#reconstrained design

Text

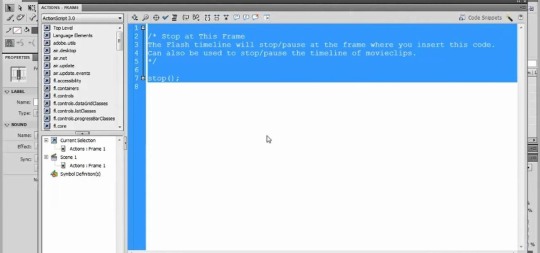

Adobe flash actionscript 3.0 stop function not working

On the first line, type the stop function to stop the pages from cycling through.

Step 9: In the timeline, select the first frame of the Actions layer and hit F9 to bring up the Actions panel.

Repeat this process for the remaining images, incrementing the frame names each time.

Step 8: Right-click on the second frame of the Pictures layer and select "Insert BLANK keyframe." In Properties, change the name of this frame to "pic2." Now drag the next image onto the document, resizing and centering it above the menu.

Step 7: In the timeline, right-click (or command click on a Mac) on the second frame of the Thumbnails layer and select "Insert Frame.".

Move the image to the center of the document above the menu. Resize it in the Properties panel, remembering to click on the chain-link icon to reconstrain the width and height values. In Properties, change the name of this frame to "pic1." Drag the image corresponding with the first menu item onto the stage.

Step 6: From the timeline, select the first frame of the Pictures layer.

In the Properties panel, change the instance name to "button1." Select the next image from the menu and repeat the process, naming it "btn2" and "button2." Continue the process for each menu item. Change the name to "btn1," change the type to "button," and click OK.

Step 5: Select the first image and hit the F8 key on the keyboard.

TIP: Adjust the images' alignment in the row by selecting all of them and choosing the desired options from the Align panel.

Repeat this process for the remaining images so that they are in a row at the bottom of the document. Position the image at the bottom left of the document. In Properties, click on the chain-link icon to unconstrain the width and height values.

Step 4: With the Thumbnails layer selected in the timeline, drag one of the imported images onto the document.

Once you've selected your images, click "Open." You'll see the imported images in the Library panel. You can select multiple pictures by holding down the Control key and clicking multiple images.

Step 3: Import your pictures by going to File, Import, Import to Library.

Starting from the bottom, name the layers: Actions, Thumbnails, and Pictures.

Step 2: From the timeline panel, click the "New Layer" button until you have three layers.

Switch the workspace layout by clicking on the drop-down menu box in the upper left of the top menu bar and selecting "Designer." Change the size and color of the document by adjusting the settings in the "Properties" Panel.

Step 1: In Adobe Flash, select "Flash File (Actionscript 3.0)" from the "Create New" menu.

0 notes

Text

Superlative objects and technological dreams

Thanks for tuning in - it’s been a while.

Since the last post Crap Futures has left the island of Madeira, it seems, for good: Julian to Breda in the Netherlands and James to Paris. Shifting from the vast expanse of the quinta overlooking the open Atlantic to confinement in our small urban apartments under numerous lockdowns may have stymied our ability to write … but finally here we are. The following words emerged from a rejected conference paper (where all good ideas are born) and aim to provide another analysis on the state of the design industry today.

What follows is a (very) potted Western history of the designed object, or more specifically the superlative object - and an argument that the placing of such high cultural value on the object allows the systems and resources behind its realisation (the means) to be largely taken for granted.

This elision gives mainstream design an enormous advantage over alternative approaches, as all the available methods and means - global resources, neo-liberal labour practices, highly sophisticated manufacturing and marketing methods, intricate supply chains and the latest technological advances - can be exploited to achieve the celebrated end. How can more ethical or ecological design processes compete - when only the end product, the superlative object, is valued?

What do these terms mean? Let’s take a closer look.

The superlative object

In Mythologies Roland Barthes introduced the notion of the superlative object through the example of the Citroën DS. Cars, he argues, ‘are almost the exact equivalent of the great Gothic cathedrals: I mean the supreme creation of an era, conceived with passion by unknown artists’. Commenting on the seamless perfection of the vehicle, he compares it to the ‘unbroken metal’ of science-fiction spaceships and even to the smooth and seamless robes worn by Christ. Barthes’ emphatic words anticipate the status objects of today. Seams, he argues, reveal the hand of the (human) maker, therefore suggesting that the DS is beyond human – an immaculate conception.

Our history of the superlative object begins in France during the 19th Century. Redgrave’s Manual of Design from1890 provides a rigorous examination of the superlative objects of the period, tracing their origins back to the establishment of the ‘royal manufactories, the tapestry and furniture works of the Gobelins, Beauvais, and Aubusson ... in these works the most skilled workmen, aided by the most scientific men of the age, executed the designs of the first artists of France’ (p. 4). Redgrave’s manual and the essays of his father that preceded it were largely written in response to the great exhibitions of the mid-19th Century, in London (1851) and Paris (1855). The original intention of the French exhibition was to honour the prototype builders - designers, craftsmen, and workers - through the various displays in the Palais de l’Industrie (Poisson, 2005). Whilst these displays were ‘often products of an impeccable, at times even virtuosic technique, they nevertheless formed part of an occasionally redundant, profoundly eclectic and overabundant decor ... which had been misappropriated in the name of ornament worship’ (p. 4).

