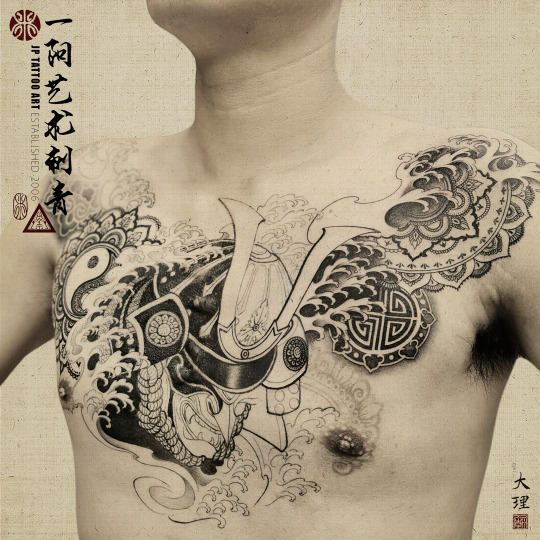

#Samurai and Chinese Mandala

Text

In Progress - Samurai and Chinese Mandala

.

.

.

#Samurai #Samuraitattoo #mandala #mandalatattoo

#blackandgreytattoo #blackngreytattoo #irezumi

#chesttattoo #tattooer #tattooist #tattooartist

#tattooshop #tattoodesign #customtattoo

#tattoooftheday #tattoodaily #asianinkandart

#instattoo #instatattoo #tattoohk #hktattoo

#hongkongtattoo #侍 #曼荼羅 #曼陀羅 #紋身 #香港紋身

#刺青 #ダトゥー #만다라타투

#Samurai and Chinese Mandala#Samurai#Samuraitattoo#mandala#mandalatattoo#blackandgreytattoo#blackngreytattoo#irezumi#chesttattoo#tattooer#tattooist#tattooartist#tattooshop#tattoodesign#customtattoo#tattoooftheday#tattoodaily#asianinkandart#instattoo#instatattoo#tattoohk#hktattoo#hongkongtattoo#侍#曼荼羅#曼陀羅#紋身#香港紋身#刺青#ダトゥー

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

5. Naomi Kawanishi Reis & Alex Paik

Naomi Reis and Alex Paik discuss childhood survival mechanisms manifesting in their work, in-between-ness, their labor-intensive practices, and Naomi’s recent body of work which was shown at Transmitter (Brooklyn, NY).

Alex Paik (AP):

You’ve been thinking about camouflage in an ongoing series of your work, and it strikes me that this idea of hiding and/or being invisible is central to your work. Now that I think of it, even your work in grad school, which was about these sort of hybrid utopic (or dystopic) architectures had this silence in them. There were no figures and no real record of anyone having lived or living in those imagined spaces, like they were erased or hidden. When you started talking about camouflage in recent years it really was an a-ha moment for me in understanding your work. I’d love to hear your thoughts more on the invisibility of Asians in general in the art world and the ways in which that feeling might be a part of your work.

Naomi Kawanishi Reis (NR):

Camouflage was something I started using about eight years ago, in a series called Borrowed Landscape. The series was based on photographs I took in the tropical biomes of conservatory gardens, a take on landscape painting where the “nature” being depicted was a highly curated by-product of Western colonialism. Plants that were highly useful/exploitable/profitable/exotic and beautiful, collected in a place that existed outside of time, secreted away from the effects of weather and death. I translated those photographs onto printed wallpaper, upon which was placed a framed mixed-media painting that replicated a portion of the wallpaper behind it.

Naomi Reis, Borrowed Landscape II (Tropics of Africa, Asia and the Amazon via Brooklyn), 2013. Digital print on vinyl and handcut washi and mylar cutouts in maple frame, 13.5 x 14 feet. Installation view at Susan Inglett Gallery, New York, NY in “American Beauty,” curated by William Villalongo. Photograph by Jason Mandella.

NR:

I was thinking about how landscape has been used in image-making throughout history to depict idealized places—like Pure Land paradise in Buddhist mandalas, the Taoist spiritualism of Chinese or Japanese landscape paintings, and the glorification of nature found in Romantic landscape paintings.

