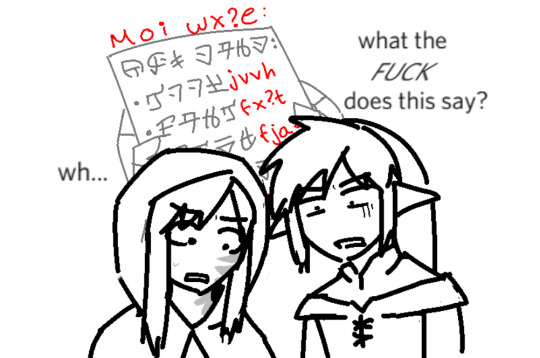

#also it says: for wild: eggs. milk. meat. arrows

Photo

their written hylians might be similar but they’re in NO way interchangeable

#fun fact! botw and albw/tfh share the same alphabet. which shares a lot of symbols with ss's#but theyre like. remixed. so the only word you can have in both at the same time is 'NO'#linked universe#wild linked universe#legend linked universe#lu wild#lu legend#this was funnier in my head but oh well#as always i drew this in class and literally everything is funnier while bored out of my mind#also it says: for wild: eggs. milk. meat. arrows#the hylian writing system fascinates me i have a file where i see how ss's alphabet evolved into botw's#like graphic wise not like. actual reasons#tortilla stop rambling in the tags challenge#i like to think since time most definitely doesnt know how to read he just makes the other links write down the shopping list#so it leads to this kind of thing to happen like 80% of the time#sky's technically not here but... uh#sky linked universe#lu sky#tortilla arts#tortilla posts#linked universe art

721 notes

·

View notes

Note

I've been following you for a really long time and this is the first time I've ever wanted to ask you a question. But why would you go camping alone without any light? That's just a really dumb thing to do...

(in ref to my tags here im pretty sure)

gather round, dear followers, for a series of anecdotes from Hell Camp, the source of my best and worst stories

when i was twelve my school sent all its year nine students class by class to a five-week camp, which will henceforth be called Hell Camp. here is the setup:

a four-hour drive out of the city into the outback, where there is a farm owned by the school for the express purpose of hosting Hell Camp

28 girls and 28 boys, each in their own dorm houses

no phones. no computers, no ipods, no TV. no internet (within our reach). we cooked our own food on fire stoves and wrote letters by hand to our parents and friends

no lollies, no soft drinks or juice, all our eggs and milk came off the farm

wake up at 5:30am every day to go for a 3km run and then chores on the farm, from milking the cows to chopping our firewood

Bible study every night because this was a Christian private school

“why???” u may ask. “why did your school subject tweens to a month of this???” supposedly to build character and teach u life skills but tbh idk how knowing how to crack a bullwhip is supposed to help me in life

but it wasnt just five weeks straight of same ol farm life there were other activities they had us do!! camp-like activities!! for example:

Pre-Survival

three days to prepare us because we were innocent younglings who barely knew how to start a fire

basically a campsite in the middle of fuckass nowhere? we rode horses there while the counselors (the Hell Camp resident teachers, but ones that deadlift 50kgs and kill spiders without batting an eye) drove with our bags and stuff and laughed as we got inevitably lost

have u ever used a dunny u have to empty urself

it is so gross. there is a field marked out explicitly for burying everyone’s shit, and u have to take turns. so gross.

there was a shower which was a metal shed with a bucket of water hung up, which u heated over the fire before u went in and prayed it wasn’t too hot

this was like winter time and we slept in swags on the ground and when we woke up there was frost on our swags

i made an iron horseshoe??? the temptation to touch red hot metal is ridiculous tbh it looks so pretty

someone did touch theirs. it was not me. i heard them yell from across the field where i was helping feed horses.

in the middle of the second night the counselors took us to a giant rock in the middle of the bush where u could see the stars and it was amazing you could see the milky way and everything… but the thing was we had to spend the previous 20 minutes in the dark to get our eyes used to it so they had us hold onto each other’s sleeves and walk blindly into this rugged, rock-covered trail through pitch blackness, praying no one in front is going the wrong way

and then. the counselors played a trick on us by getting one of the kids to stay back in the forest and waited to see how long we’d notice. we didn’t notice until it was time to go back im so sorry Kimmy

Survival

ok this the real shit you went with the same group you were with in pre-survival and the counselors drove you out into the depths of the outback and dropped you and your group off with some tools, food, and tarpauline

and then u just lived out there for three days.

we couldn’t start a fire our first night because it’d been raining before??? our dinner was supposed to be rice, potatoes and carrots, and the carrots were the only edible thing bc u cant eat raw rice and raw potatoes.. u just cant.

there were wild dogs around. we never saw them, but we heard them awoo-ing a lot. so whenever someone split off from the main camp to go pee like two other girls would accompany them as an honor guard, singing Kumbaya to keep the hounds away

sometimes people would go alone and then there would be a Sound in the bush and then you’d just hear them screaming “MAMA’S MAKING KAN TONG”

on our last day the counselors set up targets with drawings of kangaroos on them, handed us a bow and 20 arrows, and said “if u can shoot the kangaroo we’ll give u sausages for your last meal”

never in my life will i ever see such ferocity from 12- to 13-year-old hungry girls again

when it was another group’s turn to be on survival, my group was on normal farm duty, and we were out clearing bush scrub when we heard the survival group girls talking and we realised we’d gotten too close.

