#Felice Peppone

Text

#Mafia IV#Mafia 4#Mafia Trilogy#Ennio Salieri#Marcu Morello#Felice Peppone#Leo Galante#Sal Marcano#Lou Marcano#Valerio Marcano#Lucio Marcano#Sammy Robinson

0 notes

Text

Storie ed emozioni della domenica.

Dal Grande Spirito allo Spirito Santo.

Tatanka, taverna del pellegrino, oasi di pace. 📷

Ancora ateo ma molto provato dagli eventi. Non mi ero ancora convertito, e stavo attraversando il periodo più duro della mia vita. Ma nonostante tutto avevo dei punti fermi su cui appoggiarmi e molti amici che mi sostenevano, conoscendo le cause delle mie sofferenze. Subivo ingiustizie da parte di chi invece, avrebbe dovuto aiutarmi. Le cause? Avevo acquistato un luogo che non avrei dovuto prendere io, già, faceva gola ai qualcuno dei potenti che amministravano il Comune e ad altri che in teoria avrebbero dovuto stare neutri.

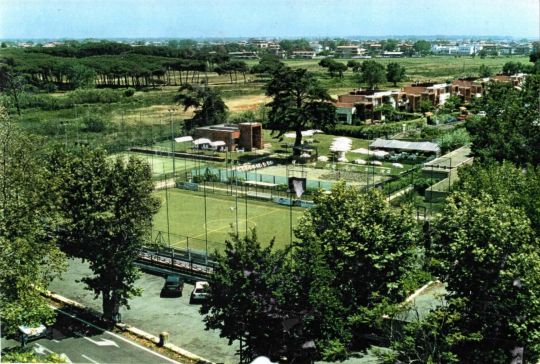

Era ridotto cosi quando l'ho acquistato io ma era al centro del paese e in più confinava con quella che si può ben vedere, un'antica chiesa del 1700 circa, ancora diroccata e sconsacrata. Divieti su divieti, ma nonostante aver dovuto rinunciare a molte delle strutture che avevo nei programmi come per esempio una piscina, alla fine questo è stato il prodotto che sono riuscito ad ultimare. Avevo due squadre in serie "A" sia maschile che femminile e i campi di calcetto erano necessari.

Non mi fecero muovere più di cosi e non potetti più avere nessun altro permesso, nel frattempo avevano ristrutturato e riconsacrata la chiesa. E cosi, come funzionava anticamente, mi ritrovai contro Sindaco e Comune, Chiesa, clero e Belle Arti con il naturale coinvolgimento dell'arma dei carabinieri. Sindaco comunista (Peppone) prete (Don Camillo)...si voglio finire questo post con il sorriso sulle labbra pensando che è solo passato e che seppure in venticinque anni di soprusi che in Italia conosciamo bene, forse proprio per tali sofferenze, io là ci ho incontrato, e conosciuto e ricevuto il Signore nel mio cuore e nella mia vita.

Nello stesso periodo dunque, iniziò la mia storia come pellegrino e mi ritrovai come d'incanto ad essere un uomo davvero felice. Avevo con me il Fratello e l'Amico come Guida, e tutte le Vie del mondo da percorrere in libertà. La vera Libertà!

lan ✍️🗝

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

New story! A little Don Camillo one-shot, set (roughly) between 1951 and 1957, my first foray into canon time for these guys. Hope you like!

Summary: Both Don Camillo and Peppone have a bone to pick with a trumpet player. Music has charms to soothe the savage beast, but what about the priest and the mayor? (on FFnet/on AO3)

THE TRUMPET OF CONTENTION

In the Lowlands, music, like a few other subjects, is something to be treated seriously.

Giuseppe Verdi is, of course, rightfully revered, and his name and works are one of the very few things that can make everyone – be they Red, Green, White, or Black – reach an agreement. It’s not even a matter of having culture or education: people pulled out of school as kids still know their Nabucco from their Trovatore. Folks will come by the music gene through blood, and you’ll find entire families passing down names like Radamès, Ofelia, Ernani, or Desdemona.

