#Dmitry Pevtsov

Text

Made in the USSR (May Day 2023)

A man sporting a “Made in the USSR” tattoo, Liteiny Prospect, Petersburg, May 1, 2023. Photo by Vadim F. Lurie, reproduced here with his kind permission

Victory Day is a memorable holiday for every citizen of St. Petersburg! During the celebration of the Great Victory, each of us remembers the heroic deeds of our grandfathers. In keeping with a long-established tradition, many musicians dedicate…

View On WordPress

#Alexander Bastrykin#Alexei Gorinov#Alexei Navalny#Arkady Kots (band)#Dmitry Pevtsov#Ella Pamfilova#Fyodor Chistyakov#Georges Moustaki#Kirill Medvedev#LDPR#Lensovet Palace of Culture#Lev Schlosberg#May Day#Mediazona#Minecraft#permanent revolution#pobedobesie (victory frenzy)#post-Soviet nostalgia#re-Sovietization#Runet#Russian Central Election Commission#Russian Constitution#Russian courts#Shavkat Mirziyoyev#Uzbekistan#Vadim Lurie#Vladimir Zhirinovsky#Yabloko

0 notes

Text

According to Russia’s propaganda outlets, one of the goals of Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine is to fight back against the "sexual permissiveness" and “moral decay of the West." Since the war began, Russian politicians and pro-government news net have flooded the airwaves with stories about the “depravity” of the Ukrainian army, repeatedly equated homosexuality with pedophilia, and presented Russian troops as heroes fighting for “traditional values.” But however absurd this rhetoric may be, it’s not new or unique: throughout history, these same ideas have repeatedly arisen in a variety of dictatorships, from Hitler’s Germany and Stalin's Russia to Gambia and Uganda in the 21st century. Meduza explains why authoritarians on both the right and the left can be counted on to persecute LGBT+ people.

Do we really want kids in Russia to have Parent No. 1 and Parent No. 2? Have we lost our minds? Do we really want our kids to have it drilled into their heads that there are more genders than sexes? Do we really want our schools to hammer perversions into their heads that lead to degradation and extinction?

So went one of Vladimir Putin’s numerous digressions during his speech at the signing ceremony for the treaties on Russia annexing four partially-occupied Ukrainian territories last month.

In recent years, the Russian president’s rhetoric surrounding LGBT people has gotten crueler and more intense. In 2014, for example, after signing the law banning “gay propaganda” among minors in Russia, Putin pointed out that “non-traditional relationships” themselves were still legal in Russia, denying accusations from human rights groups that the new law was discriminatory. On the other hand, in the same speech, he went on to name “homosexualism” and “pedophilia” as part of the same list, implying a similarity or connection between them. Even earlier, in 2013, he said that “in Euro-Atlantic countries, moral principles and traditional identity are being denied. [Those countries] are implementing policies that put multi-children families on the same level as same-sex partnership, and faith in God on the same level as faith in Satan.”

In addition to maligning LGBT+ people, Putin has told bogus stories about how, in Western countries, “there’s serious talk of registering parties that aim to promote pedophilia.” The party he was likely referring to was created in the Netherlands in 2006 and only had three members. It disbanded in 2010 after widespread public outrage.

Nonetheless, while Putin used to at least pretend that LGBT+ people have the same rights in Russia as everybody else (apart from the “propaganda” law), he now speaks about them as a force to be fought against. Moreover, in his annexation speech, Putin effectively said that one of the goals of Russia’s Ukraine invasion is to prevent the normalization in Russia of all sexualities not sanctioned by the state.

Meanwhile, for Putin and his propagandists, the idea that there are more than two genders has gone from a “perversion” to an “existential threat to the country and its people.” In Russian state discourse, homosexuality has rapidly became as inherent a characteristic of Russia’s enemies as their “commitment to Nazi or fascist ideas." On October 1, for example, pro-Kremlin film actor and Russian State Duma deputy Dmitry Pevtsov claimed Russian troops are fighting for “families to consist of a mom, a dad, and children — not some guy, some other guy, and some other who-knows-what.” And on a Russian talk show in May, he said that “militant faggots have become the main defenders of Ukrainian values.”