“hello?? hello??? is anyone out there?” “oh my god someone’s out there oh my god we’re gonna die” “COME OUT, WE HAVE WEAPONS”

THIS WAS A LIE. WE KNEW DAMN WELL THEY HAD THE SAME THINGS AS US AND THOSE THINGS WERE TWO SHOVELS AND A HEAVY DUTY CLIPPER.

and our fucking counselor just went “shhh!!” to us and herded us back like he just straight up left those nine girls thinking there were bush serial killers out for them

also apparently a tree fell on someone’s head at some point in their survival

at night we slept in a row like snuggling each other cause it was So Fracking Cold and lemme tell u it’s an experience being spooned by the girl who used to sigh whenever you raised your hand in class

Four Day Hike

what it says on the label

55km in four days, carrying all your food, sleeping bags, tents, clothes, toilet paper etc. and minimum 2L of water bottles you could refill at big barrels set out at designated stop points

this is, without a doubt, the single worst experience of my life

nothing good happens when u hand a group of kids a map and a compass and tell them “we’ll look for you if you’re not at the campsite by sundown but apart from that you’re on your own”

i was with an athletic group of kids?? they were Walking So Fast and i was just staggering along with my unfit friend like this is how i die on a godforsaken hill on our way to god knows where

actually i had an asthma attack and they left me behind for a bit fun times

the hike went through some willing farmers’ land and one boy who stupidly climbed a fence got chased by a bull

they sent us off group by group so we’d all make our own way, so whenever u bumped into another group you were like. okay one of us was going the wrong way and it better fucking well be you

there weren’t any showers or anything so we basically all wore the same clothes for four disgustingly sweaty days of hiking

someone used an anthill as a toilet bc it had a nice big hole to drop ur toilet paper down

the ants did not appreciate this

when you run out of toilet paper and it’s only 11am

Solo

this was it. the culmination of the camp. the ultimate character building experience.

which was just 24 hours of alternating boredom and sudden visceral terror now that i think about it

u got dropped off (again in the middle of nowhere see a theme yet) with tarp, a lil trowel, and a clipper, and u just set up camp and did whatever u wanted for 24 hours

they let u bring a bible.

i got really into Leviticus and Deutoronomy before it went dark

listen it was really really boring ok

AND HERE IT IS THE BIT WHERE I DIDN’T HAVE LIGHT WHILE CAMPING ALONE

listen when the sun goes down at 5pm, u go down too. there’s nothing else u can do?? u just gotta sleep???

or, like me, lie awake in mortal terror listening to the bush Come Alive

when the wallaby goes THUMP-THUMP-THUMP and you’re like holy shit this is it the abominable loch ness chupycabra has manifested in the australian outback and it’s going to eat me alive jesus christ protect me with the power of this bible

hence the sheer relief when the sun finally comes out and u can walk around without living in fear of accidentally walking face first into a spiderweb or scratchy lantana bushes

also a mini survey went around afterwards and i’m pretty sure a solid 60% of the girls took a shit on solo like… at long last u can take as long in the toilet as u want… without the other 27 girls banging on the door……

other miscellaneous stories that dont fit anywhere else:

one of the boys went missing?? he wandered off and couldn’t remember anything when they found him in the middle of the bush. cryptic

there was this one homesick girl who was REALLY homesick like she cried every day of the five weeks. by the end of the camp she’d approached everyone to talk about her Feelings and you’d just kind of groan softly when u saw her coming towards your bunk bc u knew u were in for a hopeless comforting session

on sundays sometimes we went to the nearby town’s elderly home to talk to the old folks and some of us could play music so we did little performances for them which was rly sweet!

there were lambs on the farm!! we named them Uggboot and i think Fleece Jacket or smth like that

there were cows too!! meat cows!! they were Breakfast, Lunch, and Dinner

my first time on cow milking duty i tried to herd the bull towards the milking pens bc i did not realise he was not a cow. i quickly realised when he took very fast steps towards me and i Got The Dodge Out Of There

we spit roasted an entire pig for the final feast before we left and i will never forget it. the first time in my life i had crackling. half the group was weak in the knees cause we saw the pig get slaughtered and the other half was just “sweet, more for me”

whenever the new fruit delivery came in and the hunger games commenced in the kitchen… tween girls are actually ravenous wolves u heard it here first folks

when u going to the bathroom in the bush and u feel something touch your butt… is it a stray hair? is it a piece of grass? is it a bug??? who knows but nothing makes your bowels loosen faster

the unholy horror of finding spiders wherever you least expect it

ANTS IN THE SUGAR

“I saw Goody Proctor with the devil leaving the cupboard open for the ants!!!”

honestly so many things happened at Hell Camp that i can’t remember most of them anymore and it Rankles Me bc i know there were so many wild stories but here you go. some of the wildest ones.

11/10 went back to Hell Camp voluntarily once, would go back again again.

#velter answers#this took so long but is it worth it??? yes absolutely#Anonymous#hell camp#i went back to tag this just for future reference#my memories grow fuzzier by the day... hell camp deserves preservation

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Prepare Now for the Complete End of the World

OKANOGAN COUNTY, Wash. — When the end comes, some will not be waiting in a bunker for a savior. They will stride out into the wilderness with confidence, ready to hunt and kill a deer, tan its hide and sleep easily in a hand-built shelter, close by a fire they made from the force of their two palms on a stick.Four hours from the Seattle airport, in a valley called Methow, near a town called Twisp, Lynx Vilden was teaching people how to live in the wild, like we imagine Stone Age people did. Not so they could get better at living in cities, or so they could be better competitors in Silicon Valley or Wall Street.“I don’t want to be teaching people how to survive and then come back to civilization,” Lynx said. “What if we don’t want to come back to civilization?”Some people now are considering what it means to live in a world that could be shut down by a pandemic.But some people are already living like this. Some do it because they just like it. Some do it because they think the end has, in fact, already begun to arrive.

