#the idea that oppenheimer would have been better or more respectful if there had been some random cut to people in japan or the new mexico

Text

Movies that attempt something different, that recognize that less can indeed be more, are thus easily taken to task. “It’s so subjective!” and “It omits a crucial P.O.V.!” are assumed to be substantive criticisms rather than essentially value-neutral statements. We are sometimes told, in matters of art and storytelling, that depiction is not endorsement; we are not reminded nearly as often that omission is not erasure. But because viewers of course cannot be trusted to know any history or muster any empathy on their own — and if anything unites those who criticize “Oppenheimer” on representational grounds, it’s their reflexive assumption of the audience’s stupidity — anything that isn’t explicitly shown onscreen is denigrated as a dodge or an oversight, rather than a carefully considered decision.

A film like “Oppenheimer” offers a welcome challenge to these assumptions. Like nearly all Nolan’s movies, from “Memento” to “Dunkirk,” it’s a crafty exercise in radical subjectivity and narrative misdirection, in which the most significant subjects — lost memories, lost time, lost loves — often are invisible and all the more powerful for it. We can certainly imagine a version of “Oppenheimer” that tossed in a few startling but desultory minutes of Japanese destruction footage. Such a version might have flirted with kitsch, but it might well have satisfied the representational completists in the audience. It also would have reduced Hiroshima and Nagasaki to a piddling afterthought; Nolan treats them instead as a profound absence, an indictment by silence.

That’s true even in one of the movie’s most powerful and contested sequences. Not long after news of Hiroshima’s destruction arrives, Oppenheimer gives a would-be-triumphant speech to a euphoric Los Alamos crowd, only for his words to turn to dust in his mouth. For a moment, Nolan abandons realism altogether — but not, crucially, Oppenheimer’s perspective — to embrace a hallucinatory horror-movie expressionism. A piercing scream erupts in the crowd; a woman’s face crumples and flutters, like a paper mask about to disintegrate. The crowd is there and then suddenly, with much sonic rumbling, image blurring and an obliterating flash of white light, it is not.

For “Oppenheimer’s” detractors, this sequence constitutes its most grievous act of erasure: Even in the movie’s one evocation of nuclear disaster, the true victims have been obscured and whitewashed. The absence of Japanese faces and bodies in these visions is indeed striking. It’s also consistent with Nolan’s strict representational parameters, and it produces a tension, even a contradiction, that the movie wants us to recognize and wrestle with. Is Oppenheimer trying (and failing) to imagine the hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians murdered by the weapon he devised? Or is he envisioning some hypothetical doomsday scenario still to come?

I think the answer is a blur of both, and also something more: In this moment, one of the movie’s most abstract, Nolan advances a longer view of his protagonist’s history and his future. Oppenheimer’s blindness to Japanese victims and survivors foreshadows his own stubborn inability to confront the consequences of his actions in years to come. He will speak out against nuclear weaponry, but he will never apologize for the atomic bombings of Japan — not even when he visits Tokyo and Osaka in 1960 and is questioned by a reporter about his perspective now. “I do not think coming to Japan changed my sense of anguish about my part in this whole piece of history,” he will respond. “Nor has it fully made me regret my responsibility for the technical success of the enterprise.”

Talk about compartmentalization. That episode, by the way, doesn’t find its way into “Oppenheimer,” which knows better than to offer itself up as the last word on anything. To the end, Nolan trusts us to seek out and think about history for ourselves. If we elect not to, that’s on us.

#what I'm reading#oppenheimer#nuclear power#inject this entire essay into my veins#part of what makes oppenheimer such a powerful movie is how closely it hews to its subject matter#except for the hearing plotline we see what he sees. we feel what he feels#the people who were building the bombs never saw its effects. they lived in a tiny town deliberately cut off from the rest of the world#and when their labors bore fruit they heard about it on the radio like everyone else in the country#oppenheimer included. inventing something doesn't give you special power into what it actually looks like when it's used. that's the danger#the idea that oppenheimer would have been better or more respectful if there had been some random cut to people in japan or the new mexico#desert being bombed frankly strikes me as incredibly gauche#and the idea that this movie needs to encompass every aspect of the bombings because it would be unrealistic or unfair to expect people#to seek out any additional knowledge that can't be found in a blockbuster movie is just so insulting to our collective intelligence

68 notes

·

View notes

Note

and none for bradley cooper! you love to see it

He was MAD too. You could see it written on his face, and he's always been rumored to have thrown a fit over not getting nominated for Best Director for ASIB (even though he WAS nominated for Best Actor).

I think he's just... so bizarrely entitled. I'm not saying he isn't a talented actor (directing... who knows if ASIB was a fluke, and I do think he benefited from it being a remake, with three versions to draw from--it wasn't even the first one to focus on the music industry versus the movie industry). But Bradley was a comedy guy for years, and many of those movies were absolute stinkers. The Hangover Part II and III, He's Just Not That Into You, ALL ABOUT STEVE??? He was the "Not Michael Vartan" on Alias.

He really began to turn it around (moviewise) with Silver Linings Playbook and his other David O. Russell movies (which....) and tbh other actors understandably always got more attention--Jennifer Lawrence, Christian Bale, Amy Adams. He wasn't ever this guy who LOST BY A HAIR or was seen as like... super respected but passed over. Leonardo DiCaprio, easily one of the best actors of his gen, got passed over for an Oscar 4x (never mind the times when he wasn't nominated and should've been lol) and he's probably about to have another loss lol. Bradley has been nommed 4x, and let me tell you, he ain't Leo.

It seems like he has this very "I'm due" perspective, when much better actors, including those who have BEEN respected and seen as True Artists for way longer than he has (like Cillian) have waited way longer to get their flowers. It's like... no dude. You have been THISCLOSE to clinching.

Like, let's get granular. SLP, he lost to DANIEL DAY-LEWIS. DDL. One of the GOATs. Did you REALLY think you were gonna beat DANIEL. DAY-LEWIS. There were (other) better performances than Bradley that year (I think Denzel was excellent in Flight) but it wasn't even close, dude.

American Hustle--admittedly this was a shitty category that year, full of shitty people. But Jared Leto was very much seen as a shoe-in, as much as I hate to say it. Barkhad Abdi, I'm sorry.

American Sniper--honestly, such a bad movie lol. And he lost to Eddie Redmayne (whew, The Theory of Everything has taken a hit recently) who was in a very standard, "he had to work really hard physically" movie, but like... he did legit have to do some challenging work. And if it wasn't him, it would've been Michael Keaton, who was in a really different movie and had a strong comeback narrative.

ASIB--honestly, his strongest showing to me, but he wasn't ever gonna win. Rami was seen as obligatory after Bohemian Rhapsody. Which... I think Rami is a great actor. BR was a mess with a frankly disrespectful depiction of Freddie Mercury. I don't think it was THAT GREAT a performance either. But he did go into it very expected to win. This is probably the closest Bradley got and honestly, I would've given it to him because the category was weak that year, but I don't think he had a REALLY GOOD chance. Rami was anointed by then. And tbh, when he got passed over for Best Director... I think the writing was on the wall. I think he over-campaigned, and Lady Gaga was the real centerpiece and everyone knew it.

