Text

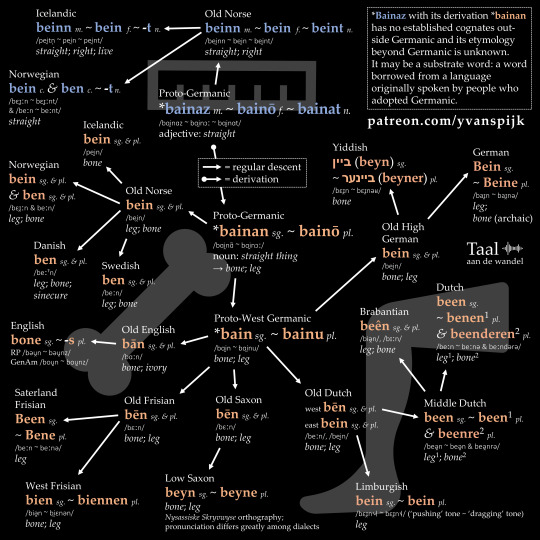

Bone & Bein

The word bone has the same origin as German Bein, Dutch been, and Swedish ben, which mean both 'bone' and 'leg'. These nouns are thought to stem from an adjective meaning 'straight'. It lives on in Icelandic beinn and Norwegian be(i)n 'straight; right'.

57 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The best part of drawing bivalves?

They’re mostly underground, so you don’t have to draw anything. But for those who want to *actually* draw bivalves for #InsertAnInvert, @spissatella helped me prepare these cheat sheets!

—

#InsertAnInvert is a series of invertebrate drawing guides done in collaboration with actual experts (like, literal Dr. Crabs and Dr. Cephalopods and all that) so if you could give them a follow on twitter that’d be swell.

High-res PDFs available for free on my rarely updated Patreon. Absolutely no money required. I just think Patreon is useful for attaching PDFs.

248 notes

·

View notes

Text

this is different. german is similar to english where you get words like rainbow, or football, or what have you. however, polysynthetic languages are different because you can form full clauses/sentences with one “word”. german still has a big emphasis on word order and like, separate articles

for example: he stands in front of the house in english is the same in german- each unit of meaning is its own word. (one of the) word(s) for speed limit in german- Höchstgeschwindigkeit- is a noun. that is just one noun with the meaning “highest speed”. as opposed to @kanikakwaho’s example in the previous post, where something that would be *an entire phrase* in english- his house was good at one time- is one word.

polysynthetic vs isolating languages are on a sliding scale. languages like mandarin are much more isolating, vs many languages from the “americas” which are much more polysynthetic

i love when native words for things are long as shit like blueberry pie being miini-baashkiminasijigani-biitoosigani-badakiingwesijigani-biitooyiingwesijigani-bakwezhigan in ojibwe and hippopotamus being kihci-kispakasakêwi-mistipwâmi-mahkitôni-nîswâpitêwi-atâmipêko-pimâtakâwi-kohkôs in cree

#now: i have not taken morphology yet so this is 1) a bare explanation and 2) may be clouded by memory#languages#linguistics

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Tips I’ve Learned from Relearning my Second First Language

This is really important, to me, and maybe to you, too.

But first, here’s some background info on me and bilingualism in general:

I grew up speaking Japanese and English and started speaking them as a baby at the same time (simultaneous bilingual). Some of you may have learned one after the other (sequential bilingual).

I grew up speaking Japanese because my grandma mostly raised me, and she’s Japanese. So through her, I learned Japanese. This is my heritage language. Another example, a common heritage language in California (USA) is Spanish, and I have friends who grew up speaking Vietnamese and Tagalog.

By definition (for ease, through Wikipedia), a heritage language is is a minority language (either immigrant or indigenous) learnt by its speakers at home as children, but never fully developed because of insufficient input from the social environment.

People who speak a heritage language range in their skillset: some speakers are more fluent than others, and some can only understand. Some may know how to read and write, but many don’t. Everyone is different.