This analysis of the superlative object is supported by Redgrave who is even more damning of the French tendency towards the meretricious: ‘the world is still deceived with ornament’, he suggests, ‘and led astray by pretentious display, instead of advancing in the road to real excellence’.

The Arts and Crafts movement emerged from an attempt to reform design and decoration in mid-19th century Britain. It was a reaction to the pretentious displays seen in the great exhibitions of the period. Redgrave insisted that ‘style’ demanded sound construction before ornamentation, and a proper awareness of the quality of materials used. ‘Utility must have precedence over ornamentation' (p. 15).

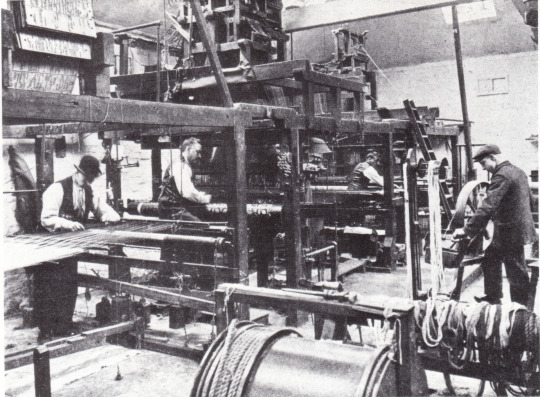

Machines and making

In the late 19th Century debate began to grow about the relationship between designing and making. For some key figures in the Arts and Crafts such as John Ruskin and Walter Crane, the making of an object should happen totally under the hand of the designer, while others (including Morris) believed that mechanisation was not negative in itself, and machines used well could improve the quality of the designed object.

This argument was played out in a discussion between Crane and the early industrial designer Lewis F. Day:

W.C. ... I presume you would admit that a designer is all the better for a first-hand acquaintance with the conditions, necessities and limitations of the work for which he is designing.

L.F.D. Certainly; but it doesn't follow in the least that he should execute his design with his own hand.

W.C. How then would a designer obtain his first-hand acquaintance with a method or material unless he had actually worked out his own design in that method or material?

This was perhaps the last true period when designed means and ends existed in an unbroken continuum; when design was considered as a social justice movement as much as an aesthetic one. The last line from Lewis F. Day is quite remarkable when viewed from today’s perspective - that a designer would do all that he designs.

This brief history will now move across the Atlantic because the version of design developed there during the 1930s, in many ways, represent the true genesis of the version of design that dominates today.

Building on the ideas of the more progressive members of the Arts and Crafts movement, the ex-set designer Norman Bel Geddes described an approach to design that completely incorporated the manufacturing process, advocating that the designer should ‘visit the client’s factory and determine the capacity and limitations of the machines and workers’.

As the century progressed the capacity grew exponentially whilst the limitations of the workers were increasingly bypassed by sophisticated machinery and automation.

Industry and spectacle

Bel Geddes was also one of the pioneers of the influential movement Streamline Moderne. Here he describes the potential elevation of the industrial object to the superlative:

When automobiles, railway cars, airships, steamships or other objects of an industrial nature stimulate you in the same way that you are stimulated when you look at the Parthenon, at the windows of Chartres, at the Moses of Michelangelo, or at the frescoes of Giotto, you will then have every right to speak of them as works of art. Just as surely as the artists of the fourteenth century are remembered by their cathedrals, so will those of the twentieth be remembered for their factories and the products of these factories.

The invention of the internal combustion engine at the beginning of the century had transformed the way Americans moved around, but by the mid-1920s the US car industry had reached saturation point. Alfred Sloan, the boss of General Motors, came up with a plan to keep people buying new cars. He introduced annual cosmetic design changes to convince car owners to buy replacements each year. The cars themselves changed relatively little in their essence, but they looked different.

This created the new role of the consumer - and with it the growth of public relations and advertising. As Bel Geddes suggested in 1932: ‘the artist’s contribution touches upon that most important of all phases - entering into selling the psychological. He appeals to the consumer’s vanity and plays upon his imagination, and gives him something he does not tire of’. Cars became symbols of progress and objects of status. J. G. Ballard provides a wonderful cultural critique on this subject:

youtube

Towards the end of the 20th Century (in The Society of the Spectacle) Guy Debord stated that: ‘in societies dominated by modern conditions of production, life is presented as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has receded into a representation.’

It is impossible, for example, to separate an Apple iPhone from the brand, its marketing, and the global fanfare that surrounds the launch of a new Apple product. This focus on seamless design, on the spectacle, on the superlative object, has (to paraphrase Albert Borgmann), resulted in a dramatic dislocation of ends from means. Highly emotive and susceptible personal value systems, such as a perceived enhancement of status, place an almost total emphasis on the end, allowing the means to be reduced to whatever it takes to facilitate its existence.

Problematic means to superlative ends

We’ll conclude with 5 key examples of problematic means hidden behind the thick facade of the superlative object.

1. The verb to design has become increasingly separated from the verb to make. As a consequence the practice of planning has become reduced to moving shapes around on a screen, whilst the arranging of (physical) elements happens in increasingly complex technical systems. Design is dislocated from making.

youtube

The designers of today’s superlative objects follow both Morris and Bel Geddes’s lead in that they remain obsessively connected to the manufacturing process. However, the complexity and expense of the machines that do the making have grown exponentially.