The Russian authorities’ rhetoric surrounding gender and sexuality bears a remarkable resemblance to that of numerous other totalitarian, authoritarian, and dictatorial regimes. To gain insight into why this form of intolerance consistently plays an integral role in how dictators maintain power, Meduza turned to history.

The Nazis simultaneously despised and feared LGBT people

The idea of a government-recognized union between one man and one woman as the only permissible kind of romantic relationship is one of the fundamental principles of most fascist regimes. What's more, both members of the relationship must understand their gender in a way that “matches” their sex characteristics; most fascist governments have considered cross-dressing and being transgender just as “deviant” as sex between two men, for example. It’s no accident that in Vichy France, the state motto was changed from Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité (Freedom, Equality, Brotherhood) to Travail, Famille, Patrie (Work, Family, Homeland).

In the Third Reich, LGBT+ people faced mass persecution and were declared a threat to the welfare of the state and of the people. In the minds of Nazi propagandists, gay people were the antithesis of everything Aryan patriots were supposed to embody: asceticism, masculinity, and a willingness to forego pleasure and entertainment to devote oneself to the homeland and the Führer.

Sexual “perversion” in Hitler’s Germany was seen as a remnant of the decadence and hedonism of the Weimar Republic. The Nazis sought to cut all ties with their predecessor state and tightened legislation criminalizing sexual relations between men. Beginning in 1933, when the National Socialist Party came to power and Hitler’s dictatorship was established, prosecution for homosexuality no longer required even physical evidence — it was enough to bring a witness statement from a “law-abiding citizen” who claimed to have seen a suspect look too intensely at another man.

Like in many dictatorships, the image of LGBT+ people that the Nazis pushed was based on two contradictory premises. The first was that LGBT+ people were weak, pathetic, sick people who didn’t deserve to be a part of society. The second was that homosexuality was passed down like a deadly virus and could destroy German society from within if the proper measures weren’t taken to defeat it.

Thus, on one hand, LGBT people were cast as subhumans who deserved contempt, while on the other hand, they were accused of being some of the most dangerous and insidious enemies of the state. The propaganda failed to explain how a group so weak could simultaneously be so powerful.

“In nazi propaganda, homosexuals were generally portrayed as soft, cowardly, cringing, and untrustworthy creatures,” Dutch historian Harry Oosterhuis has written. “[But] in Hitler's and Himmler's view they nonetheless appeared to possess an imperious character and to have at their disposal special intuitions and aptitudes which were withheld from 'normal' men. They were capable of strongly organizing in secret and thereupon making a grab for power.”

In the 12 years the Third Reich existed, according to historians’ estimates, about 100,000 men were arrested for allegedly engaging in “unnatural sexual acts.” Out of the 53,400 men convicted, between 5,000 and 15,000 were sent to concentration camps. The rest were given prison sentences or forced to undergo “treatment.” Persecution against LGBT+ people also got worse as time went on: from January 1933 to June 1935, about 4,000 men were charged for “unnatural sexual acts,” while from June 1935 to June 1938, the number rose to at least 40,000.

Communist regimes were no friendlier

In 1934, an openly gay Scottish journalist and communist named Harry Whyte wrote an open letter to Joseph Stalin. He wanted to explain to the Soviet leader why, in his view, “a homosexual [can be] considered someone worthy of membership in the Communist Party.” At the time, Whyte had been living in the USSR for several years, working as a writer for the English-language Soviet propaganda outlet the Moscow Daily News. Quoting letters written by Marx and Engels, as well as Stalin's own speeches, Whyte criticized the way gay men were treated under capitalism and fascism. He said that even when he had visited Soviet psychiatrists and asked them to “cure” him, they had admitted this might be impossible. He went on to liken the fight for gay rights to the struggle for women's rights.

Whyte expected Stalin to be receptive to his arguments — and to take a kinder view of gay men than that of the British authorities. Instead, the dictator’s response was brief and hostile: “An idiot and a degenerate.”

Shortly after, Harry Whyte left the Soviet Union and was kicked out of the Communist party — but not before Maxim Gorky published a response to his letter in the Soviet newspaper Pravda. “In a country where the proletariat manages courageously and successfully,” Gorky wrote, “homosexuality, which corrupts young people, is recognized as socially criminal and is punished.”

