#Robert Solow

Text

Robert Solow

Robert Solow died in December 2024. Here is one article about his life and career.

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

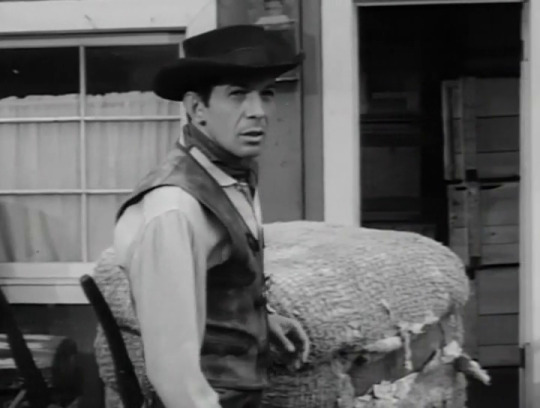

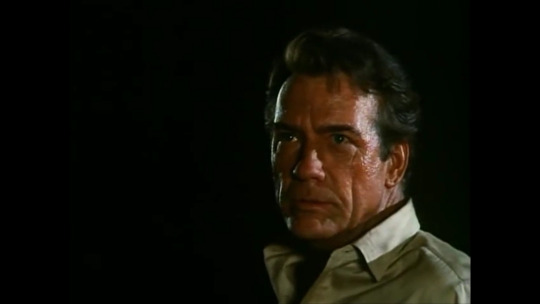

Today in the Department of Before They Were Star Trek Stars, Leonard Nimoy guest stars in "Run, Killer, Run," episode 17 of the single season of A Man Called Shenandoah (original air date January 10, 1966).

Nimoy plays a world-weary hired killer who's engaged to bump off the main character while he's working on the docks in Galveston. He comes to like him, and even helps him in a brawl with a longshoreman, but that doesn't stop him from trying to do what he's been paid to do.

A Man Called Shenandoah is a weird, interesting little show, and I highly recommend watching if you can get your hands on it. A man wakes up in a frontier town with a head injury and a case of amnesia. Assuming the name "Shenandoah," he spends 34 half-hour episodes roaming the Old West, looking for clues to his real identity. The really interesting part is the growing suspicion that he wouldn't like the man he used to be, and might be better off in the long run by not remembering.

Other Trek connections:

Herbert F. Solow, executive in charge of production for The Original Series, and Lindsley Parsons, Jr., executive in charge of production for Star Trek: The Motion Picture, were both uncredited members of the MGM Television production team for A Man Called Shenandoah.

Sally Kellerman, who played Dr. Elizabeth Dehner in "Where No Man Has Gone Before," plays a ship owner's daughter in love with the main character.

Bonus: Check this out!

#star trek#star trek tos#star trek the original series#star trek the motion picture#a man called shenandoah#1960s tv#tv sci fi#tv westerns#leonard nimoy#sally kellerman#robert horton#herbert f solow#lindsley parsons jr

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you are a STAR TREK fan and need an antidote to Gene Roddenberry's self-mythologizing about his and the franchise's (alleged) progressive idealism, I recommend the following:

Read INSIDE STAR TREK: THE REAL STORY by Herb Solow and Robert Justman. Solow and Justman were there (Solow was the Desilu head of production and Justman an associate producer on TOS), and they puncture a lot of Roddenberry's myth-making very effectively. One side effect: Hearing Alexander Courage's STAR TREK theme will start to make you mad once you learn of Roddenberry's sleazy trick to pocket half of Courage's royalties.

Watch PRETTY MAIDS ALL IN A ROW, a 1971 satire/exploitation film/black comedy directed by Roger Vadim and written and produced by Roddenberry (based on a now-obscure 1968 Francis Pollini novel), with a couple of STAR TREK veterans (including William Campbell and James Doohan) in the supporting cast. The movie, which stars Rock Hudson as a former football star turned guidance counselor who uses his position to sleep with and then murder high school girls, is characterized by precisely the same brand of leering-creep sexism as Roddenberry's STAR TREK efforts, here stripped of any veneer of high-minded speechifying. It's not a good movie (it scores a few satiric points here and there, but it's SO sleazy you'll need a shower afterward), but it is instructive in this regard.

Try to come to grips with the fact that before getting into TV, Roddenberry was a speechwriter for William H. Parker, chief of the legendarily racist Los Angeles Police Department, a fact that puts STAR TREK's sometimes very uneasy combination of high-minded rhetoric and liberal imperialism in some perspective. Herb Solow remarked that "it seemed odd that a man as politically and socially liberal as I already knew Gene to be would be so trusted by Chief 'Bill' Parker, well-known in Los Angeles for his ultra-conservative views."