⎌

A couple of times a year, Lynx — she goes by the name professionally, though it is not her legal name — teaches a 10-day introduction to living in the wilderness. When I arrived for this program, Lynx ran to me, buckskins flying, her hands cupped tightly around something that was smoking.She held it toward my face. I closed my eyes and inhaled deeply. Confused, she moved her smoking handful to someone else, who blew on it lightly. It was an ember in a nest of seed fluff. Lynx was making fire.Her property looks like a kidnapper’s lair from a movie. But her dream, she told those of us gathered, is a human preserve. Her vision is called the Settlement. It will have a school, where people can come in street clothes and learn to tan hides. But to enter the preserve itself will mean giving oneself over to it.“You walk into it naked and if you can create from that land what that land has to offer, then you can stay there,” Lynx said. “It’s going be these feral rewilded people. I’m thinking in two to three generations there could be real wild children.”We set up our tents around her property. I had a sleeping bag from high school, a Swiss army knife and a stack of external batteries. It scared me that there was no cellphone reception. We communicated over the week in hoots. One hoot means hoot back. Two hoots means “gather.” Three hoots means an emergency, like near-death level.The class may have been there to go ancient, but they brought very modern food requests. In a group of seven, one student was a strict carnivore — Luke Utah, who likes a morning smoothie of raw milk, liver and egg yolk. Another was a vegan. One student said they were so sensitive to spice that even black pepper was overwhelming. One person was paleo, one was allergic to garlic, and one was gluten-free.Louis Pommier, a French chef turned backpacker, was bartering his skill for attendance. He nodded empathetically as he heard these restrictions but would go on to mostly ignore them. The first night he made a chicken curry.Many of the people who were there came feeling useless in their lives. Some had just quit their jobs. Lynx said many of the students who come for the monthslong intensives (another option) are divorced, or on their way to it. Several talked about feeling embarrassed at how soft their hands were, and how dependent they had gotten on watching TV to fall asleep.

⎌

We woke up the next morning and gathered around the open fire for boiled eggs. Soon we would learn how to chop down a tree. First Lynx greeted the tree. She put her hands on it.“If you’re willing to be cut down, will you give a yes?” she asked. She tugged the tree. She calls it a muscle test. Apparently the tree said yes. “We have to kill to live,” she said.Many students had brought elegant knives and axes from rewilding festivals — there’s a booming primitive festival circuit, with names like Rabbitstick Rendezvous, Hollowtop and Saskatoon Circle — but when confronted with an actual tree they didn’t want to use those. There was an old ax they used instead. Its head periodically flung off, each time narrowly missing someone. The tree eventually fell, a foot from my tent.The vibe was a mix of Burning Man, a Renaissance Fair and an apocalyptic religious fantasy. There was no doomsday prepper gun room — what would happen when bullets run out? Nor was there a sort of kumbaya, gentle-love-of-nature-yoga-class vibe. When Lynx told the story of killing her first deer, she said the deer, wounded, tried to drag herself away.We shaved off the tree’s bark and got to the cambium, the soft inner layer of bark that we would boil in water. This would be used to tan hides. We learned on supermarket salmon skin. We tore into the plastic bags of sockeye salmon with stone shards, then descaled the skin with dull bones.Lynx demonstrated how to process a deer hide using a hump bone from a buffalo. She sent us to go look for bones from the kitchen. Our job was to scrape off the muscle and fat. The hide was heavy, wet and beginning to rot.Sometimes she played a deer leg flute while we worked.That night was bitterly cold. I wore every piece of clothing I brought. Lynx coached us in warming big rocks by the fire, rotating them like potatoes, wrapping them in wool blankets. I heaved my two rocks, too hot to touch, covered in ash, into the sleeping bag with me.“Another thing you can do to make a big cozy bed is just rake a pile of pine needles and just burrow in and put logs on either end so it stays together,” Lynx said.

⎌

Lynx looks like Peter Pan, only 54 and with bone earrings. She is thin and quite beautiful, deeply wrinkled in a way that skin doesn’t usually get anymore. One day she wore red grain-on leather pants and her belt buckle was an elk antler crown. Another day it was a coat made of buffalo. She carried a Danish dagger made of a single piece of flint. On her belt was a little pouch made of bark-tanned salmon skin and deer hide holding a twig toothbrush, a sinew sewing cord and a bone needle, a piece of yerba santa for smudging.She never sat or rested on an object, even to eat. She always crouched. She ate out of a tree burl that she had hollowed into a bowl.Our clothes made a statement. We were not backpackers. No artificial colors, no carabiners and dangling straps and sexless sea foam green fleece. Here we wore tight leather pants. The whole point was to bring our animal selves here, and animal selves should attract mates.One day Lynx wanted us to go to town for groceries. She wore her skins. We smelled disgusting. In town there was a church with a billboard that read, “Alert today, alive tomorrow.” There was a yarn store called Fiber next to an antiques store advertising itself as a nostalgic journey. We wandered down the aisles reeking of rendered, rotted deer fat and smoke.“She’s like a blond-haired blue-eyed dressed up like a North American native person from a century ago, so she’s a striking image that’s easy to capture a lot of people’s attention,” Matt Forkin said. He is a hardware engineer with X, Alphabet’s experimental tech division. He has studied with Lynx, and is also now going in on some land in the Sierra Foothills with friends where they plan to go wild.There are several of these new rewilding compounds emerging. One of the larger efforts is in Western Maine, where a group is working to replicate a hunter-gatherer community. What used to be a handful of bush-craft schools to learn these skills is now an industry of hundreds.On a walk Lynx found some deer scat and handed it out, and a bit of stringy inner bark too, some dead limbs, mullein stalks. I asked what kind of plant a branch is called and she bristled.“Naming something makes people think they know it when they don’t,” Lynx said. “It’s the golden torch light spindle. That’s what it does.”A group of her former students visited with stew, and we sat around a fire. They had two young children in tow, and homemade plum mead. They started just like us, they said. They were city people, mostly from the Bay Area. I visited their enclave the next morning.