In a 2012 video (above) showing the manufacturing process of the iPhone 5, Jony Ive states the Apple belief that ‘going to such extreme lengths is the only way that we can deliver this level of quality’. Whilst Apple’s approach clearly leads to the elevated status of their products, the machinery at their disposal gives them an enormous advantage over those with more humble tools.

2. The material elements used in contemporary designed artefacts (e.g. rare earth elements) have become increasingly global and out of reach of the individual.

In this case we can trace the origins of the designer’s use of elements back to the colonial era. Arthur Chandler notes that at the time of the 1855 World’s Fair, ‘the French attitude is a mixture of pure greed and the dawning sense of the “civilizing mission” of France: Africa will supply the raw materials; and in return, France will supply the most precious of all commodities: French civilization’.

Turning again to the iPhone, it comprises 75 of 118 elements from the periodic table (the human body is made up of around 30). In a 2017 article for the Los Angeles Times Brian Merchant described the pulverising of an iPhone and then analysing the resulting dust using mass spectrometry, X-ray fluorescence and infrared analysis. He suggests that to obtain the 100 or so grams of minerals found in a single iPhone, miners around the world have to dig, dynamite, chip and process their way through about 75 pounds of rock on nearly every continent. Very little has changed!

3. The functional purpose of contemporary designed artefacts has become increasingly dependent on global infrastructure systems, thus perpetuating established power structures.

In A History of the Future (2008), Donna Goodman describes how the invention of electricity was instrumental in laying the groundwork for the coming machine age. By the 1940s 90% of American homes were connected to the electricity grid. This in turn led to many new domestic products - all electrically standardised via the sockets they plugged into and all dependent on the infrastructure.

Contemporary products today are reliant on far more complex systems than the electricity grid; for example, the GPS system on mobile phones is owned by the US Government and operated by the United States Air Force. Anything from thermostats (e.g. Nest) to vehicles are increasingly becoming reliant on, and controlled by, connection to the internet. The design of almost all modern products is constrained by the reliance on infrastructure.

4. The aesthetic purpose of contemporary designed artefacts has become deeply entwined with the manipulation of human desires via increasingly sophisticated marketing practices.

This is not a new practice. In 1890 Richard Redgrave likened the French Goods at the 1855 Paris Exhibition to the ‘gilded cakes in the booths of our country fairs, no longer for use, but to attract customers’. In Objects of Desire (1986), Adrian Forty affirms that for a product to be successful it must incorporate the ideas that will make it marketable.

This results in manufacturing goods ‘embodying innumerable myths about the world, myths which in time come to seem as real as the products in which they are embedded’. How then to re-separate the object from its image? Or to see through the image to what it really stands for?

Even the more respectable elements of the media fall prey to design’s sleight of hand - this is from an article in the New York Times in 2016:

‘There has been zero innovation in this market for over 60 years,’ said Mr. Dyson, 68, a billionaire who was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 2006. ... Mr. Dyson, Britain’s best-known living inventor, is the Steve Jobs of domestic appliances. He has built a fortune from making otherwise standard products seem aesthetically desirable ... Dyson said there were 103 engineers involved in the creation of the Supersonic, which included the taming of over 1,010 miles of human hair tresses and 7,000 acoustic tests as teams tackled three core issues: noise, weight and speed. ... As a result, the Supersonic will retail at $399 when it arrives in the United States in September.

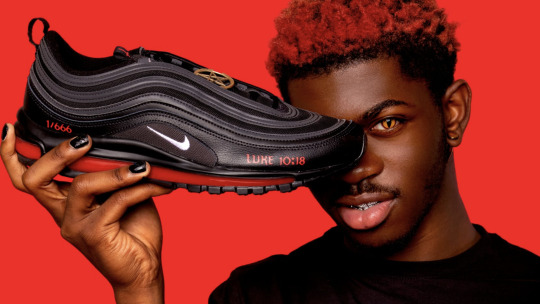

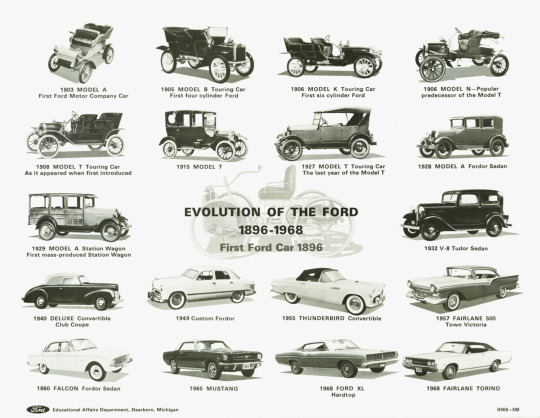

5. The plans for designing contemporary artefacts are typically iterative in nature. This facilitates and maintains the current approach to economic growth via generational products.

We raised the constraint of future nudge in one of our early posts - here’s a slightly updated explanation: According to the economist Robert Heilbroner, ‘All inventions and innovations ... appear essentially incremental, evolutionary. If nature makes no sudden leaps, neither, it would appear, does technology.’ And as a consequence neither do technological products.

