#he’s so silly and deranged and burdened by The Horrors

Text

this is yuuta okkotsu to me if you even care (the blood isn’t his. he ate someone.)

#like yes he occasionally has bouts of violent homicidal rage. but he also needs a xanax prescription.#he’s so silly and deranged and burdened by The Horrors#okkotsu yuuta#yuuta okkotsu#yuta okkotsu#okkotsu yuta#jjk#jujutsu kaisen

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

🌙 — ALL ABOARD ! The HMS PROMETHEAN welcomes ( AMBROSE SHAW ) to the expedition in their capacity of ( THE MARKED ). They are ( FORTY YEARS OLD & CISMALE ) and might be painted as ( ZACH MCGOWAN ). When you strike up an acquaintance, address them as ( HE/HIM ). Their deeds on land precede their arrival — people say they are ( COMPELLING, CUNNING, and STEEL-WILLED ) but ( VAINGLORIOUS, RECLUSIVE, DISTRUSTFUL ) when the tide turns. Their purpose aboard the Promethean falls in line with ( ESCAPING THE SINS OF HIS PAST — BY ANY MEANS ).

HISTORY

I. Ambrose and his younger brother are born to a woman who has fallen from grace -- Elizabeth Shaw is by no means remarkable, but she used to be something, and from what Ambrose can remember of her, she always despaired over what she could have been. Her family was quick to turn their gaze when they discover she’s been leading a married man on an affair that has ended in a swelling at her belly and no ring on her finger. She’d been no older than eighteen when the cast her out, and just like that, any mention of her was struck from the books. She pleaded with her lover to show the kindness he’d promised with gentle words in her ear, but he was too poor to even entertain the thought of ruining his own bit of kingdom to try and maintain her own. Ambrose is born not long after Elizabeth Shaw has found her place in a brothel in the slums. It is here that he grows up, an ugly and unremarkable child, running secrets back and forth from room to room in exchange for the skill to read and write. His mother does not so much as acknowledge him, or William, for that matter.

II. He doesn’t know who does it, never bothered to ask, but when Elizabeth dies -- he is twelve, then, and William is nine -- someone comes to get her. That someone is a cousin by the name of Cunningham, distant but wealthy, who’d been close to Elizabeth. Older, yes, but close. He’d been searching for her a long time, he explains to her boys, who look so much like their mother it’s almost astonishing. Cunningham takes them both under his wing and sweeps them out of the slums of London without so much as a second thought. Ambrose doesn’t trust him, and the first year is... difficult. They know their letters, but neither of them are educated, and both brothers drag their heels in the dirt trying to hold onto the rowdy beasts that have taken root in their chests. It is not until Ambrose discovers his love of history that he truly settles, and the difference is like day and night. Cunningham plies Ambrose with historical texts and novels, and in exchange, Ambrose makes the effort to learn how to be charistmatic and good and pristine. Few know about his mother, and when Ambrose meets his uncles, his aunts, his grandparents, their scarcely mention her. It is terrifying, really, how easily people are wiped from existence, just that fast.

III. Cunningham buys him his education, and from that education stems advancement. Ambrose learns, grows, works, writes, becomes a professor first of Roman history, Egyptian history soon to follow, and with every piece he publishes or collaborates on, his fame only increases. At twenty-seven he is offered an observational position on an expedition to old Roman ruins in an effort to unearth hidden treasures, and he accepts without so much as a second thought. William accompanies him for these first few journeys, although his younger brother discovers he does not quite have the taste for it. Ambrose, on the other hand, is ravenous. Forget writing; he’d much rather dig as far his own two hands will take him. The expedition returns successfully, and the pieces of old art and sword pommels are hung up in a museum, displayed for and lauded by the wealthy. Ambrose develops an appetite. He funds and embarks on another expedition, this time to the Valley of the Kings, and does not return empty-handed. He is soon sponsored by the British Archaeological Association, and archaeology becomes his life. He returns to London after every trip with some sort of piece or tale, develops a reputation as an adventurer. The airy and stiff-backed Shaws of old are buried by Ambrose Shaw: charming, handsome, daring Adventurer of the world.

IV. The glory days are by far the best. His renown grows insurmountable, the height of mountains. Most turn their gaze from his more unsavory qualities -- his temper, his ever-present status as a bachelor, his sharp tongue and tendency to remark on ugly qualities in others -- in favor of the gleaming, the gold. The stories he tells, the shape of his frame, what he gives away, the parties he hosts. For each successful expedition it is nearly a guarantee that Ambrose Shaw will return and provide nectar of the gods alongside decent entertainment, and worse still, he’s good at that too. No one can touch him, even when he wants to, and he’d like to keep it that way. Over the years William appears on his doorstep, pleads with him to give it a rest (you’ll run yourself into the ground, Ambrose), but Ambrose ignores him in favor of emeralds in the tombs of dead queens and kings, blades polished until they’re silver anew. He doesn’t even attend Cunningham’s funeral, when the old man dies -- he’s on his second world tour by that time, and there’s not much point in turning a ship around for a dead man without much to him, is there?