⎌

Down a dirt road, past ramshackle cabins and horses, one group of permanently rewilding people have set up a series of yurts and shelters.Epona Heathen, 33, used to have a different name and used to live in Oakland, Calif., working at a thrift store. She felt the call to wilderness while studying sociology at University of California, Berkeley.“I’m writing this paper and the chair is wobbly, and I don’t know how to fix it,” Epona said of her time in the urban world. “I’m eating eggplant, and I don’t know where it grows.”“One day I was like, ‘This is crap. We live month to month. We spend all our money on booze and coffee. We can’t save like this. We can’t live like this. We all talk about getting back to earth, but we did know anything about it.’”After some time on organic farms, they found Lynx. They decided to stay for a six-month Stone Age immersion.“We had to come with 15 tanned hides and five pounds of dried fruit and five pounds of dried meat,” she said.Her partner Alex, who is 31 and who worked at a grocery store as a wine specialist, bought a property nearby. Now about a dozen young people live there.Epona’s yurt is 16 feet around and 12 feet tall, with a small wood-burning stove. She built curved bookshelves along the wall. Most of her food and medicine is dried in jars. There is a cat named Kitty and a dog named Arrow. She identifies as an animist.“People say, ‘Oh when the apocalypse comes. …’ What are you talking about? It’s here. I’m a collapsist,” she said. “I’m not invested in maintaining the comforts we have.”The Heathens, as the group named themselves, sometimes calls the cities they came from Babylon, all the same, all fallen.The biggest challenge, they’ve agreed, is that no one around them is old.“Most of us are in our 20s and early 30s,” Epona said. “You start to see where the holes in society are, and our holes now are elders.”That night, Alex took a horse over the mountain to visit some friends, while Epona stayed behind to host. She made deer, squash, and root vegetables stew. They had vats of plum mead and got the sauna going.There are enough people on the hill for a variety of love triangles. Epona and Alex split. Now Epona is dating a young woman on the property.Alex grew up in Montclair, N.J., and inherited some money. He is bald, muscular and tattooed. He said he used to be more dogmatic about living primitive, but that is changing.“I just moved out of my yurt and into a house,” he said. “I got a second truck.”Roxanne, who is 26 and has bright curly red hair, was here for community, she said. She was working alongside Alex, rubbing salt into hides. She just moved a couple weeks ago and had been working at a coffee shop before this.“You know, the thing about living the dream is it’s really hard!” she shouted, hauling another salt bag.There is a main house down the hill, with a land line that everyone shares. The place is decorated in skulls and massive birds. There is a buffalo strung out to dry outside and a tall stack of deer legs at the door. More fit and dusty young people lounged inside. They were roasting a deer leg.A sense of collapse underlies their opposition.“From a purely rational engineering mind looking at the trends in the data, exponent times an exponent, our utilization of natural resources is way beyond the natural carrying capacity of the earth, and we’re seeing that in essentially ecosystem collapse,” Matt Forkin had told me. “In our lifetimes there is a very high chance we will see major social collapse. I do think there will come a time when these skills are practical for a large number of people.”Alex made a gesture toward the small town over the hill and down the road. “Everyone is partying their final days away,” he said.Lynx was padding around in wool in her little cottage at the end of the property. She sleeps indoors in the winter. Her home is all exposed wood and overflowing planters, horns and old rattles. She was prickly and suspicious, upset that I had left her property to visit the Heathens.Her daughter, Klara, lives in Washington, D.C. Klara’s boyfriend works for the World Bank.“When I met him,” Lynx said, “my first question was, ‘Do you hunt?’ No. ‘Do you chop wood?’ He said, ‘I could try.’”Lynx is single, and that is starting to bother her.“The hard part is finding a partner to share it with,” Lynx said. “Maybe I’m getting to the point where people get fixed in their environments.”She had a traditional childhood with traditional parents in London but left at 17 to play music. She moved to Sweden, went to art school. One day she met a man and they moved to Washington State to backpack. She went into the woods.For a while, she was married to a man named Ocean. They had Klara. She home-schooled her in the mountains in Montana, but Klara went to live with Ocean. Lynx went farther into the wilderness.But even she cannot escape money, yet. A week-long class costs $600. “I have to have my foot in two worlds to maintain some semblance of how I want to live in this world,” she said. Klara answers email for Lynx.In September, Lynx will lead another fully Stone Age project, marching into the nearby public lands. All clothes must be handmade, all food gathered.Lynx’s family still lives in London, mostly. Her sister is a freelance conservator.

