#to over compensate the fact he’s gay? in 2023?

Text

.

#anon#this has nothing to do with hl being together currently#do you not notice the patterns#do you not see how it’s the same everytime?#how his words contradict his actions?#the ice cream sighting#the gallery sighting#the sighting with water involved#then at concerts#a jacket that he always wears when with his ‘so’#it’s a copy of a copy#yet he says he’s a private person? with private relationships?#it doesn’t add up and it’s obvious to see#and he’s doing it why? has he not had his fill? is he not secure in himself?#need a little more money? popularity? fame?#it’s all calculated#‘i thought he only dated white women’ ‘harry i only date white women styles’#(actual comments on twitter dot com)#you know it#to over compensate the fact he’s gay? in 2023?#you wouldn’t see it if he was actually dating someone#and also just so everyone knows#women who participate are also the problem 😊#it takes two and we aren’t going to defend either here#this is all a jumble of thoughts but i think it gets my point across#that is preformative unnecessary and frankly insulting to my intelligence#sorry if you can’t see it that way

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

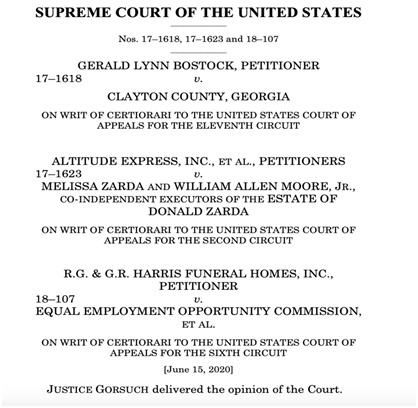

A Battle Of Labels? A Breakdown Of SCOTUS Ruling On LGBTQ Discrimination

By David Glickman, Cornell University Class of 2023

June 19, 2020

On June 15th, in a 6-3 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that employers cannot discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity. The case was responding to three independent cases: Gerald Lynn Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia; Altitude Express, Inc., et al. v. Melissa Zarda and William Allen Moore, Jr.; and R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes, Inc. v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. As the Court explains, Clayton County fired Gerald Bostock, a county employee, shortly after he began participating in a gay softball league, claiming his conduct was “unbecoming.” [2] Altitude Express fired Donald Zarda days after he mentioned being gay. Finally, R. G. & G. R. Harris Funeral Homes fired Aimee Stephens who presented as a male when hired, but later notified the employer that she decided to “live and work full-time as a woman.”[2]The ruling was that discrimination on the bases of sexual orientation and gender identity violates Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which bans discrimination “against any individual with respect to his compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment, because of such individual's race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.” [1]The ruling is a major victory for LGBTQ members seeking equal protection from discrimination at the workplace.

The rationales for the majority and dissenting opinions are interesting as judicial and sociological questions arise. Before dissecting the arguments, it is important to mention that the Justices explicitly note that they are not judging based on their personal stances on the moral issue of discriminating against LGBTQ members. Rather, they repeat that it is their job to judge whether Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits such discrimination. Both the majority and dissenting opinion agree on the basic facts of the case. They conclude that it was neither the intention nor the common understanding of the congress writing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to include sexual orientation or gender identity as protected traits (or as part of sex) in Title VII. The major points of disagreement boil down to judicial philosophy, a so-called battle of labels – a disagreement about whether the relationship between sex and sexual orientation and gender identity are inextricable or not, and whether Title VII is applicable on an individual level or group level.