Again, this really wasn't a moment where it's like "WHEN WILL HE HAVE HIS MOMENT" like Leo. He's a good actor. There are a LOTTA better actors. The idea that he can compete with Cillian in... any of the above performances, let alone in MAESTRO, against what Cillian did in Oppenheimer especially, is delusional lol. Tommy Shelby Cillian, if he was up for an Oscar, would step on Bradley performance-wise, let alone Oppenheimer. I'm not even an Oppenheimer stan, but the black and white shots of him with the hat alone are like, already kinda icon lol. This. Is. His. Moment.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

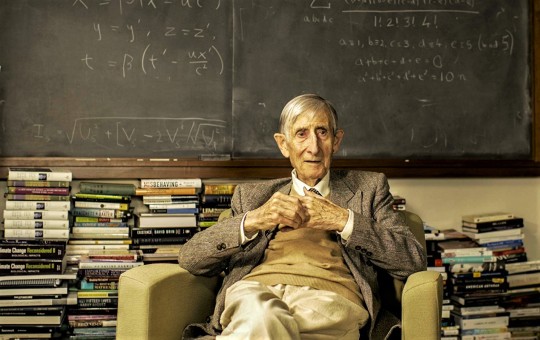

The physicist Freeman Dyson, who has died aged 96, became famous within science for mathematical solutions so advanced that they could only be applied to complex problems of atomic theory and popular with the public for ideas so far-fetched they seemed beyond lunacy.

As a young postgraduate student, Dyson devised – while taking a Greyhound bus ride in America – the answer to a conundrum in quantum electrodynamics that had stumped giants of physics such as Richard Feynman and Hans Bethe. As an author, guru and apostle for science, Dyson also cheerfully proposed that humans might genetically engineer trees that could grow on comets, to provide new habitats for genetically altered humans.

He had already proposed the ultimate solution to the energy crisis: a sufficiently advanced civilisation would, he argued, crunch up all the unused planets and asteroids to form a giant shell around its parent star, to reflect and exploit its radiation. Science fiction writers were delighted. The first suggestion became known as the Dyson tree. The second is called the Dyson sphere.

He was born in Crowthorne, Berkshire. His father, George Dyson, was a musician and composer, and his mother, Mildred Atkey, a lawyer. The young Dyson reported that his happiest ever school holiday – from Winchester college – was spent working his way, from 6am to 10pm, through 700 problems in Piaggio’s Differential Equations. “I intended to speak the language of Einstein,” he said in his 1979 memoir Disturbing the Universe. “I was in love with mathematics and nothing else mattered.”

He graduated from Cambridge and in 1943 became a civilian scientist with RAF Bomber Command, which experienced hideous losses with each raid over Germany. Dyson and his colleagues suggested that the Lancaster bomber’s gun turrets slowed the plane, increased its burden and made it more vulnerable to German fighters: without the turrets, it might gain an extra 50mph and be much more manoeuvrable.

He was ignored. Bomber Command, he was later to write, “might have been invented by a mad scientist as an example to exhibit as clearly as possible the evil aspects of science and technology: the Lancaster, in itself a magnificent flying machine, made into a death trap for the boys who flew it. A huge organisation dedicated to the purpose of burning cities and killing people, and doing it badly.”

The young Dyson was already convinced of some moral purpose to the universe and remained a non-denominational Christian all his life.

After the second world war he went to Cornell University in New York state to begin research in physics under Bethe, one of the team at Los Alamos that fashioned the atomic bomb.

By 1947, the challenge was one of pure science: to forge an accurate theory that described how atoms and electrons behaved when they absorbed or emitted light. The broad basis of what was called quantum electrodynamics had been proposed by the British scientist Paul Dirac and other giants of physics. The next step was to calculate the precise behaviour inside an atom. Using different approaches, both Julian Schwinger and Feynman delivered convincing solutions, but their answers did not quite square with each other.

It was while crossing Nebraska by bus, reading James Joyce and the biography of Pandit Nehru, that the young Dyson saw how to resolve the work of the two men and help win them the 1965 Nobel prize: “It came bursting into my consciousness, like an explosion,” Dyson wrote. “I had no pencil and paper, but everything was so clear I did not need to write it down.”

A few days later he moved – for almost all of the rest of his life – to the Institute of Advanced Study at Princeton, home of Albert Einstein and Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb. “It was exactly a year since I had left England to learn physics from the Americans. And now here I was a year later, walking down the road to the institute on a fine September morning, to teach the great Oppenheimer how to do physics. The whole situation seemed too absurd to be credible,” Dyson wrote later.

He went on to deliver a series of papers that resolved the problems of quantum electrodynamics. He did not share in Feynman’s and Schwinger’s Nobel prize. He did not complain. “I was not inventing new physics,” he said. “I merely clarified what was already there so that others could see the larger picture.”

Dyson tackled complex problems in theoretical physics and mathematics – there is a mathematical tool called the Dyson series, and another called Dyson’s transform – and enjoyed the affection and respect of scientists everywhere. He took US citizenship, and worked on Project Orion, one of America’s oddest and most ambitious space ventures.

Orion was to be an enormous spacecraft, with a crew of 200 scientists and engineers, driven by nuclear weapons: warheads would be ejected one after another from the spaceship and detonated. This repeated pulse of blasts would generate speeds so colossal that the spacecraft could reach Mars in two weeks, and get to Saturn, explore the planet’s moons, and get back to Earth again within seven months. Modern spacecraft launched by chemical rockets can take 12 months to reach Mars, and more than seven years to reach Saturn.

The Orion project faltered under the burden of technical problems, and then was abandoned in 1965 after the partial test ban treaty that outlawed nuclear explosions in space.

Dyson was a widely read man with a gift for memorable remarks and a great talent for presenting – with calm logic and bright language – ideas for which the term “outside the envelope” could only be the most feeble understatement.

In 1960, in a paper for the journal Science, he argued that a technologically advanced civilisation would sooner or later surround its home star with reflective material to make full use of all its radiation. The extraterrestrials could do this by pulverising a planet the size of Jupiter, and spreading its fabric in a thin shell around their star, at twice the distance of the Earth from the sun. Although the starlight would be masked, the shell or sphere would inevitably warm up. So people seeking extraterrestrial intelligence should first look for a very large infrared glow somewhere in the galaxy.

In 1972 – a year before the first serious experiments in manipulating DNA – Dyson outlined, in a Birkbeck College lecture, in London, his vision of biological engineering. He predicted that scavenging microbes could be altered to harvest minerals, neutralise toxins and to clean up plastic litter and hazardous radioactive materials.

He then proposed that comets – lumps of ice and organic chemicals that periodically orbit the sun – could serve as nurseries for genetically altered trees that could grow, in the absence of gravity, to heights of hundreds of miles, and release oxygen from their roots to sustain human life. “Seen from far away, the comet will look like a small potato sprouting an immense growth of stems and foliage. When man comes to live on the comets, he will find himself returning to the arboreal existence of his ancestors,” he told a delighted audience.

He went on to predict robot explorers that could replicate themselves, and plants that would make seeds and propagate across the galaxy. Plants could grow their own greenhouses, he argued, just as turtles could grow shells and polar bears grow fur. His audience may not have believed a word, but they listened intently.

