#1993: demimonde

Text

Interview with The Telegraph (2023)

We all know what is meant by McCarthyism. It popularly refers to the first half of the 1950s, when Senator Joseph R McCarthy led a ruthless campaign to hound suspected communists out of the US government. What’s less well-remembered than the Red Menace is the Lavender Scare: by an executive order from President Eisenhower, McCarthyism also targeted gays and lesbians. “If you want to be against McCarthy, boys,” the senator once told the press, “you’ve got to be either a Communist or a c--ksucker.”

Thus gay men and women, living closeted lives as they worked for the state, were targeted by sinister-sounding bodies: the FBI’s Sex Deviance Investigations Unit, Washington DC police’s Sex Perversion Elimination Program and the Department of State’s M Unit. All sought to identify government employees deemed to be security risks vulnerable to blackmail.

Popular culture lost sight of the Lavender Scare until it was brought into the light in the US by Thomas Mallon’s 2007 novel Fellow Travelers. Set mostly in the early 1950s, it told of a tangled romance between two men; Hawkins “Hawk” Fuller, a handsome war veteran and political fixer who steers clear of emotional attachment until he meets Tim Laughlin, a sweet young Catholic newcomer to DC whom he nicknames Skippy and sets up in the office of a Republican senator.

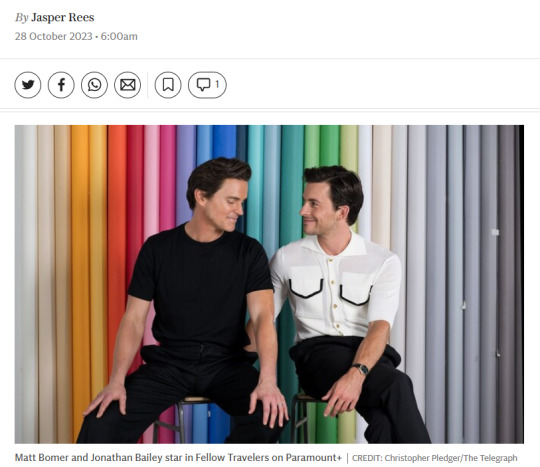

The novel was not published in the UK. But now it has been adapted for television, and one piece of casting in particular feels calculated to get the attention of audiences beyond the US: Laughlin is played by British actor Jonathan Bailey, best known as the Regency heartthrob Anthony, 9th Viscount Bridgerton.

His co-star is the American Matt Bomer, who, like Bailey, professes ignorance of what the New York Times, in its review of the novel, referred to as “the Lavender Hill mob”. “It’s a chapter of LGBTQIA history that I was completely unaware of,” he says.

This is not the first time the novel has been adapted – it was staged as an opera in Cincinnati in 2016. By then it had already caught the attention of Ron Nyswaner, who laboured over bringing the book to the screen for the best part of a decade. Best known for his script for Philadelphia, the 1993 Aids courtroom drama which earned Tom Hanks his first Oscar, it was his stint as a producer of Homeland that persuaded Showtime to fund an expensive eight-part decades-spanning drama. “I’m still in disbelief that we were able to tell this story on the scale that we were able to tell it,” says Bomer, who is also an executive producer on the drama.

The scale is considerable. The period detail of 1950s Washington, in both corridors of power and gay demimonde, is lavishly recreated. And as the story progresses it parts company with the novel, which opens with Hawk looking back at the closure of his career as a diplomat in Tallinn in 1991. Nyswaner’s script expands to take in other pivots in modern US history: the Civil Rights movement, the Vietnam War, and the spread of Aids in the 1980s, when the now-married Hawk and the dying Laughlin meet for a final reckoning.

I met the drama’s two stars in London earlier in the summer, before the actors’ strike in Hollywood put a stop to such encounters. It was the first time they’d seen each other since the end of the shoot. Bomer, though just off the plane and heavily jet-lagged, exudes a chiselled, blue-eyed intensity. Bailey fizzes with puppyish energy. Both are themselves gay and Bailey in particular sees their casting as a sign of progress. “We would not be playing these parts five or 10 years ago,” he says. The highlights of his CV are mix and match. He has played mainly straight characters on television in the likes of Broadchurch, Crashing and W1A, and gay characters on stage in the Sondheim musical Company and Mike Bartlett’s play C--k in the West End.

The career of Bomer, 10 years his senior, looks a little more linear. His most high-profile film role is as an object of ladies’ lust in male-strippers drama Magic Mike and its sequel. But in 2014 he won a Golden Globe playing a closeted journalist in HBO’s adaptation of Larry Kramer’s play The Normal Heart. In 2018, he made his Broadway debut as part of an exclusively gay cast reviving The Boys in the Band, a portrait of gay life in 1960s New York.

Earlier on the day we met, Stanley Tucci had said on Desert Island Discs that he doesn’t see why straight actors shouldn’t play gay characters. “I think it’s incredibly complicated and nuanced,” says Bailey with a sigh. “You just want to make sure that everyone feels there’s enough space at the table. Everyone who is panicking that they’re never going to be able to play outside their own experience is wasting their energy.”

