#referenced from a random image i found on pinterest

Text

everyone BE QUIET she is reading a STORY to AURORA

#referenced from a random image i found on pinterest#ive been Attempting more realistic art and it was nice drawing something in this style that wasnt for an assignment#so if she looks a lil funny no she doesnt ♥#kinda wanna draw some spg folks like this i feel like attempting their makeup would be Fun#my art#the mechanisms#nastya rasputina

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

years of pacing

#my art#doodles#oc stuff#man idk what to even call this#I’m in my ‘i found the duplicate layer and color burn options’ phase#anyways. it’s 4 am#i referenced the faces at the front from random pinterest images btw

0 notes

Text

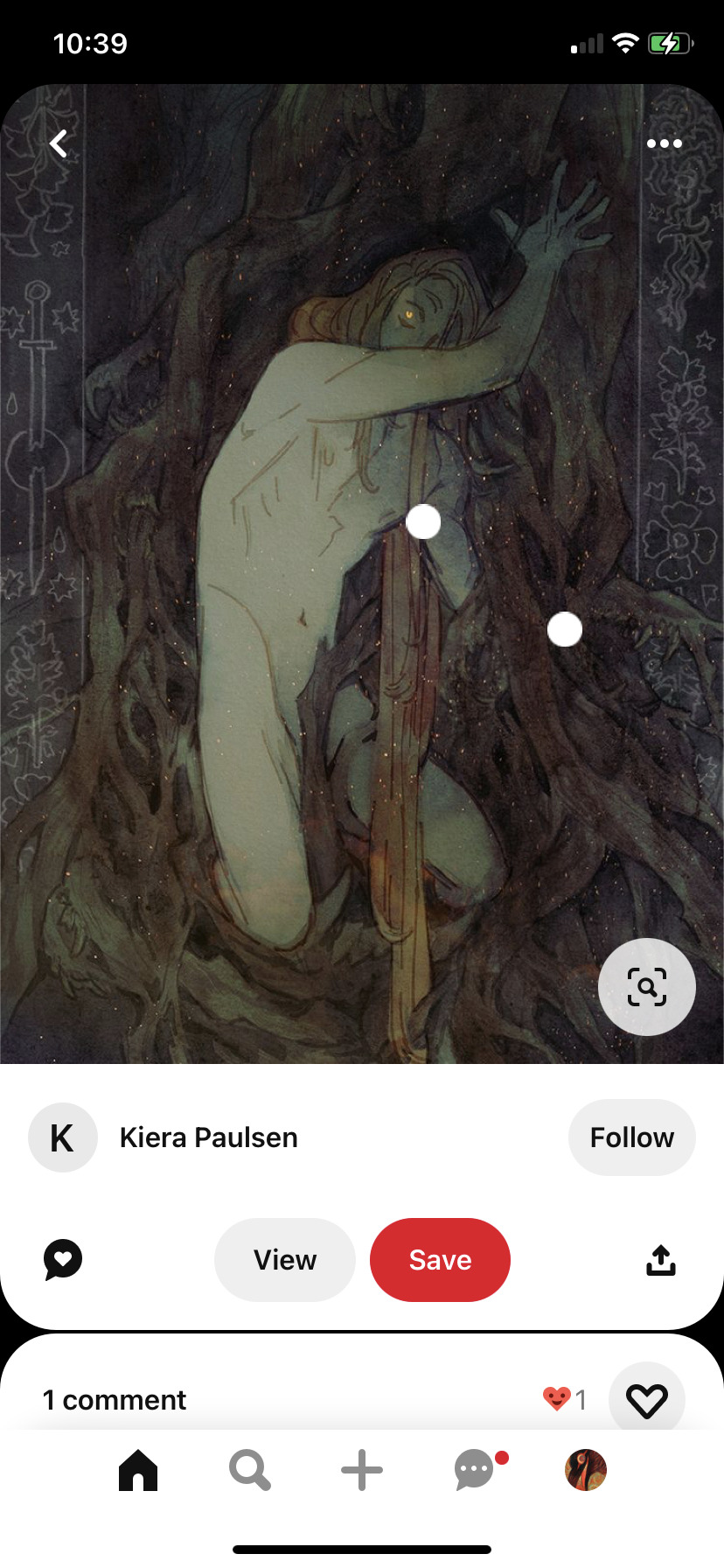

Good Morning, One-Esk

Fanart of the moment Justice of Toren One Esk was woken up from cold storage.