The past couple months, at 25 years old, I decided I wanted to start trying to learn Japanese again. Before starting to study it more actively, I could understand Japanese pretty easily, minimal ability to speak, read, and write (hiragana was the easiest, followed by katakana and some kanji). When I was younger, I attended Japanese school on Saturdays, which is where I learned to read and write.

I had tried many many many times before to learn Japanese again, but I failed every time.

Here are some things I wish I would have realized earlier:

1. You can’t rely on passive skills to study if you want to improve your active skills

Passive skills: Listening comprehension, reading

Active skills: Speaking, writing

Active skills focus on the production of language. For the longest time I wasn’t improving these skills because I thought that I could improve them by listening to more things in Japanese: TV shows, songs, YouTube videos, listening to my family speak.

But why would that work if I’ve been listening to my grandma speak to me in Japanese for 25 years of my life and I didn’t gain any active skills from that?

In order to gain improve your active skills, you have to practice by using your active skills.

I know, if you don’t speak a heritage language and are reading this, you might think DUH! I learned Portuguese and the only way to get good at speaking it is to speak it. I don’t think I realized this was the case with my Japanese because I already had an “in.” But this still applies. I had to speak and write more in order to be able to, well, speak and write more.

2. You have to try

You grew up speaking another language. It’s a special gift. But if you’re lacking in certain skills, you still have to work to try and strengthen those skills.

A couple years ago, I went back to study at my Japanese school as an adult because I thought it would help. It kind of did, but not really…

I TRICKED MYSELF into thinking I understood all the material because I could understand everything the teacher was saying, when in reality I wasn’t able to retain the kanji or the syntactic structures I was learning.

By tricking myself into THINKING I knew things, I sabotaged my own learning experience.

You have to try, and you have to really want to learn it because already knowing parts of the language have the potential to hold you back.

3. Use what gave you the language to your advantage

Don’t “use” them, but you know what I mean.

For the longest time (childhood into recent adulthood), I was too embarrassed to use Japanese with my mom and grandma. I would only routinely use a select amount of phrases that I felt comfortable using, even if my grandma was speaking to me in Japanese.

My mom would always say “You have the best resources around you, practice your Japanese while you can.”

And while sometimes what parents say can be annoying, my mom was right.

But it took a HUGE change in my life to realize this and take action.

When I was 23, my grandma went back to live in Japan. It was an emotional and difficult time for me because I was so used to having her around. While she was living with my family, we learned to communicate in a mix of Japanese-English, and I expressed my gratitude for her by doing housework for her, or buying her things at the grocery store or brought her desserts after going out to eat with friends.

But her moving across the world meant that I couldn’t do these things anymore. A couple days before her departure, I decided that I would try and write her a letter in Japanese and slip it in her backpack for when she arrived in Japan.

Let me tell you, I had THE MOST difficult time writing that letter. I couldn’t express how much appreciated her because my Japanese sucked. And I hated that I couldn’t tell her that in her own language.

So after she moved to Japan, I started to write her letters–*practicing those active skills though!!!

By being able to write letters with my grandma, not only was I practicing my Japanese, but I was creating a relationship with my grandma that I had never had before. I knew that I would regret it if I didn’t talk to her more before she’s gone. Which is sad, but it’s reality.

And let me tell you. I’ve improved a lot.

I can think in Japanese now. It may not be perfect, but I know how to structure my sentences. Words are coming more easily to my brain now. I can communicate with my grandma.

4. It’s never too late

I considered late high school/early college the prime of my language learning career. I got myself to a decent level of Spanish, I learned Portuguese, I took classes in Mandarin and French.

But for some reason, I thought my Japanese was always DOOMED because it was just way. too. hard. for. me. to. learn.

Japanese is hard. But it’s not impossible.

I realized that at 25. It’s never too late to learn a language, but it’s also never too late to try and relearn a language you were familiar with before.

Just take it one step at a time.