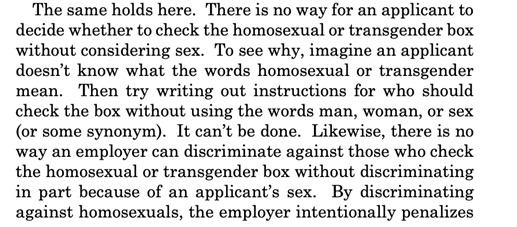

The debate about the judicial philosophy used to rule the case concentrates on textualism, which focuses on “the plain meaning of the text” as understood by “people at the time they were ratified” and “the context in which those terms appear.” [3] It deals with the objective meaning of the text, typically not inquiring into questions about the “intent of the drafters, adopters, or ratifiers” of the law in question. [3] The majority opinion, written by Justice Gorsuch, states that the decision relied on textualism, explaining that “only the written word is the law, and all persons are entitled to its benefit.” [2] He interprets the literal words and consequent standards, ignoring any intentions or expected applications of lawmakers at the time. He explains that “when Congress chooses not to include any exceptions to a broad rule, courts apply the broad rule.” [2]The debate over how to interpret is crucial in the ruling because the rest of the argument would not matter if the intent and expected application of the law were taken into account. In his dissent, Justice Alito Jr. describes the majority ruling as sailing “under a textualist flag,” accusing the Court of ruling by a theory that “courts should ‘update’ old statutes” in order to “better reflect the current values of society.” [2] In the way he views textualism, “it calls for an examination of the social context in which a statute was enacted because this may have an important bearing on what its words were understood to mean at the time of enactment.” [2] In his dissenting opinion, Justice Kavanaugh adds that “Statutory Interpretation 101 instructs courts… to adhere to the ordinary meaning of phrases, not just the meaning of the words in a phrase.” [2]A key aspect of the majority opinion is in fact dissecting phrases and setting standards based on those phrases. The core of the disagreement is the approach to interpreting.

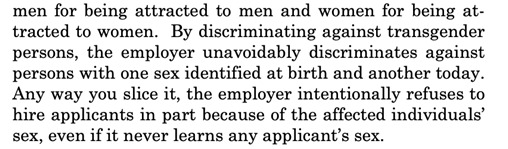

Beyond judicial philosophy, there is a disagreement about the nature of the relationship between sex and sexual orientation and gender identity. The relationship primarily draws on our sociological understanding of sex, sexual orientation, and gender identity. In the view of the majority opinion, “homosexuality and transgender status are inextricably bound up with sex.” [2] Gorsuch elaborates that when an employer discriminates on the basis of sexual orientation, the employer “intends to penalize male employees for being attracted to men and female employees for being attracted to women.” [2] In this view, sexual orientation is defined by its components – the sex of the person and the sex the person they are attracted to. As for gender identity, the majority opinion states that “by discriminating against transgender persons, the employer unavoidably discriminates against persons with one sex identified at birth and another today.” [2]

In both cases, sex plays a factor, reflecting current sociological understandings of sex, sexual orientation, and gender identity. The dissenting opinion argues that the sex and sexual orientation and gender identity are independent since an employer can discriminate against someone who is homosexual or transgender without knowing their sex. The question then boils down to what Alito Jr. describes as a battle of labels – how to label discrimination against LGBTQ members.

The majority opinion labels it as sex discrimination since the expectations of an LGBTQ member of one sex (in terms of attraction and gender expression) are different for someone of the opposite sex (i.e. it is acceptable for a woman to be attracted to man but a problem for a man to be attracted to a man). The dissenting opinion does not label it as sex orientation,only discrimination due to sexual orientation and gender identity since you can discriminate against one without knowing the other. Alito Jr. also argues that discrimination against homosexual and transgender people can be equally applied to both sexes as there are men attracted men and women attracted to women (and men transitioned to women and vice versa) so that the only distinguishing factors are sexual orientation or gender expression, not sex.This leads to a disagreement about whether Title VII applies on the individual level or group level.

Viewing the protections of Title VII as applying on a group level means prohibiting restrictions that only apply to one group. In the case of sex, an example would be prohibiting women to eat salad when not having such a restriction for men. However, in the example, if the employer prohibits both men and women from eating salad, then the restriction did not discriminate between sexes. Viewing the protections as applying on an individual level means that “the employer intentionally relies in part on an individual employee’s sex when deciding to discharge the employee” even if the employer treated men and women the same as a group. [2] The latter view creates a stricter standard of Title VII. The majority justifies the individual view by explaining that the statute repeats the word“individual” multiple times to establish the broader application of the law. This constitutes the but-for causation standard. It describes a situation in which“a particular outcome would not have happened ‘but for’ the purported cause,” requiring the Court“to change one thing at a time and see if the outcome changes.”[2] This loose standard means that sex does not have to be the primary motivating factor, broadening stated protections because of sex.

The three fundamental disagreements – judicial philosophy, the relationship between sex, sexual orientation, and gender identity, and the individual versus group standard for Title VII application – highlight the different legal and sociological views of our time. The implications are yet to be known in this groundbreaking case. Alito Jr. warns of problems arising with conflicts with religious liberties, sports, gendered bathrooms etc. [2] The majority opinion stated that the Court only focused on the question at hand without thought of future consequences. Only time will tell what is to come!

________________________________________________________________

[1] https://www.eeoc.gov/statutes/title-vii-civil-rights-act-1964

[2]https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/19pdf/17-1618_hfci.pdf

[3]https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R45129.pdf

0 notes