#and as such the questions arise and real world frames of reference can be drawn.

Text

… It just occurred to me.

Dogs can’t distinguish the color red.

Is Komugi aware she is pink?

And if she is, how disorienting is it to be able to change species and suddenly see a new range of colors?

While we’re at it if she does have human color vision she’s also not going to see as much of the ultraviolet spectrum as she can before and.

Like I don’t expect this show to go even as far as your average Animorphs book in terms of the Differing Primary Sensations of different species and how strange it would be to suddenly adapt to having a weaker sense of smell and different vision priorities and different audible range in, you know, the middle of battle, much less making a statement about the natural variation in human abilities but like.

I do have questions here.

#precure spoilers#wonderful precure#komugi inukai#cure wonderful#look it doesn’t bother me when it’s Ellen because she’s a magical fairy cat. maybe they have human senses by default.#Ciel Rio Pekorin all likewise fairies who knows what their senses are like.#Yukari only turns into a cat once and there is magic involved and I think it’s her crystal animal so again. makes sense that there’s magic.#Tsubasa has always been a bird-human shapeshifter. Yuni’s always been a Rainbownian shapeshifter.#they are used to such things.#BUT THIS IS A NORMAL FUCKING DOG CAT AND PROBABLY BUNNY#and as such the questions arise and real world frames of reference can be drawn.#… oh also the hamsters. I never watched Hugtto I have no idea what’s going on with the hamsters. that’s just weird like. fundamentally.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

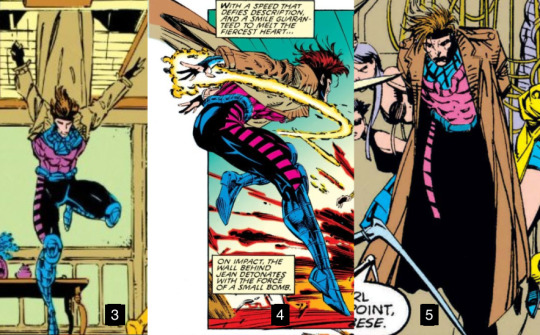

X-uniforms: Gambit edition

See here for X-uniforms: Nightcrawler edition.

By 1990, Logan had long been a reformed hero with a heart o’ gold, so a new bad boy seemed necessary. And, boy, did Jim Lee deliver. Gambit’s uniform made clear he was the new X-antihero, swooping in to dazzle every eye and sear every retina.

I won’t bash the lack of functionality to Gambit’s uniform. Cosplayers, who know best, have done so trenchantly, one of whom I quote: Gambit’s “costume not only fails to complement his role [as a thief], it actively opposes it.”

But if you’ve ever wondered why this uniform, this post attempts to explain the uniform from an artist’s POV; what it reveals about Gambit’s role in the team; why hot pink; and how three artists handle the uniform (and the man). I will focus primarily on his co-creator’s, Jim Lee’s, 1991 depictions.

LET’S PLAY SPOT THE CAJUN

How do you find a fave character when they’re swinging thru images as busy as these 90s covers?

In the same way we seek out Waldo’s striped shirt, we seek out a character’s identifying markers, or main attributes. You know it’s Cyclops when you see a white guy in red glasses or a visor. You know it’s Jean when you see a woman with red hair. Simple.

But the later a character enters a franchise, the more markers they need to distinguish themselves from the earlier, more “basic” characters. Red-haired, green-eyed Rogue needed that skunk stripe to distinguish herself from red-haired, green-eyed Jean.

By the time the 90s roll around, white guys like Gambit and Cable verge on being overdesigned—some might argue they are. Consider all the identifying markers that make Gambit Gambit:

1-Hot pink chest, pink-striped legs;

2-Reticulated metal boots;

3-Head sock;

4-Fingerless gloves—which fingers depends on the artist!

5-Duster.

Various accoutrements:

6-Cards;

7-Bo staff;

8-Cigarette.

Distinctive physical features:

9-Black-red eyes;

10-Unruly auburn hair /ponytail /mullet;

and you’ve got a superhero with a lot to identify him with. Head to metal toe. This is meant to serve the reader: Even if you saw only his crotch in a 2-inch frame, you would know it’s him, thanks to the metal boots and trench coat, or psychedelic combo of hot pink and turquoise.

Therefore, no matter how hidden his figure or from what angle, you know who it is and where he is. And that’s the whole point of this. Graphic design trumps beauty and practicality. In the comics world, anyway.

THE DUSTER

The question then arises: How are all these elements united coherently? How does Lee pull off 10 different identifying markers without making a mess?

This uniform has stood the test of time. With a few exceptions, Gambit has worn essentially the same uniform since his introduction. Much of its success has to do with the duster—because visually a duster makes miracles.

Want to dazzle your readers with Gambit’s physical might? Give us fig. 3. The capelike duster rises in a column above him, nearly doubling his size. Infinitely voluminous, it claims plenty of visual real estate, even when Gambit’s relegated behind other characters, which he often is (note figs. 1 and 2).

Want to show off his athleticism? Give us fig. 4, where his body shoots out of the duster like a Roman candle. Or a gun from a brown-paper bag.

Want to show us a man o’ mystery? Give us fig. 5, where the duster shrouds him in moody, Batman-like gravitas.

Conveniently, this coat reveals as little or as much of Gambit’s peacock-like colors and peacock-like persona as the writing demands. More significantly, it reveals something fundamental about his character: his (former) reluctance to be a superhero—so much so that he’s thrown a giant coat over his X-uniform. Unlike Rogue’s bomber jacket, which sports X-insignia on both shoulders, this duster is unaffiliated.

Ultimately, the duster signifies Gambit’s antihero status: It’s both a flag of heroism and a metaphor for Gambit’s shadowy past. And it’s become so a part of Gambit that to see him without it is off-putting.

WHY PINK? (Even Dazzler don’t wear pink.)

My crackpot theory: Superhero villains often wear secondary colors: purple, green, orange. Think Magneto’s beautiful purple outfit, Sentinels in purple, Juggernaut in orange, Dr. Doom in green. Even Rogue’s green uniform refers her former villain status. This practice was more common in the Silver Age, but it’s likely true for Gambit too. Gambit probably started out in what was meant to be purple (see fig. 6 below).

This shifts to pink when he joins the X-men (compare figs. 6 and 7). Color printing was quite limited in 1991, so bright pink may have been a cheaper option. And cheap is important for cast member who shows up in every single issue, unlike a villain. So my crackpot theory? Pink was cheaper.

I want to praise pink’s utility for a second. Those aerobics-leotard leg stripes are edited out in later years (see fig. 8). But you can see what excellent graphic work they do in figs. 2–5: They give his body a fluidity and grace, because you can track the turn of his pink hips from his pink torso. If Gambit’s power is about energy, those leotard legs are a good visual representation of the kinetics of the human body.

