#Towton

Text

In the end, politics was an accretion of personal decisions, and that means that the personality of the protagonists cannot be left out of the discussion. It determined not only how they reacted to the situations in which they found themselves, but how others reacted to them. The growing support for Edward IV in 1461 must have owed something to the realisation that he would make an effective king - whereas his father never seems to have been regarded in that light.

--Rosemary Horrox, "Personalities and Politics", The Wars of the Roses (Problems in Focus), edited by A.J Pollard

...When the worst had happened, and civil war was a reality, the overwhelming imperative was to find some way of restoring order. At the level of high politics, what this entailed in practice was a rallying around the de facto king. The Wars of the Roses, far from weakening the monarchy, actually strengthened it, since the king was the only man able to surmount faction. In spite of (Henry VI’s) manifest failings, Richard, duke of York's criticism of the regime commanded little high-level support - and would have commanded even less but for the crown's alienation of the junior branch of the Nevilles, headed by York's brother-in-law the earl of Salisbury. York in fact never did attain the political viability to break the vicious circle of temporary ascendancy and political exclusion. It was his son, Edward, earl of March, who finally mustered enough support to take the throne. He was able to do so in part because the situation had been transformed by the country's descent into open war, which reduced the compulsion to uphold the king as the embodiment of stability. Once it was no longer a matter of averting war, but of stopping it, political opinion began to divide more evenly between Henry VI and his rival.

However, the crucial change may well have been York's own death at the Battle of Wakefield late in 1460. In the ensuing months Edward of York was able to present himself as the man who could mend the shattered political community. That self-identification with unity proved immensely potent, and it was not a role which could plausibly have been filled by his father. In the eyes of contemporaries, York had been the begetter of faction: a man tainted by his willingness to go to extremes.

#oof💀#I can't decide if this is more awkward or ironic#But it's nevertheless VERY interesting#Edward IV#Richard Duke of York#my post#wars of the roses#Edward still had to win Towton (ie: a military victory) to actually secure his kingship and bring over a lot of the nobility to his side#But this point is nonetheless very true - not just for his road to victory but also for the image he cultivated after he had won#It's very common to hear about how Edward IV was eventually viewed by many as a 'better' alternate to the throne than Henry VI#But what isn't acknowledged nearly as much is how by that logic he would've equally been viewed as a better alternate than his father#Ironically this entire point is made even clearer by the actions of York's own staunchest supporters ie the Nevilles#Certainly both Edward & Warwick learned their lesson from York's disastrous attempt at an acclamation in 1460#Considering how comparatively well-planned and well-executed Edward's own acclamation was in comparison#This is another reason I dislike how the Yorkists are often viewed and spoken of as a collective. the broader dynastic label tends to#minimize the differences in certain situations like this one or Richard's usurpation

22 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Not only had a significant section of the country, notably the Londoners and many in the south-east, lost faith in the Lancastrian king, but they had also become alienated from the Lancastrian cause itself as represented by the queen and her son. An alternative king had now become acceptable to many people of influence and standing in the country. A question still remains as to whether Margaret of Anjou was the cause of this situation, as her enemies maintained, or whether she was rather the victim of her circumstances. When it came to actual physical fighting, as a woman she was in a weak position, and she was no match for the challenge posed by the young, dynamic soldier, Edward, earl of March, whose success at Towton on 29 March 1461 clinched the Yorkist victory. Margaret, with her husband and her son, awaited news of the outcome of the battle from the safety of the city of York and, on hearing of the Lancastrian defeat, fled north over the border to Scotland.

Diana Dunn, "The Queen at War: The Role of Margaret of Anjou in the Wars of the Roses" in War and Society in Medieval and Early Modern Britain (ed. Diana Dunn, University of Liverpool Press, 2000)

#margaret of anjou#henry vi#edward of lancaster#edward iv#battle of towton#wars of the roses#historian: diana dunn

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

タウトン戦。タウトンの戦い(Battle of Towton)は、薔薇戦争中の戦いで、1461年3月29日の雪の日に行なわれた。死傷者2万を超える(恐らく約3万人)英国内の戦闘としては最も血なまぐさい戦いであった。

0 notes

Note

Seeing your views on Margaret of Anjou, I was told that Margaret of Anjou was firm, brave, but too radical, revengeful to the enemy and extreme political measures, which led to her failure. I want to know your views on the reasons for her failure?

Hi, sorry this took so long! I've been busy and this got very long. The short answer to all three, however, is that she had a shit-ton of bad luck.

The slightly extended version of is:

The Treaty of Tours which brought her to England had terrible terms for the English and thus terribly unpopular. As the face of the treaty, she was unfairly blamed for.

England was losing the Hundred Years War, badly. Her marriage was meant to bring peace but the only peace to be gained was through defeat and capitulation. Margaret was blamed for failing to live up to unrealistic expectations.

There was something of a succession crisis, the long wait for Margaret to conceive and give birth to an heir did nothing to easeit and only added to her unpopularity.

The long wait for an heir meant there was fertile ground for rumours and gossip, specifically the idea that she was an adulteress and Edward of Lancaster a bastard.

Henry VI's sudden mental breakdown, (probable) limited recovery and imprisonment left Margaret as the figurehead of Lancastrian rule and resistance. It made her the target for Yorkist propaganda attacks.

Following the Battle of Towton, the Lancastrians were in a weak position to negotiate with potential allies, meaning they made great concessions that were then seized upon by Yorkists to turn the general public against the Lancastrian side.

Severe weather hampered the Lancastrians on at least three occasions: Towton, Barnet and Margaret's return to England in 1471.

She lost. Yorkist rule continued to denigrate her and the Tudors weren't interested in challenging that idea.

Want more detail?

The Problem of Determining Personality

To start with, we don't know a whole lot about Margaret's personality. We don't know a whole lot about any medieval individual's personality, the evidence simply isn't there to tell us about their personal thoughts beyond brief flashes of insight. It's a fraught issue, as Rosemary Horrox points out, with reference to Margaret herself.

We also have to contend with the layers and layers of propagandistic narratives. Again, this is true for almost every figure in medieval history (cf. A. J. Pollard on Elizabeth Woodville). When we shift through the Lancastrian, French, Yorkist, Tudor and more narratives about Margaret, how do we know which one is telling the truth? The virago Yorkist writers derided is unlikely to be the true Margaret but that doesn't mean that the tireless heroine of French writers is the "true Margaret" either. Both images are stereotypes, both come from biased sources. Nor does acknowledging that the image of Margaret as the virago was a propagandistic creation that served Yorkist interests mean that Margaret must have been the exact opposite and she was really sugar, spice and all things nice.