V. It should be obvious by now that a fall always accompanies pride, and with Ambrose, his fall takes the shape of a dog-headed sculpture, painted all black, with eyes that shine like rubies in spite of the fact it lacks gems. Tucking it away without thought had been foolish, and putting it on display is worse, but it is put up in a glass case and he lays his head down on the pillow without nary a thought to his deeds. And then the restlessness comes. At first, it’s subtle. Sleep avoids him. He takes to long night walks. And then his body aches. He’s not old, necessarily, but the pains which plague him cannot be soothed even by the strongest of opium. He takes to keeping his hair down -- pulling it back reveals the strands easily pulled from his skull. And then what can only be described as moments of madness. He is always awoken from slumber by the hot breath of a hound on his face, gleaming white teeth in the dark, pink tongue lolling, its claws digging into his chest. It trails after him, from room to room, building to building, place to place. He shuts himself up in his apartments, stops hosting guests and holding parties, but becoming a glorified recluse only makes it worse. This hellhound is an awful fact of life, and in his ear it whispers every mistake he’s made, every foolish thing he’s ever said, every missed opportunity for glory. It haunts him,

PLOT POINTS

I’M THE BEAST / RATTLING THE CAGE, ASKING FOR SLAUGHTER. Why would an archeologist go to a place devoid of history? And ah, there’s the rub. Why would a man who’s dedicated his entire life to keeping his head bowed towards the dirt, always digging, suddenly see fit to turn his gaze towards the sky? Rebirth, renewal, repentance. I’d love to explore (through his relationships with other characters and his developing relationship with himself) the parallels between the man Ambrose so obviously was with the man he is now.

Can others see the corpse he’s unwillingly dragging behind him? Can they see through the flecks of gold as easily as he can to the dirt underneath? I’m sure it shines through, every once in a while. He’s not always unpleasant to be around, even if he more or less shambles around like a dead man walking. I’d like to see if there’s something underneath the horror he’s encased himself in, or if the charismatic and charming Ambrose Shaw is well-and-truly-dead. He feels like a beast walking in human skin, otherworldly in his not-so-subtle bouts of madness, like he cannot control his own body in a way that means anything. Do others see this, and if so, do they confront it, or do they turn their heads?

I SEEM TO BE BUSY TEARING DOWN WHAT I WAS. I’d love for Ambrose to meet with others who have never heard of him. I know that sounds a little silly, but he craves a world in which he has not shared every piece of himself, a world in which there is no Ambrose Shaw, the archeologist of great renown, and instead… Ambrose Shaw, the man. Relationships of any kind — antagonistic, friendly, romantic — they all feel beyond him now, and I can see him clinging to any person who might see him for what he is beyond his reputation, might go so far as to say they’ll be the only ones keeping him even remotely sane.

On the flip side of this, I’d love for Ambrose to interact with characters who have similar burdens. Sometimes the truths of guilt and grief aren’t genuinely opened to you until you’ve shared them with others, and up until now, he’s found himself silenced, biting down on his own tongue.

WHAT YOU CAN’T GIVE AWAY YOU MUST CARRY WITH YOU. I think that Ambrose almost certainly has lessons he could impart upon less-experienced crewmen and guests, with stars in their eyes and metal in their mouths, searching for a taste of adventure. It might be why some of them boarded The Promethean in the first place. The unfortunate reality is that Ambrose wholly believes the adventure he once adored to be something ugly, beast-like, a journey which warps and changes you beyond recognition.

I’d like to see him impart some of his stories and lessons upon those willing to listen to what he has to say; he used to love hosting, after all, even if now he hates it when someone so much as breathes the same air as he. It might take some time, some thawing of the ice in his middle, but I think he’d share eventually.

TO FEEL ANYTHING DERANGES YOU. What does Ambrose see on the back of his lids, when he closes his eyes? Is it a place, a person, a beast, a being? There’s no doubt in my mind that the further along The Promethean’s journey extends, the deeper Ambrose is going to sink into despair, and until he finds a place he cannot dig into with his two bare hands, he will be haunted. He’d boarded the ship in an effort to run from his ghosts, only to discover they'd trailed after him, nipping at his heels like a great black dog. He is unsure of his end, and if he’s to meet it sooner rather than later, but I’d like to explore his willingness to meet it. Would he accept death, if it meant escaping what shows itself to him in his sleep, even if it meant hellfire?

CONNECTIONS*

*These are purposefully vague, and by no means set in stone. I’m absolutely willing to adjust accordingly with whatever plots and relationships The Marked may have had beforehand! I did one for every skeleton, in hopes of providing a jumping-off point for plotting! If you’re looking for your character, CTRL+F and type in their skeleton title!

I. THE VETERAN: They are similarly haunted, even if the shape their ghosts take the form of is different by a wide margin. Their suffering does not appear to be quite so physical, in Ambrose’s eyes, although he recognizes their stiff-legged gait and paranoid gaze as well as he recognizes his own. I could see the two of them growing close, in the fleeting way that friendships through trauma and regret are forged.

II. THE DOE-HEARTED: In her, Ambrose sees the faces of his own family. His brother tried to sway him from his path, time and time again, and he ignored him in favor of grit beneath his nails and the taste of glory. He wants to tell her there might be no hope at all: once a man is swayed towards the path of hubris, it’s difficult to pull him off of it, and if you do manage, the consequences are often dire.

III. THE IDOL: In them, there is the spirit of expedition, the same spirit he’d harnessed in his youth to carry him far and wide. Their fire is by no means unfamiliar, although they have a different flavor than the usual doe-eyed naivete he encounters from men and women too young. They carry a ghost in the shape of their superior with them, and Ambrose can’t help but feel a streak of pity for them, the same pity he holds for himself.

IV. THE CAPTAIN: Pride makes men cruel, angry, ugly, and so does ambition. It’s… odd, this need to shake them by their shoulders and tell them they’re being a fool, but it’s there nonetheless. He doubts he’ll ever work up the courage, but if there were ever a mirror-image of his old self atop The Promethean, Ambrose fears it takes shape in the form of The Captain.

V. THE SCION: He circles The Scion like a bird of prey because he knows of nothing else to do. They were both caught in the throes of London’s glory, both caught up in the pride that comes from being something. But The Scion was kind-hearted, even if they now find themselves setting it aside, where Ambrose certainly wasn’t. He was nasty, cruel-mouthed and sharp-tongued, basked too much in his glory to bother extending his reach to the common people he once worked alongside. His ghosts and his guilt make him similarly ugly, and I’d like to explore if this is any different from the implied connection he and The Scion had beforehand, if their interactions were surface-level or went beyond that.