I always thought Japanese was overwhelming because I KNEW how difficult it was. I thought about everything–kanji, onyomi and kunyomi, all the sentence structures and everything all at once. This freaked me out and made me think I could never learn it.

But if you learn it little by little, it’s not as overwhelming.

#

That’s pretty much all the major points of things I wish I realized earlier when it came to studying Japanese.

Language is something I’ve been interested in for a long time in terms of academics, so Japanese is naturally, important to me as a language. For other heritage language speakers, it might be more of the food that’s important, or cultural aspects, or other parts of their heritage that is important.

Everyone is different.

But this was for you, heritage language speaker, if you needed a little push.

741 notes

·

View notes

Text

Inspired by Poul Anderson’s “Uncleftish Beholding” and a short discussion of “wittingship” (a “pure” Germanic English neologism for “science”) that I had yesterday, I “translated” the intro of the Wikipedia article on Linguistics into “pure” Germanic English, intended to be absent of loanwords before 1066, but with Modern English form. Now you know what Wikipedia might’ve looked like if William the Conquerer hadn’t conquered.

Tonguecraft is the wittingshippish learning of mannish speech, or tongues. Tonguecraft can be broadly broken into three gatherings or underfields of learning: speech shape, speech meaning, and speech in withhanging. The earliest known workings in downwritten tonguecraft were bestowed by Pāṇini about 500 BSR (Before the Shared Reckoning), with his uploosening of Sanskrit in Ashtadhyayi.

Keep reading

137 notes

·

View notes

Photo

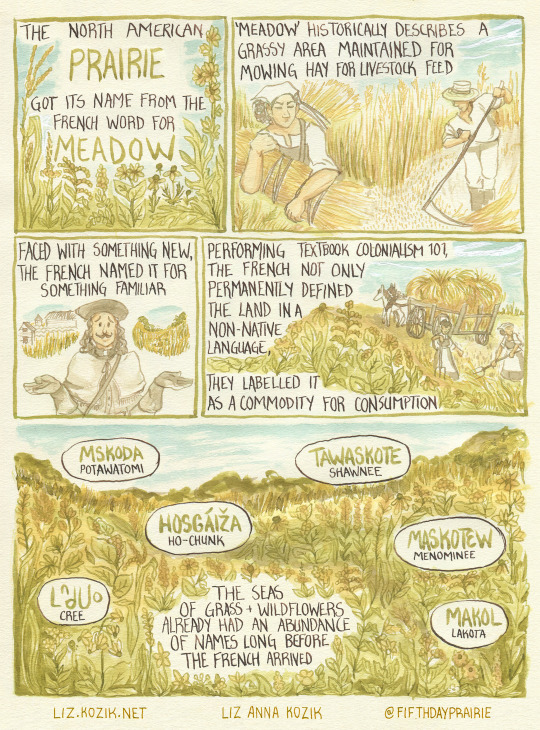

Let’s talk about prairie, history, and language. For communities so focused on “native plants”/”native gardening”/etc there’s so little acknowledgement or engagement with indigenous Americans and their history.

When we talk about science, there’s a baseline assumption of objectivity. Science is Truth, something apart from messy cultural ideas. The reality is, culture and all it’s messes bleed into science, like here in ecology. We gotta be conscious of the histories we inherit in science.

15K notes

·

View notes

Text

✨With most schools, colleges and unis closed around the globe and most studyblr students now having school at home I thought I would create a challenge to help everyone stay focused and productive and also to connect with people so even though most people are self-isolating, we don’t feel lonely✨

✨Info✨

Because no one really knows when we’re going to be able to go back to schools and I know it will depend very much on where you live, I’m going to do a month of daily ‘challenges’ starting on Monday 23rd March 2020 but if the quarantine keeps going I’ll try to add as the weeks/months go on

I want to see what y’all are posting so please use the tag #2020 quarantine challenge and I’ll track this tag and reboot as much as possible!

