#and in fiction we also have like. accumulated symbolism and patterns

Note

Your Thor metas are interesting. I agree that the neck-touching is very unusual and seems to carry abuse imagery throughout Loki's entire arc (and it's how Loki died by Thanos). I have siblings and I don't think I've ever touched their necks. I am not sure if you like being perceived, so let me know if not.

hi! thank you :D i don't mind being perceived - the reason i post in my own tag rather than the main ones is because there was a stage when i was making 30 or more posts a day and i didn't want to either a) get discoursed or b) get banned. comments questions criticism etc are all welcome :)

and yes, i don't think i've ever done that to my siblings either. but, then again, i've also never used "brother/sister" as a serious form of address. i'd say that, as a non-aggressive gesture of affection, it seems to be a lot more normal within an asgardian cultural context. we see it in a few other relationships:

thor to sif in T1. thor persuades sif to leave the battlefield when it becomes clear she can't win. thor is quite forceful here too - he fully turns her around to look at him, and he's clearly giving her orders - but there's no anger or threat in it.

thor to jane in TDW. they argue - jane actually hits him - and then thor puts his hand on her jaw/neck to tell her "fate has brought us together". thor is trying to get her back on his side, and to cover up his own nerves. (the latter doesn't entirely work.)

odin to frigga in TDW. this is just a gesture, no real tension, but it is a little possessive - he calls her "MY queen" at the same time - and authoritative - he's trying to dismiss her fears for him.

thor to bruce in T3, i think? i can't remember the specifics of this one, but at some point, thor uses it to try to keep bruce calm so he can stay in his human form.

which gives us an interesting bundle of connotations, even before we get to how it mingles with violence for thor and loki specifically.

it's a medium-intimate gesture (friends, family, fellow warriors, etc) that's meant to project an air of invulnerable authority, calm down the recipient, and impose order and social cohesion (which is sometimes a synonym for obedience.)

there are two couples on the list, but even disregarding loki and bruce, the presence of sif makes me pretty confident asgardians don't view it as romantic by default (the way some viewers seem to), since thor not having feelings for sif is A Whole Thing.

HOWEVER. i do think it's subtly gendered - we always see it done by a normative/ideal man to someone with less social power - a woman, or an "overemotional" man, or someone who acts outside their gender role (loki + sif)... etc. (not saying that's a hard rule, to be clear. just an interesting pattern.)

(and it's also relevant that the three recipients of this gesture in TDW - frigga, jane, and loki - all either die a sacrificial death or, in jane's case, very narrowly escape one. TDW treats (self-)sacrifice as a form of subjugation.)

[it's also interesting that there is, as far as i'm aware, precisely one reversal, where the gesture goes up the power dynamic instead of down (loki to thor), and it's in a *deleted scene* in T1. i know a lot of people like to take deleted scenes as canon, and sometimes i do too... but i also like to consider the fact that they ARE, deliberately, deleted. they could've shown us a break in this pattern, but they never did.

(i mean, this certainly won't be the main reason for deleting that scene, given that the motif was solidified in the avengers, but still... it could be a factor. and regardless of intent, the pattern is interesting.)]

[edit: i misremembered the deleted scene! it's STILL thor to loki in that one. so we have NO reversal at all...]

so ummm yeah! overall... in this story, it's not always overtly aggressive to touch someone's neck, but it IS generally pretty hierarchical. and it is pretty normal in asgardian culture... but of course, they're an absolute monarchy. a lot of bad things are "normal" to them lol.

#space viking tag#god this got long. sorry. head full of bees#and idk in case it isn't clear for anyone reading this:#of course *in a vacuum* the neck is just a body part and there's no particular reason why touching it should mean... anything#but we have cultural expectations/norms#and in fiction we also have like. accumulated symbolism and patterns#so. in thor *specifically*. it's Ominous.#meta#ch: thor#ch: loki#r: loki + thor#th: neck touch#th: gender + sexuality#th: servant prince

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Realistic phoneme inventories 1: Vowels

All of the old webpages that I used to rely on for at-a-glance information about vowel systems when designing new phoneme inventories for my conlangs seem to have succumbed to various forms of link rot; and I’ve never found a good overview of how to build consonant inventories in a systematic way. So I want to set out, for my own reference and for others, an overview of both vowel and consonant systems as they tend to exist in natural languages, with an eye to creating conlangs with natural-feeling distributions of sounds.

A phoneme inventory is, of course, only one of the most basic elements of a conlang. I won’t be dealing with phonotactics, with suprasegmental features like tones, and certainly not with grammar or syntax or anything like that. A good starting point for lots of those topics is the LCK, either online or in print.

Also, phonology is not my strong suit; I’m more of a morphology person by inclination, and all my knowledge of linguistics comes essentially from years spent conlanging as a hobby. So apologies in advance if I get any terminology messed up. My primary references for this post specifically are this paper on vowel systems, this paper on consonant systems, the relevant chapters from the WALS, and conlanging resources like the LCK.

For length reasons, I’ve broken this post into multiple parts. Part 1 will deal with vowels; part 2 will deal with consonants.

1. Background information

You could, when creating a conlang, select sound arbitrarily based on what sounds pleasing to your ear, what you can easily pronounce, your favorite natural language, or your favorite IPA symbols. For conlanging as a purely artistic enterprise, those are all perfectly fine criteria; but if you want your conlang to reflect trends in natural languages--perhaps as for conlangs which are the putative natural languages of science fiction and fantasy settings--it’s helpful to understand why humans make the noises they do with their faces, and how.

