Note

Where are the people who abused the black and white students at woolworth lunch counters in the 50's and 60's. Have any repented publicly

Good question. I was able to find and interview one of the high school students who was part of the melee and whose image was captured in the iconic photo of that scene. He never repented and, indeed, seemed to believe that he was one of the heroes that day for fighting to preserve the ‘Southern Way of Life.’ I spoke to him once again after the book came out (and only a few months before his death) and he expressed no remorse, continuing to believe that segregation was a better way for the races to co-exist. He was particularly opposed to Inter-racial marriage.

You can hear more about my interaction w/ this student on my recent appearance on “The Uncomfortable Truth” podcast: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/the-jackson-woolworths-sit-in-a-discussion-with-mike-obrien/id1498323248?i=1000533861874

#The Uncomfortable Truth#Jackson Woolworth's Sit-In#We Shall Not Be Moved#Loki Mulholland#D.C. Sullivan

0 notes

Text

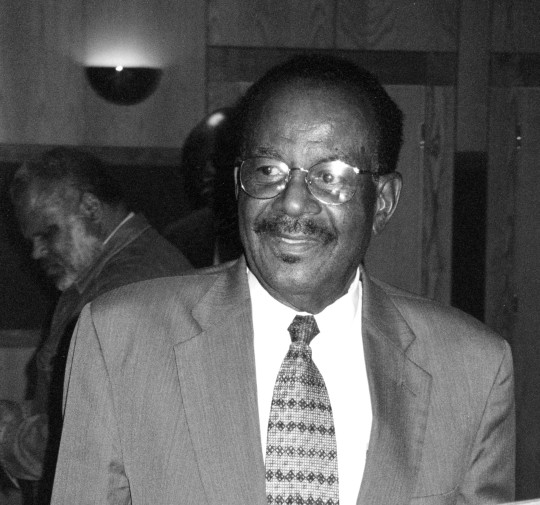

Appreciation - Meredith C. Anding, Jr. (1941 – 2021) and the Tougaloo Nine

Upon first meeting, many a visitor may have been tempted to consider Meredith Coleman Anding, Jr., a reticent, almost opaque, man. Soft spoken, terse yet amiable, sphinxlike, enigmatic. Instead, he was the epitome of John Wayne’s character in The Quiet Man—with a preternatural calm on the surface, but with a fierce, almost primal determination to get what was his due: freedom and the respect that came with it. For this, he will be remembered down through the ages.

For it is Meredith Anding’s name, thanks to its alphabetical primacy, that leads the list of quiet Mississippi freedom fighters that we now know as the Tougaloo Nine. These courageous (and, by their own later admission, a bit naive) college students from nearby Tougaloo College, “stepped into history” (as Tougaloo’s former President Beverly Hogan often said of them) on Monday morning, March 27, 1961, when they calmly entered the Whites-only municipal library in downtown Jackson, Mississippi. It was the first student-led civil rights demonstration in the state, all the more remarkable because it was carried off in the Magnolia State’s capital city, under the noses of the most powerful White supremacist politicians, police force, and spy agency in the country and in an environment of intense racial segregation that had been hardening ever since the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954.

Meredith Anding’s Tougaloo Nine mug shot on 3/27/1961. [Courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History (MDAH)]

Secretly assisted and urged on by the NAACP’s “Man in Mississippi,” Medgar Evers, Anding and his cohort created shock waves of horror throughout the White community by the simple act of entering a library, selecting books from the shelves, and calmly sitting down to read. Their actions made a mockery of Jackson’s Mayor, Allen C. Thompson, who as President of the American Municipal Association had gone on a nationwide tour to tout his city’s racial amity despite its harsh segregationist strictures.

For their crime, Anding and his four male and four female colleagues were arrested for “Breach of Peace”—a newly coined law in many Southern states that allowed police to intervene if individuals were creating a situation that put someone’s peace of mind in jeopardy. When the police first arrived, they tried to persuade the students to leave on their own volition, hoping to avoid a showdown in court. But Meredith and his fellow Tougalooans ignored the pleas of the cops. Once told they were under arrest, however, all of them stood and began to march out to the waiting police cars, ignoring the police and the rowdy crowd that had gathered to sneer and shout racial epithets at them.

All Tougaloo Nine participants posed for a celebratory photo once safely back on campus. Pictured from l-r: Joseph Jackson, Geraldine Edwards, James (Sam) Bradford, Evelyn Pierce, Albert Lassiter, Ethel Sawyer, Meredith Anding, Janice Jackson, Alfred Cook. [Signed photo courtesy of MDAH]

This coordinated action ensured that the group would not be charged with resisting arrest and instead their case would be appealed by the NAACP all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court, testing the validity of such “breach of peace” statutes. Although the case was thrown out on a technicality, nevertheless, the Tougaloo Nine, Meredith Anding among them, would forever stand in dramatic opposition to the false narrative of White Mississippi perpetrated by Thompson and others that “all of our nigras are happy.” Two months later, the Freedom Rides would come to Mississippi and the state would become ground zero for the Movement for Black Equality.

Meredith C. Anding, Jr., was born in 1941 in the small enclave of Myles, Mississippi, about 40 miles southwest of Jackson. The first-born of the Adings lived among extended family for a few years, where he was dubbed with the nickname “Junior Man.” His parents moved to the state capital when Meredith was just five years old. He attended a variety of segregated schools in Jackson, including Adams Economy—a small church school—Sally Reynolds Elementary, and Isable Middle School, and graduated from Jim Hill High School in 1958. Anding attended Jackson State College, not far from his family’s home, for one year and then transferred to Tougaloo in the fall of 1959 to begin his sophomore year.

Meredith’s civil rights bona fides were something of a family affair. Though his mother Nellie was unassuming and reserved—a trait the quiet Junior Man adopted—her sister, Meredith’s aunt A.M.E. Logan, was a forceful personality who involved herself in every conceivable method of citizen activism throughout the 1950s and 1960s. When the Jackson Branch of the NAACP reconstituted itself in the late 1950s after a long period of dormancy, Logan served as the elected secretary of the group and went door to door, even while pregnant, to drum up new members for what was considered by most White Mississippians as a radical Communist agitation group. Later she served as the chapter’s hospitality chair, welcoming various dignitaries—including the Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King, Jr.—to her home. Anding, who lived nearby, was present at many early Mississippi civil rights gatherings.

Meredith Anding pointing to his image in a floor-to-ceiling mural of the Tougaloo Nine leaving the Jackson Municipal Library with police escort. The mural was installed in the Bennie G. Thompson Academic and Civil Rights Research Center on Tougaloo College Campus. [Photo: M.J. O’Brien]

It was Anding’s father, impressed with his sister-in-law’s activism, who signed young Meredith and his sister up for membership in the newly forming West Jackson Youth Council, the youth arm of the NAACP. The group would meet at the Masonic Temple on Lynch Street in the conference room adjacent to the office of Mississippi’s civil rights leader. “Medgar would come over and talk to us every meeting when he was around,” Anding recalled in an oral history interview. As for his own budding role, Anding saw his participation “as kind of a duty,” he said. “I felt obligated to go to meetings and to participate because most of the kids my age weren’t willing to.”

The young activist benefitted from his closeness with both his aunt and with Evers. On several occasions he was chosen to represent the West Jackson Youth Council at gatherings of NAACP youth from throughout the South. It was at these sessions that he became aware of the possibilities that real activism held. “Most other kids from other states had already participated in some kind of protest activities,” he recalled. “It was there that we started thinking, ‘OK, we really have to do something as Mississippians.’”

Indeed, upon returning from one of these week-long sessions, Anding and his cousin, A.M.E.’s son Willis Logan—serving as president of the Youth Council—decided in the summer of 1960 that some form of protest needed to occur in Jackson. They headed over to the Jackson Zoo and sat on a bench reserved for Whites only. The police were called, but nothing came of the infraction. The youth were just scolded and told to go home. The incident didn’t even make it into the newspapers. But Meredith had had his first taste of dissent against the established segregationist order—and his first scrape with the police, as well. Thus, he was not intimidated when the call came to participate the following March in the library sit-in.

Many of the Tougaloo Nine returned in August 2017 to Jackson for the unveiling of the Mississippi Freedom Trail marker commemorating their historic “read-in.” Pictured L-R: Beverly Hogan, then-President of Tougaloo College; Meredith Anding; Alfred Cook; Geralding Edwards Hollis; Ethel Sawyer Adolphe; Janice Jackson; Albert Lassiter; and James Bradford. (Gentleman at far right, unidentified.) [Anding family photo]

Like his other eight colleagues, Anding endured more than 30 hours in jail after his arrest for the library protest, including an arduous interrogation by detectives intent on pinning the lawless “read-in” on Medgar Evers. Despite repeated and harsh questioning, neither Anding nor his accomplices ever gave up any information that might incriminate their leader. Anding’s steely reserve and inbred confidence was something of a shock to the White detectives. “Your mother would be ashamed of you!” the cops admonished him. “No, she wouldn’t,” Anding calmly volleyed. “Why not?” they persisted. “Because my father pays taxes and I have a right to go to the library.”

Because of his participation in Mississippi’s first student-led civil rights demonstration, Anding lost his funding for college, which was being provided by a local church group, and was forced to suspend his education. Undeterred, he moved to Chicago for a year, then volunteered to serve in the Air Force security force. After four years, mostly spent in Turkey, Anding returned to Tougaloo and completed his Bachelor of Science degree with a specialty in Mathematics. He also gained acceptance into graduate school at the State University of New York at Buffalo for an advanced degree in Math. He met his wife Maurice while in grad school and the two forged a lifelong partnership. They stayed in Buffalo and made careers teaching mathematics and designing teaching protocols to help youth learn higher mathematics principles.

