Link

Hey! I’m moving this project, and all my writing, over to an external blog. Check it out!!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 13: Wheelbarrow

Today we’ve got another nice little chunk of narrative, after those low-key backstory and religious chapters. But, it also finds plenty of time for fun little asides and bits of philosophy here and there, so it ends up being quite long.

I’m trying to get out of the mode of going through the whole chapter point by point. There’s just too much in this book, and its very existence warns against that kind of close analysis as a sisyphean task. So, I will try to restrict myself to the points and observations I find most interesting.

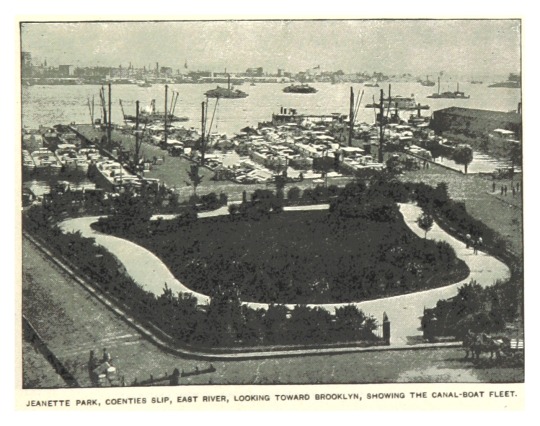

SUMMARY: Ishmael and Queequeg have breakfast at the Spouter-Inn and then set off with all their luggage in a borrowed wheelbarrow to find the ferry over to Nantucket. They ramble through town and chat some more, exchanging anecdotes as they go. They board the ferry, a schooner called “the Moss”, and are revived by the sight and smell of the sea. On the trip to Nantucket, Queequeg is mocked by a couple of green country bumpkins, causing him to throw one into the air, flip him around, and land him on his feet. The bumpkin complains to the captain, who warns Queequeg against further mischief. That very same bumpkin falls in the water when a boom flies loose, and Queequeg then not only secures the boom but rescues the bumpkin, saving his life.

As I said, quite a bit going on here. Let’s hit some notable points.

There is a running theme in this chapter of people reacting to the close friendship of Ishmael and Queequeg, an ordinary New Yorker and a cannibal from the other side of the world. Even the other whalers in the Spouter-Inn mock them, and they really ought to be worldly enough to accept such things. They get stares on the streets of New Bedford, and then endure mockery at the hands of bumpkins aboard “the Moss”.

You can see a couple of interesting things here. One is that while we’ve been assured that the presence of strange folks from all over the world is considered No Big Deal in the whale fishery or on the streets of noted whaling town New Bedford, the friendship between one of them and a white sailor makes everyone look twice. It’s okay for “savages” to be around as long as they act and are treated properly, as outsiders. It is necessary to have them around, but they are not to be brought in and integrated into the social fabric. They must keep their own counsel, any actual mixing between races, even in friendship, is shocking and forbidden.

You can see where I’m going with this, it’s the old colonial/slave trade fear of miscegenation. It’s always struck me as very strange, something really “of the past”, but there are people still living who are violently opposed to it. It’s an ancient idea, really, the whole separation of in-groups and out-groups and whatnot, but the way it was applied to the scheme of racism in the colonial Americas is really particularly vile.

Ah, but I shouldn’t get too far off track. The purpose of these passages in this particular chapter is a little different. This mockery is there so that Queequeg can respond to it, and thus again prove his superiority.

You see, Queequeg doesn’t really care. He is above such petty concerns as what other people think of him. He is stoic in the face of this mockery, and takes a longer and wider view. After relating a story of not knowing how to use a wheelbarrow when he first arrived in America, he tells a story about some visiting traders in his own homeland were ignorant of dining customs. Everyone has something they can laugh at other people about. No need to get all riled up about it, it’s all in good fun.

Which is not to say that he will allow himself to be mocked, as we see on “the Moss” when he tosses that bumpkin into the air, but again it’s just teasing back and forth. The general rule, again, is to just take things in stride. Queequeg knows that he can rely on his physical power to make up for any social shortcomings. He walks around town with a razor sharp harpoon in his hand, those New Bedford townies can say whatever they like behind his back but they’re not going to disrespect him to his face.

Ishmael follows his lead, but instead of an inner confidence he’s simply too distracted by internal philosophizing and the joy of his new friendship to really care. When they arrive at the docks, both Ishmael and Queequeg are revived:

Gaining the more open water, the bracing breeze waxed fresh; the little Moss tossed the quick foam from her bows, as a young colt his snortings. How I snuffed that Tartar air!—how I spurned that turnpike earth!—that common highway all over dented with the marks of slavish heels and hoofs; and turned me to admire the magnanimity of the sea which will permit no records.

And we see here again that disdain for the land and love of the sea. The land is common and pedestrian, set in its ways, but the sea is mysterious and ever-changing. It allows escape from the boring everyday life, and even toil upon it is more exciting and inspiring. Remember that this book began with a description of the way that all humanity is drawn to water.

Anyway, this chapter also has one of my favorite bits of prose:

But there were some boobies and bumpkins there, who, by their intense greenness, must have come from the heart and centre of all verdure.

Ishmael really has no patience for country bumpkins whatsoever. It is his one prejudice.

Ah, another long chapter down. Next time, we’ll finally get to Nantucket! And hoo boy does Ishmael have some things to say about that venerable speck of an island.

Until next time, shipmates!

Image credits:

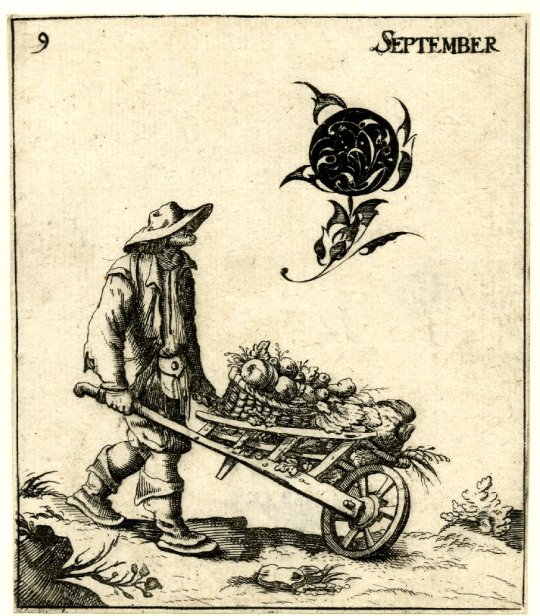

A beggar carrying his wife in a wheelbarrow (1470-1490), by B x G

September (1638), by Paulus Furst

#Moby-Dick; or The Whale#moby dick#herman melville#ishmael#queequeg#new bedford#nantucket#schooner#wheelbarrow#bumpkins

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 12: Biographical

With this chapter, we briefly move back into one of Melville’s more comfortable, more popular subjects: The south seas, which is to say the islands of the southern Pacific ocean.

As I mentioned before, this chapter isn’t an exact transcript of what Queequeg told Ishmael that night, but rather a sort of reconstructed narrative based on that, information later gleaned from Queequeg, and from other miscellaneous individuals who knew of the story.

SUMMARY: Queequeg was born on the island of Rokovoko, somewhere far to the southwest. He was the son of the island’s king, and nephew of its high priest, and grew up in the lap of luxury. But he wanted to go and learn from Christians about the wider world, so he tried to ship off on a whaling ship that landed there, but they refused to take him. So, Queequeg paddled out to the ship as it was sailing away, leapt up on the deck, and grabbed hold of a ring-bolt. He said that the only way to remove him would be either to welcome him as a crewman, or cut him to pieces then and there, so the captain relented and agreed to take him. Thus, Queequeg became a harpooneer. After hearing this story and asking a few questions, Ishmael finally lays back and falls asleep with his new friend.

I wasn’t quite sure how detailed to get with the summary, but it makes more sense to leave a few interesting tidbits for the full analysis. Don’t want the summary to get too long, it defeats the purpose.

So, there are a number of interesting things going on here. Let’s start with what this chapter is actually relaying, what sort of form it’s taking. This is a chapter in a book written by Future-Ishmael, relating the time that he heard the life story of his dear friend Queequeg, but also embellishing it with additional clarity and details gleaned at a later time. But with the interjected questions towards the end, and the bit with Past-Ishmael and Queequeg falling asleep, it’s still relating an event as it happened rather than being a fully cleaned up narrative.

We don’t find out exactly what details were revealed when, by who, because it doesn’t really matter. This is the relevant bits, the Story of Queequeg as Ismael has come to understand it. In this, we get some more foreshadowing of the fate of Queequeg, since there is no further story to tell.