The Pedrettis were such a family. Iago Pedretti had a good voice for bel canto, his son Corrado played the bass drum, and when his daughter Leonora started to show interest for the trumpet, the little girl quite naturally found a place in the town band. She was singularly gifted, and before she was twelve years old, she could be found playing among the more experienced musicians on days of important events, wearing proudly her own bright white shirt and a cap that looked a little too big for her head.

The Pedrettis were so proud that, every time the band played, the whole family – grandfathers and grandmothers, aunts, uncles and cousins – went out en masse, all wearing their Sunday best, to see Leonora and her trumpet. They turned up for everything: town festivals, religious processions, political events, and so on and so forth. When Peppone was first re-elected as mayor, the band followed him and his staff on foot from the Communist headquarters to the town hall; as they crossed the main square, only a dozen metres from the church doors, the Pedrettis were first in line to applaud, even though every single one of them was a staunch anti-Communist and the band played Bandiera Rossa and L’internationale.

Don Camillo had watched the proceedings from the rectory door with his arms crossed, jaws clamped on his half-cigar, glowering at the blatant provocation. Afterwards, he went to the Pedrettis and protested to the paterfamilias.

“How can you let that little girl play for the Communists? Festivals and processions are fine, but not this Bolshevik propaganda!”

Pedretti was unperturbed.

“Reverend, musical talent is apolitical. As long as my little girl plays well, she can play whatever she likes within the limits of the law.”

Don Camillo bit his lip and left it at that. The day after he went to see Peppone in his workshop.

“Listen,” he said with a stormy glare, “the band aren’t half bad even though half of them are lunatics who still think Stalin is a decent person for some reason; they can parade in front of the church playing their nonsense as much as they like if they don’t mind having their bottoms kicked from here to Moscow if I catch them. But that little Leonora Pedretti is an innocent and I won’t let you recruit children for your Party.”

Peppone looked up from the motor he was working on and met Don Camillo’s eyes with a scowl of his own.

“I’m not recruiting anyone from the band. That kid is good with a trumpet, that’s it. Nobody’s making her wave a red flag around.”

“You’re right. She just plays the red flag song. Next time I’ll need music I’ll just hire the band from Molinetto. I hear they only play for funerals and processions.”

Peppone exploded. “Even you wouldn’t dare to do something so vile as that!” he shouted. “Just because you’re miffed I got re-elected –”

“Why on Earth this town picked you again knowing what you’re capable of is beyond me,” said Don Camillo huffily – especially as himself had, in what he considered a moment of weakness, voted for Peppone. “But no, your election in itself has nothing to do with it. The problem is that you and your henchmen are making a thirteen year old lass play music that could get her excommunicated, with her none the wiser!”

“If the Pope wants to set the Spanish Inquisition on people for playing music, that’s your problem, not mine! And I’m not the conductor, that’s old Gianelli’s job!”

“It’s the official town band! As the mayor and the boss of the region’s Communists, I’d say it’s your problem!”

They were nose to nose, sleeves rolled up, glaring daggers, and God only knows what would have happened if the sound of a lone trumpet, soon followed by a few other instruments, hadn’t reached them at that very moment.

It was rehearsal time for the town band and all windows were wide open to the cool evening air. Both men recognised the solemn tones of “Un dì, felice, eterea” from Il Trovatore. It worked surprisingly well, even without voices.

“Verdi will always be Verdi,” remarked Peppone quietly after a while.

“Yes he will,” said Don Camillo who had a lump in his throat.

They exchanged sheepish glances, feeling rather ridiculous now that the heat had died down. Then Don Camillo remembered exactly what had got him so worked up; but he shook his head.

“Look,” he said, “hear me out. We both know that the child has talent and Gianelli will soon be out of his depth because he only knows the basics of trumpet playing. She’ll need to study music seriously, in the city.”

Peppone nodded gravely. “I agree. Problem is, I know the Pedrettis. They’re poor as church mice. They couldn’t pay for music school even if they worked every second of every day for a hundred years.”

They stared at each other while the music drifted in on the breeze. Peppone put down the wrench he had been clutching and scratched the back of his head.