This limits the designer to developing only what the current product could realistically evolve into. In reality it is a mechanism, employed by corporations - to maintain lucrative generational economic models, extend the life of production lines, pander to conservative tastes through risk-avoidance, facilitate rapid object obsolescence, and encourage various forms of brand loyalty.

There is nothing to suggest, however, that the decisions made many product generations ago were the ideal ones. Whilst natural organisms cannot be freed from their genealogical lineages, technological artefacts certainly can.

Next post: Towards appropriate means

11 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Reconstrained Design (the book)

We have a new book, a catalogue of sorts, covering certain aspects of our work as the Reconstrained Design Group* over the past couple of years. It’s a handsome object full of nice words and images - some of which you may have seen first on this blog. There is also new material: for example, it features essays on Reconstrained Design by Lucy Suchman and Clive Dilnot. Please send us a message if you’re interested in receiving a copy.

Here is a short piece from the book, ‘DIY Reconstrained’, written by ourselves and Enrique Encinas:

The three words that form the DIY acronym send a clear and empowering message: anyone can do it. You can do it. But do what? What needs to be done? For some, DIY resides in a shed at the back of the garden—the Reader’s Digest manual from the 1970s that tells you how to fix everything from a drainpipe to a typewriter. For others DIY suggests punk rock, a form of expression that requires only minimum skill to achieve satisfying results, and that builds around it an active community, rejecting the passivity of corporate consumerism.

DIY is rational resistance to an irrational consumer culture. Paul Mazur of Lehman Brothers declared in 1927: ‘We must shift America from a needs, to a desires culture.’ Public relations, advertising agencies, and designers answered Mazur’s call with methods appealing not to the rationality of citizens but to the irrational and subconscious drives of consumers. The marketplace boomed as selling bypassed the intellect to interact directly with the emotions. This near complete alteration of perspective puts DIY in a fragile position—impoverished by its more complex appeal, its objects struggle to compete with the hi-gloss culture of brands and fashion. For many consumers, the latest iteration of consumer electronic products exhibit a near sacred aura.

In Mythologies (1957) Roland Barthes describes this elevation of object status through the example of the Citroën DS, the ‘Goddess’—‘a superlative object’. He comments on the seamless perfection of the vehicle, likening it to the ‘unbroken metal’ of science-fiction spaceships and even to the smooth and seamless robes worn by Christ. Seams, he argues, reveal the hand of the (human) maker—methods of assembly and therefore dis-assembly (or fixing). In a sinister shift, this godlike approach to artefacts has become the celebrated norm of product design—think of Apple—where ‘perfection’ means not letting any grubby hands inside the pristine carapace of the technological device, not meddling with divine creation. How can DIY compete with such perfection?

The deskilling of a generation of young people presents another problem for DIY, as schools focus too exclusively on new ways of making such as 3D printing and laser cutting. This has severely limited the scope of what can be made and by whom.

It was in the early 20th century that DIY, the ungenteel inheritor of the Arts and Crafts movement, got its name. Then and now, in the Maker Movement, DIY is viewed as a creative and/or recreational and/or money-saving activity. It is helpful, useful, and fun. It is as straightforward a practice as the end it wants to accomplish. Through a set of accessible premises, ‘shed’-style DIY launches the rational individual into a journey of self discovery and learning—a journey that normally ends when function is met and hence need is no more. As a good citizen, one finds in DIY the sensible alternative to a trip to the store. As a consumer embedded in a culture of desire, however, the workshop presents a real challenge—who has the time, access, or requisite knowledge? As with the Arts and Crafts movement, the Maker Movement risks simply being a mouthpiece for the middle classes, an outlet for those with the disposable time and income to temporarily reject the mainstream attitude towards objects and our interactions with them. So what can be done?

Royal detested this orthodoxy of the intelligent. Visiting his neighbours’ apartments, he would find himself physically repelled by the contours of an award-winning coffee pot, by the well-modulated color schemes, by the good taste and intelligence that, Midas-like, had transformed everything in these apartments into an ideal marriage of function and design. In a sense, these people were the vanguard of a well-to-do and well-educated proletariat of the future, boxed up in these expensive apartments with their elegant furniture, and intelligent sensibilities, and no possibility of escape.

- J.G. Ballard, High-Rise

Consumers have been programmed for sleek, seamless products far too long to accept the standard (non-designed) DIY aesthetic overnight. The desire for award-winning coffee pots (and phones, juicers, hair dryers, etc.) is strong, and for the time being Ballard is most likely right—there is no possibility of escape. This leaves two options: one easy, one very difficult.

The hard route: Adapt consumer desires to a maker aesthetic. Reprogramme people to be less obsessed with brands, or to see value in what is rough, cheap, or practical.

The various gravity batteries described in the Newton Machine project exemplify the approach with their focus on easy making over high-level production, found components over highly-refined, open-source over heavily patented and local materials over globally sourced. This is the first challenge we set in our manifesto—to reverse Mazur’s statement and return to a needs-based culture. But this is a slow-burning, long-term strategy.