For their efforts, each of the Tougaloo Nine were awarded keys to the City of Jackson on October 14, 2006, 45 years after their historic nonviolent protest. [Key in Meredith Anding Collection]

Meredith Anding died on Friday, January 8, of complications from leukemia. Maurice survives him, as does the Andings’ son Armaan and several grandchildren. Their son Gordon, who had cerebral palsey, died in 2018.

In summing up his breakthrough activism, the example of which would lead many more of Mississippi’s young Blacks to challenge the segregationist system, Anding was, as usual, understated but eloquent. “We were the first to show resistance,” Anding said about the legacy of the Tougaloo Nine. “We were the pace setters. We seized a moment of time that had arrived for the state of Mississippi to move forward.”

Author M.J. O’Brien and Meredith Anding outside of the Anding’s home along the Niagara River in Grand Island, New York. Just like Anding, the seemingly quiet river disguises a powerful undercurrent below the surface. About 10 miles downriver, the placid Niagara River becomes Niagara Falls.

M. J. O’Brien is the author of the award-winning “We Shall Not Be Moved: The Jackson Woolworth’s Sit-In and the Movement It Inspired.” He is currently at work on a book-length narrative study of the Tougaloo Nine and their legacy.

#Meredith Anding#Tougaloo Nine#Tougaloo College#Meredith C Anding Jr#A.M.E. Logan#Medgar Evers#Breach of Peace#West Jackson Youth Council#NAACP#Mississippi NAACP#Beverly Hogan#Bennie G. Thompson Academic and Civil Rights Research Center#Jim Hill High School#Tougaloo Alumni

0 notes

Text

Books, Books, Books

Lists are all the rage at the end of any year and this plague year is no exception. Since I’ve read a fair number of books by friends this past year or so, I thought I’d send out my “Goodreads” reviews of all three books that I’ve enjoyed with the hope of giving each a bit more recognition (and perhaps a bump in sales) in the New Year. The reviews are presented in the order that I reviewed them. All three books are available on Amazon or through your local independent bookstore. Also try IndieBound, the online independent bookseller.

[End of Year Note: My apologies for not being more active on social media lately. I’m working on my own follow up to “We Shall Not Be Moved” and have tried to stay away from all forms of distraction, including social media. With any luck, my next project, the story of the Tougaloo Nine Library Sit-In, will be on its way to the publisher at the end of 2021.]

And now, for our 2020 BOOKS, BOOKS, BOOKS!

Wave On: A Surfing Story by Michael E.C. Gery

(Amazon Digital Services, 2018, 432 pages, Autobiographical Fiction)

[Reviewed August 2019]

"A wonderfully adept stoner’s diary for the boomer generation."

I was thoroughly enchanted with “Wave On” from beginning to end. Even when I wasn’t sure exactly where we were going, the ride was exhilarating. Perhaps it was because I knew many of the places where the action takes place: Williamsburg, the Outer Banks, Annapolis, Ocean City, College Park, and even The Who concert back in 1971 [or was it ’70?] at Merriweather Post Pavilion, which I also happened to attend!! I read very little fiction but a fair amount of biography and memoir, and I must say that I rarely find a work of fiction that is as engaging and heart-driven as “Wave On.”

Part One is a pure, lovely, romantic love story that is contemporaneous with our early adulthood and, thus, easy for me to put myself in the shoes of Cro as he tries to navigate the strictures of young adulthood in a laissez-faire new world of the mid-1960s. The fact that he has been schooled at an Episcopalian Boys school and loves all of those old hymns and prayers makes it all the more real for me, having attended a 4-year Catholic high school seminary. Cro’s goofiness, uncertainty, and (initial) shyness around women also resonated.

What I loved about Part One is that Gery establishes a voice for Cro, the Narrator, that is immediate, engaging, alive, and consistent throughout the entire novelization of what I believe is Gery’s young adult life. (A new term I just picked up--“autofiction” i.e., autobiographical fiction--seems to apply here.) Cro is so normal in his struggles to understand how the world works, so honest in his mistakes, so in love with his environment—the ocean, the waves, the shore—that he makes us love them, too, perhaps a bit more than we already do. But it is that voice that intrigued me throughout. No matter what kind of scrape Cro and his interesting band of friends and lovers gets into, there is a confidence that they are up to the challenge. [I must admit that Cro’s drift during Part Two with regard to his professional aspirations and even his family life was a bit baffling, but I came to think that the weed had a lot to do with his lack of ambition and direction.]

Part Two, of course, gets a bit more complicated as real life intervenes and our little Love Couple begins to encounter troubles from within and without. I hated to see that and was certain that Cro was going to lose his wonderful Ella and Adam and couldn’t see my way through to how it all might resolve, particularly when Maryanne enters the picture and the Neil Young Concert kiss betrays a problematic (if not fatal) flaw in our hero. But I suffered through all of that, wanting to see how it all came out in the end. Although there was no deus ex machina, the surprising turn of events that helps resolve these dramatic arcs is shocking yet consistent. It all made narrative sense and helped explain why we were taken on so many to such a happy ending.

“Wave On” is a wonderfully adept stoner’s diary for our boomer generation. I can’t wait for Gery’s next work of autofiction to continue the journey with him.

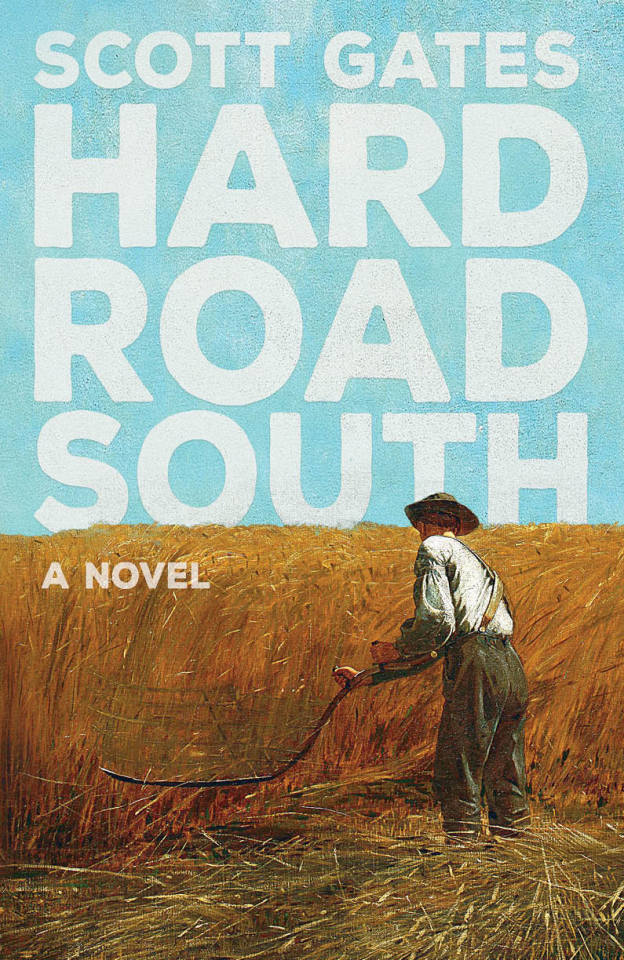

Hard Road South by Scott Gates

(Blue Ink Press, 2020, 254 pages, Fiction)

[Reviewed, May 2020]

“A little jewel box of a novel.”

“Hard Road South” is a little jewel box of a novel set during the early days of Reconstruction Virginia. This beautifully rendered tale imagines a naïve Connecticut Yankee—a former Union soldier—who travels South to visit and potentially settle in some of the lush foothills of the Shenandoah Valley where he once engaged the Confederate “enemy”. Hoping to find peace while helping to reform a culture that wishes to be left alone, our hero, one Solomon Dykes, finds fast friends but also fast enemies amidst the verdant pastures of his would-be Old Virginny Home.

An early scene sets the tone: A down on her luck woman is stopped in the town of Middleburg—the place that would become the enclave of the likes of millionaires John and Jackie Kennedy and Jack Kemp Cooke a century later—by some Union soldiers still on the scene occupying this “foreign” land to ensure compliance with Union directives. Her transgression? Wearing the Confederate uniform jacket of her dead husband. The three Confederate buttons on the jacket must be removed or she will be arrested and charged with treason. Such is the over-reach of conquering heroes.

Our damsel in distress is aided by the swift thinking of one Jeb Mosby, a local farmer, who pulls out his knife and gently removes the buttons so as to spare his life-long neighbor the embarrassment of arrest.

“Such was life now,” Mosby observes. “Filled with reminders—small as they may seem—that life would not soon be returning to how he’d left it before the war.”

It is small observations such as this that gives this book its charm and its weight. Representations of what life must have been like for the conquered South are constant reminders that the likes of Solomon Dykes were not at all welcome and most likely would be rebuffed should the opportunity arise.

Scott Gates is new to novel writing, but you wouldn’t know it from his sharp eye for detail and his pacing. Gates gives his story and his characters plenty of room to breathe and develop while providing the reader with glimpses of the specifics of their war-torn lives. A Southerner by birth, Gates offers a sensibility of one trying to bridge the great divide while not shying away from the difficulties building that bridge might require.

This is a tale for our time, as well, as our nation is once again fraught with deep divisions perhaps not seen since the ending of that great Civil War more than 150 years ago. We are stuck and unable to move forward until some fundamental rift gets settled.