Dyson had a gift for the memorable line and a disarming honesty that admitted the possibility of error. It was, he would say, better to be wrong than to be vague, and much more fun to be contradicted than to be ignored. Dyson was by instinct and reason a pacifist, but he understood the fascination with nuclear weaponry.

He enjoyed unorthodox propositions and contrarian arguments; he maintained a certain scepticism about climate change (“the fuss about global warming is greatly exaggerated”) and he argued that a commercial free-for-all was more likely to deliver the right design for spacecraft than a government-directed effort.

He had little patience with those physicists who argued that the world was the consequence of blind chance. “The more I examine the universe and the details of its architecture, the more evidence I find that the universe must in some sense have known we were coming,” he once said.

His Cambridge mentor, the mathematician GH Hardy, had told him: “Young men should prove theorems, old men should write books.” After Disturbing the Universe, Dyson wrote a number of compelling books, including Infinite in All Directions (1988) and Imagined Worlds (1997). In 2000, he was awarded the Templeton prize – worth more than the Nobel – given annually for progress towards discoveries about spiritual realities.

He was a frequent essayist and to the end a contributor to the New York Review of Books. But he continued to think as a scientist and in 2012 entered the field of mathematical biology with a published paper on game theory in human cooperation and Darwinian evolution.

Dyson is survived by his second wife, Imme (nee Jung), whom he married in 1958, and their four daughters, Dorothy, Emily, Mia and Rebecca; by a son, George, and daughter, Esther, from his first marriage, to Verena Huber, which ended in divorce; and by a stepdaughter, Katarina, and 16 grandchildren.

• Freeman John Dyson, mathematician and physicist, born 15 December 1923; died 28 February 2020

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

-11.03.2021- Thursday Lecture Surrealism

The beginning of this lecture started with Julie showing a video of the brief history of surrealism which was presented by Peter Capaldi. I already found myself at ease with this formatting of information as I often find it very difficult to have a good basic understanding of a subject through how its presented by master’s degree lecturers. I have always found it difficult to gain a good understanding on the basics and in-depth segments of subjects and art movements such as surrealism or post-modernism (( or any )) as I cant take in the information the way its presented to me. I’ve tried multiple times to purchase and read books on several art movements and pivotal moments in history, but I just can’t take it in and understand it, and I find it makes some of these lectures difficult for me. I know the lectures cant possibly fit around my specific way of learning and taking in information, but part of me wishes they had more videos like this at the start of each lecture on a subject, or a simple overview of what it is. Even if it was just something they decided to email out after each lecture as a way of helping others like me gain a better understanding and foundation of each subject. Overall, I felt I learnt a lot about surrealism just from this small segment from TATE Shots. For example I learned how surrealism started in 1924 in the Les Deux Magots café by poet Andre Breton, which is something I never learned from all the over-complicated books and websites I found on surrealism as they always seemed to be over pinned by words I didn’t understand or pages of text before getting to where it started in the first place – its something very confusing and frustrating for me when this is something that seemingly comes so easy to others. I was happy to learn more throughout this clip such as how Breton published a manifest that was inspired by psychoanalysist Sigmund Freud who then wrote a book called The Interpretation of Dreams. Throughout this book he explored the idea of which he believed there was a deep layer of the human mind where memory and our most basic instincts are stored – he called this the unconscious mind, as most times we were unaware of it. Breton believed that art and literature could represent the unconscious mind. He found artists who also followed this belief such as Salvador Dali, Max Ernst, Meret Oppenheim and Claude Cahun - ((one of my personal favourite surrealist and Dadaist artists!)) Throughout the video it is then explained how a lot of surrealist art was about sex as Freud believed the motivation for all things in life was sex, to which he then later changed his mind. Surrealists enjoy putting objects together that aren’t normally associated with one another; a form of juxtaposition; to make something that was playful and disturbing at the same time in order to stimulate the unconscious mind. Something interesting I found when looking at the visuals shown throughout this explanation in the video was how I felt oddly connected to the idea of the fox head and the metronome and its additionally something id like to explore through a sketch of my own as a direct inspiration from this lecture and the movement of surrealism.

*show my sketch//idea – blood, metronome ticking and cutting throat, blood pooling*

Throughout this video it was also explained how there are two kinds of surrealist painting: one about dreams featuring lots of Freudian symbols such as apples, hats and birds. The other called Automatism, inspired by Freud’s idea of free association which was deigned to reveal the unconscious mind. An example of Automatism is a piece by Joan Miro with his piece Painting’ made in 1927. This piece is mainly blue as Miro liked to interpret dreams using the colour blue, the shapes are arbitrary and random as if drawn from the artist’s unconscious mind. Miro’s conscious mind has then turned the shapes into objects such as a shooting star, a breast or a horse.

There were also surrealist films such as the most famous called Un Chein Andalou in 1929 by artists Luis Bunuel and Salvador Dali. This film was best known for its scene in which Bunuel’s eye is cut open. I understand how some people are very put-off by this scene, which is understandable! For this reason I won’t be showing an image or clip of it for those sensitive to this sort of film, but for those interested just search Un Chein Andalou on YouTube :) I have always felt very drawn to this specific part of the piece, mainly for its intensely gory visuals of an eye being sliced open. I’ve always been very drawn to gore and horror within my own artwork and it’s something I find inspiring when I see elements of it with other artists work too.

Towards the end of the lecture it was explained how some people didn’t like surrealism, even Freud didn’t like it. He spent his life deciphering the codes of the unconscious mind so that people could understand themselves better. The thought artists should paint the conscious mind rather than wasting their time painting Freudian symbols such as apples, hats and birds. Although still even to this day, surrealism has had a large impact on culture and society as Breton said Surrealism is not just an art movement, it’s a way of thinking, a way of life, a way of transforming existence.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uPD6okhfGzs

After this segment of the lecture, Julie then went to talk about different theories and methodologies to look at Surrealism through. The first she talked about was Biographical Theory in which you focus on the biography of the artist and how the work reflects the artists personal history or personality.

The next one to be talked about was Psychoanalytical Theory which is the method in which you analyse a physic or emotional phenomena. Psychoanalysis has been used at various times to address the subject matter or content of individual artworks; he relationship of artworks to the artist; the relationship of the viewer to the piece and the nature of creativity itself.

The last to be talked about was Reception Theory in which it argues that the viewer actively completes the work of art. Gombrich described this as ‘the beholders share’ – the viewer brings their own stock of images and experiences when they view the artwork.

One of the first pieces to be shown within the lecture was a piece by James Durden called Summer in Cumberland painted in 1925. When talking about this piece I realised Julie using reception theory when she started to tie in her own experiences of being a female when she commented on how the women depicted inside the house are trapped behind a wall; that wall being physically represented by the wall and windows of the house. They are shown as being enraptured by the domesticity of life as they are shown sat together drinking tea, dressed up nicely and seemly have nothing better to do than to talk to the cat. Meanwhile, the only man depicted in the painting is shown looking into the house freely while all the landscape is outside, belonging to the same side as the boy while the women are separated from the outside by a wall.