VI. THE SHADOW: A wolf is a wolf is a wolf, and in them, Ambrose sees hunger that stems neither of eagerness or inexperience. Their hunger is borne from desperation, and he’d be lying if he said that didn’t unsettle him. He, too, has donned sheep’s clothing time-and-time again, lied and cheated and stole to get his hands on the fingerbones of corpses and through the doors of old tombs. He used to be just as hungry, but now his belly has been slit, filled with stones, and any appetite he once had is gone… but The Shadow might reawaken old cravings.

VII. THE IDOL: In them he sees exactly the sort of thing he would have been digging for. Grief, sorrow, and ambition forged into one being, coated in gold and perfect to be put up in a museum. It makes sense, then, given his pretenses, that he would do his best to keep his distance, at the cost of several potentially awkward interactions.

VIII. THE CLAIRVOYANT: They see the thing that hangs around Ambrose’s head. They see the great, hulking wolfhound he has become, alongside the pale imitation of himself that lurks in his shadow. Make no mistake: he may be more terrified than they are, fears answers as much as he seeks them. He dances around the confrontation, skirts around the truth, knows it will find him eventually, knowing they might be the one to bring it.

VIX. THE NOBLE: Their voice refused to harmonize in much the same way his did. They have probably encountered each other, at some point or another, and it seems to be some cruel joke, the way he cannot escape from the very people he once used to entertain. He tries to weave them stories, in the way that he used to, but the words never seem to fit the right way in his mouth.

X. THE COMMANDER: Enough of humility, they declare, and Ambrose wants to tell them he’ll trade his pride for their humility, but he’s seen their silent companion called insecurity dog after as many as twenty men, men he’s dragged around on expeditions and men he’s dug up from graves. Most kings die from insecurity, from a want to be something bigger themselves. Ambrose himself is in the process of decay; he can’t help but wonder if The Commander might follow suit.

XI. THE EMPRESARIO: In them he sees his old self, and when they share the same space, it’s something like a light trying to spark on in the dark. Their ambition is familiar, as is their eagerness to forge a new path ahead. He, himself, had been much the same, in his fleet-footed days as a professor, and he seems to mirror their attitudes and somehow encourage them with ease even with the warning tugging at his tongue, begging to fall from his lips.

XII. THE ROMANTIC: If their brother is a soothsayer, then they themselves are just the opposite. Ambrose takes an admitted comfort to the fact they seem to denounce their sibling at every possible turn, if only because it means there’s a chance his affliction (ghosts, always ghosts) are just… figments of his imagination, lies he tells himself.

XIII. THE LOVER: Beauty is nothing without dread. If history has taught Ambrose anything, it is to fear those who are beautiful above all else, and in that vein, the ghost at his ear whispers to fear The Lover, who has clever eyes and a clever heart. Were he his old self, he thinks he could easily go toe-to-toe with them, but he finds himself older, weary, less capable, and so he holds his tongue.

XIV. THE ENIGMA: He would have trusted them on an expedition in a heartbeat, there’s no doubt about that. They’ve certainly got capable enough hands to do well in a career of bloodshed for a little bit of kingdom. He feels compelled to trust them now, might share a piece of himself here and there, were they willing to let him do so, although he heels more often than he howls.

XV. THE PURSER: They value money the same way he once valued glory, and frankly, that might be all there is to it. By default these days he’s cautious around those who make him think too much of himself, and as someone who vaulted similarly from the slums of London to a position of power, he is waiting for them to meet their Icarian downfall in the same way he did.

XVI. THE DOCTOR: Opium addiction is not uncommon among men in Ambrose’s old circles, and it’s not unfamiliar to him. In fact, these days it’s the only thing keeping Ambrose afloat. I’m not totally sure as to whether or not it’s accessible, but if The Doctor will provide the one thing… that wins him a few sacred minutes of sleep? He’ll be certain to make himself familiar.

XVII. THE CHRONICLER: Theirs is the pursuit of truth, and there’s no doubt in my mind that at some point or another at the height of his fame, they published something unsavory about Ambrose’s endeavors. Something ugly about the way he relished in digging for the dead. He doesn’t much like them, I figure, and he’d rather avoid them than he would hold a conversation, but… some things are just unavoidable, aren’t they?

XVIII. THE STOWAWAY: When given a choice, Ambrose chose to claw and climb his way to the top, at the cost of his relationship with his mentor, his old friend, his colleagues. He had once been nothing, and given the chance to be something, there was no hesitation at all. He understands them, but once again cannot put words to his understanding. They are lost on him, as most things these days are.

XIX. THE SOCIALITE: He entertained them and their family, once or twice. In fact, it might have been the case there was something between them, every blue moon, when hunger of a different kind struck. But the man he used to be and the man he is now are different creatures, and whatever capacity in which they knew each other has surely changed as a result.

XX. THE SONGBIRD: He’d enjoyed their singing, at one time, when he’d stood at the peak of London’s mountains, but a lark is still a lark, and even the most beautiful of songs can sound sour to the wrong ears. Their fall from grace seems to mirror Ambrose’s, however, and the notion makes him uncomfortable.

XXI. THE HARUSPEX: Regret tinges each and every one of his interactions with The Haruspex, no matter how much he wishes it were otherwise. He might be an old dog, but he is a dog with teeth, and The Haruspex reminds him of a whelp that doesn’t know any better. He wishes he could guide them towards a prosperous future in the way he used to guide his students, but his hostility is now reflex, and he doesn’t know how much it’s going to take to shake them off before he outright tears their throat from the rest of them so they’ll stop yapping.

XXII. THE CHAPLAIN: Faith has no power over terror, but he is willing to try, for the sake of achieving the silence he so desperately yearns for. He will pray, repent, confess, do whatever it takes, but there’s something that wonders in the back of his head if The Chaplain can see through this facsimile of worship as easily as he does.