These type of stereotypes are attractive to historians and historical fiction writers alike. They're simple but dramatic. They work well with other stereotyped figures, with "accepted" versions of history that are accepted because they've been repeated so often that they now seem true even if the evidence isn't there or doesn't tell us the things we think we know. It produces a simple, coherent narrative which confirms our own biases. The image of Margaret as radical, revenge-seeking and extreme is often tied to the narrative of Richard, Duke of York as a noble, hard-working and good man who was forced to rebel against his king (who is not rightful king, of course, because that's York) due to the plots and schemes of Margaret and her cronies. Margaret's inability and unwillingness to acknowledge and accept York's greatness becomes the reason for her defeat. She's just too petty and self-serving. She brings it upon herself. She could have been safe - but she unfairly and evilly attacked York and he was simply forced by her actions to rebel.

I don't find that view of York convincing. I don't find that view of Margaret convincing. It's too simplistic, too much of a children's tale where the good guys are so good and the bad guys so bad that the bad guy forces the good guy into any acts that are morally dubious. There's more than a little misogyny in it too, blaming a woman for the actions of a man.

"The Bad Queen" and Queenship

Margaret has long been seen as the "bad queen", a woman who abjectly failed as queenship and was the reason why the Wars of the Roses broke out. I've already discussed some of the issues with that view but I want to talk about a couple of other points.

One: the Lancastrians lost, which cemented Margaret's reputation. As Katherine J. Lewis has pointed out, if the Lancastrians had been successful, Margaret would have likely been celebrated for her bravery and steadfast loyalty that saw the restoration of her husband and son. Instead, they lost and the Yorkist narrative about her became the norm.

Two: Margaret appears to have behaved as a conventional queen for as long as possible. She did not arrive in England and immediately begin she-wolfing it up and instead tried to behave in a way that lived up to gender expectations, even when she was forced to move beyond them (cf. Helen Maurer's comment here).

Three: when we talk about the ideals of queenship, we have to realise that while these were kind of a job description, they were subjective and often based in misogynistic "ideals" of womanhood. e.g. "motherhood" reduces the queen to her reproductive ability and this was something she had little to no control over. An infertile queen is often deemed to have "failed" at the "most vital" aspect of queenship by modern historians and commentators (for an alternate view, see Kristen Geaman on Anne of Bohemia) but very rarely is there an acknowledgement of how misogynistic this standard is.

Margaret was not a popular queen before the Wars of the Roses began. She became queen in a situation where she was set up to inevitably fail. She arrived in England to pageants hailing her as a bringer of peace, as the figure to end the war with France, but the terms of the treaty that included her marriage contract ensured that any benefits she could bring were minimal. There was a short, 21-month peace, a paltry dowry, the outlay of considerable expense to bring her to England, and her father had little to no influence with Charles VII of France to be able to help any future negotiations.

Another factor was that the surrender of Maine and Anjou came to be widely associated with her marriage. It wasn't an official condition of the marriage but it does appear to have been promised at the same time. It was disastrously unpopular in England and it very likely inflamed tensions within the nobility. Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset held large amounts of territory in Maine and Anjou and was made Lieutenant of France to make up for these losses, which offended his predecessor in the role, Richard, Duke of York. It has been argued, though I'm not convinced, that York continuing in the role would have at least maintained, if not improved, the English position in France instead of the massive decline that followed.

None of this was Margaret's fault. She was 14 years old when her marriage was negotiated. She had no role in negotiations beyond the symbolic. There is also some thought that the English side was hamstrung by Henry VI's instructions to make a peace at any and all cost. We don't know how she felt about marrying Henry or about the surrender of Maine and Anjou beyond speculation based on preconceived ideas of what she was "like". We don't know what she was really like to guess how she felt about these things. And even if she was in favour of the surrender of Maine and Anjou, she was still a teenager when it happened. Are we really saying that a bunch of experienced adult men fell over themselves to do exactly what a teenage girl wanted even though it was disastrously bad for England?

Margaret had basically walked into a scenario where she had very little chance of being the peace-bringer she was expected to be and her popularity suffered as a result. She wasn't the one making choices - at best, she might have influenced others to make choices, but most of the problems with France that she was blamed for began before she set foot in England.

The Succession Crisis

Margaret also walked into a succession crisis.

Typically, the succession crisis tends to be talked about as occurring from after the death of Henry's last paternal uncle and his heir, Humphrey Duke of Gloucester, in 1447 but I would suggest that there was an underlying anxiety about the succession that predated Gloucester's death. Since 1435, Henry VI's one and only heir had been his ageing and childless uncle Gloucester (before 1435, Gloucester's elder brother, also childless, had been the heir), who was not terribly popular with Henry and his court. On one hand, Henry and his favourites did not want Gloucester to become king because they disliked him and his policies. From another perspective, Gloucester was getting on in years, childless, unmarried and possibly in poor health, so if he became king, he wouldn't be expected to reign long and if he managed to produce an heir before his death, the chance are this heir would still be in single digits when he succeeded the throne. If there was no child, the question of the succession was wide open. As it was, Gloucester died two years after Margaret's arrival and there was no longer a clear heir.

I know that you're probably thinking, "York, though. It's York." Well, yes and no. York probably had the claim with the least complications. He was Henry's closest male relative who had not descended through the female line or through a legitimised bastard line. But there were were two other lines that had viable claims to the throne: Somerset and Exeter.

Exeter's claim derived from from Elizabeth of Lancaster, the daughter of John of Gaunt and his first wife, Blanche of Lancaster, making her the full sister of Henry IV. Somerset's claim was derived from John Beaufort, Earl of Somerset who was the eldest son of Gaunt and his third wife, Katherine Swynford. The Beauforts had been born bastards but legitimised by both the Pope and by Richard II. This legitimisation did not contain any clauses barring them the throne (this was done under Letters Patent in Henry IV's reign), quite possibly because Richard appears to have chronically avoided making any pronouncements on the succession and quite possibly because the there was little reason to imagine the Beauforts in contention for the throne.

