#because I enjoy certain kinds of meat but I don’t support factory farms and animal cruelty

Text

I’m vegetarian for ethical reasons but food I get for free at work doesn’t count

#my rationale is if I don’t pay for it and I eat food that’s going to be thrown out at the end of the day anyway then#im not supporting the meat industry#because I enjoy certain kinds of meat but I don’t support factory farms and animal cruelty

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Earlier this week marked 19 years of vegetarianism for me. The last meal in which I intentionally ate meat was at a small Mexican restaurant in Peoria, Illinois in 2002. I was with my friends Dustin and Vanessa. We had driven from Tulsa, Oklahoma (our hometown) to Milwaukee to see a bunch of hard air and screams bands play at “level plane fest”. Level Plane Records was perhaps my favorite record label at the time, and most of our favorite bands of the moment were playing so we hit the road. It was a very very long drive. I can’t remember if we went non-stop of what. Dustin would remember. Anyway, over the 2-3 years leading up to that point There we’re more and more vegans in my life and my understanding of the relationship between humans and the rest of the world was evolving in a way that saw humans as highly destructive. That hasn’t changed much, but it has evolved further to a more nuanced thinking… I’ll write about that more at some point too.

Anyway, in Milwaukee we hung out with a bunch of these big bearded and tattooed hardcore dudes. A lot of of them were vegan and just absolutely loved food. I saw how being vegan wasn’t a sacrifice for them, but actually an Avenue to appreciate food more. They celebrated their food so much and seemed to enjoy it more because it wasn’t harming other animals. I should say that I 100% think of humans as animals all the time, and this way of thinking is part of why I wanted to stop eating meat. Yes there are differences between us and other animals, and one of the main differences is our relationship to food and technology. We have reached a point in our history, technology, culture, or maybe even evolution, in which we could exist almost entirely without consuming animal products. We have excellent alternatives for just about every use of animal, and I felt like I wanted less of my money going to support the wholesale slaughter of millions of animals, and less of my money supporting the treatment of animals as instruments of capitalism in which their genetics are bred to maximize profits, etc.

I say less of my money because I have never found that going fully vegan is easily sustainable in my life… at least yet. I actually think I could probably be vegan now more easily than ever, especially in New York City, but I’ve developed a balance or level of harm-reduction that I am comfortable with, proud of, and that works for me in many ways. I have never wanted to play “end game” with my reduction of animal harm because I honestly don’t think it’s possible to follow that logic to an end that doesn’t involve suicide. Even vegans know this, but unfortunately some do fall for the trap of all-or-nothing thinking. I think especially when you are young peer pressure, and social and ideological fervor tend to overcome thinking and acting in moderation. It’s really all about finding the level that you are comfortable with, and that sense to you. I think I knew this for years, but sort of subconsciously I felt that my approach was the most sensible for everyone. I didn’t understand pescatarians, flexitarians, freegans, or meatless Mondays. Nowadays I think these are wonderful and amazing.

I also didn’t initially switch to this diet for environmental reasons. It is now well know that factory farming of meat (especially beef) and the various fishing industries have caused and are causing catastrophic environmental and ecological damage, some of which may be impossible to heal. But in 2002 I didn’t know about those factors. All I knew was when I ate fried chicken, I absolutely loved it, but if I saw some veins and tendons near the bones I would start to feel nauseous. I could not get past feeling like a cannibal, or that this life was slaughtered without consequence just so I could have a greasy salty meaty meal. I wasn’t the type of person to see a chicken and think is was adorable and want to hug it. I have also been a long time critic of aesthetic value, at least in my head, especially when it is applied to humans, animals, or plants. Just because something is cute doesn’t mean we should put more effort into saving it, or value ugly beings less. This is adjacent to ableist, eugenicist, or racist thinking and I always felt suspicious of it, but only in recent years have I started to become able to verbalize my feelings around that. So yes, my vegetarianism intersects with my aesthetic sensibilities. How could it not?