XXIII. THE WILDCARD: It’s a true tragedy to watch someone who is never wrong make mistakes, but Ambrose keeps an eye from a distance anyways. He could attempt to warn them, if he chose to. He does not, and the reasoning for why that is is unbeknownst to him.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Governess as Heroine

NOTE: Illustrations and gifs are not mine.

“May we read the selected works of Edgar Allan Poe please? I’ll be ever so good!”

“It’s 6pm. I get off at 8. Yeah. Mom and Dad will deal with the nightmares.”

It's a staple of Victorian life and nowadays a job title that implies magical shenanigans will follow—the governess. The 1851 England Census listed a whopping 25,000 women employed as governesses, women hired to teach the children of a household and see to their educational and moral needs, not to be confused with a nanny or nurse, who handled babies. One of the only ways a woman could support herself in Victorian times, real-life governesses are a regular who's who of famous people—Marie Curie, Mary Wollstonecraft, and all three Bronte sisters (Emily, Charlotte, and Anne).

Public schools and the ever-increasing demands of education have almost made the in-home governess obsolete, and yet stories still abound featuring a governess as the main character in every genre from horror to family musical. Why? I started thinking about this, and you know the face I make when the idea for a meta comes along.

The deranged hair, too.

So get ready for another history lesson that looks back at the position of the governess and the impact it has on pop culture.

Not Wanted: Plucky Heroine

Our image of a governess is probably a young woman, attractive, but not in a threatening or overly sexy way, teaching three or four precocious Victorian children in a cozy school room, bringing some whimsy into their otherwise repressed lives.

We know now that the Victorians weren't quite as stuffy as they presented themselves as (someday I will do a Top 11 Why Victorians Were Messed Up list), but they really liked acting like they had no more pressing obligations than letter-writing or, if they were feeling athletic, fox-hunting. I mean, these were people that hosted parties where unwrapping an honest-to-god mummy was the main event. They were not about hard labor in the slightest. Naturally, just as the lady of the house was not expected to do the cooking or the cleaning, she was not expected to take it upon herself to educate her own children. The family would therefore have to hire out, looking for an unmarried woman to educate the girls and the small boys (most boys went to a boarding school around 8).

Governess: You two! Go to the schoolroom and let your mother take her snuff in peace!

Mom: You’re hired!

How it would work is that mom and dad would put an advertisement in the newspaper to specialist employment agencies and girls schools. The governess would be expected to teach the three Rs of reading, writing, and arithmetic (and you have already failed as an applicant if you put “reading, riting, and rithmetic” on your application), as well as the “accomplishments,” which were the arts like foreign languages, painting (girls on watercolors only, oil's too manly), and the musical instruments of either the piano or the guitar because girls craning their necks or blowing into things is just a little too unseemly. They would also cover a little history and “use of globes” (what I am presuming is very rudimentary geography). A governess also had to set the moral example to the children since she would spend the most time with them. She had to share the same religious beliefs as the family, so hiring a Catholic governess in England at the time was pretty much out of the question. Also, it was an unwritten rule that you should hire a “plain” girl, lest the young men of the household become interested in slumming it.

“This sounds snooty. Why would anyone do this?”

Well, women didn't have a lot of choices in the early 19th century. The Napoleonic Wars had rendered Europe economically unstable, and that's just bad news for the middle class. A boy could quit school at 15 and go into a trade without upsetting the family since it was always assumed he could earn whatever they had spent on his education and his family didn't have to support him. A girl, though, could really only go into teaching or get married if she didn't want to be a burden to her parents. Since being a governess meant you lived in somebody else's house and ate food you didn't have to buy or prepare yourself, that was a lot better than taking a hit to your dignity and becoming a laundress.

If you met all these requirements, had nothing in your background that would make you seem to be anything less than a pillar of piety, and the family liked you, you would be hired on to teach their kids and follow their household's rules.

Sometimes that included going along with your Henry VIII delusions.

Constant OTJ Training

So now you're a governess, and you're going to learn pretty quickly that you're in for a lonely life with only rich people's kids for company. If you've ever watched the E! Entertainment Channel, you know where I'm going with this. Hint: you're not in for a lot of stimulating conversation and valid friendships.

Because most governesses came from middle class backgrounds in which they were educated, they were considered higher than most of the other service staff in the house. Cooks and maids were told to be deferential to the governesses, as well as the male equivalent, the tutor. And yet, you also weren't part of the family. You teach and entertain the kids all day long, but you don't get to sit down with them for dinner, for example.

“So who do you eat with?”

The mice in your school room, gentle reader. The mice in your school room. Depending on what genre of fiction you are in, you can make these mice your friends and sing to them about hoping for better days, or you can follow one up to the attic and find a dead body. Yes, the school room usually doubled as a sitting room for the governess, meaning that's where she was to hang out in the evenings after hours.

Naturally, this kind of lifestyle doesn't lend itself to forming relationships, at least not with adults.

“Couldn't you just invite the governess next door over for recess or something? Play date?”

Maybe, but if you were on a nice estate, the next-door neighbor was probably half a mile away or more, and if you are watching a lot of kids, you might need the carriage, which the dad has taken into town to talk with other dads about business and how silly ethnic people are while sipping brandy, so that's out. If the family had a party, you were not invited to attend since it was your job to keep the kids in line. Worst of all, even if the family was outwardly nice to you, you were being watched like a hawk.

Lady McHighpants: (offscreen) Sir McHighpants! Miss Drab is crying at the pianoforte because no one wanted to participate in music time! Shall I have the lash to whip her hands for displaying such vulgar emotions in public?

Sir McHighpants: (offscreen muttering) Business things, business things, business things...