Something that I found interesting in this chapter is how Ishmael casually refers to Queequeg as a cannibal as if that isn’t some shocking truth, but a simple statement of fact. He never really casts judgment on the practice, it’s just the way things are done in the place that he’s from. There are a couple ways to read this:

- The judgment that “cannibalism is wrong” doesn’t really need to be made, it’s taken for granted. Merely by calling him a cannibal, Ishmael is drawing upon a wealth of cultural understand with regards to the dichotomy between the “savages” and the “civilized”.

- Who is Ishmael to judge his fellow man for their cultural practices? Are the wars that are fought between supposedly “civilized” nations really any better because we don’t eat the dead? It’s all relative, man, no need to get hung up on the details.

- Ishmael is trying to project a kind of worldliness that isn’t shocked or appalled by cannibalism, despite any feelings he may truly be harboring about it. He’s an experienced whaler, and he’s known tons of cannibals and it’s not even a big deal. Basically, being a bit of a show-off through nonchalance.

I think it’s some combination of all of them, really. Ishmael would obviously be appalled by cannibalism as a practice, but in the context of it being a thing his dear friend has done in the past, he’s not gonna let it get in the way. And he is highlighting in order to give a bit of that ol’ Gritty Realism for this book he’s writing.

This is also probably what Melville is doing. I mentioned before that this is his wheelhouse, and that’s because his earlier, much more successful novels were south-seas adventures, called Typee and Omoo. They were massively popular, and much more traditional is form. I’ve never read them.

It’s also just being used as shorthand for the fact that Queequeg is from a small south pacific island where the people were “savages”, of course. But many of the assumptions about his people are challenged in this and the next chapter. They’re not weird monsters just champing at the bit to eat more civilized folks, they’re just people. The expectations of some wild origin for Queequeg are effectively undermined.

Similarly, Queequeg has his own expectations undermined when he finally gets back to the great Christian civilization he’s heard so much about. He doesn’t get into details, but when he saw how his fellow sailors acted when they got back to America, he decided that maybe Christians aren’t so great after all. This was supposed to be a great journey to acquire useful knowledge and philosophy from a faraway land, but it turns out he just ended up in another place like any other, or worse even than his relatively pure and peaceful island home.

Thus, Queequeg isn’t really on any grand quest, he’s just kinda going along, plying his trade. This would probably explain why he is so happy to have a friend in Ishmael, to finally have some close companionship that isn’t driven away by his outlandish appearance and origin.

Indeed, Queequeg decides right then and there that he’ll not only go to Nantucket with Ishmael, but he’ll go on the same ship and try to share the same watch with him. He is already deeply committed, ready to “share his every hap”.

The other question that Ishmael asks is if Queequeg would ever go back to Rokovoko and become king? His father must be dead by now, and his birthright is waiting for him. But Queequeg demurs, he’s spent too much time around Christians and fears that their bad influence has corrupted him. The pure pagan-ness of the throne of Rokovoko must be protected, after all.

It’s another interesting inversion of expected moral judgments. It doesn’t even feel to me like the old Noble Savage stereotype, the Rokovokans aren’t portrayed as being especially moral or superior. They’ve just got their own way of life, and Christians haven’t proven to be any better, certainly, so they have a right to want to keep things the way they are.

One theme that is established here is the idea of Royalty as a sort of attitude towards the world, a material way of being. Ishmael compares Queequeg to Czar Peter the Great of Russia, who worked anonymously in foreign shipyards as a youth. Queequeg doesn’t care what kind of work he is asked to do or what sorts of ignominy or toil he must endure to accomplish his goals. As a true king, or at least prince, his concerns are higher than such things as his own health and safety.

Ishmael (and Melville) exhibit a classic American infatuation with the concept of royalty, while at the same time rebelling against it as a natural law. Certain people act like royalty, but nature is fundamentally democratic and meritocratic. It is their actions that make them royal, not their ancestry. This will come up again a lot, later on.

Whew, another big important chapter down. Still establishing some themes, we’ll follow up with a lot of this stuff in the near and distant future. Come to think of it, we get a lot more information about Queequeg’s backstory than we ever do about Ishmael himself. I’ll have to keep an eye out for scraps of information in that vein as we continue.

Next up is a rather eventful, fully narrative chapter, about the pair’s journey to Nantucket. Then they’ll actually be able to start looking for a whaling ship to sign onto!

Until next time, shipmates!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 11: Nightgown

So, now that our old pal Ishmael has gotten himself hitched, let us follow him into his marital bedchamber for a bit of intimate action. This is another short one, but contains one of my absolute favorite passages in the whole book!

SUMMARY: Ishmael and Queequeg go to bed. They stay up late chatting with each other about various things, shifting around in various positions. Eventually, they both realize they are no longer sleepy at all, and sit up in bed. Queequeg lights a lamp and starts smoking, sharing again with Ishmael. Ishmael asks Queequeg about his homeland, so he tells the story of how he came to be a harpooneer in the American whale fishery.

So, not exactly the kind of “intimate action” you may have been expecting. But hey, Moby Dick is known as a musty old Important Book, and even though I think it’s a lot funnier and easier to read than its reputation would indicate, that doesn’t mean it’s gonna have a secret gay sex chapter. At least, not yet.

Although, in the opening paragraph Ishmael does describe “Queequeg now and then affectionately throwing his brown tattooed legs over mine, and then drawing them back,” so it’s a bit open to interpretation. Nonetheless, the main action of this chapter is two good, good friends sharing a bed together, talking, and being extremely comfy. It’s good stuff.

Indeed, the main thrust of this chapter is a bit of a treatise on the nature of comfiness, and how best to achieve optimal comfort in even the most adverse circumstances. If you’ll recall, before Ishmael met Queequeg, when he first arrived at the Spouter-Inn, he had a hell of a time trying to find suitable sleeping arrangements. He tried putting two benches together, but it just didn’t work. He fretted about sleeping in another bed with someone else, and even when he got in the bed, he lamented that the mattress was stuffed with corn cobs and broken crockery.

And yet now, he is the most comfortable man in the whole wet world, in that very same bed. Ishmael puts forth his theory on comfort and snugness thusly:

We felt very nice and snug, the more so since it was so chilly out of doors; indeed out of bed-clothes too, seeing that there was no fire in the room. The more so, I say, because truly to enjoy bodily warmth, some small part of you must be cold, for there is no quality in this world that is not what it is merely by contrast. Nothing exists in itself. If you flatter yourself that you are all over comfortable, and have been so a long time, then you cannot be said to be comfortable any more. But if, like Queequeg and me in the bed, the tip of your nose or the crown of your head be slightly chilled, why then, indeed, in the general consciousness you feel most delightfully and unmistakably warm. For this reason a sleeping apartment should never be furnished with a fire, which is one of the luxurious discomforts of the rich. For the height of this sort of deliciousness is to have nothing but the blanket between you and your snugness and the cold of the outer air. Then there you lie like the one warm spark in the heart of an arctic crystal.

And I must say that I agree wholeheartedly with every single letter of that. Is it not a wonderful feeling to know that there is cold all around you, bitter and terrible cold, but to be nice and warm? Just as there is nothing better than sitting inside in a coffee shop or a living room with a view of a raging rainstorm outside. The contrast of your position with the knowledge of the extremity of the external elements enhances the feeling of safety and comfort.

This is why colder, or at least more temperate, regions are better for human habitation. It is the only place where this experience is really possible to attain.

But this quirk of comfort may have darker implications as well. If we can extend this love of contrast to other areas of human experience, it may be the cause, or at least perpetuator, of a great many evils in the world. Consider: is winning really worth if nobody is losing? If there are no natural losers, might you be tempted to punish some so that you may feel like you are winning more?

It drives the great class struggles of our time, I would posit. Everyone wants to be above someone. It is one of the factors in the perpetuation of slavery, in days gone by and today. Even the lowest man wants to feel like he is above somebody, and that drives racial hatred. Instead of helping each other and working towards a better future, we become obsessed with who is winning and who is losing, and how to be in the former category rather than the latter.

I wish that everyone could see that life is not only not a zero-sum game, but is not a game at all. There are no winners and losers, there are simply people trying to get by. Nobody is going to give you a score at the end of it all, there are no rankings or leaderboards. Every human has dignity, whether you treat them that way or not.

Anyway, back in the book, in Ishmael and Queequeg’s intimate night-time chat, we touch on another big theme for the book. While he was laying down, and even when he first sat up in bed, Ishmael kept his eyes firmly closed, believing that it is the only way for a man to “feel his identity aright”. He goes on to hypothesize that perhaps the natural state of man is to be in darkness.