⎌

We imagine that someone striking out into the wilderness is doing so to get away from everyone, to be alone. The people I met wanted the opposite. They want a life where they cannot survive even a day alone. They cannot get food alone, cannot go to the bathroom, cannot get warm alone. They want to be dependent.“The city is actually the place of rugged individualism,” said my classmate Joan, who grew up in suburban Philadelphia and uses the pronoun they. “Here I’m using my hands and with people all day.”Before being in the wild, they were addicted to video games and loved social media; very soon, Joan said, they were going to smash their smartphone. They were wearing a thick vest they had felted, with a full marten, body and head, sewn in as a collar for warmth.“Some people don’t get it, but I prefer this life,” Joan said. “No, I don’t use toilet paper. I use moss and I like it better.”Together, in the wild, everyone had to soften. One night, one of the guys said something offensive about gender roles, and a couple of us got annoyed. Then we all had to stop arguing because there was no one else to be with. I started arguing about politics with someone. Instead of going away, he had cold contraband beer, and I had nothing better to do than learn more about him. My only entertainment was the people around me. It made them more interesting.“Really coming back to nature means responding to the social responsibility too. Someone says you have this personality flaw, you can’t just avoid them. You have to respond. You adapt,” Epona said. “Rugged individualism is a lie. Rugged individualism cannot survive.”“There’s a social skill set of working in a community,” Luke Utah said.At one point, I got separated from the group. There was nothing I could do. I checked the river. I checked the houses. I checked the little pine needle burrows where people sometimes slept. I hooted once. I hooted twice. I sat and waited in a terror while it got dark.Our time makes social obligation largely unnecessary. When I moved apartments, I hired TaskRabbits. When I got cold, I turned on the heat. In the woods, the evening entertainment I got was what we could provide one another. Now, suddenly, I did not want to be alone for a minute. The dependence felt amazing. I shrieked with joy when the group came jaunting back.The next time I went to town, I dreaded the spasms of my phone wriggling back to life. I could feel the reception in the air, could feel being alone again. I was relieved to cross over the hill, out of service and back again to Lynx and my friends.Deer legs are very useful. Their toe bones can be whistles and buckles and fish hooks. The leg bones become knives and flutes. Tendons become glue. I popped the black toes off into boiling water. Slicing with obsidian, I peeled the fur off and then the muscle and tendons. I sawed the ends off the bone. I used a twig to oust the marrow. The carnivore ate it. This would be my flute.

Read the full article

#1technews#0financetechnology#03technologysolutions#057technology#0dbtechnology#0gtechnology#1technologycourtpullenvale#1technologydr#1technologydrive#1technologydrivepeabodyma#1technologydriveswedesboronj08085#1technologyplace#1technologyplacerocklandma#1/0technologycorp#2technologydrive#2technologydrivestauntonva24401#2technologydrivewarana#2technologydrivewestboroughma01581#2technologyfeaturestopreventcounterfeiting#2technologyplace#2technologyplacemacquarie#2technologywaynorwoodma#3technologybetsgenpact#3technologycircuithallam#3technologydrive#3technologydrivemilpitasca95035#3technologydrivepeabodyma#3technologydrivewestboroughmassachusetts01581#3technologyltd#3technologyplace

0 notes

Text

Ape-English Dictionary

Apes have a language that they taught to Tarzan when he was a child. That is what Edgar Rice Burroughs says, and he should know. Many of the terms are translatable into English and are used in the Tarzan books. Here is a list of ape words and their English meanings.

there is also an ape-english VOCABULARY with words organized by topic

a light || ab boy || abalu brother || abu knee (kneel) || adu lose || ala rise || amba fall || ara lightning || arad spear || argo fire || aro shoot, throw, cast || at tail || atan male

bal golden || balu baby || balu-den stick, branch, limb || band elbow || bar battle || bara deer || ben great || bo flat || bolgani gorilla || bu he || bund dead || bundolo kill || bur cold || busso fly || buto rhinoceros || b'wang hand || b'yat head || b'zan hair || b'zee foot

dak fat || dak-lul lake || dako thick || dako-zan meat, flesh || dan rock, stone || dan-do stop || dango hyena || dan-lul ice || dano bone || dan-sopu nut || den tree || dum-dum tom-tom, drum, gathering || duro hippopotamus

eho much || eho-dan hard || eho-kut hollow || eho-lul wet || eho-nala top || es rough || eta little || eta-gogo whisper || eta-koho warm || eta-nala low || etarad arrow

ga red || galul blood || gando win || gash tooth, fang || gimla crocodile || go black || gogo talk (buffalo) || gom run || gomangani negro || gom-lul river || gor growl || gorgo buffalo (moon) || goro moon || gree-ah like, love || gu stomach, belly || gugu front || gumado sick || gund chief

histah (hista) snake || ho many || hoden forest || hohotan tribe || horta boar || hotan clan || ho-wala village || ho-wa-usha leaves || hul star

jabo shield || jar strange

kagoda? Do you surrender? || kagoda! I do surrender! || kal milk || kalan female || kalo cow || kalu mother || kambo jungle || kando ant || kargo middle, center || kas jump || klu hen || klu-kal egg || ko mighty || kob hit || koho hot || kor walk || korak killer || kordo dance || ko-sabor mighty lioness || kota tortoise || kreeg-ah beware,danger || kree-gor scream || kudu sun || kut hole

lan right || lana sting || lano mosquito || lat nose || litu sharp || lob kick || lot face || lu fierce || lufo side || lul water || lul-kor swim || lus tongue

mado lame || mal yellow || mangani great apes || manu monkey || meeta rain || mo short || mu she

nala up || neeta bird || nene beetle || nesen grasshopper || no brook || numa lion || nur lie (untruth)

olo wrestle || om long || omtag giraffe

pacco zebra || pal country (tribe's hunting grounds) || pamba rat || pan soft || pand thunder || panda noise || pandar loud || pand-balu-den rifle || pan-lul weep || pan-vo weak || pastar father || pele valley || pisah (pisa) fish || po hungry || popo eat (also so) || por mate || por-atan husband || por-kalan wife

rak yes (also huh) || rala snare || ramba lie down || rand back || rea word || rem catch || rep truth || ro flower || rota laugh || ry crooked || ry-balu-den bow

sabor lioness || sato kind || sheeta panther, leopard || ska vulture || skree wild-cat || sopu fruit || sord bad

ta high, tall || tag neck || tan warrior || tand no, not || tanda dark || tandak think || tand-ho few || tandlan left || tand-litu dull, blunt || tand-lul dry || tand-nala down || tand-panda silent, silence || tand-popo starve || tand-ramba get up || tand-unk stay || tand-utor brave || tand-vulp empty || tan-klu rooster || tantor elephant || ta-pal hill || tar white || tar-bur snow || tarmangani white men || tho mouth || thub heart || tongani (tongoni) baboon || tor beast || tro straight || tu bright || tub broken

