#though that also depends on the iteration of werewolves as well

Text

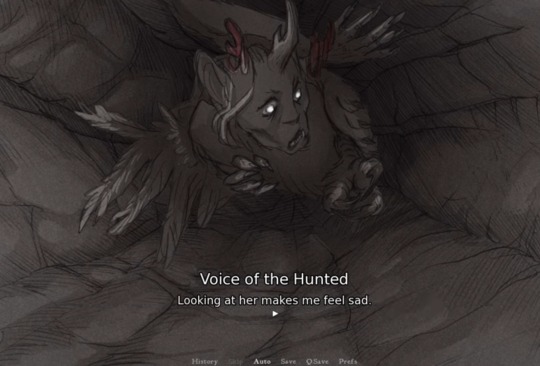

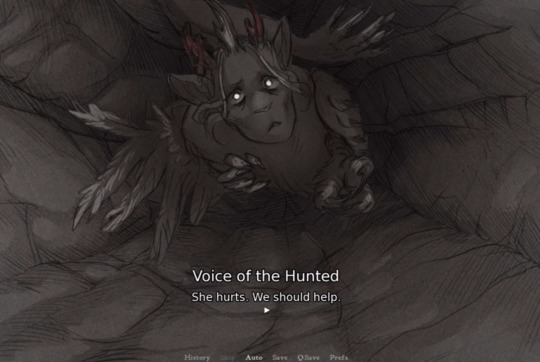

Idk how to explain it, but seeing Voice of the Hunted going from fearing the Princess to wanting to help after seeing her really hits hard. He spent the whole Beast and most of The Den chapter desperately trying to prevent you from being eaten or killed by her

But when he sees what she's become, he feels sympathy for her. Despite his previous fear, he wants to help her instead

#slay the princess#the den#the voice of the hunted#i have such a hard time explaining this game tbh#ik whats going on but idk how to put it into words#i love hunted and stubborn easily my among my favorites w/ paranoid and contrarian#makes me think of werewolves#i mean shes clearly a giant kitty cat but idk makes me think of werewolves for some reason#like theyre big scary beasts but when you truly understand whats happening you feel bad for them#though that also depends on the iteration of werewolves as well

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Vampire Bill - V: One Man Horror Show

This iteration of Bill, still born in the mid 1990s, does not see the world come crashing down around him just before his 18th birthday. Instead, he’s introduced to the supernatural underworld. Vampires, werewolves, and all the fantasy creatures he loved reading about are real.

He becomes a voluntary donor for hungry vampires and builds quite the friend network through that.

He and Frank have a good life; Frank goes to vet school, Bill picks up and goes through various jobs while sometimes supporting himself as an artist. His vampire buddies occasionally support them, offering the couple spare cash during rough patches. Bill becomes well known, both in his natural and supernatural circles, as the guy you go to when you need your car, truck, or anything with a motor fixed. He and Frank live comfortably in a nice house; two bedrooms, two and a half baths, nice little yard, room for visitors. Frank is busy a lot at his vet practice, but Bill doesn’t mind. He sometimes even goes in and helps out.

There’s ups and downs, but life is pretty good until Bill was about 33. A vampire he’d fed a few times before came rolling into town, asking for a meal. Something in his gut knew something bad was going to happen, but Bill shrugged it off as his anxiety and end to feed him.

The vampire ended up taking too much and, in his panic, decided to turn Bill, instead of dealing with the consequences and the guilt of outright killing a human.

Over the next few years, Bill’s life came crashing down around him. He went through the adjustments of living life as a vampire. He finally agreed to turn Frank, who didn’t want to grow old without Bill. They heard horror stories of a rogue monster hunter who seemed to kill monsters for fun, and didn’t care if they suffered. They argued over this; Bill afraid of something happening to Frank, Frank wanting to register with the agency that monitored and cleared monsters.

A couple years later, Frank ran into the rogue hunter. He survived just long enough to get home to Bill.

Devastated over the loss of Frank- and consumed by guilt for being both the passive cause of his death, turning him into a vampire, and the literal one, cutting short a slow and agonizing death- Bill couldn’t stay in one place any more. Between his crushing emotions and increasing pressure to hide the fact he wasn’t aging, he became a trucker. He enjoys it well enough; he’s always like driving, and traveling, and he’s able to stay awake longer than his human colleagues. It pays good, too, although he doesn’t have to worry as much about money any more, as the vampire who turned him looks out for him financially out of guilt.

Sub verse - V: Conundrum

Through unknown means- be it a spot where time is all wobbly, a curse, an adverse affect from a fellow monster, whatever- Bill has been thrown back into the past.

This mostly covers the realm in which he ends up in the 1800s, but can extend to any era.