The human vocal tract is a resonant column of air, stretching from the vocal cords to the lips (and nostrils, for nasal sounds), not unlike the pipe of a pipe organ, or the body of a flute. Air expelled from the lungs moves through the vocal tract and, thanks to our well-developed throat, mouth, and facial muscles, and the elaborate control over them provided by a region of the brain called Broca’s Area, we can rapidly reshape our vocal tract and manipulate the resonances of the air passing through it, producing speech.

In principle, we could make an almost infinite number of subtly different motions with our various speech-producing organs to produce an equally limitless quantity of different sounds. In practice, however, speech has to be an effective way of encoding information, or it’s useless as a communication tool. Therefore, we want sounds to be as different from one another as possible, as distinct to the ear as they can be, so they can be clearly distinguished from one another, and clearly heard over noises like wind and crackling fires and loud music. And because we talk constantly, we want speech to be as easy as possible; we are going to tend to restrict ourselves to the easiest sounds for the human vocal tract to produce.

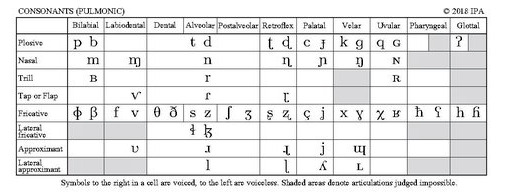

So the IPA, the system for transcribing human speech sounds, only has about 107 basic symbols for consonants and vowels.

The IPA consonant chart. Shaded areas are “articulations judged impossible.” White areas with no symbol are sounds that aren’t impossible, but which aren’t widely attested in the world’s languages to need a specific transcription.

Of all the sounds covered by the IPA which actually show up in natural languages, only a small subset are truly common. Some, like the plosives /p t k/, are nearly universal. In general, the easier to produce (and more acoustically distinct) a sound, the more common it is; and languages will tend to make use of commoner sounds first (like plain plosives) as their phoneme inventory grows, before they have recourse to less common sounds (like pharyngealized plosives).[1]

The other important thing to note about phonemes is that they’re not atomic. The human brain is an extremely powerful pattern-recognition machine, and whether we’re learning our L1 as babies or learning our sixth L2 as an adult, we break languages down into many different patterns and systems as we learn them. It’s easier to learn, for instance, the general pattern that “third-person present verbs in English end in -s” than to learn, as separate pieces of information, “okay, after ‘he, she, it’ the verb ‘put’ is ‘puts’ and the verb ‘see’ is ‘sees’ and the verb ‘run’ is ‘runs’...” etc.[2] But we usually do not learn these patterns explicitly, and even when sitting down in a classroom to learn a language, there’s only so much use you can get out of memorizing a table of conjugations or declensions--it’s hard to speak fluently if you have to pause in a conversation to go, “hmm, okay, but what’s the dative femine form of the article?” Most language learning requires acquiring an intuitive grasp of the patterns of language; and you only acquire that intuition through lots of speaking and listening.

A consequence of our dependence on intuitive understanding is that two people’s intuition can differ. For instance, many people learn the rule in English that “I” is nominative, and “me” is objective; and so, unless the first person pronoun is the object of a verb or preposition, you must use “I”: “Gowron is better at Klingon politics than I.” Sometimes, this is analyzed as having an implied verb: “Gowron is better at Klingon politics than I [am].” But over the centuries of people speaking English, many people internalized a different rule. Because pronouns crop up as the objects of verbs or prepositions more than as the subjects of verbs, the objective forms came to be reanalyzed as the default forms. The nominative form became a special, marked form--one that only occured in certain cases, which was, over time, simplified into “only when the subject of a verb.” Therefore, for these speakers of English (me included), the rule became: “when appearing to the left of a verb, use ‘I’; otherwise, use ‘me.’”

Out of the steady accumulation of such petty reanalyses, great changes in grammar are born.

The same process is at work in the sounds of a language. Just like grammar, sound is heavily systematized, and encapsulated by the brain as a set of patterns. Only instead of cases or persons or numbers, the component features of sounds on which patterns are based are called their “features.” And, as with any good Saussurian principle of sign-distinction,[3] we only care about a minimal set of features which, as a community of language-speakers, we all agree are the relevant ones for distinguishing sounds. For instance, if our language has the consonant sounds /p t k b d g m n/ (the unvoiced and voiced plosives, and some unvoiced fricatives), we might need only the feature [voiced] and [nasal] to distinguish the sounds of our language. But, because we learn these rules implicitly, and we don’t have to give our youngsters a background in up-do-date phonetics research before they can say “papa”, maybe later generations of speakers, or the next village over, notices a different set of features. After all, we have to physically produce these sounds with our mouth; they don’t exist in a perfectly idealized acoustic realm. Some speakers of our language may come to see the defining feature of the voiced stops as only [+voiced], and since there are no fricatives which they can be confused with, start pronouncing them with a less constricted airflow to make them sound even more distinct from the unvoiced stops. So gradually /b d g/ become /v ð ɣ/, the voiced fricatives produced at the same place in the mouth. As far as the speakers of the language are concerned, the sounds haven’t changed--[+fricative] is not a phonemic feature of their language! The pattern isn’t changed, at least not yet. But more sound changes will accrete over time, and they may affect the new series of fricatives differently than they do the stops; and with a few more changes like this, soon you may have a version of the language that sounds completely different and is entirely mutually unintelligible.

Sound changes are 1) regular, and 2) have no memory. While sound changes can be triggered only by certain phonetic environments (say, the voicing of /p/ to /b/ between two vowels), if the conditions for a sound change are met, it will be triggered everywhere it applies.[4] And later speakers of the language won’t remember that /v ð ɣ/ used to exist in opposition to /p t k/ (unless they take a class in historical linguistics); they’ll treat these sounds on their own terms.