REFERENCE IMAGES:

1) I came across this pose on Pinterest and screenshotted it right away, cuz like it’s such a kickass expressive I had to try drawing it. Sadly I know next to nothing about the original artist. Maybe a person named Kiera Paulsen? Idk I can’t find the original post and only have screenshot rn 😭.

—- edit: a kind soul in the comments found the artist!! Thank you! Artist is @saltweave on twitter https://twitter.com/saltweave/status/135964282496724976

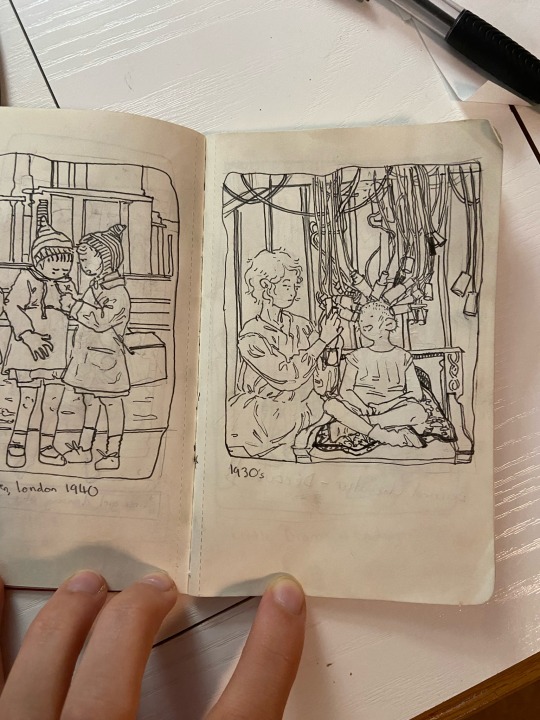

2) a quick doodle I did years ago of a random weird photo I found that had a satisfying half-told-story feeling to it. No idea title of the photo I referenced for the doodle tho.

Even though I imagine the ancillary hookup process would be a lot more organized/less tangled wire-y than what I drew, the chaotic bony mass of wires and hookups is just such a fun look to draw, and I really wanted to put it on the frightened pose so… voila fan-art with artistic liberties taken.

#one esk#justice of toren#ancillary justice#Breq#ann leckie#scifiart#fanart#imperial radch#fleet captain breq

355 notes

·

View notes

Text

fan language: the victorian imaginary and cnovel fandom

there’s this pinterest image i’ve seen circulating a lot in the past year i’ve been on fandom social media. it’s a drawn infographic of a, i guess, asian-looking woman holding a fan in different places relative to her face to show what the graphic helpfully calls “the language of the fan.”

people like sharing it. they like thinking about what nefarious ancient chinese hanky code shenanigans their favorite fan-toting character might get up to—accidentally or on purpose. and what’s the problem with that?

the problem is that fan language isn’t chinese. it’s victorian. and even then, it’s not really quite victorian at all.

--------------------

fans served a primarily utilitarian purpose throughout chinese history. of course, most of the surviving fans we see—and the types of fans we tend to care about—are closer to art pieces. but realistically speaking, the majority of fans were made of cheaper material for more mundane purposes. in china, just like all around the world, people fanned themselves. it got hot!

so here’s a big tipoff. it would be very difficult to use a fan if you had an elaborate language centered around fanning yourself.

you might argue that fine, everyday working people didn’t have a fan language. but wealthy people might have had one. the problem we encounter here is that fans weren’t really gendered. (caveat here that certain types of fans were more popular with women. however, those tended to be the round silk fans, ones that bear no resemblance to the folding fans in the graphic). no disrespect to the gnc old man fuckers in the crowd, but this language isn’t quite masc enough for a tool that someone’s dad might regularly use.