#star trek#teevee#gene roddenberry#pretty maids all in a row#roger vadim#herbert f solow#robert h justman#inside star trek#star trek tos

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Killdozer (1974)

My rating: 4/10

Turns out a bulldozer is way too slow and ponderous to make an effective monster. Who knew?

#Killdozer#Jerry London#Theodore Sturgeon#Ed MacKillop#Herbert F. Solow#Clint Walker#Robert Urich#Carl Betz#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

From student to faculty member, in one folder: What the “Really Old Stuff” reveals about Gary Becker’s early studies and career

Projects Archivist, Weckea Lilly, reflects on the implications of a single folder found while processing the papers of economist and Nobel Prize winner, Gary Becker.

One slightly overstuffed folder in the Becker papers labeled “Really Old Stuff” was extracted from the collection for closer inspection during processing activities last week. Opening the folder and examining its contents, I discovered a series of equations (theorems) and proofs, course notes, a section of an article ripped from an academic journal, short theoretical or response papers, charts and tables, data sheets, correspondence written to Milton Freeman (from Robert Solow, another from someone at the National Bureau of Economic Research, and someone named Phil), and a partial autobiographical sketch.

The material is dated from 1951 to 1955 which include the culminating years of Becker’s graduation from Princeton University with a bachelors in mathematics and the year he finished doctoral studies at the University of Chicago in economics. The inscriptions and penmanship here are that of a seemingly younger, eager scholar (compared to the handwritten documents in other portions of the collection, dated much later in his career).

Much of the work contained here is, by and large, Becker’s toil in mathematical economics. It seems that he was already interested in and influenced by the ideas that analyses in economics could be applied to everyday issues and concerns. This folder also reflects his time with Milton Friedman. In Becker’s essay on Milton Friedman, he wrote, “I had taken several graduate courses in economics and mathematics while an undergraduate at Princeton, and I was preparing two articles for publication when I entered Chicago.” An early version of one of those papers is housed in this folder under the title “On the classical monetary and interest theory.”

Becker also wrote, “When I became an assistant professor in the department in 1954, I spent half my time assisting Friedman in running the [Money and Banking] Workshop. So I was closely involved with it during the early days.” Working so closely together there must have resulted in some mixing and sharing of files and communications that may not have been returned to its original owner.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Robert Solow has passed away. He was a towering and unique figure in the field of economics, and his economics was sarcastic and witty too, especially towards his neoliberal colleagues:

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

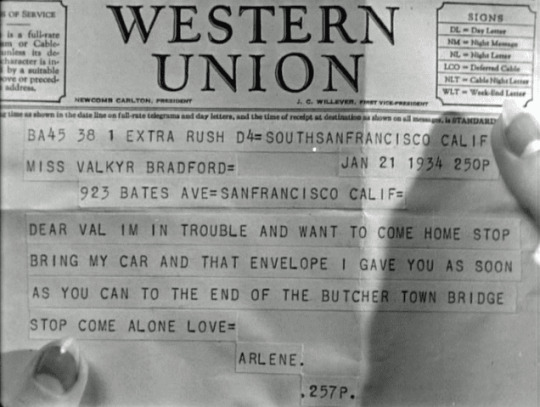

Fog Over Frisco (William Dieterle, 1934)

Cast: Bette Davis, Donald Woods, Margaret Lindsay, Lyle Talbot, Hugh Herbert, Arthur Byron, Robert Barrat, Henry O'Neill, Irving Pichel, Douglas Dumbrille, Alan Hale, Gordon Westcott. Screenplay: Robert N. Lee, Eugene Solow, based on a story by George Dyer. Cinematography: Tony Gaudio. Art direction: Jack Okey. Film editing: Harold McLernon. Music: Bernhard Kaun.