This sort of flip-flopping of the traditional roles of light and darkness, one as evil and unnatural and the other as good and pure, is one of the big ongoing themes in this book. Here, we get the idea that perhaps being in darkness is a position of intimate comfort. The cozy snugness of being surrounded on all sides by gloom, the warm darkness of the womb. Not the fearful unknown, but the silent, comforting blackness of closing your eyes in order to get some rest.

Finally, we end the chapter on a nice little metatextual note. The following chapter will recount Queequeg’s origin story, but is not a note-for-note retelling of what Ishmael heard that very night, in that bed. Instead, this is what an older Ishmael managed to put together through many such conversations, and interrogations of other people who also knew his new husband. So, we get a more or less complete version, edited for clarity.

Whew, didn’t think I would end up delving quite so deeply into philosophy just from a fun little pillow talk chapter. But hey, that’s how these things go, sometimes. You never know when inspiration is going to strike, from the littlest things.

Next time, we get into Melville’s old wheelhouse: south seas adventures!

Until then, shipmates!

Image Credits:

Crystal Cave (2011), by Arctic Photo.

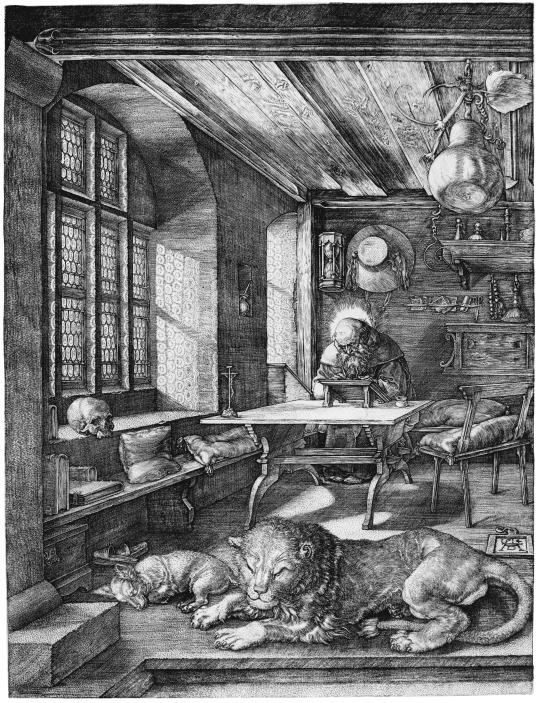

Saint Jerome in His Study (1514), by Albrecht Durer.

The Nightmare (1781), by Henry Fuseli.

#Moby-Dick; or The Whale#moby dick#herman melville#ishmael#queeqeug#philosophy#comfort#coziness#albrecht durer#henry fuseli

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 10: A Bosom Friend

Now that we’ve got church out of the way, it’s time to get real chummy with some dudes just bein’ bros. Just a real couple o’ old pals, pallin’ around! That’s it and that’s all, certainly no subtext here, no sirree.

These next few chapters make an interesting counterpoint to the harsh, literally sermonizing tone of the last little run. It’s a nice change of pace.

SUMMARY: Ishmael gets back to the Spouter-Inn, and finds Queequeg examining a book at the dining room table, counting its pages in awe. Ishmael decides to become friends with Queequeg, and strikes up a conversation. Queequeg is very receptive, and quickly declares them married, and after a while they go on up to their room. Queequeg divides his money evenly, giving half to Ishmael, they then get in bed together and share their deepest secrets with one another, as married couples are wont to do.

So, I mentioned before, back in The Counterpane, that there are a few parts in Moby-Dick; or, the Whale that could be construed, by modern readers, as a bit homoerotic. Queequeg sleeping with his arm around Ishmael, sure, that’s a little gay, but this chapter, hoo boy, there’s really no other way to read it than a budding romance.

I mean, let’s take it point by point. First, Ishmael finds himself merely interested in this strange “savage” who he was forced to sleep with the night before. But as he gazes at him, he takes note of his handsomeness, the fine shape of his head. He delves into phrenology and says that “Queequeg was George Washington cannibalistically developed.“

Phrenology is a pseudoscientific theory from the 19th century that posited that the shape of the head indicated the shape of the brain, which, naturally, determined your personality. You could use some calipers to measure the lumps on a skull and tell if someone was a criminal, by the size of their Crime Organ. It’s pretty interesting, and all obvious hogwash, perfect material for the Sawbones podcast, one of my favorites, who have of course done an episode on it.

Let’s not beat around the bush, Ishmael is secretly checking out Queequeg while pretending to watch the storm outside, “Whilst I was thus closely scanning him, half-pretending meanwhile to be looking out at the storm from the casement.” He is enamored with the stoic personality of his bedfellow, the way he goes through life perfectly self-aware and ease with his own existence, warts and all. Even so very far from his homeland, among these people who must seem so strange to him, Queequeg never falters!

Also this passage, which I take as a personal attack on myself:

Surely this was a touch of fine philosophy; though no doubt he had never heard there was such a thing as that. But, perhaps, to be true philosophers, we mortals should not be conscious of so living or so striving. So soon as I hear that such or such a man gives himself out for a philosopher, I conclude that, like the dyspeptic old woman, he must have “broken his digester.”

And then, and he continues to stare longingly, we get this line

I began to be sensible of strange feelings. I felt a melting in me. No more my splintered heart and maddened hand were turned against the wolfish world.

Ishmael is just falling head over heels in love with Queequeg. He’s got a crush. There is simply no other way to read it, I’m sorry. Ishmael throws away all doubts relating to Queequeg’s origins, decides that since he hasn’t found any true kindness among his fellow christians, he’ll try being friends with a pagan.

There have been some hints and indications of it, but Ishmael is remarkably open-minded and tolerant for a man in the early 19th century. Indeed, after he finally works up the courage to start chatting with Queequeg and they share a smoke, get hitched, and go back to their room, Ishmael has no problem literally worshiping an idol with his best pal.

I really love the logic he uses for it:

I was a good Christian; born and bred in the bosom of the infallible Presbyterian Church. How then could I unite with this wild idolator in worshipping his piece of wood? But what is worship? thought I. Do you suppose now, Ishmael, that the magnanimous God of heaven and earth—pagans and all included—can possibly be jealous of an insignificant bit of black wood? Impossible! But what is worship?—to do the will of God—that is worship. And what is the will of God?—to do to my fellow man what I would have my fellow man to do to me—that is the will of God. Now, Queequeg is my fellow man. And what do I wish that this Queequeg would do to me? Why, unite with me in my particular Presbyterian form of worship. Consequently, I must then unite with him in his; ergo, I must turn idolator.

It’s hard to argue, frankly. A lot of the logic of religion is rooted in more ancient practices that are based in more polytheistic understandings of the world. You’re only supposed to worship your god because you’re on their team, essentially. But if you really believe that your god is the only real one, and all powerful, and all knowing, then why should they be so jealous of your worship? Would they really be so petty as to punish you for being kind to a friend?

Now, as the new married couple settle in to bed for the next chapter, I will entertain some argument about their status as clear and obvious homosexual lovers. There’s nothing explicit here, of course, and I hear you saying that friendship was different in those days.

Long, long ago, before modern society, there was a strange place called The Past, and they have strange habits and customs that look odd to our modern eyes. We may see some men hugging each other, being physically intimate, and think “goodness, how homoerotic!” But, in that time, it was simply more acceptable for men to express physical affection for one another with no sexual subtext whatsoever. They were, in fact, just dudes bein’ bros. Or companions being bosom chums, whatever the 19th century equivalent phrase is.

So what I am reading as something more than friendship was actually just that, and would have been understood to be that at the time.

But I say to you: Yes, things were different in the past, but that cuts both ways! You simply could not speak openly about these things, which were especially common among sailors. There is a famous saying, that the traditions of the Royal Navy amount to “rum, buggery, and the lash” (or something like that). Men cooped up together on a ship for months and months, it’s no surprise, frankly. And there’s no way that Melville, who was a sailor for his entire youth (even if he only went on one whaling voyage) would be naive to these facts.

The language employed in this chapter, I posit, frames this more as a crush and budding romance than anything else. If Melville intended a mere close friendship, he could have written it differently, and who cares what he intended anyway, he’s not around to argue. Interpretation is creative! I say: they’re gay, and make a good couple.

Ah, if this were a serious bit of writing, I would go track down some more sources to cite and whatnot, really develop a strong argument. But hey, I’m just havin’ fun here, not doin’ this for a grade. So you’ll just have to take my word for it.

Up next, The Nightgown, in which we get an intimate portrait of the young lovers in bed, and one of the most #relatable bits in the whole book!

Until next time, shipmates!