THREE VISIONS OF GAMBIT, COMPARED

Impractical, bright as hell, the uniform is iconic. Fig. 6, by Mike Collins, from 1990, is of Gambit’s first appearance, and fig. 7, drawn by Lee, is from 1991. Fig. 8 was published exactly 20 years later, and you’ll note the uniform is tweaked but remains largely the same.

To my eye, fig. 6’s uniform appears less outlandish than 7’s, because Collins’s work is cartoonier—that is, his head and shoulders are oversized in the way children’s cartoon characters’ are. Gambit looks like a film-noir private eye who wandered into aerobics class—and because the style is more childish, we’re more forgiving of a nonsensical imagination.

On the other hand, Lee’s image is a perfect collision of 90s self-seriousness and 90s gaudiness. Straightaway you can see that though this art is no less exaggerated, it is gritty and more “adult.” Gambit is hyperbolically macho, with gleaming abs, a clenched fist, and small-head-giant-body proportions. This is no private eye but a macho-man brooding over his own sad story . . . in turquoise boots.

Marco Checchetto’s 2010 Gambit borrows the romance of fig. 7—flowing hair— without the self-seriousness. This Gambit looks like he might actually be winsome and witty, thanks to his loose body posture.

Notice that Checchetto removes some of the macho signifiers: no more abs, no more breastplate, much narrower shoulders. In this, he gets something right about Gambit that Lee misses: Gambit’s ’tude isn’t in his abs or his metal boots; it’s in his swagger.

So I’m not as impressed with Lee’s burly portrayal, well-known as it is. It’s striking, it conveys physical power; it doesn’t evoke the unpredictability or wiliness of our hero’s nature. Mike Collins nails it the first time around, and that’s impressive, even if his Gambit is not the handsome romantic lead we’ve come to expect.

CREDITS

“Gambit: Best Worst Costume Ever.” Ryan. Mad Art Lab. http://madartlab.com/gambit-best-worst-costume-ever/

Uncanny X-men #266 (1990)

Pencils: Mike Collins

Colors: Brad Vancata

X-23 #4 (2010)

Pencils: Marco Checchetto

Colors: John Rauch

X-men #1, 5, 9, 10 (1991, 1992)

Pencils, finishes: Jim Lee

Colors: Joe Rosas

#gambit#remy lebeau#x-men uniforms#x-men costumes#x-men looks#jim lee#joe rosas#mike collins#brad vancata#marco checchetto#john rauch#mad art lab#formal analysis#antihero#90s x-men#90s comics

183 notes

·

View notes

Text

Textile Intelligence, a Social Row Material - Juniper Publishers

Abstract

Fashion futurists predict, among other things, that the ritual of standing before the mirror will be replaced by new dressing mechanisms when using intelligent textiles to obtain an aptly designed covering. A value-minded perusal of the new realms of consciousness and conceptualization generated by smart textiles calls for advanced study based on theories of sustainable planning and material culture, striving to measure and examine the influence of smart textiles on the environment and on the users. Will the need to dress each time anew be eliminated, or will users adopt new perceptions regarding the limits of human ability? These questions reinforce the argument that cultural and social changes may be introduced via textile intelligence. A journey into the unknown of solar shirts with a refreshable cut and grows able seasonal sleeves, explores the possibility of their becoming the commons, as well as the cost of their accessibility.

Keywords: Textile Intelligence; Material culture; Fashion; Sustainability; Social change

Introduction

Fashion as means of communication produces meanings, establishes aesthetic values and maintains power relations within culture. A fashion reality influenced by the possibilities of mass production and globalized economy becomes public domain within the span of a single sunrise. Implementing intelligent textiles in clothing/fashion can turn the scientific development into an integral part of the routine for the majority of material and conceptual culture consumers the world over. It might then shift control over the new opportunity of using smart textiles, to the wider public, defining new common capital that could possibly leverage a socio-cultural change [1].

A theoretical basis in support of the argument that social and cultural changes may be introduced via ‘very smart textiles’. Charging of textile intelligence with the dimensions of reality is performed by designers, manufacturers, material researchers, technologists, engineers, and industrialists [2]. Will their meticulous heritage become a passing research episode in the future which will merely provide a pointed scientific response to the field of development, or will it help promote a change in economic and social states of mind, transforming smart textiles into the norm for the majority of consumers of material and conceptual culture worldwide?

I argue that such change requires research based on theories of sustainable planning which ethically examine phenomena expected to significantly influence the majority of mankind «upstream» in the future [3]. The validity of such a discussion will form the basis for comprehensive future research aimed at pinpointing processes that may introduce social and cultural change and offering guidance for the production of smart textiles.

In order to reaffirm this working claim, the discussion should center on the points shared by the technological vision of smart textiles and contemporary social, cultural and environmental theories referring to the future and its characteristics.

Textile as a Cultural Signifier

Textiles have alluded to material culture for nearly 11 millennia (Figure 1) The roots of the metaphor «text and textile» point at a material characterized by intertwined technical and cultural aspects. The conceptual perception of these two cultural milestones has spawned languages of communication transpiring along common axes that have drawn meanings and symbols from each other [4]. Textile as a text of fashion functions as a bridge between material culture and visual meaning, from the definition of identity and the structuring of social status to an inter textual work comprising virtual images [5]. The experience of social liberation has been transformed from a personal asset to an economic commodity in the fashion world (Figure 2 & 3). A multi-dimensional weaving technology embeds text into textile, converting the body, in the service of fashion, into an unequivocal time- and gaze-dependent frame.

Go to

Intelligent and Interactive Textiles

Xiaoming Tao [2] claims that smart technologies and materials is one of the convergence results of sciences. He describes fabrics capable of sensing and responding to stimuli due to their structure. Sensors are incorporated into the cells of smart and active systems, which identify a phenomenon, convert it into movement, a chemical change, a composition, adapting or reproducing an apt response [6-8]. Very smart materials react and initiate action from a set of pre-programmed instructions. Such units possess cerebral abilities: cognition, logic, and decision-making ability.

Lena Berglin [9] discussed smart textiles and their predicted future influence on everyday life, specifying major areas of development. According to Berglin, the interdisciplinary professions associated with such developments include textile technology and design, computing technology: hardware and software, material science, signal processing, product design, interaction, and system design. This widespread trend does not include ecologists, sociologist, fashion designers and other professions that might consider non-physical aspects of intelligent textile development.

Social and Cultural Psychology of Textiles

Many parts of our physical world hold no ethical significance for us. Our awareness of the elements comprising the material environment usually amounts to an understanding of their function or an assessment of their visible and marketed quality. Enlightened contemporary use defines that the designed and fashionable are preferable, more convenient and pleasurable to live around, they convey up-to-datedness and make for safe social positioning. Further to this reality the meaning of apparel is examined in the equation of self-definition and within the social and reflexive configuration of a life borrowed from visual images.

