#茶筅

Photo

New arrival! Vintage chasen (bamboo whisk), an essential item for Japanese tea ceremony. Made by Kizo Nakata in Nara prefecture. Nara is known for artisan chasen making. Now available on our online store and at our Parisian boutique. #maisonsatoparis #chasen #japaneseteaceremony #japaneseartisan #madeinjapan #matcha #bamboowhisk #japaneseteaware #茶筅 (à Paris, France) https://www.instagram.com/p/CkqK33yoAjA/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#maisonsatoparis#chasen#japaneseteaceremony#japaneseartisan#madeinjapan#matcha#bamboowhisk#japaneseteaware#茶筅

0 notes

Photo

. #茶筅供養 #濃茶 #茶道 #chado #wayoftea #teaism #茶の湯 #chanoyu #抹茶 #matcha #greentea #japanesetea #tea #星窓 #星窓茶道 #tokyo #japan #zen #禅 #インスタ茶道部 #tea #wabisabi #濃茶 #盆点 #唐物 #一日集中稽古 (Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan) https://www.instagram.com/p/CnEfHb8vWjD/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#茶筅供養#濃茶#茶道#chado#wayoftea#teaism#茶の湯#chanoyu#抹茶#matcha#greentea#japanesetea#tea#星窓#星窓茶道#tokyo#japan#zen#禅#インスタ茶道部#wabisabi#盆点#唐物#一日集中稽古

1 note

·

View note

Text

Common Sense Kings Headcanons

(Angst-free only.)

As a Whole:

"Common Sense" is a lie. They share one braincell and Kan keeps it in the confiscated phones drawer. (He hasn't trusted them since the Incident. No, I will not elaborate.)

They're all great swimmers, except Tsuburaba. The kanji in Awase's name all relate to water — bubbles, rapids, ocean, and snow; Kaibara is definitely the type to use his Quirk as a boost (and it just seems helpful in general); and for Rin, Chinese dragons are associated with water, unlike Western ones. Tsuburaba, meanwhile, is mostly associated with air.

Video game nights usually end in disaster. That's why they mostly play Mario Kart, the least rage-inducing game ever.

Awase:

Sometimes, he Welds together little mixed media sculptures. Metal bits, googly eyes, Rin's scales, that sort of thing. He isn't very good at it, but then, he doesn't have to be. It sparks joy.

Also decent with mechanics. He, Yaoyorozu, and Hatsume would make a great team.

Has a lot of scars from all the dumb shit he's done over the years — and he's proud of every single one of them. Even the dumbest ones. It inadvertently helps some of his friends feel better about their own.

Cheats at origami.

Kaibara:

Loves green tea. This is based on two puns: Sencha (煎茶), the most popular green tea in Japan, and chasen (茶筅), the bamboo whisk used to make matcha. (There are so many puns you can make on the name Sen, it's great.)

The best dancer of the four — or, the only good dancer. The other three suck.

A contortionist in every way except professionally, with no qualms about showing it off. He's got the most fucked-up joints you've ever seen. He can even turn his head around like an owl. Fear him. (Seriously, look up contortionists, they're awesome.)

Tsuburaba:

Has the spice tolerance of a wet chicken nugget. You could kill him with a singular Dorito. The other three refuse to let him live this down.

Obsessed with practical effects in movies and plays. Props, clever set design, you name it. He's even experimented with using his Solid Air for something similar, though he hasn't done it in a while. In a movie production AU, he'd definitely be in charge of that.

When Kan doesn't have it, Tsuburaba holds the braincell. He's objectively a terrible choice, yes, but process of elimination rules. And yes, this is because of the Incident.

Rin:

Many thoughts, head still empty for some reason.

His favorite animal is the koi fish.

Almost won the class representative election purely by promising to teach the class Mandarin swear words. Kan was not happy.

Can and will make up a bullshit idiom. What are you gonna do about it? Fact-check him? Take your phone out and Google it? In front of the teacher?

#headcanons#mine#class 1b#class 1-b#common sense kings#awase yosetsu#kaibara sen#tsuburaba kosei#rin hiryu#on another note tsuburaba's costume should've been an embellished flight suit

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

What better way to say thanks than with a humble bowl of tea. Happy Father's Day! 🍵 . . . . . #matcharitual #matchamoment #matchamadness #matchalife #matchamornings #matchalover #matchatime #matchalovers #teatime #matchaaddict #matcha #matchatea #matchaholic #matchameditation #matchagreentea #matchabowl #teabowl #usucha #oribe #chawan #薄茶 #茶碗 #茶道 #抹茶 #茶筅 #日本茶 #織部 #有機抹茶 — view on Instagram https://ift.tt/sUfbA0L

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

This hairstyle is not chasenmage, and Sengoku samurai rarely wear this

I’m talking about this hair:

(screenshot from Kirin ga Kuru)

This is not specifically about Nobunaga or anything, but 90% of the Nobunaga I see in Taiga drama and movies usually has this hair style, and I want to talk about it. There were some drawing guides I’ve seen online that mistakenly label this hair as “chasenmage”, and it’s somewhat misleading.

Chasenmage 茶筅髷, literally meaning “tea whisk hair”, is one of the hairstyles commonly worn in the Muromachi and Azuchi-Momoyama period aside from the folded topknot (orimage/chonmage). The hair is tied tightly with strings, leaving a small tuft at the end, making it resemble a tea whisk. However, even a high-angled chasenmage doesn’t go as far as stick straight up like seen above.

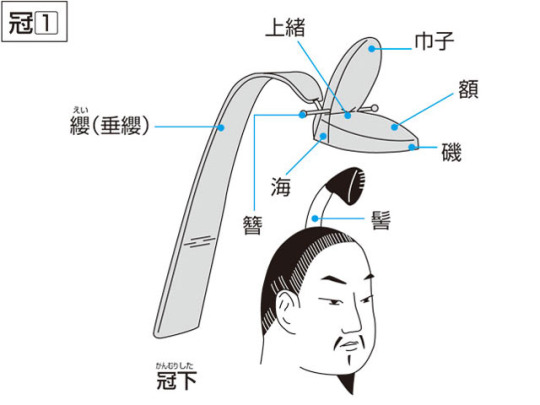

That being said, I say they “rarely” wear the sticking-up style, not “never”, because this hairstyle is actually "real”. It’s not a made-up style invented by Kabuki or movies, it’s just... incorrectly applied. This hairstyle is called kanmuri-shita no motodori 冠下髻 or hitotsu motodori 一髻. It’s the hairstyle worn under the kanmuri (court cap):

(image from Kotobank dictionary)

So if you want to be "accurate”, it’s fine Nobunaga or some other daimyou wears this hairstyle sometimes, but only if you’re showing they’re in the process of getting dressed or undressed from courtly attires (for meeting with the shogun or other courtly business).

It’s one thing if the character is the emperor or court nobles, as the caps are often part of the daily attire. It would make sense that they might keep their hair in kanmuri-shita style even in leisure. However, Sengoku daimyou wear their hair mostly in the folded topknot style, and there is no reason for them to constantly wear kanmuri-shita hair. And, once more, the kanmuri-shita is not the chasenmage that Sengoku samurai did frequently wear.

(Emperor Seiwa, shown with his hair in the kanmuri-shita style. From the Ban Dainagon Ekotoba 伴大納言絵詞 picture scroll)

Picture from Teijou Zakki 貞丈雑記, written by Ise Sadatake around 1763-1784, also describing that this hairstyle is meant to be worn under a hat (either an eboshi or a kanmuri, as mentioned above)

I can’t trace where/how it began, but at some point it seems that Kabuki actors starts wearing that hairstyle in their performances:

Ukiyo-e of Kabuki actors then influence ukiyo-e depictions of “historical events” of the Sengoku. Then, when people start making movies about Sengoku samurai maybe in the 50s and 60s, ukiyo-e and Kabuki costumes are probably the easiest source of reference, resulting in this long-standing “trend” to give Sengoku samurai this hairdo.