“Hard Road South” is a highly readable, thoroughly enjoyable yet cautionary tale for our time. Perhaps we can learn from the past and this time get things right. Perhaps …

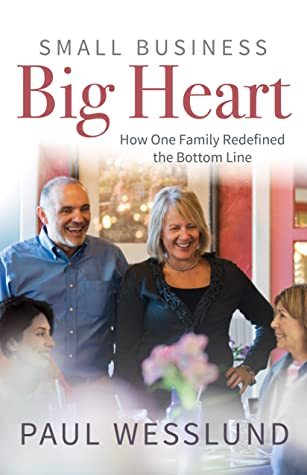

Small Business Big Heart: How One Family Redefined the Bottom Line by Paul Wesslund

(Highway 61 Communications, 2020, 242 pages, Nonfiction)

[Reviewed, August 2020]

“Big-hearted Book Teaches That Care for Others = Good Business”

In the midst of a global health crisis—the worst we’ve seen in generations—and while we struggle as a country, as a people, to find our footing morally and culturally during a reductio ad absurdum political creep show, Small Business BIG HEART lands as a corrective, a balm to soothe frayed nerves and intemperate minds. That is not to say that this big-hearted book is pablum. No, the stories it brings are all too real—people who often have lost their way through drugs, alcohol, and bad choices; refugees who have fled horrific circumstances and are looking only to start a new life but can’t due to the stigma of being different; and one family in particular that is faced with its own dissolution as well as the loss of its dream of a thriving family business. The high-stakes rollercoaster ride that journalist Paul Wesslund takes us on is dizzying not only for its incredible highs and sometimes tragic lows, but also because it introduces a concept too often forgotten … no, disregarded … in modern business life—what corporate governance experts would call “the duty of CARE.”

Sal and Cindy Rubino are two hard-working business owners who, through the course of their trials and tribulations, manage to hold on to the dream of a creating their own business from scratch while also enduring the inevitable personal strains that such a dream exacts. The two met and fell in love while working toward Hospitality Management business degrees in Miami, but the real story starts when they try and apply the lessons of their training in the difficult day-to-day drudgery of actually running their own restaurant—simply named “The Café”—in an offbeat, run-down section of Louisville, Cindy’s hometown. It is here that their skills and wills are tested to the limits and each will have to adjust their visions to fit the realities not explored in textbooks. And it is here that their hearts will be broken, and then opened to the truths that adaptability and innovation can be applied not only to recipes and business models, but to the very people you employ and the methods you use to build a team for success.

Along the way, we meet all manner of broken individuals. The restaurant business is notorious for laying waste to lives due to its thankless dawn-to-dusk hours and the constant requirement to please the customer at all costs. Wesslund has an expert’s eye for the telling detail and the wrenching story line. [I found myself tearing up at any number of stories throughout this engaging, nonfiction tale.] His twenty years as editor-in-chief of Kentucky Living, the largest circulation monthly magazine within the state, shows in the well-drawn portraits of individuals from as far away as Bhutan and as near as Pricilla’s Place, a half-way house just a few blocks from the Café, where Cindy and Sal would find some of their best employees. Perhaps Wesslund’s (not to mention the Rubinos’) refusal to judge people by the standards of upwardly mobile middle-class values but instead, with extraordinary discernment, to look deeper into their souls to spot their special sparks and unique talents is the hallmark of this extraordinary book.

It is rare outside of evangelical circles to find a book that so openly espouses Christian principles, but Sal and Cindy make no bones about the fact that their faith community helped to save their marriage as well as their business, and Wesslund recounts the strength of those relationships and the power of religious inspiration with rare delicacy. Yet the book is not all seriousness and drama. We get, of all things, recipes (!) at the start of nearly every chapter—a creative way of introducing a new topic or the next development of this constantly churning story. And we are introduced to Cindy’s creative cooking style, to Sal’s winning smile and to their gracious, open approach to hospitality.

Small Business BIG HEART runs the gamut of the small business life cycle. It is a soup-to-nuts (literally) primer on the ups and downs of small business management. As such, it is tough medicine for anyone daring to think of creating their own start-up. Given that, however, it provides a deeply affecting microcosm of how we as a society—as a culture—might live if we, indeed, saw everyone we encountered as a member of our own family. It does not skimp on the tough decisions that must be made to keep a business afloat—the “tension between compassion and the bottom line”—but it provides a template on how to “run a business with heart”—where everyone can be a winner.

Wishing you a New Year full of new books, new ideas, new opportunities, new promise.

#Michael Gery#Wave On: A Surfing Story#Scott Gates#Hard Road South#Paul Wesslund#Small Business Big Heart#Top Books of 2020

0 notes

Text

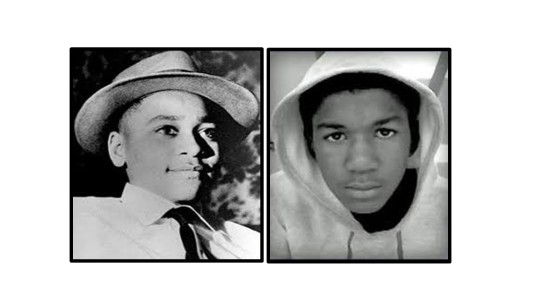

The Trayvon Martin Generation Comes of Age

WHAT IS NOW KNOWN in certain circles as “the heroic civil rights movement” got its jump start, many would say, with the horrific torture and murder of a 14-year old boy named Emmett Till in 1955. Till’s assassination made headlines around the world and slowly, oh so slowly, things began to change. There was 42-year-old Rosa Parks’ dramatic decision not to move from the seat in the Whites-only section of the bus just three-and-a-half months after the slaying, citing Till as her point of reference for her refusal. There were the nine Black students determined to enter the all-White Little Rock High School in 1957, thanks largely to their adult coordinator and leader, the 42-year-old Daisy Bates. This was another headline-grabbing moment that alerted Americans of all stripes that all was not well in the Southland and that Freedom was a-stirring within the hearts of its Black populace.

But it wasn’t until North Carolina’s 1960 Greensboro sit-in and the wave of protests that followed in literally hundreds of cities throughout the U.S. in the ensuing months and years—coordinated and executed primarily by young college and high school students throughout the South—that things really took off. It was then that America began to listen to the voices of nonviolent protest and started to understand the depth of the racial divide that separated the country. The timing of these seemingly spontaneous acts of civil disobedience should have surprised exactly no one. They were, in large part, the direct result of the Emmett Till murder and the failure of the American jurisprudence system to prosecute that heinous crime and bring Till’s murderers to justice.

Perhaps it was Anne Moody in her powerful memoir Coming of Age in Mississippi, who first gave voice to the obvious radicalization that took place of many Black children in the mid-1950s. In vivid prose, Moody details how she first heard of Till’s murder while on her way home from high school, and what a shock it was that someone her very age could be killed for something so seemingly innocent as flirting with a White woman. After days of hearing more about the murder from both her own family and from the White family she did housekeeping work for, she recalled feeling something that would animate her future activism:

Before Emmett Till’s murder, I had known the fear of hunger, hell, and the Devil. But now there was a new fear known to me—the fear of being killed just because I was black. This was the worst of my fears. I knew once I got food, the fear of starving to death would leave me. I also was told that if I were a good girl, I wouldn’t have to fear the Devil or hell. But I didn’t know what one had to do or not do as a Negro not to be killed. Probably just being a Negro period was enough, I thought.

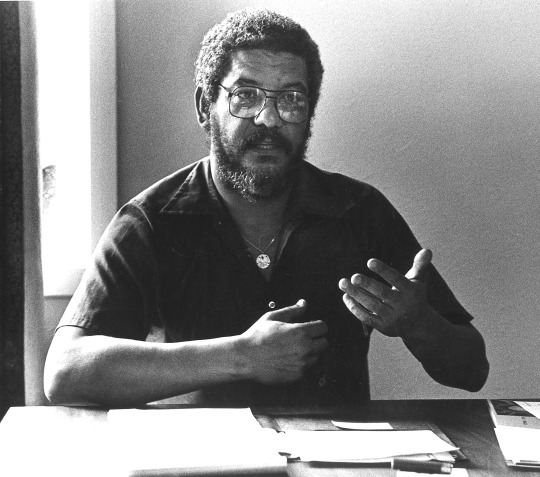

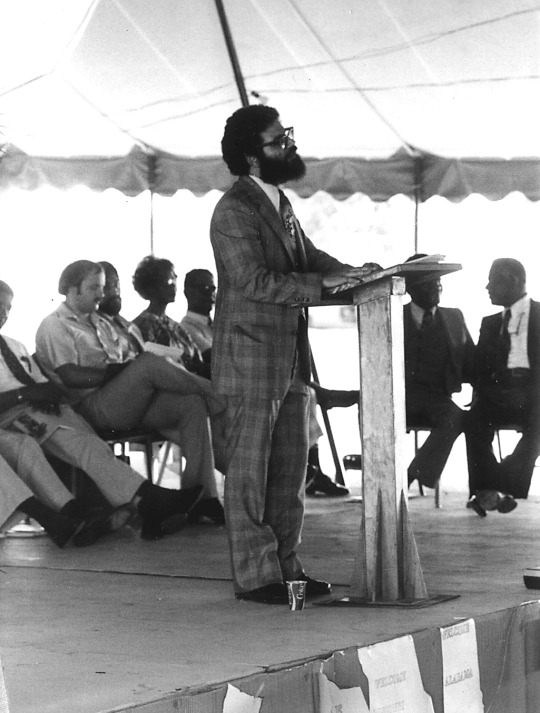

Anne Moody (right) with friend Joan Trumpauer and Tougaloo professor and mentor John Salter at the Woolworth’s counter in Jackson, Mississippi in 1963.