Despite universal equality officially serving as one of the principal ideals of communist and socialist regimes, LGBT people in the Soviet Union found themselves in similar circumstances to those of queer people in fascist dictatorships. The decade that followed the relatively free 1920s was marked by the passage of legislation even more reactionary and repressive than that of the Russian Empire. Like the Nazis, Soviet leaders viewed LGBT+ people with both contempt and fear. In official discourse, gay people were depicted as untrustworthy figures predisposed to deception and betrayal.

The year before Whyte’s letter, the USSR’s Central Executive Committee criminalized “sodomy," making voluntary sex between two men punishable by up to five years in prison.

However, unlike in fascist regimes, where persecution against gay and trans people took place primarily among the general population, "sodomy" allegations in the Soviet Union were frequently used as a pretext for political purges. Facing a “sodomy” charge under Stalin's government was tantamount to being accused of treason.

Over the next 60 years, about 60,000 people were convicted of “sodomy.” Having these charges on one’s record often made it impossible to find work or enroll in university.

Fidel Castro’s Cuba was another communist state in which LGBT+ people faced brutal repressions. For decades after Castro's rise to power in 1959, LGBT+ people were sent to labor camps and forced to publicly renounce their “criminal predilections.” Police arrested men whose behavior they deemed “feminine” or who dressed “like a hippy.” To extract confessions from gay men, investigators would wrap them in barbed wire or bury them up to their neck and deprive them of food and water.

Castro normalized and encouraged homophobia among the public as well. Like current Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov, the Cuban dictator held that “there are no homosexuals in this country.”

The masculinity cult

Nina Khrushcheva, a professor of international affairs at The New School and the granddaughter of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, has attributed authoritarian leaders’ consistent persecution of LGBT+ people to their constant need to emphasize their own strength. The image of a man as the embodiment of masculinity, she writes, is connected in these leaders’ minds with the “natural order of things,” the violation of which poses an immediate threat to their continued power. For dictators and their devotees, queer people provoke not just disgust and confusion but also fear, because they represent an “alternative” order.

Under totalitarianism, homophobic discourse is usually predicated on the idea that if same-sex relationships or non-binary gender identities are normalized, there will be no place for “normal” people in the “new” world. Despite the fact that it’s LGBT+ people who have consistently faced persecution under fascist and communist regimes, dictators promote the idea that queer people are the ones who pose a danger to others. As Khrushcheva wrote in a 2021 column:

These leaders' reliance on “hegemonic masculinity” – the idea that men should be strong, tough, and dominant – to bolster their position should not be surprising. Authoritarian states are fundamentally weak, and dictators are fundamentally insecure. So, they constantly attempt to project strength.

But in today's fast-changing world, ordinary people are feeling insecure, too – especially those who think their traditionally “dominant” positions are being eroded. That makes them eager to embrace strongmen who promise a return to the order and predictability of a more socially rigid past. In other words, people are afraid of change, and think they need macho leaders and patriarchal rules to protect them.

The first order of business for authoritarian leaders seeking to scapegoat queer people is to convince the population that minority sexualities are dangerous. To that end, they usually claim that there’s a correlation between the sexuality or gender identity they disapprove of and some imagined negative trait. For example, authorities might claim that LGBT+ people are incapable of engaging in patriotism or living in society without imposing their “deviant” predilections on “normal” people.

To stir up homophobic sentiment among the public, propagandists try to convince the heterosexual and cisgender majority that LGBT+ people’s worldviews and psyches make them something akin to invaders from another planet. This is because it’s much easier for people to hate “aliens” than to hate people who have everything in common with the majority except their sexuality.

Leaders in authoritarian and totalitarian regimes frequently claim that LGBT+ people are a threat to demography, depicting homosexuality or nonbinary gender identities as a virus that can be passed from person to person. State propaganda traditionally seeks to scare people by asserting that the “spread” of homosexuality will lead to a decline in birthrates — and ultimately to extinction. But this is a fantasy: nothing remotely close to this has been observed in any democratic country where same-sex relationships are legal and socially acceptable.

One of the world’s most well-known homophobic leaders was Robert Mugabe, Zimbabwe’s prime minister from 1987 to 2017. When trying to justify his repressive policies against LGBT+ people, Mugabe often presented the same arguments Vladimir Putin has begun using in recent years: that gay people are “harmful” and “unnatural,” and that their supporters are either “idiots” or “Satanists.”