Remember, sexual harassment awareness was not a thing, and you're in a very Madonna/Whore society where you need to live up to men's expectations of a woman being pure and saintly at all times. A book out there called Letters to a Young Governess instructed women on how to behave in order to keep their jobs and included this little gem:

“…if there are young men in the family where you reside, remember that your carriage will generally govern theirs; they will not presume, if you are discreet and unpretending.”

What this means is that if they made your life miserable, if they made personal remarks and you retaliated in any way, if they groped you, if they put you in a compromising position in any way, it was your fault. And if you were fired for this, you wouldn't get a job elsewhere because now you're a harlot. Anne Bronte entered the world of the governess in 1839 and eventually wrote an entire novel about her mistreatment in the field. Agnes Grey depicts children who torture animals, lie, steal, and are generally unruly. The parents blame the governess, of course, as she has not established control. On top of this is the wretched loneliness and lack of financial success. Anne Bronte ended up never being a governess anywhere longer than five or six weeks as a result. Things only got worse as she found a position for a male friend as a tutor who eventually had an affair with the lady of the house. That went about as well as you would think, and the poor guy became a drunk.

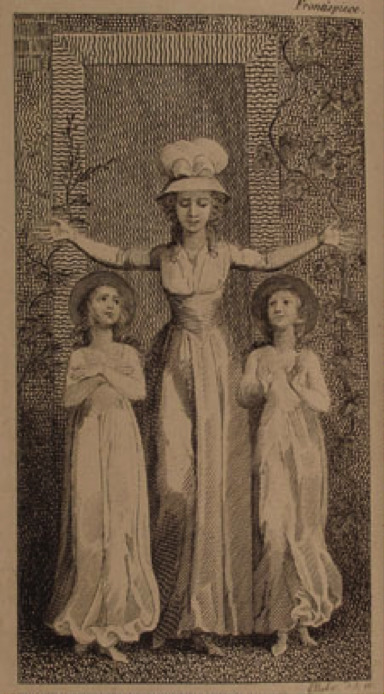

Original Stories From Real Life was a 1791 children's book by Mary Wollstonecraft about two girls and their fictional governess Mrs. Mason. It is rare in that it champions the role of the governess. Mary and Caroline, the two sisters, are orphaned and left to their governess, who slowly rids them of all their faults, the lesson being that proper education and care can create the balance between logic and emotions necessary for children to become rational, charitable adults. It's as dry as it sounds, but William Blake did the illustrations, if that helps.

Note this governess isn't the dark prude in the other paintings, but rather more like an angel, with her two devoted disciples on either side revering her.

“Sure they aren't just coveting that really sweet bonnet?”

I'm sure. Of course, this was 1791, though, and Mary Wollstonecraft was kind of a controversial figure, what with wanting women to be seen as equal to men and all. By the 1830s and on, governesses were painted in shadow, wearing drab, mournful clothing, and sort of being the buzzkill.

So it was a low-paying, tedious job that was mentally taxing and isolating, not to mention thankless.

When a governess' services were no longer required, she could stay on and be hired by one of the girls as a companion (read: ladies maid) or find another family. The loneliness of the job continued into middle age, however, due to most of the men a governess would come into contact with were of the upper class and wouldn't be interested in a woman considered beneath their class. So marrying out of the job was rare. Also, since it was low-paying and required a few moves, many were impoverished by the time they reached middle age, the Governesses Benevolent Institution set up in 1841 to at least ensure these women got a pension.

Jane Eyre and a Rather Angry Fantasy

Rochester: Is this what existence is, Jane?

Jane: That’s the dog, sir.

The most famous fictional governess may very well be Jane Eyre, the titular heroine of Charlotte Bronte's 1847 classic. Jane Eyre could be its own college course, so it will be a challenge for me to keep it concise and applicable to our topic. The basic plot is that Jane grows up in a school from hell and instills in her two conflicting longings for kinship and independence (she's a passionate, thoughtful type). Can she gain purpose and love without sacrificing her integrity and who she is at her core? Thornfield Hall may provide the answer as she becomes a governess to Edward Rochester's French ward Adele. Rochester is a little weird—okay, he's very weird—but he falls in love with Jane, she falls for him, and that's only about halfway through the book. I can't tell you the big twist or how it's resolved, but the whole thing is very Gothic and you've got disembodied voices on the moors, beds on fire, out-of-nowhere family members—the whole thing's an intellectual trip.

Okay, now, first of all, Jane Eyre received very mixed reviews from both men and women. Those who hated it despised the idea of Jane not fitting the mold of the Victorian heroine. Most heroines in the time period were completely self-sacrificing and passive, being the moral inspiration for the rest of their family members and basically being beautiful, sweet angels rather than characters. If your heroine was smart and capable, she was also most likely an old maid, like Marion in The Woman in White. If the heroine had any sexual side at all, she was presented as a tragic figure like Nancy in Oliver Twist or Tess in Tess of the D'Ubervilles.

Jane was a more well-rounded character, very headstrong and independent, a firm believer that women should not be forced into the domestic life; this is fitting since Charlotte Bronte hated being a governess. But Jane also craves companionship. She is “plain and little,” a stark contrast from the unbelievably beautiful heroines who would always wind up just a wife, usually to a man not worthy of her. Jane, however, wants an equal, someone who will love her for who she is rather than what society has prescribed them to view her as.

Rochester: I've been standing in this position for hours waiting for you to come by.

Jane: I work here. And live here.

Rochester: Ah, Jane. There's that wood sprite's wit I so love. (seriously, read the book. He says things like this)

From a governess' perspective, this is both a fantasy and also perhaps a cautionary tale. While Jane is happy at Thornfield Hall and rather lucky to have a friend in Mrs. Fairfax, a well-behaved kid in Adele, and an employer that, well, doesn't think she sucks, she feels something is missing. She and Rochester are intellectual equals, but her low income and inability to properly socialize with the other women who visit keeps her at a lower status. She has to actually ask for money to be able to travel to visit her own family (even though they're assholes and she's only going out of obligation), and, since she is reserved about this kind of thing, Rochester sort of one-ups her whenever he can to get some kind of rise out of her, to include dressing up like an old gypsy woman at his own party. If you're like me, that's when he stopped being fun and a few red flags went up. So while Jane has meaningful relationships, she knows deep down she still isn't being all she can be.