folding fans, we know, reached europe in the 17th century and gained immense popularity in the 18th. it was there that fans began to take on a gendered quality. ariel beaujot describes in their 2012 victorian fashion accessories how middle class women, in the midst of a top shortage, found themselves clutching fans in hopes of securing a husband.

she quotes an article from the illustrated london news, suggesting “women ‘not only’ used fans to ‘move the air and cool themselves but also to express their sentiments.’” general wisdom was that the movement of the fan was sufficiently expressive that it augmented a woman’s displays of emotion. and of course, the more english audiences became aware that it might do so, the more they might use their fans purposefully in that way.

notice, however, that this is no more codified than body language in general is. it turns out that “the language of the fan” was actually created by fan manufacturers at the turn of the 20th century—hundreds of years after their arrival in europe—to sell more fans. i’m not even kidding right now. the story goes that it was louis duvelleroy of the maison duvelleroy who decided to include pamphlets on the language with each fan sold.

interestingly enough, beaujot suggests that it didn’t really matter what each particular fan sign meant. gentlemen could tell when they were being flirted with. as it happens, meaningful eye contact and a light flutter near the face may be a lingua franca.

so it seems then, the language of the fan is merely part of this victorian imaginary we collectively have today, which in turn itself was itself captivated by china.

--------------------

victorian references come up perhaps unexpectedly often in cnovel fandom, most often with regards to modesty.

it’s a bit of an awkward reference considering that chinese traditional fashion—and the ambiguous time periods in which these novels are set—far predate victorian england. it is even more awkward considering that victoria and her covered ankles did um. imperialize china.

but nonetheless, it is common. and to make a point about how ubiquitous it is, here is a link to the twitter search for “sqq victorian.” sqq is the fandom abbreviation for shen qingqiu, the main character of the scum villain’s self-saving system, by the way.

this is an awful lot of results for a search involving a chinese man who spends the entire novel in either real modern-day china or fantasy ancient china. that’s all i’m going to say on the matter, without referencing any specific tweet.

i think people are aware of the anachronism. and i think they don’t mind. even the most cursory research reveals that fan language is european and a revisionist fantasy. wikipedia can tell us this—i checked!

but it doesn’t matter to me whether people are trying to make an internally consistent canon compliant claim, or whether they’re just free associating between fan facts they know. it is, instead, more interesting to me that people consistently refer to this particular bit of history. and that’s what i want to talk about today—the relationship of fandom today to this two hundred odd year span of time in england (roughly stuart to victorian times) and england in that time period to its contemporaneous china.

things will slip a little here. victorian has expanded in timeframe, if only because random guys posting online do not care overly much for respect for the intricacies of british history. china has expanded in geographic location, if only because the english of the time themselves conflated china with all of asia.

in addition, note that i am critiquing a certain perspective on the topic. this is why i write about fan as white here—not because all fans are white—but because the tendencies i’m examining have a clear historical antecedent in whiteness that shapes how white fans encounter these novels.

i’m sure some fans of color participate in these practices. however i don’t really care about that. they are not its main perpetrators nor its main beneficiaries. so personally i am minding my own business on that front.

it’s instead important to me to illuminate the linkage between white as subject and chinese as object in history and in the present that i do argue that fannish products today are built upon.

--------------------

it’s not radical, or even new at all, for white audiences to consume—or create their own versions of—chinese art en masse. in many ways the white creators who appear to owe their whole style and aesthetic to their asian peers in turn are just the new chinoiserie.

this is not to say that white people can’t create asian-inspired art. but rather, i am asking you to sit with the discomfort that you may not like the artistic company you keep in the broader view of history, and to consider together what is to be done about that.

now, when i say the new chinoiserie, i first want to establish what the original one is. chinoiserie was a european artistic movement that appeared coincident with the rise in popularity of folding fans that i described above. this is not by coincidence; the european demand for asian imports and the eventual production of lookalikes is the movement itself. so: when we talk about fans, when we talk about china (porcelain), when we talk about tea in england—we are talking about the legacy of chinoiserie.