Another piece shown within this lecture was the work of Leonora Carrington. In the beginning of this segment Julie showed an interview with Carrington in which she was asked about her work. She then replied with “You’re trying to intellectualize something, desperately, and you’re wasting your time. That’s not a way of understanding, to make a sort of mini-logic, I’ve never understood that role.” When I heard her say this within the interview, I felt myself having such a strong connection to her. This is something I’ve had an issue with for a long time when considering my own work, how people always immediately go to the insides of something to try and find meaning or something larger than what it really is. It really bothers me, and I can see how it bothers Carrington too. For this reason, out of respect of Carrington, I wont delve into the meanings behind her work or try and find some intellectual meanings behind it as its clear this isn’t how she intended her work to be seen, especially considering she flat out said it herself. I really respect how she was clear about this, and how she refused to talk about her work at all throughout the interview and instead went to criticize why there needed to be any explanation of it in the first place. I really respect the response of that.

Overall, I found this lecture to be inspiring and intriguing. Although I found it intriguing how I learnt more from a short 5 minuite video breaking down surrealism than I did during the hour and a half lecture about it. Although I know this is just my personal way of learning and it isn’t a criticism of Julie, I loved this lecture and I found it interesting to see how others see surrealism, its just not how I would personally go about learning about this subject.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Disclaimer: Stream of consciousness rant about ecology, trophy hunting, some other depressing shit, and my trademark attempted optimism.

I really want to stay positive and so I try and maintain a healthy balance between staying informed and not obsessing over current affairs. This means I read the news with a grain of salt (and avoid broadcast news), try and view everything with perspective, and research topics before stating my opinion. But occasionally the juxtaposition of information can be...depressing.

I am reading Thomas Friedman’s Hot, Flat, and Crowded and while parts of the book have been difficult to read because he writes like he’s giving a political speech, it has been informative. He makes a compelling case for shifting our economic paradigm, currently based upon using nature as a resource/commodity, towards a more ‘sustainable’ approach where humanity produces more than it consumes. On page 214 he analyzes humanity’s state of progress, along with a quote from California Institute of Technology chemist Nate Lewis. Friedman writes, “We are failing right now. For all the talk of a green revolution, said Lewis, ‘things are not getting better. In fact, they are actually getting worse. From 1990 to 1999, global CO2 emissions increased at a rate of 1.1 percent per year. Then everyone started talking about Kyoto, so we buckled up our belts, got serious, and we showed ‘em what we could do: In the years 2000 to 2006, we tripled the rate of global CO2 emission increases, to an average [increase] for that period of over 3 percent a year!’”

This morning, while eating breakfast, I scrolled through my Google newsfeed and came across the following two articles:

Humans Are Just 0.01% of Life on Earth, But We Still Annihilated The Rest of It

Interior Dept. moves to allow Alaska bear hunting with doughnuts, bacon

It’s important I stop and identify some of my prejudices before climbing on a soapbox. I do not support sport/trophy hunting. I believe it is entirely egotistic and selfish, entirely devoid of empathy. Frankly, I find it disgusting. With that said, I respect subsistence hunters. My freezer is currently full of elk meat, my pantry full of canned tuna and salmon. I support game hunters who do more than just mount a carcass on their wall.

So when I read those two articles, back to back, my heart sunk. Humanity has a chokehold on nature. Why is it necessary to allow hunters to bait with donuts and bacon? Isn’t it already an unfair advantage using a gun? If this were a true sport, wouldn’t the hunter and prey battle on a fair playing field? Because this isn’t a sport. It’s domination. This is an ecological version of the Globetrotters and Generals.

Why, despite evidence to the contrary, must humanity continue to subjugate nature? I can’t help but feel humanity wants to be cataclysmic. There’s this self-destructive force beneath the surface of humanity. Like Oppenheimer said as he witnessed the atomic bomb, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” Do we desire to be the catalyst for destruction? I can’t help but feel if there is a metaphysical reckoning someday/sometime, the evidence will be stacked so heavily against us those words may ring true for all time.

Thomas Friedman’s book was written in 2007. Emissions have not slowed since and the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere continues to accumulate at an accelerating rate. The majority of the world believes this is an issue, yet we are so infuriatingly obsessed with ourselves that we’ve done almost next to nothing to address the issue and instead we continue to exacerbate the problem.

I say next to nothing because, like everything in life, there’s another side to this coin. One of the reasons for our ramped up environmental degradation would be an increase in the standard of living for world inhabitants (and yes, industrialization, consumerism, and the international corporate-state are variables in this increase). While there are numerous social issues around the world that still need to be addressed, the sanctity of human life is being reanalyzed worldwide. This, while it doesn’t seem like much, is still progress. Homicide rates have dropped substantially the last 600 years, bottoming out at the beginning of the 20th century (which may have implications concerning the world’s carrying capacity). When available, medical advances have increased life-expectancy. And all of this has happened while populations grow exponentially, proving (for now) that collectively humanity is getting along better than ever before.

This means there’s hope. My issue, much like the rest of my fellow humans’, is a matter of perspective. In a matter of 24 hours my worldview became darkened because I lost sight of the accomplishments of human collaboration. My own life, made possible by medical advancements (specifically penicillin), testifies to human ingenuity and ability to address issues on a global and grand scale. So how do I help address these issues without either burying my head or allowing the enormity of the issue bury me? By maintaining perspective, seeking out alternative information, and allowing myself time to tune out.

Case in point, rather than simply deregulate laws, we could attempt a wildlife management technique that could increase biodiversity, boost local economies, and still allow trophy hunting. Without stooping to baiting an animal with bacon and donuts.

Honestly, when I began this rant I had no idea where it would lead. Luckily I became engrossed in my work and was able to think about it before returning. I need to also stress the last piece of advice: tune out. It is so important to occasionally tune out. New information presents itself daily and a healthy and recharged brain will be much better at processing it than a tired and sad one.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Here’s who is winning (and losing) during Q1 earnings seasons so far

The Street was bracing for a mixed earnings season. While the impact of the coronavirus has, in many cases, been immediate and dire, corporate earnings for the first quarter are on a lag. “Two-plus of the three months were pretty decent,” says Charles Schwab chief investment strategist Liz Ann Sonders, making earnings for the quarter as a whole “not terribly relevant.”

So far, roughly half of companies have reported. According to a Refinitiv note on Wednesday, there have been 90 negative EPS preannouncements issued by S&P 500 companies, versus 42 positive ones. But much like the GDP report for the first quarter, which came in at -4.8%, first-quarter earnings won’t “tell you all that much about the depth and scope of the impact of the lockdowns,” suggests LPL Financial equity strategist Jeff Buchbinder.

Most estimates show that year-over-year earnings growth for the quarter is down about 15% or 16%, and BofA Global Research noted on Wednesday that based on actual values and the latest consensus estimates, “[year-over-year] revenue growth [is] –0.5%.” For those who have already reported, earnings and sales growth came in “10.9% and 0.4% weaker than expected at the start of the season, respectively, while earnings growth ex-financials has surprised to the upside by 2.5%,” according to BofA research.

But the picture is extremely murky, given the unprecedented business shutdown. According to BofA Global Research on Monday, about 100 companies in the S&P 500 suspended guidance. Yet a large portion of companies in the S&P 500 haven’t been issuing quarterly guidance for a while, even pre-coronavirus, and Schwab’s Sonders suggests the slew of companies withdrawing or not issuing guidance now will only accelerate that trend even after the crisis is largely over.