Bomer counters that it ought to cut both ways, that gay actors should be allowed to play straight. He speaks darkly of movie producers who “wouldn’t hire me because of who I was”, of gay actors who “weren’t even given a shot. A lot of it boils down to opportunity. Was everyone given the opportunity for the role? There is something about seeing the most authentic version of who you are represented on screen. It gives you hope.”

In Fellow Travelers that authenticity is portrayed most unswervingly in the bedroom, which the plot requires Hawk and Laughlin to visit often. “I haven’t necessarily really seen gay intimacy in a way that I would want to,” says Bailey. I gently remind him of Linus Roache, who plays a senator in Fellow Travelers but, back in 1994, starred in Jimmy McGovern’s Priest as a Catholic priest struggling with his sexuality – graphically so in a central scene with Robert Carlyle. “Oh yeah, that’s true,” he says. “I looked to that a lot.”

As is on trend for male actors nowadays, both leads look impeccable with their shirts off in low honeyed lighting. “Hawk is ex-military and he also wants to appeal to people in bathroom stalls,” reasons Bomer, who did period-appropriate Royal Canadian Air Force drills and looks no less pneumatic than he did in Magic Mike.

Bailey concedes that Laughlin, who orders milk the first time we meet him, boasts the body of a Greek god for the simple reason that the shoot overlapped with Bridgerton (yes, he confirms, the newly married Anthony is back for the third season). “There’s no way Tim would have had a Bridgerton body, but what can you do if you’re commuting? I was like, I really want to lose weight to tell Tim’s story, but I lost fat and just got really ripped.”

How resonant is the history portrayed in Fellow Travelers to today? It’s easy to play six degrees of separation between now and then. For instance, McCarthy’s closeted sidekick Roy Cohn is a lead character (played here by Will Brill). A ferocious prosecutor of both communists and gays, he would go on to be Donald Trump’s lawyer, before dying of complications from Aids. It was Trump’s three appointees to the Supreme Court who this summer enabled a 6-3 ruling releasing businesses and organisations from the obligation to treat same-sex couples equally. The landmark ruling occurred just days before I met the actors, and has been widely interpreted as a profound attack on LGBT rights.

“There is an entire generation of men and women who suffered and struggled and loved under a government that felt that its morals were more important than their personal freedoms,” says Bomer. “And that’s exactly what we see happening today. Whether it’s McCarthy or the current Supreme Court justices, are morals more important than freedoms?”

Source

#fellow travelers#jonathan bailey#matt bomer#the telegraph interview#interviews:2023#jonny bailey#interviews#NEW!

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Border Radio”: Where Punk Lived

Some years back, I wrote notes for the Criterion Collection’s edition of Allison Anders’ first feature Border Radio for the Criterion Collection. Tomorrow (June 3), Allison will gab about punk rock with John Doe, Tom DeSavia, and my illegitimate son Keith Morris at the Grammy Museum in L.A. in observance of the publication of the book we’re all in, More Fun in the New World (Da Capo).

**********

“You can’t expect other people to create drama for your life—they’re too busy creating it for themselves,” a punk groupie says at the conclusion of Border Radio. And the four reckless characters at the center of the film certainly manage to create plenty of drama for themselves. In the process, they paint a compelling picture of the Los Angeles punk-rock scene of the 1980s: what it was like on the inside—and what it was like inside the musicians’ heads.

Border Radio (1987) was the first feature by three UCLA film students: Allison Anders, Kurt Voss, and Dean Lent. The subsequent work of both Anders and Voss would resonate with echoes from Border Radio and its musical milieu. Anders’s Gas Food Lodging (1992), Mi vida loca (1993), Grace of My Heart (1996), Sugar Town (1999), and Things Behind the Sun (2001) all draw to some degree from music and pop culture. (She quotes her mentor Wim Wenders’s remark about making The Scarlet Letter: “There were no jukeboxes. I lost interest.”) Voss, who co-wrote and codirected Sugar Town, also wrote and directed Down & Out with the Dolls (2001), a fictional feature about an all-girl band; and in 2006, he was completing Ghost on the Highway, a documentary about Jeffrey Lee Pierce, the late vocalist for the key L.A. punk group the Gun Club.

The three filmmakers met at UCLA in the early eighties, after Anders and Voss had worked as production assistants on Wenders’s Paris, Texas. By that time, Anders and Voss, then a couple, were habitués of the L.A. club milieu; they favored the hard sound of such punk acts as X, the Blasters, the Flesh Eaters, the Gun Club, and Tex & the Horseheads. The neophyte writer-directors, who by 1983 had made a couple of short student films, formulated the idea of building an original script around a group of figures in the L.A. punk demimonde.