In the years since Mugabe’s rule came to an end, Zimbabwe has seen the opening of its first health clinics for gay and bisexual men — a step lauded by the local LGBT+ community as a “historic victory.” In other African dictatorships such as Uganda, however, state-sanctioned homophobia continues to thrive.

After inculcating homophobia among the public, dictators themselves usually shape their own public image around stereotypes of masculinity, contrasting themselves with people who don’t fit into their “traditional” conceptions of manhood. And because citizens’ primary responsibility in authoritarian regimes is to buttress the state, LGBT+ people are stigmatized and demonized for not fitting into the model of the “classic” family and for showing their individuality — something authoritarian governments strive to suppress.

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

"With God's help we will surely win. God is with us. We fight to stay human. Against us there are forces of evil: forces of darkness, satanic forces. And it's not fairytale."

Dmitry Pevtsov, Russian actor.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

they just got drunk on bloody marys 🍅

#tw:bleeding#tw: bullet wound#tw: dead body#aleksey serebryakov#dmitry pevtsov#бандитский петербург#bandit petersburg#у2k#the sushi years

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

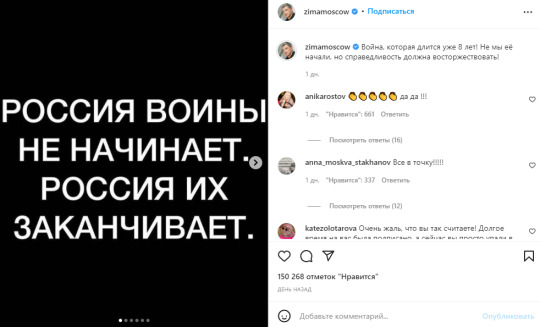

Another "peace guide" Kurban Omarov approves of Putin's actions in Ukraine

Another “peace guide” Kurban Omarov approves of Putin’s actions in Ukraine

Ukrainians should know these “heroes” by sight…

Kurban Omarov supports Putin’s war / Photo: Instagram Kurban Omarov

Russian stars show their true essence in full. In addition to Nikolai Baskov, Dmitry Pevtsov, Tina Kandelaki and some others, Kurban Omarov, the ex-husband of Ksenia Borodina, supported Putin’s war in Ukraine.

On his Instagram page, he posted the same message as the Basques,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

LAVRA: LA DEFENSA DE BOYAKOV FRENTE A LOS LIBERALES

Por Sofía Metelkina

Traducción de Juan Gabriel Caro Rivera

“Me parece, cada vez más, que no existe el tiempo. Todo en el mundo existe de forma atemporal, de lo contrario, ¿cómo podríamos conocer el futuro si no existieran los precedentes?”

Hoy día el teatro se está convirtiendo en un escenario de guerra por las mentes, los corazones y las almas de las personas. Lo que vemos en los escenarios de teatro, fuera de algunas de las obras clásicas, es un enfrentamiento bastante polarizando entre dos corrientes diferentes: la lucha entre la fragmentación posmoderna que es desafío por los conservadores. La obra de Eduard Boyakov y Sergei Glazkov, “Lavra” (1), es precisamente parte de este desafío, especialmente cuando en vez de representar hipsters urbanos que han perdido por completo el sentido de la vida o una serie de pasiones vulgares, ellos hacen aparecer en el escenario a monjes severos y a médicos ascéticos que afirman la victoria de la vida sobre la muerte.

Toda la obra crea el sentimiento de estar realmente frente a la Edad Media rusa. Inciensos reales impregnan con su aroma la sala, con verdadera música étnica que va desde suaves melodías rusas hasta penetrantes melodías orientales o un lobo de verdad que desgarra a un bandido sobre el escenario.

Después de "Lavra" ya no te sientes en medio de la fragmentación y la pérdida, como sucede con muchas de las producciones contemporáneas, sino que, al contrario, sientes la plenitud, la sensación de luz y te das cuenta de cómo participa todo ello en el cielo y la tierra.