San Franciscans don't call it Frisco anymore but they do call the fog Karl. Not that fog has a lot to do with the story of Fog Over Frisco, which is mostly a fast-paced murder mystery involving a socially prominent family and some stolen securities. Although Bette Davis is nominally the star, she's the murder victim and disappears from the film halfway through. Her prominent billing probably has to do with the realization at Warner Bros. that she was becoming a big star: This is also the year of Of Human Bondage, the John Cromwell film that Davis made on loanout to RKO. Although Margaret Lindsay, who plays Davis's stepsister, has the larger part, and the cast is full of watchable character actors like Hugh Herbert, Alan Hale, and (in a small part) William Demarest, Davis still shines -- so much so that we miss her in the latter half of the movie. Another attraction to the film are the scenes shot on location in San Francisco, notably lacking any shots of the Golden Gate Bridge, which was under construction.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

2024 Toronto Marlies playoff stat leaders

Games played: Nick Abruzzese, Kieffer Bellows, Joseph Blandisi, Kyle Clifford, Dylan Gambrell, Dennis Hildeby, Roni Hirvonen, Mikko Kokkonen, Max Lajoie, Robert Mastrosimone, Topi Niemelä, Matteo Pietroniro, Jake Quillan, Marshall Rifai, Logan Shaw, Josiah Slavin, Zach Solow & Alex Steeves (3)

Goals: Marshall Rifai (3)

Assists: Kyle Clifford (3)

Points: Kyle Clifford & Marshall Rifai (4)

+/-: Kyle Clifford (+4)

PIM: Kyle Clifford (25)

Wins: Dennis Hildeby (1)

Fewest losses: Dennis Hildeby (2)

Fewest goals allowed: Dennis Hildeby (10)

Saves: Dennis Hildeby (86)

Shutouts: Dennis Hildeby (0)

0 notes

Text

La théorie de la croissance économique développée par Robert Solow, connue sous le nom de modèle de Solow ou modèle de croissance de Solow, est l’une des contributions majeures à l’économie et à la compréhension du processus de croissance économique. Robert Solow, un économiste américain, a présenté cette théorie dans les années 1950 et 1960. Son modèle cherche à expliquer les sources de la…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

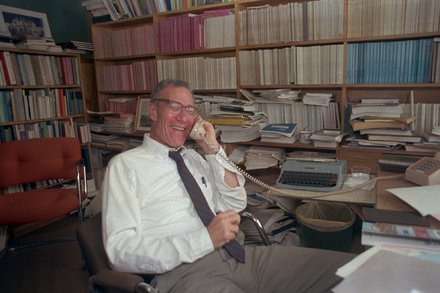

Institute Professor Emeritus Robert Solow, pathbreaking economist, dies at age 99

New Post has been published on https://thedigitalinsider.com/institute-professor-emeritus-robert-solow-pathbreaking-economist-dies-at-age-99/

Institute Professor Emeritus Robert Solow, pathbreaking economist, dies at age 99

MIT Institute Professor Emeritus Robert M. Solow, a groundbreaking economist whose work on technology and economic growth profoundly influenced the field, and whose ethos of engaged teaching and collegial collaboration deeply shaped MIT’s Department of Economics, died on Thursday. He was 99.

Solow’s research, especially a series of papers in the 1950s and 1960s, helped demonstrate at a fundamental level how modern economic growth occurs. As his work shows, technological advances, broadly defined, are responsible for the bulk of modern economic growth, more than simple population growth or capital expansion. This insight opened up a whole new series of research questions within academia, and influenced policymakers in many countries.

For these contributions, Solow was the recipient of the 1987 Nobel Prize in economics, with the citation mentioning his “exceptional contributions” as well as the “dramatic impact” of his work. In 2014, Solow was also awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor in the U.S., from President Barack Obama.

At MIT, Solow was also celebrated for his commitment to teaching in the classroom, and to engaging in ongoing scholarly discussions with colleagues and students, which he carried out with intellectual rigor, clear expression, and a continually affable, good-humored style. Hired by MIT in 1949, Solow was one of the core figures who helped turn the Department of Economics into a powerhouse program. After retirement, he was an Institute Professor Emeritus.

In all, Solow was affiliated with MIT for a remarkable 74 years.

“Bob Solow, who not only won a Nobel Prize but also saw four of his former students similarly honored, was a path-breaking researcher and extraordinary teacher,” says James Poterba, an economist and former head of MIT’s Department of Economics. “He laid the foundation for the modern study of economic growth and quantified the key role of technological progress in contributing to it. His legendary lectures, often delivered without notes, inspired generations of MIT students. A key architect of the post-war rise of the MIT Department of Economics, he was also a central contributor to its culture of comraderie and public-spiritedness that continues to this day.”

Robert Solow participates in an Infinite MIT oral history. See related links for transcript.

Video: MIT Infinite History Project

Home from the war, on to MIT

Robert Merton Solow was born on August 23, 1924, and grew up in Brooklyn, New York, where his father was a fur merchant. A standout student from early on, Solow skipped two grades in school, and earned a scholarship to attend Harvard University at age 16, in 1940. Two years later, after the U.S. had entered World War Two, Solow enlisted in the U.S. Army. Having learned some German in college, Solow spent much of his wartime service in Italy in seemingly risky circumstances, working in a company intercepting German radio signals, in specially equipped trucks just behind the front.