Instead of guidance numbers, “what I think is most important to try to glean from commentary on calls is what the more macro implications are,” Sonders tells Fortune. Alternatively, she suggests taking note of “What does your balance sheet look like? Do you have cash flows to stay afloat for x period of time? Have you started to lay workers off? If you have, are they furloughed or permanent layoffs? Have you taken government assistance?”

Meanwhile, LPL’s Buchbinder is not suggesting investors look on the sunny side. In fact, he believes investors should watch for “credible downside risk estimates” from companies.

“Investors are looking for comfort: How bad is this going to get in the second quarter?” he says. “The big question, though, is where’s the trough? The companies that can give people an idea of where that trough is are going to perform better.” So far, it’s the big tech names that are doing just that, he says.

Looking back, full-year 2020 earnings estimates were close to $180 earnings per share to start the year. Now, the most optimistic projections are $132. Both Sonders and Buchbinder think those earnings estimates need to come down further still (Sonders estimates it will be around $100 when all is said and done).

Yet perhaps more than ever, strategists note there’s a big gap between winners and losers, and the first-quarter earnings season only emphasizes the “stock-pickers market” we’re in, says Buchbinder.

Winners

Tech has obviously been hot, even before the coronavirus. But now, Sonders suggests there is even “more dispersion in terms of the prospects for individual companies, even within the same sector.”

A couple standouts?

Microsoft surprised the Street on Wednesday, beating earnings per share estimates of 1.26, reporting 1.40. Revenue, meanwhile, topped $35 billion (also above expectations), driven in part by the company’s strong cloud business. Wedbush analyst Dan Ives wrote that the “[work from home] and COVID-19 environment [is] another catalyst driving Azure/Office 365 growth,” as Azure revenue growth was “robust” at 59%. The analyst also raised his price target from $210 to $220 per share.

Another tech name that (happily) surprised investors on Wednesday was Facebook. The company posted revenues of $17.7 billion (versus the $17.4 billion estimate), up almost 18% from the first quarter of 2019, and saw 2.6 billion monthly active users (higher than expected). Yet in comments that are starting to sound very familiar to analysts this season, Facebook’s CFO David Wehner told CNBC that “[the] outlook is really uncertain. We have a really cautious outlook on how things are going to develop.”

Of course, Tesla was a stock many investors had their eye on, having traded up over 200% in the past year. The Elon Musk–led company managed to post a profit in the first quarter at $16 million, also reporting 1.24 adjusted earnings per share versus an estimated loss of 0.36 earnings per share. Yet Tesla also had negative free cash flow of $895 million—jeopardizing its previously stated goal of getting free cash-flow positive for 2020.

Alphabet missed earnings estimates, reporting $9.87 per share, but beat revenue estimates, reporting $41.2 billion on Tuesday—up 13% from the previous year. Yet investors were somewhat encouraged that, despite a drop in ad revenue in March, execs told analysts, “Based on our estimates from the end of March through last week for Search, we haven’t seen further deterioration in the percentage of year-on-year revenue declines” in April.

For the Street, Twitter’s earnings fell somewhere between a win and a loss: The company beat earnings estimates, reporting earnings of 0.11 per share versus the 0.10 estimate on Thursday before market open, but the stock quickly traded down some 7% by midday on discouraging remarks about a slowdown in advertising revenue. While the company eked out an earnings beat, Twitter also didn’t provide guidance for the second quarter, and is suspending full-year guidance.

Even hotly anticipated Amazon earnings fell into a vein similar to Twitter’s: The coronavirus staple stock missed estimates on earnings but beat revenue expectations, posting $75.5 billion. Investors were dismayed after markets closed on Thursday, trading the stock down around 5% in after-hours trading, after the company announced it plans to spend its entire estimated $4 billion operating profit in the second quarter on coronavirus-related expenses. Yet cloud computing and online shopping were bright spots for Amazon, as the company saw Amazon Web Services revenue top $10 billion. “COVID’s impact accelerates the secular shift to e-commerce [U.S. e-commerce represents 12% of retail sales], and Amazon is well positioned to continue taking share,” Oppenheimer analysts wrote on Monday.

Losers

LPL’s Buchbinder suggests that “essentially all of the [overall earnings] misses came from the big banks” this time around.

JPMorgan kicked off its first-quarter earnings with a largely disappointing show, reporting earnings per share of 0.78 cents, missing the 1.84 estimate, while profits dove 69%. One ominous point was the bank’s $6.8 billion reserved for loan loss provisions. Perhaps the only bright spot was the bank’s record trading division revenue, up 32% to $7.2 billion.

Wells Fargo also disappointed, posting earnings per share of just 0.1 cent, versus a 0.33 cent estimate. The bank set aside some $3.1 billion for loan losses as well.

Bank of America hasn’t fared much better, reporting a first-quarter profit decline of 45% to $1.79 billion for its consumer banking business. The bank reported EPS of 0.40 cents a share, versus 0.46 cent estimates. Of note, loan losses would only mount this year, potentially continuing into 2021, CFO Paul Donofrio told analysts. To boot, the bank also set $3.6 billion aside for loan-loss reserves for the quarter, in line with peers JPMorgan and Wells Fargo.

One company feeling the brunt of global shutdowns is McDonald’s. The company reported that earnings fell 17% in the first quarter, missing estimates. The global fast-food chain also withdrew its 2020 outlook and long-term forecast, issued back in February, owing to the uncertainty surrounding the evolving coronavirus environment worldwide.

McDonald’s CEO Chris Kempczinski warned analysts: “We expect the second quarter as a whole to be significantly worse than what we experienced for the full month of March.”

Given the way projections are heading overall, he’ll certainly have company.

More must-read finance coverage from Fortune:

—Latest round of unemployment claims puts real jobless rate near Great Depression peak

—Buccaneers of the basin: The fall of fracking—and the future of oil

—Cybercriminals adapt to the coronavirus faster than the A.I. cops hunting them

—3 ways COVID-19 impacted Microsoft’s latest earnings

—Inside the chaotic rollout of the SBA’s PPP loan plan

—Listen to Leadership Next, a Fortune podcast examining the evolving role of CEOs

—WATCH: Why the banks were ready for the financial impact of the coronavirus

Subscribe to Fortune’s Bull Sheet for no-nonsense finance news and analysis daily.

Source link

Tags: 2020 earnings, alphabet earnings, bank earnings, coronavirus, coronavirus earnings, earnings, earnings season, facebook earnings, Heres, Losing, microsoft earnings, Q1, Q1 earnings, Seasons, winning

from WordPress https://ift.tt/3d84RcC

via IFTTT

0 notes

Link

Technological progress has eradicated diseases, helped double life expectancy, reduced starvation and extreme poverty, enabled flight and global communications, and made this generation the richest one in history.

It has also made it easier than ever to cause destruction on a massive scale. And because it’s easier for a few destructive actors to use technology to wreak catastrophic damage, humanity may be in trouble.

This is the argument made by Oxford professor Nick Bostrom, director of the Future of Humanity Institute, in a new working paper, “The Vulnerable World Hypothesis.” The paper explores whether it’s possible for truly destructive technologies to be cheap and simple — and therefore exceptionally difficult to control. Bostrom looks at historical developments to imagine how the proliferation of some of those technologies might have gone differently if they’d been less expensive, and describes some reasons to think such dangerous future technologies might be ahead.