Somerset was probably Henry's preferred heir. Since Exeter derived his claim through the female line, naming him heir meant that the female line counted in the succession and if it did, York had a better claim to the throne than Exeter and Henry, as he was descended from Lionel of Antwerp (Gaunt's elder brother) through the female line. It risked exposing the weakness at the centre of the Lancastrian claim to the throne which would in turn would reveal the reigns of Henry's father and grandfather were illegitimate. York seems to have never been particularly close to Henry; as Michael Bennett pointed out about Richard II (who, like Henry, faced a similarly uncertain and difficult succession), it's hard to love your winding cloth. But Somerset was a favourite, a Lancastrian from a cadet line and Henry's closest living paternal relative who was of legitimate birth.

These competing claims and the uncertainty about who would succeed caused anxiety. If Henry died childless, who would become king? How would these claims be settled? Would there be civil war and strife? What would it mean if the Lancastrian dynasty came to an end and a new one began?

So it's easy to imagine the pressure on Margaret to conceive and bear a child was almost certainly immediate on her arrival to England. Bearing a child would help ease these anxieties considerably, continuing the Lancastrian dynasty, putting to rest any civil discord caused by competing claim and ensuring a peaceful succession. In view of the unpopularity of the marriage to Margaret, it would also be seen as having a legitimising the marriage.

The Long Wait For An Heir

Unfortunately, that didn't happen. It was eight years between Margaret's arrival in England and the birth of Edward of Lancaster.

We don't know why it took so long. There's speculation of course - a delay in consummating the marriage due to Margaret's youth, the stress and pressure of the situation, Henry being too pious for sex, Margaret undergoing rigorous fasting as part of religious devotion, Henry requiring a sex coach, Henry being the medieval equivalent of asexual and/or sex repulsed, or there being some subfertility issue. There's no real evidence, one way or the other.

Henry VI's sexuality and piety are one of those sort of myths of the Wars of the Roses, embedded in the narrative as a "truth" but lacking contemporary evidence (as Bertram Wolffe points out, there is little direct, contemporary evidence for Henry's piety, most appears in retrospect as part of an explanation for his failed kingship and part propaganda for the (Tudor-sponsored) efforts to canonise him as a saint). The evidence of a sex coach is based a historian failing to understand how a medieval king's bedrooms worked and going, "we don't know that these people in attendance on the king at night in his bedroom left when he had sex with his wife so... sex coach? Please buy my book!" We don't know that there was a delay in consummation or that Margaret was considered too young for sex (for comparison's sake, Henry's grandmother, Mary de Bohun, conceived her first son - Henry V - around her 15th birthday). Margaret herself complained of poor health caused by rigorous fasting during times of "many sufferings and tribulations" but we don't know that she was fasting throughout these early years. We don't have anything like medical records for Margaret (or Henry) to know how she tried to manage this childlessness.

But we generally don't know why a medieval couple was childless. Where we do have evidence, it's often speculative (e.g. Kristen Geaman's work on Anne of Bohemia suggests Anne suffered at least one miscarriage based on a letter she dictated).

What we do know is that Henry and Margaret never attempted to promote the image of having a chaste marriage, even though it would have provided a bulwark against criticism of their childless state - they were choosing the holy, pious option. The birth of Edward of Lancaster and Henry VI's joyous reaction to the news of Margaret's pregnancy also suggest that they were trying for a baby. I think this suggests there was some kind of uncontrollable issue, possibly medical, causing their childlessness than it being a deliberate choice to assign "blame" for. It was, in short, just bad luck.

The long wait for an heir meant the anxieties around the succession and continuation of the Lancastrian were not quickly eased. In some ways, they might have been exacerbated. Before his marriage to Margaret, there was no reason to believe that Henry would struggle to have children when he married (or at least, there is no evidence this was the case). Once married, though, Henry's continued childlessness began to appear to be an issue that couldn't be easily or quickly resolved, perhaps even being a permanent issue.

We know, too, that their childlessness was used to criticise them from as early as 1446, and Margaret was the chief target of this criticism. An example of this comes from 1448, where one felon in Canterbury gaol accused his neighbour in the isle of Thanet of saying:

oure quene was non abyl to be Quene of Inglond but and he were a pere of or a lord of this ream he woulde be on thaym that shuld hepe putte her doun for because that sche bereth no child and because that we have pryns in this land

There does seem to have been some view that in marrying Margaret, Henry had betrayed his promise to marry a daughter of the Count of Armagnac and the lack of children from their marriage could be seen as a sign of God's disapproval. It would have added to the unpopularity Margaret was already facing.

While the news of Margaret's pregnancy does seem to have been greeted with joy, the long wait for such news had exposed Margaret to ample criticism and hatred. It made it easy for the allegations of Margaret's adultery and Edward of Lancaster's illegitimacy to take root. It meant that when Henry VI had his breakdown, there was no son who could serve even nominally as a regent for him and the question of who was to govern while Henry was incapable exposed the conflicts between York and Henry and York and Somerset.

Conflict with York

A lot of the conflict between York and Lancaster began with York's quarrel with Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset. Somerset was considered a favourite of Henry VI and Margaret but we don't know how much Margaret was responsible for his position in comparison to Henry or how much York's quarrel with him was really him quarrelling with the crown without openly doing so and risking a charge of treason. It does seem likely, imo, that Margaret had sympathies with Somerset given her husband evidently trusted him, but we don't know if that's true and even if it is, it was Henry VI who ostensibly promoted Somerset.

Despite the retrospective reading we put on the events leading up to the outbreak of war with the First Battle of St. Albans, we lack surviving evidence for Margaret and York being in direct hostility to each other. As Helen Maurer says:

If there is no concrete evidence of hostility between Margaret prior to the crisis of 1453-54, there is some indication that they were on reasonably good terms. York's recent biographer, P.A. Johnson goes so far to characterise Margaret as a 'politically neutral figure', whose attitude prior to January 1454 was 'if anything sympathetic to York'.

There is no evidence that York opposed Margaret's marriage to Henry. We have evidence of Margaret intervening in a property dispute in York's favour and giving York and his servants' generous New Year's gifts. The gifts to his servants in 1453 were of the same value as she gave the to the servants of Somerset and Cardinal Kemp so there was no deliberate slight there. In 1447, they were higher than the gifts she gave the Duke of Gloucester's servants (although alienated from Henry VI, Gloucester did outrank York so you'd expect his servants to get the more valuable gifts), the archbishop of Canterbury and duchesses of Bedford and Buckingham. Maurer speculates this was to reassure York in the face of his appointment to the lieutenancy of Ireland. We also have evidence of an outwardly cordial relationship between Margaret and Cecily in the early 1450s. It is not enough to suggest Margaret and Cecily were friends or what they really felt about each other but it does suggest they were both invested in keeping up at least the facade of cordiality.