I say it's a fantasy also, because, well, remember what I said everyone was afraid governesses would do with the men in the house?

Reenactment

The idea of your male boss falling in love with you might be flattering, hot, and an easy way to worm your way into high society if he's a widower, but no one would turn a blind eye to this kind of thing. Marriage was big news, especially when it came to the upper crust. There would be no way a rich gentleman could marry a governess and not cause a scandal.

“It's not exactly smooth sailing in the book, what with uninvited guests and what's in the attic.”

Well, Jane also discovers that having only independence and moral superiority is no life for her, either, as it deprives her of love and passion. Between a rock and a hard place, am I right? If you hooked up with a man in the household, odds are he was just using you, would brag to his friends, his parents/wife would find out, and then you'd be kicked out with no references or nest egg for these rainy-day occasions.

Jane Eyre was written at a time when a lot of what was considered common knowledge was seriously being questioned. Were women really better suited for the domestic stuff because of biology? Could the bumps on your head really give insight to your inner character? Are crazy people actually sick and in need of help? And, should we really be treating our governesses like crap when they have already suffered so much?

“Being a Governess Sucks” Lit

As people began valuing education more, the role of the governess changed from Debbie Downer to just an unfortunate turn of events for your average young woman. Little Women, Emma, and Vanity Fair all have characters who either hate being a governess or hate the idea of needing to become one. The latter, in fact, is kind of a humorous take on every respectable aristocrat's worst nightmare of a bitch in governess' clothing swooping in and just taking over. Becky Sharp, you magnificent bastard! I've read your book!

In 1898, Henry James decided that the loneliness and potential powerlessness a governess could have would be an excellent fit for a different genre of literature—horror. “The Turn of the Screw” is one of the best novellas EVER and has been adapted into one of the best horror movies period, The Innocents. This governess doesn't even get a name, and we don't even get a full picture of what's going on since this is one of those frame stories where someone else is narrating to us what happened to someone else. Is this a case of an unreliable narrator? Is the governess cuckoo for Cocoa Puffs? Are the kids possessed? Are the kids just clever little shits? We don't know!

The story is that a governess has been hired to care for a man's nephew and niece, Miles and Flora, the former having just been expelled from school for talking to the other boys about some very inappropriate things. The governess learns that their former governess and the gardener had a relationship, were jerks, spent a lot of time with the kids, and are both dead. The kids start acting weirder, the governess starts acting paranoid, and I can't even tell you the strangest stuff because that would be giving away spoilers.

You ever watch an old movie and think the set would be the perfect haunted house? And then come to find out it actually MIGHT be a haunted house? Welcome to The Innocents, folks. Popcorn and adult diapers both strongly recommended.

The film version spells things out just a little bit more than the story, but it in no way gives the viewer a clear answer that explains what is happening, if this is a haunting, a possession, or people losing their minds. Either way, the governess (played by Deborah Kerr, who we will also talk about later) is in way over her head here. That's the thing. Somewhere along the line, men decided that two things were incredibly easy—house cleaning and child care, and if you've ever had to do either, you know how wrong that is. But no, from the Victorian period on, there have been slogans for newfangled appliances being “So easy a woman can do it,” moms doing chores in their pearls, and cartoon animals helping out with dishes and sewing. Somewhere along the line, someone decided that people who look after children can work long hours and be given only the thinnest shred of authority, and yet pay them very little for it. This woman has no resources. She has an illiterate servant who can give her back story, but that's about it, the uncle she was attracted to at the beginning won't answer her letters asking for advice, and there aren't that many neighbors around. And when kids decide they're not going to listen to you, they're not going to listen to you.

One has to wonder if the story would be a little more clear-cut if it wasn't a governess in the position. If it was someone with a job that usually inspired images of competence and intelligence, like a doctor, would we be more inclined to think the events were real and not just someone going crazy?

“Um no, Deborah Kerr was a little off her rocker before even showing up to the house.”

Very true. The ambiguity is tantalizingly frustrating, and the movie just adds so much atmosphere that it's impossible not to watch it while on the edge of your seat. I don't think I'm spoiling anything, but here is an image of her seeing one of the supposed ghosts:

The black and white doesn't diminish the terror at all. Look how ambiguous and shadowy that looks! And there is this really neat scene where Flora insists she doesn't see the woman all in black staring them down across a field...

“It's governess vs. governess!”

That's another thing to touch on. Miss Jessel, the deceased governess, is implied in a few places to have taken part in things with the kids present that kids really shouldn't be present for, if you get my drift. Was she as depraved in life as she's purported to have been? Or was this a lonely, desperate woman who either sought out companionship or was forced/manipulated into something? How much do the kids actually know? Because they talk and carry themselves like little adults, let me tell you. You will not find creepier kids who do so little to come across as creepy. Any other scary-movie child seems to be putting an effort into it whereas it just comes that naturally to these two.

So this is kind of a worst-case scenario for the life of a governess?

“She gets plagued by ghosts???”

No, she has children with issues that extend well outside her expertise, has no support system to help her cope with that or help the children at all, and ends up suffering the consequences of said issue worse than anyone else. If Anne Bronte had little psychopath kids in her care, then others did, too, and if the parents wouldn't do anything and you have no friends to help you, you have one of two choices—quit your job and start worrying about how you will eat, or put up with it until something really bad happens.

Weapons of Magic or Song (Sometimes Both!)