On this note, I will reblog basically everything even if you don’t think it is ‘aesthetic’ cause I love seeing how everyone does their notes and stuff so please get involved 💕

✨Week 1 - Questions✨

Mon - Have you made a study schedule to help you study at home?

Tue - How are you being taught your lessons? (google classroom, teams etc.)

Wed - What’s your favourite study snack?

Thu - How are you keeping active?

Fri - What is your favourite subject/topic to study at the moment?

Sat - Where in your house is your favourite place to study?

Sun - What are you doing to relax?

✨Week 2 - Pictures✨

Mon - Take a picture of your desk/study space

Tue - Take a picture of the book you are currently reading

Wed - Take a picture of your most colourful notes

Thu - Take a picture of the pens/highlighters that you could not live without

Fri - Take a picture of the view outside your window

Sat - Take a picture of a meal you’ve cooked or something you’ve baked

Sun - Take a picture of some of your art or doodles

✨Week 3 - Questions✨

Mon - What is your favourite food to cook or prepare?

Tue - If you could go anywhere in the world for a week, where would you go?

Wed - What is your biggest goal for this year? Have you done anything so far to achieve this?

Thu - What is the song that makes you happy no matter what?

Fri - What is your favourite TV programme at the moment (on Netflix etc)?

Sat - Where is your favourite place in the world (eg a city you’ve been to, a restaurant, or a particular hiking spot)?

Sun - What is your favourite joke?

✨Week 4 - Tips advice ✨

Mon - What is your biggest tip for staying focused?

Tue - What is your biggest tip for not getting cabin fever?

Wed - What would be your advice to you from five years ago?

Thu - What is the best advice you’ve ever been given (e.g. from a teacher of friend)?

Fri - What is your biggest tip for organising your study space/study materials?

Sat - What is your best tip on how to relax?

Sun - What is you biggest tip to someone starting to learn your major/favourite subject/degree?

✨This is the first month but I might add to this later as the quarantine continues. Let’s all support each other through this difficult time✨

4K notes

·

View notes

Photo

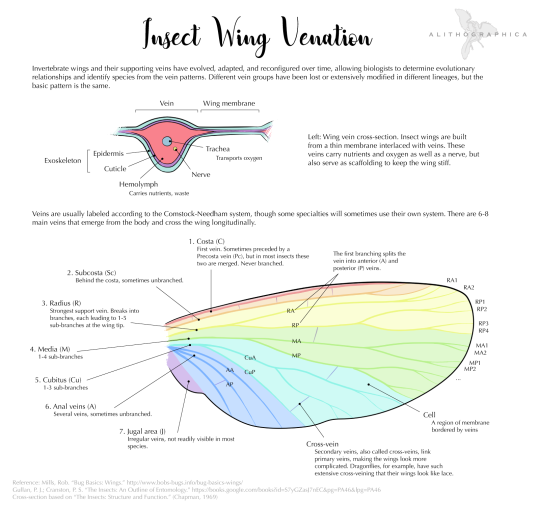

I was last week years old when I learned that insect wing veins have specific labels and can be used to trace evolutionary relationships. It had just…not really crossed my mind before.

Anyway enjoy your slightly enhanced character design toolkit.

Transcript below the cut.

Keep reading

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Indigenous languages of the Arctic Circle

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

English is weird

John McWhorter, The Week, December 20, 2015

English speakers know that their language is odd. So do nonspeakers saddled with learning it. The oddity that we all perceive most readily is its spelling, which is indeed a nightmare. In countries where English isn’t spoken, there is no such thing as a spelling bee. For a normal language, spelling at least pretends a basic correspondence to the way people pronounce the words. But English is not normal.

Even in its spoken form, English is weird. It’s weird in ways that are easy to miss, especially since Anglophones in the United States and Britain are not exactly rabid to learn other languages. Our monolingual tendency leaves us like the proverbial fish not knowing that it is wet. Our language feels “normal” only until you get a sense of what normal really is.