That simple realization, based on her knowledge that she was in the same boat as Till—and the very same age as he had been—would, less than eight years later, drive Moody into the vanguard of the civil rights movement on the streets and at the lunch counters of Jackson, Mississippi. In time, she would become a powerful spokesperson for the cause not only through her breakthrough memoir but also through her rousing public speaking to raise funds for various civil rights organizations.

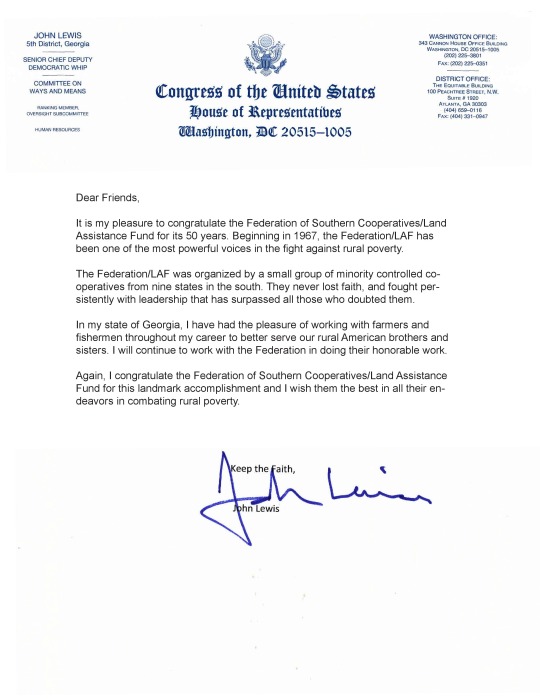

MOODY’S STORY IS NOT SINGULAR. Many civil rights veterans today point to the wanton and senseless murder of young Till as their touchstone for later activism. In his award-winning “Memoir of the Movement” Walking with the Wind, longtime Georgia Congressman John Lewis recounts with similar shock and awareness what the Till killing meant for him and his generation of young Black men:

As for me, I was shaken to the core by the killing of Emmett Till. I was fifteen, black, at the edge of my own manhood just like him. He could have been me. That could have been me, beaten, tortured, dead at the bottom of a river. It had been only a year since I was so elated at the Brown decision. Now I felt like a fool. It didn’t seem like the Supreme Court mattered. It didn’t seem that the American principles of justice and equality I read about in my beat-up civics book at school mattered. . . . They didn’t matter to the men who killed Emmett Till.

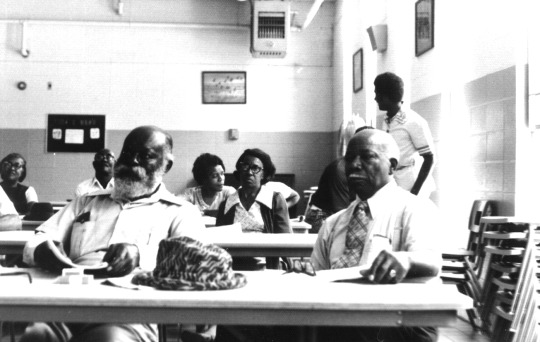

SNCC Chairman John Lewis speaking at the March on Washington in 1963.

Less than five years later, Lewis would become an essential member of the Nashville sit-in movement, an incorporating member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee—later elected its Chairman—would give an incendiary speech at the March on Washington and, in 1965, would demonstrate an enduring example of commitment to the Struggle when he was beaten bloody on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma.

Historians estimate that 70,000, mostly youthful citizens participated in the sit-in movement across hundreds of cities throughout the U.S. Not only could they point to injustices done to themselves or their families, but they could point to the example of Emmett Till, which caused them to understand, as Bob Dylan so adeptly pointed out, “When you ain’t got nothin’, you got nothin’ to lose.” They were called “The Emmett Till Generation.” They put their bodies on the front lines and brought about essential change to 1960s America. It was THESE Americans who caused the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1964—introduced by President Kennedy just months before his death—and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

NOW, ONCE AGAIN, AMERICA IS IN AN UPROAR. Black men continue to be killed at disproportionate rates by police and by White vigilantes nationwide. Once again, the rage has reached a critical tipping point. And the timing is directly linked to the killing of a Black youth, Trayvon Martin, eight years ago. So many young black men point to the shocking murder of Martin as the point at which they came to consciousness about America’s two-tiered system of justice. On Monday, June 1, young activist Jaden Olley, at a rally for George Floyd on the streets of Washington, DC, spoke to the PBS Newshour: “I was eight-years old when the Trayvon Martin case happened,” he said. “Ever since then, I understood that it could be me.”

My own sons, now twenty-seven and twenty-five—both young Black men—came to the same conclusion at the same time. It was in late February 2012, upon hearing of the Martin killing, that my wife and I had to have “the Talk” with these youth on the verge of manhood. One was born just three months after Trayvon Martin had been; Martin had just turned 17 when he was murdered. We had to urge them to be careful even in our own peaceful and progressive neighborhood in Northern Virginia. [Martin, as you may recall, was walking through a gated community on his way to his father’s home in the Orlando suburb of Sanford, Florida.] Our older, more sociable son admitted that ever since he was twelve, he had realized he needed to put on a smile and reassure our overwhelmingly White neighbors that he was friendly, safe, and non-threatening while walking through his own neighborhood. Imagine what a terrible burden that reality must be to carry day-to-day.

You can be assured that other young people, both Black and White, were traumatized by the Trayvon Martin killing. Not only did they see someone their own age murdered, but they later saw the murderer get off without any serious consequences for his tracking and terrorizing a Black youth. It was a shocking moment for them – just as the exoneration of the Emmett Till killers had been for an earlier generation. And then they watched as the murders continued: of Michael Brown (18), of Eric Garner (43), of Philando Castile (32), of Sandra Bland (28), of young Tamir Rice (12), of Laquan McDonald (17), of Freddie Gray (25), of Natasha McKenna (37), of Walter Scott (50). And not a damned thing happened. Many of those watchful youth determined at some point along that trajectory that if they ever had a chance to do anything about such matters, they would take charge and insist that the police keep ALL Americans safe.

That moment has now come.

AFTER WATCHING THE HORRIFFIC VIDEO of George Floyd’s murder at the hands of the Minneapolis police, thousands of young people have turned out in cities across America to express their outrage that these unconscionable criminal acts--by those who pledged to protect and defend us--have not yet been eliminated. This is the Trayvon Martin Generation coming of age and rising up to express their rage and to say that “this will not continue on my watch.”

One hugely encouraging development since the early 1960s is the overwhelming number of Whites—young, old, and in-between—who are standing with their Black brothers and sisters in the streets. This is vastly different from the few Whites who committed to the struggle in the early 1960s. Joan Trumpauer, who sat with Anne Moody at thet Woolworth’s counter in Jackson, and her ilk were the exception—at least until the 1964 Freedom Summer brought hundreds of White college students to Mississippi. That experience would change the trajectory of their lives.

Think of how many lives are being transformed today on the streets of America’s cities—standing up for racial justice in the face of overwhelming odds. Indeed, thousands of Whites are publicly expressing outrage that such brutality against Blacks continues. Some are even putting themselves between their Black friends and activists and the police, using their White privilege to good effect.

But the pushback has been equally ratcheted up due to an erratic, power grabbing, unstable national leader and the craven politicians and bureaucrats who do his bidding. No matter. All of the ridiculous posturing and unlawful acts by this illegitimate President—John Lewis was the first person to publicly use this moniker—will not quell the fire that has been lit by the Trayvon Martin Generation’s coming of age. Nothing short of federal legislation reining in police forces nationwide and requiring equal protection to all of America’s citizens will quench this rage. Just like their heroic forebears in the Struggle, this generation has its Eyes on the Prize. And They Shall Overcome.

#Trayvon Martin#Emmett Till#Anne Moody#John Lewis#George Floyd#Michael Brown#Eric Garner#Philando Castile#Sandra Bland#Tamir Rice#Laquan McDonald#Freddie Gray#Natasha McKenna#Walter Scott#The Trayvon Martin Generation#The Emmett Till Generation#Joan Trumpauer#John Salter

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Soupkitchen

It was my friend from college days, Robert Hoderny, who invited me down to the Zacchaeus Soup Kitchen when we both ended up in the mid-to-late 1970s in the Washington, DC area. Robert, already a Vietnam Veteran, joined the seminary at about the time I was planning to exit, but we kept in touch. He quickly grew disenchanted with the Church bureaucracy and left for more progressive pastures and ended up in DC with the Community for Creative Non-Violence (CCNV). When I returned from my sojourn to the Midwest, mostly a 2-year stint in Midland, Michigan (recently in the news due to a horrendous dam collapse and horrible flooding in the downtown area), I found Robert staying at some Augustinian guest house near Catholic University, participating in CCNV planning meetings, teaching religion and a new course in nonviolence, poverty and ethics at Carroll High School, and serving up soup at the soup kitchen. He invited me down one weekend and I became a somewhat irregular volunteer for the next five years.

When I was asked to write a short feature article in my American University journalism class, again taught by my beloved Professor Tinkelman (honestly, he was NOT the only professor on staff there!), my mind turned to my experiences at the soup kitchen and figured it might make an interesting piece. I was right. Not only did Tinkelman love it—he read it aloud to the entire class to my utter public embarrassment and private delight—but he also suggested I try and publish it. Ten months later, this, my first published piece, would appear on the cover of The Washington Tribune, DC’s-then most popular local weekly newspaper. (Today, The City Paper, is its successor.)

As a bonus feature to my five-part series on Dorothy Day, here is that piece, as originally written, in its entirety….

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Michael J. O’Brien Soupkitchen 7/21/82

He sits as if transfixed, half dazed, staring down at the bowl of steaming soup on the table in front of him. He is black, unshaven, with the smell of cheap wine on his breath. His clothes don’t fit. They are dirty and torn. He carries his belongings in the plastic trash bag that is always at his side. He looks tired, no, exhausted, by the constant worry that life on the streets can bring. He is not alone.