The easier route: Adapt the DIY aesthetic to what people want. Introduce a better sense of design that allows maker products to compete with mainstream exemplars of good design such as Apple and Dyson. What would a DIY artefact like if it had the touch of Charles and Ray Eames? Or Dieter Rams? Or Enzo Mari? There aren’t many designed maker objects to be found. The OpenStructures WaterBoiler is one example of how such things could look. Originally designed by Jesse Howard and Thomas Lommée, it was adapted by Unfold, who replaced the PET bottles with a cut-through bottle (see Tord Boontje’s Transglass project for the potential of cut recycled glass) and used a combination of 3D-printed ceramic, off-the-shelf plumbing material and simple folded steel. If more objects like these were produced by the Maker Movement, there might be a chance of shifting consumer habits.

To complement our sometimes utilitarian approach, we are developing more designerly examples of Reconstrained Design addressing the complex notions of desire that drive conspicuous consumption. The Gravity Lamp and Gravity Turntable, for example, aim to provide a more direct challenge to contemporary design, by removing constraints imposed by its relationship to the market. The aim is not only to address stylistic issues but also the problem of making—that the route to ownership should not be constrained by a lack of skills or access to tools. The solution is to build a network of experts, professionals, and craftspeople, essentially decentralising DIY by engaging with the local community, its expertise and its resources. A DIY manual for a product could, for example, be a wiki that shows the constructive steps but also points the way to local cabinet makers or metal shops that will help to build sophisticated elements of a project. This approach would also support the survival of craft knowledge in local communities.

* The Reconstrained Design Group is James Auger, Julian Hanna, Laura Watts, Enrique Encinas, Mohammed Ali, and Parakram Pyakurel

Images:

Citroën DS 19; Enzo Mari by Adriano Alecchi (Mondadori Publishers) - both via Wikimedia Commons.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Careless whispers

In a previous post we mentioned the story of the infamous conflict between King Henry II and Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury, in 12th century England. It’s a familiar story of two powerful and egotistical men clashing over issues of status and pride. After a series of altercations over clerical privilege, Henry finally loses his temper; what he actually said to the assembled courtiers has been lost to history, but the most likely version comes from the biographer-monk Edward Grim, who recorded it as follows:

What miserable drones and traitors have I nourished and brought up in my household, who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born cleric?

Whatever Henry said, four of his knights (Richard le Breton, Reginald FitzUrse, Hugh de Morville, and William de Tracy) interpreted the utterance as a royal command. They rode to the Normandy coast, took ship for England, and confronted the Archbishop. What happened next was described by the aptly named Grim, who was on the scene and actually wounded in the attack:

The wicked knight, fearing lest Becket should be rescued by the people and escape alive, leapt upon him suddenly and wounded this lamb who was sacrificed to God, cutting off the top of the crown which the sacred unction of the chrism had dedicated to God.

More terrible blows followed, and eventually the Archbishop succumbed. Was the king’s statement interpreted correctly? We’ll never know. But we can perhaps read parallels to our own time in the complex motivations and agendas that informed the knights’ collective decision to commit murder.

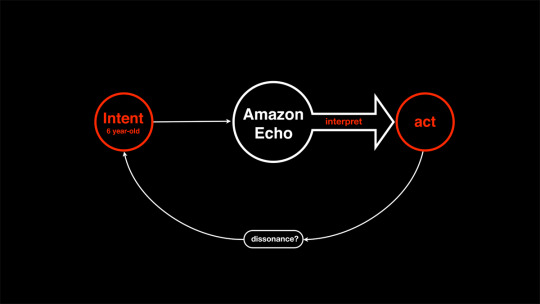

Another story, more recent. This one takes place in Dallas, Texas, where a six-year-old girl asked her family’s Amazon Echo: ‘Alexa, can you play dollhouse with me and get me a dollhouse?’ Alexa promptly complied, ordering a $300 KidKraft Sparkle Mansion doll’s house from one of Amazon’s suppliers. She also ordered (for reasons known only to the internal logic of the system) nearly two kilograms of sugar cookies. The story doesn’t stop there: the following day, when a San Diego news programme reported the story, a number of Echos were roused by the wake word ‘Alexa’ coming from proximate television sets, and they in turn followed the command to also purchase dolls’ houses.

What inspired Alexa to order the biscuits? A flawed system or a very smart one?

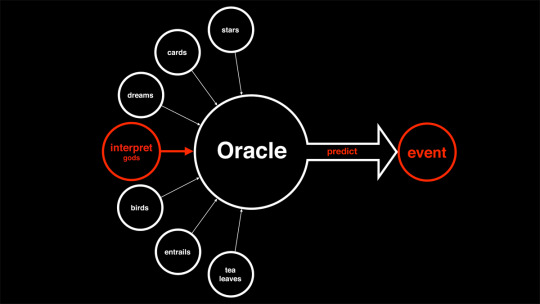

In 560 BC, King Croesus of Lydia set a challenge to the world’s oracles to determine who provided the most accurate prophecies. His emissaries were sent to seven sites to ask the resident oracle what the king was doing at that precise moment. The winner was the Oracle of Delphi, who correctly reported that the king was making a lamb-and-tortoise stew.

Oracles were seen as conduits to the gods, speaking and giving advice on their behalf. Divination came in many other forms: augurers would follow the flight paths of birds (legend has it that the location of Rome was decided through this approach). Haruspices would read the entrails of sacrificed animals. Today, however, reading the future is much less exotic or gruesome, being mostly about data and statistics.