When the exact production of a sound varies within a language, usually altered by context due to the physiological considerations surrounding making that particular face-noise, this phenomenon is called allophony. Different versions of the same underlying sound are allophones. The sound as a unit of the formalized pattern stored in your brain is a phoneme. A phonemic transcription (between slashes /like this/) is a transcription of a sound or sounds as these abstract phonemes. A phonetic transcription (between brackets [like this]) is a transcription of a sound or sounds as something like their actual acoustic realization.

2. The vowel space and vowel planes

Consonants involve obstructing or redirecting the flow of air through the vocal tract, often entirely (as with plosives), or turbulently (as with fricatives). Combined with the large number of distinct places of articulation, involving the teeth and tongue and palate, consonants can all sound very distinct from one another. As a consequence, small consonant inventories can restrict themselves to a small subset of the full space of possible consonants, and still be fairly distinct from one another. In fact, in languages like Hawaiian or Rotokas, with very small consonant inventories ( /m n p t~k ʔ h w~v l~ɾ/ for Hawaiian and only /p t k b~β d~ɾ g~ɣ/ for Central Rotokas; the ~ symbol indicates allophonic variation between two sounds, depending on speaker or context), it’s very unlikely there’s going to be any sound that’s really difficult for a speaker of a language with a more complicated consonant inventory like English to pronounce.[5]

Vowels, though, don’t involve specific points of contact between different parts of the vocal tract in the same way as consonants; vowels are produced by the relative position of the tongue in the mouth, with an unimpeded air flow and the vocal cords engaged. This means that vowels can vary subtly--and, as a consequence, that languages tend to spread the vowels they have out, throughout the entire articulatory and acoustic space available to them, in a way they don’t have to do with consonants.

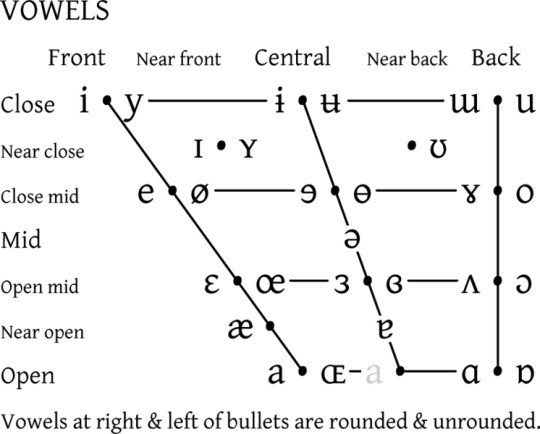

Here’s the IPA vowel chart:

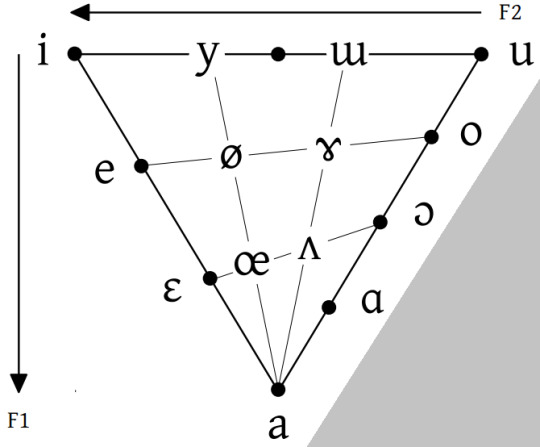

The reason it’s longer at the top and on the left side is because there is more acoustic differentiation possible when the mouth is more closed versus more open, and when the tongue is more front than back. Languages will especially tend to have more close (or “high”) vowels than open (“low”) vowels. That’s not the only property that affects how vowels tend to be distributed though. Here’s a schematized diagram of the vowel space based on the actual acoustic components of the vowels:

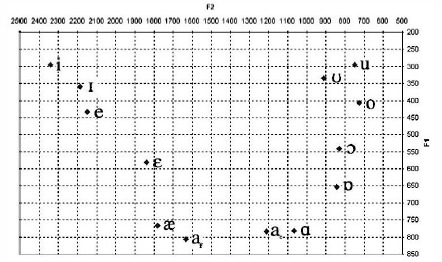

Speech sounds are composed of different-frequency elements called “formants;” the lowest-pitch formant is F1, the next-lowest F2, and so forth. For most vowels most of the time, F1 and F2 are the really important formants. Open vowels have higher first formants, and close vowels lower first formants; front vowels have higher second formants, and back vowels have higher low formants. Here’s a similar chart, showing actual values, from the Hitch paper:

But we don’t recognize vowels just using their pitch. If it did, we could in theory have languages with hundreds of vowels: the ear and brain together can detect extremely subtle gradations of tone. Rather, what matters more is the relative value of vowels, the distinctive features like [+front] or [-high].

Most languages have small vowel inventories; in terms of the psychological perception of vowels, the vowel space is quite small. WALS classified any language with 4 or fewer values as “small,” languages with 5-7 vowels as “average,” and any language with more than 7 as having a “large” vowel inventory. Germanic languages like English, which have anywhere from 10 to 17 (!) vowels, are monstrously bloated by global standards. Usually for larger vowel inventories, additional features will be added besides the spatial features so that vowels don’t have to compete for space: Latin doubles its vowel inventory (/a e i o u a: e: i: o: u:/) by adding a length feature, and Turkish (/i y ɯ u ɛ œ a o/) accomplishes something similar with rounding.