Since I have been vegetarian more and more research has been published that has made my choice feel more “right” for me - in that the research shows how a vegetarian diet aligns with my view of how humans can better exist as part of the earth. It has also gained a lot of popularity which is wonderful in many ways. Meeting other vegans and vegetarians is more common and less novel now. I won’t get into all the ridiculous comments and questions I’ve heard over the years, often times meant to be insulting or somehow make fun of my diet choice. Those comments happen with much less frequency now, if at all, which feels like evidence of a major cultural shift. I do eat dairy and eggs, technically making me an ovo-lacto-vegetarian. I love ice cream and cheese and eggs dearly and eat them often. I make an effort to buy eggs from free-roaming pasture raised eggs as much as I am able. I buy and drink mostly soymilk. If I buy dairy I try to buy “organic”, but honestly I am more lenient with dairy. A lot of cheese is made with animal rennet, which is an enzyme from the stomach of certain animals. If a vegetarian dairy cheese (one made with rennet from microbial enzymes) is available I will usually get that instead, but not always. I sometimes eat things made with gelatin, which is a byproduct of meat production and is essentially a kind of meat product itself. I sometimes eat Thai curry or Korean kimchi, or Japanese sauces or soups that I know probably have fish or shrimp sauce in them. For the most part I try not to. Those exceptions drive a lot of people crazy, especially meat eaters it seems. They seem to think that I have “rules” and that if I break those rules somehow it disqualifies, discredits, or undermines my vegetarianism. For me is more of a big-picture reduction. If over the course of a few months I feel like I’ve made too many exceptions to my boundaries, then I’ll tighten up a bit. Over the course of 19 years this has helped me to reduce my environmental impact and harm to non-human animal life by a massive amount.

I’ve been considering starting to eat some fish or maybe certain other animal products next year after the 20-year mark. I’d like to explore sustainable fish or meat and see what health impacts it has if I eat it maybe 2 or 3 times a month. The easy b12 and omega3 source is the main thing I’d like to figure out. Plus it’s easier to find and afford sustainable fish and meat now. I just don’t know how I’ll feel about eating other animals so directly and intentionally. That might keep me vegetarian for many years to come. That, and impossible burgers. Yum.

0 notes

Text

Assignment 9 Final Draft: In Depth Analysis of Food Inc. and Symphony of Soil

The long-form documentary can be used to effectively tell stories that have been historically left untold. Symphony of Soil is an interactive documentary which relies largely on interviews from scholars in the field of geology and environmental studies. Food inc., on the other hand, is more of a reflexive documentary, which demands viewers to think about and criticize the current system. Both films strengthen the narrative that the current way in which most of the food–especially in this country–is farmed is unsustainable, unhealthy, and frankly, unsettling.

I thoroughly enjoyed both of these films as someone who has grown up having a close relationship with food. I was raised in a Jewish family, where part of the culture is thinking about our next meal, sometimes even while we are eating one. We were all big meat eaters until 2016, when my dad had to have an aortic bypass surgery at the age of 49. He would have been one in a long line of Cohen men who had experienced a heart attack before the age of 50, but his fitbit alerted him that his heart was skipping out of beat. He went to his doctor, who told him if he hadn’t checked in, he would have had a heart attack within the year. He had a buildup of plaque in his arteries, which were close to preventing blood flow. This is all a lot of information, but it changed us as a family, and definitely my personal eating habits. He stopped eating meat completely, and began pursuing a plant based diet to prepare and eventually heal from his surgery. It was around this time that I watched the documentary What the Health, which highlighted how certain food and medical industries are corrupt and not prioritizing the health of the American people. That documentary was so powerful, I also stopped eating meat altogether and paid attention to who was selling me my food, and who was telling me it was “good for me.” This is when I felt the power of the long-form documentary.

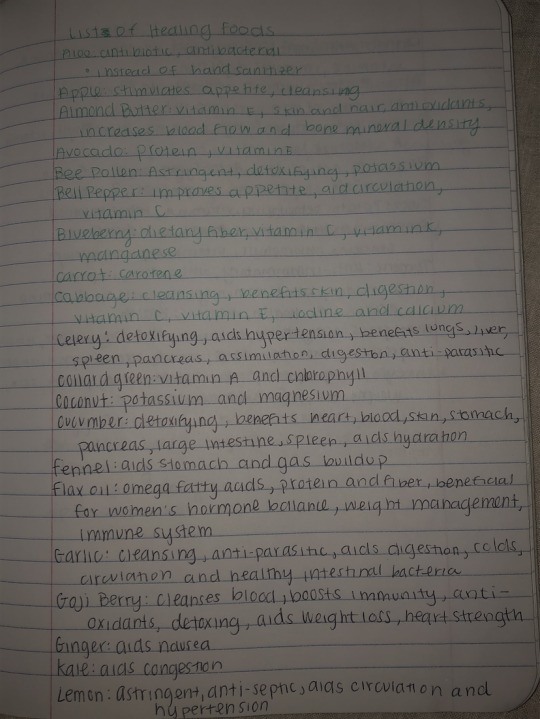

Personal Photo of healthy foods from 2016 with Healing properties.