there are a couple things i want to note here. while english people as a whole had a very tenuous knowledge of what china might be, their appetites for chinoiserie were roughly coincident with national relations with china. as the relationship between england and china moved from trade to out-and-out wars, chinoiserie declined in popularity until china had been safely subjugated once more by the end of the 19th century.

the second thing i want to note on the subject that contrary to what one might think at first, the appeal of chinoiserie was not that it was foreign. eugenia zuroski’s 2013 taste for china examines 18th century english literature and its descriptions of the according material culture with the lens that chinese imports might be formative to english identity, rather than antithetical to it.

beyond that bare thesis, i think it’s also worthwhile to extend her insight that material objects become animated by the literary viewpoints on them. this is true, both in a limited general sense as well as in the sense that english thinkers of the time self-consciously articulated this viewpoint. consider the quote from the illustrated london news above—your fan, that object, says something about you. and not only that, but the objects you surround yourself with ought to.

it’s a bit circular, the idea that written material says that you should allow written material to shape your understanding of physical objects. but it’s both 1) what happened, and 2) integral, i think, to integrating a fannish perspective into the topic.

--------------------

japanning is the name for the popular imitative lacquering that english craftspeople developed in domestic response to the demand for lacquerware imports. in the eighteenth century, japanning became an artform especially suited for young women. manuals were published on the subject, urging young women to learn how to paint furniture and other surfaces, encouraging them to rework the designs provided in the text.

it was considered a beneficial activity for them; zuroski describes how it was “associated with commerce and connoisseurship, practical skill and aesthetic judgment.” a skillful japanner, rather than simply obscuring what lay underneath the lacquer, displayed their superior judgment in how they chose to arrange these new canonical figures and effects in a tasteful way to bring out the best qualities of them.

zuroski quotes the first english-language manual on the subject, written in 1688, which explains how japanning allows one to:

alter and correct, take out a piece from one, add a fragment to the next, and make an entire garment compleat in all its parts, though tis wrought out of never so many disagreeing patterns.

this language evokes a very different, very modern practice. it is this english reworking of an asian artform that i think the parallels are most obvious.

white people, through their artistic investment in chinese material objects and aesthetics, integrated them into their own subjectivity. these practices came to say something about the people who participated in them, in a way that had little to do with the country itself. their relationship changed from being a “consumer” of chinese objects to becoming the proprietor of these new aesthetic signifiers.

--------------------

i want to talk about this through a few pairs of tensions on the subject that i think characterize common attitudes then and now.

first, consider the relationship between the self and the other: the chinese object as something that is very familiar to you, speaking to something about your own self vs. the chinese object as something that is fundamentally different from you and unknowable to you.

consider: [insert character name] is just like me. he would no doubt like the same things i like, consume the same cultural products. we are the same in some meaningful way vs. the fast standard fic disclaimer that “i tried my best when writing this fic, but i’m a english-speaking westerner, and i’m just writing this for fun so...... [excuses and alterations the person has chosen to make in this light],” going hand-in-hand with a preoccupation with authenticity or even overreliance on the unpaid labor of chinese friends and acquaintances.

consider: hugh honour when he quotes a man from the 1640s claiming “chinoiserie of this even more hybrid kind had become so far removed from genuine Chinese tradition that it was exported from India to China as a novelty to the Chinese themselves”

these tensions coexist, and look how they have been resolved.

second, consider what we vest in objects themselves: beaujot explains how the fan became a sexualized, coquettish object in the hands of a british woman, but was used to great effect in gilbert and sullivan’s 1885 mikado to demonstrate the docility of asian women.

consider: these characters became expressions of your sexual desires and fetishes, even as their 5’10 actors themselves are emasculated.

what is liberating for one necessitates the subjugation and fetishization of the other.

third, consider reactions to the practice: enjoyment of chinese objects as a sign of your cosmopolitan palate vs “so what’s the hype about those ancient chinese gays” pop culture explainers that addressed the unconvinced mainstream.

consider: zuroski describes how both english consumers purchased china in droves, and contemporary publications reported on them. how:

It was in the pages of these papers that the growing popularity of Chinese things in the early eighteenth century acquired the reputation of a “craze”; they portrayed china fanatics as flawed, fragile, and unreliable characters, and frequently cast chinoiserie itself in the same light.

referenda on fannish behavior serve as referenda on the objects of their devotion, and vice versa. as the difference between identity and fetish collapses, they come to be treated as one and the same by not just participants but their observers.

at what point does mxtx fic cease to be chinese?