When the Allies won the war, he re-entered Harvard in 1945. Late that summer, Solow married Barbara “Bobby” Lewis, a Radcliffe College student whose interest in economics helped spur his own entry into the field. In short order, Solow finished his undergraduate degree and completed Harvard’s PhD program in economics, producing a PhD thesis on new methods of studying income inequality.

When Solow joined the MIT Department of Economics in 1949, it was a small program largely oriented around teaching. However, one faculty member, Paul Samuelson, was in the process of overhauling large portions of economics with his emphasis on mathematical rigor and formal analysis.

Samuelson and Solow, along with many colleagues from these early days — including Charles Kindleberger, Harold Freeman ’31, Cary Brown, Robert Bishop, and George Shultz PhD ’49, the future U.S. secretary of state — helped the program grow and thrive, while it added luminaries such as Franco Modigliani. By 1960, the MIT department was considered to be at the top of the discipline.

It was also considered to be an informal, open, student-friendly place — “the happiest economics department,” as a visiting professor from Harvard termed it. Solow often attributed that to Samuelson’s own lack of airs, telling an MIT interviewer in 2011, on the occasion of MIT’s 150th anniversary, “if you have the best economist in the world in the department, and he’s not being stuffy about anything it must be hard for anybody else to be stuffy.” But Solow’s personable approach to academic life heavily influenced the emerging departmental culture as well.

A new theory of economic growth

Solow’s own research took flight in the 1950s, when he started publishing his landmark work on technological change and growth, which altered the way economists thought about the subject. His 1956 paper, “A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth,” in the Quarterly Journal of Economics, presented a famous model outlining how under certain conditions, even a growing population with growing capital investment will not sustain economic growth. Instead, it is technological progress, considered broadly, that creates such growth over time.

In a 1957 follow-up paper, “Technical Change and the Aggregate Production Function,” in The Review of Economics and Statistics, Solow added new historical economic data showing this process at work, based on the U.S. economy in the first half of the 20th century. Here, Solow concluded that “Total factor productivity” — the term he created, encompassing all technological, cultural, educational, and other factors beyond population increases and basic capital investment — accounted for a whopping 80 percent of growth.

Beyond that, in 1960 Solow extended his analysis in a third paper, “Investment and Technical Progress,” modeling a scenario in which capital investment becomes more technologically sophisticated over time. All three papers were mentioned in the citation for Solow’s Nobel Prize — technically the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel — and together provided a framework for decades of continued research in economics.

Understanding the drivers of economic growth, Solow said during the 2011 interview, was an issue that “was in the air. It was sort of one of the outstanding problems.”

Before doing his research, Solow added, “I had taken it for granted like everybody else, that the main thing that pushed an economy to grow was the increase in population and the accumulation of capital goods … And I found that if you looked at the data with all of the theory you could bring to bear, you could not make that story hold water. And the only way of accounting for what we’d seen in the U.S. between 1909 and 1950-something was if the main driving force for growth had been what I chose to call technical progress. Meaning what was in my mind was improving technology, but also included improving skills.”

Solow’s work was quickly recognized as a breakthrough in the field. In 1961, he was awarded the John Bates Clark Medal, given by the American Economic Association to the best economist under the age of 40. Much later, in 2000, Solow was awarded the National Medal of Science. He was elected a member of the National Academy of Sciences, and a Fellow of the British Academy.

Solow had terms as president of the American Economic Association, and the Econometric Society. He also spent time working in the policy sphere. In the 1970s, Solow served as member and chairman of the Board of Directors of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. And from 1961 to 1962, Solow served on the Council of Economic Advisors in the Kennedy administration, along with prominent economists such as Kenneth Arrow and James Tobin.

“We thought we had one of the best economics departments in the country, sitting there in the Old Executive Office Building,” Solow quipped to MIT News in 2019.

Devoted to teaching

For all of his research accomplishments and policy service, Solow also thrived in the classroom, and as a committed, encouraging advisor to students.

“You only have really good ideas once in a while,” Solow told MIT News. “I would rather teach a really bright student than write a mildly interesting paper.”

When it came to teaching undergraduates, Solow would annually tear up his old lecture notes, and force himself to re-examine how he was presenting material to them. He came to believe he did his best teaching by the third time he lectured on a particular subject.