Theories challenging prevalent cultural perceptions of body and identity likewise postulate that fashion is a dissemination route for dialects of information. Irit Rogoff [10] maintains that apparel is a language of communication [11]. Judith Butler regards apparel as a vehicle for the construction of identity. Holly L Schrank [12] chose the diffusion of fashion innovations and inventions as the object of a study which examined psychological, sociological, and economic variables. It is only natural to assume, she argues, that these processes are also relevant in practices of social admission and rejection in local systems.

Discussion

From a socio-cultural point of view, intensive assimilation of textile intelligence in fashion may dictate new boundaries for the creation of personal identity, change the body fostering culture, the sense of social belonging, and violate the balance underlying the triad: production-consumption-fashion. In this context, mutually-dependent major dilemmas are on the agenda today: one concerns the gap between the technological vision of dirtrepellent, memory-possessing, temperature-sensitive textiles, and the major axioms of consumerist culture (Figure 4); the other involves the influence of excessive intelligence in smart fabrics on the equation of human apparel (Figure 5).

It is an exploration of the journey into the body’s spraying to obtain an aptly designed covering (Figure 6) and the unknown or the accessibility of the virtual dress skills. An enchanting possibility is introduced by the contemplation of solar shirts which refresh their cut in real time, rendering their wearers independent of the stylistic aspect. Growable seasonal sleeves may engulf the wearer with a previously unfamiliar cultural and social bubble. A sweat-preventing shirt or a «forever-white» collar is bound to challenge the human consumerist urge, while being congruent with and enhancing the green inclination of restrained consumerism.

The cyclical trickling of fashion products into the garment fields cannot blur the radical dichotomy between the two target audiences: those using apparel as body covering versus the consumers of fashion. One can hardly expect that the design of innovative solutions involving smart textiles will suppress the immanent human need for innovation. It is unlikely that the northern, white world will set the challenge for itself to define a timeless language of design which will dictate the possibility for a total garment to last a lifetime. It is, however, quite likely that the rest of the world’s population will use such an intelligent garment as an existential solution, and it is also likely that then the relative size of this segment of the world’s population will shake the balance of commercial currency.

If «The Shirt» can balance the wearer into a condition of month-long satiation by epidermal diffusion of concentrated food, for example, two concepts will be realized: the supercultural concept adhering to «comfort foremost,» and dismantling individual responsibility to the point of loss of control over substantial processes. These two side-effects are incongruent with the vision of life in a sustainable world. For disaster-stricken areas, however, «The Shirt» offers a real solution. Age-dependent clothing, as well as domestic textile, resistant to both dirt and wear, can alter the time division in the maintenance of the family unit, and redundify the washing machine. As the production costs of cellular communications technologies are expected to drop, it will be possible to reproduce a communicative solution in every random button. In such a case the need will arise to settle the dispute of one-time use with the demand to restrict the use of the earth’s resources and represent the interests of the next generations.

Toward an era of life in a sustainable world, Bill McDonough & Michael Braungart [13] suggest regarding the environmental issue as a design issue. Only if the design process takes heed of the practical, ideological, visual, and latent implications can the solution become an agent of social and environmental change [14-15].

Conclusion

Contemporary theories of material culture adhere to sustainable approaches on one hand, and on the other to the demand to harness æsthetics as an agent conducive to change in social space, rather than regard the future as an unknown scientific variable. Intelligent textiles may offer an opportunity for protected, independent life for the majority of people as an existential basis.

Hypothetically, one may see how the transformation of the notion of wash-and-wear into self-cleaning or no-wash clothing and mass production of dirt-repellent, wear-resistant textiles may introduce a change in the equilibrium of the fashion industry and interfere with the profitability of the corporate economy.

The intricate nature of intelligent applications in textile is bound to add yet another set of signs and meanings to the restricted discourse of apparel and the broader discourse of culture on high levels of freedom and define realms of awareness and action infused with additional dimensions. These realms of awareness and conceptualization are a cultural raw material which may be owned, calibrated, guided, and aimed at goals oriented at human society as a whole. The right of ownership to the assets of this technological development must be ruled in favor of the general public to ensure a change and prevent cynical use which will exploit the public.

Economic control of smart textiles will dictate new orders, relationships, and hierarchies, and will profit from the dissociation between ownership of the technology and the ownership over the cultural priorities. Technological research must harness itself to cast a social anchor that will provide innovation with a cultural, philosophical, and conceptual grasp more significant than the analysis of profit.

More than a mere technological possibility and industrial realization, the vision of smart-textile as social raw material aims at empowering the users, furnishing them with a vehicle which will re-define their social and cultural positioning and shift the gaze directed at them outside the classification of the allowed and possible.

Scholarly backing is required in order to predict the change in the patterns of visibility, behavioral modes, life style, and social structures accompanying the use of very smart textiles. Even perceptual norms may deviate from their natural boundaries and adopt irrational insights regarding the dimensions of human capacity or suffering.

To know more about Journal of Fashion Technology-https://juniperpublishers.com/ctftte/index.php

To know more about open access journals Publishers click on Juniper Publishers

#fashion technology#textile engineering#Juniper Publishers#Juniper Publishers e-pub#Juniper Publishers group

0 notes

Text

The Circle and the Square -- Temple and Cosmos Beyond this Ignorant Present -- HUGH NIBLEY 1992

The Circle and the Square

What exists on the earth’s surface is supported, much like a troupe of actors, by countless backstage assistants. I’ve often referred to the earth as a stage, to which Joseph Smith gives us the scenario. He talked about the stagehands, forming a network that extends far behind and beyond the theater walls. The props and the stage are there, along with the stagehands. The big question is, Is there a play? Is there a plot? Is there a meaning to it all?

Surprisingly, since ancient times, only Joseph Smith has come up with any kind of a plot. When he faced the world he had nothing to go on, and everything against him; he couldn’t lose. He had something concrete to put up, while the rest of the world had none. They had the abstract, the moralistic, etc., but nothing in the way of the infinities, of the realities of the next world. Only Brother Joseph had something to offer.

Certainly the earth is not the center of the universe. This illusion has been discarded forever. Still, this crowded earth is one of those perhaps innumerable places in the cosmos where both life and consciousness flourish. Many factors united to produce and maintain the right conditions where life was generated by a concentration of mighty forces upon one relatively tiny point.

This is the center I am talking about, and it’s exactly what we read in the book of Abraham, where he says that everything is relative to the individual: the individual is the center. All distances, all times, all places are measured in terms of the “[earth] upon which thou standest” (Abraham 3:5). Its distances, its motions, etc., are not the center of anything. Moses says the same thing: “Tell me, I pray thee, why these things are so” (Moses 1:30). The Lord replies: I’m not going to. “Only an account of this earth . . . give I unto you” (Moses 1:35). You must be content with that, but remember that there are others: “Worlds without number have I created” (Moses 1:33).