He is one of the hundreds that daily filter through the Zacchaeus Community Kitchen. Some are young. Some are old. Most are black. All are poor. Many, like this man, claim the streets for their home. They come to the kitchen for some daily nourishment: a bowl of soup, a slice of bread, and some shelter from the storm of street life.

Zacchaeus Kitchen, located inconspicuously in the 600 block of L Street, NW, has been the breakfast table for thousands of Washington, DC’s poor for almost 10 years. Started by a group of caring activists who call themselves the Community for Creative Non-Violence (CCNV), the kitchen remains one of the few places in the city where a person can, with no hassle, with no questions asked, get a decent meal for free.

Mother Theresa, the saint of Calcutta, served the kitchen’s first bowl of soup in October of 1972. CCNV founder Ed Guinan remembers the occasion this way:

“Zacchaeus Kitchen was our first real poverty program. When we decided to go with it, we rented a small place on New York Avenue. Mother Theresa happened to be in Washington at the time, so we invited her over to help launch the thing. I made the soup and she ladled it out to the twelve or fifteen people who came by that day.”

Guinan expected to serve only 40 to 50 walk-ins per day. But in a few months, after word got out, more than 150 of the city’s poor and homeless were coming to the kitchen for their daily meal. The New York Avenue space proved inadequate for the crowd, so the Community found another space—its present L Street location—to set up kitchen headquarters. Now, Guinan says, more than 300 come to the kitchen every single day.

The Community takes responsibility for seeing that there is enough food as well as enough people to cook and serve each day. They accept no government subsidy.

Much of the food is donated. Over the past 10 years, CCNV has established a network of generous Church groups and wholesale food outlets that supply canned goods and surplus produce. Ottenberg’s bakery has given its surplus bread to the kitchen since the program began.

Volunteer workers come from all over: church groups, Catholic high school students, committed teachers, government workers, and other who somehow heard about the kitchen’s work and decided to get involved. CCNV members fill in during the work week when volunteers are scarce.

The kitchen also gets help from the District’s court system. Offenders with minor violations are sentenced from 10 to 300 hours of service at the kitchen, depending on the nature of their misdemeanor. “We couldn’t do it without them,” one volunteer said. “Sometimes they’re the ones who keep this place going.”

A typical day at the kitchen beings when workers start to trickle in at about 6:30 a.m. Usually, someone has already put the water on to boil the night before, so the first step is to add the beans to the steaming cauldrons, since beans take a long time to cook. Workers then slice onions, potatoes, carrots, celery, tomatoes, and whatever else can be found to make the soup interesting and palatable.

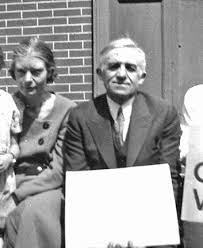

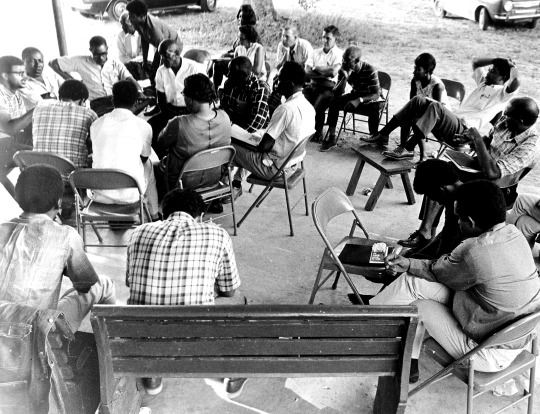

Former priest and then-poverty pioneer Ed Guinan (with wife Kathleen) at the first iteration of Zacchaeus Community Kitchen in Washington, DC, in the 1970s.

Rarely is there any meat for the soup, but when there is, it usually must be picked from the bones of hams, turkeys, or chickens that have already been served to more privileged groups at restaurants and posh dinner parties throughout the city. This is the leftover kitchen: the place that serves food that nobody really wants to people whom almost everyone would prefer to forget.

Anarchy reigns once the workers get geared up. One person is designated chief cook, but others give their advice—asked for or not.

“The soup looks kind of thin to me. What do you think?

“Maybe we can put in some noodles to thicken it up.”

“How about some of this seasoning stuff?”

“It needs more onions, lots of onions!”

Similar deliberations continue until about 9:15 a.m. when, ready or not, the doors open to the hungry masses awaiting their first, perhaps their only, meal of the day.

The ragged crowd shuffles through the downstairs cooking area, up the steps to the serving room. The room can comfortably accommodate 50 to 60 people. It is always crowded. On nice days the tables and benches are set outside on the sidewalk, adding a café flair to an otherwise dank and dismal atmosphere.

The serving room is usually serene enough before the onslaught. Trays of bread sit neatly on each table along with pitchers of hot tea (in the winter) or Kool-Aid (in the summer). Once the crowd enters, however, the place turns into a bombshell of congestion and confusion.

The hungry are asked to take a seat while volunteers serve them. One worker hurriedly ladles out the soup into oversized bowls as others rush to bring each bowl, along with an empty cup and spoon, to the tables. The process of serving each person individually takes a long time and often the demands of the crowd can overwhelm the small band of workers.

“Can I have a bowl of soup over here?”

“Where’s my cup?”

“Got any sandwiches today?”

“Why can’t you get some heat in here?”

“Can I take a loaf of bread home with me?”

“How about a cigarette, man?”

This kind of chaos continues for about two hours. The noise is terrible. The smell is worse. Tempers run short. Fights break out often. Somehow everyone gets fed.

By 11:30 a.m., after three huge pots of soup and countless loaves of bread have been devoured, after hundreds of people have found their way in and out of the kitchen doors, the place begins to quiet down. Workers wash the dishes and mop the floors. When the last few stragglers have been ushered out, the windows are shut, one final inspection is made, then the doors are closed and locked. The poor have been given their daily bread for another day.

On the wall by the stove where the soup is prepared, a newspaper clipping is taped. It contains the words of a man who did similar work with the poor more than 100 years ago. His assessment of the job of feeding the hungry seems strikingly valid for those who help out at Zacchaeus Kitchen. He told his workers”

“You will find out that charity is a heavy burden to carry, heavier than the bowl of soup and the full basket . . . . You are the servants of the poor, always smiling and always good humored. They are your masters, terribly sensitive and exacting masters, you will soon see. The uglier and dirtier they will be, the more unjust and insulting, the more love you must give them. It is only for your love alone that the poor will forgive you the bread you give to them.”

--St. Vincent de Paul

#Zacchaeus Soup Kitchen#Ed Guinan#Vincent de Paul#Community for Creative Non-Violence#CCNV#robert hoderny#Joe Tinkelman#American University School of Communications#AUSOC#Kathleen Guinan#Soupkitchen

0 notes

Text

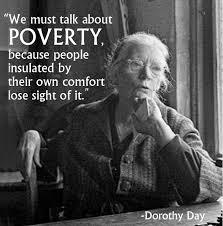

Dorothy Day - “Dissenting Voice of the American Century”

During this month of memorialization of the 50th anniversary of the Kent State atrocity—where students protesting American military aggression in Vietnam were gunned down on their own campus—it is well to remember that The Catholic Worker staged the first public protest against the Vietnam War way back in the summer of 1963 while this misguided attempt at containing Communism’s spread was in its early stages. Read all about this and more of The Catholic Worker’s incredible legacy of protest and resistance in Part V, the last of my series on Dorothy Day and her pioneering newspaper. [Links to the previous four posts in this series can be found at the end of this article.]

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

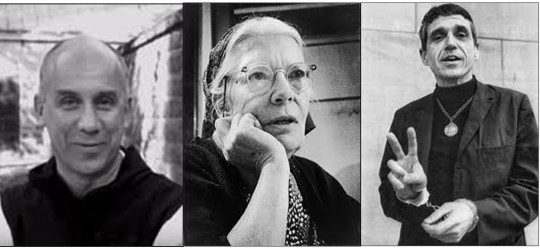

Vietnam

The Catholic Worker began featuring the radical pacifist writings of Cistercian monk Thomas Merton, as well as those of brothers and Catholic priests Daniel and Philip Berrigan as early as 1959. Others affiliated with The Worker organized the Catholic Peace Fellowship, an organization aimed at educating Catholics on the Church’s neglected tradition of pacifism. When news of the Vietnam War broke, The Catholic Worker was ready.

The first demonstration ever held to protest the war was held by The Catholic Worker in the summer of 1963. It was tiny, but after a ten-day period, The War Resisters League brought two hundred and fifty people to join the Workers. Together they made national television and launched the protest movement against the war.

When Congress passed a law in 1965 forbidding the burning of draft cards, The Catholic Worker called for public draft card burning. David Miller, a Worker volunteer, burned his card and caused an international sensation. Another Worker, Tom Cornell, had gained some notoriety as early as 1960 by burning his draft card at a demonstration against the launching of the Polaris submarine. Later, five other Workers, including Cornell, burned their cards at a rally in Union Square.

Dorothy Day heartily supported the protests and spoke at the rally:

… I speak today as one who is old, and must endorse the courage of the young who themselves are willing to give up their freedom. I speak as one who is old, and whose whole lifetime has seen the cruelty and hysteria of war in the last half century. . . .

I wish … to point out that we too are breaking the law, committing civil disobedience, in trying to encourage all those who are conscripted to inform their consciences, and to heed the still, small voice, and to refuse to participate in the immorality of war.