Image Credits:

First four from this article, last two from this one. All anonymous photos.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

We’re back and we brought a fish and a pumpkin

PS happy birthday trees

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 9: The Sermon

And here we are, at the climax of the most overtly religious section of Moby-Dick; or, the Whale. Now that the church itself, the pulpit, and Father Mapple have all been introduced, it’s time for the main event!

SUMMARY: Father Mapple gives a sermon on the Book of Jonah.

This chapter starts off with a little taste of the way that Mapple is going to mix in colloquial salty, sailor-ish phrases into his serious religious teachings. He calls everyone from starboard and larboard to come midships, or to gather in the middle of the church, closer to the pulpit.

“Larboard?” you may be wondering, “I thought it was port and starboard”. You would be right, even at the time this book was written, but only just. It was starboard and larboard until the 1840s, when naval captains in Britain got tired of people mishearing and going to the wrong side of the ship. They changed larboard to port, to cut down on that confusion, and the American navy followed suit a few years later. This change was probably just filtering down to merchant ships around the time Melville was writing this book, so it’s hard to blame him.

And, anyway, this book is actually set in the past, having been written by a modern, older Ishmael, so it’s not a mistake even within the fiction!

Fun fact: “Port” isn’t actually much of a change in meaning from “larboard”. It comes from Old English meaning “load board”, or the side of the boat that you load things onto, from the port. “Starboard” comes from “steer board”, or the side you steer from, using an oar, before rudders were invented.

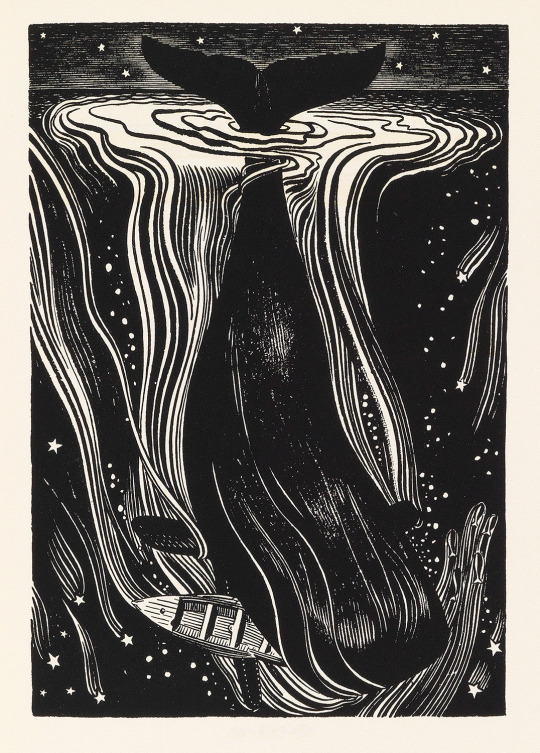

Let’s get into this sermon! It concerns, as you could probably guess, the story of Jonah, from the relatively short Book of Jonah, of the Old Testament of the Bible. The gist of it is that Jonah is ordered by God to go tell the city of Nineveh that they’re acting terribly and God is going to destroy them, but Jonah refuses because he is afraid of what the Ninevites will do it him.

Instead, he tries to run away. This part is wonderfully embellished by Mapple, who really brings life to the sailors and captain of the ship who Jonah books passage with. He emphasizes how guilty Jonah looks, but how he tries to act as though nothing is wrong. There’s a fun bit where the captain suspects him, and so charges him triple the usual rate, and has his suspicions confirmed when Jonah doesn’t even try to haggle. But hey, money is money, so off they go.

You know how this part goes, I’m sure. A storm appears, and will not relent. The sailors cast lots for who to throw overboard to appease the storm, and Jonah gets it. He confesses then and there that he is defying God. Interestingly, the sailors don’t throw him over immediately, but still try to make it through the storm, only finally tossing him as they are on the brink of destruction. Then, the storm goes away, instantly, and Jonah gets eaten by a whale.

In the original text, it actually only says “big fish”, but that came to mean the same thing as whale in Latin, so it’s a whale. We’ll get into some Discourse on whales w/r/t their status as fish or now at a later point.

Jonah finally asks for forgiveness from God, and is spat up on a beach, and goes off to prophesize against the Ninevites.

Mapple draws two lessons from this:

First: If you sin, you have to repent. You have to apologize, and ask for forgiveness, even knowing that some horrible fate may await you. This is one of the sins that Jonah commits, he defies God and then, on the ship in the storm, refuses to repent. That is why he’s swallowed up and taken to the depths of the ocean, until he does finally admit his wrongdoing. And then, even from those same abyssal depths, God hears his plea, and has mercy upon him.

Secondly: It is important to speak truth to falsehood, especially for those who know the truth. Mapple applies this lesson to himself, rather than the congregation. Jonah was told that he was to go tell the Ninevites that they were doing evil, and would be destroyed. But he feared their reaction, and so hid himself away. He was told the truth directly by God, but couldn’t bring himself to tell others. So, it is a great sin to hide your knowledge of the truth, especially as it pertains to God and sin.

Of course, this latter lesson is built on the notion that you know what the truth is, and a major theme of this book is that that’s kind of a questionable business. Ishmael is constantly doubting that anyone can ever know the truth about anything. So this seems like a bit of a moot point, but it applies more to Ishmael’s philosophical opposite, who we have not yet met.

The sermon ends with some bog standard stuff leading off of that, about speaking truth the power and how your reward will be eternal for following the will of God, and so on. Then Mapple simply kneels down in prayer, in the high, lonely fortress of a pulpit remember, and waits there silently until everyone has left.

Something that’s hard to get across with this chapter, and you may not notice even if you read it, is that it is definitely written to be an actual oratory, a speech that you give out loud. It simply flows better if spoken aloud, preferably in a loud voice, perhaps standing or sitting in a huge armchair next to a great roaring fire. Take this passage, and notice the rhythm of it, the ebb and flow, and try saying it aloud to yourself:

Miserable man! Oh! most contemptible and worthy of all scorn; with slouched hat and guilty eye, skulking from his God; prowling among the shipping like a vile burglar hastening to cross the seas. So disordered, self-condemning is his look, that had there been policemen in those days, Jonah, on the mere suspicion of something wrong, had been arrested ere he touched a deck. How plainly he’s a fugitive! no baggage, not a hat-box, valise, or carpet-bag,—no friends accompany him to the wharf with their adieux. At last, after much dodging search, he finds the Tarshish ship receiving the last items of her cargo; and as he steps on board to see its Captain in the cabin, all the sailors for the moment desist from hoisting in the goods, to mark the stranger’s evil eye.

It’s just great. Honestly, this chapter may be one of the most influential on my own style of writing. I try to simply write how I would speak, most of the time. It works pretty well, keeps the energy up, gives it more of an easy, readable flow.

Oratory was a much more important thing in the 19th century, and before. Many people made their livings going around giving speeches, especially authors. In the ages before mass communication through radio, being able to give a powerful, persuasive speech in person was a very valuable skill. This kind of sermon would be very common, and in fact they were often transcribed and sold later, in printed form.

There are many themes introduced here that will come back many times. The idea of a man struggling to comprehend the will of God is a big one. We see again an idea of disregarding petty physical things in favor of actually important spiritual concerns, although from a very different angle. Mapple says that you’ll have a true, better reward if you do the right thing, and that any physical torment you suffer will be worth it, as opposed to Ishmael thinking that none of this physical stuff even matters at all, as it’s only a small part of his true existence.

This is kind of the introduction, then, of another major theme: Destroying your body in service to another. In this case, it’s in service of God, telling Jonah to go do a thing that might get him hurt, but is scary. We’re going to get some stronger, more direct versions of this once we actually get on a whaling ship.

The style of this chapter is so strikingly different from all the others, it’s definitely one of my favorites. Melville is able to really show off his gift for writing prose here. Try not to skim over it, it’s worth it to take in all that good nautical language.

Ah, that was a fun one. Lots of stuff to talk about there, and I really only scratched the surface. We’re still planting the seeds for a lot of big themes that will only come into full bloom much later in the book.

The next chapter is A Bosom Friend, and is an interesting counterpoint to this one. A bit less on the overt religious themes, and a bit more down to earth and heartwarming.

Until next time, shipmates!