The title “Borrowed Landscape” comes from a 7th-century Chinese garden design concept (shakkei=借景, a technique of “borrowing” the view of a distant scenic element, like a mountain or lake, into the design of the garden), which felt like a fitting title for where we find ourselves today in relation to landscape. Living on borrowed time, on stolen land: ignoring the reality of our responsibilities to the land, the indigenous people it was stolen from, and the debt owed to stolen Black bodies and labor in service of white supremacy. The handmade framed painting, I suppose, is a stand-in for us as immigrant settlers on this land here in America; we’ve camouflaged ourselves into our surroundings to fit in, to survive. The land we are attempting to fit into, is itself “borrowed” (aka stolen).

These choices weren’t made consciously when I started the series; it’s only now eight years in that I’m beginning to understand the why, and finding the words to explain it. As a diasporic, racialized person both in America as well as in Japan, I’ve needed to navigate complex social and racial situations. My father’s side of the family is white and doesn’t speak Japanese, so as a kid I knew that in order to survive and be “liked” by that side, or maybe even just to be understood, I needed to downplay my otherness and be as “normal,” aka white English-speaking, to them as possible. Conversely, my mom’s side of the family is Japanese and doesn’t speak English, so to them I needed to be as Japanese as possible. Of course as a kid you get a pass to a degree and are loved anyways, but I do remember this feeling of anxiousness, that my survival and ability to be loved and cared for depended on this ability to code-switch.

Being the oldest in a family of three siblings, and because my experience was so different from my parents’ monocultural upbringing (Japanese in rural Japan for my mom, white American in suburban NJ for my dad), code-switching was an essential survival tool. Kids instinctively figure out how to protect themselves at a very young age, even before they learn how to express themselves verbally. Immigrants adapt similar survival tactics, the art of blending in. Though “blending in” is a way to survive, it also is an act of self erasure. How to survive, while not annihilating yourself in the process? You camouflage.

The reason for the absence of figures in my work probably comes from feeling absent from my own narrative, feeling a bit unmoored from belonging to any one culture. I didn't see myself being reflected in the context of mainstream Japan or in America or anywhere except for maybe sci-fi or fantasy. Growing up I often felt like a ghost, like I didn’t exist in the real world. While I had learned how to integrate enough to survive, as I was getting up to speed with my fluency and literacy in English and Japanese while going back and forth between the U.S. and Japan, I often felt I was on the sidelines watching other people live their lives and not feeling comfortable enough to fully participate. When my family moved from Ithaca, NY to Kyoto in the ’80s when I was 9 for my dad’s teaching job at a Japanese university, I was often called 外人=outside person by strangers on the street. As a sensitive kid, I internalized that othering a lot.

The architectural work I was making in grad school was a kind of perverse take on modernist architecture, multiplying and ornamenting the hell out of the piloti and flat roofs of the International Style, a style that aimed to strip all ornamentation and color to become a “pure” architecture. The absence of figures became like the blank-slate of a dollhouse, a place I could imagine roaming around in.

Naomi Reis, Vertical Garden (weeds), 2007. Hand-cut ink and acrylic drawings on mylar, 53 x 45 inches. Photograph by Etienne Frossard.

AP:

I can relate so much to this, being the first-born child of immigrants. It is interesting to think about these survival mechanisms in relationship to our work. I have been reflecting recently on my site-responsive installations, how they adapt and change depending on the size, time, and location of the piece, and how this is a metaphor for how one can rearrange the parts of the self depending on the social context. Code-switching would be one aspect of this. One of the feelings I remember most from childhood, perhaps because of moving a lot as a kid, perhaps because of being Korean-American and not quite feeling Korean or American, is that of constantly feeling like I need to assess the room and adapt to it. So while you are drawn to the idea of hiding/camouflage in your work, I am drawn to the idea of constantly adapting and rearranging the different components of the self. Two sides of the same coin I guess.

NR:

Ah that’s interesting. Your strategy is to go on defense, which maybe is connected to your training in martial arts, and your attraction to building communities like TSA, whereas mine is an introvert’s tendency to self-isolate, to find a way to take up space while remaining hidden—yang vs yin.