The relationship between Margaret and York did sour some point. It's impossible to know what was the fatal blow was or who was the first to turn hostile. It may have been Margaret's attempt to claim the regency when Henry VI suffered his breakdown, it may have been York's imprisonment of Somerset during his protectorship, it may have been when York lost the protectorship, it may have been the rumours of York's involvement in William de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk's murder in 1450.

Maurer notes that Margaret probably viewed the First Battle of St. Albans as an alarming attack on Henry's royal authority by York. She would not be wrong to do so. York may have felt justified and may have been justified in taking action to remove the individual he saw as a threat to his own authority - Somerset - but he raised his banners and fought a battle against his king. A battle where the king, Margaret's husband, had been injured. Regardless of whether or not York was "justified" or whether or not Henry pardoned him, his behaviour was, actually, treasonous (and it is likely he was only pardoned because Henry felt forced into it).

We can argue about the semantics and justifications for York's behaviour but it doesn't really matter when it comes to Margaret's reaction. York had raised an army against his sovereign and fought against his sovereign's own forces in a battle where his sovereign was wounded in the neck. There is no world in which Margaret would not see York as a threat to her family after this. If we argue that York was justified in this action because he perceived (correctly or not) that Somerset was a threat to him, then we must also accept that Margaret had every justification in viewing York as a threat to her family.

I tend to get the feeling that by 1456, Margaret and York were both in the same position. They were at a point where they viewed each other as a threat to the safety of their position and family. Whether one was more justified than the other is impossible to say. It's likely, though, that York held considerably more responsibility that the myth of him as the noble-hearted man forced to rebel to save himself.

The Problem of Henry VI

Another factor in "who do we blame for the Wars of the Roses" is Henry VI himself. We don't know when he began ruling in his own right and what periods, if any, he was unable to rule beyond the breakdown of 1453-54. We don't really know if the criticisms of his favourites, i.e. Suffolk and Somerset, were really criticisms of individuals who were ruling for him or if they were more in line with the attacks on the favourites of Edward II and Richard II. In the case of Richard II, the Lords Appellant maintained the image of loyally serving Richard while purging his household, threatening him with deposition, executing his friends, and placing themselves in positions of power by claiming that they were merely rescuing the king from the influence and bad advice of his evil councillors. This doesn't mean they didn't also have a grudge against the king's favourites, that their attack on them didn't really matter (after all, they killed a lot of them), but by focusing on the favourites, they maintained the image of loyalty to the king which helped them sidestep a charge of treason (though they also forced Richard to pardon them) and maintain popular support.

All of that is just to say that this may very well have been the case with Henry VI. York's attacks on Somerset (and maybe Suffolk, since he was rumoured to be involved in Suffolk's downfall and murder) may have simply been an attack on Somerset, perhaps justified or not, but York may have also been using Somerset as a proxy for Henry.

If he did, his quarrel could, at its core, actually be with Henry. It also raises the possibility that, after Somerset's death at the First Battle of St Albans, Margaret was simply the last one standing between York and Henry and so became the proxy for his attacks on Henry. This only intensified once York gained custody of Henry, and Margaret, with Edward of Lancaster, was out of reach and leading Lancastrian resistance.

We know that Tudor efforts to rehabilitate and canonise Henry tended to place more blame onto Margaret to absolve Henry of blame. All of this means that in terms of "how responsible, really, was Margaret for the policy decisions that alienated York?", we simply don't know. She may have served as a receptacle for blame (though personally I think she was more involved than not) or been the prime actor but we can't negate the possibility that some of the things she was blamed for were actually Henry's fault.

On the subject of Henry's mental illness... obviously, neither he or anyone else are to blame for it. Certainly, no one wakes up and goes "I know, now I shall have a deliberating mental illness that will ruin the kingdom, I totally want and will this to happen". But it did make things... very difficult. The medieval monarchy just wasn't set up to deal with a king with a severe, incapacitating mental illness (this was also the case with Charles VI of France). It tended to aggravate factionalism as nobles jostled against each other for power and influence. It placed the queen in an unenviable position of trying to protect her family and govern for the king while also appearing politically neutral, above factionalism and still living up to the ideals of queenship and only wielding soft power. Even if Margaret had managed to be appointed as regent for Henry, the case of Isabeau of Bavaria who had been regent for Charles VI suggests she wouldn't have fared much better.

On top of that, Henry's breakdown came at a bad time. He was unable to recognise Edward of Lancaster as his son upon his birth, which may well have provided some of the initial fodder for the rumours of Edward's illegitimacy. Once again: none of this was Henry's fault but it all had an impact on how much Margaret was viewed and blamed for Lancastrian failures.

Military Defeat

Margaret was widely regarded as the head of the Lancastrians and very likely this was true during the times when Henry VI was unable to rule (i.e. due to mental illness or breakdown, during his imprisonment by Edward IV). However, she was not a military commander and there is no evidence she ever donned armour or was present at any battle (we know she was in Scotland at the Battle of Wakefield, not personally overseeing any indignities heaped on Richard, Duke of York's corpse, for example). When she was travelling with the army when a battle took place, she probably stayed nearby in reasonably secure locations, such as a castle or abbey, a short distance away from the battlefield.

Responsibility for the Lancastrians' military defeats should be laid at the feet of those who actually commanded the Lancastrian forces, not Margaret. We don't know if the Lancastrians had better commanders to say that was Margaret's fault for not appointing better ones (and given the position was often granted to those of high rank, this seems likely - to appoint a man of greater ability but lesser rank risked disaster, as the narratives about the French defeat at Agincourt tells us). This is something more down to misfortune than any choice Margaret could have made. We know that Margaret had wanted to return to France following the news of the Earl of Warwick's defeat and death at the Battle of Barnet but was overruled or convinced otherwise by other Lancastrians. Had she gotten her way, the Lancastrians may never have gotten another chance (or at least a better chance) to challenge Edward IV but they probably would have survived.

There were also elements of bad luck in the Lancastrians' military defeats. The Lancastrian forces at Towton were blinded by the snow and their arrows ineffective against the wind. At Barnet, a heavy fog caused confusion amongst the troops. Storms delayed Margaret and Edward of Lancaster's return to England in 1471; had they arrived earlier they might have been able to take a better position or unite with Jasper Tudor's forces and won the Battle of Tewkesbury. Had the weather been against Edward IV and the Yorkist forces at Towton or at Barnet, had Edward IV's return been delayed by storms - well, the Lancastrians might have won.