“I can have a whip-round around town,” he said eventually. “The Pedrettis aren’t very popular with my lads, but this is about making sure that a child of the people gets a decent education and a future. And we’ve all heard her play Verdi. Imagine what she’ll be capable of with a proper teacher!”

“I’ll convince the landowners to chip in,” said Don Camillo. “It won’t be easy, but I’ll wager they’ll listen to their parish priest. Besides, I can just point out the fact that she’d no longer have to play that garbage of yours.”

Peppone clenched his fists. But he breathed deeply and held out his hand.

“All right. Let’s see if the two highest authorities in the village can’t make this work,” he grumbled.

In the distance, the band struck up another song, faster and more spirited. Don Camillo shook Peppone’s hand heartily and walked away with a beaming smile while Peppone went back to his motor, humming along absently as he worked.

So it was that the town band lost a trumpet player, and little Leonora Pedretti went to the city to study music. An older cousin put her up; she paid for room and board by doing small odd jobs and delivering packages, and worked hard on both music theory and practice.

Leonora was not the first local child the village had helped on the way to higher spheres; it was rare, but not unheard of. The entire town contributed to the school fees: tenant farmers who barely had ten lire to rub together, die-hard Communist workers who called the Pedrettis ‘reactionaries’ and all kinds of unpleasant things, and even the rich farmers who found it easier to part with one of their limbs rather than money.

Such is the power of music. Politics often work their way through people’s heads; music always works through their hearts.

Years passed, bringing hot summers, hard winters, and one disastrous flood when heavy rains made the great river break its banks; people mostly waited till their houses were clean and dry before tearing each other apart over politics again. Elections came and went along with the years, and Peppone was re-elected mayor once more.

Through all that, the town folk cherished one of the real apolitical constants: the knowledge that their little trumpet player in training was doing a good job. The cousin she lived with wrote regular letters to her parents with news and the progress she made, until one day Leonora sent her own letters, because she had found a place she could live in by herself.

The few people who had the occasion to go to the city and hear her play all came back with reassuring words: the girl was good. Seeing her in the brass section in such deep concentration that she sometimes went cross-eyed justified all expenses and sacrifices. Her trumpet blended in perfectly with the rest of the orchestra, not a single note out of tune, which is the thankless fate of musicians without solos: to be essential, but easily overlooked threads in the big tapestry of orchestral music.

And then one day, as they combed through Leonora’s newest letter, Pedretti and his wife found a word that made them peer at the paper as though with a microscope. A word that was incongruous, fantastic, and truly and utterly foreign.

Jazz.

Their little girl wrote about learning to play jazz music.

The word was far from unfamiliar, of course. People listened to the radio, which often enough did feature music not composed by the classical masters. But in these parts, where land had history written in the blood of generations of farmers who lived and died on it not so differently than their parents had, and where the great river stretched out in the sun and in the mists, carrying hundreds of years of dreams, tears, and laughter with its mud and its pebbles, novelty and any of its potential contribution had to be weighed and studied before being allowed to become familiar.

Jazz was considered music, of course, but not ‘serious’ music. It was good enough for city people or foreigners – in other words, people who lived further along the country road – but not hard-working people who rose with the sun to feed the pigs, tilled the earth, or worked dairies, and then went to bed with their bones aching more every night.

The Pedrettis kept the letter and didn’t breathe a word to anyone, but soon enough, the word got out and ran throughout the village and its seven frazioni like an overexcited puppy. Unfortunately for the Pedrettis, it turned out that a lot of people had a lot to say on the subject, and much of what they had to say concerned young Leonora and the supposed lack of moral fibre in her upbringing. Nobody could agree on which would have been worse: the fact that a good, decent country girl, whom they’d known since she was little and who had received a proper Christian education had abandoned Verdi for the sirens of foreign music – or if that same girl had dyed her hair and gone around wearing make-up and short skirts.

Those whose opinion on the matter ranged from asking how bad it all could be anyway and not caring one bit what a person did as long as they were happy were sadly few and quickly drowned in the mass of gossip.

Chatter grew and grew until Leonora came back to her parents’ for a few days of holiday.