ubor thristy || ud drink || ug bottom || ugh okay || ugla hate || ungo (unga) jackal || unk go || unk-nala climb || usha wind || ut corn || utor fear, afraid

van well || vando good || ved mountain || vo muscle || voo-dum dance || voo-voo sing || vulp full

wa green || wala neat, hut, home, house || wang arm || wappi antelope || wa-usha leaf || whuff smoke || wo this || wob that

yad ear || yang swing || yat eye || yato look, see || yel here || yeland there || yo friend || yud come || yut stab, gore || yuto cut

za girl || za-balu sister || zan skin || zee leg || zor in || zu big ||

zu-dak-lul (za-dak-lul) ocean || zugor roar || zu-kut cave || zut out || zu-vo strong

0 notes

Text

4

For a few moments, Peeta and I take in the scene of our mentor trying to rise out of the slippery vile stuff from his stomach. The reek of vomit and raw spirits almost brings my dinner up. We exchange a glance. Obviously Haymitch isn't much, but Effie Trinket is right about one thing, once we're in the arena he's all we've got. As if by some unspoken agreement, Peeta and I each take one of Haymitch's arms and help him to his feet.

"I tripped?" Haymitch asks. "Smells bad." He wipes his hand on his nose, smearing his face with vomit.

"Let's get you back to your room," says Peeta. "Clean you up a bit."

We half-lead half-carry Haymitch back to his compartment. Since we can't exactly set him down on the embroidered bedspread, we haul him into the bathtub and turn the shower on him. He hardly notices.

"It's okay," Peeta says to me. "I'll take it from here."

I can't help feeling a little grateful since the last thing I want to do is strip down Haymitch, wash the vomit out of his chest hair, and tuck him into bed. Possibly Peeta is trying to make a good impression on him, to be his favorite once the Games begin. But judging by the state he's in, Haymitch will have no memory of this tomorrow.

"All right," I say. "I can send one of the Capitol people to help you." There's any number on the train. Cooking for us. Waiting on us. Guarding us. Taking care of us is their job.

"No. I don't want them," says Peeta.

I nod and head to my own room. I understand how Peeta feels. I can't stand the sight of the Capitol people myself. But making them deal with Haymitch might be a small form of revenge. So I'm pondering the reason why he insists on taking care of Haymitch and all of a sudden I think, It's because he's being kind. Just as he was kind to give me the bread.

The idea pulls me up short. A kind Peeta Mellark is far more dangerous to me than an unkind one. Kind people have a way of working their way inside me and rooting there. And I can't let Peeta do this. Not where we're going. So I decide, from this moment on, to have as little as possible to do with the baker's son.

When I get back to my room, the train is pausing at a platform to refuel. I quickly open the window, toss the cookies Peeta's father gave me out of the train, and slam the glass shut. No more. No more of either of them.

Unfortunately, the packet of cookies hits the ground and bursts open in a patch of dandelions by the track. I only see the image for a moment, because the train is off again, but it's enough. Enough to remind me of that other dandelion in the school yard years ago.

I had just turned away from Peeta Mellark's bruised face when I saw the dandelion and I knew hope wasn't lost. I plucked it carefully and hurried home. I grabbed a bucket and Prim's hand and headed to the Meadow and yes, it was dotted with the golden-headed weeds. After we'd harvested those, we scrounged along inside the fence for probably a mile until we'd filled the bucket with the dandelion greens, stems, and flowers. That night, we gorged ourselves on dandelion salad and the rest of the bakery bread.

"What else?" Prim asked me. "What other food can we find?"

"All kinds of things," I promised her. "I just have to remember them."

My mother had a book she'd brought with her from the apothecary shop. The pages were made of old parchment and covered in ink drawings of plants. Neat handwritten blocks told their names, where to gather them, when they came in bloom, their medical uses. But my father added other entries to the book. Plants for eating, not healing. Dandelions, pokeweed, wild onions, pines. Prim and I spent the rest of the night poring over those pages.

The next day, we were off school. For a while I hung around the edges of the Meadow, but finally I worked up the courage to go under the fence. It was the first time I'd been there alone, without my father's weapons to protect me. But I retrieved the small bow and arrows he'd made me from a hollow tree. I probably didn't go more than twenty yards into the woods that day. Most of the time, I perched up in the branches of an old oak, hoping for game to come by. After several hours, I had the good luck to kill a rabbit.

I'd shot a few rabbits before, with my father's guidance. But this I'd done on my own.

We hadn't had meat in months. The sight of the rabbit seemed to stir something in my mother. She roused herself, skinned the carcass, and made a stew with the meat and some more greens Prim had gathered. Then she acted confused and went back to bed, but when the stew was done, we made her eat a bowl.

The woods became our savior, and each day I went a bit farther into its arms. It was slow-going at first, but I was determined to feed us. I stole eggs from nests, caught fish in nets, sometimes managed to shoot a squirrel or rabbit for stew, and gathered the various plants that sprung up beneath my feet. Plants are tricky. Many are edible, but one false mouthful and you're dead. I checked and double-checked the plants I harvested with my father's pictures. I kept us alive.

Any sign of danger, a distant howl, the inexplicable break of a branch, sent me flying back to the fence at first. Then I began to risk climbing trees to escape the wild dogs that quickly got bored and moved on. Bears and cats lived deeper in, perhaps disliking the sooty reek of our district.