(Nobunaga wearing that now-“iconic” hairstyle in an ukiyo-e by Yōsai Nobukazu 楊斎延一)

Meta-wise speaking, it’s likely that studios maintain this “wrong” hairstyle to save on budget. It’s better to just reuse old wigs rather than spend more money to make a new batch of historically-accurate wigs. However, I don’t really see any reason for illustrated media maintaining this, other than “maybe the artist just didn’t know”. Unlike the image of Nobunaga wearing European armour, there is no real branding attached to this hairstyle, so there is no specific need to keep drawing this style. Far as I can tell, Sengoku enthusiasts are equally fine with seeing samurai wearing just a “normal ponytail”.

Or, if not, something like this:

The hairdo Koei likes to use for their Nobunaga’s Ambition portraits may not necessarily be an accurate chasenmage either, but it’s “less wrong” than the kanmuri-shita.

We end with what a “correct” chasenmage looks like, as depicted by paintings from the 16th century:

Some attendants from Nanban Byoubu by Kanō Naizen 狩野内膳 were shown wearing chasenmage.

Falconers from the Rakuchuu Rakugai screen, by Kanō Eitoku.

*) The third person behind them that I did not mark is angled oddly, so I wasn’t able to identify if that was a chasenmage (more stiff, secured with more strings) or just a “floppy ponytail”.

Modern illustration for clarity, provided by Kotobank online dictionary.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

2023年7月12日(水)

一週間前に申し込んだ新幹線の予約、午前8時10分に第一希望がとれたとのメールが届いた。早速アプリから、ICカードの割当をする。今まで気にしたことは無かったのだが、ツレアイは以前からSuica利用、私は先日Icaocaに変更、するとカードの番号が<JW80F>と<JE80F>、なるほど西日本(West)と東日本(East)と区別されているのか。これで Apple Watch ひとつで自宅から桜木町まで楽ちん乗車、むふふふ。

4時30分起床。

日誌書く。

5時30分、シャワー。

朝食、洗濯、弁当*3。

空きビン缶、45L*1。

ツレアイの職場経由で出勤する。

月曜日の<情報機器の操作Ⅰ(看護学科)>の採点作業、Excelファイルをチェックするのだが、学内フォルダなら問題ないが、GoogleDriveにコピーすると100%互換ではない。このことを忘れていたために、途中までの作業が無駄になってしまった。

水曜日は2限・3限<情報機器の操作Ⅰ(栄養学科)>、月曜日と同じく Excel の試験。しかし、欠席者が多くて心配だ。

3限終わりですぐに帰宅する。

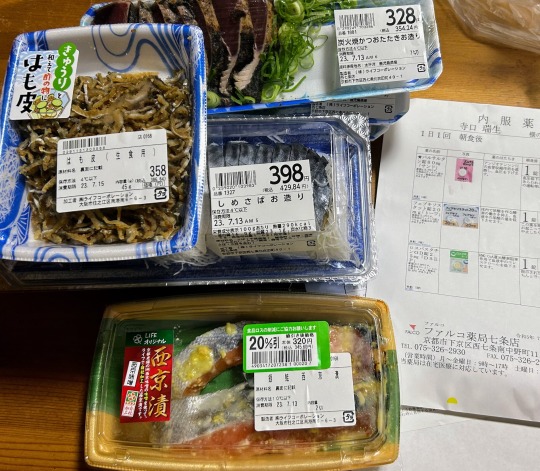

月曜日にツレアイに代行を頼んだ処方箋を持ってファルコ薬局で10日分の薬をいただく。そのままライフ西七条店へ、肉系が続いていたので今夜は魚にする。外に出た途端に激しい雷雨、傘を持っていて良かった。

昨日点滴をしたココ、今日はカリカリと音を立ててご飯を食べている。

ツレアイも早めに終わって一緒に夕飯、息子たちには冷やした白ワイン、私は八海山を冷やでいただく。

テレビ視聴。

「まっすぐ清らか 竹」

初回放送日: 2023年7月12日

「竹の寺」と呼ばれる京都の寺。美しい竹林を作り上げる手入れとは?▽名人の心意気が生み出す「京銘竹」の世界▽さまざまな物語とともに受け継がれる「茶杓(ちゃしゃく)」。千家十職の黒田家の見極めとは?▽室町時代から500年以上伝えられてきた「茶筅(ちゃせん)」の技▽建築家・隈研吾さんが語る「竹と日本人」▽世界が注目する巨大な「竹アート」。伝統と現代を融合させる製作現場に密着!<File584>

放送日が変更になったことを知らなかったのだが、運良く見ることが出来た。

片付け、入浴、体重は2日前から100g増、いかんなぁ。

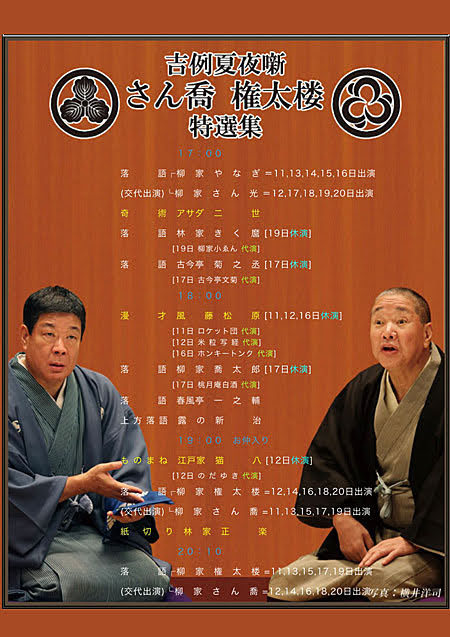

鈴本夏祭りの番組が発表されたとのこと、予約開始は7/29(土)13時、8/12(土)は何としても行くのだ。

久しぶりに3つのリング完成、やはり気分が良い。水分は、1,400ml。

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Repost @marutamaseicha

・・・

【 緑茶じるこ体験 】2023年1月からはじまる、新メニューのご紹介です。まるたま製茶の農薬無散布の緑茶をねりこんだ、緑茶あんを使ったお汁粉づくりです。もちもちの生麩と、ポリポリ食感の炒り玄米、そしてちょっぴりお塩がアクセントです。

温かいほうじ茶付き。

◾️1月の体験メニュー 各500円税込

•緑茶じるこ体験 new

•お茶筅で緑茶ラテづくり

•お煎茶体験

1月はお正月らしく和を意識したメニューです。

#Instagram#tea#japanese tea#green tea#hojicha#matcha#japanese food#japanese sweets#food#お茶#日本茶#ほうじ茶#緑茶#抹茶#お汁粉

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

高架ができるのだろう。

作りかけの柱が茶筅みたい。

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 7 (23c), Appendix 2: Kaki-ire [書入].

○ Kaki-ire [書入]:

The chasen-tōshi should also be understood in the same way as what has just been said [with regard to the momi-te]¹.

When [performing the chasen-tōshi], if the tines of the chasen become too soft, it will not be possible to tap it [audibly] against [the rim of] the chawan². And again, during the winter (and at other such [times of the year when it is cold]), if strongly boiling water is poured into the chawan, [we] should always be concerned that it does not crack, so it is not a good idea to tap [the chasen against the rim of the bowl in that season of the year]³.

This [tapping the chasen against the rim of the chawan] is also based on the rules that describe the rituals of the Shingon and Tendai sects⁴. When the vessel is tapped, if that which [it contains] is [ritually] unclean, it is purified: this is found in the ritual for blessing holy water⁵.

While the morpheme⁶ “RAM” [ रँ, 囕] is being intoned, [the vessel containing the water that will be blessed] is tapped twenty-one times with the sanjō [散杖]⁷. And then, while chanting “VAM” [ वँ, 畔], [the vessel] is tapped twenty-one times⁸.