There is no other language, for example, that is close enough to English that we can get about half of what people are saying without training and the rest with only modest effort. German and Dutch are like that, as are Spanish and Portuguese, or Thai and Lao. The closest an Anglophone can get is with the obscure Northern European language called Frisian. If you know that tsiis is cheese and Frysk is Frisian, then it isn’t hard to figure out what this means: Brea, bûter, en griene tsiis is goed Ingelsk en goed Frysk. But that sentence is a cooked one, and overall, we tend to find Frisian more like German, which it is.

We think it’s a nuisance that so many European languages assign gender to nouns for no reason, with French having female moons and male boats and such. But actually, it’s we who are odd: Almost all European languages belong to one family–Indo-European–and of all of them, English is the only one that doesn’t assign genders.

More weirdness? OK. There is exactly one language on Earth whose present tense requires a special ending only in the third-person singular. I’m writing in it. I talk, you talk, he/she talks–why? The present-tense verbs of a normal language have either no endings or a bunch of different ones (Spanish: hablo, hablas, habla). And try naming another language where you have to slip do into sentences to negate or question something. Do you find that difficult?

Why is our language so eccentric? Just what is this thing we’re speaking, and what happened to make it this way?

English started out as, essentially, a kind of German. Old English is so unlike the modern version that it’s a stretch to think of them as the same language. Hwæt, we gardena in geardagum þeodcyninga þrym gefrunon–does that really mean “So, we Spear-Danes have heard of the tribe-kings’ glory in days of yore”? Icelanders can still read similar stories written in the Old Norse ancestor of their language 1,000 years ago, and yet, to the untrained English-speaker’s eye, Beowulf might as well be in Turkish.

The first thing that got us from there to here was the fact that when the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes (and also Frisians) brought Germanic speech to England, the island was already inhabited by people who spoke Celtic languages–today represented by Welsh and Irish, and Breton across the Channel in France. The Celts were subjugated but survived, and since there were only about 250,000 Germanic invaders, very quickly most of the people speaking Old English were Celts.

Crucially, their own Celtic was quite unlike English. For one thing, the verb came first (came first the verb). Also, they had an odd construction with the verb do: They used it to form a question, to make a sentence negative, and even just as a kind of seasoning before any verb. Do you walk? I do not walk. I do walk. That looks familiar now because the Celts started doing it in their rendition of English. But before that, such sentences would have seemed bizarre to an English speaker–as they would today in just about any language other than our own and the surviving Celtic ones.

At this date there is no documented language on Earth beyond Celtic and English that uses do in just this way. Thus English’s weirdness began with its transformation in the mouths of people more at home with vastly different tongues. We’re still talking like them, and in ways we’d never think of. When saying “eeny, meeny, miny, moe,” have you ever felt like you were kind of counting? Well, you are–in Celtic numbers, chewed up over time but recognizably descended from the ones rural Britishers used when counting animals and playing games. “Hickory, dickory, dock”–what in the world do those words mean? Well, here’s a clue: hovera, dovera, dick were eight, nine, and ten in that same Celtic counting list.

The second thing that happened was that yet more Germanic-speakers came across the sea meaning business. This wave began in the 9th century, and this time the invaders were speaking another Germanic offshoot, Old Norse. But they didn’t impose their language. Instead, they married local women and switched to English. However, they were adults and, as a rule, adults don’t pick up new languages easily, especially not in oral societies. There was no such thing as school, and no media. Learning a new language meant listening hard and trying your best.

As long as the invaders got their meaning across, that was fine. But you can do that with a highly approximate rendition of a language–the legibility of the Frisian sentence you just read proves as much. So the Scandinavians did more or less what we would expect: They spoke bad Old English. Their kids heard as much of that as they did real Old English. Life went on, and pretty soon their bad Old English was real English, and here we are today: The Norse made English easier.