Se trata de una interpretación que cuenta la vida de cómo se formó un santo: desde el pequeño niño Arseny hasta el viejo Lavra. No tienen miedo de mostrar en el escenario como este santo también es una persona que vive su infancia, su juventud, su primer amor, su renuncia a los bienes terrenales, sus peligrosos viajes... Todo contrasta en Lavra: las vírgenes inocentes y las esposas depravadas, la sutil unidad de las almas y los procesos biológicos que debilitan la carne humana, el ascetismo y las alegrías terrenas, los días frugales y las pandemias mortales. Y en toda esta representación nunca se escapa la sensación de que toda esta diversidad de la vida se encuentra en las manos de Dios y Dios las mantiene vivas.

Parecería que la participación de actores famosos como Dmitry Pevtsov, Leonid Yakubovich y otros, causaría la destrucción del delicado estado de ánimo que requiere una obra tan espiritual. Por supuesto, a todos se les ocurre que esto pasaría por usar a un bigotudo alegre y amable salido del "El campo de los milagros" o un guapo actor de películas y series de televisión populares. Cuando fui a la obra, le tenía mucho miedo a eso: un texto tan espiritual como "Lavra" no podía ser interpretado por artistas famosos.

Pero mi sorpresa no encontró límites cuando Pevtsov logró captar la narrativa de las páginas del libro de Vodolazkin y Yakubovich resultó encarnar tan vivamente a Nikandr que muchos incluso dudaron de si no se trataba realmente de él.

Todo en esta obra, incluso el diseño técnico, es parecido a realizar un viaje a través de las características sobresalientes que identifican a un enorme icono hagiográfico (especialmente de los que representan las escenas de la vida de un santo) (2) en el que, en cada escena, en cada minuto, sucede algo: alguien muere, alguien canta, alguien comparte sus experiencias y las dudas del héroe. Entre los muertos, solo Ustina, la amada del protagonista, no deja ningún "estigma", y espera humildemente el perdón de Dios y - ¿quién sabe? - un posible reencuentro con el alma de su amado.

La simultaneidad, la ausencia del tiempo, es un estado Divino. La descripción hagiográfica y cronológica de Lavra contrasta con los discursos de los personajes principales, que generalmente dejan de creer en el tiempo. Por ejemplo, Ambrogio dice:

“Creo que el tiempo nos fue dado por la misericordia de Dios, para que no nos confundiéramos, porque la conciencia de una persona es incapaz de captar todos los acontecimientos en un solo momento. Estamos atrapados en el tiempo debido a nuestra debilidad.

- Entonces, en tu opinión, ¿el fin del mundo ya ha llegado?

- No lo excluyo. Después de todo, existe la muerte de los individuos, ¿no ese acaso el fin del mundo para cada uno? Después de todo, la historia general es solo una parte de la historia particular”.

El tema de la ausencia del tiempo y la afirmación platónica del ser y la vida recorre como un largo hilo rojo toda la obra. El tema de la espiral que incluye todos estos acontecimientos, que se repite en cada nuevo giro, también es significativo, lo que solo confirma la integridad y la cohesión de todos los elementos que se encuentran en este mundo, es decir, de cada molinero, lobo, kalach y copo de nieve.

Otra idea extremadamente importante, que se enfatiza en la obra, es la respuesta a la pregunta "¿a dónde vamos?" - "¿Kamo acaso ya viene el Señor?" A menudo nos dejamos llevar demasiado por las vanidades terrenales, moviéndonos en nuestra vida únicamente de forma horizontal. Y el significado de este viaje, enfatiza un anciano en una conversación con Arseny, se arruina si no buscamos un sentido vertical.

Para resumir: “Lavra” es un regalo que nos han dado este 2020, que ha sido muy difícil para todas las personas que se encuentran exhaustas de la pandemia, de las restricciones, de la pérdida de confianza en el futuro y la presión psicológica constante. Durante todo el año, Eduard Boyakov sufrió una gran presión proveniente de la comunidad liberal: algunos lo acusaron de estar atado a un conservadurismo excesivo, otros de que debía cambiar de teatro, otros más, por el contrario, de la ausencia de cualquier innovación. Sin embargo, en mi opinión, "Lavra" es la mejor respuesta a esas críticas, para Boyakov fue solo un pretexto. Es una perla que ha nacido en el Teatro de Arte de Moscú este 2020 y solo gracias a un milagro, debido a la coincidencia entre un lugar y un tiempo específicos combinados al control del teatro debido a un líder sensible.