In general, progress has brought up unprecedented prosperity while also making it easier to do harm. But between two kinds of outcomes — gains in well-being and gains in destructive capacity — the beneficial ones have largely won out. We have much better guns than we had in the 1700s, but it is estimated that we have a much lower homicide rate, because prosperity, cultural changes, and better institutions have combined to decrease violence by more than improvements in technology have increased it.

But what if there’s an invention out there — something no scientist has thought of yet — that has catastrophic destructive power, on the scale of the atom bomb, but simpler and less expensive to make? What if it’s something that could be made in somebody’s basement? If there are inventions like that in the future of human progress, then we’re all in a lot of trouble — because it’d only take a few people and resources to cause catastrophic damage.

That’s the problem that Bostrom wrestles with in his new paper. A “vulnerable world,” he argues, is one where “there is some level of technological development at which civilization almost certainly gets devastated by default.” The paper doesn’t prove (and doesn’t try to prove) that we live in such a vulnerable world, but makes a compelling case that the possibility is worth considering.

Bostrom is among the most prominent philosophers and researchers in the field of global catastrophic risks and the future of human civilization. He co-founded the Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford and authored Superintelligence, a book about the risks and potential of advanced artificial intelligence. His research is typically concerned with how humanity can solve the problems we’re creating for ourselves and see our way through to a stable future.

When we invent a new technology, we often do so in ignorance of all of its side effects. We first determine whether it works, and we learn later, sometimes much later, what other effects it has. CFCs, for example, made refrigeration cheaper, which was great news for consumers — until we realized CFCs were destroying the ozone layer, and the global community united to ban them.

On other occasions, worries about side effects aren’t borne out. GMOs sounded to many consumers like they could pose health risks, but there’s now a sizable body of research suggesting they are safe.

Bostrom proposes a simplified analogy for new inventions:

One way of looking at human creativity is as a process of pulling balls out of a giant urn. The balls represent possible ideas, discoveries, technological inventions. Over the course of history, we have extracted a great many balls—mostly white (beneficial) but also various shades of grey (moderately harmful ones and mixed blessings). The cumulative effect on the human condition has so far been overwhelmingly positive, and may be much better still in the future. The global population has grown about three orders of magnitude over the last ten thousand years, and in the last two centuries per capita income, standards of living, and life expectancy have also risen.

What we haven’t extracted, so far, is a black ball—a technology that invariably or by default destroys the civilization that invents it. The reason is not that we have been particularly careful or wise in our technology policy. We have just been lucky.

That terrifying final claim is the focus of the rest of the paper.

One might think it unfair to say “we have just been lucky” that no technology we’ve invented has had destructive consequences we didn’t anticipate. After all, we’ve also been careful, and tried to calculate the potential risks of things like nuclear tests before we conducted them.

Bostrom, looking at the history of nuclear weapons development, concludes we weren’t careful enough.

In 1942, it occurred to Edward Teller, one of the Manhattan scientists, that a nuclear explosion would create a temperature unprecedented in Earth’s history, producing conditions similar to those in the center of the sun, and that this could conceivably trigger a self-sustaining thermonuclear reaction in the surrounding air or water. The importance of Teller’s concern was immediately recognized by Robert Oppenheimer, the head of the Los Alamos lab. Oppenheimer notified his superior and ordered further calculations to investigate the possibility. These calculations indicated that atmospheric ignition would not occur. This prediction was confirmed in 1945 by the Trinity test, which involved the detonation of the world’s first nuclear explosive.

That might sound like a reassuring story — we considered the possibility, did a calculation, concluded we didn’t need to worry, and went ahead.

The report that Robert Oppenheimer commissioned, though, sounds fairly shaky, for something that was used as reason to proceed with a dangerous new experiment. It ends: “One may conclude that the arguments of this paper make it unreasonable to expect that the N + N reaction could propagate. An unlimited propagation is even less likely. However, the complexity of the argument and the absence of satisfactory experimental foundation makes further work on the subject highly desirable.” That was our state of understanding of the risk of atmospheric ignition when we proceeded with the first nuclear test.

A few years later, we badly miscalculated in a different risk assessment about nuclear weapons. Bostrom writes:

In 1954, the U.S. carried out another nuclear test, the Castle Bravo test, which was planned as a secret experiment with an early lithium-based thermonuclear bomb design. Lithium, like uranium, has two important isotopes: lithium-6 and lithium-7. Ahead of the test, the nuclear scientists calculated the yield to be 6 megatons (with an uncertainty range of 4-8 megatons). They assumed that only the lithium-6 would contribute to the reaction, but they were wrong. The lithium-7 contributed more energy than the lithium-6, and the bomb detonated with a yield of 15 megaton—more than double of what they had calculated (and equivalent to about 1,000 Hiroshimas). The unexpectedly powerful blast destroyed much of the test equipment. Radioactive fallout poisoned the inhabitants of downwind islands and the crew of a Japanese fishing boat, causing an international incident.

Bostrom concludes that “we may regard it as lucky that it was the Castle Bravo calculation that was incorrect, and not the calculation of whether the Trinity test would ignite the atmosphere.”

Nuclear reactions happen not to ignite the atmosphere. But Bostrom believes that we weren’t sufficiently careful, in advance of the first tests, to be totally certain of this. There were big holes in our understanding of how nuclear weapons worked when we rushed to first test them. It could be that the next time we deploy a new, powerful technology, with big holes in our understanding of how it works, we won’t be so lucky.

We haven’t done a great job of managing nuclear nonproliferation. But most countries still don’t have nuclear weapons — and no individuals do — because of how nuclear weapons must be developed. Building nuclear weapons takes years, costs billions of dollars, and requires the expertise of top scientists. As a result, it’s possible to tell when a country is pursuing nuclear weapons.

Bostrom invites us to imagine how things would have gone if nuclear weaponry had required abundant elements, rather than rare ones.

Investigations showed that making an atomic weapon requires several kilograms of plutonium or highly enriched uranium, both of which are very difficult and expensive to produce. However, suppose it had turned out otherwise: that there had been some really easy way to unleash the energy of the atom—say, by sending an electric current through a metal object placed between two sheets of glass.

In that case, the weapon would proliferate as quickly as the knowledge that it was possible. We might react by trying to ban the study of nuclear physics, but it’s hard to ban a whole field of knowledge and it’s not clear the political will would materialize. It’d be even harder to try to ban glass or electric circuitry — probably impossible.

In some respects, we were remarkably fortunate with nuclear weapons. The fact that they rely on extremely rare materials and are so complex and expensive to build makes it far more tractable to keep them from being used than it would be if the materials for them had happened to be abundant.

If future technological discoveries — not in nuclear physics, which we now understand very well, but in other less-understood, speculative fields — are easier to build, Bostrom warns, they may proliferate widely.

We might think that the existence of simple destructive weapons shouldn’t, in itself, be enough to worry us. Most people don’t engage in acts of terroristic violence, even though technically it wouldn’t be very hard. Similarly, most people would never use dangerous technologies even if they could be assembled in their garage.