I should make a qualification here. In linguistics circles it’s risky to call one language easier than another one. But some languages plainly jangle with more bells and whistles than others. If someone were told he had a year to get as good at either Russian or Hebrew as possible, and would lose a fingernail for every mistake he made during a three-minute test of his competence, only the masochist would choose Russian–unless he already happened to speak a language related to it. In that sense, English is “easier” than other Germanic languages, and it’s because of those Vikings.

Old English had the crazy genders we would expect of a good European language–but the Scandinavians didn’t bother with those, and so now we have none. What’s more, the Vikings mastered only that one shred of a once lovely conjugation system: Hence the lonely third-person singular -s, hanging on like a dead bug on a windshield. Here and in other ways, they smoothed out the hard stuff.

They also left their mark on English grammar. Blissfully, it is becoming rare to be taught that it is wrong to say Which town do you come from?–ending with the preposition instead of laboriously squeezing it before the wh-word to make From which town do you come? In English, sentences with “dangling prepositions” are perfectly natural and clear and harm no one. Yet there is a wet-fish issue with them, too: Normal languages don’t dangle prepositions in this way. Every now and then a language allows it: an indigenous one in Mexico, another in Liberia. But that’s it. Overall, it’s an oddity. Yet, wouldn’t you know, it’s a construction that Old Norse also happened to permit (and that modern Danish retains).

We can display all these bizarre Norse influences in a single sentence. Say That’s the man you walk in with, and it’s odd because (1) the has no specifically masculine form to match man, (2) there’s no ending on walk, and (3) you don’t say in with whom you walk. All that strangeness is because of what Scandinavian Vikings did to good old English back in the day.

Finally, as if all this weren’t enough, English got hit by a fire-hose spray of words from yet more languages. After the Norse came the French. The Normans–descended from the same Vikings, as it happens–conquered England and ruled for several centuries, and before long, English had picked up 10,000 new words. Then, starting in the 16th century, educated Anglophones began to develop English as a vehicle for sophisticated writing, and it became fashionable to cherry-pick words from Latin to lend the language a more elevated tone.

It was thanks to this influx from French and Latin (it’s often hard to tell which was the original source of a given word) that English acquired the likes of crucified, fundamental, definition, and conclusion. These words feel sufficiently English to us today, but when they were new, many persons of letters in the 1500s (and beyond) considered them irritatingly pretentious and intrusive, as indeed they would have found the phrase “irritatingly pretentious and intrusive.” There were even writerly sorts who proposed native English replacements for those lofty Latinates, and it’s hard not to yearn for some of these: In place of crucified, fundamental, definition, and conclusion, how about crossed, groundwrought, saywhat, and endsay?

But language tends not to do what we want it to. The die was cast: English had thousands of new words competing with native English words for the same things. One result was triplets allowing us to express ideas with varying degrees of formality. Help is English, aid is French, assist is Latin. Or, kingly is English, royal is French, regal is Latin–note how one imagines posture improving with each level: Kingly sounds almost mocking, regal is straight-backed like a throne, royal is somewhere in the middle, a worthy but fallible monarch.

Then there are doublets, less dramatic than triplets but fun nevertheless, such as the English/French pairs begin/commence and want/desire. Especially noteworthy here are the culinary transformations: We kill a cow or a pig (English) to yield beef or pork (French). Why? Well, generally in Norman England, English-speaking laborers did the slaughtering for moneyed French speakers at the table. The different ways of referring to meat depended on one’s place in the scheme of things, and those class distinctions have carried down to us in discreet form today.

The multiple influxes of foreign vocabulary partly explain the striking fact that English words can trace to so many different sources–often several within the same sentence. The very idea of etymology being a polyglot smorgasbord, each word a fascinating story of migration and exchange, seems everyday to us. But the roots of a great many languages are much duller. The typical word comes from, well, an earlier version of that same word and there it is. The study of etymology holds little interest for, say, Arabic speakers.

To be fair, mongrel vocabularies are hardly uncommon worldwide, but English’s hybridity is high on the scale compared with most European languages. The previous sentence, for example, is a riot of words from Old English, Old Norse, French, and Latin. Greek is another element: In an alternate universe, we would call photographs “lightwriting.”