Counter demonstrators across the street shouted at her, “Moscow Mary! Moscow Mary!” Others yelled, “Give us Joy! Bomb Hanoi!” and “Burn yourselves, not your draft cards.”

Roger Laporte, a Catholic Worker volunteer present at the rally, heard the cries of the counter-demonstrators and, perhaps as a witness to others that he was willing to do anything to stop the war, took their demands seriously. A few days after the rally, at five in the morning, LaPorte bought a can of gasoline; walked to the Secretariat Building of the United Nations; sat down on the landing of the Isaiah Stairway under the words carved into the walls: “They shall beat their swords into ploughshares, neither shall they study war anymore”; poured the gasoline over himself and struck a flame. He died the next day. The incident made international news.

Isaiah Stairway at the United Nations Plaza in New York City.

The very night of Laporte’s self immolation, almost as if Heaven wished to mark the sacrifice of this youth and the thousands more that were to die in Vietnam, all the lights went out from New York City to Montreal. It was the night of the Great Blackout of 1965.

The Catholic Worker came under heavy criticism by the Catholic press for this action by one of its members. Although no one suspected LaPorte would consider such an extreme measure, Dorothy Day felt some responsibility for the tragedy. She never criticized LaPorte’s act, but she was badly shaken by it and called for strenuous prayer and fasting. She prayed that Roger LaPorte’s sacrifice would be accepted by God and that no one would follow his example.

The Catholic Worker continued its support of the Peace Movement. It called for massive resistance to the draft and for men to refuse payment of taxes that went to support the war effort. The Berrigans wrote lengthy articles for the paper detailing accounts of their acts of civil disobedience against the war.

When Cardinal Spellman went to Vietnam for his Christmas visit and called for victory in the war, Dorothy Day decried his statement in the article, “In Peace is My Bitterness Most Bitter.” She paraphrased Christ’s words, writing “Our worst enemies are those of our own household,” and said, “What words are those he (Spellman) spoke against even the Pope, calling for victory, total victory? Words are as strong and powerful as bombs, as napalm.”

Viva La Huelga!

The Catholic Worker also took up the cause of Cesar Chavez and exposed the plight of the migrant farm worker. Chavez was trying to organize the vast migrant worker population into a union and, thus, force growers into paying better wages and providing better treatment to the migrants. The Catholic Worker brought national attention to Chavez’s cause. The paper carried accounts of Chavez’s activities in the fields of Delano, California, and of the increasing harassment by the growers. The paper called for a boycott of non-union grapes and lettuce and for the picketing of any supermarkets that did not carry union-approved products. [Some of my fellow seminarians and I would make trips to local Baltimore supermarkets on Saturday mornings in the early 1970s to test their produce and urge grocers and their customers not to buy scab, non-union grapes and lettuce.]

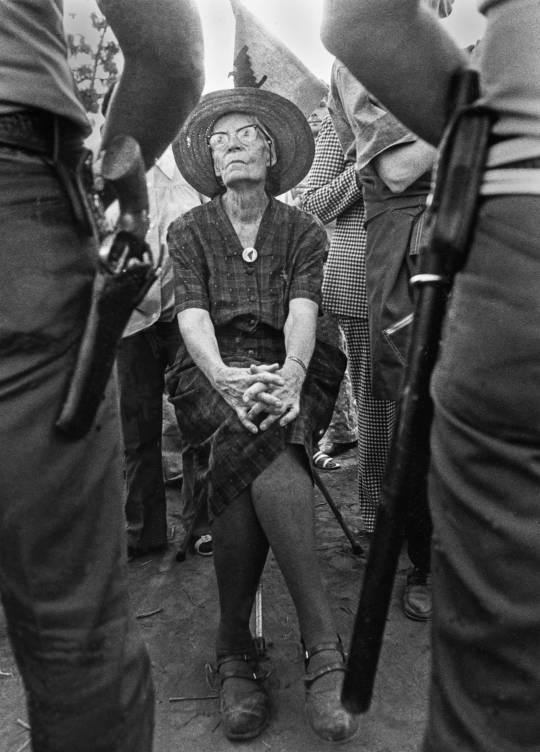

Dorothy Day’s final arrest was in collaboration with fellow Catholic Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers in 1973.

The Seventies

The Catholic Worker carried its opposition to the Vietnam War into the 1970s. It continued to call for war tax resistance and draft resistance. Letters or articles by the Berrigan brothers, written from their jail cells, were prominently featured.

In the summer of 1971, Dorothy Day made another pilgrimage, this time to Russia. As in Cuba, she recounted her experiences with the Russian people and reported on the country’s economic conditions, as well as on how the Church was surviving alongside its godless counterpart, the State.

In 1973, at the height of the United Farm Workers’ strike, Day went to Fresno to participate in a non-violent demonstration aimed at bringing attention to the illegal jailing of union members who picketed the growers’ fields. She went to jail with nearly one hundred other demonstrators. She was 76 years old.

The Catholic Worker accepted articles from friends around the globe who sought to bring attention to injustice in their own locales. Stories on Northern Ireland terrorism, on Philippine repression, on strip mining in West Virginia, on resistance in Brazil, on tragedies in Bangladesh, and on the Attica Prison uprising all appeared in the paper, along with instructions in nonviolent resistance and pieces on cooperative land-holding and voluntary poverty. The Worker’s outcries against the U.S. nuclear weapons arsenal continued, as many Workers went to jail because of their symbolic, attention-getting protests against the nuclear arms buildup.

Dorothy Day’s Death – The Work Continues

Dorothy Day died in November of 1980, at the age of 83. Her last years were spent in semi-retirement. She did not travel much after 1976, when her health began to fail, but she continued each month to write her journal “On Pilgrimage” for the paper. [I discovered through reading her columns that Day was, indeed, at Maryhouse three years ago when we visited. She was confined to her room, but her spirit permeated the halls of the place.]

While retired, Day continued to do what she could for the poor and dispossessed of this world. Three hours before her death, she was on the phone begging for aid for the victims of a devastating earthquake in Southern Italy.

The paper and the movement continue. Two Workers, Marj Humphrey and Peggy Sherer, edit the paper. Other Workers manage the two New York City Houses of Hospitality (Maryhouse and St. Joseph House); they feed hundreds each day, and give shelter and clothing to those who have none. The paper still relies on appeals in the Spring and Fall for the means to continue the work. Marj says that it costs more than $10,000 each month to print and distribution the paper, and that circulation figures are back up to a healthy 95,000 (mostly as a result of the Anti-War Movement of the sixties and seventies).

The paper still sells for a penny a copy (twenty-five cents for a year’s subscription) and is intent on carrying on the work that Peter and Dorothy began almost fifty years ago. Recently incidents in El Salvador, Guatemala, Chile, the Philippines, and Korea have been highlighted—each article written by someone with first-hand experience and knowledge of the horrors committed in these terror-torn countries. One need not be a Catholic to submit an article or to work for the paper—only subscribe to the basic tenants of the Catholic Worker philosophy.

Of course, there is always room in the paper for one of Peter’s “Easy Essays” or for one of Dorothy’s old articles, along with pieces about farming (The Worker still maintains a farm in Marlboro, New York), about activities at the Houses, and about the problems of being poor in New York City.

Concerning the future of the work, Marj Humphrey says, “It’s all in God’s hands. We will continue as long as He allows it.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

In the final lines of her 1952 autobiography The Long Loneliness, Dorothy Day remembered how it all started:

We were just sitting there talking when Peter Maurin came in.

We were just sitting there talking when lines of people began to form, saying “We need bread.” We could not say “Go, be thou filled.” If there were six small loaves and a few fishes, we had to divide them. There was always bread.

We were just sitting there talking and people moved in on us. Let those who can take it, take it. Some moved out and that made room for more. And somehow the walls expanded.

We were just sitting there talking and someone said, “Let’s all go live on a farm.”

It was as casual as all that, I often think. It just came about. It just happened. . . .

The most significant thing about The Catholic Worker is poverty, some say.

The most significant thing is community, others say. We are not alone any more.

But the final word is love. At times it has been, in the words of Father Zossima, a harsh and dreadful thing, and our very faith in love has been tried through fire. . .

It all happened while we sat there talking, and it is still going on.

“It is still going on,” and it is a comforting thought that the work will continue as long as God allows it. With any luck, He’ll allow it to go on forever, or at least until the need no longer exists.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

This ends my series on Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker Movement and newspaper. Here are the links to the other posts from this series:

Part I: https://blog.notbemoved.com/post/615785179039039488/dorothy-day-and-her-hope-filled-revolution-of-the

Part II: https://blog.notbemoved.com/post/616481057106264064/the-catholic-worker-always-found-room-for-one

Part III: https://blog.notbemoved.com/post/616931763626868736/dorothy-day-and-her-catholic-workers-didnt-skimp

Part IV: https://blog.notbemoved.com/post/617658737377820672/civil-disobedience-and-the

For more information about Dorothy Day and her legacy, check out the new biography by John Loughrery and Blythe Randolph [Dorothy Day: Dissenting Voice of the American Century] and the new documentary by Martin Doblmeier [Revolution of the Heart: The Dorothy Day Story]

#Dorothy Day#Peter Maurin#Daniel Berrigan#Philip Berrigan#Berrigan Brothers#Thomas Merton#Vietnam#Vietnam War#Caesar Chavez#Farmworkers Union#Roger Laporte#David Miller#Tom Cornell#draft card burning#Viva la Huelga!#The Long Loneliness#Marj Humphrey#Peggy Sheerer

0 notes

Text

Civil Disobedience and the Legacy of The Catholic Worker

After publishing last Part III of this series last week, a friend and colleague commented how unfortunate it is that the conservative Supreme Court justices (all of whom profess to be Catholic or were raised Catholic) do not seem to share this passion for social justice that Dorothy Day embodied. I agree and find it confounding. The Catholic Church took a hard-right turn in the 1980s and continues on that path today, despite Pope Francis’s best efforts. In any event, it is well to remember that there is (or was) a place in the Church for dissenters, for activists, and for those with a passion for the poor and afflicted—even if they don’t make it to the highest echelons of ecclesiastical or political life.