Into the 20th century, people valued education more than ever before and began respecting educators more for it, although female teachers were still seen as intellectually inferior to men since they only taught little kids while men were learned professors. Oh, add another thing to things men think are easy—house cleaning, child care, and teaching little kids the right way to hold a pencil.

There was a resurgence of the governess as a heroine in the late 40s that extended well into the 60s, a time when people wanted more conservative messages and clearly-defined heroes and villains in their stories, but also when people were challenging the establishment. Rodgers and Hammerstein were those people. Their musicals might have some whimsy to them, but they deal with some very real subject matter, like Carousel addressing domestic abuse and South Pacific dealing with racism.

In 1951, they adapted the memoirs of Anna Leonowens into their stage musical The King and I, which became a movie in 1956. The real Anna did indeed go to Siam (now Thailand) to teach King Monkut's 39 wives/concubines and 82 children, keeping a correspondence with Prince Chulalongkorn, the heir to the throne, well into his adult years. However, there probably wasn't as much sexual tension in real life, King Mongkut known to regard Anna as difficult to work with, and since he was known to be a laid-back, nice guy, most Thai people find Yul Brynner's eccentric, temperamental performance offensive.

Once again, this is kind of a fantasy playing out. Anna, in the story, gains some political clout, is yet another governess who has the head male of the household crushing on her, and miraculously gets 82 kids to not only sit still, but participate in musical numbers.

But on the other hand, The King and I deals with culture clash, sexism, and racism. Anna and the King engage in as much sexual tension-laden situations as Jane and Rochester, but his inner conflict with sticking to tradition vs. branching out makes it an impossible relationship. Anna herself is portrayed almost without flaws, the epitome of grace and mental/emotional resolve, very similar to Disney's Belle. The Asian characters, well, most are portrayed sympathetically and the King and the supporting players are three-dimensional characters, so that's pretty progressive for 1951. Again, though, this is kind of an angry fantasy as Anna is influential and gets to go on this amazing adventure, but the women who would ordinarily be her peers are her students, there is a ton of pressure on her as the only representative of Western thought and ideals (that is portrayed as superior in most productions), and she and the King can never really act on what's sizzling between them.

So is this what the life of a governess is, wherever she may go, always stuck in an odd place between progress and repression?

Rodgers and Hammerstein made a governess their main character again in 1959 with a little show of theirs called The Sound of Music, in which yet again a real-life governess' life is slightly fictionalized. Again, a woman is brought in to teach a brood of kids (“only” seven this time, though), clashes with the dad, and ends up a heroine in a oppressive society. It's a little more in-your-face than The King and I, which purposely kept things vague or only in subtext, when your governess is pitted against freakin' NAZIS.

Maria's more free-spirited answer to goose-stepping was doing the Charleston in floral-print

Maria is an interesting character mainly because she's a slightly more somber free spirit type. She could fit right in with Lucy Ricardo or in a Katharine Hepburn screwball comedy, but she has an intensely spiritual side and can be both well-spoken and passionate when sticking up for her beliefs. She can relate to the children so well because she too knows what it's like to feel you're not good enough when you're a vivacious, outgoing person in a restrictive society that demands you be something you're not, and it's this refusal to just shut up and color that attracts Captain von Trapp to her in the first place.

“Where's MY brooding, handsome single dad who will eventually come to learn life lessons from ME?”

Alas, it's a lot more common for women to inspire men morally in fiction than the other way around, and this does seem to be becoming a trope, doesn't it—the governess having a relationship with the dad. It doesn't seem to end well in real life (see Jude Law and a couple of other celebrities), but these movies rarely focus solely on how the governess impacts the children, and she NEVER influences the mother, if there even is one. It's always the dad, and maybe that's just because most of us are suckers for a good romance, but there has to be more to it than that.

Cuz so many single dads out there really dig the top-button, long-sleeved governess apparel. Rrooowr.

Captain von Trapp's back story is that he was a Navy man and a musician in his spare time, but when his wife died and left him with seven kids, he decided no music and more marching would be his parenting style. Maria, who by now has struck up a strong bond with the kids, chides him for not being emotionally available to his kids, and it's when he hears them sing—which she taught them to do—that he realizes she was right. Now, fortunately the musical doesn't drag this out for longer than it has to and the couple will soon have Nazis to worry about, but what is the fantasy here? Did governesses desire marriage, and, if so, did they desire a marriage to their employer?

There's really no way to find out, but I can see it both ways. On the one hand, marriage was a viable way to escape bad situations back in the day. It's similar to the Cinderella situation. You're trapped in a miserable life until a guy with the right resources volunteers to take you away from it. Cinderella doesn't want to go to that ball so badly just because of plot reasons; she's looking for a way out of her terrible family life and has run out of all other options. A governess didn't meet that many men, she didn't have many friends, and if the strongest relationships she formed were with the kids that she was already mothering a lot more than their biological mother was, maybe it's not too much of a leap to assume that, if the dad was single, he might marry her and make her lady of the house so she is doing the same job of nurturing the kids she already loves, but now with the added perks of financial security and adult companionship.

But, then again, I'm certain just as many of these bosses were jerks and there is no way in hell the governess would want anything to do with them. There is that cliché of liking the bad boy so you can be the one that changes him, but...

Governess: Mister Smith, young Master Winthrop had these matches in his pocket.

Mister Smith: Goodness gracious, Miss Governess! How dare you stifle and coddle this young explorer of mine! The other boys will think he's a sissy!

Governess: But what if he burns the house down, sir?

Mister Smith: Then you're fired!

Governess: Mister Smith, young Myrtle was dangling her undergarments in front of the boy next door, and I thought I should bring it to your attention.

Mister Smith: Have you not taught her basic decorum? What books are you giving her? Not too many, I hope! I'm sure she saw you do that. You're the only one she could have learned that from. Her mother hasn't shown me her undergarments for the last six years!