To return to your question about why work made by Asian artists seems hidden behind some kind of invisibility cloak: that’s a reflection of where we’re at culturally in America generally. Asian stories remain largely unknown; they are insufficiently featured in mainstream media and curricula, so Asians have largely remained the consummate “other” whose experience is hidden and therefore not relatable to many Americans on a heart, gut level. White America tends to project an expectation of whiteness onto others, so when your actions or motives aren't matched in a way that’s relatable to a white audience, you confuse expectations and can be seen as an unknowable other that’s doing things wrong or badly. When you are seen as an other, it makes you vulnerable to either being too too visible—a target that needs to be taken down for taking up space that we don’t deserve, as we’ve seen play out recently in the attacks against Asians in America—or not relatable/relevant and therefore invisible, an easy target for cultural appropriation or the butt of a joke.

American culture likes extremes. Black or white, good or bad, democrat or republican, man or woman. Personally I feel most comfortable in the in-between, where everything is still in the process of forming, and reforming. Queer spaces. Because they encompass, in theory, all shades of ambiguity. Going back to the idea of binary space, people tend to be attracted to things that either remind them of themselves, or on the opposite extreme, that provide a projected escape into the exotic “other.” In movies you often see Asian-ness as an alienating backdrop to heighten tension for the central white characters you are meant to identify with: Asian bodies as embodiment of a dystopian future (both Bladerunner movies, Artificial Intelligence, Minority Report); as nonsensical foreigners in their own country (Lost in Translation); as hapless natives who need saving (Last Samurai).

AP:

What aspects of your work do you see as talking about the in-between?

NR:

My work is maybe less aiming to talk “about” the in-between, and more just wanting to “be” in the in-between. The process of making “it,” whatever “it” ends up being—is itself what creates the space and time to occupy an in-between—a wordless space that exists for the interval while engaged in the act of making. The 間 space: a Japanese word that refers to the in-between, both spatially and temporally. This is the space in which all artists work, falling into that pocket of space-time where things are in flux.

It’s a way to give yourself permission to inhabit space—”to be” without having to translate that state of being into a binary (English/not-English; American/not American; male/female; young/old). Even now, writing this out, and to you, Alex, I am inhabiting my English-speaking self who is translating the self into a form that is legible to an English-speaker. Talking to my mom, I am inhabiting my Japanese-speaking self and all the historical cultural gendered background that goes into being that particular self. Talking to my siblings or bilingual friends, fluidly switching between English and Japanese, is a way to occupy the in-between for that interval of time, then returning to the binary world of everyday life. Didactically speaking, I suppose my work is “in-between'' in that it is kind of painting, kind of drawing, kind of collage, kind of abstract, kind of representational, kind of naive, kind of sophisticated. Kind of American? Kind of Japanese? Kind of good? Kind of bad? A physical thing that takes up space, and that space can encompass all the ambiguous in-between mushy-ness.

I didn’t feel able to pursue being an artist until I was in my mid-20s. I had a lot of shame about not being good enough, of not deserving to do it. Still do. I hadn’t gone to art school, and wasn’t encouraged to be a creative person by society or parentally. It was something I wasn’t open about, I drew and painted alone in the privacy of my room. So by the time I was in my mid-20s and realized working a normal job was killing me (I was a human resources representative at the NY office of a Japanese printing company), and that I really had to give artmaking a go, I didn’t know what I was doing.

At the time, I was fascinated by architecture. The idea that you could take a philosophy, a belief system, and turn it into a permanent structure that’s inhabitable, that can last for centuries. Maybe that fascination came from growing up in Kyoto around buildings that had been around for 1,200+ years. So when I started in the MFA program at Penn Design and was making architectural sketches in 3D-modeling programs, it came from a feeling of: if I can imagine an inhabitable place within which I can exist, I can open up a non-binary space to work within. Anytime I can overcome my inner demons or lack of talent or confidence or imposter syndrome, etc. long enough to crack open some space and just make the work, that’s a victory. Generally, in the year ahead I want to make work that comes from a place of joy. Worrying less about how my work fits in, and just focussing on creating the conditions within which I can feel more exuberant, and free. When you allow those conditions for yourself, I think you can do the same for others.

AP:

Another exciting thing about your work is how it is busting out of the rectangle more! Obviously I am all about that :) Can you talk more about how that happened and how you are thinking about it?

NR:

Ha! I think it comes from a desire to to be more joyful, bust out of the seams, take up more space. Allow for messiness, draw outside the lines. I want to make more space for weirdness. It must come from a desire to push against the narrowly-defined rules for acceptable female behavior that I grew up with in Japan, and the kind of bubbling rage I felt for the myriad of ways women and their bodies are policed, undermined, silenced, and funneled into serving a capitalist nationalist patriarchal system, where the myth of ethnic/racial purity is perpetuated through the education system. Harm and denial begets harm and denial, and I wanted to get out and find a different way.