Border Radio—which takes its title, and no little script inspiration, from a Blasters song (sung on the soundtrack by Rank & File’s Tony Kinman)—was conceived as a straight film noir. Vestiges of that origin can be seen in the finished film. Its lead character bears the name Jeff Bailey, also the name of Robert Mitchum’s doomed character in Jacques Tourneur’s 1947 noir Out of the Past; its Mexican locations also reflect a key setting in that bleak picture. One sequence features a pedal-boat ride around the same Echo Park lagoon where Jack Nicholson’s J. J. Gittes does some surveillance in Roman Polanski’s 1974 neonoir Chinatown; Chinatown itself—a hotbed of L.A. punk action in the late seventies and early eighties—features prominently in another scene. Certainly, Border Radio’s heist-based plot and the multiple betrayals its central foursome inflict upon each other are the stuff of purest noir. But the film diverges from its source in its largely sunlit cinematography and its explosions of punk humor; Anders, Voss, and Lent also abandoned plans to kill off the film’s lead female character.

In casting their feature, the filmmakers turned to some able performers who were close at hand. The female lead was taken by Anders’s sister Luanna; her daughter was portrayed by Anders’s daughter Devon. Chris, Jeff’s spoiled, untrustworthy friend and roadie, was played by UCLA theater student Chris Shearer.

The directors considered another student for the lead role of the tormented musician, Jeff, but Anders, in an inspired stroke, suggested Chris D. (né Desjardins), whose brooding, feral presence animated the Flesh Eaters. After being approached at a West L.A. club gig and initially expressing surprise at the filmmakers’ desire to cast him, the singer and songwriter signed on, and he helped recruit the other musicians in Border Radio. (A cineaste whose criticism often appeared in the local punk rag Slash, Desjardins would later write an authoritative book on Japanese yakuza films and write and direct the independent vampire film I Pass for Human. He is currently a programmer at the Los Angeles Cinematheque.)

John Doe, bassist-vocalist for the celebrated L.A. punk unit X, and Dave Alvin, guitarist and songwriter for the top local roots act the Blasters, had both played with Chris D. in an edition of the Flesh Eaters. Doe—taking the first in a long list of film and TV roles—was cast as the duplicitous, drunken rocker Dean; Alvin makes an entertaining cameo appearance, essentially as himself, and wrote and performed the film’s score.Texacala Jones, frontwoman for the chaotic Tex & the Horseheads, does a hilarious turn as Devon’s addled babysitter. Iris Berry, later a member of the raucous all-female group the Ringling Sisters, portrays the self-absorbed groupie whose observations frame the film.

Julie Christensen, Desjardins’ vocal partner in his latter-day group Divine Horsemen (and, for a time, his wife), essays a bit part as a club doorwoman. Seen in walk-ons are such local rockers as Tony Kinman, Flesh Eaters bassist Robyn Jameson, and punk hellion Texas Terri. The Arizona “paisley underground” transplants Green on Red and the local glam-punk outfit Billy Wisdom & the Hee Shees were captured in live performance. Those seeking punk verisimilitude could ask for nothing more.

Border Radio had a torturous, piecemeal production history worthy of John Cassavetes. Shooting took place over a four-year period, from 1983 to 1987. Begun with two thousand dollars in seed money, supplied by actor Vic Tayback, the film scraped by on money given to Voss upon his 1984 graduation from UCLA, a loan from Lent’s parents, and cash and film stock cadged here and there. Violating UCLA policy, the filmmakers cut the film at night in the school’s editing bays, where Anders’s two young daughters would sleep on the floor.

The film’s lack of a budget forced Anders, Voss, and Lent to shoot entirely on location; this enhanced the work, as far as the filmmakers were concerned, since they sought a naturalistic style and look for the feature. Lent’s Echo Park apartment doubled as Jeff’s home, while Anders and Voss’s trailer in Ensenada served as his Mexican hideout. The storied punk hangout the Hong Kong Café (whose neon sign can be seen fleetingly in Chinatown) was utilized, as were the East Side rehearsal studio Hully Gully, where virtually every local band of note honed their chops, and the music shop Rockaway Records (one of the few punk stores of the day still around).

Befitting the work of film students on their maiden directorial voyage, Border Radio evinces the heavy influence of both the French new wave of the sixties and the New German Cinema of the seventies. The confident use of improvisation—the cast is credited with “additional dialogue and scenario”—recalls such early nouvelle vague works as Breathless. The ongoing “interview” device immediately recalls Jean-Pierre Léaud’s face-to-face with “Miss 19” in Jean-Luc Godard’s Masculin féminin, while Shearer’s shambling comedic outbursts are reminiscent of the sudden madcap eruptions in François Truffaut’s early films. The work of the Germans is felt most in the great pictorial beauty of Lent’s black-and-white compositions; certain striking moments—a languid, 360-degree pan around Ensenada’s bay; an overhead shot of Chris’s foreign roadster wheeling in circles in a cul-de-sac—summon memories of Wenders’s and Werner Herzog’s most indelible images. (Lent would go on to work as a cinematographer on nearly thirty pictures.)