As a graduate advisor, Solow would put in long hours providing detailed feedback to students about their research papers, often reading their work in the evenings, across the living room from Barbara Solow — who also received a PhD from Harvard, and taught at Brandeis and Boston University, as a scholar of Irish economic history, as well as the Carribean slave trade.

Over time, Solow served as principal advisor to over 70 doctoral students, many of whom became highly accomplished economists. Four doctoral students for whom Solow was the main advisor — George Akerlof PhD ’66, Peter Diamond PhD ’63, William Nordhaus PhD ’67, and Joseph Stiglitz PhD ’67 —eventually won the Nobel Prize themselves. (One student who wrote an undergraduate economics thesis for Solow, H. Robert Horvitz ’68, also won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.)

“He was extremely generous with both his time and his ideas,” Akerlof told MIT News in 2019. As a graduate student, Akerlof found, “the faculty were there to greet students on the first day we arrived at MIT, and to give us advice. I mean, you would not expect the most distinguished professor at the best economics department to be there, waiting for you. That was extraordinary.”

Solow’s intellectual and professional commitment to his students, and his active mentorship, earned him life-long admiration from those who had studied with him.

“Paul Samuelson was royalty, but Bob was very much the prime minister running the country,” the economist Avinash Dixit PhD ’68 recalled, in remarks for a 90th-birthday gathering for Solow, in 2014.

As it happens, Samuelson and Solow worked for decades in the same common suite of offices, talking economics at length. Engaging with colleagues, Solow strongly felt, was one of the best ways to produce better scholarship.

“More than being pleasurable, I think it makes for good work,” Solow told MIT News. “Talking to your colleagues — or, in my case, standing at a blackboard with them and talking and scribbling — improves the product.”

For those fortunate enough to have been both students and colleagues of Solow, the remarkable economist’s passing evoked both sadness, and gratitude for all he contributed.

“I was fortunate to see many phases of the Bob Solow experience — to have him as an undergraduate teacher, where his class was widely viewed as the highlight of the economics curriculum, to see him as a dedicated thesis advisor, to have insightful research conversations, and to work with him as an external policy expert,” says Jonathan Gruber, current head of the MIT Department of Economics. “In every phase, Bob was amazing — always thoughtful, well-spoken, clear and kind. He is a role model for all economists.”

This article will be updated throughout the day.

#accounting#Administration#Advice#air#amazing#Analysis#anniversary#approach#Article#birthday#board#Born#Building#change#Collaboration#college#data#economic#Economics#economy#emphasis#factor#Faculty#flight#Foundation#framework#Fundamental#Future#generations#Global

0 notes

Text

Antonio Velardo shares: Robert M. Solow, Groundbreaking Economist and Nobelist, Dies at 99 by Robert D. Hershey Jr. and Michael M. Weinstein

By Robert D. Hershey Jr. and Michael M. Weinstein

His elegant work established that the main determinant of economic growth was technology, not growing capital and labor.

Published: December 21, 2023 at 06:46PM

from NYT Business https://ift.tt/DjUVP2S

via IFTTT

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

KILLDOZER (1974) – Episode 204 – Decades Of Horror 1970s

“How do you go about killing a machine? It’s too heavy to hang and it’s too big to put in the gas chamber.” Firing squad? Ole Sparky? Join your faithful Grue Crew – Doc Rotten, Chad Hunt, Bill Mulligan, Jeff Mohr – as they return to the boob tube for another memorable, made-for-TV, horror movie from the 1970s: Killdozer (1974)!

Decades of Horror 1970s

Episode 204 – Killdozer (1974)

Join the Crew on the Gruesome Magazine YouTube channel!

Subscribe today! And click the alert to get notified of new content!

https://youtube.com/gruesomemagazine

Decades of Horror 1970s is partnering with the WICKED HORROR TV CHANNEL (https://wickedhorrortv.com/) which now includes video episodes of the podcast and is available on Roku, AppleTV, Amazon FireTV, AndroidTV, and its online website across all OTT platforms, as well as mobile, tablet, and desktop.

After being possessed by a strange force in a meteorite it unearths, a giant bulldozer goes berserk and begins attacking the construction crew.