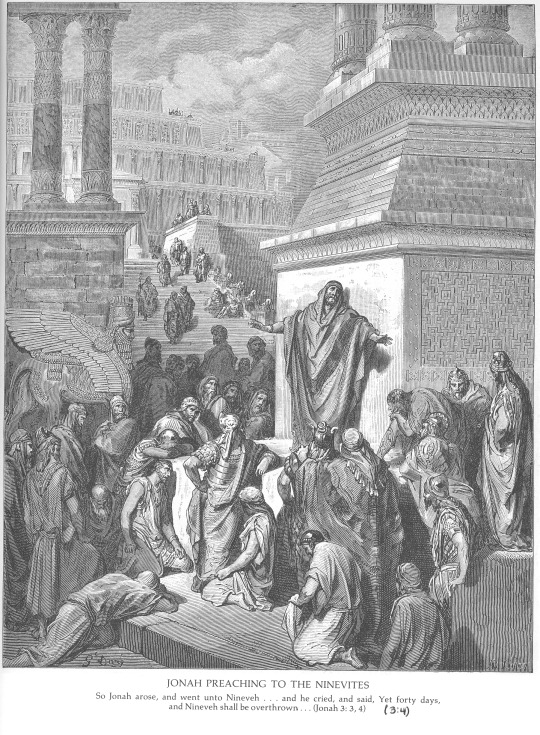

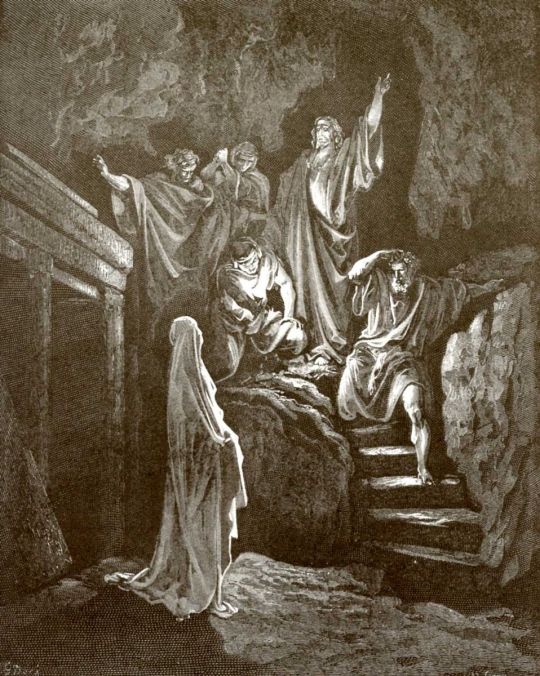

Image credits, in order:

Jonah and the giant fish (1400), Jami al-tawarikh, by Rashid-al-Din Hamadani.

Jonah and the Whale (1621), by Pieter Lastman.

Jonah Cast Forth By the Whale & Jonah Preaching to the Ninevites (1866), by Gustave Dore.

#Moby-Dick; or The Whale#moby dick#herman melville#19th century literature#ishmael#father mapple#jonah#book of jonah#philosophy#theology

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Woops, put this one on the other blog.

Well, here it is!

Chapter 8: The Pulpit

Let us continue the Theology lessons, here in this, the most churchy run of chapters in Moby-Dick; or, the Whale.

This chapter contains some really meat in that particular vein, as well as appealing to a particular style of Christian aesthetic that I enjoy a great deal. After the doubts raised in The Chapel, it’s time to get a little more sincere, as the chaplain finally makes his appearance.

Keep reading

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 7: The Chapel

Let’s move on to some capital-T Theology in this next run of chapters in Moby-Dick; or, the Whale! I’ll say ahead of time that I am, at best, an amateur theologian, having taken only a few classes on the subject in college, and none of them even remotely relating to 19th century Christianity.

But, having been raised in a denomination that encourages scholarship of the Bible, following @benito-cereno for many years on this site, and listening to his wonderful podcast @apocrypals, I know a thing or three about the following of ol’ Oily Josh.

SUMMARY: Ishmael returns to the inn after his morning perambulations, then leaves again to visit the famous Whaleman’s Chapel of New Bedford. The weather has turned bad, sleeting heavily, but he makes it there, crusted over in ice. The chapel is already half full of various worshipers, each sitting apart and silently in their grief, gazing at the memorial tablets on the wally behind the pulpit. Queequeg is there, but because he can’t read he is unaffected by the gravity of the scene.

So, we transition ever so smoothly from Ishmael extolling the merits of the whale fishery, rhapsodizing about how it has made New Bedford a paradise on earth when it was previously a blasted waste, straight into this, a contemplation of the cost of that wealth. Not only the lives lost in gaining it, but the grief of those left behind, the shipmates and relatives who now suffer eternal grief.

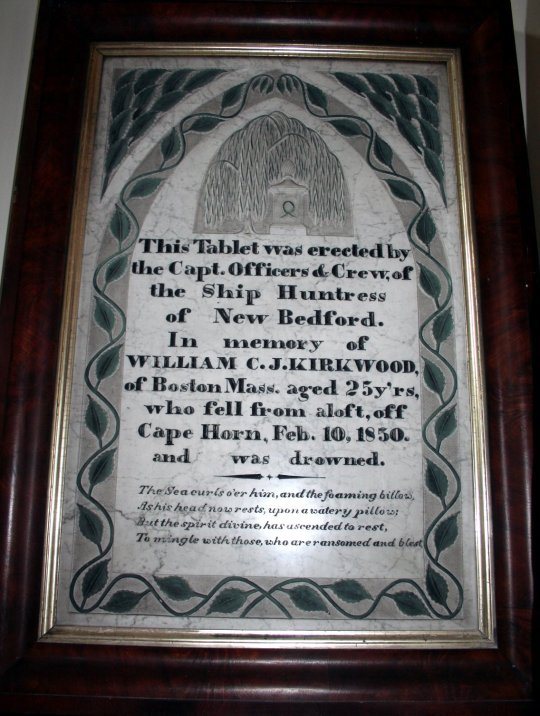

Ishmael explains that the deaths of whalemen in the process of their craft is especially harsh, as their bodies are usually unrecoverable. A boat is simply carried off over the horizon, and everyone on it is accounted as dead. A man is dragged beneath the waves after not cutting a rope soon enough, never to be seen again. He goes overboard during a squall, and only noticed in the morning’s accounting.

Thus, the grief is more keenly felt by those in this particular chapel. Which is a real place, it turns out, but is called the Seaman’s Bethel and not the Whaleman’s Chapel. It is preserved exactly as it is described in this book, and you can go there, in New Bedford, and gaze at those tablets yourself, if you so wish.

Not knowing where your loved one’s body ended up is tragic, because how will you find them when the resurrection comes? Indeed, Ishmael posits that this is the reason the grief is all the deeper and intractable in this place. It undermines the very faith of the grievers, how can they believe in Eternal Life if the bodies of their beloved lay at the bottom of some ocean, thousands of miles away?

This is referring to the concept of Jesus returning to grant eternal life to all who have died. The idea being that when you die, you don’t just go to heaven immediately, but have to stay dead for a while, until Jesus returns to Earth to raise the righteous dead and bring them with him up into paradise. So the placement of bodies after death becomes a very important thing, in Christianity.

There’s a whole Thing about what these resurrected dead will be like, and be able to do, which is buck-fucking-wild, but I’m not gonna get into that here. Check out episode 5 of the aforementioned podcast, Apocrypals, for more info on all that.

Getting back to the text, I really didn’t understand this bit at all the first time I read it, but now it makes more sense, being aware of the whole second-coming-resurrection thing. Ishmael gets more philosophical here, wondering why people care so much about where the bodies lay, or why people care about their loved ones being dead at all! After all, they’ll be back as immortal spirits in no time. They’re not even really dead, just resting until the second coming.

And yet, there is grief. There is sorrow eternal, over the placeless dead. There is fear over the idea of resurrection itself. Ishmael seems to be picking at a contradiction here, that people don’t really believe in these things. Or, that the faith itself only sustains itself by offering hope to those in the depths of despair. You may say, taking advantage of those who are desperate for a shimmer of hope.

But Faith, like a jackal, feeds among the tombs, and even from these dead doubts she gathers her most vital hope.

Then, Ishmael gets really philosophical, right in the last paragraph.

After contemplating the tablets seemingly foretelling his own death in his forthcoming voyage, he decides to take the whole thing in stride. Sure, maybe he’ll die in some ignominious way in some random accident, but so what? He’s just getting it over with, getting a promotion to an immortal spirit, shedding his earthly form early.

Methinks we have hugely mistaken this matter of Life and Death. Methinks that what they call my shadow here on earth is my true substance. Methinks that in looking at things spiritual, we are too much like oysters observing the sun through the water, and thinking that thick water the thinnest of air. Methinks my body is but the lees of my better being. In fact take my body who will, take it I say, it is not me. And therefore three cheers for Nantucket; and come a stove boat and stove body when they will, for stave my soul, Jove himself cannot.