Though the styles and effects of these predecessors are on constant display, Border Radio moves beyond simple imitation, thanks to a sensibility that is uniquely of its time, spawned directly from the scene it depicts so faithfully. Though putatively a “music film,” very little music is actually on view in the picture; mere snatches of two songs are actually performed on-screen. The truest reflection of the period’s punk ethos can be found in the restlessness, anger, self-deception, and anomie of its Reagan-era protagonists.

In Border Radio, one can see what punk rock looked like, all the way to the margins of the frame: in the flyers for L.A. bands like the Alley Cats, the Gears, and the Weirdos taped in a club hallway, in the poster for Andy Warhol’s Frankenstein and the calendars of L.A. repertory movie houses tacked on apartment walls, in the thrift-store togs and rock-band T-shirts (street clothes, really) worn by the players. But, more importantly, the shifting tragicomic tone of the film, the energy and attitude of its musician performers, and the uneasy rhythms of its characters’ lives present a real sense of the reality of L.A. punkdom in the day.

Put into limited theatrical release in 1987, by the company that distributed the popular surf movie Endless Summer—a film that offers a picture of a very different L.A.—Border Radio was not widely seen and later received only an elusive videocassette release through Pacific Arts (the home-video firm founded, ironically enough, by Michael Nesmith of the prefab sixties rock group the Monkees). With this Criterion Collection edition, the film can finally be seen as the overlooked landmark that it is: possibly the only dramatic film to capture the pulse of L.A. punk—not as it played, but as it felt.

(Thanks to Allison Anders for her invaluable contributions.)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tagged by @demimonde-quasigoddess! Thanks for the tag, I LOVE doing these things. :D

Nickname(s): Acey, Rainbow, Ace

Gender: Female

Star Sign: Aquarius

Height: 5′4″ (and a half tho)

Time: 12:14 AM

Birthday: February 18th, 1993

Favorite Bands/Artist: They Might Be Giants, obviously.

Song Stuck In My Head: Tractor by TMBG. GOOD JAM.

Last Movie I Watched: Space Jam, with my crush, on our first Official Date! I had never seen it before, and I found it incredibly silly and super fun. :D

Last TV Show I Watched: Steven Universe. I am nothing if not predictable.

What I Post: Fandom bullshit, shitposts, selfies, sometimes original Content (TM) but yeah.

Do I Get Ask: what

URL Meaning: damara megido is my trash wife, and also me,

Average Hours of Sleep: Oh God it varies so wildly

Nationality: MURRICA. I apologize for our so-called “president.”

I tag @carcino-geneticists, @aradiiaa, @whokilledcecilpalmer, @imgoingtofavourdisastrous, @artonelico, and anyone else who wants to do it! No pressure tho c:

8 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Pet Shop Boys - West End Girls

Unreal City, under the brown fog of a winter dawn. Earth hath not anything to show more fair. Dirty old river, must you keep rolling, flowing on into the night. London – the lifeblood of the country and the vampire that sucks it back up.

Among other teenage favourites such as George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty Four and the Guinness Book of British Hit Singles, the Eyewitness Guide to London was a library staple. Before the age of seventeen I never made the trip on the route of the Flying Scotsman down to King’s Cross; in fact, bar a school coach trip to Dover en route to France, I’d never been further south than Matlock. But there I was, lying on my bed, fitting Monopoly streets into the A to Z, memorising the names of the boroughs and their railway stations. I was doing what probably thousands if not millions of ‘provincial’ Britons had done before me, embarking on a love-hate relationship with a city I’d never seen.

I finally made the journey on a school trip in 1998. The A-level art students headed off to the National Gallery; I visited UCL with a friend, had a slice of overpriced pizza for lunch in Leicester Square, then reconvened with the English lit students to see Othello at the National. It was sticky hot, and I felt disappointed for most of the time. It was almost worse to come to London for one day, and not get to do or see any of the things on my list, than never go at all. The schedule was so overdetermined I had no time to gawp at the tube posters or read the blue plaques, no time to catch myself realising I’d jumped through the rabbit hole into Wonderland. But then, post-play, we had to cross Waterloo Bridge. The skyline shimmered into focus, St Paul’s ghostly with floodlight, the river lapping against the Embankment. I’ll be back, I said to myself, and a blood-rush flushed me all over. London isn’t a city of instant epiphanies. You don’t see it and die; it can be ugly and gawky, ill-assembled and unphotogenic. But there are always clicks; joints snapping into place; gear shifts. That moment on the bridge was one such: like a photographic print gradually darkening in the developing fluid, London was emerging.

Listen carefully to the opening of ‘West End Girls’ and this is exactly what you hear: London flickering into life, beginning to glitter through the fog. It’s morning, and someone walks into the light from the Paddington concourse. Their heels take to the wet pavement, and their heart beats faster as they scour the street for a taxi. The pulse begins to assert itself, and then the synth string chords – those chords – dark, cool and grand, clean and sleek as a black cab. And a pause, ever so slight, before the new arrival decides to walk; to take in the rush on foot, buoyed airily by the Pet Shop Boys’ smooth minimalism, slinking through the crowds. It’s all there in the video, as a rapid montage of random faces gives way to Neil and Chris, who take to their heels in a vaporous, ghostly Soho, like sombre night-watchmen coming off shift. ‘West End Girls’ is the sound of London settling into focus. Eight million people waking up to the distant rumble of tubes and screech of buses; eight million people rubbing their eyes as the greatest synth bassline in eighties pop music rings out from their clock radios.