Additional sets of distinctions like these, which are not spatial distinctions, create different vowel planes, where vowels do not have to compete for space with one another directly. Vowel planes may be parallel (as in Latin or Turkish), or not. There may be phonological or grammatical processes that trigger vowels moving from one vowel plane to another, as languages with vowel harmony, where vowels in a word must share a particular feature like frontness or roundedness, or vowel planes may simply exist to provide additional acoustic contrast within a language’s vowel inventory.

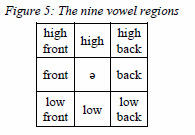

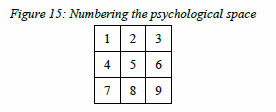

Traditionally, languages with large vowel inventories have been analyzed as having many degrees of front/back or height distinction: four, in languages like Danish, or even sometimes five, as in the case of one Bavarian dialect Hitch cites in his paper. However, Hitch argues that the psychological space available for the vowel plane is really divided by reference to a perceived “neutral” vowel, one that may not be phonemic in a language, but will still crop up in paralinguistic utterances (like English “ugh” or “uh-huh”). It is by comparison to this vowel that vowels acquire distinctive spatial features, and as such, there are really only nine ways, at most, to divy up the vowel plane:

No language, in Hitch’s analysis, really has more than three distinctions of height or backness. When you think you have more, as in Danish, it’s time to take a look at the possibility that some apparently spatial feature really reflects an underlying contrast that isn’t spatial. Remember, it’s only the phonemic features of a sound that are fixed: the non-phonemic features can vary, sometimes by quite a lot.[6] Anything higher and fronter than the neutral vowel will count as a “high front” vowel, and its exact spatial realization may not be the same in each vowel plane.

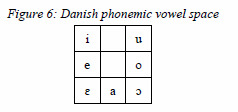

Danish, for instance, has the vowel inventory /i e ɛ a y ø oe u o ɔ/ and is analyzed as Hitch as having the primary vowel plane

The three front rounded vowels /y ø oe/ form a distinct plane, one in which the only distinctive feature is height: high round, mid round, low round. The “frontness” of these vowels is a phonetic feature, but not an important phonemic feature. They don’t contrast directly with the rounded back vowels, because back vowels are usually rounded--it makes them more acoustically distinct from mid vowels, and round back vowels show up in tons of languages, like Latin, that don’t make a phonemic contrast for rounding. And rounding has a side effect on front vowels, making them sound a more central: thus, the “front round plane” is, perceptually speaking, more of a mid round plane distinguished by the [+round] feature. Languages can have multiple secondary planes. According to Hitch, Jalapa Mazatec “may have six parallel planes.”

Vowel harmony doesn’t have to operate across planes: Hitch provides the example of the three-vowel language Jingulu, which as /a i u/. A suffix in /u/ or /i/ will raise the preceding vowel unless a high vowel intervenes: bardarda, “younger brother” + -rni > birdirdirni, “younger sister.” But if often does, with apparent height distinctions being better understood as plane distinctions: “In these languages, the vowels in a particular word will all be from one plane or the other. It seems that the choice of plane is determined at the lexical level. In the lexicon, the words contain archiphonemes spanning both planes, and each word is marked with a feature indicating plane membership.”[8] Even if a language doesn’t have clearly non-spatial articulatory features distinguishing its planes like nasalization or length, it can still have two vowel planes that exist side by side. For Ogbia, a language of Nigeria, Hitch gives two vowel planes corresponding to one with the advance tongue root feature (+ATR) /i e u o ɐ/ and one without (-ATR) /ɪ ʊ ɛ ɔ a/. For Nez Perce, five surface vowels /i u o æ ɑ/ correspond to two planes /i u æ/ and /i o ɑ/; a word can have vowels from one plane in it, but not both. /i/ happens to exist in both planes (possibly due to a merger of two distinct underlying vowels).

3. Vowel systems

So for any vowel system on a single plane, we’re going to have a maximum of nine vowels. Secondary systems may be the same size as the primary vowel plane; or they may be smaller. Either way, our vowel systems will tend to have one of two shapes, triangular or rectangular. In a triangular vowel system, acoustic considerations are dominant. We will have fewer open vowels, and more close vowels. In a rectangular vowel system, the psychological considerations are instead dominant, and vowels will be distributed in the nine-vowel grid in a more symmetric fashion.

These nine potential positions or “archiphonemes” don’t always reflect the same division of the vowel space given on the IPA. 7 and 9, for instance, might be open-mid vowels rather than true open vowels. 2 might be a rounded front close vowel. 5 may or may not be a schwa. 8, the bottom of the IPA trapezoid or the idealized acoustic triangle, is usually [a], despite [a] being, tecnically, a front vowel! I will simply quote Hitch at length here:

With those caveats, we can then look at the possible arrangements of vowel systems, from zero vowels to nine.

Zero vowels. “A zero-vowel language would insert vowels according to rules of epenthesis, then colour the vowels according to phonetic context. It sounds theoretically possible, but no completely convincing cases have yet been identified.”

One vowel. “There would seem to be no indisputable examples of one-vowel systems on a primary plane.” But there are languages with one-vowel secondary planes. If a language has one long vowel, for instance, it will be /a:/. But if a language has one nasalized vowel, it can be just about anything.

Two vowels. This includes languages with a two-vowel front round plane; also, languages with a primary plane that has just a height distinction. All Northwest Caucasian languages have /ə a/ (but feature lots of allophones). Most examples Hitch cites for two-vowel systems have some kind of central vowel (/ə/ or /ɨ/) plus /a/; but Witchita has /i a/. “But this type reveals something fundamental about vowels: that [low] is the most basic of the four spatial features.”