Because of this fire-hose spray, we English speakers also have to contend with two different ways of accenting words. Clip on a suffix to the word wonder, and you get wonderful. But–clip an ending to the word modern and the ending pulls the accent along with it: MO-dern, but mo-DERN-ity, not MO-dern-ity. That doesn’t happen with WON-der and WON-der-ful, or CHEER-y and CHEER-i-ly. But it does happen with PER-sonal, person-AL-ity.

What’s the difference? It’s that -ful and -ly are Germanic endings, while -ity came in with French. French and Latin endings pull the accent closer–TEM-pest, tem-PEST-uous–while Germanic ones leave the accent alone. One never notices such a thing, but it’s one way this “simple” language is actually not so.

Thus English is indeed an odd language, and its spelling is only the beginning of it. What English does have on other tongues is that it is deeply peculiar in the structural sense. And it became peculiar because of the slings and arrows–as well as caprices–of outrageous history.

22K notes

·

View notes

Text

german, korean (bengali and russian to an extent)

Langblr Follow Train (January 2020)

Let’s start a langblr follow train to find new langblrs/lingblrs to follow and befriend! 🚂

1. Only langblrs (blogs about languages) and lingblrs (blogs about linguistics), please!

2. Reblog this post before 31.1.2020!

3. Follow some blogs that have reblogged this post!

4. Make new friends!

232 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Intro

Use the hashtag #TheLanguageThread to get your langblr posts (resources, advice, musings) re-blogged into this network!

Start off by re-blogging this post! Follow backs will appear as my primary blog @languagegirl

Knock yourself out!

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

the thesis progress journal

it’s all based on louise desalvo’s concept of a process journal for writers, from her book ‘the art of slow writing’ which i read way back in 2014 but has stayed with me all this time. she based that concept on sue grafton’s journal, which “stands as a record of the conversation she has with herself about the work in progress.” desalvo talks about her own process journal : “to plan a project, list books i want to read, list subjects i want to write about, capture insight about my work in progress, discuss my relationship to my work (what’s working and what’s not, whether i need to make changes to my writing schedule, how i’m feeling about the work)”

her view of the concept is so interesting and can easily be applied to grad school : “keeping a process journal helps us understand that our writing is important work. we value it enough to plan, reflect, and evaluate our work. a process journal is an invaluable record of our work patterns, our feelings about our work, our responses to ourselves as writers, and our strategies for dealing with difficulties and challenges.”

she says, and i quote : “our progress journals are where we engage in the nonjudgmental, reflective witnessing of our work. here, we work at defining ourselves as active, engaged, responsible, patient writers.” and like ???? yes, go off louise!

every week i make an entry with my three to five priorities. since i currently still have seminars, my entire week cannot be dedicated to my thesis, so these priorities allow me to really focus on specific things. they can be bigger or smaller depending on the amount of time i have to work on my thesis.

every day i work on my thesis, i make an entry. i try to answer two questions : “what did i do that day to make progress on my thesis?” as well as “how am i feeling & what i can do to feel better?” i also choose two to five specific tasks to achieve that day and write about the progress. for example, if my task is reading an article, i’ll write it down, check the box once i do it and write a summary of the “experience” (how was the article, was it useful for my research, should i read more of that author’s work, etc.) that way, i can look back at previous tasks, know what happened and learn from it.

i also use the journal almost like a bullet journal (the OG kind) with ongoing lists of important things. of course, there are some to do lists here and there (even though i prefer having my comprehensive task list on todoist), but it’s mostly things like

names of people who have helped me so i can thank them in my thesis

call numbers of books to borrow or archives to consult

research hypotheses

things to look for in the archives i consult

questions to ask my professor/advisor/archivist/etc.

issues that need to be fixed in my thesis

books/articles to read

additional things to research

i also use it as a regular notebooks for all things thesis. one of my seminars this semester is a methodology course, so i take notes in my journal as reference. i also sometimes will write some reading notes if i don’t have my computer on me, such as key quotes or arguments. also, all of my notes from meetings/calls/emails with my advisor are put in the journal, as well as a any pertinent meeting notes (with an archivist, fellow student, my mom, etc.) lastly, sometimes it just becomes a catch all for brainstorm sessions and random thoughts.

for me, this thesis progress journal is the best way to take a step back from the actual work and reflect on what i’m doing, good or bad, and what i can do to make things better, but most importantly, it allows me to understand my progress.