AP:

I love the idea of the work taking up more space than it is given. It goes back to the idea you talked about earlier of becoming an artist to create a space that didn’t exist for you previously, and of pushing against/beyond essentialist and reductive readings of art based on identity.

NR:

How about you, Alex?

I’ve always sensed there’s a reticence in you to talk more directly about what your work is about, to not allow yourself that level of vulnerability. For example, sometimes you refer to your time in the studio as being boring repetitive labor, and I was wondering if there might be a connection there between the type of labor involved with the work your parent’s did as owners of a dry-cleaning business. Can aspects of your work be seen as a kind of penance, or perhaps tribute, to the kind of labor that was available to Asian immigrants when you were growing up? You are the artist, so you get to dictate the terms. Why limit yourself to a mode of making that you say is repetitive and boring? Maybe there’s something important there in that repetition and boredom that you are committed to, and I want to know what it is, and why. What do you want and dream about for your work?

AP:

I am becoming more comfortable with it recently. While I hesitate to draw a direct connection between the type of menial labor that my parents did and the type of work I am making, I do think that my upbringing shaped my personality and interests for sure. Seeing them work so hard and feeling the pressures of being the first-born (pressures stemming from my parents, from Korean culture, my own guilt in wanting to honor their work, my own internalized capitalism) definitely has instilled an appreciation for labor. I have always been drawn to things that require discipline and repetition—classical music, martial arts, cutting strips of paper over and over again.

I was thinking about my work through a very narrow lens for a long time, trying to keep it in the lane and lineage of the art history I was taught. Once I opened up my thinking about my work as an extension of the totality of my life experience and interests including but not limited to my Korean-American identity, it allowed me to see things in my work and myself that I hadn’t been willing to explore. That being said, I am hesitant to make my work only or primarily about my racial identity. I feel a lot of external and internal pressure that I am supposed to be making work about my racial identity.

Your work is also very labor intensive. Can you talk about how you think about that in your studio practice?

NR:

I think it goes back to the in-between space, to the relief I get when I release into the labor of work; there I am temporarily free from the anxiety of not-belonging. So the more labor intensive it is, the more I get to be free. In the past several years I also have been spending more time trying to heal: learning how to meditate, and in various forms of therapy like EMDR and somatic experiencing. A healer I’ve worked with who specializes in somatic experiencing mentioned that a lot of people who’ve experienced trauma engage in repetitive labor, that there is release and relief, a self-soothing, in that labor. It makes me nervous to think that the labor-intensive nature of my work can be explained away as a form of self-medication, but on some level the creative impulse always comes from some kind of unnameable necessity.

AP:

It’s such a gift to been friends with you for over 15 years and also to have seen your work grow for that long. It’s exciting to see a lot of these ideas coming together in your most recent body of work that you showed at Transmitter. Can you tell me more about this recent series?

Naomi Reis, 71229 (9:17), 2021. Acrylic on washi paper and mylar cutouts, 93H x 55W inches. Photograph by Carl Gunhouse

NR:

In my most recent work, I worked off of photographs my mom has been sharing of her flower arrangements on our family group chat, which is the primary way we all keep in touch (my mom, brother, and his family are in Japan, and me and my sister and her family are in NY). My siblings post photos of their young kids, I post photos of my work, and my mom posts photos of her cooking and flower arrangements. Photos of the domestic realm. This new series is an attempt to bridge the ruptures that distance can bring: geographical, generational, and cultural/philosophical. There’s definitely a lot of tension in our different ways of thinking about gender roles, so the thought was to translate those gaps of expectation into a form that heals and transforms, through the labor and care that goes into the process of making. Maybe this work is my version of a quilt or weaving piece—a labor-intensive process that is meditative, with all the analogies and histories of weaving, knitting together, mending—embedded within.