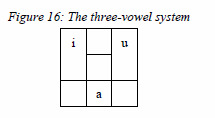

Three Vowels. The triangular system /i u a/ is a very common system among the world’s languages, with /i/ and /u/ having lots of vertical freedom.

Hitch is very down on the idea of a three-vowel on the primary plane; of the potential examples he cites, none are undisputed. But “Parisian French has a vertical three-vowel configuration /y ø oe/ on a front-rounded plane (primary /i u e ə o ɛ a ɔ/). While vertical three-vowel systems may not exist, primary plane triangular three-vowel systems are exceedingly common.”

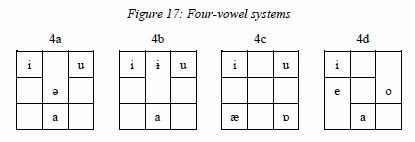

Four vowels. The triangular 4-vowel systems (4a and 4b) add a neutral vowel to the classic 3-vowel system. A straightforward rectangular system is possible (4c); as well as a slightly more complicated variation with more room for allophony (4d).

He also gives the unusual example of the Lummi dialect of North Straits Salish, which “appears to have no low vowels” /i e ə o/, though this is clearly an outlier.

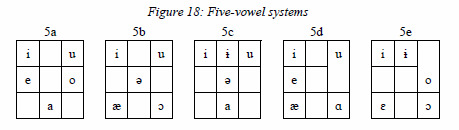

Five vowels. The Latin vowel system (5a) is an extremely common triangular system; a rectangular 5-vowel system is also pretty common (5b). Three other five-vowel systems are given that are “relatively rare,” being a triangular system that combines 4a and 4b (5c), a 4c-like rectangular system with a mid front vowel added (5d), which is “asymmetrical, because the acoustic space is dominant,” and a different variation on 4c that instead adds a high central vowel. As an unusual exception, Hitch notes that Tohono O’odham “appears not to fit the pattern of any other language, and to violate a universal by having more back than front vowels with /i ɨ u o a/.”

Six vowels. Adding a central mid or central high vowel to 5a gives two common triangular six-vowel systems (6a and 6b). A rectangular six-vowel system, with no central vowels, is also possible.

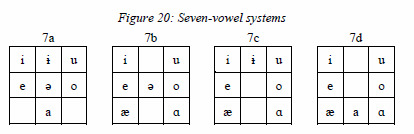

Seven vowels. There is one possible triangular configuration, 7a, with one low vowel. Otherwise, 7-vowel systems are rectangular systems that differ only on where they place the central vowel.

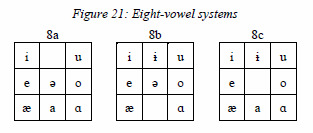

Eight vowels. Similarly restricted: there are only three possible configurations of eight vowel systems, depending on which central vowel is omitted. None appear to be very common, however.

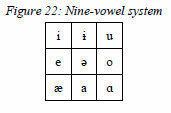

Nine vowels. Nine is the maximum number of vowels on a single plane, and therefore there is only one nine-vowel configuration possible. All analyses of more than nine “basic” vowels means you should start examining the possibility of multiple vowel planes.

In the next post, we’ll take a look at consonant systems.

Footnotes:

[1] https://wals.info/chapter/1 (ctrl+f “size principle”)

[2] Languages do have irregularities, where historic patterns have been obscured by sound change or other processes. But there’s a reason irregularities or fossilized forms tend to occur in commonly-used words and phrases rather than rarely used ones: it is harder to remember variant patterns for rarely used words, and so they tend to become regular by analogy.

[3] Cf. Ferdinand de Saussure, Course in General Linguistics. This is one of those texts that was mind-blowing to me when we read it in our Critical Theory course in undergrad, but now seems so obvious as to not be worth discussing. The key insight can be summed up very succinctly, though: human brains care about differences between symbols, not their absolute values. When it comes to the kind of meaningful differentiation required for communication, it’s the relative differences between signs that matter--so any sign-system can be simplified to the minimum required number of distinctions, without the loss of information or without impeding communication. This insight is relevant to everything from linguistics to information theory.

[4] Apparently irregular sound changes--why does the Early Modern English sound spelled <gh> get pronounced as /f/ in “enough,” but is silent in “through”?--are usually the result of patterns being obscured by analogy or borrowing. In this case, it’s because the prestige dialect of English that coalesced around London in the Early Modern period, and was influenced by speakers of English from all over England, sometimes borrowed words from other dialects that had undergone different sound changes. In some of those dialects, the <gh>-sound was lost. In others, it changed to /f/.

[5] The only sounds in either Rotokas or Hawaiian given above that don’t crop up as a phoneme or allophone in English are probably [β ɣ]. The former is just [v] pronounced with only the lips; the latter, the voiced equivalent of German or Scottish [x].

[6] For instance, the Middle English long vowels /iː eː ɛː aː ɔː oː uː/, had as their distinctive feature their length, not the exact contour of their sound. That meant that these long vowels could “break,” becoming diphthongs, but as long as they remained mostly distinct from one another, no confusion resulted. That breaking, plus the general reorganization of the vowel system that changed the pitch of the pure long vowels (the high ones, which could not acquire a high offglide because there was no space above them acoustically) later yielded the corresponding modern long vowels /aɪ i: i: eɪ aʊ u: oʊ/

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wandering Radical

Perhaps at the end of the day I am the sun, am as absurd as calling

It a morning sun or setting, like a battle between mind and mind,

To scope the angles of the clouds and sweetly

To assume the when, sans context

Of the time, completely blind to when, the sky in either case a mirror

Image. Its qualities indicate both ends of today,

Revealing the same hued leveling frames congealing on the horizon

Like wet sugar at the bottom of your cup of tea, which I am

Not sure this is; or I am

The sun’s ill-researched absurdity

Itself, whose heat spills all serious upon

The blank heavens: a blank dark as had ruled

Across the garden grounds where-

-The radical will, is fated to, wander. It is when

Our watches tell us that the day is come, yet light is not

Yet light but lesser dark. Something vague on the horizon

Upheaves the severest corners

Of sleep, but leaves us as of then not sensitive to the explosive

Draught wakening senses to their duty; drippingly,

A high peace of morning, a piece of the

Peace, of time in fickle frames unmovable. The-

-Radical takes a walk.