Documentation of The Dance Between Soil, Food and Humans

The first film, Symphony of Soil captured many images and videos of different types of soil. It also portrayed the connection that humans have made with nature through visuals of the doctors and scientists in the film digging into soil and holding it in the palms of their hands. In reality, soil supports all life and holds us. The main idea with these visuals is that soil is concrete, so concrete, in fact, that we can hold it in the palms of our hands. This is an important factor, as many environmental issues are not taken seriously since they are somewhat less concrete and able to be seen, like climate change.

Every time a new expert talked about a new type of soil, the camera panned over different natural places, including but not limited to, Norway, Hawaii, India, California and New York. Paired with these landscapes were musical tracks that aimed to match the culture of the given setting. The film aimed to educate about soil as the foundation of human life, and this was achieved with visuals of man walking within nature beside scenes of animals walking within nature. These types of scenes helped curate the story of how nature is all connected–the ocean, the soil, animals, and organisms.

As the film progressed, it transformed into a story of how soil has been ruined by us, even though we think it exists for us. The viewer was told that older soil can support any kind of plant life, because it is very nutrient rich. However, agriculture requires constant tilling of the soil, which means it is reborn often. This is a result of the Green Revolution, which really wasn’t green at all; we began using chemicals on farms to increase output. We have increased the runoff of dangerous chemicals into waterways and onto other farms with unintended consequences of eventual decreased output. This lower output comes as a result of degraded soil by these chemicals. Organic farming, which is really just traditional farming, is the response to undo the green revolution and its effects on the soil. The film also suggests other solutions such as composting. But any solution serves as a means to the end of improving the quality of the soil. By the end of the film, the viewer is asked to change the way we think about soil: not as dirt, but rather as a material of life.

The other documentary, Food Inc., featured many different kinds of clips outlining the relationship between people and food. These clips included those of different kinds of factories, farms, restaurants and grocery stores, which helped explain how much of the industrial food industry uses greenwashing, with images of systems that no longer exist. Moreover, the footage has a revealing nature to it, and is organized in such a way which tells a story that most people are not aware of. This lends itself to the nature of the film, which asks consumers to be more aware of how our purchases affect the food and farming industry.

Food Inc. focuses on the fact that the way we eat has changed drastically in the last 50 years. Most of the food available to us is owned by a small group of national corporations. As the narrator tells us this, a scene of business men walking up to a factory in a field is played. Food Inc.’s purpose is to show the viewer how we have been distanced from our food, what we don’t know about it, and what we can do to make a difference. We are told over and over again in this film how big business has cut costs to produce the food put on our plates. Interviews are conducted with farmers stuck under the stronghold of these companies, with organic farmers, food experts and ethical corporations.

The narrative is split into nine digestible sections: fast food to all food, a cornucopia of choices, unintended consequences, the dollar menu, in the grass, hidden costs, from seed to supermarket, the veil, and shocks to the system. In the first section, the ethics of industrial farming are first called into question with information about the conditions of the animals and the workers. In this section, there were also captions of the fact that two of these companies (Tyson and Perdue) declined to be interviewed for the film. In the second section, the topic of corn was rampant, as it is in our food, though we are convinced otherwise through the illusion of diverse ingredients on our food labels. In the third section, e-coli was highlighted as a result of corn feed in animals, and if animals get e-coli, so do the crops which are fertilized by their wastes. Though the simple solution of using grass feed for 5 days would reduce e-coli in animals by 80%, the corporations prefer to invest in technological innovation, rather than taking it back to basics. In the fourth section, the unfortunate reality of price came into play with the fact that many people have to balance the cost of buying vegetables with the cost of medication for diseases that occur as a result of eating unhealthy. This idea is always crazy to me; when we talk about the fact that the people living in one of the most agricultural states in the country (California) can’t afford vegetables it sounds like a developing country, not one of the most developed ones. In the fifth section, more ethical issues were discussed, this time dipping into government subsidies working against the environment and supporting unsafe practices. In the sixth section, business was blamed for pollution, but also portrayed as a possible part of the solution. In the seventh section, Monsanto was featured as a company who has found legal ways to own certain crops, which endangers the livelihood of farmers. They also declined to be interviewed for the film. In the eighth section, the corruption of the American government by the aforementioned large corporations was revealed. In the final section, consumers were empowered to vote with our dollar when possible by purchasing organic products.