Afterward [incense, flowers, and other] offerings are made [to the Buddha], following the same procedures, while chanting “HŪM” [ हूँ, 𤙖]⁹. From this [ritual], one feels that every impurity has been completely cleaned away¹⁰.

The chawan is passed [back and forth] between [the host and his] guests again and again; yet only one [chawan] is used¹¹. [This might make them feel uncomfortable,] particularly when the guests do not know who may have been drinking before them¹². Because this might seem unpleasant, the three taps [of the chasen against the rim of the chawan] at the beginning [of the temae] seem to make [us] think about the “RAM-VAM-[H]ŪM” of the triple invocation¹³. And again, later [in the temae] when rinsing [the chasen], [tapping the chasen against the rim of the bowl twice reminds us of] the double-invocation of “RAM-VAM” -- and with that, [the chawan] will be cleansed¹⁴. Borrowed [originally] from the Shingon [ritual], we [also] do things in this way¹⁵.

([Shibayama’s note:] “RAM-VAM” refers to fire and water.)¹⁶

_________________________

◎ This kaki-ire , which discusses the practice of allowing the handle of the chasen to tap against the rim of the chawan during the performance of the chasen-tōshi [茶筅通し], is not found in the Enkaku-ji manuscript of Book Seven of the Nampō Roku. Nevertheless, both Shibayama Fugen and Tanaka Senshō include this text in their commentaries (Tanaka places it after the longer version of the text, as is most appropriate, since that is the version to which it was originally appended), so I felt it would be good to include it in this translation as well -- leaving it up to the reader to decide how important the material is*.

The way this kaki-ire is written suggests that it was added much later than many of the other emendations that are found throughout the different books of the Nampō Roku, and clearly reflects the machi-shū style of temae that appeared during the seventeenth century, following Sōtan’s rise to prominence.

With respect to this text, Tanaka writes “[this] is a brief note appended to the text, which is very relevant. The [form of the] chasen-tōji [茶筅湯じ]† was derived from the rules detailing the Shingon kaji-kitō [加持祈禱]‡ ritual. This idea has been completely deleted from the popular books [about chanoyu]. [Furthermore,] no mention of this is made in any of the [collections of] secret teachings, not even in Hiden kū-ka-jō [秘伝九ヶ条]**. It is regrettable that Jitsuzan koji [実山居士]†† misrepresented the text [of entry 23] in many places [through his numerous editorial deletions].‡‡”

Nevertheless, we must take this lament with a grain of salt, since it was precisely esoterica of this sort that held a fascination for Tanaka Senshō***

I would like to thank Søren M. Chr. Bisgaard Sōen [宗園] sensei (who also uses the Japanese-language name Bisugō [飛壽胡]), in Kyōto, for his help reading the three Sanskrit morphemes that are found in this kaki-ire, as well as for his very detailed explanations of their meanings.

__________

*As I mentioned in the first appendix (at the end of the previous post), this entry (and so, the kaki-ire that was appended to it) represents the machi-shū perspective that was supplanting Rikyū’s own teachings in the years following his death, in an effort to “restore” chanoyu to the state it had been in during Jōō’s middle period (that is, during the decade or so before Rikyū returned from the continent toward the end of autumn in 1554) -- or, at least, that is what the machi-shū followers of Imai Sōkyū believed they were doing.

According to Rikyū’s own densho, the chasen should not produce an audible sound when it is rested against the rim of the chawan during the chasen-tōshi.

†Chasen-tōji [茶筅湯じ] is usually written chasen-tōshi [茶筌通し] (or, chasen-tōji [茶筌通じ]) today. Tanaka’s term means “putting the chasen in hot water,” while the more common expression means something like “to look the chasen over.”

‡The kaji-kitō [加持祈禱] is a Shingon ritual designed to pray for divine intervention (by the Shintō Gods and the Buddhas), to deliver humanity from sickness and other calamities.

Kaji [加持] is a translation of the Sanskrit word adhiṣṭhāna [ अधिष्ठान ], which means initiations or blessings. Paraphrasing from the Wikipedia article, in Shingon Buddhism, this includes the chanting of mantras, mudras (ritualized hand-gestures), and visualization exercises aim at achieving honzon-kaji [本尊加持] -- union with the enshrined Buddha-form.

Professor Emeritus Minoru Kiyota (1923 ~ 2013), of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, identified three kinds of adhiṣṭhāna in the theory and practice of Shingon Buddhism: mudra, the finger sign [gesticulation]; dhāraṇī, [the chanting of]secret verses; and yoga [...].

**Hiden kū-ka-jō [秘伝九ヶ条] is one of the titles used for the first of the two books of secret teachings that were appended to the Nampō Roku by Tachibana Jitsuzan and the Enkaku-ji scholars. According to Kanshū oshō-sama, access to these two books was even more closely restricted than to the Nampō Roku itself.

††Jitsuzan koji [実山居士] was the name used by Tachibana Jitsuzan after his retirement. His actual name was Tachibana Shigemoto [立花重根; 1655 ~ 1708].

He received the name Jitsuzan koji when he retired and became nyū-dō [入道].

Jitsuzan established the Tōrin-ji [東林寺] (a small sub-temple, consisting of a moderately sized Buddha hall, with residential buildings, a dedicated room for za-zen, a shoin, and the Jisei-an [而生庵] (above) -- a 4-mat tearoom arranged like a yojō-han (with a masu-doko [桝床], a square toko that takes the place of the half-mat, located at the far end of the utensil mat, in the corner of the room) -- which he constructed in front of the main gate of the original Enkaku-ji (now the site of Hakata Train Station) in 1696. The Tōrin-ji still stands on its original site, and Jitsuzan’s grave is located in the garden in front of the main hall.

‡‡Nao honbun ni, shōchū no kaki-ire ari. Kore ni kanren shitaru. Shingon no kaji-kitō no hō yori okoru chasen-tōji no konpon no koto de aru. Seken no rufu-hon ni hako no koto sakujo shite ari. Hiden to shite shimesanu mono ka, Hiden kyū-ka-jō ni mo nashi. Jitsuzan koji, ō-ō kono daiji no bunshō wo kaizan suru wa, ikan ni taezu. [尚本文に、小註の書き入れあり。これに関聯したる。真言の加持祈禱の法より起る茶筅湯じの根本のことである。世間の流布本にはこのこと削除してあり。秘伝として示さぬものか、秘伝九ヶ条にもなし。実山居士、往々この大事の文章を改竄するは、遺憾に堪えず。]

*** Tanaka was a firm believer in the inherent validity of the machi-shū tradition, particularly the version that had been proselytized by Urasenke since the last decades of the nineteenth century, which also featured a pseudo-mystical bent

¹Chasen-tōji ni mo, migi no kokoro nari [茶筌トウジニモ、右ノコヽロナリ].

Chasen-tōji [茶筌通じ] seems to be pronounced chasen-tōshi today. This is the action, during the temae, to ready the chasen for the preparation of koicha or usucha -- a way to “test” its performative ability, as it were. First the chasen is handled in a way that mirrors its use when blending koicha; then it is used to whisk the hot water, in anticipation of mechanics of making usucha. The modern schools also usually include lifting the chasen out of the bowl several times, so the tines may be visually inspected -- though Rikyū, in his writings, appears to have disapproved of this machi-shū practice (preferring for the host to look at the chasen carefully in the mizuya -- since, if any defect is found during the chasen-tōshi, there is really nothing that the host can do to rectify the situation).

Kokoro [心] means mind, understanding, mind-set.

In other words, the host should understand that the chasen-tōshi is a parallel action to the rubbing of the hands together in the momi-te [揉み手]: both actions are intended to elicit ritual purity.

²Chasen no ho no yawaraguru-tame nareba, chawan no tataku ni ha oyobazu [茶筌ノ穂ノヤハラグル為ナレバ、茶碗ヲタヽクニハ不及].

Chasen no ho [茶筌の穂] means the tines of the chasen.

Yawarageru-tame nareba [和らげるためなれば] means "if (the tines of the chasen) become soft...."