So, what we see as the world is not necessarily the truth of it. Ishmael is going full Descartes here, saying that the only thing you can know for sure is that you exist. The true nature of the world is not revealed to us by appearances.

That is definitely gonna show up a lot in this book, as an ongoing theme. The world that presents itself to our eyes, at a glance, is not even a fraction of the whole story when it comes to whales. Why should it be so for anything else? What appears to be the important things in life, the physical things, are just impermanent shadows, compared to the eternal nature of the soul!

Sounds an awful lot like Gnosticism to me, frankly. Melville was a bit of a heretic! Not that he ever claimed not to be. Gnosticism being the off-shoot of christianity, going way back to the very early days, which posits that the physical world was made by an evil being called the Demiurge and exists only to corrupt the pure, spiritual essence of mankind.

But, really, Melville isn’t being specific enough to be slotted into any particular theology or philosophy. The whole point is that knowledge is impossible. You can try and try, but to really get to the true truth? The real reality? It is completely unknowable whether you’ve ever reached it.

I warned you it was gonna be a big one, for such a short chapter. And this isn’t even getting into all the meaning I could wring out of that line about faith being like a jackal. I’ve basically made that quote the basis for this indie game project I’ve been working on, and even used it as a prospective name!

The deep stuff in this book comes out of nowhere, sometimes. One chapter Ishmael is opining about how pretty the girls of New Bedford are in the spring, and the next he’s saying it’s okay if he dies because this physical world is but an illusion. Go figure!

As always, you can follow along with the full text of the book FOR FREE on Gutenberg dot org. Or, there are many free or very cheap editions available on amazon dot com. And if you really want to get fancy, check out the illustrated edition by one Evan Dahm, the author of the webcomics Rice Boy and Vattu.

Until next time, shipmates!

#moby dick#Moby-Dick; or The Whale#ishmael#new bedford#gustave dore#seaman's bethel#gnosticism#philosophy#theology#resurrection bodies

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 6: The Street

What’s this? Two in one day? Sure, why not. Let’s knock another one down!

This chapter is another short one, I actually fit the notes for it and the last one on the same page. It does have a bit more meat for us to chew on, though, in terms of blog writing. I probably won’t have to go off on a Melville-esque digression of my own to get to a decent length this time.

SUMMARY: Ishmael wanders around town, and Old Ishmael, the writer of the book, reminisces about New Bedford.

That’s it! Nothing really happens in this chapter, in terms of the narrative following the younger version of Ishmael. He just goes out and sees what this town is all about, since he’s never been there before. But then we are treated to some remembrances of the older Ishmael, to whom New Bedford is quite familiar.

In a way, you could call this a little non-narrative diversion in this early section of the book. In my memory, this part, before the voyage commences, is all narrative, but this is more of a reflection on the whaling industry, rather than telling the story.

Melville is actually very skilled when it comes to the narrative portions, he gets across action well and is adept at crafting dialog, so these non-narrative digressions are not from laziness or a lack of ability. It’s hard for me, sitting here in the year of our lord two thousand and nineteen, to determine how much of this is the genuine remembrance of Melville himself, and how much is in character as Ishmael. And, I suppose, it doesn’t really matter, at th’ end o’ th’ day.

Anyway, the actual content of this chapter: some of it is just totally incomprehensible to me. Not because it’s written in an old-timey way, as is often the problem with books of this vintage, but because it’s just a list of locations that I have absolutely no idea where they are. A bunch of places in New York where you can see “exotic” folks of various description... which don’t hold a candle to New Bedford. Where there are people from a bunch of South Pacific islands that are spelled in a way that makes it impossible for me to guess what he’s even talking about. I can figure out “Feegeeans” but “Brighggians”? I don’t even know, man.

The long and short of it is that New York is diverse, but New Beford has a whaling fleet so it has people from ALL over, literally. It goes to this theme of whaling being very international, people seek it out from all over the world, because whalers go all over the world in search of their quarry. Also Ishmael refers to “cannibals” again, which, yikes.

Even farmers from rural America are drawn to the whale fishery, not just those exotic specimens from far off lands. Ishmael really likes making fun of these country bumpkins who wander into town totally unprepared. And I love this paragraph from this chapter, where he does so:

No town-bred dandy will compare with a country-bred one—I mean a downright bumpkin dandy—a fellow that, in the dog-days, will mow his two acres in buckskin gloves for fear of tanning his hands. Now when a country dandy like this takes it into his head to make a distinguished reputation, and joins the great whale-fishery, you should see the comical things he does upon reaching the seaport. In bespeaking his sea-outfit, he orders bell-buttons to his waistcoats; straps to his canvas trowsers. Ah, poor Hay-Seed! how bitterly will burst those straps in the first howling gale, when thou art driven, straps, buttons, and all, down the throat of the tempest.

This is also where we get another theme that runs throughout the whole book, especially in the non-narrative chapters: Whaling as a very important, even noble, industry. That is why it attracts people from all over, even people from rural America, and the town of New Bedford is so rich and fancy, despite being situated on a blasted, awful stretch of New England coastline.

Whaling simply brings in a lot of money, because whale oil is worth a lot, because it burns very cleanly for light. Ishmael will go into probably too much detail about this later on, and other lionizing facts, but for now it is enough to know that New Bedford is a rich town. Despite everything, it is a sort of paradise in the middle of a wasteland, transformed by the bounty they reap from the seas.

That’s about all Ishmael has to say about this town. He clearly doesn’t like it as much as Nantucket, as we’ll see when he reaches that vaunted island with his companion in a few chapters. In terms of whaling towns, it’s new money, so to speak. The up-and-comer, who is stealing all the business from the old, traditional port, the originator of the industry.

But he does admit, it is very pretty in the spring.

Another short little chapter, tryin’ to get to the meat of this book. But we’re already starting to build up some themes that will show up time and again later in this old monster of a tome of a book.

As always, you can follow along on the gute. Until next time, shipmates!

#moby dick#Moby-Dick; or The Whale#herman melville#ishmael#new bedford#the green mountains#dandy#fiji#feegee

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 5: Breakfast

Well, I had a little break over the holiday season, did a little dog-sitting, but now it is time to get back to it!

The next couple chapters are pretty short, only a scant few pages of material. But that’s good, as it allows me to prepare myself for the following chapters, where we’ll have to really delve deep into capital-t Theology in the Chapel and the Sermon. But for now, light situational comedy with Ishmael and co.

SUMMARY: Ishmael goes down to breakfast. He considers yelling at the landlord over the way he tricked Ishmael into sleeping in the same bed as Queequeg, but decides to take it all in good humor. At breakfast, he finds that all the other boarders are whalemen, who have been back in port for various amounts of time. They are unexpectedly quiet and reserved, almost embarrassed to talk to each other. Queequeg eats only raw steak at breakfast, then settles down to a smoke in the parlor. Ishmael decides to head out for a walk around the town.

Ishmael starts off this chapter with an acknowledgment that you have to be able to laugh at yourself. He realizes that the landlord was “skylarking him not a little in the matter about [his] bedfellow”, but that’s all in the past now. Especially now that Ishmael and Queequeg are the closest of pals after a single night together. All’s well that ends well, and there’s no use holding a grudge, no reason to take yourself so seriously.

At the breakfast table, we get a bit of fun about the rowdy, tough, burly group of boarders. All of them are hard-bitten, experienced whalemen, of various ranks and jobs. They wouldn’t think twice about jumping in a boat to make direct battle with the largest living beings on the face of the earth, but they are completely lost when it comes to making conversation over the breakfast table.

Melville makes reference to two explorers in this bit, Ledyard and Mungo Park. The Ledyard referenced here is assuredly John Ledyard, an American explorer from around the revolutionary war, famous for a couple things.

For one, he was on Captain Cook’s last voyage as a British marine (this was before the revolutionary war started), and witnessed his death in Hawaii. He was sent to Canada to fight the Americans in 1780, but quickly abandoned his post and went home to Connecticut. Not so he could fight on the other side, but so he could write a memoir about being on Cook’s last voyage, which ended up being the very first book protected by American (and Connecticut) copyright.

Then, he was commissioned by Thomas Jefferson (not yet the president) to explore the western parts of the North American continent. To do this, he took the easiest, most direct route: across the Atlantic ocean, through Europe to Russia, then all the way across Siberia so he could island hop along the Aleutians to Alaska and down to the Pacific Northwest. He got all the way across Siberia, then had to stop for the winter, was arrested, and deported aaaaaall the way back to Poland.

So that was a bit of a setback.

But, on the fame of his voyage with Captain Cook, and subsequent memoir, he got another exploration job, this time in Africa. He was to find a way from Egypt across to the Atlantic coast. But the expedition was beset with delays, poor old Ledyard had to hang around Cairo for several months. In that time, he accidentally poisoned himself with sulfuric acid, and was buried in an unmarked grave on the banks of the Nile. Poor soul!