Reviews

Reviews of the Symphony of Soil included one by the Bard Center for Environmental Policy, which claimed that the film “put faith in her viewers’ intelligence by allowing science to play a central role in her film, avoiding the tendency of many environmental films to build their argument by demonizing the ‘other side’” (Macgregor 2013). Another review by Variety described it as, “a seemingly endless procession of organic farmers from Washington state to Wales to India wander their flourishing fields, displaying the fruits of the ‘dance with nature’ that is organic agriculture. With minor variations, all make the same strong case for a simple solution to soil exhausted by plowing, chemical fertilizers and pesticides: Give back to the soil what was taken from it and it will endlessly replenish itself” (Scheib 2013). I would agree with this review that the film was a bit repetitive, but definitely got the point across. The documentary aims to educate about what can be done for soil, and what soil does for us. There is no direct call-to-action, per say, but it is clear cannot ride the current path, as it will lead to an “imminent agricultural Armageddon, with its attendant barren soil, polluted waters and birth defects” (Scheib 2013). I wasn’t completely captured by the film, but I know the issues presented are important and the information seemed accurate based on the presentation of the facts by educated professionals.

Of Food Inc., one reviewer at the New York times said it was, “an informative, often infuriating activist documentary about the big business of feeding or, more to the political point, force-feeding, Americans all the junk that multinational corporate money can buy. You’ll shudder, shake and just possibly lose your genetically modified lunch” (Dargis 2009). However, the same reviewer also claimed it was “also over before the issues have really been thrashed through. And while I appreciate the impulse behind the final checklist that tells what viewers can do for themselves and the world (er, eat organic), given everything we’ve just seen, it also registers as far too depressingly little” (Dargis 2009). In another review by the Washington Post, a reviewer states, “Those expecting an unfair broadside against the food industry will be pleasantly surprised by “Food, Inc.” Instead of scoring cheap points by disgusting viewers with the messy inside workings of a slaughterhouse, director Robert Kenner sticks to relaying the facts” (Bunch 2009). The same review claimed that though “the documentary sometimes feels a little one-sided, lack of participation by companies such as Monsanto Co. and Tyson Foods Inc. ensured such a result” (Bunch 2009). I think both of these reviews are valid, as I felt similarly. I thought the documentary did a good job of bringing attention to the issues at hand in an organized and accessible manner. However, we can always say they could have done more. Personally, I found Food Inc. not only effective, but also entertaining.

Closing Thoughts

In conclusion, both films supported the narrative that the current way in which we are farming is unsustainable, unhealthy, and unsettling. Symphony of Soil used science to bring light to the basics of life and how humans have disrupted them. Food Inc. revealed lesser known facts about the way in which our food has changed in the past 50 years, and what we should do to change that. I preferred Food Inc., as I felt the narrative was easier to connect with and follow. It also had a clear call-to-action approach, which Symphony of Soil lacked. The problems outlined in Food Inc. feel more relevant than those in Symphony of Soil, and I think that is increasingly important in mobilizing public opinion and activism.

Word Count: ~1800 Words

Question: How can film/documentary be more widely accessible forms of knowledge?

Works Cited

Bunch, Sonny. 2009. “MOVIE REVIEW: 'Food, Inc.'” Accessed March 29, 2020.

https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2009/jun/19/movie-review-food-inc/

Dargis, Manohla. 2009. “Meet Your New Farmer: Hungry Corporate Giant.” Accessed March 29, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/12/movies/12food.html

Garcia, Debora K.[กรมพัฒนาที่ดิน แชนแนล LDD Channel]. (2018, November 23). Symphony of Soil [Video file]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tDZVKMe2FTg

Kenner R. (Producer & Director). (2009). Food Inc. [Film]. Magnolia Pictures.