It must have been quite an awakening, back then in 1985. It seemed to arrive fully-formed; not just a song, but an aesthetic (though the original Bobby Orlando version from the previous year proves how crucial Stephen Hague was in realising the song’s latent atmospheres). This was not the barroom and dog-track London of Ian Dury, nor was it the hazy, romanticised cityscape of The Kinks. Tennant and Lowe are, of course, northerners, and thus outsiders, though they don’t so much crash the party as float spectrally in a corner with a martini and a raised eyebrow. When the Boys first broke into the charts, much was made of Tennant’s former career at Smash Hits, the foremost evidence cited for his apparently ‘ironic’ take on pop. But I’ve often thought that the beautiful balance they strike between the knowing and the credulous is the product of northern eyes surveying southern landscapes. They are detached, perhaps even sceptical at times; but there’s also that Eyewitness Guide in the bedroom, a city learned and loved, an excitement at having gone through the portals at King’s Cross and slipped into the anonymity of the throng. Despite Tennant having said on more than one occasion that ‘West End Girls’ was inspired by The Waste Land – ‘too many shadows, whispering voices’ is a true summary of Eliot’s fractured epic indeed – the song is too stimulated by what’s going on around it to be either a lament for the lost or a prophecy of doom. It does sound dangerous – there’s something dark and doleful in that bass – but it’s the kind of danger that makes you feel alive and adrenalized. It’s determined to keep its cool, determined not to spend its money all at once; but despite this caution, it’s still the sound of two northerners who will never quite fail to wonder at their adopted home.

It’s a dichotomy embodied by the Boys themselves: arty, askance Tennant, asking questions and pondering significances, and hedonistic Lowe (you can take the lad out of Blackpool!), disappearing into the massed bodies of the rave or shopping incognito at the record exchanges (check out the 1989 B-side, ‘One of the crowd’, Chris’s very own credo). It’s why their songs at their finest have such cross-cultural appeal; the Guardianista manifesto of ‘Che Guevara and Debussy to a disco beat’ (‘Left to my own devices’) can coexist quite happily with the football terrace reworking of gay utopianism (their definitive cover of ‘Go West’, which was taken on in earnest by Arsenal supporters). It’s what makes them so English, yes (another epithet interviewers and critics find impossible to avoid), but more than that, it’s what makes them so London, and more specifically Northern and London. In no other city in the world do you get quite so many disparate people rubbing shoulders in the crush; underfunded social housing and potholes on one side of the street, while the opposite side gleams with stucco and swept pavements. This is the world the Boys both celebrate and lament, and often with an emphasis on the relationship between regionalism and metropolitanism. It’s mourned in ‘King’s Cross’ (the station from which Geordies spill out into the city like foaming brown ale from a broken bottle), and especially ‘The Theatre’, which again makes specific reference to expats from beyond the Watford Gap (‘Boys and girls come to roost / From Northern parts and Scottish towns / Will we catch your eye?’) But then there’s the funny B-side ‘Sexy Northerner’, about a guy who takes the capital by the scruff and recasts it in his own image. London is always up for grabs, and the Boys will be there as the daybreak traffic hits, on through lunch at the office, then dinner, pub, club, and into the demimonde of the dead hours. You always wanted a lover, I only wanted a job. You wait till later, till later tonight…

You see, London is all about almost unlikely juxtapositions, and the Pet Shop Boys pull off some of the unlikeliest. The astonishing ‘Dreaming of the Queen’ (perhaps the most moving song they have ever written) is the most surreal. It’s an elegy for the AIDS dead (‘there are no more lovers left alive’) sung by ‘Lady Di’, whose own marriage is failing; the ‘Queen’ of the title is both the monarch Neil visualizes in his dream, chastising him for being in the nude, and, perhaps, the patron saint of all ‘queens’ everywhere who are traumatized by the epidemic. It’s timely – on release in 1993, all these events were highly topical – and timeless, commenting on the ways in which our subconscious finds its own warped logic to deal with the crushing events of history. And then that heartbreaking line, ‘Yes, it’s true / Look, it’s happened to me and you’ (a rejoinder to an earlier AIDS lament, ‘It couldn’t happen here’). London is a place in which ‘big’ history is made all around us, in which we constantly rub up against grand monuments and memorials; it’s also a place that can find space for the ‘me and you’. At its best, Tennant and Lowe’s songwriting focuses through both of these lenses. Remember ‘Shopping’, seemingly a deadpanned celebration of the personal benefits of the credit boom, but actually a broadside against Thatcher’s privatisations? No eighties band was better at defining the emptiness of consumerist luxury than the Pet Shop Boys, and I’m not just talking about the immortal ‘I’ve got the brains, you’ve got the looks, let’s make lots of money’. Stick on the original version of ‘I want a dog’, and marvel at the boredom of desire; the blank-eyed intonation of ‘oh, you can get lonely’; the killer couplet ‘Don’t want a cat / Scratching its claws all over my habitat’, expressing withering disdain for any mog that ruins Terence Conran’s finest.