This isn't to say that nothing was Margaret's fault. Margaret's delay at returning to England during the readeption was also partially credited to her own mistrust of the situation (a fair if ultimately fatal judgement, given the risk involved to her son and Warwick's untrustworthiness as an ally). The delay meant that Warwick struggled to muster forces under his own authority to deal with Yorkist resistance. This situation wasn't all her fault, though. Her delay was also caused by Louis XII of France, who had refused to let her leave until he got guarantees from Warwick about English support against Burgundy and the storms mentioned above. Another factor is that Warwick was simply reaping what he had sowed - very few Lancastrians had reason to trust the man who had been the chief ally of York against Henry VI, who had put Edward IV on the throne, then attempted to crown George, Duke of Clarence before allying himself with Margaret. He also seems to have been heavily involved in the creation and promotion of the stories slandering Margaret and her son.

We should also be wary of suggesting, as B. M. Cron does, that Margaret of Anjou was partly to blame for her son's defeat and death at Tewkesbury because she didn't let him fight in battle before Tewkesbury. For a start, Lancastrian hopes rested on Edward's survival. He was the viable alternative to Yorkist rule, the figure around whom opposition could gather, and the future of the dynasty. Putting him at risk was a very bad decision. His death meant the end of Lancastrian hopes.

Secondly, Tewkesbury was the first major battle he was actually of an age to fight at. Was he supposed to fight at Towton when he was 8? Hedgeley Moor or Hexham when he was 11? Thirdly, from the few accounts of his time in exile, we know he was military-minded and dedicated to martial exercises so it seems he was prepared as much as was safely possible. Finally, it is unclear whether Edward engaged in the battle proper or whether he was killed attempting to escape when it became clear the Lancastrians had lost.

Summing Up

In short, there were a lot of factors in Margaret's failure and a lot of them compounded on other. Her initial unpopularity only grew as the the English position in France weakened and as the years went by with no sign of an heir. As unrest broke out and Henry was incapable of responding or ruling, Margaret became the de facto head of the Lancastrian court and the focal point for anger at the way things were being governed. Yorkist and later Tudor propaganda built on all these factors, depicting her as the central flaw in Lancastrian rule, the one reason for its failure.

We simply don't know what Margaret was really like. The image of her as a radical, extreme figure bent on revenge fits into narratives that imagines Richard, Duke of York was faultless in his actions, that she had pushed him to an extreme and he reacted in order to save his own life. The idea that Margaret could have felt similarly threatened by York's actions is never once considered, yet she had every reason to fear him.

Do I think Margaret was entirely the innocent in the Wars of the Roses? No. Of course not. But she probably was at fault for far less than is typically attributed to her.

#asks#anon#i think more than anything that we need to be far more sceptical of yorkist narratives than we are#margaret and edward of lancaster were living figures who served as a focal point for resistance against yorkist rule#of course the yorkists were going to use propaganda to denigrate them and try to manage the problem#margaret of anjou

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

So here is my collection of books from Osprey Publishing based around the Middle Ages, in this case 1000's to 1500's. 15 in total, which is the majority of my collection. Although I do think one is missing.

Going from top to bottom-

Top row:

Castagnaro 1387

Campaldino 1289

European Medieval Tactics (2)

Forces of the Hanseatic League

Towton 1461

Tewkesbury 1471

Middle row-

Teutonic Knight vs Lithuanian Warrior

Mongol Warrior vs European Knight

Otterburn 1388

Bosworth 1485

Longbowman vs Crossbowman

Lewes and Evesham 1264-65

Bottom row-

Viking Warrior vs Anglo-Saxon Warrior

Viking Warrior vs Frankish Warrior

Shrewsbury 1403

Knights at Tournament

Medieval Indian Armies (1)

Medieval European Armies

So... yeah. Nerd I am, and a self-avowed armchair Medievalist. But it's such an interesting topic, especially the military side of it especially since there really is a lot more to the Medieval period than what people think.

39 notes

·

View notes

Note

Where there any ideological differences between the Lancastrians and Yorkists (both the families and their supports)?

The Wars of the Roses was largely a dynastic struggle over the throne and royal patronage, but there were roots in earlier political struggles during the reign of Henry VI between what we could call a "war party" faction and a "peace party" faction.

Broadly speaking, the "war party" faction was led by people like Richard Duke of York and Richard Neville, and they tended to favor a continuation of the Hundred Years War, an alliance with Burgundy, disapproval of the King's marriage and the Queen's overly-active role in government, more royal efforts to improve law and order, and a crackdown on rampant corruption and favoritism that saw royal land distributed to court favorites, sapping royal finances.

Broadly speaking, the "peace party" faction was led by Margaret d'Anjou and her favorites like Somerset and Stafford. They tended to favor an end to the Hundred Years War, an alliance with France, obviously they favored the king's marriage and the Queen's active role in government, and they generally blamed problems in royal government on York's rebellious factionalism and emphasized that the royal prerogatives ought not to be questioned.

However, a lot of that stuff fell by the wayside once the fighting started - England couldn't really fight a civil war and war with France at the same time, Suffolk was dead, and efforts to deal with law and order, corruption, and royal finances would all have to wait until the fighting died down after Towton, and then again after Tewkesbury.

52 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, I want to know if Henry VII and Elizabeth of York got married to unite two families that had been hostile for many years, did the multiple rebellions of the York Party during the Tudor dynasty mean that this wish was thwarted? Or are these rebellious Yorkers mostly supporters of Richard III rather than Edward IV? How did the hundreds of English nobles who were exiled with Henry Tudor fare during the Tudor dynasty? Do they agree with the Tudor dynasty? I heard that many Yorkers expressed joy when Henry VIII ascended the throne?

Hello! @blackboar answered a similar ask (here) and I agree with most of their points. The purpose of Henry and Elizabeth's marriage was to unite two very specific rival claims which could (and did) mean more stability for the realm in the long run**. However, other claims were still around in the form of the cadet York branches headed by George of Clarence's children and the de la Poles (the children of Edward IV's sister) as well as the claim headed by the Duke of Buckingham. Most of the English political elite was already in support of Edward IV's direct heirs and by extension to Henry VII but ultimately anyone discontented with the Henry's regime could always support those other claims. That doesn't mean Elizabeth and Henry's marriage failed its purpose.

How did the hundreds of English nobles who were exiled with Henry Tudor fare during the Tudor dynasty?