“Tell me concerning this earth,” Moses returns. “Then thy servant will be content” (Moses 1:36).

So for us, the earth is the center of things, so long as we’re here.

There arises the question of whether we need a psychological center—some kind of center we can refer to. Thus we frequently quote Yeats’ famous lines: “Things fall apart; the center cannot hold; mere anarchy is loosed upon the world.”1 Our civilization is collapsing, falling apart, because there is no center; everything is loosened.

In the opening lines of the famous first of modern geography books, Ratzel begins, “Every man regards himself as the center of the universe around him.” There is a real center, but it is also relative. There is also each person’s awareness that other people have their centers too, unless you’re a solipsist, or something similar. Since there are other people, there must be other centers. For the purposes of getting together, can we agree on one center—a fictitious center, a model of some sort, and act as if that were the center?

Actually we don’t have to do that, because we have one very real center. If you traveled over the entire earth viewing the heavens, you wouldn’t come to a center, but you would find two places that looked very much alike: the center polestars, of course. They stay fixed, while all else revolves around them. Thus on the west tower of the Salt Lake Temple there is the Big Dipper, pointing up—to the polestar.2 The temple is a point of reference, a place where you take your bearings on the universe.

That’s what the word templum means. Everyone knows what a template is that you put over a map. It’s as if we put a template over the temple in Salt Lake City; most every street in the city, and every city in the state, is measured east, west, north, and south from that arbitrary point. (Certain points on the earth do seem to be particularly suited as central points—they have a special power, charm, or attraction about them.)

So are we there among the stars, or are we not? Giorgio de Santillana said we should not be too sure we aren’t.3

Our present tradition comes from the great migrations, after some kind of Golden Age, which broke up around 3500 to 3000 B.C. This was a horrible time; everything went to smash. Everything was uprooted; everyone became migrants. And, obsessed with the idea of the temple, they took it with them—though it was a different concept from the older, permanent idea. When people are uprooted, they develop two yearnings: a passion for permanence, and a zest for distance and adventure.

As we see in the Odyssey, Odysseus, who wandered for ten years, enjoyed his journey, at least with Calypso. She twitted him about it. Still he blubbered all day long to be home with his dear wife. He loved to travel, but he couldn’t wait to get home. He had to have both. It is like a French geographer’s description of the mad force of the sun and the wise force of the earth. The latter pulls you back, although you want both. This is what our ancestors documented in the great migrations.

Ancient tribal shrines of the Near East are known variously as the cutfa (“the standing place”), the mahmal (“a wagon, or something you ride in”), the markab (“a camping place”), a qubba (“dome, or navel center—something that doesn’t move, like a Navajo hogan”), a bayt (a place where you spend the night only—our words booth, abide, etc.), a Hebrew ‘arôn (“an ark or vessel, like the ark of the covenant”), and an Arabic tabut (borrowed from the Egyptian word for “chest, coffin”)—all these words designate the ancient tribal shrines.4 And they have two characteristics in common: they are dome-shaped, and they are mounted on a boxlike frame; the two come together in a substructure, merkabah, a vessel or wagon (something you ride on). The word has a great mystical meaning in the Jewish cabbalistic literature. The merkabah is the vessel by which God conveys his wisdom, whatever it might be, to whomever. Whatever its precise meaning, it was meant to provide mobility.

Two recent studies discuss the cosmic nature of the wheel, the dome-shaped shrine, or royal balde, baldekin or baldaekin, or, paradoxical as it may seem, such a symbol of supreme stability as the throne, temple, holy city and even sacred mountain. World mountains are often depicted as revolving wheels or as mounted on wheels.

That’s a strange thing. The Roman quadrata represents the four corners of the earth, and the center of everything; the Romans always drew it this way. But it’s also the picture of a wheel. The Babylonians combined the two very neatly in their cosmic design. It’s the wheel that goes round and round but never moves.

For the nomads, it’s a qubba—a dome; the Latin word is cupola: a cap, cup. It represents the dome of the heavens, and you find it everywhere as the common shape of churches. And the square church accompanies it. The dome, like a stupa in India, is mounted over a perfect cube. To the nomads the qubay, or domed red leather tent of the chief, is the qubba.

The Islamic qibla derives from a root meaning “to face, to receive, to look toward.” When a Muslim prays five times a day, what direction does he face? To Mecca—the center of the world. How does he know where the center is? In his house he has a qibla, a marker that tells the direction he must face, “by which the tribe when it camps, takes its bearings in space; the qibla itself is oriented with reference to the heavenly bodies. For the Asiatics as well as the Romans, the Royal Tent is a templum or tabernaculum.”5

The word tabernaculum is the Roman name for a quickly made booth, a “little house of boards,” something thrown up very quickly of brush, boards, blankets, or anything you might happen to have.6 The Feast of Tabernacles is the sukkôt of the Hebrew, which is the sh of the Egyptians.

It’s the same thing as the outer court of the Greek temple, the temenos, which means “temple,” “to cut”—the point at which the two lines, the cardo and the decumanus, intersect (the axis mundi).7 All space comes together at this absolute, theoretical, perfect point. It is the center of everything, which doesn’t exist. It’s like the singularity that physicists talk about today—things that are real and conceivable, but not describable. Thus it’s a device for taking our bearings on wherever we are. That’s precisely what a temple does: it puts us into the picture of time and space. It’s a sort of sacred observatory, like the tabernacle or the camp of Israel, and at the same time a kind of planetarium, a model of the cosmos.8

The temple at Jerusalem was built to accommodate the ark of the covenant. The ark, ‘arôn, could travel in a tent, because it does travel. Even when housed in Solomon’s temple, the ark had the carrying poles on it, so it could be carried around. It resembles an archaic Egyptian shrine, even to the details.

This double quality (the ever-moving center) caused much dispute among the Doctors of the Jews. Some said that a stone temple that tied down the ark, and hence the chosen people, was an abomination; others said it was the very symbol of endurance and everlasting assurance.9

The central pole of the tent (see Eliade’s work on Shamanism)10 is often identified with the pole (the polestar) of the heavens. “The tent itself is the Weltenmantel, the expanse of the firmament. Other tent poles sometimes represent the four cardinal points or the two turning points of the sun in the summer and winter solstice.”11 The tent pole theme is carried over into the pillars of the temples and palaces, even into the columns of medieval churches and the stately façades of our own public buildings.”12 Thus we all are familiar with the idea.