In ‘West End Girls’, of course, there are cats and dogs, paws and claws. The greyhounds of Walthamstow (east end boys) and the Persian princesses of Kensington (the girls of the title). Another great juxtaposition, and one that makes London sexy in a constantly surprising way. All sorts of mythologies catch each other’s eyes on the escalators. The Kray brothers lock stares with Charlotte Rampling; there’s a frisson of sexual danger, a possibility of pugilism. But London has to brook its own contradictions in order to survive. It surfs breezily above them, just as the track itself is both shiny and seamy, dark and light. The song is all tensions: African and European (the jazzy trumpet and rich gospel backing vocalist knocking against Tennant’s high white plaint), passive and active, dispassionate and yet full of deep, deep yearning; yet it’s miraculous how these coexist with such effortless panache. These are the frictions of all great British pop, but seldom do they ever sound so exotic and lush. The Pet Shop Boys really did change the game; this is a London both real and imagined, both as good as the real thing and somehow even better. It’s not surprising that it was number one all over the world, including America, and no accident that it even featured prominently in the Olympic shebang last year.

You see, for all the expert satire, it’s easy to forget that the Pet Shop Boys are still actually in love with London, and that its allure will never pall. ‘We’ve got no future, we’ve got no past’, intones Neil in the last verse. In London, you can be someone different every day, ventriloquizing the people around you, learning to walk to their gait; only the present, and your presence matter. Just to be there at all; to be swimming in the tide. East End boys will always chase West End girls, and perhaps vice versa. Northerners and foreigners will always be both repelled and fascinated by the Unreal City. As long as London exists, so will ‘West End Girls’; so will a thousand teenagers from elsewhere dreaming in their bedrooms about ‘running down, underground, to a dive bar in a West End town’. As T.S. Eliot would have it, we shore these fragments against our ruin. Or else, we save ourselves with the power of a synth bass, a crunchy snare and the ecstasy of urban romance.

19 notes

·

View notes

Link

Artists: G.B. Jones, Paul P.

Venue: Cooper Cole, Toronto

Exhibition Title: Temple of Friendship

Date: August 26 – October 3, 2020

Click here to view slideshow

Full gallery of images, press release and link available after the jump.

Images:

Images courtesy of Cooper Cole, Toronto

Press Release:

Cooper Cole is pleased to present Temple of Friendship, an exhibition of collaborative work by G.B. Jones and Paul P.

In their independent practices, both Jones and P. are well recognized as drafts-people who appropriate and reposition figurative images from queer history. Devoted to the act of archiving, as both a tool and a creative conceit, they have, over the past 18 years, assembled an oeuvre of collaborative cut-and-paste collages from their copious image banks. The exhibition is titled after Natalie Barney’s so-named Neoclassical folly situated in her Paris courtyard, in which she hosted a salon for the queer demimonde in the years before the First World War.

Jones and P. are interested in ungovernable sexualities and genders, and in the history of aesthetics forged by those who were compelled to communicate and represent themselves through innuendo and codes. While their collages dwell on the queer lineage of coded language in aesthetics and attitudes, they also posit the violent and retaliatory potential of these protagonists, utilizing images and references relating to riots in Toronto precipitated by police violence: in particular, those around the bathhouse raids in 1980, and during the G20 summit in 2010. Jones and P.’s mesh of uneasy images illustrate the immemorial (and still applicable) arc of their protagonists, whether anonymous and symbolic, infamous or famous. Out of the hostile climate of youth, their inchoate anger and longing drives them underground to places where pathos and wonder mix, after which they emerge self-aware and defiant; shocking, dazzling, confusing. Symbols of invention within a world of manipulation.

Temple of Friendship follows Born Yesterday, Jones and P.’s solo exhibition at Participant Inc., New York, in 2017.