She had grown from a skinny child into a long, sprightly girl who walked with calm certainty and didn’t talk much. Her hair was intact, a little longer than it had been, and she wore no make-up at all. The folks who were still unsure about which of jazz or make-up was worse quickly made up their minds and decided on the former.

Leonora mostly stayed at the family farm for the first couple of days and to all intents and purposes remained blessedly unaware that she and her trumpet were all the village could talk about these days.

Since it was one of the few subjects which transcended politics, the more vehement critics soon referred to their own moral authority: the reactionaries and the little old ladies complained to Don Camillo, the Communists to Peppone in his capacity as the section’s secretary, and the others to Giuseppe Bottazzi in his capacity as mayor – which meant Peppone pulled a double shift. He was mightily annoyed about it all.

On one hand, it irritated him to no end that imperialist America had ruined yet another honest Italian girl, luring her with its newfangled ways and flashy… what exactly he hadn’t figured out yet, but knew he would have to if asked. And he couldn’t swallow the fact that a musician, after studying and playing masters like Verdi or Puccini – but mostly Verdi – could just move on to something so different as simply as that. It felt like a betrayal.

On the other, he had always had an argumentative streak, and seeing all those people finding fault in one girl bothered him a little. Leonora Pedretti wasn’t a political adversary and she hadn’t chosen to shoulder any kind of authority at all: she was only a trumpet player. And not even the kind to want to play Giovinezza or La Marcia Reale, either.

It was all very complicated, and Peppone didn’t like complicated.

In the end, he shoved his hat on his head one morning and went out to town.

It was market day on a fair, bright morning, and people flooded the main square. Peppone pushed through the crowd and the stands to get to the church parvis, where Don Camillo was sitting on his usual bench near the rectory door, reading a newspaper and smoking a half-cigar.

“Listen here,” he said, planting his fists on his hips, “what have you been telling your church biddies about that Pedretti girl?”

Don Camillo raised his head, looking curious.

“What do you mean?”

“There’s been no end of whiners and complainers knocking on the People’s House and the town hall lately telling me I should do something about that blasted affair. The Communists I can handle, but some of the others were your crowd and I’ve had it up to here.”

“Comrade, you’ve chosen to run for mayor and somehow you got elected,” said Don Camillo, going back to his newspaper. “It’s only natural that people will look to you to sort things out, God help them.”

Peppone was beginning to see red.

“When the girl was in the town band, she played the people’s music and you couldn’t stomach it. Now she’s not in the town band anymore and she’s playing American propaganda garbage! How do you like that?”

Don Camillo folded up his newspaper and rose to his feet.

“And what’s it got to do with me?” he asked in a dangerous voice.

“You’re the one always defending ruddy America like it’s a bastion of decency against the big scary Reds,” shouted Peppone, “and meanwhile the same America turns our girls’ heads and corrupts them until they forsake Verdi for some so-called music nobody can understand unless they speak English!”

“Reds never scare me, big or little!” bellowed Don Camillo, and he gripped Peppone by the lapels of his jacket.

Peppone grabbed him by the front of his cassock and roared, “I’ll see about that!”

Blood boiled, the pressure was off the charts, and blows would probably have started raining any second from two pairs of hands as big as shovels, when a loud, discordant noise sounded all around the square.

It was a noise like a duck getting stomped on, and it was just absurd enough to make both men freeze.

The market stand owners and the people around them had left their shopping to watch something potentially more interesting, namely a brawl between the mayor and the priest; but they all froze, too, and turned to the point of origin of that awful sound.

Young Leonora Pedretti was standing in the middle of the square wearing her Sunday dress and a defiant scowl on her face. In her right hand was her trumpet.

She breathed deeply, raised the mouthpiece to her lips, and began to play.

Later on, when people could reflect on it calmly, they realised things were missing, like a clarinet, a piano, some percussions, and maybe a double bass. But it was of little importance.

Music rose out of that little trumpet, a melancholic melody, like someone determined to keep hope alive through tears. The music – thin, bordering on reedy – trembled and tensed but always landed on its feet. It was a sound that tore a piece of your heart while telling you you were allowed to cry over it. Then Leonora segued into another song, more cheerful, cheeky even, with little high notes that sounded like winks, if winks could be turned into sound. It wasn’t mocking, however, but rather invited you to share a joke. The number was short, and soon gave way to a third song.