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

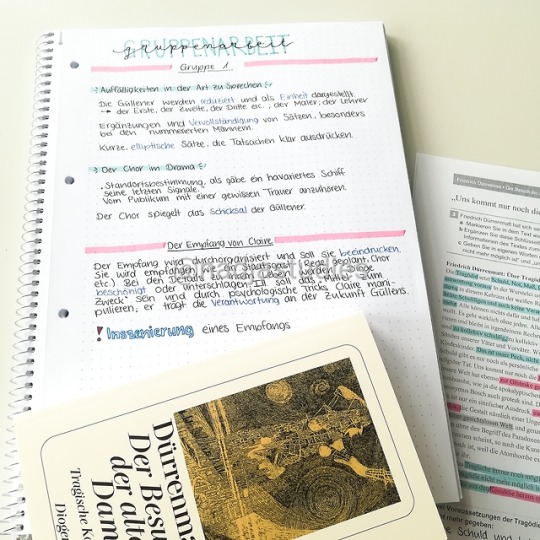

Der Besuch der alten Dame 👵🏼

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

12 new year month-long challenge ideas

don’t buy “extra” stuff for a month 💸 - that means no shopping for clothes, no starbucks, no restaurant dates, no random pretty stationery. buy only what you truly need.

learn a language every day for a month 🌍 - there are tons of apps and recources out there meant to help you learn a new language. don’t give up after a week long streak, make it a month!

read (x) pages every day for a month 📖 - looking at my not-even-half-done goodreads challene makes me sad, so working on reducing my tbr list is one of my top priorities this upcoming year

watch a (short) documentary every day for a month 📽 - make a new folder on youtube and add all educational videos you think you’d find interesting to it. there are countless channels out there - crashcourse, it’s okay to be smart, kurzgesagt, ted-ed (…) with variety of amazing videos

study for (x) hours every day for a month 🧠 - it’s easy not to do anything school related when you have an exam-free week, but when the time comes, you might find yourself overwhelmed with work. try to study every day, but be mindful of your mental health.

meditate every day for a month 🧘 - find a good youtube meditation coach or install an app and use it. even if it’s only three minutes a day, it could make a big difference.

work out every day for a month 🏃 - other than working on your mental health, you need to take care of your physical health as well. a workout can be anything from a simple 5-minute stretch, to a 2-hour long gym session!

reach 10k steps every day for a month 🚶 - a lot of phones have pedometers pre-installed, but if your phone doesn’t, i truly recommend getting a step counting app. go out and get some fresh air! if it’s too cold outside, you can walk around in circles in your house

drink (x) liters of water every day for a month 💧 - pure water might not be everybody’s cup of tea (hah), but an actual cup of tea might be! if you don’t like drinking plain water, make sure to get enough of it via tea, coffee, soups…

eat vegeterian/vegan every day for a month 🥗 - if you decide to do this, make sure to get informed beforehand and see if this could cause you any health problems. if it’s safe for you, prepare to be met with a lot of advantages of this lifestyle!

no chocolate/added sugar for a month 🍫 - i had a bad habit of over-snacking on sweets, but cutting just chocolate or just added sugar led me to far healthier eating habits! you don’t have to give up both at the same time!

go to sleep early & wake up early every day for a month ⏰ - or at least get no more and no less than eight hours of sleep every night! but, for example, going to sleep at 10pm and waking up at 6am is what this challenge is aiming for.

5K notes

·

View notes