There are two kinds of temple architecture—the circle and the square. The earliest nine pyramids along the Nile were perfectly square. When I checked this in my pyramid texts, the symbol was drawn thus. At Gilgal twelve stones stand in a circle. Generally, the rites are said to be in the form of a circumambulation. The king goes through the land in a great circle, in his Royal Progress, the “king’s tour.” He visits one by one each holy place, to take possession of his land, something he has to do every year. When he arrives at each, he circumambulates it three times. That’s the combination: the circle and square.13

In the Pythagorean mystic, the cube represents perfect solidity; the sphere is perfect continual motion. The two must always be together; thus we find them so combined in ancient temples, and in our temple too. The Manti Temple features the square building, but it has a circular staircase. The Provo Temple has a square bottom, but is rounded off (it would have been nice had they made up their minds whether they wanted it square or round). It looks like a typical “stupa.” And of course it has a tall, round ornament at the top. There is always motion around, but also always stability in the center. It is satisfying to have it both ways.

For this reason, the temple lends itself to duplication, an important principle. The ancients often referred to it as “the spark.” We are now into the mechanics of the creation process.

All ancient temples rehearsed the story of the creation, and the establishment of mankind and royal government of God upon this earth. Then they moved into the heavenly sphere and the theology associated with the worlds beyond.

The order and stability of a foundation are achieved through the operation of a “spark.” The spark is sometimes defined as “a small idea.”14 This is interesting, because it reminds us of a contemporary anthropic idea. “That comes forth from God and makes all the difference between what lives and what does not.”15 This spark must go from world to world, and wherever it goes, it sets up a new center; this center in turn goes out and sets up other new centers.16

St. Augustine uses this image, interestingly, when he refers to Jerusalem. The church always fought pilgrimages to Jerusalem, because it was a vote of no confidence for Rome. There must be more than one center in the world, Augustine argued. Just as a fire sends forth sparks, and each new spark lands somewhere and starts a new fire, so did Jerusalem. Despite the fact that there were many centers, they were all the one. There is no need to be disturbed by the existence of multiple centers. Compared with it all, the worlds are but as a shadow, since it is the Spark whose light moves all material things.17

The Latin word fundamentum refers to the lump of butter in the cream you are churning.18 At first there is nothing hard, nothing firm. There’s matter out there, but it’s very thin.19 So the frog starts to churn, starts to work at it, and in time a lump forms, quite mysteriously—as anyone knows who has ever churned butter. This text reads, “The fundamentum of the world begins to take form when it is touched by a scintilla; the spark ceases and the fountain is stopped when the inhabitants transgress.”20 We find this in the vision of Zenez (Kenaz), a record discovered long after Joseph Smith wrote about a Zenos in the Book of Mormon.21

“Matter without light is inert and helpless,” says the Pistis Sophia.22 “It is the first light which reproduces the pattern of the heavenly model, wherever it touches”;23“when the rays from the worlds of light stream down to the earthly world, for awakening mortals.”24 Sometimes the column of light joins heaven to earth,” as in our Facsimile No. 2 (a very important principle), even as the divine plan is communicated to distant worlds by a spark. According to Carl Schmidt, it is the dynamics of light from one world that animates another.25 “God’s assistants, the faithful servants of Melchizedek, rescue and preserve the light particles, lest any be lost in space.”26 The spark is also called “the drop”; the Egyptians call it the prt (“drop”). It is the divine drop of light that man brought forth with him from above, the spark that reactivates bodies that have become inert by the loss of former light.27 It’s like a tiny bit of God himself. Christ calls upon the Father to send light to the apostles.

It is the ultimate particle, the ennas, which came from the Father, of those who are without beginning, emanating from the treasure house of light from which all life and power is ultimately derived. Thanks to the vivifying and organizing power of the Spark, we find throughout the cosmos an infinity of dwelling places, other worlds, kosmoi (topoi is the word always used—the “places”), either occupied or awaiting tenants. These are colonized by migrants from previously established topoi or worlds, all going back ultimately to a single original center.28

The colonizing process is called “planting,” and those spirits which bring their treasures to a new world are called “plants,” more rarely “seeds,” of their father, or “planters” in another world. For every planting goes out from a Treasure House, either as the essential material elements or as the colonizers themselves, who come from a sort of mustering-area called the “Treasure-House of Souls.” (These early Christians had quite a system.29)

With its “planting” completed, a new world is in business. A new treasury has been established from which new sparks may go forth in all directions to start the process anew in ever new spaces; God wants every man to “plant a planting,” nay, he has promised that those who keep his law may also become creators of worlds. Thus you can say there is indeed but one God who fills the immensity of space, yet we are in the act too, as potential creators of worlds.

The idea of the universal center of the race is found throughout the ancient world. It’s the scene of great events.30

At hundreds of holy shrines, each believed to mark the exact center of the universe and represented as the point at which the four corners of the earth converged [the middle omphalos]—”the navel of the earth” [the umbilicus]—one might have seen assembled at the New Year—the moment of creation, the beginning and ending of time—vast concourses of people, each thought to represent the entire human race in the place of all its ancestors and gods.31

Time and place are always coordinated. After all, if you are going to have a universal meeting of people scattered all over the realm, what do you do? You appoint a particular place for them to come to. But if they are to assemble, they must come at a particular time, in a face-to-face meeting. That’s the function of the great assembly at the New Year, the best time, because there’s no planting or reaping going on. But most dramatically, it’s when the sun reaches its lowest point and must be renewed. And we must all participate in the revival of a new year, and a new age, in bringing things to life again, and make our new oaths and covenants for a new time.

A visitor to any of these festivals would have found a market or fair in progress, the natural outcome of bringing people together from wide areas in large numbers, and the temple of the place functioning as an exchange or bank. He could have witnessed ritual contests: foot, horse, and wagon races, odd kinds of wrestling.”32

The Icelandic colony in Spanish Fork, Utah, used to celebrate Icelandic Day in that fashion, at which there was ritual wrestling. It was a type of belt wrestling that is beautifully depicted in some ancient pictures from Egypt. At such festivals there was a Troy Game, beauty contests to choose the queen, etc.33 “All came to the celebration as pilgrims, often traversing immense distances over prehistoric sacred roads.”34

During this time, the King’s Highway was sacred, and to break the peace there was a capital offense. On that free and open passage, the king’s peace prevailed, for anyone who wanted to come to the king’s presence for any purpose. And during the festival, they naturally dwelt “in booths of green boughs,” to protect them from both the heat of the sun and from showers.35 They can have no houses: it’s not a place where the living dwell. When you leave it, as we learn in Exodus and again in Leviticus, you must eat the Passover with your staff in your hand and your shoes on your feet; and there must not be any of the food left by morning. Then you must hasten away and not look back (Exodus 12:11). It’s a holy place, and when the sun rises, the holy time is over. You no longer belong there. It’s maktos, the place of the spirits, because you had been there with the spirits and others.