--------------------

finally, it seems readily apparent that attitudes towards chinese objects may in fact have something to do with attitudes about china as a country. i do not want to suggest that these literary concerns are primarily motivated and begot by forces entirely divorced from the real mechanics of power.

here, i want to bring in edward said, and his 1993 culture and imperialism. there, he explains how power and legitimacy go hand in hand. one is direct, and one is purely cultural. he originally wrote this in response to the outsize impact that british novelists have had in the maintenance of empire and throughout decolonization. literature, he argues, gives rise to powerful narratives that constrain our ability to think outside of them.

there’s a little bit of an inversion at play here. these are chinese novels, actually. but they’re being transformed by white narratives and artists. and just as i think the form of the novel is important to said’s critique, i think there’s something to be said about the form that fic takes and how it legitimates itself.

bound up in fandom is the idea that you have a right to create and transform as you please. it is a nice idea, but it is one that is directed towards a certain kind of asymmetry. that is, one where the author has all the power. this is the narrative we hear a lot in the history of fandom—litigious authors and plucky fans, fanspaces always under attack from corporate sanitization.

meanwhile, said builds upon raymond schwab’s narrative of cultural exchange between european writers and cultural products outside the imperial core. said explains that fundamental to these two great borrowings (from greek classics and, in the so-called “oriental renaissance” of the late 18th, early 19th centuries from “india, china, japan, persia, and islam”) is asymmetry.

he had argued prior, in orientalism, that any “cultural exchange” between “partners conscious of inequality” always results in the suffering of the people. and here, he describes how “texts by dead people were read, appreciated, and appropriated” without the presence of any actual living people in that tradition.

i will not understate that there is a certain economic dynamic complicating this particular fannish asymmetry. mxtx has profited materially from the success of her works, most fans will not. also secondly, mxtx is um. not dead. LMAO.

but first, the international dynamic of extraction that said described is still present. i do not want to get overly into white attitudes towards china in this post, because i am already thoroughly derailed, but i do believe that they structure how white cnovel fandom encounters this texts.

at any rate, any profit she receives is overwhelmingly due to her domestic popularity, not her international popularity. (i say this because many of her international fans have never given her a cent. in fact, most of them have no real way to.) and moreover, as we talk about the structure of english-language fandom, what does it mean to create chinese cultural products without chinese people?

as white people take ownership over their versions of stories, do we lose something? what narratives about engagement with cnovels might exist outside of the form of classic fandom?

i think a lot of people get the relationship between ideas (the superstructure) and production (the base) confused. oftentimes they will lob in response to criticism, that look! this fic, this fandom, these people are so niche, and so underrepresented in mainstream culture, that their effects are marginal. i am not arguing that anyone’s cql fic causes imperialism. (unless you’re really annoying. then it’s anyone’s game)

i’m instead arguing something a little bit different. i think, given similar inputs, you tend to get similar outputs. i think we live in the world that imperialism built, and we have clear historical predecessors in terms of white appetites for creating, consuming, and transforming chinese objects.

we have already seen, in the case of the fan language meme that began this post, that sometimes we even prefer this white chinoiserie. after all, isn’t it beautiful, too?

i want to bring discomfort to this topic. i want to reject the paradigm of white subject and chinese object; in fact, here in this essay, i have tried to reverse it.

if you are taken aback by the comparisons i make here, how can you make meaningful changes to your fannish practice to address it?