The next story starts back to front. A man walks into a Target outside Minneapolis and demands to see the manager. He’s got a handful of targeted coupons that had been sent to his teenage daughter, and he’s angry. ‘My daughter got this in the mail!’ he said. ‘She’s still in high school, and you’re sending her coupons for baby clothes and cribs? Are you trying to encourage her to get pregnant?’ In fact the daughter actually is pregnant. Target knows it before the girl’s father, thanks to a hunch based on its analysis of online searches and product purchases - in this case a particular lotion often used by pregnant women in the second trimester.

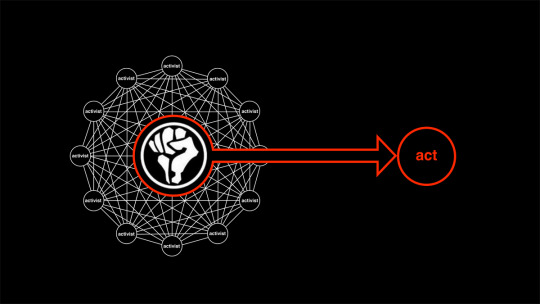

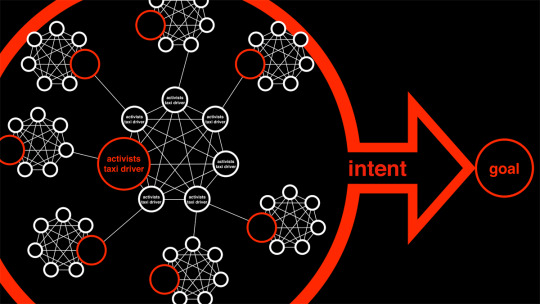

One more story. In happier times for Facebook, the social media giant played a significant - if unevenly distributed and still debated - role in the Arab Spring by facilitating communication between protesters. The April 6 Youth Movement in Egypt, for example, used Facebook to launch a successful call for protests in the aftermath of the Tunisian Revolution that preceded the spread of uprisings across North Africa and the Middle East in 2011-12. Events of the Arab Spring demonstrated that social networks provide a perfect mechanism through which to disseminate information broadly and quickly, as long as you have access to the internet.

So far this is a familiar and well-trodden tale; the more interesting story, however, happened when Arab states began to shut down internet access. Activists in Cairo found the solution in a different kind of social network - not screen-based, but via the city's taxi drivers. The activists realised that if they could direct conversations towards the planned anti-Mubarak gathering on 25 January 2011 in Tahrir Square, taxi drivers might spread the word and the protest would be a success. Initially, the activists tried to talk directly to drivers.

But they soon discovered that due to the highly politicised nature of their subject, conversations would quickly turn into arguments rather than dissemination, and their objective would fail. The solution was found in exploiting the human tendency to gossip. Instead of engaging in direct conversation, the activists allowed the taxi drivers to overhear a mobile phone conversation where they would disclose the details of the protests. The taxi drivers eavesdropped, and believing they had overheard a gossip-worthy secret, they began to spread the message.

‘Technology is making gestures precise and brutal, and thereby human beings.’ - Adorno

In one of our very first posts, The Pleasures of Prediction, we described the daily experience at our local cafe - where the gestures of interaction were not always precise, sometimes brutal (depending on the mood of either ourselves or the people behind the counter), but mostly genial and surprisingly seamless. More recently, our colleague was telling us how his landlady keeps track of the number of bottles of alcohol he consumes each week by counting his recycling - a sort of small island version of a fitness tracker like the Fitbit. ‘She’s not judgemental’, he said. ‘Well … not really.’ Of course surveillance and tracking - mediating, amplifying, interpreting - have always been present in society; in the past they were just more social, or at least more analogue.

These examples raise some big questions, such as: Would you rather be monitored by a human being or a machine? If machine, why? Why don’t we trust humans? For that matter, why don’t we trust ourselves? How have we been shown to be untrustworthy and unable to control our own self-destructive or anti-social impulses? For the past two years we have been collecting stories that relate to the interpretation of information - tracing the shift from human beings to technological mediation as translator and interpreter; who is making important decisions, on whose behalf, and why.

There is certainly precision and brutality in Cambridge Analytica’s use of Facebook data for micro-targeting and psychological profiling. Likewise Amazon Echo, a data-based Trojan horse mediating our personal lives in increasingly precise but also brutal ways. There is a tendency to understand and evaluate technology according to old-fashioned notions of progress: faster, easier, more efficient and so on. But digitisation, the data that it creates, and the vast networks of dissemination also facilitate the augmenting of darker aspects of human behaviour, targeting our deepest vulnerabilities. How we examine the implications, embrace the ethics, and understand the complexity of these systems are some of the fundamental challenges we face.

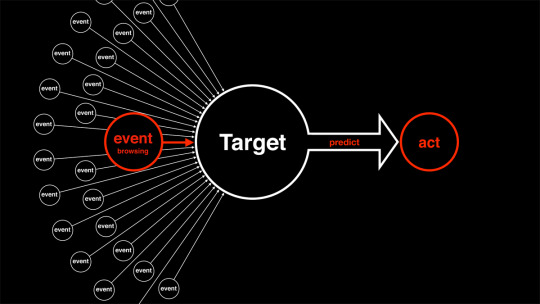

Real Prediction Machines

Shortly before the Echo appeared on the market in 2014, Real Prediction Machines addressed many of the issues Amazon’s new device (and others like it) would raise. The speculative project was developed by James Auger in collaboration with designer Jimmy Loizeau, artist Alan Murray, and Edinburgh University data scientist Ram Ramamoorthy, who at the time was developing predictive modelling systems combined with machine learning to predict when professional athletes might sustain an injury through overtraining.