“What would most command a visitor’s attention to the great assembly would be the main event, the now famous ritual year-drama for the glorification of the king. In most versions of the year-drama, the king wages combat with his dark adversary of the underworld, emerging victorious after a temporary defeat from his duel with death.”36 This is beautifully set forth in the first chapter of the book of Moses. Moses is proclaimed king after he has overcome many waters of Meribah—death; therefore, God says, “I shall make you king in my place, and you shall rule over my people as if you were God.” Moses is put in God’s place. “Blessed art thou, Moses, because thou hast overcome” (cf. Exodus 7:1; Moses 1:25-26).

So it was with the devil—up and down, up and down. Satan got Moses down, but in his last breath, Moses appealed to God and was rescued. When he saw the bitterness of hell, then it was that he went down (Moses 1:12-22). But he was rescued and became the victor and it was declared, “He shall rule my people and be to them as if he were God. And they shall follow him.”

Everything comes together at a particular time and place, at the center of the universe. “The New Year was the birthday of the human race and its rites dramatized the creation of the world; all who would be found in the ‘Book of Life opened at the creation of the World’ must necessarily attend.”37 You have always had the incisi in Rome, or among our ancestors you had to have your herör, and if you were touched by the king’s arrow, you had to come to the king’s presence; anyone who didn’t come to the New Year’s celebration within three days—whether at Swansea, or at Lund, or at the great Thing in Iceland, or in a hundred different places in England—would be banished from the kingdom for three years. You were considered to be in a state of rebellion, because you didn’t come to acclaim the king. You refused to give him your voice, your acclaim.38 This was all very important. In Rome, during the time of the Republic, you had to come with your family from great distances, even from Sicily, so they could be registered again and receive the annona,39 the yearly gift, a guarantee of prosperity for the new year. If you didn’t come, your name would be struck from the list of the incisi, the huge lead tablets that swung on great, wooden poles in the temple in the capital. If your name was not on that, you were hosticus, an outlaw of the state.

That’s where the word outlaw comes from. If you did not come to the king’s presence when he summoned you, you were outside of the law, because you would not acknowledge the law. That was the case with Cain, who was thrown out.

So if you are not there, and are not found in the Book of Life, which is

opened at the creation of the World. . . . There were coronation and royal marriage rites, accompanied by a ritual representing the sowing or begetting of the human race; and the whole celebration wound up in a mighty feast in which the king as lord of abundance gave earnest of his capacity to supply his children with all the good things of the earth. The stuff for the feast was supplied by the feasters themselves, for no one came “to worship the king” without bringing his tithes and firstfruits.40

No one comes to the presence of the king empty-handed. So here they are, all coming together.

And the omphalos is a three-dimensional center, the origin of the “hierocentric idea,” coined by Eric Burrows,41 the Assyriologist who pointed out in such writings as the poem Enuma Elish what happened on the new year when all the people came together. Enuma elish means “as once above,” “as it once happened above,”42 in the beginning at the creation, when the Lord of life was challenged by the powers of darkness; and in order for the trinity to combat it, the Father begat Marduk in his own image. First Marduk slew the monster Tiamat and made the material world out of its body.43 Tiamat was the great matriarch who plotted to put her son Kingu (who is Satan) on the throne.44 They were overcome and cast out. Then Marduk placed part of the material above, part below. Between these three levels he placed a barrier—a bolt.45 “Then he went the rounds of the heavens (“around them”) and inspected the various holy places, in order to establish there an exact replica of the Apsu, the dwelling of Ea.46 So the Apsu (the abyss) is what is above, and what is below. Ea is water; the Sumerian word for temple is Esagil (Babylonian: Esagila), which is over the waters of the underworld. The idea is that he traced an exact replica of each world on the other (the Egyptian rule of three, which Gardiner tells us about). Whatever happens in this world happens above and happens below. The three levels are related.

Then the Great Lord measured the dimensions of the Apsu and established his own dwelling, his image, Esarra, which shall be his temple on this earth—as Ea is below, and the Apsu is above.47 On this earth is the Esagil (the great palace at Babylon), which has the same dimensions as the Apsu—and Anu, Enlil, and Ea (the great trinity) then occupy their dwellings.48

The Anunnaki, the spirit children who come down to earth, built the great temple of Esagil, a replica of the great abyss, the temple at the Apsu. They represented it by the ziggurat, which is over the Apsu.49

Now Enlil, Ea, and Marduk founded his dwelling, his house. After that, the Anunnaki traced for themselves their sanctuaries upon the earth at Esagil, the great temple, which is the vault of the Apsu—the dome—at which point they would come together and unite themselves. There they received their order from gods.50

This is the Babylonian hymn of the creation. The king of Babylon had to disappear each year, in order to show that he could overcome death. He would disappear in an underground vault, where he would be humiliated. A priest would slap his face until the tears ran down; he would be clothed in a mock robe and crowned with a crown of weeds. A reed would be put in his hand. Then the lord of misrule, the false king, took his place for three days.51

At the end of three days, the king emerged from the tomb triumphant to show that he had overcome death and to rule for a new year. As he came forth, a great hymn, the Enuma Elish, was intoned by all the people. In other words, they were repeating what had happened elsewhere, before—the pattern on which this particular earth was founded: “This is Babylon, the place upon this earth where you shall dwell.”52 (The same thing happened at the beginning of Egypt, much earlier.) The Enuma Elish was written about 1700 B.C., though the rites were much earlier.53

“Come here and rejoice in this play, and celebrate his feastival.”54 That sounds exactly like Deuteronomy. “They served the Zarbabu and inaugurated the festival. In the Esagil . . . all the laws were fixed, and all the destinies were determined.”55 The king would go up to the top of the ziggurat (of seven levels), to a round table which represented four possibilities.

He would cast the dice, which bore 36 possibilities, to find out what would happen each day of the year—to determine the destinies of the year, according to which quarter of the table the dice landed on.

The stations of the heavens and the earth were fixed at this place. [All time and space shall meet here.] The laws were fixed here. [Everything is determined here.] And his fathers exalted the work which he had done [and celebrated God].56

Let the son be exalted, . . . may his power be almighty, may he impose his yoke upon his enemies. Let him exercise his pastorate upon the black heads [which is what they called themselves: the true people]. Let them come to this place under his protection throughout the years. Let them repeat these rituals without ever forgetting any of his exploits [or any of his great deeds for them].57

In the Roman year rites, if there was anything non rite non recte parum solemnitatis that had not been done ritually correct, or without sufficient solemnity, the whole seven-day festival had to be run over again. It could be done as many as seven times over. Remarkably, you find the same pattern pervasively, and it’s very old.

“And let them here burn incense and receive guarantee of nourishment for the year.”58 The Arabic mathal could be translated as “a likeness” in the heavens of that which is done on the earth. What interests me now is how old this stuff is.