--------------------

some concluding thoughts on the matter, because i don’t like being misunderstood!

i am not claiming white fans cannot create fanworks of cnovels or be inspired by asian art or artists. this essay is meant to elaborate on the historical connection between victorian england and cnovel characters and fandom that others have already popularized.

i don’t think people who make victorian jokes are inherently bad or racist. i am encouraging people to think about why we might make them and/or share them

the connections here are meant to be more provocative than strictly literal. (e.g. i don’t literally think writing fanfic is a 1-1 descendant of japanning). these connections are instead meant to 1) make visible the baggage that fans of color often approach fandom with and 2) recontextualize and defamiliarize fannish practice for the purposes of honest critique

please don’t turn this post into being about other different kinds of discourse, or into something that only one “kind” of fan does. please take my words at face value and consider them in good faith. i would really appreciate that.

please feel free to ask me to clarify any statements or supply more in-depth sources :)

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Impact of Dystopian Novels on Gen Z

In the following post, I will be discussing the digital revolution as well as YA novels, namely the dystopian type from the late 2000’s to the early 2010’s, and the various impacts they have had on Generation Z. I will focus mainly on the effects of fandom culture as well as the adoption of culture and characteristics of fictional realities, and the emergence of the dystopian female lead trope.

Following the digital revolution, access to information and discussion platforms (such as Tumblr) became rampant. Fandoms hence became one of the dominant modes of engagement online. People across the globe could now find a community of people who share the same interests on the same platform, hence creating common ground for like-minded people to relate. That being said, fan culture existed way before the arrival of the internet, but I will be specifically referencing the post-internet understanding of fandoms as that is what I can relate to. The arrival of the internet led to a new level of globalization of fandom culture. (Janya Sindhu, 2019) These communities were based off popular culture such as tv shows, books, films, music, and more. I will be discussing the impacts of The Huger Games series and the Divergent series.

Both novels are set in dystopian, futuristic realities where the general population has been divided into separate classes. In the Hunger Games, we are introduced to the concept of “districts”, running from 1-12, where each district is in charge of a specific industry. This is a fascinating depiction of classism as it clearly demonstrates the disparity between amount of work and the level of compensation received depending on which district you were born in. Katniss Everdeen, the protagonist, was born into the 12th, the poorest district, which focuses on coal. (Henthorne, T., 2012)

On the other hand, the Divergent series is separated into factions. There are five factions, Erudite (the intelligent), Amity (the peaceful), Candor (the honest), Abnegation (the selfless) and Dauntless (the brave). In the divergent universe, people are born into a faction, and on their sixteenth birthday, they can choose which faction they wish to switch to. From then on, they have to forget who they once were (including their families) and adopt the traits of their new persona.

The reason I am explaining these fictional social systems is that following the arrival of social media platforms, people began relating and adopting certain aspects of these novels. People could now order the signature mocking jay pin worn by Katniss Everdeen as a symbol of revolution, or perhaps her bow and arrow, As for Divergent, online quizzes could tell you what your true faction was depending on your personality. What was once a figment of one’s imagination, generated by a script could now feel and seem as real as ever. You could now literally immerse yourself in these universes with some kind of physical “proof”. (Janya Sindhu, 2019)

One of the first instances of this happening was following the Harry Potter boom, where the different Houses and their given specific personality traits created an obsession amongst fans to see where they fit in. People began adopting these traits and labeling themselves accordingly. Obsession could hence be legitimized and encouraged. The development of a new kind of fan known as a stan where someone revolves their entire like and personality around a specific cultural idol can be observed here. The internet, where personality quizzes, discussion platforms, immediate and intimate access to celebrities through Instagram and more injected fandom and stan culture with an extra strength dose of false legitimacy. Even if the algorithm that creates these life altering claims off of 12 seemingly random questions is completely random, the obsession some people have with inserting themselves in their beloved fictional universe will legitimize nearly anything.