Tataku [叩く] means to hit, strike, tap against, and so forth.

Oyobazu [不及 = 及ばず] means not cause (something to happen), unable to achieve (an effect).

In other words, if, while performing the chasen-tōshi, the tines of the chasen become too soft, their resiliency will be lost and the chasen will not be able to tap against the rim of the chawan properly. (The tapping occurs naturally, when the handle of the chasen is released when it is 1-sun or so away from the rim of the bowl, with the tines touching the bottom. The host does not actively tap the chasen against the rim of the chawan, since that could easily damage the bowl.)

³Mata kan-chū nado ha, chawan ni waki-tataru atsui-yu ireba, hibiki-waren-koto* wo osorete, tataku to iu ha arazu nari [又寒中ナドハ、茶碗ニ湧立タル熱湯入レバ、ヒヾキワレン事ヲ恐テ、タヽクト云ハ非也].

Kan-chū nado [寒中など] means during the winter, and at other such times (of the year when the weather is cold). In other words, during the cold months of the year.

Waki-tataru atsui-yu [沸き立て熱い湯] means hot water (atsui-yu [熱い湯]) heated to a rolling boil (waki-tate [沸き立て]).

Hibi-waren-koto [罅割れんこと] would mean a crack (hibi [罅] refers to the physical crack) does not develop (waren [割れん] is a negative form of the verb to crack, to break). Hibiki-waren-koto [ヒヾキワレン事 = 響き割れんこと], on the other hand, would not seem to have any meaning at all†.

Osorete [恐れて] means to fear, to be afraid of (something), to be apprehensive about.

Tataku...ha arazu nari [たたく...は非ずなり] means (the chasen) should not tap against (the rim of the chawan).

The meaning is that, because the host (and everyone else) will be worried that pouring very hot water into the chawan will cause it to crack‡, the host should not subsequently drop the handle of the chasen against the rim of the bowl, for fear of either producing a sound similar to that of a piece of pottery cracking, or reveal the presence of a crack by the dull sound of the tap.

__________

*Hibiki-waren-koto [ヒヾキワレン事] appears to be a copyist’s error. It seems the word should be hibi-waren-koto [罅割れんこと], which would mean “that (the chawan) does not develop a crack.”

That said, while I seem to recall chajin in Kyōto using the pronunciation hibiki [ひびき] when referring to cracked pottery (perhaps referring to the dull sound, hibiki [響き], made when a cracked pot is tapped, and then using this word to refer to the crack itself), I can not find anything to confirm the existence of such a usage -- neither in the modern language, nor in historical, or tea-related, Japanese.

†Hibiki [響き] means a sound, but specifically refers to an echo or reverberation, noise, the quality of a sound related to a specific thing (such as a bell, gunshot, or hoofbeats -- usually heard at a distance), or (though less commonly) the feelings engendered by hearing that sound (or reading about it -- such as the mental impression that reading the word “hoofbeats” produces).

Wareru [割れる] means to break, split, fall apart, crack, and so forth. (Waren [割れん] is a colloquialism that would have been used primarily by men, a contraction of ware-nai [割れない], meaning “to not break,” “does not break.”)

There are no compounds combining hibiki with wareru; and neither pronunciation (hibiki [ひびき], wareru/waren [われる・われん]) has any homonyms that might allow for a different meaning (as is often the case with many Japanese words).

‡According to Rikyū, when a bowl is known to be cracked, or when the host has reason to fear that the bowl will be damaged by the sudden temperature change, several precautions should be taken. The bowl should be gently warmed beforehand in the mizuya, if possible. And then, during the temae, the host begins by pouring half a hishaku of water from the mizusashi into the chawan, after which hot water is added little by little so that the temperature of the bowl will increase slowly (after adding a hishaku of cold water to the kama, and performing a yu-gaeshi, first a quarter hishaku of hot water is poured into the cold water in the chawan; then, after rotating the bowl slowly three times, and without discarding the lukewarm water, a further half hishaku of hot water is added, the bowl is again rotated, and finally the water is discarded). By this point, the chawan will be hot enough that adding a half hishaku of hot water directly from the kama (for the chasen-tōshi) will not damage it. Note that at no time is water heated to a rolling boil ever poured into such a bowl: the temperature of the kama is first moderated by adding a hishaku of cold water, followed by a yu-gaeshi.

However, while Rikyū always warmed the chawan twice (first using a quarter hishaku-full, and, after emptying the bowl, pouring in a half hishaku for the chasen-tōshi), even when it was an ordinary bowl, the machi-shū (acting on the theory that “hot water is expensive,” so minimizing its use was “more wabi”) only poured hot water into the chawan once (to both warm it, and perform the chasen-tōshi at the same time). Thus the apprehension that this statement reveals may have been warranted.

Warming the chawan only once became the general rule under Sōtan.

⁴Kore mo Shingon, Tendai no ka-hō yori motozuki-taru nari [コレモ真言、天台ノ家法ヨリモトヅキタルナリ].

Ka-hō [家法] means a code of behavior followed by all of the members of the sect (to whom it was relevant or applicable)*. Here, the author of this kaki-ire seems to be thinking about the rules governing ritual -- specifically, ritual purification.

Motozuki-taru [基づきたる] means originally, to be based upon (this precedent).

In other words, this teaching was based on ritual practices followed by the Shingon and Tendai sects (to wit, tapping on a vessel as a way of rendering its contents ritually pure).

__________

*More literally, of the family.

The followers of the religion were regarded as being members of the same family.

⁵Utsuwa wo tataite fujō wo kiyomuru koto, kaji-shasui no hō nari [器ヲタヽイテ不浄ヲキヨムルコト、加持灑水ノ法也].

Utsuwa [器] means a vessel, a container (such as, for example, a chawan).

Tataite [叩いて] means to tap on something, tap against something.

Fujō wo kiyomeru koto [不浄を清めること] means the case of purifying something that is impure.

In other words, in the Shingon and Tendai sects, tapping on or against a vessel is a way to (ritually) purify it (or, actually, its contents†).

Kaji-shasui no hō [加持灑水の 法] means the procedure or ritual (hō [法 ]) to bless (kaji [加持]) the holy water (shasui [灑水])* [that is later sprinkled on other things, to bless them].

In other words, tapping (a wand or other object) against a vessel to purify its contents is the ritual (hō [法]) that is followed when blessing holy water‡.

__________

*Perfumed water prepared according to the secret ritual (which will be described hereafter), that is then splashed on things to render them ritually pure.

This blessing by splashing holy water is similar to the practice of sprinkling holy water (on people or objects) in the Catholic religion.

†The way bubbles rise to the surface when a vessel of water is tapped. The bubbles being taken to represent the impurities dissolved in the water, which are released by tapping on the vessel.

The fact that it is what is contained in the vessel that is purified by tapping the vessel with a ritual wand (at least in this example), casts doubt on the veracity of the central argument of this kaki-ire -- that tapping the handle of the chasen against the rim of the chawan somehow purifies the chawan (especially of “bad energy” left in it by previous guests)

‡In Tanaka Senshō's commentary, he writes:

Ima Tendai-shū ya, Shingon-shū de mo, kono hō-hō wo suru ga, kore wo senmon-ka no sōryo ni kiite-miru to, sanjō to iu bō wa, ume no ki de isshaku-hassun-hodo ni tsukuru. Shasui-ki to te mizu wo sakaru-utsuwa ni soete, "ran・ban・un" to iu. [今天台宗や、真言宗でも、この方法をするが、これを専門家の僧侶に聞いて見ると、散杖と云う棒は、梅の木で一尺八寸ほどに造る。洒水器とて水を盛る器に添えて、ラン・バン・ウンと云う。]

“In present day Tendai and Shingon sects, this method [of purifying holy water] is used. This was related to me by a monk who was a specialist [in the conduct of these rituals]. A wand called a sanjō [散杖] is used. It is made from plum wood, and should be about 1-shaku 8-sun long. Beside it is placed the holy-water vessel, filled with water.