La revolución conservadora no comienza en las calles, sino que madura suavemente en las mentes que anhelan el retornar a esa viva y significativa Tradición.

Notas del Traductor:

1. Se trata de la adaptación al teatro de la novela rusa Lavra (Laurus) de Eugene Vodolazkin, ambientada en los siglos XV y XVI.

2. En ruso, la palabra Lavra también se usa para designar a los iconos religiosos que tienen ciertos colores azules y representan vidas de los santos.

0 notes

Text

Dmitry Pevtsov Bio, Height, Wiki, Age, Wife, Birthday, Parents & Net Worth

Dmitry Pevtsov Bio, Height, Wiki, Age, Wife, Birthday, Parents & Net Worth

Full Name Dmitry Pevtsov Nick Name Dmitry Age (As of 2019) 56 years old Date of Birth (DOB), Birthday July 8, 1963 Birth Place/Hometown Moscow, RSFSR, USSR Nationality Russian

Gender Male Occupation Actor Ethnicity White Caucasian Religion Not Known Star Sign (Zodiac Sign) Cancer Net Worth & SalaryNet Worth $30 Million Salary $300K per month/episode/movie Income…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

In late November, at a meeting with “soldiers’ mothers,” Vladimir Putin told a woman whose son had purportedly died in Ukraine that “we all leave this world sooner or later,” and that her son “didn’t leave this life in vain” because he “accomplished his mission” rather than “dying from vodka or something.”

Russian propagandists have increasingly voiced ideas like this one in recent months. In early January, for example, TV host Vladimir Sovolyov said on the air that Russians shouldn’t fear death because “we’re going to end up in heaven,” while actor Dmitry Pevtsov said in December that Russians know how to “love, befriend, and die” like nobody else. The trend has prompted some Russian sociologists to start using the term “death propaganda.”

Historian and sociologist Dina Khapaeva spoke to the independent Russian outlet Verstka about the “joy of death” as an integral part of Kremlin propaganda, and the logical extension of Russia’s state ideology. Meduza has summarized the interview in English.

In 1994, a Russian Orthodox bishop named Ioann Snychov published a book called “The Autocracy of the Spirit.” In it, he argued that terror is the best way to govern the Russian people, using Ivan the Terrible as an example: the famously brutal 16th-century tsar, in Snychov’s telling, was a “naturally soft and gentle” ruler who suffered greatly when he had to dole out punishment. The sect Snychov founded advocates for the canonization of all of Russia’s leaders.

Snychov’s ideas were embraced by other extreme figures like Eurasianist philosopher Alexander Dugin, who has written, among other things, that the task of the Russian people is to bring about a “purifying apocalypse.”

According to historian and sociologist Dina Khapaeva, these concepts and others like them have helped fill a void in Russia over the last few decades: the ideological one left in the wake of the Cold War and the chaotic 1990s.

“When Putin came to power, he needed some kind of ideology to rely on,” Khapaeva told the outlet Verstka. “‘Westernism,’ with its human rights and valuing of every life, wouldn’t work. The ideas of alternation of power and political competition, so important for Western ideologies, ran counter to the president’s aims. Communism wouldn’t work either, since the communists were his main political domestic opponents. Then radical nationalists and Orthodox extremists came to his aid. For Putin, they were understandable and organic with their anti-Western and autocratic ideas.”

In Khapaeva’s view, it doesn’t matter whether Putin has actually read the works of Russia’s far-right thinkers or whether he’s receiving them second-hand. The net effect is clear: “Putin and the Kremlin’s ideologues are systematically using [these ideas] and passing them off as their own.”

And the culmination of years of Russia’s top leaders giving these “radical nationalists” their attention, according to Khapaeva, has been an official rhetoric that holds dying for the country as an unmitigated good.

“Instead of a meaningless, hopeless, impoverished life, Russians are being offered a chance to die ‘for the Motherland.’ [By that measure], what matters most is that [the country’s] enemies be destroyed. And the fact that this requires people to die in the process isn’t so important,” she said.

While this messaging has undeniably come in handy for Putin since he launched his full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Khapaeva said, his promotion of the idea that Russians should embrace martyrdom is nothing new.

“The idea of a ‘death cult’ and a ‘purifying apocalypse’ has long been deeply integrated in the Putinist discourse. You’ll even find it in his speeches from the 2010s: ‘We [Russians] will go to heaven, while they’ll just croak,’ and ‘What good is a world without Russia?’” she said.