Moreover, Gen Z has grown up reading these dystopian novels and idolizing their female protagonists. Katniss and Tris (the protagonist from the Divergent series) heavily impacted me growing up. It was once of the first instances that I can remember where the lead female was not depicted as the damsel in distress, but as the hero. On multiple occasions, both Katniss and Tris were both the brains and the muscle behind successful operations aiming to either overthrow their corrupt governments or save their male love interests. (Balkind, 2014) Unfortunately, both of these novels only depicted hetero-normative relationships. That being said young girls everywhere began idolizing these characters as it finally gave us a positive depiction of woman in sci fi where their looks and sexuality were not the main focus. Women began wearing their hair in a single French braid pushed to the side because “that’s how Katniss wears hers”. I was absolutely one of those girls. There is a certain empowerment that comes with mimicking one’s heroine, especially at such a young age. In the Divergent series, Tris joins the Dauntless faction where she breaks down gender stereotypes by becoming one of the most lethal members of the faction. (Wiyani, et al., 2017) Katniss is a really interesting character as she demonstrates typically male characteristics (such as being removed, thinking with her head and confidence) all the while maintaining her compassionate side which is shown to her loved ones. The female dystopian lead trope is one of my favourites as, more often than not, these women clearly struggle with trying to find balance with where and how they fit in with society as so many women do. They are absolutely not perfect and often make biased choices and mistakes but that is what I believe makes them so relatable. (Nelson, C., 2014)

To conclude, in my opinion, Generation Z is becoming one of the most outspoken and influential generations yet. With access to information at the tip of our fingers and platforms such as TikTok, twitter, Instagram, etc., our voices and opinions can be shared effortlessly. Growing up with rebellious and headstrong icons such as Tris and Katniss have given young women a chance to see how powerful one person’s voice can be when utilized properly. In the context of fandom and stan culture, the impact of the digital revolution is incomparable.

References:

2015. What Divergent faction are you?. [image] Available at:

<https://www.playbuzz.com/ralflet210/what-divergent-faction-are-you> [Accessed 2 May 2021].

Henthorne, T., 2012. Approaching The Hunger Games trilogy: A literary and cultural

analysis. McFarland.

https://br.pinterest.com/saradomonkoov/ - Image taken from Pinterest

Wiyani, N.P., Sili, S. and Valiantien, N.M., 2017. The Psychoanalytical Study on The

Characteristics and Causes of Adolescent Deviant Behavior Found in Divergent Novel by Veronica Roth. Ilmu Budaya: Jurnal Bahasa, Sastra, Seni dan Budaya, 1(2).

Janya Sindhu, 2019, Medium Journal, How the Internet has made Fandom Culture

Powerful. [online] Available

at: <https://medium.com/swlh/how-the-internet-has-made-fandom-culture-powerful-7609ae60e4bf> [Accessed 2 May 2021].

Reid, S. and Stringer, S., 1997. Ethical dilemmas in teaching problem novels: The

psychological impact of troubling YA literature on adolescent readers in the classroom.

Balkind, N 2014, Fan Phenomena : The Hunger Games, Intellect Books Ltd, Bristol.

Available from: ProQuest Ebook Central. [1 May 2021].

Nelson, C., 2014. Female rebellion in young adult dystopian fiction. Ashgate Publishing,

Ltd..

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Even more AI Practice

I’m not saying I’m an artist because I drew a wicked cool heart on Lana Del Rey, but I will say that I’m proud of my latest endeavor with Adobe Illustrator. Going into this, I knew I wanted to create some kind of drawing, but I also knew I wouldn’t be good enough to just draw from scratch on a blank canvas… especially when I’m doing it on a macbook. I decided to draw on an image of Lana because she never fails to inspire me, so I knew I would be more likely to get this done. I began by looking up “Lana Del Rey Drawing” on Pinterest and searching for inspiration. After scrolling for a while, I finally found a drawing that sparked my creativity ( https://pin.it/53UTsqn ). I knew the exact image that the artist had referenced in their drawing, so I found it pretty quickly after a few google searches (The image is owned by Complex Networks. I don’t claim any ownership of the image.) I uploaded it to canvas and started by drawing the bright red background of the heart, followed by outlining it in a darker red and then drawing random lines for veins. I also decided to add a blue even though the artist hadn’t used blue in theirs. I thought it gave it more color. I know the heart doesn’t look the best, but it was the most I could do on a computer and I definitely feel a sense of accomplishment after getting this done! I just love how it looks. Overall, this took me a little less than an hour, but I know that next time will be quicker and easier because I am now more familiar with the paintbrush tool!

0 notes