“[The Sanskrit morphemes] ‘ram,’ ‘bam,’ ‘um’ are spoken [while the vessel is tapped with the staff].”

Apparently the staff has a yae-renge [八重蓮華] carved on the butt-end of the handle. A yae-renge is a lotus blossom with an inner and outer whirl of petals (this is the kind of lotus blossom on which the Buddha sits, for example), though the carving can be simple (eight lines arranged like a starburst, “✳”) or elaborate (representational).

⁶A morpheme (quoting from the Rochester Institute of Technology) is “a short segment of language that meets three basic criteria: 1. It is a word or a part of a word that has meaning[;] 2. It cannot be divided into smaller meaningful segments without changing its meaning or leaving a meaningless remainder[; and,] 3. It has relatively the same stable meaning in different verbal environments.” Which is what “ रँ, वँ, and हूँ ” are.

I am using this term, in other words, to denominate the Sanskrit elements that are found in this kaki-ire because there is no good word in the English language that actually describes these kinds of entities. Originally I called them “word(s),” but Bisgaard sensei pointed out that they are not, in fact, words. I then tried “calligraphs” (a self-coined term, meaning a written element), but that, too, was vetoed as being too confusing (and, frankly, not a real word -- at least, not when calligraph is used as a noun, as I intended).

Bisgaard sensei’s suggestions were “stand-alone syllable(s)” or “letter combination(s),” but these struck me as both cumbersome and potentially misleading. So, after much consideration, we decided on morpheme as being sufficiently vague to cover all contexts, while (since I suppose that most people are not familiar with this term from linguistics) it would also not be misleading -- since I hope the readers will simply accept it as a term to name these entities, “ रँ, वँ, and हूँ,” rather than exercising their minds wondering what they are.

⁷“RAM”-ji kwan-tote, nijū-ippen utsuri wo sanjō ni te tataki [ रँ 字クハントテ、廿一返器ヲ散杖ニテタヽキ].

RAM [ रँ, 囕] is a Sanskrit morpheme. In the various texts it is represented either by the original Sanskrit morpheme (in the example shown below, Shibayama’s handwritten version is on the left, while a printed form is next), or by the kanji ran [囕] (second from the right). While different pronunciations are given in the different texts (and Shibayama himself appears to be perplexed about what to use*), the closest katakana transliteration would probably be ramu [ラム] (albeit with the final verb dropped), as shown on the left.

Bisgaard sensei has provided the following explanation: RA [ र ], the fundamental sound and basis, stands for the element fire, from which are derived heat, love, desire, and going up.

RAM [ रँ ] is the bija mantra [ बीज मन्त्र ]† of the third chakra [चक्र] Maṇipūra [मणिपूर], which is located at the height of the navel, the height of the stomach. In the ordinary (Japanese) context, it would stand for yang [陽].

Kwan [クワン], or kan [カン] refers to the sound of a bell or gong -- a ding or chime. In this case it seems to refer to a verbal ejaculation (in other words, voicing the sound RAM‡), so I have translated it “intoning” (as below).

Ji [字] means a character or letter, in this case referring to the Sanskrit morphemes.

“RAM”-ji kwan-tote [ रँ 字クハントテ] means while intoning the morpheme “RAM.”

Nijū-ippen [廿一返 = 二十一返] means twenty-one repetitions.

Utsuri wo sanjō ni te tataki [器を散杖にて叩き] means the vessel (utsuri [器]) is tapped (tataki [叩き]) with the sanjō (sanjō ni te [散杖にて]).

As explained (and illustrated) in the previous footnote, a sanjō [散杖] is a sort of wooden wand, 1-shaku 8-sun long, carved or turned from unpainted plum (ume [梅]) wood.

__________

*He indicates the pronunciation with furigana [振り仮名] -- small kana written above or (in this case) to the right of a kanji or other written elements, to indicate its pronunciation -- sometimes as ran [ラン], and sometimes as ramu [ラム]. The same problem is seen in the case of the other two Sanskrit morphemes.

†A bija mantra [बीज मन्त्र] is a one-syllable sound used in meditation or yoga practice. The Sanskrit phrase bija mantra literally means “seed mantra” (which is comprised of two elements: bija means seed, while mantra means an instrument of thought).

‡As a mystical incantation, rather than as a spoken word. This is probably why it is described as being a kwan [クワン].

⁸Mata “VAM” kwan-tote, niju-ichi kaeri tatakite [又 वँ クハントテ、廿一返タヽキテ].

VAM [ वँ, 畔] is another Sanskrit morpheme. Since Japanese does not have a “V” sound, it is usually represented as “B.” For the sake of fidelity to the original Sanskrit, however, I will use “V” in the translation.

Once again, Bisgaard sensei has provided this explanation: VA [ व ] is the fundamental sound and basis, and stands for the element water, from which are derived cold, wetness, and so forth.

VAM [ वँ ] is the bija mantra of the second chakra Svadhisthana [स्वाधिष्ठान], located at the base of the bladder. In the Japanese context, it would be yin [陰].

In the various texts, this is written either with the original Sanskrit morpheme (Shibayama’s handwritten version is on the left, above, while the printed form is next), or by the kanji ban [畔] (once again, second from the right).

The same issue with transliterating the final consonant sound is as mentioned before; but the closest form would seem to be bamu [バム] (which Shibayama uses consistently) -- though Tanaka prefers ban [バン].

⁹Nochi kuyō no mono wo, migi no shirushi ni te “[H]ŪM” to tonaete kyōsu [後 供養ノモノヲ、右ノ印ニテ हूँ ト唱テ供ス].

Nochi [後] means after, afterward, following, subsequently. That is, the offerings made to the Buddha are presented after the holy water has been blessed.

Kuyō no mono [供養のもの] means (to accompany) things offered (to the Buddha)*.

Migi no shirushi ni te [右の印にて] means to replicate the tapping ritual described previously (literally, at the right).

HŪM [ हूँ, 𤙖] is the third Sanskrit morpheme included in this kaki-ire. Bisgaard sensei notes that HŪM [ हूँ ] is generally used as an exclamation†. However here, as elsewhere, it is used as a mystical syllable, included in spells and magical utterances.

A well-known example of this use is in the famous mantra oṃ maṇi padme hūṃ [ॐ मणि पद्मे हूँ]‡ -- “OM Jewel (in the) Lotus HŪM.”

Shibayama represents the sound as umu [ウム], while Tanaka gives un [ウン]. Aside from the initial “H” (which does not exist in Japanese in association with the vowel “u”), both appear ignorant of the fact that this morpheme has a long vowel. Given the limitations of the language, it seems that ūmu [ウーム] might be the best transliteration.

Tonaeru [唱える] means to chant, to recite (an invocation).

Kyōsu [供す] means to offer, to make (ones) offerings.

__________

*These offerings include incense, flowers, votive candles, food and drink.

Kuyō [供養] translates the Sanskrit word pūjanā [पूजन], which means to venerate or worship.

This special Buddhist usage should not be confused with the usual meaning of kuyō [供養], which refers to a memorial service for the dead.

†So it is often represented as “oh!” or “ah!”

‡The perhaps better-known Tibetan version of this mantra is: om mani bêmê hum [ཨོཾ་མ་ཎི་པདྨེ་ཧཱུྃ].

¹⁰Kore ni te issai fujō wo kotogotoku shōmetsu-su to kanzuru-koto nari [コレニテ一切不浄ヲ悉ク消滅スト観ズル事也].

Issai fujō [一切不浄] means every trace of impurity, all that is impure.

Kotogotoku [悉く] means completely, entirely, without exception.

Shōmetsu-suru [消滅する] means (to cause something) to cease to exist; make (something) disappear.

Kanzuru-koto [観ずること] means to discover, reveal, or perceive.

¹¹Chawan ha kyaku ni taishi, iku-tabi mo ikki ni te mochiyuru-mono [茶碗ハ客ニ対シ、幾度モ一器ニテ用ユルモノ].