According to Khapaeva, Russia’s politics of historical memory have developed along two main lines under Putin: “re-Stalinization” and “neo-medievalism.” “You can see this clearly in the way the memories of Ivan the Terrible and Stalin are perpetuated,” she said. “Numerous films that show these figures in a positive light have been made with state money.”

But at the same time, Khapaeva told Verstka, the rehabilitation of these former Russian rulers isn’t a sign that Putin wants to return to a past era. On the contrary, she said, “the glorification of Medieval Russia and Stalinism are tools for promoting anti-democratic values common to both Putin and those dark periods of Russian history.”

And these tools have worked. “Just look at the scale of the anti-war protests,” said Khapaeva. “Throughout the entire country, only a few thousand people went out to protest, and they were easy to suppress. The protests in the U.S. after the start of the war in Iraq were several times larger. And that’s no surprise: in totalitarian societies, which I believe Russia has been since 2014, people value their own lives much less than in democratic ones. What hope for the future can a person have in a society that denies the value of human individuality?”

Once a society has reached that point, Khapaeva said, a war like the current one in Ukraine is all but inevitable. To explain why, she cited a book published in 2006 by former Russian State Duma Speaker Mikhail Yuryev called “The Third Empire: Russia as it Ought to Be.” A “utopian” fantasy novel, the book is narrated by a Latin American subject of a new Russian empire who recounts the process by which Moscow took over the globe throughout the first half of the 21st century.

“It begins with the capture of Crimea, then wars against Georgia and Ukraine. And it ends with the conquest of America and Western Europe. In Yuryev’s imagining, Russian civilization brings treasures to the West — for example, potluck-style class-based banquets that are required for everyone in the empire and that end in drunkenness and brawls, ‘though usually without malice,’” she said.

According to Khapaeva, the book’s author had close ties to members of Putin’s inner circle, and likely even Putin personally in the mid-1990s.

“The aggressive militarism that’s enshrined in this book became the basis of Russia’s state ideology at the very start of Putin’s rule. [Namely, the idea that] the country should be feared, and that that’s the source of its greatness. […] When the president refers to a new atomic weapon as a gift for the country, is that not the best possible example of how little he values the lives of his compatriots? The current war is a consequence of this ‘cult of death,’ not its underlying cause.”

Russia isn’t the first country to be “infected” by such a “death cult,” Khapaeva noted: “This cult cost the Germans alone no less than 10 million human lives, [though] it’s not appropriate to compare the current Russian ideology to German national socialism or communism. Both of these ideologies were focused on the future, [while Russia’s] neo-medieval ideology looks to the past.”

On the other hand, she said, even outside of Russia, a lack of regard for human life has “turned into a commodity on the entertainment market” in recent decades. “The legacy of the 20th century — the Holocaust, the Gulag — dealt a strong blow to people’s faith in man and humanity,” she said. “As a result, in philosophy, in a number of social movements, and in popular culture, there’s been a rejection of the idea that everything should be done ‘for the sake of humanity.’ What kinds of stories find success in popular culture? Apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic [stories, and stories about characters] who deny the supreme value of human life: mass murderers, cannibals, zombies, vampires.”

But while Western society at large still maintains a clear distinction between the value of human life in popular media, on one hand, and in the “real world” (i.e. in government and legal systems) on the other, Khapaeva said that’s not the case in Russia.

“The uniqueness of the Russian situation is that a mix of ‘Orthodox extremism,’ imperial ideology, and an apocalyptic mood has become part of the official state discourse,” she said.

Because millions of people in Russia have now been fed a steady diet of this rhetoric for a significant portion of their lives, according to Khapaeva, it would be “naive” to think undoing its effects will be easy. In fact, in her view, there’s only one thing capable of bringing lasting change.

“It appears that a military defeat and the terrible, radical consequences it will bring to the country is the only thing capable of sobering Russians and causing them to rethink their place in the world,” she said. “That’s likely the only way to heal them from this imperial virus, from this medieval desire to die for the subjugation of other peoples. And then, probably, Russians will be able to think in a new way about what’s worth living for and what’s worth dying for.”

18 notes

·

View notes