Mungo Park was some Scottish guy who explored the interior of Africa, before drowning in a river. Also, the name of a famous golfer and golf course designer from the 19th century.

Anyway, the whole point of referencing them is that their famous voyages were not of the sort that gives a man a great command of conversation at the breakfast table, as it failed to do for the brawny boarders of the Spouter-Inn. They are all silent as they eat, Queequeg most of all, as he pulls his raw beefsteaks onto his plate with his very own harpoon, which he used to shave only a few minutes earlier.

Under most circumstances, that would probably be considered quite rude, bringing a great big lance to the dining room table. But, Queequeg commands himself with such coolness that he is, by definition, genteel. It just goes to show, if you stay calm and act like whatever you’re doing is exactly correct, nobody will dare question you.

A good lesson for life, in general. Don’t worry overmuch about whether you are doing the “polite” or “correct” thing, socially speaking. Just act with confidence, and it will see you through anything.

I’m still considering moving this blog to another site, but for now things to be relatively stable here, so I’ll just keep going and not worry for the time being.

As always, you can follow along with the full text from Gutenberg dot org. Until next time, shipmates!

#moby dick#Moby-Dick; or The Whale#herman melville#ishmael#queequeg#beefsteaks#john ledyard#mungo park#manners#19th century

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 4: The Counterpane

Pretty short chapter this time, this book can be like that. One chapter can be nigh on a hundred pages long, and another only a few scant paragraphs. But you can always trust in old Ishmael (or rather, Melville) to have some point to his chapterage, even if it is, at times, a bit obscure. Much like the name of this chapter, an old fashioned word that simply means “blanket” or “quilt”.

SUMMARY: Ishmael awakes to find himself in the loving embrace of Queequeg, and has trouble waking him up. Queequeg finally gets up, and gets dressed in a strangely roundabout and comical way, then goes down to breakfast.

So, it’s time to talk about Queequeg. This is a subject where context can be very helpful when it comes to being charitable to Melville in his depiction of this famous south pacific islander. Melville was quite familiar with the region from which Queequeg hails, having spent many years there as a sailor in his youth. Indeed, the books that actually made him money as an author (Moby Dick was a miserable flop on publication) were rollicking south-seas adventure stories, called Typee and Omoo. So this isn’t just a random choice, but rather something that Melville can speak of from personal experience.

Now, in the last chapter, Ishmael decided to give in and sleep in the same bed as Queequeg with the logic that “it is better to sleep with a sober cannibal than a sober christian”. This opened up the ol’ can o’ worms regarding “savages” just a crack, which this chapter then blows wide open. The dichotomy between savage and civilized people is taken for granted, and Queequeg is talked of as being between the two states of existence.

“Savage” is, of course, the epithet used for those people who were not a part of the great European “civilization” that had risen to dominate basically the whole world at this point. It sets apart those who had not been absorbed into this monoculture, those who had yet to be broken by the wheel of colonization. The classic trope, employed a bit here, is to say... maybe these so-called savages are actually... better than us, more pure, closer to the earth, etc etc.

This is all pretty questionable, the kind of thing that you see in a book from the 19th century and just roll your eyes at, and endure. However, the characterization of Queequeg is a bit more nuanced and interesting than the simple noble savage archetype that we all know and dread. The main thing about Queequeg is that he’s not stupid, just different. He’s incredibly competent at everything he tries his hand at, he just has a different set of assumptions about how the world works.

This is the thing that Ishmael has no problem with, fundamentally. People are allowed to be different, the nature of those differences are basically immaterial as long as they don’t get in the way of living your life.

I’ll get back to this topic later, when it becomes more relevant again.

Anyway, this chapter also has one of my favorite long, meandering asides. When Ishmael is pinned in his bed by Queequeg’s loving, homoerotic, husbandish embrace, he is reminded of a very evocative memory from his childhood. The story is basically a time when he experienced sleep paralysis, after being sent to bed early on the longest day of the year. He awoke unable to move, with a sense of some mysterious figure in the room with him. Textbook sleep paralysis, pretty interesting to see it crop up here. Ishmael says that being stuck under Queequeg’s arm was similar, but not terrifying at all, just annoying.

There is quite a bit of this sort of content in this book, that comes off as not a little bit queer to our modern eyes, in the modern interpretation of that word. But, the past is a foreign country. In the 19th century, such affection between male friends was simply the norm. Of course, you’re free to read into it all the subtext you want, nobody’s gonna stop you.

Two more fun things to note before we finish up, both from the breakfasting scene at the end of the chapter:

1. Queequeg shaves himself with his harpoon. This is described as “using Rogers’s best cutlery, with a vengeance”. This is one of those things your eyes probably just slide right over and say “oh sure, some reference to some old timey thing, whatever”. And indeed it is, a reference to William Hazen Rogers, a famous silversmith who designed many silverware patterns that are still used to this very day.

2. “With a vengeance”? It seems a bit odd to see that little idiom show up in a book some one hundred and sixty years old. But, as it turns out, “with a vengeance” has been a part of English common usage since the 16th century, as far as I can find. I had always assumed it was coined by the title of the Die Hard sequel, but it makes sense that it’s old, vengeance is certainly an old idea.

Well! I managed to wring a bit of blood out of that short, sweet chapter. The next few chapters are also pretty short, but I’m sure I’ll find something to go off about in them. As always, you can follow along with the full text of this ancient tome on Project Gutenberg.

Until next time!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 3: The Spouter-Inn

Here we go, this is the chapter where the book really kicks into gear. There’s a lot that happens, but one particular section is very intriguing to me. It connects deeply to my whole thesis for interpreting and understanding the book, as a fictional artifact and a work of literature.

SUMMARY: Ishmael enters the Spouter-Inn, meets the proprietor, and discovers that all the rooms are booked. But, he is offered to share a bed with one patron who has not yet returned that evening, a harpooneer who is off “selling his head”. Ishmael agrees, reluctantly, and settles in for the evening. He eats dinner with a taciturn and silent collection of fellow sailors, and then meets a raucous grew returning from a long whaling voyage. Ishmael decides he really can’t deal with sleeping two to a bed, and tells the landlord he will sleep on a bench in the parlor instead. But, the bench proves too uncomfortable, so he is forced to go up to the harpooneer’s room. At first, Ishmael is certain that the harpooneer will no return that night, but he eventually shows up, and is Queequeg, a pacific islander covered in strange tattoos, with strange habits. Ishmael first yells in alarm when Queequeg finally enters the bed with him, but is calmed down by the landlord, and they go to sleep together.

Whew! There’s a lot, and I’ve even left out quite a few little details here and there. But, what I want to focus on is The Oil Painting, which I didn’t even mention in my summary, as it isn’t really something that happens, per se.

Ishmael mentions that when you first enter the Spouter-Inn, as he does, you are greeted with a huge oil painting in the entryway. This oil painting is positioned in an odd way, not clearly lit, and extraordinarily vague, dark, and confusing to the eye. He describes trying to puzzle out what, exactly, this painting is depicting, and the effort it takes to come to any satisfactory conclusion.

It takes several visits, opening windows to literally shed more light on it, conferring with other patrons of the inn who have also studied it. And even then, only wild and bizarre theories present themselves, until you really sit down and study it very, very closely.

He finally figured it out, in the fullness of time, and discovered that it was a ship foundering in a storm, with an enormous whale attempting to leap over it, but impaling itself on the masts.

This painting works as a metaphor for the book itself. Or rather, the painting is the events that the book is about, a series of strange and obscure events, difficult to interpret and hard to reckon with, at the end of the day. After all, everyone famously has their own private theories about what Moby Dick himself represents. The anecdote about the painting is another example in the theme of dutiful scholarship, which has been running through this book since before it even began properly!

The section about the oil painting is a central part of my personal theory about this book.

FIRSTLY, it was written by a much older, more experienced Ishmael, after a lifetime of whaling voyages. In this particular little anecdote, he speaks of many subsequent visits to the Spouter-Inn, and we see that it is a favorite haunt of sailors just returned from whaling voyages. This would also explain his expertise with the finer points of whaling, as seen in non-narrative chapters later in the book.

SECOND-OF-LY, the book, as a fictional artifact, which is to say a book written by Ishmael about his experience on the Pequod, is an attempt to make sense of this experience through the project of writing down both those experiences as he understands them, and everything he knows about whales and whaling. Not to spoil things, but at the end Moby Dick sinks the ship and everyone is killed except for Ishmael. This shatters him, utterly, and he spends the rest of his life obsessing over whaling, and that voyage in particular.