Macgregor, Marnie. 2013. “Film Review: Symphony of the Soil.” Accessed March 29, 2020. https://www.bard.edu/cep/blog/?p=4155

Scheib, Ronnie. 2013. “Film Review: ‘Symphony of the Soil.’” Accessed March 29, 2020. https://variety.com/2013/film/reviews/film-review-symphony-of-the-soil-1200725684/

0 notes

Link

American Grassfed Certification Now Assures the Highest Quality for Beef & Dairy Products Dr. Mercola By Dr. Mercola You’re probably aware that the food industry has the power to influence your eating habits through the use of advertising and lobbying for industry-friendly regulations. But did you know the U.S. government actually funds some of these activities through the collection and distribution of taxes on certain foods? And that by doing so, the government is actively supporting agricultural systems that are adverse to public and environmental health, and discouraging the adoption of healthier and more ecologically sound farming systems? The beef industry in particular appears to be rife with corruption aimed at protecting big factory-style business rather than the up-and-coming grass-fed industry. As explained in Washington Monthly:1 “Imagine if the federal government mandated that a portion of all federal gas taxes go directly to the oil industry’s trade association, the American Petroleum Institute [API]. Imagine further that API used this public money to finance ad campaigns encouraging people to drive more and turn up their thermostats, all while lobbying to discredit oil industry critics … That’s a deal not even Exxon could pull off, yet the nation’s largest meat-packers now enjoy something quite like it [W]hen you buy a Big Mac or a T-bone, a portion of the cost is a tax on beef, the proceeds from which the government hands over to a private trade group called the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association [NCBA]. The NCBA in turn uses this public money to buy ads encouraging you to eat more beef, while also lobbying to derail animal rights and other agricultural reform activists, defeat meat labeling requirements, and defend the ongoing consolidation of the industry.” Federal Tax Helps Beef Industry Promote Beef In a nutshell, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) beef checkoff program2 is a mandatory program that requires cattle producers to pay a $1 fee per head of cattle sold. It’s basically a federal tax on cattle, but the money doesn’t go to the government but to state beef councils, the national Cattlemen’s Beef Board (CBB), and the NCBA. All of these organizations are clearly biased toward the concentrated animal feeding operation (CAFO) model. The money is collected by state beef councils, which keep half and send the other half of the funds to the national CBB, headquartered in Colorado, which is in charge of the national beef promotion campaign. Nationwide, the beef checkoff fees add up to about $80 million annually. As the primary contractor for the checkoff program, the NCBA receives a majority of the checkoff proceeds, which is used for research and promotion of beef. But while the beef checkoff program began with the best of intentions, aiming to help struggling ranchers by pooling their money to pay for the promotion of beef, discontent over how the money is being used has grown over the years. CheckOff Program No Longer Benefits Small Ranchers — It Harms Them Many cattle ranchers feel they are being forced to pay for activities that go against their environmental or ethical views on animal welfare and environmental stewardship, for example. Moreover, while being a federal tax, the government has virtually no oversight over how this checkoff money is used. As reported by Harvest Public Media:3 “Checkoff officials say … every dollar collected by the checkoff delivers $11.20 in return. Among its successes is a series of iconic commercials called ‘Beef, it’s what’s for dinner.’ But there is a lot more to the beef checkoff than meets the eye. That $1 assessment, critics … say, flows with limited oversight to state and national interests. Sellers must pay even if they don’t believe they have any say over who gets the money, or why. And they must pay even if they believe the fund advances the interests of multi-millionaire ranchers against their own … As many as a fourth of the nation’s 730,000 ranchers … have complained for years that the checkoff has become a billion-dollar bonanza for big ranchers, industry executives and giant beef packers. Federal statistics show larger more efficient cattle operations are forcing out smaller ranchers and feedlots.” One case in point: When a trade complaint was filed against Mexico in 2014, NCBA opposed anti-trust enforcement against the three multinational corporations that control more than 80 percent of the beef packing industry. The NCBA also supports the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which allows for low-cost beef imports, thereby undercutting American ranchers.4 What’s Good for Large Meatpackers Often Hurts Small Ranchers Also, since the $1 per head fee is mandated by federal law, checkoff funds are not allowed to be used for lobbying or political contributions. However, critics have argued that both state beef councils and the national beef board have strong ties to beef industry lobbying groups — some of them even share office space.5 At the national level, a majority of the checkoff money gets funneled into the NCBA, which has a strong political voice in the Washington D.C., where it has spent millions in campaign contributions and lobbying efforts. According to Harvest Public Media:6 “In the 2014 mid-term elections alone, the NCBA gave nearly $800,000 to mainly Republican political candidates … That amounts to more than 98 percent of total checkoff revenue and 82 percent of NCBA’s total budget, according to a recent lawsuit filed by small producers … That same lawsuit claims that the NCBA controls half the seats on the beef checkoff’s contracting committee. ‘I think it is a broken system,’ said Wil Bledsoe, president of the Colorado Independent CattleGrowers Association … ‘I don't want them using my money to fight my livelihood like they have been,’ he said. ‘What's good for packers isn't usually good for the little guy, and vice versa. So how can they claim to represent both?’ … And government monitors overseeing the program are aware of the problems, said one former U.S. Department of Agriculture official. ‘The administration is well aware that the NCBA has misappropriated producer money and the NCBA has helped defeat policy reforms that would have helped small producers,’ said Dudley Butler, who resigned as a top USDA official in 2012. Butler, a lawyer, says the checkoff is nothing more than an ‘illegal cattle tax.’” The Livestock Marketing Association has been calling for the USDA to hold a referendum on the possible termination of the beef checkoff, and more than 146,000 cattle ranchers have signed the petition.7 In 2011, the national checkoff program for pork was terminated by a nationwide referendum, but the USDA declined doing the same for beef, saying it would not consider a referendum on the beef checkoff anytime soon.8 Still to this day the fight to terminate the program continues. Beef Council Accountant Investigated for Embezzlement Misuse of checkoff funds is not the only problem ranchers are railing against. Federal authorities are now investigating embezzlement charges against Melissa Morton, a former Oklahoma Beef Council accounting and compliance manager.9 According to the council’s own internal investigation, Morton (who was promptly fired), stole $2.6 million in beef check-off funds between 2009 and 2016. As reported by the Cornucopia Institute: 10“In 2014, according to the council’s latest federal tax records, the group took in $3.6 million in revenue. That same year the compliance manager allegedly embezzled $316,231, nearly 9 percent of the state beef council’s annual revenue.” In 2016, Morton allegedly forged 131 checks totaling nearly $557,790. According to Mike Callicrate, a cattleman and founding member of the Organization for Competitive Markets, news of the embezzlement added to “the suspicion that … our dollars are not being utilized in a way that actually benefits the cowboy that’s paying the beef check-off.” Embezzlement aside, critics have also pointed out the exorbitant salaries collected by NCBA management — salaries paid for by checkoff dollars collected from ranchers. In a 2015 article, California cattleman Lee Pitts wrote:11 “…the last info I was privy to about the salary of NCBA's CEO, Forrest Roberts, was from his 2013 federal tax forms when he was paid $428,319. That's extravagant enough but according to a Cattleman's Beef Board big wig who called me, Mr. Roberts is now allegedly making $550,000 per year! … I wouldn't have a problem if Mr. Roberts was being paid with NCBA dues money, that's their money and let them spend it how they want. But according to my source, 72 percent of Robert's salary is paid by the beef check-off because that's how much time the NCBA says he spends on check-off matters. 72 percent! The NCBA sure couldn't pay that kind of a salary if they had to live off dues, now could they? … According to one source, there are at least 10 people working for the check-off who are making more than $290,000 per year! NCBA paid out $13 million in yearly salaries and 82 percent of NCBA's budget comes from your check-off dollars.” Checkoff Funds Used to Promote International Beef Last year, the Ranchers-Cattlemen Action Legal Fund, United Stockgrowers of America (R-CALF USA) filed a lawsuit against the USDA, claiming the beef checkoff tax is “being unconstitutionally used to promote international beef, to the detriment of U.S. beef products and producers.”12 According to R-CALF USA CEO Bill Bullard: "The Checkoff's implied message that all beef is equal, regardless of where the cattle are born or how they are raised, harms U.S. farmers and ranchers and deceives U.S. citizens. Despite what we know to be clear evidence about the high quality of beef raised by independent U.S. cattlemen, we are being taxed to promote a message that beef raised without the strict standards used by our members is the same as all other beef, a message we do not support and do not agree with." R-CALF USA’s co-counsel J. Dudley Butler of the Butler Farm & Ranch Law Group PLLC, added: "This is not only a battle to protect constitutional rights but a battle to ensure that our food supply is not corralled and constrained by multi-national corporations leaving independent farmers and ranchers as mere serfs on their own land." The lawsuit was filed in response to Montana Beef Council’s ad campaign for Wendy’s — a fast food chain whose hamburgers can contain meat originating in 41 different countries. The NCBA also has a history of promoting beef, regardless of origin, which is a significant detriment to the ranchers paying the checkoff fees that pay for all this advertising and marketing. The NBCA promotes the idea that "beef is beef, whether