Naomi Reis, 111119 (90˚W), 2021. Acrylic on washi paper and mylar cutouts, 48H x 37W inches. Photograph by Paul Takeuchi

Born in Shiga, Japan, Naomi Kawanishi Reis makes mixed-media paintings and wall pieces that focus on idealized spaces such as utopian architecture, conservatory gardens, and still life. She has had solo exhibitions at Youkobo Art Space, (Tokyo) and Mixed Greens, NY; she has also exhibited at Brooklyn Academy of Music and Wave Hill. In 2018 she received a Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters & Sculptors Grant, and in 2015 was a NYFA Finalist in Painting. Residencies that have supported her work include Yaddo and Robert Blackburn Printmaking Workshop. Reis also is a Japanese to English translator; recent publications include the chef's monograph “monk: Light and Shadow along the Philosopher’s Path” (Phaidon Press, 2021). She received an MFA from the University of Pennsylvania, and a BA in Transcultural Identity from Hamilton College.

www.naomireis.com

@naomikawanishireis

Alex Paik is an artist living and working in Los Angeles. His modular, paper-based wall installations explore perception, interdependence, and improvisation within structure while engaging with the complexities of social dynamics. He has exhibited in the U.S. and internationally, with notable solo projects at Praxis New York, Art on Paper 2016, and Gallery Joe. His work has also been featured in group exhibitions at BravinLee Projects, Lesley Heller Workspace, and MONO Practice, among others.

Paik is Founder and Director of Tiger Strikes Asteroid, a non-profit network of artist-run spaces and serves on the Advisory Board at Trestle Gallery, where he formerly worked as Gallery Director.

www.alexpaik.com

@alexpaik

0 notes

Text

Styles

TRADITIONAL TATTOO

Traditional tattoos are characterised by thick black or blue outlines and solid bright colors (red, yellow, green, blue). The result is a bold, big design that can sometimes look "rude" if compared with more advanced tattoo styles. Traditional tattoo style was done by sailors, inmates and people without a tattoo artist diploma, and with a primitive tattoo equipment. Today we have materials and tools, but the old school style is inspired by this traditional tattoos so it "traces" the same features.

http://www.rebelcircus.com/blog/tattoo-styles-guide-old-school/

BLACK WORK

All the variants of Black are here: bold or fine line, dot work and whip shade allow talented artists to create mystical patterns with supernatural effects.

The designs asked for are mostly tribal or neo-tribal inspired however the possibilities are endless. The Blackwork tattoo style is not a new tattoo style even if it seems to benefit from a large media coverage recently. Black is the first color that appears in tattoos and has been used by artist since the creation of tattooing in the ancestral tribes. Blackwork tattoos are much more than a recent trend as it is completely connected to the origin of tattooing.

We are pleased to see that the artist redefined the art of Blackwork tattoos by bringing new ideas with their techniques and skills. Some of them specialize only in this timeless tattoo style and contribute to the evolution of our art. Black is a powerful and symbolic color that looks stunning on any skin type.

Blackwork tattoo allow you to choose from a lot of designs or create your own with an artist here in The Black Hat Tattoo as there is always new ideas coming to the minds of our amazing talented artists.

https://www.theblackhattattoo.com/tattoo/gallery/black-work-tattoo/

DOTWORK

Dotwork tattoos are one of the most intricate styles. Complicated geometric images are created with nothing but dots. The tattoo artist must be very patient and very talented because he has to place every dot in the right place. Many dotwork artists have also abandoned the tattoo machine and are performing handpoked tattoos. Dotwork tattoos are a style on their own, and the shading you get through dots is almost 3D. You can't get that kind of shading with any other method. The dotwork technique is used especially for geometric tattoos, religious and spiritual tattoos.

The dot tattoo is usually done with black ink, or grey ink. Sometimes red is used, but only because red creates a beautiful contrast effect on geometric tattoos. There are some remarkable artists that specialise in the stippling method. We have featured one on Rebel Circus some time ago. Check out Kenji Alucky. He's a Japanese tattoo artist who creates awesome intricate designs and is really talented. We can also mention other tattoo artists like Thomas Hooper and Jondix.

We've mentioned that the stippling method is used for religious tattoos. Tattoos have always had a religious and spiritual connotation in many cultures (especially Asian or in tribes like Maori). A tattoo artist is often also a shaman, a healer. Tattoos have an energy on their own and when you get specific symbols tattooed, you need to know that those symbols can be very powerful. The dots technique is often used for mandala tattoos, and more often than not those tattoos are hand poked. A tattoo gun is not the best tool when it comes to dots. Hand poking requires a lot of patience, but it's the best method for getting all the details right. Some of the recurring subjects for dotwork tattoos are mandalas, symbols like the Hamsa hand, the Eye of God, lace, decorative patterns like filigree, animal portraits (especially wolves, cats, foxes, snakes, butterflies,) animal and human skulls.