It is how he does his time on this visionary Earth,

Or call it prison, fabrication---it is this fabricated

Intensity of devotion that makes him

Properly diurnal.

In his quakes of pattern,

The radical configures

An equivalent paean for the sun and

Moon. I memorialize the minutes of his life by linking these.

All of him is all of me accumulated, but in frames of death, not

Life, though the radical takes some action to deny his lack of self,

Once fetched together by the sun and once all the frames are single-file

As like the resuscitated breather’s breath, the radical

Enacts his betrayal of me and himself, he takes his walk back

To the moon’s fugitive remaining parts,

Essentially backing the wrong horse, his reasoning a roast

Of change of day, a circular riposte

Unto that offense of passing time, that is, a passing into

The light of day, as if his own reality were more at stake

In a fluxive World. This choice resulted quickly in diffusion, him

With the rest of night among the weltering calm

Palinode, and pallet, of dawn colors---this

To catch the memory of being, as if he was at all

Before I made him wander, by being in the night,

He is from bones to flesh to a frame among frames

Of passing time, a circular riposte

Unto some offense, when to be the footman both

Of a sun and

Moon, independent of the meld of both

Into some other---since in being,

One cannot be, without an Other---

Robs time from the already-flimsy being

Of the radical, makes his realness flee

Into something metaphorical already, even before I write it so:

He has been there before, in the metaphor. He says

This in the garden, and suddenly finds no

More to be found there but tombs, tombs

Garbed in glitz and beads for epitaph of words

Soaking in the petty stylings of truth’s obligatory

Temporalities, and those truths especially of life,

In bleak essay for our dank attachments

Daily to be rid, for sake of his

And any life of radical,

And he lamed by these withered words about it.

Yet they are not idiom

To be put together, the way one as him, but not him,

The way I put together the blueness of the atmosphere

And light through the big tree: with my massive-

-Painter’s hands, I cluck him out his hoot, contrary hoot,

And find I holler answer in

My own mind: he sees himself---in my gusty,

Gutsy absurdness; yet unsated, continues licking at these

Chromatic choirs of light through lewd yew trees.

It was his sun heaved upwards to the other side

Of the planet, for he was there where I cannot be,

The same as maker cannot be the made. He eyed

The sun: it was the same answer---to night’s different gilding,

Artifice both, for both come from my hands; what drapes

The dark of damfool night in a slightest glow of visibility

Rides on the backs of particles of light later, depending on

That ignorant steed, to paint the morning reality instead.

The radical unsheathed by

Dawn, realizes nothing of this wilderness of symbols, but

Sees clouds where they should be, and as is normal, he

Battles certain pained thoughts that, weakened by

Sleep, had almost made a night of his day, this day.

A weal reddens at the rejection

Of moon in its final places, somewhere

In the moon, as it turns inward, a touchy thing:

Its ardor to oppress

The dawn is like a perspective once asleep, then made alive to

Meet the challenge of the old inevitability that will compromise it,

Settling the pitch of night’s end finally upon the cities’

Grace as much upon the valley, and all of this, a slow contumely

Unto that moon, a passive, suffocating greyness to its

Light, leaking away into usurping horizon: the radical

Takes a walk: I am filled with a madness to confess

What he might have gotten away with never affirming,

If he just only lived the lie, that he was born, not made. The

Sketchy, yellow light to heat the frost on grass

To runoff watering lower berths, lower hills. Tell me his

Reality, o nature, or my nature.

A whisper of wind got blown like a charge. Some

Cold glaucoma at first was deadly lush in my wandering radical

Who saw this night in him the horse to back.

As opposed to that

Which took its place, and does, whether I create

Or not; having no alternative.

The sun broke out across the nothing new like an

Omen by the reins. In blowing hymns of rays---

There were pink yellows, majesties of common, virilest

Red into vermilion---the caroled heralding of the sun

Got at him, cornered all the frames

Of him, being so enhanced at soul

By the drooping weight of bell-flowers

Among other garden vesture finally

Mid garofani and rosa venturing

Curled thorns up to meet the oxidation of self’s throne,

He sitting like the sun at the tips of his head, fighting to

Be as massive as the sun, thinking in steps, inconclusive

Frames that want the very flat face of meridian their

Home.---Disinterested, apart, I the sterilest painter

Could only hope his interest tell the story enough,

As if, being a mirror in dark, all that is here is what

Is here. If the sky were conscious of reactions to itself,

But not the source of that, the origin of its own self-

-Most metaphysical; and wearying of no obligated

Approbation/dismay towards a lot of unfelt reality

As tunes this poem here,---then, my

Light might could speak in a spark

Or charge through the yew trees, back

At him, and make him live, more than

One thousand Frankensteins, for the big,

Blue bushes---or what light through staid

Clouds: by the time of this frame the day was obviously day, and

Yet the radical sought some communicant or symbol for this,

Searching for certainty about all the selfhood, anything

As might state its line of reasoning to him,

As if I owed him my logic! I told him life

Only existed so he might put himself at stake,

Risk to regard the brittle branches of the little

Trees as a heft equivalent to the heft of his

Reality, which I painted from scratch; one tree, one instance

Of a tree in the particular, all that was needed.