Specifically for RDR verse, Bill is initially confused for Bill Williamson. The law catches him(whether for Williamsons crimes or for crimes Bill is accused of) and the Van der Linde gang gets wind of this. Due to the similarities between the two Bills, whoever has come to rescue Williamson is too deep in the rescue to turn back by the time they realize that Bill is not Williamson. GENERALLY the rescue takes place in 1895 or so, but for newer members like Sean or Lenny, this can happen closer to in-game events if desired, or he can just be an established member of the gang.

Dutch, being the man he is, sees something in Bill and welcomes him into the gang. RDR verse threads with Bill can take place at any point during all of this; anywhere from before/instead of him being captured by the law, to when he’s a welcome member of the gang.

He’s a hell of a cook and a talented artist. He also has a lot of mechanical know-how, though sometimes struggles to apply it to current technology, and is eerily good at tracking.

Traits of his vampirism:

Although he does need blood, Bill can consume ‘human’ food as well, and especially loves anything with meat or potatoes. He doesn’t do so well when he eats a bunch of plant matter or junk food, but for the most part he’s fine as long as he’s also getting blood.

Garlic makes him sneeze and causes his nose to run, but he can’t give it up. It can also make him jittery out of anxiety.

His reflection does not show in silver mirrors and silver burns to touch- at first it just feels incredibly hot, but if he makes skin contact for too long, it’ll leave a silvery burn mark.

He doesn’t appear on film.

He is incredibly strong and fast, and can keep up with many horses for a stretch.

He’s very agile and can make some impressive jumps and climbs.

His senses are heightened, especially hearing and smell.

He cannot turn into any animals, but he does have the some ability to influence them. How well this goes depends on both the individual animal(a loyal horse is harder to sway than a a mistreated one) as well as the species.

#dont LOOK at me ive been rping since i was lie 11-12 and started out w vampires and stuff#long post#one man horror show headcanons#conundrum headcanons

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

As a Star Trek fan, it’s hard not to get excited about the chance to slip on a virtual reality headset and find yourself manning a station on the bridge of a starship.

That’s what Star Trek Bridge Crew offers players, at least at first. The game, which just launched for Vive, Oculus and PSVR, is an immersive Starfleet sim for up to four players. Aboard the Aegis, players get to take on the roles usually reserved for characters from the long-standing sci-fi franchise, and act out missions similar to those from the 1966 original series and its recent film reboots is an exciting one.

Star Trek Bridge Crew works to envelope players in the unique, specific Star Trek setting as officers with distinct specialties working at various stations on the ship's bridge. Players can choose to be the helm officer who pilots the ship, or they can scan and target other spacecraft and anomalies at the tactical station, or monitor ship systems at engineering; or coordinate them all as the captain.

Each station has a set of controls that players manipulate either with standard controllers or (much more satisfying) motion controls. The helm steers, tactical fires photon torpedoes and phasers, and engineering adjusts power levels to maximize the ship’s effectiveness depending on the situation. As Klingon warbirds or ships in distress appear on the ship’s viewscreen in VR, players use voice chat to coordinate their efforts. Star Trek lines have a tendency to pop out of players’ mouths, like “red alert” and “energizing” and “firing photon torpedoes” and “make it so.”

The way the game captures the Star Trek milieu is note-perfect, and is sure to delight Trekkies. But the key words in the game's title aren't "Star Trek." They're "bridge crew." The game's co-op multiplayer experience is unique and exciting.

The developer Red Storm Entertainment started out by prototyping games with an angle toward replicating something video games often struggle with: deep social interactions between players. But the early iterations the studio was creating were still missing something key -- they were designed to be played on standard TVs and monitors. It wasn’t until the designers started trying multiplayer prototypes in virtual reality that they figured out what it was.

“There was always kind of that missing depth of social interaction,” says senior creative director David Votypka. “And when we took one of those prototypes and put it in VR, and we’re sitting across a table from each other, me and one other developer, just looking around and seeing that person’s head move naturally ... Immediately you're just like, 'wow, that’s another player.' And you immediately feel this social connection that’s just not there in other games.”

"The risk is the ‘cell phone at the dinner table’ problem, where people are focused on their panels, and tune each other out."

Red Storm set out to create a game that was about bringing players into situations that would get them working together. The feeling of presence in virtual reality, the Star Trek setting and Bridge Crew’s cooperation-focused design are all ultimately angled at creating social situations.

“There are a lot of little things we worked into the design to stimulate that interaction,” Votypka explains. "The risk is the ‘cell phone at the dinner table’ problem, where people are focused on their panels, and tune each other out. We've aimed for a mix of working on your station and then coming up for air to discuss and ask questions and make requests of other players.”

Each of Bridge Crew’s stations is designed to rely on the others. The helm can’t make a jump to warp speed unless engineering has charged the engines; tactical can’t target a ship unless the helm has positioned it for targeting and closed range. Votypka said that Red Storm’s major design considerations were finding that balance of giving players enough information individually to make them effective, but still dependent on the other players to get their jobs done. That meant plenty of iteration on the user interface for each station to figure out just how much data to give players in the heat of the moment.