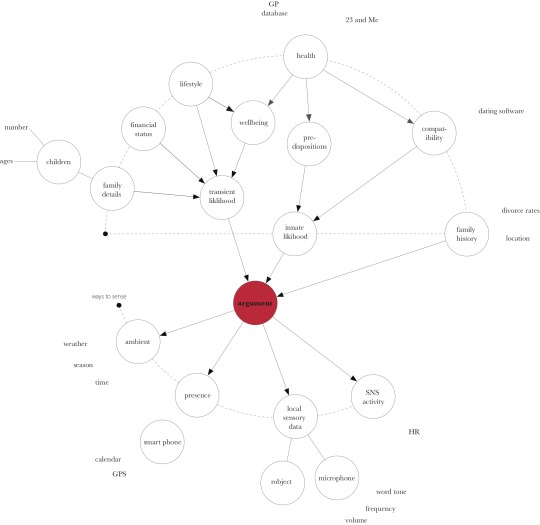

James, Jimmy and Alan began by asking Ram what kind of other things might be predictable through such techniques, such as ‘Will my child become a professional football player’, ‘Will Labour win the next general election’, and ‘Will I suffer a heart attack?’ The words inside the circles of the Bayesian network diagram represent potential variables. In relation to a heart attack they could correspond to something like diet or exercise, the data coming from a supermarket loyalty card, or the accelerometer in your smartphone. Or more finite information such as family history, for example data coming from a genetic testing service like 23andMe.

These variables combine to create a live and ongoing feed into the predictive algorithm. The heart attack example seemed a little too banal due to its obvious connection to wellbeing and the huge growth of data and tracking methods, so the group suggested another question to Ram: Will I have a domestic argument?

The Bayesian network shown above looks similar to the earlier one, but in this instance a microphone was added for live sound input (anticipating the omnipresent Echo). Using machine learning, the system would become better at predicting arguments through the statistical analysis of keywords, tone, and frequency - identifying particular subjects that a couple might commonly fight about.

The output was translated into an object - not an app but something more symbolic, sympathetic. They settled on an ambient device sitting in the background, providing information when you might need it.

The device essentially has three states:

Clockwise means that the argument is moving into the future;

Anti-clockwise means that the argument is approaching, and the slower the rotation the more imminent it is;

When the rotating stops, the argument starts.

Projects like Real Prediction Machines work when it is not completely clear whether the idea is a ‘good’ one or not. Is it too invasive? Is it genuinely helpful? This is how we should think about all potential technologies, but we rarely do.

What happens next? How far away are we from Alexa ordering not biscuits, but a councillor? How much control will we have in the future, and how much do we want to have?

Images:

All diagrams by James Auger; photo of Real Prediction Machines by Sophie Mutevelian.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reconstrained Design

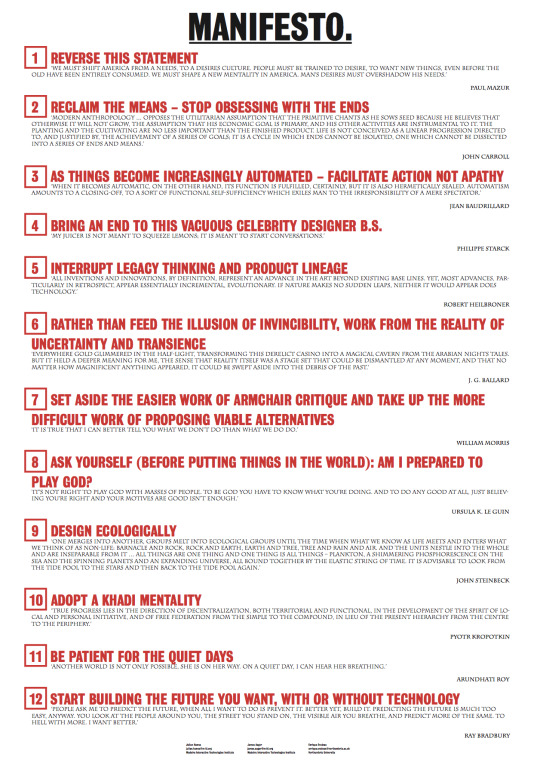

For the record, here is the Vorticism-inspired manifesto poster we brought to the Designing Interactive Systems conference in Edinburgh.

Find the full paper here: http://dis2017.org/provocations-works-in-progress/

Higher res version: https://www.dropbox.com/s/mnmolehr0j1t3gt/MANIFESTO.pdf?dl=0

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Time reconstrained, part 2

In the previous post we got onto the topic of time and energy. We pointed out that in this relatively blink-of-an-eye moment we’re living in—say the last hundred years—some of us enjoy the kind of energy abundance and comfort that no one before us had ever enjoyed and that, at this rate of simultaneous rapid consumption and spiralling environmental degradation, no one after us will either. We also described how, when time is factored in, fossil fuels are actually inefficient and low yield in terms of a time-energy ratio. Now let’s go a bit deeper into that thought: what if we took time seriously in our calculations of energy value and efficiency?