They were restored to the positions they lost when they rebelled against Richard III and Henry VII granted offices/rewards to several of them. Most of Edward IV's councillors received a place in Henry VII's council too and were favoured by him.

Do they agree with the Tudor dynasty? I heard that many Yorkers expressed joy when Henry VIII ascended the throne?

Considering they remained almost two years with Henry in exile, yes. As to how Henry VII was perceived after he ascended the throne, the continuator of the Croyland Chronicle said that 'he [Henry] began to receive the praises of all as though he had been an angel sent down from heaven, through whom God had deigned to visit His people, and to deliver it from the evils with which it had hitherto, beyond measure, been afflicted.' This is not Croyland's opinion of Henry (as ricardians like to claim) but rather his retelling of the events and the actions of the people around him, very much punctuated by irony as well.

____________

** Although the political/ruling elite was already consistely united behind Edward IV, it's difficult to measure the feelings still surviving in the popular imagination. Henry VI was a very popular saint and his memory was intensely revered to the point that Edward IV tried to suppress his cult. There were likely some political aspects to it as every other cult dedicated to 'political martyrs' in that century did. Henry VII's reconciling discourse to the realm touched on feelings that were, presumably, still very much alive in popular memory. 20,000 or more englishmen died in a single battle between Lancaster and York (Towton) in the 1460s. I don't think people had completely recovered from the memory of those battles yet. We should never downsize the Wars of the Roses to an event that involved the ruling elites only. Common people lived and died in those wars and Edward IV, Warwick, Richard III and Henry VII all tried to dialogue with their aspirations and fears. So in a sense Henry VII's reconciling discourse was very much propaganda, but it most likely wasn't baseless propaganda rooted in no popular sentiment, as propaganda very rarely (if ever) is.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

the bloodiest battle being fought on english soil being the battle of towton boggles my mind... not in that it was a violent medieval battle but in that it is to this dat the deadliest war fought on english soil. that's not indicative of anything about medieval society so much as it speaks a lot to england as the home of an empire which has had very few battles fought in it in the modern day. as a general rule modern technology is more deadly and yet a battle fought in 1461 was the bloodiest battle to be fought in england. it's bizarre

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Duelists of the Roses Character Profiles - Yorkists/The Whites

Name: Christian ‘Seto’ Rosenkreuz

Deck Leader: Blue-Eyes White Dragon

Location: Stonehenge, England

Pre-Duel Dialogue: “You’re here much sooner than I expected. I knew that Crawford would turn on us one day. But I didn’t expect the tide of battle to turn so soon. Actually, Crawford’s betrayal and the fall of the Yorkists matter not to me. All I hoped from this tiresome struggle was to find an opponent worthy of my attention! When I knew you’d been summoned I chose to wait. Each time a member of my Rose Crusaders fell before you I shivered in anticipation. Once you beat the final member I knew you were ready to face me! Long have I starved to best a duelist equal in power to me, hungered to best such an opponent in battle! You wish to have my Rose Card? Then take it from me! Face me in battle, Duelist!”

Player Win Dialogue: “Well done, Duelist. I may have lost, but my heart sings with the joy of having faced you in battle.”

Name: Weevil Underwood

Deck Leader: Basic Insect

Location: Chester, England

Pre-Duel Dialogue: “Hehehe. So, you’re the legendary Rose Duelist. Prepare to face the wrath of my Insect deck!”

Player Win Dialogue: “Nooo! I lost! This can’t be happening!”

Name: Rex Raptor

Deck Leader: Two-Headed King Rex

Location: Tewkesbury, England

Pre-Duel Dialogue: “The Rose Duelist, eh? I’m not impressed. In fact, I’ll crush you to a pulp with my Dinosaur deck!”

Player Win Dialogue: “What?! Me!? Lose?! I don’t believe it!”

Name: Necromancer

Deck Leader: Pumpking the King of Ghosts

Location: Exeter, England

Pre-Duel Dialogue: “Oooh, my Zombie deck hungers for a taste of you.”

Player Win Dialogue: “Argh! You’d be a fool if you think you’ve seen the last of me!”

Name: Darkness Ruler

Deck Leader: King of Yamimakai

Location: St. Albans, England

Pre-Duel Dialogue: “You dare challenge the Dark deck of the Darkness Ruler?! Rose Duelist or not, you don’t stand a chance!”

Player Win Dialogue: “No! How can it be? How could I lose!?”

Name: Keith

Deck Leader: Slot Machine

Location: Towton, England

Pre-Duel Dialogue: “So, you’ve managed to beat a few minor duelists. Well let’s see how you fare against my Machine deck!”

Player Win Dialogue: “I can’t believe you actually beat me! Me! The ‘Card Professor’ of the Rose Crusaders!”

Name: Labyrinth Ruler

Deck Leader: Monster Tamer

Location: Newcastle, England

Pre-Duel Dialogue: “What brings you to this northernmost region? Lost? If you want some directions, you’ll have to beat me first!”

Player Win Dialogue: “Unbelievable! You’ve won yourself a light to guide you out of this labyrinth!”

Name: Lord Pegasus Crawford (Thomas Stanley)

Deck Leader: Illusionist Faceless Mage

Location: Lancashire, England

Notes: Has a son that is being held hostage by Richard Slysheen (Richard III).

Pre-Duel Dialogue: “Wow! So you’re the famed Rose Duelist! I am Pegasus Crawford, the Champion of the Northlands, the noblest of Yorkists, and master of the Rose Crusaders. I am also known to some as Thomas Stanley, or Lord Stanley to my friends. Seto has told me much about you, dear Duelist. Seto has taught me a thing or two about dueling. So, come on! Let’s duel!”

Player Win Dialogue: “You must be joking! Me? Lose? Never! Oh dear... You might be stronger than Seto... I really enjoyed that! I’ve learned a lot from you. In fact, you’ve done wonders for my game! Oh, by the way: I’m afraid I don’t have any Rose Cards. Sorry.”

Name: Ishtar

Deck Leader: Witch of the Black Forest

Location: Isle of Man, England

Pre-Duel Dialogue: “Amazing. I never thought you would reach the point where you could challenge me. Too bad that it all has to end here...”

Player Win Dialogue: “I’m not surprised, you know. I knew I was destined for defeat. I can live with that.”