Getting a dotwork tattoo usually takes more time than a regular color filled tattoo. If you go to an artist who only uses the hand poking technique, it will take even longer. But the results will be so good that you won't regret it!

http://www.rebelcircus.com/blog/dotwork-tattoos/

WATERCOLOUR

Watercolor tattoos make use of splotches of color without outlines to imitate watercolor paint. This style has exploded in popularity in the past few years! While it is a really interesting and beautiful new style, it is difficult to tell how it will age without the use of strong black outlines.

https://www.theodysseyonline.com/tattoo-style-guide

Blurs, bleeds, splatters, runs, fades & shades – turn your body into a canvas. With watercolor tattoos, the normal rules of tattooing do not apply. While some watercolor tattoos still feature black outlines, the tattoo artist will deliberately bleed color outside of these lines to create a beautiful watercolor effect.

This type of inkwork is modelled on watercolour canvas paintings which have a long tradition in western art and is best exemplified in the mindblowing art of J.M.W. Turner. These tattoos don’t actually use water of course, but rather they reflect the aqua-based paint of such iconic watercolour painters. All the same tools as conventional tattoos are used in the process, but the technique differs quite dramatically in order to achieve this unique effect on the skin.

The idea is for these tattoos to look like a painting, and in this sense they are the logical advancement of tattooing as it comes to be recognised more and more as a legitimate and indeed cutting edge art form. They’re perhaps the truest expression of considering one’s body a canvas.

Watercolour tattoos are centred on a hazy effect as colours bleed into another to mimic the appearance of painterly works. A splatter effect is also an interesting option, as is a running ink effect. These are playful ways of deepening the reference to fine art. These can make the tattoo appear ‘messy’ but is in fact the result of very precise needlework by the tattoo artist.

In terms of subject matter, animals are often depicted. Animals are known for freedom and closeness to nature; they’re often evoked as romantic subjects in art. Fast-moving creatures such as foxes can create especially spellbinding watercolour tattoos. Fans of abstract art are also drawn to watercolour tattoos, as they allow for a huge degree of experimentation and expression. The bright colours of this type of inkwork is additionally a natural fit for someone looking to profess support for LGBT+ causes,

https://www.theinkfactory.ie/welcome-watercolour-tattoos/

MANDALA

Mandala Tattoos are Indian spiritual and ritual symbols which are symbolic of the grandeur of the universe. These designs come in many shapes, circular or floral, a mandala can be made in any shape of your choosing.

These designs are heavily used both in Buddhism and Hinduism and have recently become a very popular work of art globally in the tattoo industry. Many artists pride themselves on their ability to Tattoo these intricate pieces and here at Image & ink our super spiritual artist “Om Nama Shivaya” has great knowledge in the art of mandala tattoos and other spiritual symbolism.

You don’t necessarily have to study the practice of meditation for six years, then sit fasting underneath the Bodhi tree for 7 days in an attempt to reach full enlightenment to have a mandala tattoo. A lot of these designs are beautifully decorative and result in a wonderful tattoo.

The mandala is a Buddhist and Hindu spiritual symbol that represents the universe in a microcosm. The circular shape denotes balance, perfection, eternity and the never-ending cycle of life. For individuals, a mandala can symbolise one’s journey through life and the many elements that make it. A mandala can be executed using simple linework or dotwork, or a mix of both.Sacred geometry has been for a long time a wonderful and beautiful form of tattooing and can be customised in any way, shape or form. A lot of mandalas can be incorporated into a sleeve, starting from the wrist, flowing up the arm. Also very popular to be added to a thigh, back or shoulder.

https://www.theinkfactory.ie/tattooing/tattoos/mandala/

IREZUMI/TRADITIONAL JAPANESE

Asian themed tattoos frequently using Koi fish, cherry blossoms, Buddha, lotus, dragon’s, war dogs, samurai’s or geisha’s. Many of these are used in combination to tell a story as well as create a piece of timeless art. This type of tattoo is usually very detailed. This is basically a tattoo that will cover the whole body. The work is carefully planned out ahead of time before the work on any part of the body begins. This style seems to be more 2 dimensional or flat, almost like print on fabric.