Director: Jerry London

Writing Credits: Theodore Sturgeon & Ed MacKillop (teleplay); Herbert F. Solow (adaptation); Theodore Sturgeon (novella, Astounding Science Fiction, Nov 1944)

Selected Cast:

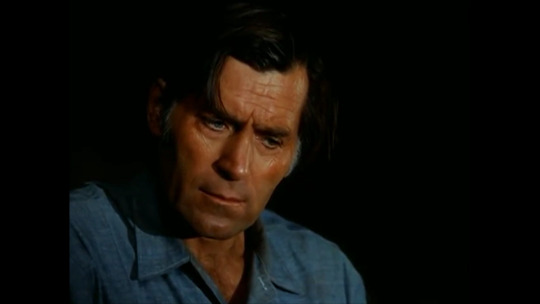

Clint Walker as Lloyd Kelly

Carl Betz as Dennis Holvig

Neville Brand as Chub Foster

James Wainwright as Dutch Krasner

Robert Urich as McCarthy

James A. Watson Jr. as Beltran

Look out, Duel (1971). Move over, The Car (1977). Talk to the hand, Maximum Overdrive (1986). ABC TV’s Killdozer (1974) is here to rule! Well, best intentions, eh? Based on a story by acclaimed writer Theodore Sturgeon, though he had little to do with the final script (according to the author’s account), this is the tale of a mysterious invisible force that possesses a Caterpillar D9 bulldozer to chase and mow down the cast (Clint Walker, Neville Brand, Carl Betz, Robert Urich, James Wainwright, James A. Watson Jr.) on a remote island off the coast of Africa. Originally criticized as being outlandish – not too far from the truth – the film has gained a following over time and has since become considered a cult classic. Often recommended by Patreon members and Decades of Horror fans, it’s finally time for the Grue-Crew to chime in with their thoughts.

At the time of this writing, Killdozer is available to stream from Plex. The film is available on physical media as a Blu-ray from Kino Lorber Studio Classics.

Gruesome Magazine’s Decades of Horror 1970s is part of the Decades of Horror two-week rotation with The Classic Era and the 1980s. In two weeks, the next episode, chosen by Chad, will be Death Game (1977), starring Sondra Locke, Collen Camp, and Seymour Cassel. Death Game was remade in 2015 as Knock Knock, directed by Eli Roth and starring Keanu Reeves. How does the original hold up?

We want to hear from you – the coolest, grooviest fans: comment on the site or email the Decades of Horror 1970s podcast hosts at [email protected].

Check out this episode!

0 notes

Text

Birthdays 8.23

Beer Birthdays

George W.C. Oland (1855)

Mario Celotto (1956)

Five Favorite Birthdays

Gene Kelly; actor, dancer (1912)

Edgar Lee Masters; writer (1868)

Keith Moon; rock drummer (1946)

Robert Mulligan; film director (1925)

Arnold Toynbee; economist (1852)

Famous Birthdays

August Ames; Canadian adult actress (1994)

Kenneth Arrow; economist (1921)

Kobe Bryant; Los Angeles Lakers G (1978)

Ernie Bushmiller; cartoonist (1905)

Scott Caan; actor (1976)

Alexander Calder; Scottish-American sculptor (1849)

Bob Crosby; swing singer and bandleader (1913)

Will Cuppy; humorist (1884)

Robert Curl; chemist (1933)

Jean Darling; actress and singer (1922)

Barbara Eden; actor (1934)

Bobby G.; singer (1953)

Jo Gwang-Jo; Korean philosopher (1482)

William Ernest Henley; English writer (1849)

Roger Greenaway; English singer-songwriter (1938)

William Ernest Henley; English poet (1849)

Jimi Jamison; rock singer (1951)

Sonny Jurgensen; Washington Redskins QB (1934)

Shelley Long; actor (1950)

Stanisław Lubieniecki; Polish astronomer (1623)

Edgar Lee Masters; writer (1868)

Vera Miles; actor (1929)

Robert Mulligan; film director (1925)

Oliver Hazard Perry; naval officer (1785)

River Phoenix; actor (1970)

Malvina Reynolds; folk singer (1900)

Galen Rowell; mountaineer and photographer (1940)

Mark Russell; satirist (1932)

Robert Merton Solow; economist (1924)

Vera Miles; actress (1929)

Jay Mohr; comedian, actor (1970)

Konstantin Novoselov; Russian-English physicist (1974)

Richard Sanders; actor and screenwriter (1940)

Marian Seldes; actress (1929)

Hamilton O. Smith; microbiologist (1931)

Robert Solow; economist (1924)

Rick Springfield; pop singer, actor (1949)

Linda Thompson; English folk-rock singer-songwriter (1947)

Keith Tyson; English painter and illustrator (1969)

Sarah Frances Whiting; physicist, astronomer (1847)

Tex Williams; singer (1917)

Pete Wilson; politician, 36th Gov. of Cal. (1933)