But figuring out how players might actually interact is still something of an open question. The game is designed to mimic what Star Trek fans see on the screen when they watch the shows and movies — but just because everyone follows Captain Kirk’s orders on TV doesn’t mean they’ll listen in the game.

"I think one thing that’s going to be very interesting when the game releases is how much players actually listen to the captain."

“I think one thing that’s going to be very interesting is how much players listen to the captain,” he says. “We tried to design for that specifically, because in the shows and the films, they follow the script, and the script has them doing what they're told. But this is a multiplayer game, so who knows what’s going to happen.”

Red Storm tried to anticipate this. The developers operated on the design philosophy that the captain should be the smartest person in the room, so the game feeds the team’s leader mission-critical information that no one else can get, which helps in decision-making.

But the social interaction element that makes Star Trek Bridge Crew interesting is also the hardest to predict for its creators. Red Storm had a bit of an advantage going into Bridge Crew, though, because it had created another well-received social multiplayer VR game: Werewolves Within. That game has players sitting around a round virtual table, trying to determine who among them is secretly a werewolf. It’s all about social interactions, with players trying to ferret out lies from one another, and the mechanics that allow for secret communications and alliances to develop.

[embedded content]

In both games, an essential part of making those interaction's work was developing players’ sense of presence in the virtual space. Votypka explains how VR helps make social cues, like looking at or pointing at someone, translate through the game, and add layers to interactions that other games aren’t capable of delivering. But in order for those social cues to work, they had to be believable, and mimic the way people interact in the real world.

"VR helps make social cues, like looking at or pointing at someone, translate through the game, and add layers to interactions that other games aren’t capable of delivering."

Motion controls help sell that sense of presence by mimicking the feeling of interacting with virtual objects, like the control panels, in the game. But Red Storm also paid a lot of attention to animation in Star Trek Bridge Crew, to make the in-game characters behave realistically.

“In both games, we do full body avatars, but in Star Trek we do hand tracking on the avatars,” Votypka said. “So we have your head data, which can drive where your head looks, obviously, and where your torso is leaning and so on, so that works very well. And we have your hand data, but we don’t have data of your shoulders, and specifically your elbows. So that’s a limitation that we had to do a lot of tricks to make sure the avatar’s elbows look natural, and didn't get into funky places. Not only for the first-person (view), but a whole other set of tricks for the third person models that the other players see. So in first-person, you can now look out the bottom of your headset and move your elbow, and often times it’ll match exactly where your arm is, but we also had to take into consideration what the third-person model is doing.”

The sense of presence that makes VR so effective for social games like Star Trek Bridge Crew and Werewolves Within can have drawbacks, though. Players can not only refuse to obey orders--they can openly antagonize their fellow Starfleet members. Player griefing is a concern among multiplayer VR game-makers in general — when you’re sharing a space with another player, even a virtual one, elements of griefing can be much more intense.

“Player griefing is something you have to think about it in VR, and social VR particularly,” Votypka said. “So when somebody can lean into your personal space, or put their hand in your face, or what. There’s a sort of physical aspect of griefing somebody else, not just voice anymore or ‘teabagging’ or whatever.”

Dealing with players who might try to ruin the experience of others takes on additional importance for some developers in VR, because the added component of personal space can make those interactions even worse for the player on the receiving end. Red Storm is still working out how to deal with those people, Votypka said. In Werewolves Within, for instance, developers added a mute function that not only silences the voice of an offending player, it also mutes their animations as well. They’re stopped from berating the other player verbally, and they can’t use their presence in VR to pantomime offensively either.

In Star Trek Bridge Crew, Votypka said some of those issues of your presence in VR aren’t as big a concern, because players are positioned around the bridge and are generally pretty far away from each other. And generally, the studio has found that VR encourages people to be polite and nice to one another — likely another element of the fact the game closely approximates feeling like you’re really in a room with other people.

“The vast majority of what we’ve seen and heard in the Werewolves Within community has been player behavior that generally consists of very friendly and positive interactions,” Votypka says. “There are probably several reasons for this, including the current age of VR headset owners skewing to be older, and that players who buy a social VR game are looking to socialize. But we also hypothesize that players may tend to behave more cordially to one another because they feel more like they are face to face with those other people, and therefore may (even subconsciously) behave more along the social norms that guides people in the real world. In traditional games players feel much less attached and present since they are effectively on the other side a flat screen, as opposed to feeling that they are ‘there’ themselves.”

Even though Red Storm has experience with VR games and multiplayer, a lot about how players respond to and interact within Star Trek Bridge Crew still remains to be seen. VR multiplayer is still uncharted territory in many respects, and even with one such game under its belt, Votypka said Red Storm has been surprised about how players interact with each other in virtual worlds.

0 notes