Bostrom observes, though, that it doesn’t take very many people who would act destructively. Even if only one in a million people were interested in using an invention violently, that could lead to disaster. And he argues that there will be at least some such people: “Given the diversity of human character and circumstance, for any ever so imprudent, immoral, or self-defeating action, there is some residual fraction of humans who would choose to take that action.”

That means, he argues, that anything as destructive as a nuclear weapon, and straightforward enough that most people can build it with widely available technology, will almost certainly be repeatedly used, anywhere in the world.

These aren’t the only scenarios of interest. Bostrom also examines technologies that would drive nation-states to war. “A technology that ‘democratizes’ mass destruction is not the only kind of black ball that could be hoisted out of the urn. Another kind would be a technology that strongly incentivizes powerful actors to use their powers to cause mass destruction,” he writes.

Again, he looks to the history of nuclear war for examples. He argues that the most dangerous period in history was the period between the start of the nuclear arms race and the invention of second-strike capabilities such as nuclear submarines. With the introduction of second-strike capabilities, nuclear risk may have decreased.

It is widely believed among nuclear strategists that the development of a reasonably secure second-strike capability by both superpowers by the mid-1960s created the conditions for “strategic stability.” Prior to this period, American war plans reflected a much greater inclination, in any crisis situation, to launch a preemptive nuclear strike against the Soviet Union’s nuclear arsenal. The introduction of nuclear submarine-based ICBMs was thought to be particularly helpful for ensuring second-strike capabilities (and thus “mutually assured destruction”) since it was widely believed to be practically impossible for an aggressor to eliminate the adversary’s boomer [sic] fleet in the initial attack.

In this case, one technology brought us into a dangerous situation with great powers highly motivated to use their weapons. Another technology — the capacity to retaliate — brought us out of that terrible situation and into a stabler one. If nuclear submarines hadn’t developed, nuclear weapons might have been used in the past half-century or so.

Bostrom devotes the second half of the paper to examining our options for preserving stability if there turn out to be dangerous technologies ahead for us.

None of them are appealing.

Halting the progress of technology could save us from confronting any of these problems. Bostrom considers it and discards it as impossible — some countries or actors would continue their research, in secrecy if necessary, and the outrage and backlash associated with a ban on a field of science might draw more attention to the ban.

A limited variant, which Bostrom calls differential technological development, might be more workable: “Retard the development of dangerous and harmful technologies, especially ones that raise the level of existential risk; and accelerate the development of beneficial technologies, especially those that reduce the existential risks posed by nature or by other technologies.”

To the extent we can identify which technologies will be stabilizing (like nuclear submarines) and work to build them faster than building dangerous technologies (like nuclear weapons), we can manage some risks in that fashion. Despite the frightening tone and implications of the paper, Bostrom writes that “[the vulnerable world hypothesis] does not imply that civilization is doomed.” But differential technological development won’t manage every risk, and might fail to be sufficient for many categories of risk.

The other options Bostrom puts forward are less appealing.

If the criminal use of a destructive technology can kill millions of people, then crime prevention becomes essential — and total crime prevention would require a massive surveillance state. If international arms races are likely to be even more dangerous than the nuclear brinksmanship of the Cold War, Bostrom argues we might need a single global government with the power to enforce demands on member states.

For some vulnerabilities, he argues further, we might actually need both:

Extremely effective preventive policing would be required because individuals can engage in hard-to-regulate activities that must nevertheless be effectively regulated, and strong global governance would be required because states may have incentives not to effectively regulate those activities even if they have the capability to do so. In combination, however, ubiquitous-surveillance-powered preventive policing and effective global governance would be sufficient to stabilize most vulnerabilities, making it safe to continue scientific and technological development even if [the vulnerable world hypothesis] is true.

It’s here, where the conversation turns from philosophy to policy, that it seems to me Bostrom’s argument gets weaker.

While he’s aware of the abuses of power that such a universal surveillance state would make possible, his overall take on it is more optimistic than seems warranted; he writes, for example, “If the system works as advertised, many forms of crime could be nearly eliminated, with concomitant reductions in costs of policing, courts, prisons, and other security systems. It might also generate growth in many beneficial cultural practices that are currently inhibited by a lack of social trust.”

But it’s hard to imagine that universal surveillance would in fact produce universal and uniform law enforcement, especially in a country like the US. Surveillance wouldn’t solve prosecutorial discretion or the criminalization of things that shouldn’t be illegal in the first place. Most of the world’s population lives under governments without strong protections for political or religious freedom. Bostrom’s optimism here feels out of touch.

Furthermore, most countries in the world simply do not have the governance capacity to run a surveillance state, and it’s unclear that the U. or another superpower has the ability to impose such capacity externally (to say nothing of whether it would be desirable).

If the continued survival of humanity depended on successfully imposing worldwide surveillance, I would expect the effort to lead to disastrous unintended consequences — as efforts at “nation-building” historically have. Even in the places where such a system was successfully imposed, I would expect an overtaxed law enforcement apparatus that engaged in just as much, or more, selective enforcement as it engages in presently.

Economist Robin Hanson, responding to the paper, highlighted Bostrom’s optimism about global governance as a weak point, raising a number of objections. First, “It is fine for Bostrom to seek not-yet-appreciated upsides [of more governance], but we should also seek not-yet-appreciated downsides” — downsides like introducing a single point of failure and reducing healthy competition between political systems and ideas.

Second, Hanson writes, “I worry that ‘bad cases make bad law.’ Legal experts say it is bad to focus on extreme cases when changing law, and similarly it may go badly to focus on very unlikely but extreme-outcome scenarios when reasoning about future-related policy.”

Finally, “existing governance mechanisms do especially badly with extreme scenarios. The history of how the policy world responded badly to extreme nanotech scenarios is a case worth considering.”

Bostrom’s paper is stronger where it’s focused on the question of management of catastrophic risks than when it ventures into these issues. The policy questions about risk management are of such complexity that it’s impossible for the paper to do more than skim the subject.

But even though the paper wavers there, it’s overall a compelling — and scary — case that technological progress can make a civilization frighteningly vulnerable, and that it’d be an exceptionally challenging project to make such a world safe.

Sign up for the Future Perfect newsletter. Twice a week, you’ll get a roundup of ideas and solutions for tackling our biggest challenges: improving public health, decreasing human and animal suffering, easing catastrophic risks, and — to put it simply — getting better at doing good

Original Source -> How technological progress is making it likelier than ever that humans will destroy ourselves

via The Conservative Brief

0 notes

Text

Dan Nissen and the Expat Forest Service “Week Wagon” take Spirit of Drag Week

HOT ROD Drag Week 2017, powered by Dodge and presented by Gear Vendors Overdrive

Strictly speaking, the Spirit of Drag Week award is defined as someone who “most demonstrates a do-or-die attitude while helping others, showing good sportsmanship, and spreading the good will of Drag Week,” and this year we’re heavy on the latter. One of our favorite components of Drag Week is the international racing family that has developed over the past 13 years. These folk will do anything for each other across any number of borders and postal codes, and this year’s winner emphasizes how far that good will can spread.

“Montana” Dan Nissen is known for his big-block Chevrolet C20 pickup nearly as well as his selflessness in previous Drag Weeks, and that was apparent for 2017’s race when he introduced the “Week Wagon,” a 1983 Chevrolet Malibu destined for a greater cause—he didn’t know exactly what yet, but the ultimate idea was to auction the rolling chassis toward charity.