I spent eight months in England in 1943 and 1944 preparing for the invasion of Europe, at Grenham Lodge, not far from Avebury, near Marlborough, on the plains of England. This is one of the oldest (2600 B.C.) and largest monuments of Europe, 500 years older than Stonehenge. It’s enormous. Much excavating has been done there. On days off, I had a chance to inspect it, and I was electrified by it. I had a lot of guesses about what had happened there. Silbury Hill (Wiltshire), an artificial mound, was set up there in the place of the assembly, for the mountain of the law.

Excavations have revealed that originally it was a sevenfold tower, like the towers in Babylon, or like the original pyramids (step pyramids) of Egypt, rising in seven stages.59 The author of Prehistoric Avebury, Burl, is a very conservative scholar. He abhors anything sensational. So his conclusions are very interesting. At this same time “in other parts of the British Isles people were already putting up great stone circles for ceremonies. At Stennes in the Orkneys [in Scotland halfway to the North Pole ] twelve steepling columns stood in a ring”60—as Jacob did in Israel, whenever he made a covenant (Genesis 31:45-46).

Twelve steepling columns stood in a ring. . . . In Ireland the chambered round cairn of New Grange with its quartz walls with a passage aligned towards the midwinter sunrise was placed inside a circle of over thirty massive blocks of stone. In the Lake District, source of many stone axes, people were going to splendid stone circles with names that peal like a prehistoric role of honour: Long Meg and Her Daughters, the Carles at Castlerigg, Sunken Kirk, the Grey Horses. Rites inside these sacred rings differed but in every region where there was a fair-sized population circular enclosures where the foci [notice the focus, the center points] of ceremonies, megalithic rings in the north and west, henges of earth or chalk in the stoneless areas of lowland Britain.61

That’s how they differed in form but they always have the ring, and they always do the same thing when they come together. It is vastly older than the pyramids, is beautifully done, and contains magnificent things. These did not necessarily originate from the Near East, as once was thought. Ideas worked both ways.

The point is that our ancestors were doing all this far back in time. The Beaker people didn’t come until 2100 B.C. They were the ones that built Stonehenge, though they hooked into the existing traditions, while bringing their own. In the earliest times, everybody seemed to be doing the same sort of thing, building the same kinds of structures.

Burl is very fond of comparing these things with the “Hopewell Indians of the Ohio,” a good three thousand years after. Why should this be, he asks, that they should be doing the same thing?62

“Avebury became almost a metropolitan centre to which people came from miles around to trade and to settle disputes, to worship in the marvelous stone rings that expressed the barbaric pride of the natives.”63 And the remains are not a few. There are piles of stuff to show what was going on at these places. They were all doing the same sort of thing.

More to the point:

Death and regeneration are the themes of Avebury. The presence of human bones, the pieces of stone, the red ochre, the pockets of fertile earth, the antlers, the shapes of the sarsens, the architecture of the avenues and circles, all are consistent with the belief that Avebury was intended as a temple in which, at various times of the year, the large population could gather to watch and take part in ceremonies of magic and evocation that would safeguard their lives.64

Less than a year ago I received a report from the University of Chicago, in cooperation with a university in Spain, of an excavation of the most ancient of these foundations in the world, very accurately dated to about 13,920 B.C., give or take two hundred years.65 Fourteen thousand years ago is a long time; Avebury is only 2600 B.C. And would you believe it, excavators are finding the same stuff—the same combination of stuff way back then? You can’t get away from it. Primitive man was really up to something; he had a definite idea behind what he was doing.

Gordon Childe [the great Scottish prehistorian] thought of Avebury as a cathedral, Stuart Piggot as an open sanctuary associated with a sky-god, Isobel Smith as a monument dedicated to a fertility cult whose practices included the use of stone discs, balls of chalk and human bones. Jacquetta Hawkes wrote of fertility rites involving the earth and the sun although “what those mysteries were we shall never know.” However generalised these observations there is agreement about a religious centre for fertility cults linked with the earth, the sun [the heavenly bodies in their motions], ritual objects and dead bones [i.e., with the ancestors, and scholars all agree on that]. Not many years ago Patrick Crampton went further, suggesting that Avebury was not only a temple of the powerful Earth Goddess but also a “city,” the first “capital—religious, cultural, commercial—of most of southern Britain.”66

So these concepts were very old. I myself was enormously impressed by the size of the stones, weighing sixty tons, set in a great circle 350 yards across. It was an amazing accomplishment that they dragged them to the site. It required great work, concentration, and leadership. Burl says the population of all Western Europe couldn’t have been more than forty-eight thousand people at the time. But there must have been many more than that.67

The enormous ditch around the stones is thirty feet deep, dug out by use of only deer horns.68 For ritual reasons, they could not use anything else.

I used to fly over the area frequently. You could see radiating from the site great table stones, and the great prehistoric roads that led to the site, from hundreds of miles to the north. From everywhere, people came to Avebury, nearly five thousand years ago, to celebrate the very thing we do in our temples today—the continuity of life.

We do have from this same time the actual full pyramid texts, from the tomb of Unas, who ended his rule in 2524 B.C. The Egyptians did the same things when they met at the sacred points. The reading begins with the council in heaven, followed by a dramatization; from that to the creation of the world and the coming of man; then to the fall and the redemption—all accompanied by ordinances. At that time, only the king received them, but very soon after, the nobility also did, and eventually all the people. They received their washings and anointings, their names, and the whole initiation. As the end of the Shabako Stone says, “to become glorified, a king for eternal exaltation.”69 All were supposed to do that.

The temple as the center of the universe may be a myth, but it is the most powerful myth that ever possessed the human race. Mircea Eliade has written a book on that topic, Cosmos and History: The Myth of Eternal Return, in which he deplores the fact that contemporary man has completely cut that tradition off. He says,

The chief difference between the man of the archaic and traditional societies and the man of modern societies [with reference to the place he assumes in the cosmos] with their strong imprint of Judaeo-Christianity lies in the fact that the former feels himself indissolutely connected with the Cosmos and the cosmic rhythms, whereas the latter insists that he is connected only with History.70

We now live in a technological world; let us not worry about other problems. Technology will solve all those. The other stuff is outdated. But for thousands and thousands of years, our ancestors went through those things. So let us think about it all for five minutes.

Notes

1.

William Butler Yeats, “Second Coming,” stanza 1, lines 14-16; in Joseph Hone,

W.B. Yeats

(New York: Macmillan, 1943), 351.