On May 8th, I went to the Justice Building, signed up for my tesserae, and pulled home my first batch of grain and oil in Prim's toy wagon. On the eighth of every month, I was entitled to do the same. I couldn't stop hunting and gathering, of course. The grain was not enough to live on, and there were other things to buy, soap and milk and thread. What we didn't absolutely have to eat, I began to trade at the Hob. It was frightening to enter that place without my father at my side, but people had respected him, and they accepted me. Game was game after all, no matter who'd shot it. I also sold at the back doors of the wealthier clients in town, trying to remember what my father had told me and learning a few new tricks as well. The butcher would buy my rabbits but not squirrels. The baker enjoyed squirrel but would only trade for one if his wife wasn't around. The Head Peacekeeper loved wild turkey. The mayor had a passion for strawberries.

In late summer, I was washing up in a pond when I noticed the plants growing around me. Tall with leaves like arrowheads. Blossoms with three white petals. I knelt down in the water, my fingers digging into the soft mud, and I pulled up handfuls of the roots. Small, bluish tubers that don't look like much but boiled or baked are as good as any potato. "Katniss," I said aloud. It's the plant I was named for. And I heard my father's voice joking, "As long as you can find yourself, you'll never starve." I spent hours stirring up the pond bed with my toes and a stick, gathering the tubers that floated to the top. That night, we feasted on fish and katniss roots until we were all, for the first time in months, full.

Slowly, my mother returned to us. She began to clean and cook and preserve some of the food I brought in for winter. People traded us or paid money for her medical remedies. One day, I heard her singing.

Prim was thrilled to have her back, but I kept watching, waiting for her to disappear on us again. I didn't trust her. And some small gnarled place inside me hated her for her weakness, for her neglect, for the months she had put us through. Prim forgave her, but I had taken a step back from my mother, put up a wall to protect myself from needing her, and nothing was ever the same between us again.

Now I was going to die without that ever being set right. I thought of how I had yelled at her today in the Justice Building. I had told her I loved her, too, though. So maybe it would all balance out.

For a while I stand staring out the train window, wishing I could open it again, but unsure of what would happen at such high speed. In the distance, I see the lights of another district. 7? 10? I don't know. I think about the people in their houses, settling in for bed. I imagine my home, with its shutters drawn tight. What are they doing now, my mother and Prim? Were they able to eat supper? The fish stew and the strawberries? Or did it lay untouched on their plates? Did they watch the recap of the day's events on the battered old TV that sits on the table against the wall? Surely, there were more tears. Is my mother holding up, being strong for Prim? Or has she already started to slip away, leaving the weight of the world on my sister's fragile shoulders?

Prim will undoubtedly sleep with my mother tonight. The thought of that scruffy old Buttercup posting himself on the bed to watch over Prim comforts me. If she cries, he will nose his way into her arms and curl up there until she calms down and falls asleep. I'm so glad I didn't drown him.

Imagining my home makes me ache with loneliness. This day has been endless. Could Gale and I have been eating blackberries only this morning? It seems like a lifetime ago. Like a long dream that deteriorated into a nightmare. Maybe, if I go to sleep, I will wake up back in District 12, where I belong.

Probably the drawers hold any number of nightgowns, but I just strip off my shirt and pants and climb into bed in my underwear. The sheets are made of soft, silky fabric. A thick fluffy comforter gives immediate warmth.

If I'm going to cry, now is the time to do it. By morning, I'll be able to wash the damage done by the tears from my face. But no tears come. I'm too tired or too numb to cry. The only thing I feel is a desire to be somewhere else. So I let the train rock me into oblivion.

Gray light is leaking through the curtains when the rapping rouses me. I hear Effie Trinket's voice, calling me to rise. "Up, up, up! It's going to be a big, big, big day!" I try and imagine, for a moment, what it must be like inside that woman's head. What thoughts fill her waking hours? What dreams come to her at night? I have no idea.

I put the green outfit back on since it's not really dirty, just slightly crumpled from spending the night on the floor. My fingers trace the circle around the little gold mockingjay and I think of the woods, and of my father, and of my mother and Prim waking up, having to get on with things.

I slept in the elaborate braided hair my mother did for the reaping and it doesn't look too bad, so I just leave it up. It doesn't matter. We can't be far from the Capitol now. And once we reach the city, my stylist will dictate my look for the opening ceremonies tonight anyway. I just hope I get one who doesn't think nudity is the last word in fashion.

As I enter the dining car, Effie Trinket brushes by me with a cup of black coffee. She's muttering obscenities under her breath. Haymitch, his face puffy and red from the previous day's indulgences, is chuckling. Peeta holds a roll and looks somewhat embarrassed.

"Sit down! Sit down!" says Haymitch, waving me over. The moment I slide into my chair I'm served an enormous platter of food. Eggs, ham, piles of fried potatoes. A tureen of fruit sits in ice to keep it chilled. The basket of rolls they set before me would keep my family going for a week. There's an elegant glass of orange juice. At least, I think it's orange juice. I've only even tasted an orange once, at New Year's when my father bought one as a special treat. A cup of coffee. My mother adores coffee, which we could almost never afford, but it only tastes bitter and thin to me. A rich brown cup of something I've never seen.

"They call it hot chocolate," says Peeta. "It's good."

I take a sip of the hot, sweet, creamy liquid and a shudder runs through me. Even though the rest of the meal beckons, I ignore it until I've drained my cup. Then I stuff down every mouthful I can hold, which is a substantial amount, being careful to not overdo it on the richest stuff. One time, my mother told me that I always eat like I'll never see food again. And I said, "I won't unless I bring it home." That shut her up.