Name: Richard Slysheen of York (Richard III)

Deck Leader: Battle Steer

Location: Bosworth, England

Pre-Duel Dialogue: “I see you’ve got Rose Cards! You must be one of Lord Crawford’s Rose Crusaders. Your timing couldn’t be better! When I heard Yugi had landed, I rushed my troops to the front. However, I arrived much too early. It will be some time before Lord Crawford and his men arrive. In the meantime, why don’t we play a duel or two. I learned a trick or two from Seto that I’d like to try out. It’s not every day that you have the great opportunity to play the great King Richard III of England! How about it?”

Player Win Dialogue: “Drat! I lost!”

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Battle of Towton in 1461 was the largest, bloodiest battle England has ever seen. The skeletons of its victims show just how brutal the fighting really was.

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

what did cicely neville do in edward iv's reign?

Hi! Cecily’s entire role during Edward IV’s reign is too long and complex to fully get into right now, so this is just going to be a very brief overview. It’s also not going to touch on her relationship with her daughter-in-law Elizabeth, even though that's somewhat relevant here in some aspects, because that’s also too complex and speculatory.

Ironically, despite the Duke of York’s claims to kingship, it was only after his death and during her widowhood that Cecily Neville truly emerged as a “quasi-queen”. After her son Edward IV had been acclaimed as King in London, and before he left for Towton with the other lords, he summoned the mayor and “all the notables of London” to gather and “recommended them to the duchess his mother”. During his absence, Cecily would preside over his household in Baynard Castle and was probably meant to act as his representative of sorts in the city. After his kingship was more firmly established, Cecily primarily resided at Westminster with him from 1461-64 and regularly accompanied him on several ceremonial and political occasions, such as their visit to Canterbury where she was magnificently welcomed. She also appears to have had a great deal of personal and political influence with her son: Nicholas O’Flanagan, the contemporary Bishop of Elpin, observed in the first few years of Edward IV's reign, his mother could “rule the king as she pleases.”

Cecily’s role demonstrably changed after Edward’s marriage to Elizabeth Woodville in 1464. She remained the second-highest ranked woman in the country, but she took a significant step back from high politics (a la Joan of Kent after her son’s marriage to Anne of Bohemia). That does not mean that either of them suddenly became apolitical or uninvolved: quite the opposite*. Cecily remained the head of a large household, her administration supported her son’s, she continued to support a few religious institutions, she engaged in trade, she launched court cases, and she clearly inspired loyalty among her affinity. All of this was fairly standard for a medieval noblewoman, but was naturally enhanced by Cecily’s own prominent royal status. Cecily was godmother to at least three of the royal children: Elizabeth of York, her namesake Cecily, and the youngest child, Bridget. She also played a role in reconciling her son George to the Yorkist cause in 1471, though she did not have the spearheading role which has often been erroneously credited to her by historians (ie: “engineering peace between her warring sons”); instead, it was her daughters Anne and Margaret who took the leading role in achieving the reconciliation, while Cecily probably aided them. She was also clearly perceived to be influential with Edward IV, best evidenced by how the mayors of Norwich petitioned her to aid them against the Duke of Suffolk in 1480, though we don’t actually know the result of Cecily’s intervention to judge whether it succeeded or how effective it was**. Regardless, though, she evidently had a much lower national profile during these years.

(On a more personal level, we also have a very sweet anecdote from Elizabeth Stonor who spoke of a meeting between Cecily and Edward in October 1476 at Greenwich: 'and ther I sawe the metyng betwyne the Kynge and my ladye his Modyr. And trewly me thowght it was a very good syght’.)

Cecily’s numerous titles are also interesting. Immediately after Edward IV’s ascension, she called herself “the Kyngs Moder, Duchess of York”. Variations of the title included references to her late husband, but she primarily defined herself in relation to her son, through whom her current position and power derived. As Laynesmith says: "narrative accounts, particularly chronicles, had naturally used the phrase ‘the king’s mother’ to describe women in the past, especially Joan of Kent. However, it was Cecily who turned this into a specific title in her letters and on her seals." A few months after Edward's marriage was announced, Cecily adopted a new title, now styling herself as: “By the ryghtful enheritors Wyffe late of the Regne off Englande & of Fraunce & off ye lordschyppe off yrlonde, the kynges mowder ye Duchesse of Yorke.” This referenced the Yorkist perception of her husband, Richard Duke of York, who was called the "true and indubitable heir" of England. In 1477, a herald for the wedding of her grandson Richard of Shrewsbury styled Cecily as “the right high and excellent Princesse and Queene of right, Cicelie, Mother to the Kinge”. This was once again linked to her husband’s status: Cecily described him in her letters as “in right King of England and of France and lord of Ireland”. All in all, Cecily’s various designations appear to have been designed to signify her own importance within the regime, to uphold the claim of her late husband, and to strengthen Edward IV’s position by promoting him as the son of the supposedly rightful heir. It’s also very possible, as Laynesmith has suggested, that “it was as her queenly power diminished [after the early 1460s] that her claims to queenship were more elaborately emphasized in wax and on parchment”.

Cecily’s role and prominence, and how it changed overtime, is best demonstrated by the number of times English subjects offered prayers for her soul in return for grants. Between June 1461 and September 1464, there are twelve instances of grants made to people who offered prayers for her. (To compare, during the first three years of Elizabeth Woodville's queenship, there were sixteen grants of the same type. So, Cecily didn't quite reach the level of the queen, but she came close; it was quintessential "quasi-queenship"). However, mentions of Cecily dramatically deceased following Edward IV's marriage: over the next 19 years till 1483, she is only mentioned five times, and in all cases Elizabeth Woodville was also listed before she was. Three of these mentions are in 1465, likely reflecting contemporary unease with her son's controversial marriage and the perceived unsuitable origins of the new queen. After that, however, Cecily is mentioned only twice: once in 1476 and once in 1481, with the latter being a grant to her own son-in-law Thomas St. Leger***. This fits well with what I mentioned above about her quasi-queenship in the early 1460s, followed by a much more reduced role and lower national profile in the future years.

Hope this helps!

*Oddly, Cecily is not mentioned at all in contemporary reports for her daughter Margaret’s wedding. Laynesmith believes that she was unwell, and that may as well be true, but Margaret's celebrations went on for a great period of time and it does seem conspicuous that Cecily was entirely absent from them all. It's also worth noting that a letter from the Milanese ambassador Giovanni Pietro Panicharolla on the marriage wrote that "the king, the queen, her father, and the king's brothers are all disposed to it" (sidenote: it's VERY interesting that the queen's father is mentioned before the king's own brothers and male heirs) but made no mention of Cecily. Nor, iirc, was she mentioned in the tournament held to celebrate Anglo-Burgundian relations. It does clearly seem as though Cecily did not play a notable role in the marriage, and relevant diplomacy, at all. (Laynesmith's claim that Cecily had "helped lay the ground for" the marriage because she *checks notes* dispatched both her sons to Burgundy in middle of a civil war 7 years earlier, with many fluctuations in Anglo-Burgundian relations in between, is, I'm sorry to say, nonsense).