This feverish scholarship, the need to really understand the entirety of what happened on this ill-fated voyage, is what the book is. But, Ishmael knows that he cannot actually fully comprehend what happened on that original voyage. This is all idle, the project is ultimately a failure, he cannot fully explain the actions of even a single whale, much less systematize the existence of their whole race.

But that doesn’t mean he’s not going to try. As with the oil painting, he believes that it is possible to understand the world through thorough enough study, he just doesn’t believe that this effort that he’s put forth is enough. If only he could keep revisiting it! Shedding new light, and interviewing others who were there! But the world is too big and chaotic, it is not confined to the borders of a simple painting.

Anyway, a bunch of other stuff happens in this chapter too, I guess.

There’s a weird bit with this other whaling crew that has just come back into port. One member of the crew, one Bulkington (yes, really), quietly walks out. His character is attended, in the book, with a lot of significance and pomp. This mysterious hero is mourned by his friends, who leave to chase after him as soon as he leaves. Oddly, Bulkington will show up again in exactly one chapter, and exit the narrative just as mysteriously then.

The description of trying to get comfortable in a strange place under less than ideal circumstances is very, as they say, #relatable.

I now took the measure of the bench, and found that it was a foot too short; but that could be mended with a chair. But it was a foot too narrow, and the other bench in the room was about four inches higher than the planed one—so there was no yoking them. I then placed the first bench lengthwise along the only clear space against the wall, leaving a little interval between, for my back to settle down in. But I soon found that there came such a draught of cold air over me from under the sill of the window, that this plan would never do at all, especially as another current from the rickety door met the one from the window, and both together formed a series of small whirlwinds in the immediate vicinity of the spot where I had thought to spend the night.

Who hasn’t been there?

The close, deep friendship between Ishmael and Queequeg is central to the next few chapters, so I won’t get into it here. The phonetic accent that Melville writes for Queequeg is... a bit unfortunate, but not too bad. It’s a thorny issue, that I will attempt to unravel with all due sensitivity in the near future.

That’s it for this chapter! As always, you can follow along with the book over at Project Gutenberg. As tumblr is currently going down in flames, I am considering setting up an external blog for my writing, I’ll be sure to link it here when it goes live, once I decide upon a proper platform.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 2: The Carpet-Bag

Here we find the start of the proper narrative, though that doesn’t mean we’re going to leave aside the asides and classical allusions. This is still definitely being narrated by an older Ishmael, and he lets you know it on a constant basis.

First off, I’m just gonna give a quick summary of the things that happened in this chapter, and then take a closer look at some interesting bits.

SUMMARY: Ishmael decides to “quit the good city of old Manhatto” and go to Nantucket to find a whaling voyage to join. He arrives in New Bedford on a saturday night, and discovers that the next ferry isn’t until monday morning. Wandering the icy, December streets, with little money in his pocket, he seeks a suitable cheap inn to rest at. Along the way, he stumbles (literally) across a church full of black people, in the middle of a service. Near the harbor, he finds the Spouter-Inn, a dilapidated old house whose sign has a suitable “poverty-stricken creak to it”. Ishmael decides to head inside.

Now, one thing that’s interesting about this particular chapter is the title of it. Carpet bags have a certain cultural implication in America, particularly in the south, where the northerners who came to oversee the Reconstruction after the civil war were called “carpetbaggers”. It has an implication of an outside meddler, who thinks they’re better than you. I, of course, first heard the term from the mouth of Foghorn Leghorn, late of the Looney Tunes, on saturday mornings, as you do.

But, none of that actually applies to the use of the term “carpet-bag” in this chapter, because this book was written in 1850, some 15 years before the civil war. A carpet bag is just the thing that Ishmael packs his things in. It’s literally a bag made out of carpet, rather common luggage in the 19th century. It’s good to keep in mind this context as we move forward. There are one or two segments involving black characters and phonetic accents that are, as the kids like to say these days, quite problematic. But that sort of thing was in the air, literarily speaking, at the time. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published the same year as Moby Dick.

Anyway, I’m getting off track. There will be plenty of time to mull over such... shall we say, regrettable passages, when the time comes.

This chapter has a lot of great imagery around darkness and cold. The frozen, dark streets of New Bedford, lit by only a few small lights here and there, “like a candle in a tomb”. This leads into one of the main biblical metaphors, of which there are several.

Upon finding the Spouter-Inn, and deciding it looks cheap enough, Ishmael first mentions that it is situated on a sharp corner, where it is hit directly by the wind. He calls the wind “Euroclydon”, and then goes on to talk about how it is an awful, tempestuous wind that is a terror to those left out in the cold, but a comfort to those who can remain indoors. Using another, different biblical analogy, he compares the situations of Lazarus and Dives, one suffering in the wind with no relief, and the other enjoying luxury in his cozy house.

Ah, I said a second, but the wind Euroclydon is itself a biblical analogy. It’s the very wind that sunk Paul’s boat on his way to Malta in the book of Acts (27:14). This wind is called by name in that book, being the traditional term for cyclonic winds from the northeast in the mediterranean. This has absolutely nothing to do with the parable of Lazarus (not that Lazarus, the less famous one) and the rich man (traditionally called Dives). Talking about Euroclydon is just a biblical reference for the sake of it, and Ishmael (or Melville) does revel in that.

Throughout this book, Melville makes use of biblical references as a matter of course, both well-known and obscure. Indeed, his very writing style is influenced greatly by the King James Bible. It adds a degree of bombastic flair to what is otherwise a very plain story about a sea voyage.

There is more going on with the bit about Lazarus and Dives, though. Another reference to the predestined nature of life, and how you can’t change your fate.

But it’s too late to make any improvements now. The universe is finished; the copestone is on, and the chips were carted off a million years ago. Poor Lazarus there, chattering his teeth against the curbstone for his pillow, and shaking off his tatters with his shiverings, he might plug up both ears with rags, and put a corn-cob into his mouth, and yet that would not keep out the tempestuous Euroclydon.

Also using this metaphor to talk about the improvement of humans, through the notion of stopping all the holes to keep out the wind. But, concluding that it’s simply too late now. This is also where we start to get the theme of luxury and comfort being most enjoyable when they are juxtaposed with harshness:

What a fine frosty night; how Orion glitters; what northern lights! Let them talk of their oriental summer climes of everlasting conservatories; give me the privilege of making my own summer with my own coals.

Now, there is one last paragraph here that I am quite puzzled over. I can’t quite make out what Ishmael (or, rather, Melville) is on about.

Now, that Lazarus should lie stranded there on the curbstone before the door of Dives, this is more wonderful than that an iceberg should be moored to one of the Moluccas. Yet Dives himself, he too lives like a Czar in an ice palace made of frozen sighs, and being a president of a temperance society, he only drinks the tepid tears of orphans.

It’s a very evocative image, and a fun little bit of prose. But... what? Is this like some manner of joke about how the bible isn’t a true account of things that actually happened? With a joke about temperance societies thrown in, for good measure? There is no more context, the chapter ends after the next paragraph, where Ishmael decides to head inside, and it is never brought up again.

So, like I said, context is important, and I’m clearly lacking some here. Perhaps it is some sort of contemporary joke, lord knows Melville loves to make all sorts of classical and, to him, modern references and asides. But, the information to properly interpret this has been lost to the ravages of time! It remains only as a perplexing bit of prose, evocative as it is enigmatic.

Thanks for reading, as always you can read along with any number of fantastical futuristic electronical reading devices using the computer files available at yonder website, named for the famous German inventor of the very printing press that was formerly used to print the very first printed books and spread knowledge to the common people of the world, or at least the northern climes that are now, as then, designated Europe.

Come back next time for a real monster of a chapter, where a lot of things happen!

#moby dick#moby-dick; or the whale#ishmael#new bedford#nantucket#manhatten#carpetbagger#my writing#chapter by chapter#euroclydon#lazarus#herman melville#2

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 1: Loomings

Well, there it is, the most famous opening line in all of lit’rature. Personally, I never found it all that impressive. It’s been quite over-exposed, removed of all context. Whatever power it once had has been dispersed throughout our general culture. It’s more of a Thing that you’re supposed to Respect, rather than an organic piece of writing, anymore.

Keep reading

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Etymology & Extracts: Lord Help Me, I’m Back on My Bullshit Again

The book Moby Dick, or to give it’s proper, full title, Moby-Dick; or, the Whale, is my favorite piece of writing that exists. I think that if you give it a chance, you’ll find that it is not the chore that it initially appears. Indeed, from the very beginning, it’s positively brimming with character, crackling with folksy energies.

Keep reading

7 notes

·

View notes