Chawan ha kyaku ni taishi [茶碗は客に対し] means something like the chawan goes out to the guests, or the chawan passes (back and forth) between (the host and) the guests*.

Iku-tabi mo [幾たびも] means time and again, many times.

Ikki ni te mochiiru-mono [一器にて用いるもの] means just one (chawan) is being used.

___________

*It could also mean “the chawan is used for [many] guests.”

¹²Koto ni sono kyaku i-zen ni dare no nomi-shi mo shirazu-koto [殊ニ其客已前ニ誰人ノ呑シモ不知事].

Koto ni [殊に] means especially, particularly, additionally.

I-zen ni dare no nomi-shi mo shirezu-koto [以前に誰人の呑みしも知らずこと]: i-zen ni [以前に] means just before (him), immediately before (him); dare no nomi-shi [誰人の呑みし] means who drank (from the chawan); mo shirazu-koto [も知らずこと] means something that (he) doesn't know*.

This statement seems to be saying that the guest would not know who had been served from this chawan in the past.

___________

*This could be an issue because it seems -- from the condition of some bowls that were used in the early Edo period, and then not used again since -- that the host did not always wash the chawan thoroughly after the gathering. Rather, the only cleaning it got was what was done during the temae; and after being left out to dry for several days, the bowl was returned to its box, where it remained until the next time it was needed. As a result, a film of tea (which often built up around the part of the mouth from which the guests drank) would not only remain, but become deeper and deeper every time the chawan was used.

Nevertheless, it is hard for me to generate the degree of disgust that the author of this entry seems to feel -- which strikes me as being a description of a great daimyō being afraid to sully his lips by drinking from a bowl previously used to serve a rank underling (or, even worse, a common townsman or merchant). Of course, this was an Edo period sort of sensitivity -- and, looking at the catalogs listing the temae that were taught during the early Edo period by the different schools -- particularly with reference to the kijin-date [貴人立て] class of temae (the temae used when serving a daimyō, when he is being received formally) -- as well as the kaiki that survive from that period, it seems that, more often than not, daimyō were preferentially served using a brand new chawan. So, I guess there is that “historically valid” sort of extenuation.

¹³Fukai yue, hajime ni mitsu-utsu koto ha, “RAM-VAM-[H]ŪM” no san-kaji no kanji nari [不快故、始ニ三ツ打ツ事ハ、 रँ वँ हूँ ノ三加持ノ観也].

Fukai-yue [不快ゆえ] means because this (situation of not knowing the person who drank before you) is disagreeable.

Hajime ni mitsu-utsu-koto [始めに三つ打つこと] means when (the chasen) taps (the chawan) three times at the beginning (of the temae).... This is referring to the chasen-tōshi that is performed at the beginning of the temae.

“RAM-VAM-[H]ŪM” no san-kaji no kanzuru [の三加持の観] means it seems to suggest the “RAM-VAM-[H]ŪM” triple invocation (of the Shingon ritual).

¹⁴Ato mata susugi no toki, “RAM-VAM” no ni-kaji wo motte kiyome oku-koto nari [後又スヽギノトキ、 रँ वँ ノ二加持ヲ以テキヨメ置事也].

Ato mata [後又] means “and again, later....” This is referring to the conclusion of the temae.

Susugi no toki [濯ぎの時] means when rinsing (the chasen) -- that is, during the second (concluding) chasen-tōshi.

“RAM-VAM” no ni-kaji wo motte [ रँ वँ の 二加持を以って] means with the double-invocation of “RAM-VAM”....

Kiyome oku-koto nari [清め置くことなり] means the cleaning is finished, the cleaning process has been completed.

¹⁵Shingon wo karite kono-koto wo nasu to nari [真言ヲカリテ此事ヲナストナリ].

Shingon wo karite [真言を借りて] means borrowing this (idea) from the Shingon (ritual)....

Kono-koto wo nasu [このことを成す] means (we) do (things) like this.

¹⁶(“RAM-VAM” ha hi-mizu nari) [( रँ वँ ハ火水ナリ)].

RAM [ रँ ] refers to fire, and VAM [ वँ ] refers to water -- which also agrees with Bisgard sensei’s explanations.

In Shibayama’s commentary, this last sentence is formatted as a gloss. It is not found in any of the other versions of this kaki-ire.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