0 notes

Text

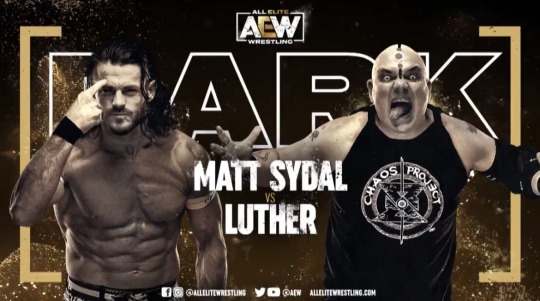

AEW DARK - EPISODE 84

Taped: April 7, 2021 Aired: April 13, 2021

Jacksonville, FL - Daily’s Place

Commentary: Excalibur, Taz, Jake Roberts, John Silver

-Christopher Daniels & Frankie Kazarian d. Jay Lyon & Midas Black

-Matt Sydal d. Luther

-Alan “5” Angels & 10 d. Hayden Backlund & Kit Sackett

-Colt Cabana d. Jake Manning

-Red Velvet & Big Swole d. Amber Nova & Queen Aminata

-Aaron Solow d. Fuego Del Sol

-Billy, Austin & Colten Gunn d. Mike Magnum, Andrew Palace & Stone Rockwell

-KiLynn King d. Madi Wrenkowski

-Matt Hardy d. Ken Broadway

-Evil Uno & Stu Grayson d. Vary Morales & Spencer Slade

-Britt Baker d. Shawna Reed

-Brian Cage & Ricky Starks d. Carlie Bravo & Dean Alexander

-Nyla Rose d. Leila Grey

-The Varsity Blonds d. Prince Kai & Will Allday

-Lance Archer d. Cole Karter

-Alex Reynolds d. Ryan Nemeth

0 notes

Text

Exodus

Consolidating fragmented supply chains through statecraft proved to be a potent jolt for enterprising industries in the 1910s. The success was replicated four decades later when the descendent of motorway expansion legislated the Interstate Highway System which became the crown jewel of President Dwight Eisenhower’s incumbency. Known as the Highway Act of 1956 it allocated $25b or the equivalent of $280b today for 41,000 miles of expressway over a decade by fronting 90 percent of costs shared with states. The asphalted ambition pared down travel times between coasts from upwards of two weeks by more than half before the close of the 1960s. A brisk five days of travel between New York to San Francisco had structural implications for the economy based on this civil engineering feat. Quite predictably Detroit automakers in particular were gifted a boom in annual sales by 48 percent between 1951 and 1965 as the change in road stock aroused the ubiquity of vehicles. Politics of mobility further reduced the friction of supply chains whilst simultaneously whetting the wanderlust of Americans as evidenced by the public capital’s intensity of use. After some stocktaking the return on investment approximated 20 percent for the economy due to the improvement in inbound and outbound logistics (Congressional Budget Office 1991).

America’s largest peacetime works program followed by the Panama Canal reimagined once more industrial development by carrying one-quarter of the country’s road traffic upon completion. Each dollar of cost apportioned to the superhighway yielded a six-fold return in productivity gains (Cox and Love 1998). Compared with rail and byways the Interstate saw roughly twenty-six times more traffic density in a testament to its speed and efficiency which changed America from a kaleidoscope of businesses into a single contiguous market. Any given lane services four thousand vehicles per hour in peak travel times so naturally such capacity elicited productivity growth in sectors reliant on transportation. Most lauded was how faster roads would optimize supply chains with the net effect of higher prosperity. Infrastructure spending of this species epitomized economist Robert Solow’s ideas on the mechanics of growth which hinges not so much on capital accumulation but productivity (1956). This nuanced exegesis intimates the number of factories on a company’s ledger is of little import compared with how efficiently they operate. Productivity matters more than capital intensity. America’s version of the Autobahn thus promised to strategically multiply growth rather than merely add to it by compressing time and space.

The Highway Act beyond its physical manifestation introduced industrywide savings as tractor-trailer costs declined by 17 percent translating into economies for consumers and their purchasing power. Americans saw their consumption rise commensurate with their dollars stretching further. When channeled into core business functions travel time reductions in the range of 60 percent were monetized to be worth $438b for Interstate users (Federal Highway Administration 1970). Companies revelled in this reality of transit costs no longer gnawing away at their margins in virtue of less outlays in fuel, wear and tear and labour hours. Rather than a passive investment this leviathan of a project in the postwar years brought about a windfall of wealth creation. A quarter of the nation’s productivity increase at the time resulted from the audacious 5 percent of GDP invested towards this single piece of infrastructure. The dividends were aplenty now that companies were poised to produce and distribute goods more swiftly which necessitated a hiring spree in keeping with the expansion of operations. Not only did Interstates provide a facelift to logistics but they indirectly became employment generators for a raft of industries downstream. Carmakers for instance grew by leaps and bounds by employing one out of six Americans (Sugrue 2012).