So it seemed, I was the sun, or wasn’t,

Or was the wisdom of the sun.

I saw time’s rambles. I took a walk this time.

I switched him out; I switched

This mind of mine to strange frames

Of the radical’s within, and moved

That microcosm to another crown,

Throne, another chord for him to

Feel real in hearing: for the royal

Equipage to harp out and just for

Time, for time's dreadfulness in being, bearing out-

-Portals into fiction I spot there in the air I desperately breathe.

This was harder than one could

Think to do. That is, to grab this thing I made

As if I could also be it, know the battle of the sun

And moon my own, yet something different

From that too. To grab-

-All of time’s incessant religion, always multiplying

Into further depths, barely there. You’d have to do it,

Grab it differently, grab different: yes: each and

Every second, make and be a different body for

The frame. You'd have to dismiss the servile

Shadow of fawning publicans that follow you around,

Saying about how you are so great, bickering about when

Which second out of all the seconds should grab you,

That is, me, on my infinite coattails, and kill me off, while moves

All long time along, isolating being from the sun, the moon from

Being; nay any heralding of light’s

Meridian pathway across land and sea,

A suggestive throne but not for any sycophant. There is

A need of mine, that is, to separate the hope to go on,

Debased by now, from the rule of the frames

Over this sucking choir.

A comfort: confusion and pure spectacle proceed with

Chromatism, charisma---the pure hoot, pure hail of the

Commodious reaching of time, and light, and light unfolding;

Telling, heralding itself as pleasance, eden of edens. But

The radical is never there. Nor am I, however the balance

Might go. All that could survive once the both of us fossilize into

The symbols, forms, ratiocinations, metaphors that built us, he

And I, we realize, become with the gradualness of nightfall

A brute spectacle of all these different frames,

And I the painter, I am one who moved my heart of the sun

From its nestled tomb in some headachey beyond beyond

The trees squared in the hills. The hills like lonely

Wizards’ hats that loom, and not one bright finality

. . . . . . .

in the bunch of 'em. This bunch of cosmic minutes out

of time and made of a time that differs from these my,

your dripping frames. In FRANCE, the existentialists,

absurdists and surrealists would think of what I’ve

made so far as so much beauty, malformed by a-

-damned spectacle: of technicolor light: yes: through

famished trees. And yet, how may I take one frame,

and call that my religion: is such a thing not the

same if chosen from any frames’ minutes, droll and

fabulous microcosms shooting like full rays of sun, and

the sun, the ultimate, the viol, singing sadness

out of tune, to show absurd beauty in a sleep? I-

-took a walk. It is impossible to escape the sad

strains of this gay blowing, an impossible poise, a-

-hymn, a waltz of chromatic diligence regarding this

the span, the catalogue of minutes’ colored light in

a day as wide as wanderers in spaces. Cursed,

this demeanor of the sun goes off into cacophony.

In the sewn sky. Bowels, led from an open maw

of time, down. The radical shakes his locks at this nice, religious

consistency of frames. Again, are not the followers of time, like

is the radical, not more than time’s followed rules incarnate?

One can’t, or won’t, babble out a frame of multiples, and call it

questing for the walk he took that morning I had made him to take.

But did I keep my reverie intact: is it

spastic as surreal rays through this moment of a-

-tree, or many trees, this dallied instance: what choral agony is

there to follow, after followers and radicals give up with rhetoric:

questions are not questions; no more were drips of

time the frames of time. No more were suns the last

of a truth; a kindness. There’s millions of suns left.

There's millions of ways the way I walk will leave

the blowing sun the blowing wind---or tiding---of

immaculate change. I took a walk because I was

the radical, the radical was I, a changeling, feeling

out for the code for a being in the sun and in the

moon. For all these sad strains

of waltz broke through religion, time’s religion,

which, after all, is the only religion. To what else

are we forced to adhere, day in, day out: and-

-how is it there’s no God for this hymn of the

beholder: is he beholding gold sides, green sides,

pink yellows? Absurdity is deep

running. It is my rebellion; the rebellion of a-

-wanderer wandering, having no alternative.

To sum up, to instate, clip the infinite to ends,

that is my mission. It is to round out the brittle,

brittle branches of the tree---make the tree

a part of the sun, and walk, with rays blowing in

my face. Dis-organize the senses; break the new

wood. For something in the heart of time's-

-quite idiomatic, allusive, seeming done before,

and yet no further notion of the hymn is taken,

elaborated out of dull surprise. Out of dreamt,

dreamy frames of blithe light in a quiet fury. In

a ghost, a moving ghost of meaning. God’s ticking

clock. So what is it I'm always speaking of: I do

not know, and it makes me anxious to move on

from whatever it was that rose, having no

alternative.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

belit sağ: Excessive Ideas

by Chi-hui Yang

In belit sağ’s video practice, the photographic image is an excessive object—an object whose meaning is shaped by forces beyond its frame, wields and condenses social power, and controls bodies and behaviors. The image is also one which demands. It structures seeing as a political act and insists on response, analysis, and accountability. It is capable of violence, of telling truth, half-truth and falsity, and of reproducing itself. It possesses radical possibility.

sağ is a collector and deconstructor of images. Central to her practice is an inquiry into how state power and violence flow through the image; how production, circulation and interpretation of photographs and video reveal optical regimes, shaping the visible or invisible, the accountable or forgotten. sağ builds her videos from images which mold and reinforce social behaviors and narratives: newspaper archives, social media, cinema, propaganda tapes, surveillance video, television news. Through gesture, collage, abstraction, and most importantly, text, her works examine how ideology is embedded in representations of reality, and the spells these forces are capable of casting.