http://www.sinonskin.ca/tattoo-styles.html

Japanese tattoo style is probably one of the most influential styles on modern tattooing and it has a very long history. Tattooing in Japan extends back to the Yayoi period (c. 300 BC–300 AD): tattoos had a spiritual meaning and they also functioned as status symbol. In the Kofun period (300–600 AD) they started to be used as marks for criminals, therefore with a negative connotation. We should also mention the Ainu, the indigenous population of Japan, they used to have tattoos on their arms, mouth and sometimes forehead. They have lived in Japan for thousand of years and they've also been integrated with the more modern civilization; there's no doubt they have somehow influenced the art of Japanese tattooing. Although, what really influenced Japan tattoo style are the "pictures of the floating world" (called ukiyo-e in Japanese) which are essentially wood-block prints. One of the most influential ukiyoe artists was Kuniyoshi, who illustrated the Suikoden. This story featured 108 Chinese corrupt rulers, who were all tattooed: these images of tattooed warriors still have major influence on tattooing today.

This kind of traditional tattoos were associated with the yakuza (Japanese's mafia) for many years. In Japan tattoos are ironically not so common as in the Western world because they're still strongly associated with criminals. Some fitness centers and hot baths still ban customers with tattoos for this very reason. Yakuza's members are some of the few people to have bodysuits in Japan (with bodysuit we refer to having your body covered with tattoos).

So what brought Japanese tattoo style to the Western world? Sailors, who else? Western tattoo artists copied these intricated designs; dragons and koi fish or had them tattooed while in the Navy. The result is that we have a lot of Western tattoo artists working with Japanese traditional tattoo art, which is today very popular.

Japanese Tattoo Style Motifs

Mythological monsters such as dragons, animals like birds, koi fish, tigers and snakes are exceedingly popular. Flowers like cherry blossoms, lotuses and chrysanthemums as well. Characters from traditional folklore and literature, such as the Suikoden (geisha, samurai, criminals) Buddhas and Buddhist deities such as Fudō Myō-ō and Kannon and Shinto kami deities such as tengu are also remarkable. In all Japanese tattoos there is always some kind of background; they look very "full" and 2D, almost like a textile and the backgrounds are clouds, waves and wind bars. Did you know that there are very firm rules about the location of tattoos on the body? For example clouds should be used above the waist (because they represent the sky) and waves below the waist. It is not allowed to tattoo Buddha below the waist because it would be disrespectful. Flowers should also be coordinated with the animal of choice: if you want to get a koi fish swimming upstream you should pair it with maples or chrysanthemums, because the koi fish only swims upstream during the fall.

http://www.rebelcircus.com/blog/japanese-tattoo-style/

TRIBAL

Tribal tattoos have been in vogue for quite a while now (since the early 1990s), and while their popularity is diminishing, they are still going strong.

These are the Advantages of getting a tribal tattoo:

There's a lot of black ink in tribal tattoos, which has the advantage that it holds up well, black tattoo ink doesn't fade as fast as other colors.

Tribal tattoo designs are extremely popular, so as long as you don't want a specific or traditional tribal, you shouldn't have a hard time finding a reputable tattoo artist that can design your custom tattoo.

It's easier to design your own tattoo or at least a mockup of your own tribal than it is with other tattoo designs.

Tribal tattoos have a bold visual appeal: their thick, black curving lines and interlocking patterns lend themselves well to many of the standard tattoo locations, such as the upper arm (in the form of a tribal armband, for example), the back or the lower back.

The tribal styles we see today originate from various old tribes like those from Borneo, the Haida, the Native Americans, the Celtic tribes, the Maori and other Polynesian tribes.

The shapes and motifs of these tribal tattoos are deeply rooted in the tribe's mythology and view of the world. The traditional tattoo artist aims to reflect the social and religious values of the tribe in his tattoo designs. Recurring themes are the rituals of the tribe, the ancestors, the origins of the world and the relationship with the gods.

Modern tribal tattoos are not strongly associated with any particular tribe and are usually stripped of their social meaning. The designs we see in the Western world today are often based on:

Polynesian tattoo designs.