2. James E. Talmage, The House of the Lord (Salt Lake City: Deseret, 1912), 178.

3. Giorgio de Santillana and Hertha von Dechend, Hamlet’s Mill (Boston: Gambit, 1969), 383-86, 306-7.

4. Cf. Hugh W. Nibley, “Tenting, Toll, and Taxing,” WPQ 19 (1966): 602; reprinted in CWHN 10:35; 74, n. 15.

5. Cf. Werner Müller, Die heilige Stadt: Roma quadrata, himmlisches Jerusalem und die Mythe vom Weltnabel (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 1961); and Werner Müller,Kreis und Kreuz: Untersuchungen zur sakralen Siedlung bei Italikern und Germanen (Berlin: Widukind, 1938).

6. Charlton T. Lewis, A Latin Dictionary (Oxford: Clarendon, 1969), 1831.

7. Mircea Eliade, Cosmos and History: The Myth of Eternal Return (New York: Princeton University Press, 1974), 12.

8. Cf. Nibley, “Tenting, Toll, and Taxing,” 603-4; in CWHN 10:41; 76, nn. 25-26.

9. Hugh W. Nibley, “The Hierocentric State,” WPQ 4 (1951): 226-53; reprinted in CWHN 10:99-147.

10. Mircea Eliade, Le Chamanisme et les techniques archaïques de l’extase (Paris: Librairie Payot, 1951); for translation, see Willard R. Trask, tr., Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstacy (New York: Pantheon, 1964).

11. Cf. Nibley, ” Tenting. Toll, and Taxing,” 604; in CWHN 10:41; 76-77, nn. 27-29.

12. Eliade, Le Chamanisme et les techniques archaïques de l’extase; for translation, see Trask, tr., Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstacy, 260-61.

13. Nibley, “Hierocentric State,” 226-53; in CWHN 10:99-147. Cf. Eric Uphill, “Egyptian Sed-Festival Rites,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 24 (1965): 365-83.

14. 1 Jeu 39, in Carl Schmidt, ed., The Books of Jeu and the Untitled Text in the Bruce Codex, tr. Violet MacDermot (Leiden: Brill, 1978), 88, lines 13-22.

15. Second Gnostic Work 2a-3s; 18a; see Untitled Text 1-3, in Schmidt, Books of Jeu and the Untitled Text, 226-30; cf. Hugh W. Nibley, “Treasures in the Heavens: Some Early Christian Insights into the Organizing of Worlds” DJMT 8 (Autumn/Winter 1973): 83; reprinted in CWHN 1:184.

16. Pistis Sophia I, 58, in Carl Schmidt, ed., Pistis Sophia (Leiden: Brill, 1978), 112, lines 4-25.

17. Untitled Text 2, in Schimdt, Books of Jeu and the Untitled Text, 227.

18. Cf. Lewis, Latin Dictionary, 792.

19. De Santillana and von Dechend, Hamlet’s Mill, 383; see the discussion on Amritamanthana.

20. The Vision of Kenaz, which appears in M. R. James, Apocrypha Anecdota, Texts and Studies, ed. J. A. Robinson, 10 vols. (Cambridge: Cambridge Universtiy Press, 1893), 2:3:179; cf. OTP 2:342.

21. James, Apocrypha Anecdota Texts and Studies, 174-77; cf. Hugh W. Nibley, Since Cumorah (Salt Lake City: Deseret, 1967), 322-27; reprinted in CWHN 7:286-90; cf. OTP 2:341-42.

22. Pistis Sophia I, 55, in Schmidt, Pistis Sophia, 107.

23. Text 146:14-16, in Alexander Böhlig and Pahor Labib, Die koptisch-gnostische Schrift ohne Titel aus Codex II von Nag Hammadi (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 1962), 39; cf. On the Origin of the World II, 98, 14-15, in NHLE, 162.

24. Ethel S. Drower, The Thousand and Twelve Questions (Berlin: Akademie, 1960), 99-100.

25. Carl Schmidt, Gnostiche Schriften in koptischer Sprache aus dem Codex Brucianus, in Texte und Untersuchungen 8/1-2 (Leipzig: Hinrichs, 1892), 331.

26. Pistis Sophia I, 25, in Schmidt, Pistis Sophia, 34-35.

27. Sophia Christi 104:4-6; 119:1.

28. Untitled Text 19-20, in Schmidt, Books of Jeu and the Untitled Text, 261-63.

29. Mark Lidzbarski, Das Johannesbuch der Mandäer (Giessen: Töpelmann 1915), 60, n. 6.; cf. CWHN 1:209, n. 98.

30. Nibley, “Hierocentric State,” 226-53; in CWHN 10:99-147.

31. Ibid., 226; in CWHN 10:99.

32. Ibid.

33. Ibid.

34. Ibid., 226; in CWHN 10:99-100.

35. Ibid., 226; in CWHN 10:100.

36. Ibid.

37. Ibid.

38. Hugh W. Nibley, “The Arrow, the Hunter, and the State,” WPQ 2/3 (September 1949): 330-31; reprinted in CWHN 10:4-5.

39. Cf. fig. 15 in CWHN 10:159.

40. Nibley, “Hierocentric State,” 226-27; in CWHN 10:99-101.

41. Eric Burrows, “Some Cosmological Patterns in Babylonian Religion,” The Labyrinth, ed. Samuel H. Hooke (London: SPCK, 1935), 46-48; Nibley, “Hierocentric State,” 226-27; in CWHN 10:99-101.

42. Enuma Elish I, 1.

43. Enuma Elish, IV, 133-40.

44. Enuma Elish, V, 146-55.

45. Enuma Elish, IV, 138-46.

46. Enuma Elish, IV, 138-42.

47. Enuma Elish, IV, 142-44.

48. Enuma Elish, IV, 145-46.

49. Enuma Elish, VI, 62-64.

50. Enuma Elish, VI, 68-70.

51. François Thureau-Dangin, Rituals Accadiens (Paris: Leroux, 1921).

52. Enuma Elish VI, 72.

53. Henri Frankfort, Kingship and the Gods (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971), 319.

54. Enuma Elish VI, 77-78.

55. Enuma Elish, VI, 77-78.

56. Enuma Elish VI, 85.

57. Enuma Elish, VI, 106-9.

58. Enuma Elish, VI, 112-13.

59. Aubrey Burl, Prehistoric Avebury (London: Yale University Press, 1979), 131; cf. Burrows, “Some Cosmological Patterns,” 68-69.

60. Burl, Prehistoric Avebury, 140.

61. Ibid.

62. Ibid.

63. Ibid.

64. Ibid., 200.

65. L. G. Freeman and J. González Echegaray, “El Juyo: A 14,000-Year-Old Sanctuary from Northern Spain,” History of Religions 21 (August 1981): 1-19.

66. Burl, Prehistoric Avebury, 202.

67. Ibid., 178.

68. Ibid., 175-76.

69. Cf. Shabako Stone, line 64, in Miriam Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature, 3 vols. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1943), 1:56.

70. Eliade, Cosmos and History, xiii-iv; cf. de Santillana and von Dechend, Hamlet’s Mill.

0 notes