各地句会報

花鳥誌 令和6年4月号

坊城俊樹選

栗林圭魚選 岡田順子選

………………………………………………………………

令和5年1月6日

零の会

坊城俊樹選 特選句

ドッグラン鼻と鼻とで交はす賀詞 荘吉

裸木のはるかを白く光る街 要

頰切るは鷹の翔つ風かもしれず 順子

人波をこぼれながらの初詣 光子

焼芋の煙たなびく志んぐうばし 和子

群衆といふ一塊の淑気歩す 順子

寒雀神馬と分かちあふ日差し 光子

寒雀入れ神苑の日のたまり 同

寒の水明治の杜のまま映す 小鳥

岡田順子選 特選句

跼り清正の井を初鏡 昌文

本殿につぶやく寒紅をつけて 光子

楪の浴ぶる日我にゆづらるる 慶月

肺胞に沁み込んでゆく淑気かな 緋路

冬草や喧騒去りて井戸残し 眞理子

馬見えぬ乗馬倶楽部の六日かな 六甲

寒鯉来おのれの色の水を分け 緋路

寒椿落つれば湧くや清正井 眞理子

寒の水明治の杜のまま映す 小鳥

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年1月6日

色鳥句会

坊城俊樹選 特選句

一束もいらぬ楪もて遊ぶ 成子

深井より羅漢に供ふ冬の水 かおり

赤なまこ横目に買ひし青なまこ 久美子

畳みたるセーターの上に置くクルス かおり

再会のドアを開けばちやんちやんこ 朝子

半泣きのやうに崩るる雪兎 成子

火を見つめ男無口に薬喰 かおり

歳晩の一灯母を照らすため 朝子

悴みて蛇となる能の女かな 睦子

その中の手話の佳人やクリスマス 孝子

悪童に悲鳴をはなつ霜柱 睦子

凍空とおんなじ色のビルに棲み かおり

かくも典雅に何某の裘 美穂

唐突に雪投げ合ひし下校の子 成子

楪や昔硝子の磨かれて かおり

奥伝の稽古御浚ひする霜夜 愛

出会ひ重ね寿限無寿限無と年惜む 美穂

冬灯一戸に遠き一戸あり 朝子

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年1月8日

武生花鳥俳句会

坊城俊樹選 特選句

流れ来し葉屑も霜を置いてをり 昭子

御慶述ぶ老いも若きも晴れやかに みす枝

初春の光りまとひし石仏 ただし

神なびの雨光り落つ氷柱かな 時江

地震の中産声高き初笑ひ ただし

歌留多とり一瞬小町宙に舞ふ みす枝

まだ誰も踏まぬ雪道新聞来 ただし

奥の間に柿餅吊し賑はへり 時江

さびしさの枯野どこまで七尾線 昭子

万象の音の鎮もり除夜の鐘 時江

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年1月9日

萩花鳥句会

初句会吾娘よりホ句のファクシミリ 祐子

書き初め震何んぞ訳あり辰に雨 健雄

吹雪突き突進するエネルギー 俊文

日本の平安祈る今朝の春 ゆかり

こがらしが枯葉ころがしからからと 恒雄

平穏な土地にて食べる七草粥 吉之

御降や茶筅ふる音釜の音 美惠子

………………………………………………………………

令和5年1月10日

立待花鳥俳句会

坊城俊樹選 特選句

被災地にすがりし木の芽盛んなる 世詩明

的中の乾いた響き弓始 誠

初場所の桟敷の席の晴れ着かな 同

初御空耶馬台国は何処にぞ 同

石段を袖振り上がる春著の子 同

細雪番傘粋に下駄姿 幸只

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年1月11日

うづら三日の月花鳥句会

坊城俊樹選 特選句

年上の夫に引かるる初詣 喜代子

地震起こり慌てふためく大旦 由季子

曇り拭き笑顔映りし初鏡 さとみ

地震の地にぢりぢり追る雪女 都

冴ゆる夜の天井の節をまじまじと 同

男衆が重き木戸引き蔵開き 同

寒月や剣となりて湾の上 同

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年1月12日

鳥取花鳥会

岡田順子選 特選句

海鳴や雪の砂丘は祈りめく 都

初電話卒寿は珠のごと笑ひ 同

針始友が未完のキルト刺す 同

授かりし神の詞や竜の玉 悦子

蜑に嫁し海山詠みて老いの春 すみ子

焚上げの火の粉加勢や冬銀河 宇太郎

古傷を思ひ出させて寒四郎 美智子

枯葦の透き間に光る水一途 佐代子

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年1月12日

風月句会

坊城俊樹選 特選句

寒の雨誦経とよもす陽子墓碑 文英

寒林を上り来よとて母の塔 千種

顔消えし元禄仏へ寒菊を 慶月

道祖神寄り添ふ寒の雨うけて 慶月

就中陽子の墓所の蕗の薹 幸風

裸婦像の背にたばしる寒の雨 同

栗林圭魚選 特選句

信州へ向かふ列車の二日かな 白陶

寒林を上り来よとて母の塔 千種

晴天の初富士を背に山降る 白陶

大寺の太き三椏花ざかり 幸風

空までも続く磴なり梅探る 久

はればれと良き顔ばかり初句会 三無

就中陽子の墓所の蕗の薹 幸風

五姉妹の炬燵の会議家処分 経彦

走らざる枯野の車両咆哮す 千種

凍蝶のポロリと落つる影哀れ れい

三椏の開花明日かと石の門 文英

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年1月13日

枡形句会(一月十三日)

栗林圭魚選 特選句

嗽ぐをどる喉越し寒の水 幸風

七福神ちらしの地図で詣でをり 多美女

七福神詣りしあとのおたのしみ 白陶

凍て鶴の青空渡る一文字 幸子

金継ぎの碗に白湯汲む女正月 美枝子

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年1月15日

なかみち句会

栗林圭魚選 特選句

曇天に寒紅梅や凜と咲く のりこ

寒梅のつぼみの枝の陽の仄か 貴薫

青空に白き寒梅なほ白く 史空

朝の日に紅色極め寒椿 廸子

我が机散らかり初めし二日かな 和魚

倒れ込む走者にやさし二日かな 三無

釦穴に梃摺る指や悴かみて あき子

夢てふ字半紙はみ出す二日かな 美貴

二日早主婦は忙しく厨事 怜

りんご飴手に兄妹日向ぼこ 秋尚

雪遊びかじかむ手の子包む母 ことこ

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年1月16日

さくら花鳥会

岡田順子選 特選句

幼子の運を担いで福引へ 実加

寒空や命尊きこと思ひ みえこ

ことわざを子が覚えをりかるた取り 裕子

元旦の母と他愛もない話 同

元旦や地震の避難を聞くことに みえこ

初詣車椅子の児絵馬見上ぐ 実加

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年1月17日

伊藤柏翠記念館句会

坊城俊樹選 特選句

古里に温石と言ふ忘れ物 雪

師の墓に愛子の墓に冬の蝶 清女

寒の月見透かされたり胸の内 眞喜栄

鴨浮寝無言の中にある絆 同

降る雪を魔物と今朝を天仰ぐ 英美子

藪入りも姑の一言行けぬまま 同

庭仕事今日冬帝の機嫌よき かづを

玻璃越に霏々と追はるる寒さかな 同

正月が地獄の底に能登地震 みす枝

雪しまき町の点滅信号機 ただし

お御籤の白き花咲く初詣 嘉和

若狭より繋がる水脤やお水取 やす香

水仙の香りて細き身の主張 同

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年1月17日

福井花鳥句会

坊城俊樹選 特選句

寒紅の濃き唇が囁きし 世詩明

お雑煮の丸と四角と三角と 同

正月の馳走其々ある謂れ 千加江

新年の風も言の葉も美しく 和子

磯の香も菰巻きにして野水仙 泰俊

捨て舟を取り巻くやうに初氷 同

左義長や炎崩れて闇深し 同

去年今年形見の時計よく動く 同

ふと今も其の時のマフラーの色 雪

天地に誰憚からぬ寝正月 同

迷惑を承知の猫に御慶かな 同

不器用も父似の一つ初鏡 同

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年1月17日

鯖江花鳥句会(一月十七日)

坊城俊樹選 特選句

而して九十三の初鏡 雪

蛇穴に入り人の世は姦しく 同

紅を差し眉ととのへて近松忌 同

懐手おばあちやん子を憚らず 同

鬼つ子と云はれて老いて近松忌 同

着膨れて顔ちさき女どち 一涓

歌かるた子の得て手札取らずおく 昭子

年新たとは若き日の言葉とも やす香

新年を地震に人生うばはれし 同

元旦を震はせる能登竜頭めく 同

裂帛の気合を入れて寒みそぎ みす枝

風の神火の神乱舞どんど焼き ただし

八代亜紀聞きをり外は虎落笛 清女

寒怒濤東尋坊に砕け散り 同

波の腹見せて越前浪の華 世詩明

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年1月19日

さきたま花鳥句会

月冴えて城址うろつく武者の翳 月惑

仲見世を出て蝋梅の香に佇てり 八草

枯菊や木乃伊の群の青き影 裕章

寒鴉千木の反り立つ一の宮 紀花

合掌す金波銀波の初日の出 孝江

青空に白き一機や寒紅梅 ふゆ子

初詣令和生まれの児と犬と ふじ穂

白鼻緒水仙の庫裏にそろへあり 康子

激震の恐れ記すや初日記 恵美子

お焚き上げ煙を浴びて厄払ひ 彩香

我が干支の年につくづく初鏡 みのり

家篭りしてをり冬芽萌えてをり 良江

………………………………………………………………

令和5年12月1月

花鳥さざれ会

坊城俊樹選 特選句

師を越ゆる齢授かり初鏡 雪

初笑玉の如くに美しく 同

大晦の右大臣左大臣 同

猫の名は玉と答へて初笑 同

天が下縁深めゆく去年今年 数幸

能登の海揺るがし今日の空冴ゆる 和子

しろがねの波砕かれて冴え返り 笑子

語り継ぐ越前の秘話水仙花 同

雪降れば雪に従ふ越暮し 希子

皺の手にマニキュア今日は初句会 清女

初電話親子の黙を解きくれし 同

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年11月

花鳥さざれ会

坊城俊樹選 特選句

蟷螂を見て戻りたるだけのこと 雪

もて余す老に夜長と云ふ一つ 同

蟷螂の緑失せつゝ枯れんとす 同

小春日や袱紗の色は紫に 泰俊

正座して釜音聞くや十三夜 同

海沿ひにギターの調べ文化の日 千加江

枝折戸をぬけて紅さす返り花 笑子

祇王寺の悲恋の竹林小鳥来る 同

大胆な構図を取りし大銀杏 和子

宿の灯も消して無月の湖明り 匠

秋の海消えゆくものにますほ貝 天空

落葉降る賽の河原に降る如く 同

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

令和5年12月

花鳥さざれ会

坊城俊樹選 特選句

異ならず枯蟷螂も人老ゆも 雪

世の隅に蟷螂は枯れ人は老い 同

無造作に残菊と言ふ束ね様 同

冬ざれや汽車に乗る人何を見る 泰俊

石膏でかたまりし腕冬ざるる 和子

山眠る小動物も夢を見る 啓子

路地裏の染みたる暖簾おでん酒 笑子

冬ざれや路面電車の軋む音 希子

おでん屋の客の戯れ言聞き流し 同

風を背に連れておでんの客となり かづを

にこにこと聞き役おでん屋の女将 同

冬紅葉地に華やぎを移したり 同

街師走見えざるものに背を押され 同

(順不同特選句のみ掲載)

………………………………………………………………

1 note

·

View note

Text

SADŌ -L’ANTICA CERIMONIA DEL TÈ GIAPPONESE

La cerimonia del tè giapponese, tradizionalmente chiamata Sadō (茶道, "via del tè"), interessa e confonde le persone che la vedono per la prima volta.