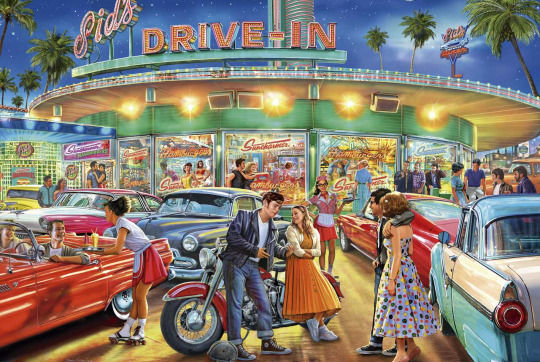

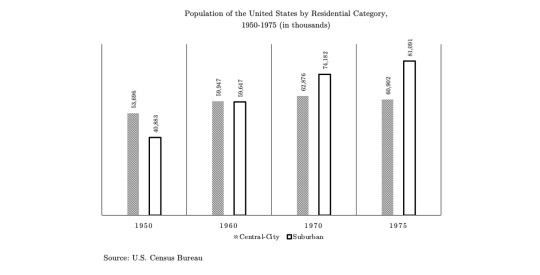

The golden age of infrastructure might have had its most profound effect on tertiary industries. One bellwether for the change afoot was the exodus towards the white-picketed suburbs that saw an increase in private and commercial real estate activity. By 1960 sixteen out of the largest twenty cities succumbed to significant population loss with a housing boom proliferating in their peripheries (Myers 1963). The cramped quarters of urban living became anathema to a growing-middle class whose love affair with backyard dimensions caused suburbs to grow by a factor of two from forty to eighty million between 1950 and 1975. President Eisenhower’s Interstates would personify the silhouette of modern America with cathedrals of capitalism in the form of shopping malls springing up next to these corridors. Culinary preferences were not spared either with drive-thru culture becoming a staple of the retail utopia which abounded in greenfield sites for developers. The centrifugal forces wrought by the Highway Act haemorrhaged demographics in cities towards these manicured enclaves as family formation in more verdant grounds appealed to WWII veterans. Suburbs invariably evolved into icons of middle-class aspiration around which scores of industries coalesced to profit from a migration spurred by Eisenhower.

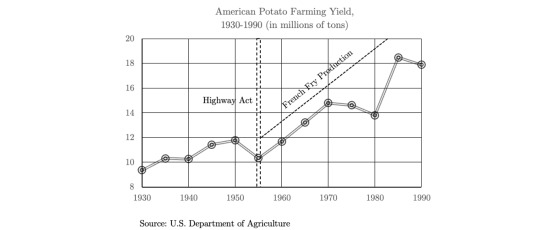

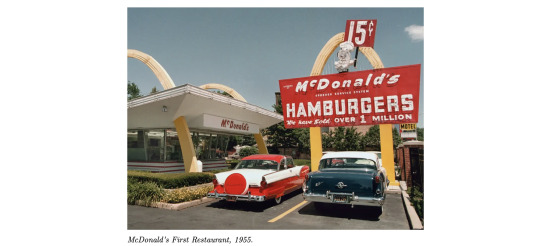

The industrial policy of the Highway Act did not operate in a vacuum instead beckoning a panoply of companies to service commuters and road trippers in new markets. Part of America’s mythology in the 1950s would be the surge in fast food eateries that popularized the hamburger and French fry between the likes of Dairy Queen, Burger King and McDonald’s. Highways were synonymous with the comfort food and its mass consumption could be read in the potato industry’s annual yield which reversed prior years of stagnation. Between 1961 and 1971 the franchise units adorned with the Golden Arches multiplied by 758 percent and even surpassed the United States Army as the largest dispenser of meals (Hackett 1976). Similarly the restaurant chain known as Kentucky Fried Chicken accounted for 6 percent of all broiler demand in America (Wilcox 1971: 24). It quickly came to pass that a franchise model disrupted the food industry’s traditional family-owned diner from drive-ins to drive-thrus wherein carhops would be bypassed. These establishments colonized the suburbs even to the point of oversaturating them as they jostled for marketshare amidst the halcyon years of suburbia. The fast-food industry’s rise to stardom was in no small part a corollary to how the Interstate transformed the gastronomy of American consumers.

0 notes