Governess: Mister Smith, I've received a letter from my sister that our mother is on her death bed, my father is now crippled, and the pig ate my brother's hand. Could I have a week's advance on my salary and five days off to see them?

Mister Smith: Good God, Miss Governess! You can't leave at a time like this! Winthrop is a little arsonist and Myrtle's one step away from becoming a whore! We need you!

You see where I'm going with this? I get when the bad boy at the playground pulls your pigtails because he likes you, but even very young governesses would be able to pick up on the fact that the dad just never has her back. There is that stereotype that women like guys who treat them badly, but, come on. If you work for an asshole, you know it.

Not that Captain von Trapp is an asshole. He opposes Nazis, is a veteran, seems to be a decent fellow once he loosens up a little, and led his kids across the Alps so they wouldn't have to be in Hitler Youth programs (not in real life. They just got on a train). But what is it about changing the dad that makes for such a popular story? Certainly there is more going on with Maria than that as she changes the whole household.

One word: power.

Maria may not crave power in the conventional sense, but this is the one way the governess could legitimately wield a ton of power—influencing the family. She already influences the kids. They spend more time with her than with anyone else. But if she can influence the parents and maybe even befriend them, she's really got a good thing going. Jane Eyre doesn't fall for Rochester because he's rich, but rather because he likes having her around! They talk, they bond, they talk about each other's pasts and problems (albeit not all of them, at first). She has adult companionship, a friend. This means she isn't just the lowly governess. She's a valued member of the household, someone people would miss, not because of the services they render, but because of who they are.

Maybe that's why there are so many stories of a governess being able to do magic. Magic is power.

“I thought it was knowledge.”

Pretty sure if you can do magic, you're at an advantage, too. Bedknobs and Broomsticks and the more recent Nanny McPhee feature middle-aged, single women caring for children that aren't theirs, changing the kids' lives for the better, the former actually using her witchcraft to battle Nazis. They just can't get away from all the supernatural tomfoolery, can they? Miss Price, played to perfection by Angela Lansbury, wants to learn magic to help the Allies win World War Two. Talk about influence. Nanny McPhee (Emma Thompson) may have things on a smaller scale, but she plays just as pivotal a role in the lives of the family members she works for, her mantra, “When you need me, but do not want me, then I must stay. When you want me, but no longer need me, I have to go.”

Influence might just be what every governess wished she had more of, and so we come now to the governess of a story that allows her to change the very dynamic of the family she serves.

Originally a children's book series that lasted from 1934 all the way to 1988, it was adapted by the Walt Disney Company into a masterpiece of a film in 1964, and one that can and should be its own meta. It went through development hell, and one of the aspects Saving Mr. Banks got right was the importance and success of the movie hinging not on the character of Mary Poppins saving the children, but saving the father, who is too much of a workaholic to spend quality time with them.

This has kind of been done to death, the dad so wrapped up in his work that his family life is passing him by, but in no other movie I know of is it done so poignantly. Mary Poppins waltzes in with her no-nonsense attitude, basically hires herself, and when she is about to be fired, she actually masterminds a field trip for Mr. Banks to take the kids on that will have nigh-miraculous results.

I'm of the opinion Mary Poppins (and also Bert) is not quite human, but it doesn't really matter. The lesson of learning to take in life's simple joys is illustrated so beautifully in the haunting “Feed the Birds” song, an amazing scene between Bert and Mr. Banks when Bert sort of spells out what Mary Poppins has been doing this whole time, and a gorgeously-filmed sequence when Mr. Banks walks to the bank, expecting to be fired himself, and reflects on all that has happened. It's not really the kids learning life lessons from Mary Poppins, as they're in reality good kids who are just bored and in need of some attention. Mr. Banks is the one who is just a little too set in his ways and can't be bothered to give his own children any warmth. What stops this from being too cutesy or too preachy is Mary Poppins' practical attitude. She's not an ice queen, but a firm, stubborn woman who denies she does anything magical.

But she gives the kids cough syrup that tastes like rum and dates homeless guys.

The governess aspect of Mary Poppins may be the most believable. See, for all my snark, I find it hard to believe that every single governess suffered. Teaching today is underappreciated and underpaid, but people still do it because it is so rewarding. They are shaping lives. They are an adult kids can go to for help and look up to, maybe even emulate. The job of a governess was to nurture young people, and while some kids I'm sure hated their governesses, there had to be some out there who really loved theirs.

The “Let’s Go Fly a Kite” sequence never fails to make me cry because it's the whole point of the movie. As Mary Poppins watches as the happy family goes arm in arm to the park, it's a bittersweet moment, but isn't it also the best-case scenario a governess can hope for? She did what she went there to do—save this family by teaching them to make time for each other. Realistically, she's not part of the joy, but she is responsible for it. It has to be a little sad for a teacher to watch his/her students move on to the next grade, but it is what is supposed to happen. It's a sign he/she has done a good job. The entire scene is so moving because it really brings everything home. Mr. Banks gets his job back along with a promotion, proving you don't have to sacrifice your family to move up the ladder. Mrs. Banks puts her suffragette sash on the kite, literally making it “come out of the closet” and be acknowledged by her family as something she is passionate about. The kids can look forward to outings with their parents and a lot more warmth at home. All of it is done by Mary Poppins without a thank you, or even a goodbye.

That's why I think the governess as a heroine persists and is a popular choice for storytelling. There is a risk-taking aspect to this woman, no matter how prim and proper she may seem, for she is venturing out on her own with a specific purpose, and it's a noble purpose. The people around her in the story change because of her. She is making things happen, things that have to happen for children to mature. She might find love, she might fight off ghosts, but the woman is a hero for encouraging and persevering, all with very little expectation of credit. Just to give you a real-life example as my conclusion, here is a photo of Anne Sullivan with Helen Keller:

0 notes