G.B. Jones (b. 1965 Bowmanville, Ontario, Canada) has acquired international acclaim for her super-8 films, zines, and proto-Riot Grrrl band Fifth Column. Active since the early 1980s, her works are milestones in independent film, publishing, and art rock, respectively, and primary sources for what later became known as Queercore. Concurrently, Jones has always been a dedicated visual artist best known for all-female reprises of Tom of Finland’s drawings. By a simple twist, hers are images of liberation freed of the fascist tendencies at work in gay male culture. Her solo exhibitions include Cooper Cole, Toronto, 2018; Tom Of Finland, G.B. Jones, Daniel Buchholz, Cologne, 1993; Feature, New York, 1991. Her work has been included in numerous group exhibitions including: Art After Stonewall, Grey Art Gallery and Leslie-Lohman Museum, New York, 2019; Coming to Power: 25 Years of Sexually X-Plicit Art by Women, Maccarone, New York, 2016; This Will Have Been: Art, Love and Politics in the 1990s, Museum of Contemporary Art, 2012; Coming To Power: 25 Years Of Sexually X-plicit Art By Women, David Zwirner, New York, curated by Ellen Kantor, 1993. Jones lives and works in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Paul P. (b. 1977, Canada), who first came to attention in the early 2000s, has developed a wide- ranging practice centered on a series of drawings and paintings of young men appropriated from pre-AIDS gay erotica. His solo exhibitions include Morena di Luna/Maureen Paley, Hove, UK (2020); Queer Thoughts, New York, USA (2019); Lulu, Mexico City, Mexico (2019); Scrap Metal, Toronto, Canada (2015); and The Power Plant, Toronto, Canada (2007). His group exhibitions include Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (2014); Les paris sont ouverts, Freud Museum, London (2011); and Compass in Hand, Museum of Modern Art, New York (2009). P.’s work is in the collections of the National Gallery of Canada, the Museum of Modern Art New York, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Hammer Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Art Gallery of Ontario, and the Whitney Museum, among others.

Paul P. wishes to acknowledge the generous support of the Ontario Arts Council.

Link: G.B. Jones, Paul P. at Cooper Cole

The post G.B. Jones, Paul P. at Cooper Cole first appeared on Contemporary Art Daily.

from Contemporary Art Daily https://bit.ly/2R6Hkj3

1 note

·

View note

Text

Noticias de series de la semana: Recordemos acosos antiguos

Acoso en The Wonder Years

Alley Mills, la que interpretara a Norma Arnold en Aquellos maravillosos años, nos ha recordado que una diseñadora de vestuario acusó en marzo de 1993 a Fred Savage y Jason Hervey (Kevin y Wayne en la serie) de constante acoso verbal y físico, en una demanda en la que también acusaba a varios productores y a los padres de Savage, y que ésta fue la razón de la cancelación. Añade en la entrevista que Savage es la persona más dulce y maravillosa de la Tierra, que la demanda fue ridícula y que este tipo de acusaciones -según ella- falsas pueden darse también ahora. [Fuente]

Noticias cortas

CBS ha encargado un episodio más para la segunda temporada de MacGyver, haciendo un total de veintitrés.

El miércoles 31 de enero se reanudó la producción de la sexta y última temporada de House of Cards.

Neil Patrick Harris (Olaf) confirma que la tercera temporada de A Series of Unfortunate Events será la última.

Renovaciones de series

Netflix ha renovado Fuller House por una cuarta temporada

Syfy ha renovado Happy! por una segunda temporada

Netflix ha renovado Suburra por una segunda temporada

USA Network ha renovado Suits por una octava temporada

Showtime ha renovado The Chi por una segunda temporada

BBC One ha renovado Death in Paradise por una octava temporada

Cancelaciones de series

Hulu ha cancelado Shut Eye tras su segunda temporada

Showtime ha cancelado Dice tras su segunda temporada

DIncorporaciones y fichajes de series

Diane Lane (Unfaithful, Under the Tuscan Sun) y Greg Kinnear (As Good As It Gets, Little Miss Sunshine) se unen a la sexta y última temporada de House of Cards. Interpretarán a dos hermanos pero no se conocen más detalles.

Katherine Heigl se une como regular a la octava temporada de Suits. Será Samantha Wheeler, una nueva socia del bufete.

Sofia Carson (Descendants) participará en varios episodios de la segunda temporada de Famous in Love interpretando a Sloane, la hija de un magnate del cine. Además, se une al piloto de The Perfectionists, el spin-off de Pretty Little Liars, como Ava, blogger de moda.

Ernie Hudson (Ghostbusters, Grace and Frankie) será el padre de Syd (Gabrielle Union) en el spin-off de Bad Boys.

Jeff Pierre (Beyond, Shameless) será recurrente como el príncipe Naveen en la séptima temporada de Once Upon a Time.

John Ortiz (The Guest Book, Togetherness), Tomer Sisley (La commune, Les innocents) y Mehdi Dehbi (Tyrant) protagonizarán Messiah.

Candis Cayne (The Magicians, Dirty Sexy Money) participará en varios episodios de Grey's Anatomy interpretando a una paciente transexual sometida a una vaginoplastia.

Stephanie Arcila (Mariposa de barrio) y Erin Carufel (The Lincoln Lawyer) serán recurrentes en Here and Now. Se desconocen detalles.

Tembi Locke (Eureka) será recurrente en la novena temporada de NCIS: LA como Leigha Winters, ejecutiva de un banco de inversión.

Shamikah Christina Ramirez será recurrente en la segunda temporada de Superior Donuts como Tavi, nuevo interés amoroso de Franco Wicks (Jermaine Fowler).

Robert Klein (The Mysteries of Laura) sustituirá a Alan Arkin como Martin, padre de Grace (Debra Messing), en Will & Grace.

Dulé Hill (Alex) ha sido ascendido a regular de cara a la octava temporada de Suits.