This time the trumpet was gentle and warm, the notes ample and clear, and the melody flew into the blue sky to the great river shining under the sun. And the people on the square heard, in the silence between breaths and in the quiver that punctuated the notes, the voices of men, women and children not so different than they were, who played and sang about hope, freedom, loss, joy, grief, their faith in God and their own great river that flowed majestically to the sea, carrying hundreds of years of blood, tears, and dreams not so different than their own.

Leonora held the last note and slowly lowered the trumpet, her face crimson from neck to hairline. She cast a last long look at the square full of people and walked away without a word. Everything she meant to say had been said.

Peppone and Don Camillo had loosened their grip on each other during the impromptu concert without quite knowing when or how. They both kept staring at the spot Leonora had been half a minute after she left.

“…Well,” said Don Camillo eventually in a voice that shook ever so slightly, “that wasn’t Verdi.”

“No, it wasn’t.” Peppone ran a hand across his eyes and fumbled for his handkerchief.

They looked at each other, opened their mouths to add something, but both realised at the same time that they, too, had said everything they meant to say.

They both took off their hats to each other. Don Camillo returned to his bench, still looking dazed, while Peppone went back home the long way, along the road on the main dyke, where he could see his great river and watch the sun wink on the muddy waters.

After that memorable market day, when Don Camillo received a complaint about girls who were no better than they should be and played music they should not, he threw out his arms and said, “I don’t know if it’s the Devil’s music. All I know is what I heard, and what I heard was so beautiful that I don’t believe God would leave it to the Devil.” And the crucified Christ on the main altar smiled, because he was right.

When the same people went to Peppone, he crashed his enormous fist on his desk and shouted, “The next wretch who says anything against that bloody trumpet goes through the window and learns to fly. Do I make myself clear?”

“Daddy,” his youngest boy asked him that very evening as his father went to give him his good night kiss, “what did that lady play the other day, exactly?”

Peppone vaguely sensed that the question had some importance; he thought long and hard before answering in a tone of finality, “She played the trumpet, and she played it well.”

“That’s it?”

“That’s it.”

And, as it turned out, he was quite right.

THE END

Thank goodness for music. The world would be so much darker, colder, and poorer without it!

Translations/Notes:

Red, Green, White, and Black: respectively Communists, Republicans (anti-monarchist, anti-clerical, and anti-fascist party, which was still left of the political centre at the time), Christian Democrats, and Fascists.

Radamès is from Aida; Ernani is from the eponymous opera; Desdemona and Iago are from Otello; Corrado is from Il Corsaro; Leonora is from Il Trovatore and La forza del destino; Ofelia stands out, being from a lesser-known opera (based on Hamlet) and not from Verdi.

Don Camillo voting for Peppone in his first re-run as mayor is a reference to one of the short stories, "Ancora il fantasma del cappello verde" (the ghost with the green hat again). The "ghost" is Peppone, who sneaked into the church in the middle of the night to pray for re-election and inadvertently left his hat behind. At the very end of the campaign, when it looks like he's going to lose, he makes an honest speech, straight from the heart, in which he asks his citizens to treat the election as a verdict on how good a job he did… and wins by a landslide. Don Camillo later admits to the crucified Christ on the main altar that seeing Peppone like this, sad and lonely, moved him so much he voted for him – and he's confused and furious about it.

I must admit fumbled with the chronology a little bit. Peppone's first re-election was in summer 1951, and the terrible flood from the Po river (some of it depicted in the second Don Camillo film with actual news footage) happened in both the real world and the "Little World" a few months later, in November.

Giovinezza (Youth) was the official hymn of the Italian Fascist Party, regime, and army up until 1943; the Marcia Reale (Royal March) was the official hymn of the Kingdom of Italy from 1861 to 1946. Both were usually played with the other, and both were forbidden after World War 2.

(If you liked, please consider leaving a comment so I know I’m not just shouting in the desert - not that I mind, but it gets lonely without someone to share it with!)

10 notes

·

View notes