sağ is concerned with the nation, race and ideology—social formations which are often called upon to justify violence. An artist from Turkey based in Amsterdam, the subjects of her first-person video essays are the charged dynamics created by the relationship between Turkey’s borders and national identity: Ayhan Çarkın, a paramilitary policeman understood to have killed hundreds of Kurds on behalf of the Turkish state; memories of conflict on the Turkish-Syrian border; and in her most recent work, the murder of Turkish and Kurdish individuals by a German Neo-Nazi group. The titles of her videos reflect that her inquiry is not just about politics, but the complicity of the image within: my camera seems to recognize people (2016), and the image gazes back (2014), overexposed (2017), cut-out (2017), grain (2016). Her videos are staged as encounters with images whose real and symbolic power require interrogation, self-reflexive conversations between her and fragments of video or grainy photos about the creative and political act of filmmaking itself, and the role and precarity of the artist in conducting it.

In Ayhan and Me (2016), sağ examines notions of artistic production, censorship, and control through her relationship as an artist with the images of Ayhan Çarkın. A video about its own making and a critique of social and artistic institutions, it charts the trajectory of the video from being one about Çarkın, to one about the symbol of Çarkın, and its power to censor. In 2015, sağ was asked to create work for an exhibition supported by the Istanbul arts center Akbank Sanat. When the gallery learned that the piece would concern Çarkın, it bowed to political pressure and censored the project. In the fourteen-minute piece, she crumbles, bends, over exposes and obscures a photograph of Çarkın, exercising her own power over it even while the photograph determines the parameters of her video. She muses “questioning who manipulates who, is a part of [her] practice, even perhaps has become its backbone in this climate of war.”

In an earlier work, and the image gazes back (2014) she examines the relationship between the political act and mass-circulating media images, real and fictive, by asking what informs and distinguishes one’s actions from the representations of them. Weaving together references to ISIS, Twitter, Dog Day Afternoon, photographs from the occupation of television stations during the Romanian Revolution, and the television broadcast of the 1982 Spanish Parliament Coup, she asks whether there is a distinction between images capturing us and us being captured by images, pointing to “images that reimagine the real and on the other hand, realities that look like they are faking fiction.”

In her most recent videos, (Against) Randomness, overexposed and cut-out (all 2017), sağ examines the National Socialist Underground (NSU) murders, where between the years 2000-2007, Turks and Kurds were targeted and killed in Germany by this Neo-Nazi group. The three together form an inquiry into the construction of history, memory, and the optics of justice. (Against) Randomness calls for the necessity of narrativization—the linking of related histories together to reveal patterns of violence and abuse of power. In this text-driven video, amidst fragmented images of everyday life, she muses on remembrance, forgetfulness, and what allows traces of lives made invisible to be seen. In the video she writes, “storytelling is resistance against the perception that life is a series of random events.”

This idea of forging connective tissue as resistance animates cut-out, an examination of the media photos of individuals murdered by the NSU. Moving through each individual’s newspaper image, she asks what they tell us—what the lighting, background, quality and cropping reveal about the individuals. Intimate portraits of the victims’ lives are offered through holiday photos, studio portraits, and passport images. What do the excesses of these images say? What isn’t included in the images that we can draw out, what does a background color or a gesture reveal, and how are these separate lives linked? While sağ intentionally omits images of violence, its spectre is conjured in the mind of the viewer, through the act of sewing together the connections between the disparate yet intimate lives on display. What cannot be seen but only imagined often exceeds reality and can operate as a powerful political tool and creative device.

The architectural and cultural biases built into the criminal trials of the NSU murders are explored in overexposed. sağ uses a schematic of the Munich courtroom where the trials were held, choosing to dissect the tightly controlled lines of sight between those occupying the room. The denied visual connections between victims, their families, witnesses, lawyers, and public are accounted for while transcripts reveal embedded biases favoring the accused. The relationship between optics and justice is suggested: to deny the emotional and political insights that come from access to facial expression and eye contact is to deny solidarity, accountability and legibility.

Sağ’s videos are incantations orchestrated to demystify the photographic machinery of ideology, to not only hold power accountable, but to counter it with critical deconstruction. They ask how images accumulate meaning and influence, what imprint they have on us and how this mark can shape actions and intentions both present and future. Confrontations both urgent and necessary, her essayistic encounters press for greater truths in a moment when the image’s hold on veracity has been obscured.■

Chi-hui Yang is a curator based in New York. He is currently Program Officer for Ford Foundation’s JustFilms initiative, a global effort that supports non-fiction filmmakers and organizations whose work addresses the most urgent social issues of our time. As a curator, he has presented programs such as: MoMA’s Documentary Fortnight, “Lines and Nodes: Media, Infrastructure, and Aesthetics” (2014, Anthology Film Archives) and “The Age of Migration” (2008, Flaherty Film Seminar). From 2000-2010 he was director of the San Francisco International Asian American Film Festival. Yang is also an instructor at Brooklyn’s UnionDocs and has served as an adjunct professor at the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism and Hunter College. He earned a master’s degree in film studies from San Francisco State University and a bachelor’s degree in political science from Stanford University.

This essay was written for the exhibition belit sağ: Let Me Remember at Squeaky Wheel Film & Media Art Center. On view January 19–April 14, 2018, Tuesday–Saturday, 12–5pm. The gallery is free and open to the public.

Still: belit sağ. kesik (cut-out), 2017/2018, Netherlands/Turkey. HD video with sound, 3min40sec. Courtesy the artist.

0 notes