Eddie Steeples (Eddie) será regular en la segunda temporada de The Guest Book. Carly Jibson (Vivian) también vuelve.

Pósters de series

Nuevas series

Luz verde directa en HBO a Demimonde, creada por J.J. Abrams. Número de episodios por determinar.

Bravo encarga dos temporadas de una antología true crime basada en artículos y podcasts del L.A. Times. La primera, escrita por Alexandra Cunningham (Desperate Housewives, Chance), contará la historia del estafador John Meehan, conocido como Dirty John.

Luz verde directa a Metropolis, precuela de Superman, en el nuevo servicio digital de DC. Creada por John Stephens (Gotham, The O.C.) y Danny Cannon (Gotham, CSI), seguirá a Lois Lane y Lex Luthor.

Tomorrow Studios prepara The Chemist, adaptación de la novela de Stephenie Meyer (Twilight) sobre una mujer que es uno de los secretos más oscuros de una agencia del gobierno norteamericano tan clandestina que no tiene nombre y se convierte en el objetivo de los que hasta ahora le daban trabajo.

Michael Haneke (Amour, Funny Games) desarrolla Kelvin's Book (10 episodios), drama distópico sobre un grupo de jóvenes que se ven obligados a aterrizar fuera de su país de origen y por primera vez se enfrentan con la verdadera cara de su nación.

NBC encargad diez episodios de The Gilded Age, de Julian Fellowes (Downton Abbey, Gosford Park), sobre las nuevas fortunas en Nueva York a finales del siglo XIX.

Netflix encarga dieciséis episodios de The Prince of Peoria, comedia de Nick Stanton y Devin Bunje (Gamer's Guide to Pretty Much Everything) sobre un príncipe de 13 años que viaja a Estados Unidos para vivir de incógnito como estudiante de intercambio y se hace amigo de un estudiante brillante y molesto que es totalmente opuesto a él.

Fechas de series

On My Block llega a Netflix el 16 de marzo

Alexa & Katie llega a Netflix el 23 de marzo

Tráilers de series

The Rain

youtube

Jack Ryan

youtube

Suits - Temporada 7b

youtube

Castle Rock

youtube

On My Block

youtube

Station 19

youtube

Rise

youtube

0 notes

Text

GIUSEPPE VERDI’S LA TRAVIATA AT LA SCALA, MARCH 3, 2017

The creative team behind this Traviata comes with a considerable body of work as far as cinema is concerned. Back in 1974, Liliana Cavani directed Il portiere di notte. A classic. (I haven't seen it yet, so that's all I can say). Dante Ferretti and Gabriella Pescucci (production and costume designer respectively) are responsible for a great deal of filmed imagery. Just a great deal. They won Oscars. They worked together on The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988) and The Age of Innocence (1993). Dante Ferretti is known as Martin Scorsese's designer of choice; as of now, they're riding a nine-picture streak. Gabriella Pescucci worked on TV series too, such as The Borgias (in case you're wondering: the Jeremy Irons one—not John Doman) and Penny Dreadful. What was the night like then? Unexciting and plain are the first words I'd use. Each part was given a label/signal in the form of a color. White for the great party where Alfredo (already in love for some time, but from a distance) is finally introduced to Violetta. A warm, cozy ocher for Alfredo and Violetta's country getaway. Red for the second, entirely different great party (to signify sin and drama). Green for Violetta's room: a sort of dim cave where people can retreat and, well, die. That's it pretty much. Both the masterplan and its execution were plagued by stiffness. And that stiffness turned La traviata into a strangely polarized object.

There were basically two big scenes: Violetta's extensive soliloquy at the end of Act I («È strano!… Ah fors'è lui che l'anima… Follie! Follie!… Sempre libera degg'io») and Violetta's death. Everything else—and I mean everything: environment, characters, events—was merely a filler, a totally forgettable bridge between the only places that mattered. (It could be argued that Alfredo Germont and Giorgio Germont may in fact deserve such a cruel fate. Still…). Utter stiffness did apply to the cast too, with the lone exception of Ailyn Pérez as Violetta Valéry. She sounded comfortable during the two big scenes I mentioned (even if I wouldn't praise the way she read the letter); yet if you think of what Violetta could/should be, I'm positive something got lost. (It was essentially a sweet, kindhearted dame. The enigmatic little girl whose seductive power can dominate a whole demimonde of barons, marquises, super-rich bourgeois etc. was nowhere to be found). Nello Santi and the orchestra couldn't overcome the weaknesses I've tried to describe; nevertheless, their unhurried and somewhat darkening style was decidedly enjoyable. (The ending felt like Salome. And I was fascinated by the very first bars of the Prelude. While the violins in the higher register were nothing short of sublime, the entrance of the triple-meter accompaniment to the melody of «Amami, Alfredo» was deliberately cheap and mechanical: the perfect imitation of some old street organ. I think it's the kind of music Lou Reed must have been hearing while he was drinking sangria in the park, in that ravishing song of his).

0 notes