Tanti utensili, numerosi steps e profondi significati che si celano dietro ogni passaggio.

Infatti, quando parliamo di Sadō, non intendiamo il semplice gesto di bere il tè, ma si tratta di un vero e proprio rituale, tanto affascinante quanto complesso.

IL TÈ MATCHA CERIMONIALE.

Il Sadō, è una pratica che vede come protagonista il tè verde giapponese per eccellenza, il Matcha. La pratica è utilizzata per instaurare una relazione positiva tra gli ospiti, in cui viene celebrata la bellezza della semplicità, la spiritualità e soprattutto si riflette sull’importanza dei rituali quotidiani per una vita serena e armoniosa.

LA SALA DA TÈ, SEMPLICITÀ E ARMONIA.

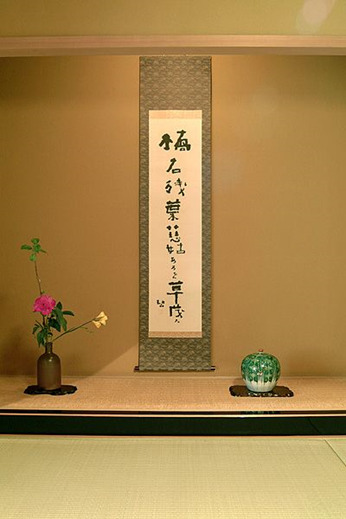

Quando entrerai in una sala da tè, probabilmente durante un viaggio in Giappone, rimarrai stupito da quanto essa sia semplice e molto poco arredata. Oltre agli utensili per preparare il tè già in posizione e pronti per essere utilizzati, noterai solamente una pergamena con una poesia e una decorazione floreale.

La poesia e i fiori, hanno un significato molto profondo nella cerimonia del tè. La Poesia è spesso scelta dall’oste e aiuta a dare un tono particolare all’evento, mentre i fiori vi permetteranno di entrare in armonia con la natura e avvicinarvi ad essa, creando un’atmosfera di tranquillità e riflessione.

GLI UTENSILI.

Gli oggetti per la cerimonia del tè in una casa tradizionale giapponese possono essere numerosi se li includiamo tutti. Diamo invece un’occhiata a quelli fondamentali e indispensabili per la preparazione del tè Matcha cerimoniale:

NATSUME (棗): È il contenitore laccato, usato per conservare e proteggere la polvere del tè dall’umidità. Non è considerato come un semplice recipiente, ma è un vero e proprio prodotto artigianale che contribuisce decisamente all’estetica dell’evento.

CHASEN(茶筅): È l’utensile migliore quando si deve preparare il tè Matcha. Serve per mischiare adeguatamente la polvere da tè all’acqua calda. Viene ricavato da un solo pezzo di bamboo poi “sfilacciato” per dargli la sua forma caratteristica, permettendogli di spiccare tra tutti gli altri oggetti in termini di peculiarità.

CHASHAKU (茶杓): È un sottile cucchiaio di bamboo, intagliato appositamente per poter prelevare dal Natsume, la giusta quantità di polvere Matcha. La sua forma tipica prevede la punta curvata.

È molto importante che utensili come questo, che entrano in contatto diretto con la polvere Matcha siano di materiali naturali come il bamboo e non di metallo o acciaio.

CHAWAN (茶碗): È il tipo di ciotola tradizionale scelta per la tradizionale cerimonia del tè. Fatta in ceramica, essa presenta un’iconica forma cilindrica che permette a chi prepara il tè, di poter muovere in piena libertà il Chasen.

Durante la cerimonia, gli ospiti devono mostrare apprezzamento e rispetto per l’artigianato che si cela al loro interno in quanto delle vere e proprie opere d’arte.

Scopri i nostri prodotti per fare anche tu la cerimonia del tè e stupire i tuoi ospiti! Visita il nostro Shop www.zanzino.it

1 note

·

View note

Photo

A delicate blend of Okumidori and Samidori, our Kiku-no-Sono matcha exemplifies the elegance and balance of Uji matcha 🍵 . . . . . #matcharitual #matchamoment #matchamadness #matchalife #matchamornings #matchalover #matchatime #matchalovers #teatime #matchaaddict #matchatea #matchaholic #matchameditation #matchagreentea #matchabowl #teabowl #matchawhisk #kohiki #chawan #濃茶 #茶碗 #粉引 #抹茶 #茶筅 #日本茶 #宇治茶 — view on Instagram https://ift.tt/GNAFWSb

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Young Lords’ Coming of Age

元亀3年春頃、信長の子達が岐阜城で元服した。嫡男の奇妙丸は秋田城介信忠と号し16歳である。次男茶筅丸は北畠三介信雄と号し15歳である。三男三七丸は神戸三七信孝と号し15歳である。子供たちの成長により、いよいよ、信長の武威は強大になり、人々はこれを羨んだと言う。

In the spring of the 3rd year of the Genki era (1572), Nobunaga's sons came to Gifu Castle to hold their genpuku (coming of age ceremony). The eldest son, Kimyoumaru, was named Akita-jou-no-suke Nobutada, and he was 16 years old. The second son Chasenmaru was named Kitabatake Sansuke Nobukatsu, and he was 15 years old. His third son Sanshichimaru was named Kanbe Sanshichi Nobutaka, and he was 15 years old. With his children now matured, Nobunaga's military might also grew, to the envy of the people.

(Seishuu Gunki, vol 6)

秋田城介 Akita-jou no Suke is a title traditionally granted to the ruler of the northern area of Dewa province, with Akita Castle being the lord’s residence. As with many other Sengoku era titles, this is only a signifier of a high status, and Nobutada does not actually have any land/territory in Dewa.

The Shinchoukouki says that Nobutada was actually only granted this title in 1575, with his original genpuku name being “Nobushige”.

Nobukatsu’s original genpuku name purportedly was Kitabatake Tomotoyo 北畠具豊.

When he received the “Sansuke” title is something I’m not entirely sure of. 三介 Sansuke means that the person holds the title of “suke” (deputy-governor) of Hitachi, Kazusa, and Kouzuke provinces. These provinces were traditionally “governed” by imperial princes, and samurai are only allowed to have the title of suke of these provinces (as opposed to the governor title, 守 kami, e.g Kazusa no Suke and not Kazusa no Kami). As with Nobutada’s, this is also a meaningless title.

Nobukatsu being called 三介 is not proof that he was actually born third (this is a theory that I’ve seen floating around online). I’ve not actually seen a text where he was being referred to by Sansuke yet. This is one example where he is referred to as Sansuke in documentation. The Shinchoukouki refers to Nobukatsu by “Kitabatake no Chuujou”. Either way, as Sansuke refers to “three provinces”, it has nothing to do with order of birth.

Nobutaka apparently has no special titles that he went by, and was simply called “Sanshichi Nobutaka” in various texts. I did see a theory that his childhood name was never Sanshichimaru. Sanshichi was actually short for Sanshichirou, a “middle name/alias“ commonly awarded during genpuku (for example, Nobunaga’s was Saburou), and his childhood name is actually unknown.

It’s rather common for texts to claim or confuse “alias” names with childhood names. For example, Sanada Nobuyuki’s alias was Genzaburou, and Wikipedia used to claim that this was his childhood name.

#oda nobutada#oda nobukatsu#oda nobutaka#oda clan#oda family#sengoku#Sengoku period#Sengoku Era#Warring states#Warring States Period#Warring States Era#japanese history

9 notes

·

View notes