Time is a crucial factor that is often left out of discussions around energy. Traditional fossil fuels, as everyone knows, take millions of years to form and only brief moments to consume. So while they have very high energy densities (i.e. calorific values), drawing a direct comparison between fossil fuels and renewable energy sources can be misleading. Renewable energy sources have much lower energy densities—but they do not deplete in real time, and their formation timescale can be taken as virtually instantaneous.

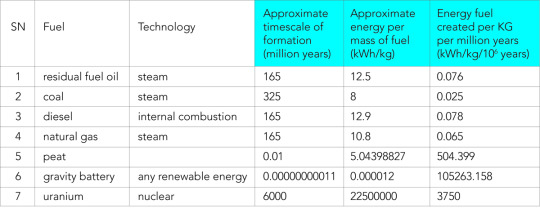

The table and graphs below compare renewable energy sources and traditional fossil fuels in terms of energy per mass of fuel as well as energy fuel created per kilogram per million years. Figure 2 for example shows that if only approximate energy per mass is considered, the energy storage value of a gravity battery using a renewable energy source is negligible compared with the storage value of fossil fuel. However, if the time taken to form energy sources is taken into account, the situation is suddenly reversed: fossil fuel sources become negligible compared to a renewable energy source like the gravity battery (Figure 3). (Thanks to our postdoctoral researcher, Parakram Pyakurel, for crunching the numbers used in these diagrams.)

Fig.1: Comparison between timescale of formation and energy stored

Fig.2: Approximate energy per mass of fuel (kWh/kg) vs. fuel

Fig.3: Energy fuel created per kg per million years (kWh/kg/million years) vs. fuel

Images: James Auger

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Time reconstrained, part 1

We have assumed increasingly over the last five hundred years that nature is merely a supply of ‘raw materials’, and that we may safely possess those materials merely by taking them. This taking, as our technological means have increased, has involved always less reverence or respect, less gratitude, less local knowledge, and less skill. Our methodologies of land use have strayed from our old sympathetic attempts to imitate natural processes, and have come more and more to resemble the methodology of mining.

- Wendell Berry, ‘The Total Economy’ (2000)

The condition in which some of us now live—and have lived for decades—is undeniably a luxurious one, energy-wise, comfort-wise. No one in human history has had what some of us now have; but equally there is a growing sense that if things don’t change neither will anyone have it again—we are rapidly depriving future generations of energy resources and a clean, stable environment, both of which have too long been taken for granted.

A piece of coal provides roughly eight kilowatt hours of energy per kilogram, which in one sense is extremely efficient. But the coal takes hundreds of millions of years to form. This almost unimaginable quantity of time is consumed with the flick of a switch, or at the press of a button—all dissipated, all devoured in an instant, to light a room or power a computer. When time is factored in, therefore, fossil fuels actually provide surprisingly low efficiency, low yield in terms of a time-energy ratio. A gravity battery, while seemingly of negligible energy storage value compared to fossil fuels, becomes much more powerful when time is factored into the equation.

The ideas underpinning our current exhibition (as the Reconstrained Design Group, until 15 April) at the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (CCCB) represent a radically different philosophy of energy storage and consumption. They indicate a shift away from quick, thoughtless consumption of ancient resources, towards visible, tangible, real-time consumption. Of course, at this stage the Newton Machine is more of an intervention than a practical solution—it is not designed to be an instant fix for the world's energy problems, which are complex and multifaceted.

But before our prototypes and the thinking behind them are dismissed on grounds of impracticality, it is worth noting that our everyday relationship with energy is also a dream, an illusion of through-the-wall magic. It is unsustainable, based on a fantasy of unlimited supply, when in fact it has long been operating on a system of sleight of hand and perpetual deferral. When oil supplies are dwindling, the short-term answer is new technologies of extraction or batteries made from lithium and other non-renewable materials. What the Newton Machine offers is a new way of thinking about energy—a gesture, however rough, towards the seismic paradigm shift that is urgently needed to bring about a more responsible future.

Time is at the centre of this proposed shift in thinking. So is our relationship with nature, which must become balanced rather than extractive and exploitative. Even the generic and ubiquitous electrical sockets in our homes are anything but harmless. The apparent banality of the plug and socket has masked a century of unprecedented environmental destruction. By hiding energy, we have made it seem free of both limitations and consequences. A temporal convenience such as a hot bath or a flash of light releases potential (stored) energy irreversibly. Buttons, switches and plugs conceal enormous infrastructures and exploitation of existing resources on a truly sublime scale.

Design influences desire. If in the past design has been used to encourage consumption, to make consumer goods desirable, then in the future we must enlist design in the fight to bring our desires more closely in line with our needs. A shift is required to preserve what has taken millions or billions of years to form in the past, and to avoid a legacy of waste stretching forward into the future. We have to adjust the scope of our consumption. Reconstraining time means shifting away from the behaviours that brought us into the nightmare of the Anthropocene, and living sustainably within our own modest scale as an animal species on Earth.

Images:

James Auger (top): Gathering black sand for casting at Praia Formosa, Madeira; Miguel Taverna: Images from CCCB exhibition

6 notes

·

View notes