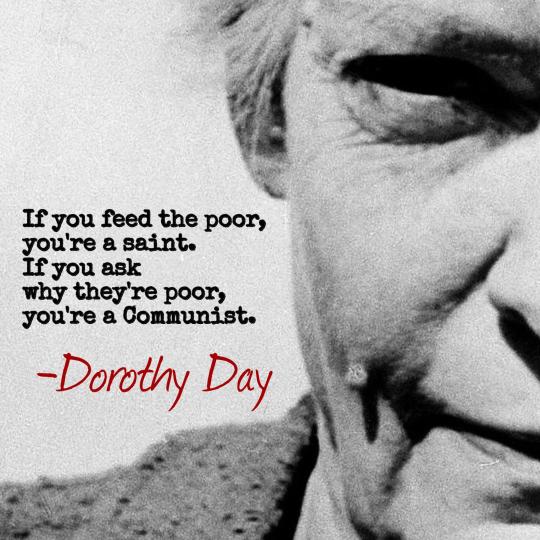

Dorothy Day never seemed much interested in climbing any ladders or achieving a certain status within the Church she served. “Don’t call me a saint,” she would say. “I don’t want to be dismissed that easily.”

Here’s Part IV of my series on Dorothy Day and the history of The Catholic Worker newspaper.

*********************************************************************************

The Post-War Period

After Peter’s death, Dorothy Day continued to publish the paper, to run the New York House of Hospitality, and to oversee the growing Catholic Worker Movement. By the start of 1950, the paper’s circulation had increased slightly to 60,000; circulation remained at this plateau throughout the fifties.

The paper was still an eight-page tabloid and it looked the same as it had for more than 15 years. Only woodcuts were used for artwork; photographs were too expensive to print. In the thirties and forties, the paper featured woodcuts of Catholic worker-saints—St. Peter the fisherman; St. Paul writing in prison; St. Joseph the Worker, and many others—all the handiwork of Worker Ade Bethune.

Woodcuts by Ade Bethune ...

In the fifties, another artist, Fritz Eichenberg, produced some stunning works of art for the paper. Eichenberg, a Quaker, portrayed most sensitively in his woodcuts and engravings the spirit of The Catholic Worker. His “Christ on the Breadline,” “The Labor Cross,” and “Last Supper,” captured visually what The Worker’s writers were trying to express in words. Day wanted to touch those poorest of the poor who could not read so she often printed full, front-page reproductions of Eichenberg’s work.

... and Fritz Eichenberg graced the pages of nearly every issue of The Catholic Worker.

The Catholic Worker continued to be built around Dorothy Day’s writing. She changed the name of her column to “On Pilgrimage,” a title that seemed to describe the nature of her life.

Others contributed articles regularly. Michael Harrington, a resident Worker who later became an economist, consistently provided pieces for the paper. Harrington’s most famous work, The Other America, written in 1961, is said to have sparked the Kennedy/Johnson War on Poverty. Ammon Hennacy, a pacifist anarchist, wrote extensively of his “one-man revolution.” Robert Ludlow, an intellectual and lover of Gandhi’s principles of nonviolence—he wrote a striking piece on Gandhi’s death—became an associate editor of the paper. Columns about the day-to-day activities of the House of Hospitality and about life on the farm provided engaging copy each month.

More Issues

The Catholic Worker continued to fight for justice and peace. When the underpaid gravediggers of Calvary Cemetery—Catholics and members of a CIO union—went on strike against New York’s Cardinal Spellman, Dorothy Day supported the gravediggers. The Cardinal thought the strike was inspired by Communists and refused to negotiate. He even used seminarians, of all people, to break the strike and forced the striker to dissolve the CIO affiliation and join an American Federation of Labor union instead. Day criticized the Cardinal’s tactics and the “shameful seminarians” who broke the strike.

At the onset of the Nuclear Age, The Catholic Worker denounced the continued testing of the A-bomb and the development of the H-bomb, and called for total disarmament of nuclear weapons. Indeed, The Worker even criticized the Catholic press for its “unbalanced” portrayal of Russia and its people.

The paper also opposed the anti-Communist Smith and McCarran Acts:

Although we disagree with our Marxist brothers on the question of the means to use and to achieve social justice, rejecting atheism and materialism in Marist thought and in bourgeois thought, we respect their freedom as a minority group in this country…. We protest the imprisonment of our Communist brothers and extend to them our sympathy and admiration for having followed their conscience even in persecution.

The paper continued to criticize the Capitalist system. “Communism, considered as an economic system apart from its philosophy, is not so much the antithesis, the opposite and the contradiction of Christianity as Capitalism is.” Such critiques did not win the paper many friends in the highly charged “Red-Scare” atmosphere of Joe McCarthy America. One priest wrote to ask The Catholic Worker, “Why don’t you come out in the open, declare yourselves Bolshevik Communists and fight the Church like men?” Day, a woman, stood firm, even quoting the Popes and their attacks on economic materialism and Capitalism.

Civil Disobedience

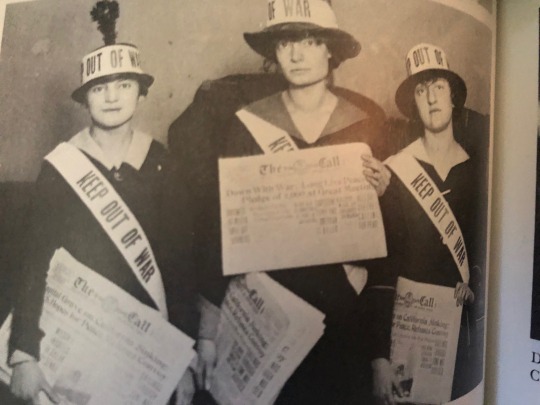

In 1955, seven Catholic Workers, including Dorothy Day and Ammon Hennacy, staged a protest with twenty-three others from the War Resisters League against New York City’s annual air-raid drill. The Civil Defense Act required that all take shelter for at least 10 minutes.

The Workers considered the drills scare tactics and war preparations; they would have no part in them. The protesters informed the police beforehand of their intention to violate the law. When the siren sounded, instead of heading for shelter, the protesters sat on benches in City Hall Park. They were arrested and detained for nine hours before being released on fifteen hundred dollars bail.

When their case came to trial, the protesters made a statement explaining their brazen stance. They said they did not wish to participate in an action aimed only at creating a war mentality. Taking cover from an atomic attack was ridiculous, they said, and they offered their action, and any punishment for it, as a small act of penance for dropping the atomic bomb on Japan. The judge found them guilty but suspended their sentence, so they served no jail time.

For the next four years, Workers along with others continued their protests. They were jailed each time for anywhere from five to thirty days. The Catholic Worker carried accounts of the demonstrations and explained Workers’ rationale for participating. Workers wrote about their own jail experiences and, thus, brought public attention to jail conditions and to the lives of those so confined. In 1960, one thousand people showed up to protest the “war games,” as The Worker dubbed them. When arrests were made, the Workers were passed over, prompting Hennacy to ask one of the arresting officers if he wasn’t shirking his duty. After 1960, the City gave up on its annual air-raid drills.

Slum Landlord

In 1956, Dorothy Day was handed a summons ordering her to appear before a City judge to answer charges of being a slum landlord and of running a firetrap. Since the thirties, The Catholic Worker had run a House of Hospitality, with rooms and beds for those who had no home of their own. The Houses were always liveable, although no one ever worried about conforming to any housing regulations. When Day appeared in court, she explained to the judge that The Catholic Worker was a charitable organization and that the apartments were for those who had no other place to live. “All the more reason for you to provide suitable housing” for them, the judge growled. He fined her $250 and told her that she and her fifty “tenants” would have to vacate in 10 days. Day was stunned.

Someone contacted The New York Times, which picked up the story. Public outcry about the incident caused the judge to apologize to Day, suspend the fine, and give her enough time to raise the $28,000 needed to make the house conform with local building codes. Because of the publicity, within a month most of the funds had been donated and soon the House was refurbished to meet City standards. But “Holy Mother City” had the last word. In 1958, the City informed Day and the Workers that they would have to move to make room for a new subway line!

About Cuba

When Fidel Castro’s revolution in Cuba succeeded in 1959, The Catholic Worker came out on Castro’s side. The paper’s critics were outraged. How could a Catholic paper endorse a government opposed to the Church? Even friends of The Worker were astonished and thought the paper had compromised its pacifist position. Day answered both critics and friends in the article “About Cuba.”

To her critics, Day said:

It is hard … to say that the place of The Catholic Worker is with the poor, and that being there, we are often finding ourselves on the side of the persecutors of the Church. . . . One could weep with the tragedy of denying Christ in the poor. . . . Fidel Castro says he is not persecuting Christ, but Churchmen who have betrayed him (in the poor). . . . (Castro) has said that the Church has endured under the Roman empire, under a feudal system, under monarchies, empires, republics and democracies. Why cannot she exist under a socialist state? He has asked the priests to remain to be with their people….

To her friends, she said:

We are certainly not Marxist socialists nor do we believe in violent revolution. Yet we do believe that it is better to fight, as Castro did with his handful of men … than do nothing. We are on the side of the revolution. We believe there must be new concepts of property, which is proper to man … there is Christian communism and a Christian capitalism as Peter Maurin pointed out. We believe in farming communes and cooperatives and will be happy to see how they work out in Cuba.

