pigmies of others. Thespians jealousies and pettinesses are outside her range, but when she is deceived by others with motives less lofty than her own, she is sadly shocked. She is herself most generous to her fellow performers, and considers that actors should performs for the others in the cast and not for the audience. The stars with whom she has an affinity are Scofield, Gielgud, Finney, and David Warner, (‘Acting with him is like swimming in silk’).

From the performances she has already given we know how well she could play Pinter, Beckett (Happy Days in particular), Wilde and Pirandello. It would be good to see her as The Second Mrs. Tanqueray or raise the standard of musicals. (She is in excellent voice just now.) But while still hoping for these opportunities we must content ourselves that she is to appear next spring in a new play by Frank Marcus, Notes on a Love Affair, directed by the brilliant young Robin Phillips. If no suitable offer arrives for her to prove an unassailable position in the great classics, then she must be goaded to become her own manager, run her own repertoire, and show what greatness she has attained in the height of her maturity. It might well be that, by so doing, she would not only show herself again to be invincible as a great actress, but also become the enlightened theatrical impresario that the London stage at the moment so sadly lacks.

0 notes