the cattle were born in Montana, Manitoba, or Mazatlán” and, joining forces with trade groups representing both national and international meat-packers, the NCBA also fought against the USDA’s implementation of country-of-origin labeling (COOL), and has been tireless in its opposition against demand for higher standards in the treatment of animals. Pitts’ article also points out that NCBA’s CEO has clear conflicts of interest that color the organization’s stance on things like the use of veterinary drugs. Prior to becoming the CEO of NCBA, Roberts held marketing and sales positions with Upjohn Animal Health (which merged with Pharmacia Animal Health and later Pfizer Animal Health) and Elanco Animal Health’s beef business unit. “Gee, do you think he might be a bit prejudiced when it comes to antibiotics, hormones, and natural versus chemically produced beef?” Pitts writes.13 Great News: New Grassfed Dairy Standard Introduced! Fortunately, you need not worry as there is a new emerging alternative certification that will bypass most of this nonsense. The American Grassfed Association (AGA) recently introduced much-needed grassfed standards and certification for American-grown grassfed dairy,14 which will allow for greater transparency and conformity. Prior to this certification, dairy could be sold as “grassfed” whether the cows ate solely grass, or received silage, hay or even grains during certain times. As reported by Organic Authority:15 “The new regulations are the product of a year’s worth of collaboration amongst dairy producers like Organic Valley as well as certifiers like Pennsylvania Certified Organic and a team of scientists. ‘We came up with a standard that’s good for the animals, that satisfies what consumers want and expect when they see grass-fed on the label, and that is economically feasible for farmers,’ says AGA’s communications director Marilyn Noble of the new regulations. The standard will be launched officially in February at the American Grassfed Association’s annual producer conference at the Stone Barns Center for Food and Agriculture in New York State, though the exact start date for certification remains to be determined.” Considering how important a cow’s diet is when it comes to the quality of its milk, especially when we’re talking about RAW milk, I would strongly advise you to ensure your raw dairy is AGA certified as grassfed (once the certification becomes officially available). USDA Grassfed Beef Label Rescinded Also be sure to look for the AGA’s grassfed label when buying grassfed meats, as in January, 2016, the USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) rescinded its official standards for the grassfed beef claim.16 According to the AMS, a review of its authority found the agency does not have the authority to develop and maintain marketing standards, hence it had to eliminate its definition of “grassfed.” The USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS), which approves meat labels in general, still approves grassfed label claims. However, producers of grassfed meats are free to define their own standards. According to the AGA, “FSIS is only considering the feeding protocol in their label approvals — other issues such as confinement; use of antibiotics and hormones; and the source of the animals, meat, and dairy products will be left up to the producer.” In other words, a producer of “grassfed beef” could theoretically confine the animals and feed them antibiotics and hormones and still put a grassfed label on the meat as long as the animals were also fed grass. As noted by the AGA at the time:17 “The unfortunate thing for producers who have worked hard to build quality grassfed programs is that, with no common standards in place, they will be competing in the marketplace with the industrial meatpackers who can co-opt the grassfed label. Once again, consumers lose out on transparency and an understanding of what they are buying. Grassfed has always been a source of some confusion, but not, with no common standards underpinning it, consumers will find it increasingly difficult to trust the grassfed label. Like other mostly meaningless label terms like natural, cage-free and free-range, grassfed will become just another feel-good marketing ploy used by the major meatpackers to dupe consumers into buying mass-produced, grain-fed feedlot meat.” When Buying Grassfed Meat, Look for the AGA Grassfed Label On the upside, the AGA grassfed standards are more comprehensive and more stringent than the AMS standards were. So, to ensure you’re actually getting high-quality grassfed beef, be sure to look for the AGA grassfed label on your beef as well as your dairy. No other grassfed certification offers the same comprehensive assurances as the AGA’s grassfed label, and no other grassfed program ensures compliance using third-party audits. Alternatively, get to know your local farmer and find out first-hand how he raises his cattle. Many are more than happy to give you a tour and explain the details of their operation. Barring such face-to-face communication, the AGA grassfed logo is the only one able to guarantee that the meat comes from animals that: Have been fed a 100 percent forage diet Have never been confined in a feedlot Have never received antibiotics or hormones Were born and raised on American family farms (a vast majority of the grassfed meats sold in grocery stores are imported, and without COOL labeling, there’s no telling where it came from or what standards were followed)

0 notes