The tattoo designs of the tribes of Borneo, namely the Iban and Kayan (Sarawak) and the Kenyah (Kalimantan).

http://www.freetattoodesigns.org/tribal-tattoos.html

SACRED GEOMETRY

Since dotwork tattoos have been having their peak in popularity, another style has also become very popular: sacred geometry tattoos. Most of the times the two styles go together, geometric tattoos are often performed using the dotwork technique (as are animals, occult symbols and engraving inspired tattoos). With sacred geometry we refer to those shapes and patterns that are found in nature and that are perfect, such as the spiral of the golden section (we're sure you've seen the nautilus shell in many tattoos), and other designs such as the flower of life or the Gordian knot. Most of the times these designs and patterns are perfectly symmetrical, and generally include circle shapes. One of the most common designs are mandalas, generally squares containing a circle and many other geometric shapes, forming a whole with a radial balance. Platonic solids like the dodecahedron and the icosahedron are common as well, as are all the shapes that recall the idea of oneness and connection with the natural world that surrounds us. Sacred geometry tattoos are very spiritual tattoos.

Many people who choose to get sacred geometry tattoos often do it for the meaning of the design, not for the "shallow" beauty. For example, the platonic solids we mentioned above have precise meanings. The cube represents earth, while the tetrahedron symbolizes fire. The octahedron symbolizes air, the dodecahedron spirit or ether and the icosahedron refers to water. Some people believe that positioning these shapes over a particular part of the body will affect their spirituality or health in a positive way. If you think about it, tattoos have always been used as amulets, talismans and for protection. This was even common among sailors back in the 40s and 50s. Ancient cultures believed that tattoos had to be performed by shamans (like Polynesian tribes) and they symbolized their position in the society, while also having magical qualities.

Today, many of these sacred geometries can be found blended with other tattoos, included in other designs just as decorations. Or they can be used as a holistic practice. These symbols are meant to make your energies and vibrations higher, and even if you think that it's a placebo effect, we think that it's worth trying. Today tattooing has developed a lot as art, we have electric machines and we can use very vivid colours and alongside this process, sacred geometry tattoos has also been rediscovered. Pain is almost no longer part of the "ritual" but sacred geometry patterns and designs still hold their fascinating and magical allure to us.

http://www.rebelcircus.com/blog/sacred-geometry-tattoos/

0 notes

Text

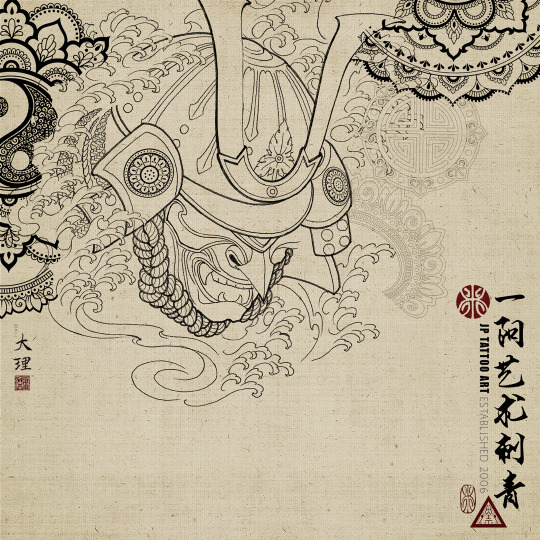

Samurai and Chinese Mandala

.

.

.

#Samurai #Samuraitattoo #mandala #mandalatattoo

#blackandgreytattoo #blackngreytattoo #irezumi

#chesttattoo #tattooer #tattooist #tattooartist

#tattooshop #tattoodesign #customtattoo

#tattoooftheday #tattoodaily #asianinkandart

#instattoo #instatattoo #tattoohk #hktattoo

#hongkongtattoo #侍 #曼荼羅 #曼陀羅 #紋身 #香港紋身

#刺青 #ダトゥー #만다라타투

#Samurai and Chinese Mandala#.#Samurai#Samuraitattoo#mandala#mandalatattoo#blackandgreytattoo#blackngreytattoo#irezumi#chesttattoo#tattooer#tattooist#tattooartist#tattooshop#tattoodesign#customtattoo#tattoooftheday#tattoodaily#asianinkandart#instattoo#instatattoo#tattoohk#hktattoo#hongkongtattoo#侍#曼荼羅#曼陀羅#紋身#香港紋身#刺青

12 notes

·

View notes