When my stomach feels like it's about to split open, I lean back and take in my breakfast companions. Peeta is still eating, breaking off bits of roll and dipping them in hot chocolate. Haymitch hasn't paid much attention to his platter, but he's knocking back a glass of red juice that he keeps thinning with a clear liquid from a bottle. Judging by the fumes, it's some kind of spirit. I don't know Haymitch, but I've seen him often enough in the Hob, tossing handfuls of money on the counter of the woman who sells white liquor. He'll be incoherent by the time we reach the Capitol.

I realize I detest Haymitch. No wonder the District 12 tributes never stand a chance. It isn't just that we've been underfed and lack training. Some of our tributes have still been strong enough to make a go of it. But we rarely get sponsors and he's a big part of the reason why. The rich people who back tributes - either because they're betting on them or simply for the bragging rights of picking a winner - expect someone classier than Haymitch to deal with.

"So, you're supposed to give us advice," I say to Haymitch.

"Here's some advice. Stay alive," says Haymitch, and then bursts out laughing. I exchange a look with Peeta before I remember I'm having nothing more to do with him. I'm surprised to see the hardness in his eyes. He generally seems so mild.

"That's very funny," says Peeta. Suddenly he lashes out at the glass in Haymitch's hand. It shatters on the floor, sending the bloodred liquid running toward the back of the train. "Only not to us."

Haymitch considers this a moment, then punches Peeta in the jaw, knocking him from his chair. When he turns back to reach for the spirits, I drive my knife into the table between his hand and the bottle, barely missing his fingers. I brace myself to deflect his hit, but it doesn't come. Instead he sits back and squints at us.

"Well, what's this?" says Haymitch. "Did I actually get a pair of fighters this year?"

Peeta rises from the floor and scoops up a handful of ice from under the fruit tureen. He starts to raise it to the red mark on his jaw.

"No," says Haymitch, stopping him. "Let the bruise show. The audience will think you've mixed it up with another tribute before you've even made it to the arena."

"That's against the rules," says Peeta.

"Only if they catch you. That bruise will say you fought, you weren't caught, even better," says Haymitch. He turns to me. "Can you hit anything with that knife besides a table?"

The bow and arrow is my weapon. But I've spent a fair amount of time throwing knives as well. Sometimes, if I've wounded an animal with an arrow, it's better to get a knife into it, too, before I approach it. I realize that if I want Haymitch's attention, this is my moment to make an impression. I yank the knife out of the table, get a grip on the blade, and then throw it into the wall across the room. I was actually just hoping to get a good solid stick, but it lodges in the seam between two panels, making me look a lot better than I am.

"Stand over here. Both of you," says Haymitch, nodding to the middle of the room. We obey and he circles us, prodding us like animals at times, checking our muscles, examining our faces. "Well, you're not entirely hopeless. Seem fit. And once the stylists get hold of you, you'll be attractive enough."

Peeta and I don't question this. The Hunger Games aren't a beauty contest, but the best-looking tributes always seem to pull more sponsors.

"All right, I'll make a deal with you. You don't interfere with my drinking, and I'll stay sober enough to help you," says Haymitch. "But you have to do exactly what I say."

It's not much of a deal but still a giant step forward from ten minutes ago when we had no guide at all.

"Fine," says Peeta.

"So help us," I say. "When we get to the arena, what's the best strategy at the Cornucopia for someone - "

"One thing at a time. In a few minutes, we'll be pulling into the station. You'll be put in the hands of your stylists. You're not going to like what they do to you. But no matter what it is, don't resist," says Haymitch.

"But - " I begin.

"No buts. Don't resist," says Haymitch. He takes the bottle of spirits from the table and leaves the car. As the door swings shut behind him, the car goes dark. There are still a few lights inside, but outside it's as if night has fallen again. I realize we must be in the tunnel that runs up through the mountains into the Capitol. The mountains form a natural barrier between the Capitol and the eastern districts. It is almost impossible to enter from the east except through the tunnels. This geographical advantage was a major factor in the districts losing the war that led to my being a tribute today. Since the rebels had to scale the mountains, they were easy targets for the Capitol's air forces.

Peeta Mellark and I stand in silence as the train speeds along. The tunnel goes on and on and I think of the tons of rock separating me from the sky, and my chest tightens. I hate being encased in stone this way. It reminds me of the mines and my father, trapped, unable to reach sunlight, buried forever in the darkness.

The train finally begins to slow and suddenly bright light floods the compartment. We can't help it. Both Peeta and I run to the window to see what we've only seen on television, the Capitol, the ruling city of Panem. The cameras haven't lied about its grandeur. If anything, they have not quite captured the magnificence of the glistening buildings in a rainbow of hues that tower into the air, the shiny cars that roll down the wide paved streets, the oddly dressed people with bizarre hair and painted faces who have never missed a meal. All the colors seem artificial, the pinks too deep, the greens too bright, the yellows painful to the eyes, like the flat round disks of hard candy we can never afford to buy at the tiny sweet shop in District 12.

The people begin to point at us eagerly as they recognize a tribute train rolling into the city. I step away from the window, sickened by their excitement, knowing they can't wait to watch us die. But Peeta holds his ground, actually waving and smiling at the gawking crowd. He only stops when the train pulls into the station, blocking us from their view.

He sees me staring at him and shrugs. "Who knows?" he says. "One of them may be rich."

I have misjudged him. I think of his actions since the reaping began. The friendly squeeze of my hand. His father showing up with the cookies and promising to feed Prim. did Peeta put him up to that? His tears at the station. Volunteering to wash Haymitch but then challenging him this morning when apparently the nice-guy approach had failed. And now the waving at the window, already trying to win the crowd.

All of the pieces are still fitting together, but I sense he has a plan forming. He hasn't accepted his death. He is already fighting hard to stay alive. Which also means that kind Peeta Mellark, the boy who gave me the bread, is fighting hard to kill me.

0 notes