The criticisms continued, however, and Day, at age 65, decided to go to Cuba to report first-hand on Castro’s revolution. Her reports were printed in her “On Pilgrimage” column from September through December of 1962. She recounted day-to-day experiences among the Cuban people in a touching way that gave her readers an idea of exactly what was happening to both Church and State in Cuba. Many praised her Cuban reports as her best journalistic work. One admirer wrote simply, “Thank you for your courage on Cuba.” After Day’s personal reports on Cuba, the controversy stopped.

(To Be Continued)

This is Part IV of a series of articles on The Catholic Worker. Click on links for Part I, Part II and Part III.

#Dorothy Day#The Catholic Worker#Ade Bethune#Fritz Eichenberger#civil disobedience#Michael Harrington#The Other America#A Penny A Copy#Robert Ludlow

0 notes

Text

Dorothy Day and her Catholic Workers Didn’t Skimp on the Works of Mercy or the Beatitudes

When Pope Francis I appeared before a Joint Session of the U.S. Congress in September 2015 he mentioned four notable Americans who exemplify the American spirit. Among them—and the only woman—was Dorothy Day. [Abe Lincoln, MLK, and Thomas Merton also got the nod.] Of Day, he said:

In these times when social concerns are so important, I cannot fail to mention the Servant of God Dorothy Day, who founded the Catholic Worker Movement. Her social activism, her passion for justice and for the cause of the oppressed, were inspired by the Gospel, her faith, and the example of the saints.

It was thrilling to hear someone so noteworthy praise Dorothy Day in the same breath as these other “worthies” of American life. Until recently—with a new book and documentary about her—it was rare for the name of Dorothy Day to be mentioned at all.

Pope Francis approaching the podium to address a Joint Session of Congress in September 2015

I know this from my own experience. Since the publication of my book about the civil rights movement in 2013, I’ve had the opportunity to address many an audience and have generally provided the sponsors a summary of my “bio” which always mentions Dorothy Day (along with Dr. King and Mohandas Gandhi) as one of my inspirations. While the other two are well known, Dorothy Day’s name usually prompts blank stares or shoulder shrugs. It seems, though, that perhaps now Day’s time has come. Just as her great mission was taken up during the Great Depression, her “comeback” is happening during the Great Pandemic. There is such need and suffering among our own people today, it is good to have a Dorothy Day to look to for inspiration and hope that if we all pull together, we may just get out of this ditch.

On that point, here is what Pope Francis, during that same speech to Congress, said about politics and its true intent.

Each son or daughter of a given country has a mission, a personal and social responsibility. Your own responsibility as members of Congress is to enable this country, by your legislative activity, to grow as a nation. You are the face of its people, their representatives. You are called to defend and preserve the dignity of your fellow citizens in the tireless and demanding pursuit of the common good, for this is the chief aim of all politics. A political society endures when it seeks, as a vocation, to satisfy common needs by stimulating the growth of all its members, especially those in situations of greater vulnerability or risk. Legislative activity is always based on care for the people. To this you have been invited, called and convened by those who elected you.

Called to seek the “common good”—not just politicians, I might add, but all of us. May we all pull together, work together, as we seek to overcome what undoubtedly is one of the greatest challenges of our lifetimes.

And now, Part III of my series on Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker.

[Click here for Part I and Part II]

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Issues

Initially, The Catholic Worker was viewed as Catholicism’s answer to Communism. Commonweal’s first analysis of The Catholic Worker phenomenon was entitled: “A Catholic Paper vs. Communism.” The Catholic Worker, it said, was a journal established “to offset the polemics of Communism with a clear exposition of the principles of social justice enunciated in papal encyclicals; and to oppose Communism and atheism by fighting for social justice for the working man.”

Indeed, Dorothy Day reveled in the comparison. She used to enjoy recounting the story of how Catholic Workers competed with Communists when selling newspapers on the street corner. When the Communist shouted, “Read The Daily Worker!” a Catholic Worker would retort, “Read The Catholic Worker daily!!”

Under the headline “Specimens of Communist Propaganda,” The Catholic Worker would even debunk some of the more outlandish attacks on the Catholic Church by the Communist press. Its battle against Communism gave The Catholic Worker some degree of respectability in Catholic circles. But when the paper began to strike out at the established bourgeois practices of American Catholicism itself, its reviewers turned sour.

One such attack was directed at the concurrence of Catholic institutions, schools, and hospitals in their policies of racial segregation, as practiced by American society as a whole at the time. “We Have Sinned Exceedingly” was the title of one editorial on the subject.

Another issue on which The Catholic Worker and the Church hierarchy were on opposite sides was the Child Labor Amendment. The Catholic Worker favored the Amendment, which sought to end industry’s use and abuse of children in the workforce. The Church feared that any legislation concerning the lives of children might eventually lead to government interference in the parochial school system.

Because of these and other contentious issues, many Catholics raised questions about how “Catholic” The Catholic Worker really was. The Diocese of New York’s Chancery Office received letters urging the Church to take some action against The Catholic Worker. The head of the Diocesan Office of Censor of Books wrote a letter to Day and later visited the CW offices. His only “action” was to ask that The Catholic Worker find a priest to act as an editorial advisor for the paper to “avoid criticism and … be of assistance to the future development of the work.”

Day gladly accepted this suggestion and asked Father Joseph McSorley, the same priest who had told her not to ask the Church’s permission to publish, to serve as the paper’s advisor. Although she often differed with the hierarchy, Day always tried to obey their wishes. She once said, “If the Cardinal ordered me to stop publishing tomorrow, I would.” Of course, he never did.

Labor

Throughout the thirties, The Catholic Worker kept its focus fixed on the poor and on labor issues. Although Peter Maurin was not interested in furthering Labor’s materialistic gains—“Strikes don’t strike me,” he would say—Day supported organized labor and often picketed with strikers.

During these years, she reported on the Borden Milk Company’s dispute with its deliverymen and asked readers to boycott Borden products. She covered the organization of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union and the New York Seamen’s walkout. The Catholic Worker even provided food and shelter for the striking sailors.

April 1936 edition of The Catholic Worker

Day even interviewed John Lewis, the first president of the Congress of Industrial Organizations; she was in favor of worker unionization. She went to Detroit to help her readers understand the sit-down strike by the United Auto Workers, a CIO affiliate, and to Pittsburg and Johnstown where the CIO was trying to organize the workers of the Bethlehem Steel Corporation.

Toward the end of the 1930s, after Labor had made some major strides, and with the increasing possibility of war in Europe, The Catholic Worker shifted its emphasis to another crucial issue—Peace.

Blessed are the Peacemakers

As early as October of 1933, The Catholic Worker made clear that it was a pacifist paper. It announced it would send delegates to the “United States Congress Against War” to represent “Catholic Pacifism.” Three years later, the Worker started an organization of Catholic conscientious objectors. Workers saw what was brewing in Europe and were determined to be ready “when the next war comes along.” The Catholic Worker’s pacifism was based on spiritual principles:

As long as men trust to the use of force—only a superior, more savage and brutal force will overcome the enemy. We use his own weapons, and we make sure our own force is more savage than his . . . . Today the whole world has turned to the use of force . . . . If we do not emphasize the law of love, we betray our vocation.

The following years of the paper’s history showed just how much love American Catholics had for pacifism. The Spanish Civil War began in 1936, pitting Communist against Catholic. American Catholics revered Generalissimo Francisco Franco and considered his revolution against Communism to be a “holy war.” The Worker refused to take sides and blamed both Communists and Catholics alike for the outbreak of hostilities.

“Catholics who look to Spain to think Fascism is a good thing because Spanish Fascists are fighting for the Church against Communist persecution,” the Worker observed, “should take another look at recent events in Germany to see just how much love the Catholic Church can expect.”

Although many European Catholics agreed with The Catholic Worker’s sentiments, Americans were appalled by its position. Many accused the paper’s editors of being “Communists masquerading as Catholics”—a criticism that would often be leveled against The Catholic Worker in the years to come.

The paper maintained its pacifist stance throughout World War II. It called for massive draft resistance and strikes by those who worked in the war-supporting industries. Pacifist priests wrote articles on the Catholic tradition of conscientious objection. The Worker even ran an alternative service camp in New Hampshire for Catholic conscientious objectors.

The newspaper suffered dramatic losses as a result of its principled stand. In November 1939, the paper’s circulation had grown to about 130,000 monthly. During the next six years, subscriptions steadily declined, especially subscriptions by bishops who had accepted bundled shipments of the paper for sale in their churches. By the end of the war, the paper was reaching only an estimated 50,000 subscribers.

Dorothy Day, Peace Activist

In the face of all manner of criticism, Dorothy Day held out:

We are still pacifists. Our manifesto is the Sermon on the Mount, which means that we will try to be peacemakers. Speaking for many of our conscientious objectors, we will not participate in armed warfare or in making munitions, or by buying government bonds to prosecute the war, or in urging others to these efforts.

The Catholic Worker was, of course, a “voice crying in the wilderness.” Men did not drop their weapoins or refuse to make munitions. The war continued to its horrifying conclusion—Hiroshima. In a column entitled “We Go On Record—” Day wrote bitterly of this historic tragedy:

Mr. Truman was jubilant. President Truman. True man; what a strange name, come to think of it. We refer to Jesus Christ as true God and true man. Truman is a true man of his time in that he was jubilant. He was not a son of God, brother of Christ, brother of the Japanese, jubilating as he did. He went from table to table on the cruiser, which was bringing him home from the Big Three conference, telling the great news; “jubilant” the newspapers said. Jubilate Deo. We have killed 318,000 Japanese.