This ex–U.S. Forest Service Malibu wagon was actually the second purchase of Dan’s, as the first ended up being better suited to rusting back into the earth than racing. His brother, Mike, found the car listed on Pocatello, Idaho’s Craigslist for $350, and they were able to negotiate the former V6 Malibu wagon to $250 before dragging it back home to Havre, Montana. Even through the patina, the original Forest Service livery was still visible, so the car came with a built-in theme while fulfilling the beater-muscle-car look he liked in Aussie Harry Haig’s “Stevo” Chevelle, the orange-and-rust rapscallion with the turbos out the hood that ran Drag Week the past two years.

The idea was to build it low-buck with spare parts, with the venerable Jeep quick-ratio box and rag jointless steering-shaft upgrades complementing a front-end rebuild with new Speedway Motors control arms and refreshed steering assembly. Out back, Trick Chassis tubular links with heim joints replace the stamped-steel factory arms, which connect to a braced Ford 9-inch that spins 3.50 gears with a spool. Comp Engineering shocks serve duty on all four corners.

Progress started slowly on the wagon, however. Dan’s day job (and often night job) is working on high-voltage power lines as a lineman. It’s an unpredictable gig that often requires him to venture out into the Montana tundra in a bucket truck to save the day, and the conditions in the summer of 2016 meant that the wagon wasn’t going to make it to Drag Week that year. Instead, Dan rode along with Richard Guido, one of his close friends inside and out of Drag Week. Richard is known for his subtly belligerent, stick-shifted 1965 GTO as much as his relentlessly positive attitude (his brother, Bob, is a recipient of the Spirit of Drag Week award—it runs in the family). He’d take the six-hour trip from just north of Calgary, Alberta, to work on the wagon in Montana periodically.

Naturally, things still came to a crunch, and it was again Richard (along with his father) who came down just two weeks before they had to be at tech to help slam the last bits of the Week Wagon together, along with the help of fellow Canadians PJ Nadeau, Matt Blasco, and Dillon Merkl. The refreshed, 496ci big-block Chevy out of his C20 was buttoned up, and the last details for the livery—designed by Jeff Greer of Laser Works of Grand Island, Nebraska, and cut by Dylan Bergos at A Fine Line Auto Body in Malta, Montana—were put together, which playfully mocked Smokey Bear and the U.S. Forest Service. The Week Wagon was given a few miles worth of testing before being packed on a trailer for Cordova, Illinois.

Things looked promising on Day 1 of Drag Week. The wagon had repeated its 10.97 from the previous day’s test-’n’-tune, and Dan was just tinkering with the jetting. However, less than 30 miles into the day’s drive, the Week Wagon’s TH350 began to puke fluid. At first, they resealed the dipstick hoping that would keep the ship from sinking, but it began leaking again as the convoy made it to the first checkpoint at the Blue Moonlight Drive-In. This time, it was clear that the cooler lines were leaking at the transmission fittings, but no one had a wrench that could get into the space. Thankfully for Dan, a local plumber saw his plight and ran 16 miles round trip to grab a set of crowfoot wenches to tighten the fittings. With everything holding tight, the convoy made it to the next hotel by midnight. By Tuesday, things were looking up, with the Week Wagon churning out a respectable 11.03 before winding down the route from Madison to Byron, Illinois, with little drama.

Drag Week’s masochistic reality returned on Wednesday as the mystery TH350’s Second gear decided it was no longer a part of this world, resulting in a beleaguered 12.24 at Byron as the car shifted “like a Powerglide,” according to Dan, with the manual valvebody. Drag Weeker Greg Hurlbutt became a dispatcher for parts and help though social media, and he quickly lined Dan up with Michael and Phillip Roemer of Holeshot Parts and Performance in Waukegan, Illinois, to open up a two-post lift while simultaneously locating a spare transmission to throw in – these are the same guys who worked together to get Spirit of Drag Week 2017 winner Jeff Oppenheim’s new hood after his fiberglass unit melted when his El Camino caught fire. The Roemers essentially handed Dan and Greg the key to the shop that night, and the crew (consisting of Greg, Jeff, Phillip, Travis Ray, and Steve Haefner) worked with their Canadian cohorts to replace the temperamental TH350 that evening, making it the hotel before 10 pm.

By the time they got to Union Grove on Thursday morning, Dan knew the second transmission was toasty, but at least it had all three gears. Plus, they were back in the low-11s, just a few tenths of Monday’s baby-faced runs; by Drag Week standards, things were certainly looking up for the Week Wagon. Dan had one more drive to Cordova before making his final pass.

After a real night’s meal between Dan and his Canadian compadres, Friday was like a homecoming for the mint-green machine, with one last pass to complete Drag Week before auctioning the car to its new owner. The Week Wagon’s cause is supporting someone who’s a part of the Drag Week family—without having raced it. Scott Taylor, an Australian magazine editor who writes for Street Machine (and hosts Drag Challenge, a Down Under version of our hell week), is a good friend of the HRM staff and Drag Week racers after having covered the race for a number of years.

When Dan found out Scott was in need of a specialized van for his son, Alex, who suffers from cerebral palsy, he decided reach out to Scott and offer the Week Wagon as a charity program. Dan saw it as the ultimate way to spread Drag Week’s goodwill beyond hurling transmissions and engines back together. As soon as Dan posted the auction rules on the Facebook page he’d been running for the build, the infamous Harry Haig stepped in almost immediately. He refused to bid, instead offering cash on the spot for the car. In a sense, the Week Wagon came full circle: Dan was inspired by the beater bonanza enjoyed by Harry and his gang of Aussies while they built their field-found 1969 Chevelle SS for 2015 and 2016, and Harry was paying it forward to his fellow countryman by not only helping out Scott’s family but saving the Malibu as something of a Drag Week loaner for his fellow mates to visit the U.S. with and race.

They bought the Week Wagon for $6,000 before the sun set on Friday’s competition, completing Dan’s mission and cementing the Week Wagon in Drag Week lore. It’ll stay in the U.S., sharing a corner with Stevo the Chevelle at Drag Weeker Dustin Gardner’s shop, King Hot Rod and Restoration in Leavenworth, Kansas. We hear it might return in 2018 huffing some nitrous, but we can’t wait for the match race between Stevo and the Week Wagon next year! Better yet, we can’t wait to see the new Spirit of Drag Week trophy. After 13 years, the first one—featuring the cam from inaugural winner Steve Atwells’s 1968 Dart—has ran out of space and Dan is building one that features Bob Guido’s (Richard’s brother) roadside-swapped cam out of his 1969 Ford Mustang (from the when he won the Spirit of Drag Week in 2013). Not only that, Dan’s planning to build carrying cases for them so that they can travel safely across the world to anyone who watches over them, because that’s the kind of good dude he is.

The post Dan Nissen and the Expat Forest Service “Week Wagon” take Spirit of Drag Week appeared first on Hot Rod Network.

from Hot Rod Network http://www.hotrod.com/articles/dan-nissen-expat-forest-service-week-wagon-take-spirit-drag-week/

via IFTTT

1 note

·

View note