** Laynesmith believes that "Cecily’s intervention to control Suffolk perhaps marked a turning point in the duke’s violent career because when he resorted to force again the following summer his victim successfully reclaimed the manor from which he had personally ejected her." I think that Laynesmith is being far too assumptive and that we don’t even know the result of Cecily’s intervention in 1480 to somehow credit her with entirely different case one year later that did not even involve her, lol.

***Even more oddly, Cecily’s own son Richard didn’t include her among the list for who to offer prayers for in his college in Middleham in 1478. This was despite the fact that he had included Edward IV, Elizabeth Woodville, his wife Anne, his sisters, his dead brothers and his dead father. It’s incredibly striking, and I wonder what could have happened to cause her exclusion, especially since she was included in religious foundations by both Edward and her son-in-law Thomas St. Leger? Laynesmith claims that "this rather suggests that Richard's own piety was not consciously influenced by hers", and sure, that seems obvious, but it certainly can't have been the only reason. Was she merely overlooked (unlikely), or did they have a quarrel at the time, or was it for another now-unknown reason? Whatever the case, it's a small but intriguing detail to me.

Sources:

"Cecily, Duchess of York" by J.L. Laynesmith

"A Paper Crown: The Titles and Seals of Cecily, Duchess of York" by J.L. Laynesmith (The Ricardian)

"Cecily Neville: Mother of Kings" by Amy License

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Met Gala attendees should be slaughtered en masse like aristocrats at the Battle of Towton.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

IMAGENES Y DATOS INTERESANTES DEL DIA 29 DE MARZO DE 2024

Viernes Santo, Año Internacional de los Camélidos.

San Segundo, Santa Catalina y Santa Derfuta.

Tal día como hoy en el año 1983

En Alemania Federal, el demócrata cristiano Helmut Kohl, se convierte en canciller, esta vez avalado por las urnas, al ganar su partido las elecciones. Kohl ya era canciller desde el 1 de octubre del año pasado, fecha en la que fue investido tras haber llegado a un acuerdo con el FPD para presentar conjuntamente una moción de censura contra Helmut Schmidt y formar un gobierno de coalición. (Hace 41 años)

1973

'Tras diez años de combates, Estados Unidos completa la retirada de su ejército de Vietnam. El saldo en vidas de esta terrible guerra es de 500.000 civiles y 200.000 soldados vietnamitas por 57.000 soldados norteamericanos. Otra consecuencia ha sido la profunda división en la sociedad estadounidense. Además, de las arcas americanas han tenido que salir, en todos los conceptos, cerca de 300.000 millones de dólares para sufragar la contienda e impedir que Vietnam del Sur cayese en manos comunistas. La guerra proseguirá hasta que la toma de Saigón en 1975 fuerce la rendición incondicional de las tropas survietnamitas y la unificación del país, bajo el control del gobierno comunista de Vietnam del Norte. (Hace 51 años)

1962

En Argentina, las Fuerzas Armadas confinan en la isla Martín García al presidente Arturo Frondizi. Anulan las elecciones y designan a José María Guido, presidente del Senado, para ocupar la presidencia a fin de mantener una imagen de gobierno civil. (Hace 62 años)

1847

El general norteamericano Winfield Scott arrebata a los mexicanos el puerto de Veracruz, tras siete días de férreo asedio e intenso bombardeo. Después de esta derrota, se librarán duras batallas en las localidades de Cerro Gordo, Padierna, Churubusco y Molino del Rey, tras las cuales México perderá Texas, Arizona, Nuevo México y la Alta California. (Hace 177 años)

1638

En América del Norte, colonos suecos, comandados por el explorador Peter Minuit, fundan su primer asentamiento en Delaware, al que llaman Nueva Suecia al erigir el Fuerte Cristina (en honor a la reina sueca) cerca del lugar donde hoy se encuentra la ciudad de Wilmington. La Nueva Suecia estará formada por varios cientos de colonos suecos y finlandeses, que más adelante tendrán problemas entre sí. En 1643, el recién nombrado gobernador sueco Johan Bjornsson mandará construir nuevos emplazamientos en Varkenskill, Upland y Nueva Cristina, mientras los pastores luteranos se dedicarán a la tarea de evangelizar a los indios. (Hace 386 años)

1549

Thomé de Souza, militar y político portugués, funda la ciudad de Salvador de Bahía, primera capital de Brasil y una de las ciudades más antiguas del país y centro administrativo y religioso de las colonias portuguesas en América hasta 1763, año en que se trasladará la capitalidad a la localidad de Río de Janeiro. (Hace 475 años)

1461

En Inglaterra, durante la Guerra de las Dos Rosas (asi llamada porque cada casa tenía una rosa representativa, la de Lancaster era de color rojo, mientras que la de Yorkshire era de color blanco), tiene lugar la Batalla de Towton, una de las más grandes y cruenta en territorio inglés, en la que las tropas comandadas por Eduardo de York, vencen al ejército lancasteriano de la Reina Margarita, convirtiéndose en el Rey Eduardo IV de Inglaterra que mandará perseguir y matar a los derrotados. La Reina Margarita y su esposo Enrique de Lancaster, se refugiarán temporalmente en Escocia. (Hace 563 años)

1430

El Imperio Otomano bajo las órdenes del sultán Murad II, inicia un asedio de tres días a la ciudad de Tesalónica (Grecia), que concluirá con la conquista de la urbe y la captura de 7.000 de sus habitantes para ser utilizados como esclavos. En 1492, cuando los judíos sefardíes sean expulsados de España por los Reyes Católicos, esta localidad les acogerá bien. De este modo, la ciudad se enriquecerá y gozará de un gran desarrollo económico que alcanzará su cima en los siglos XVIII y XIX. (Hace 594 años)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Simon Ghost Riley

Demon name: Ymeo Sgosh Inirlt

Birth: Battle of Towton... War of the Roses.

*Sounds like a knight conflict* -Demonologist [REDACTED]

*Calls himself the ghost of chivalry* -Demonologist [REDACTED]

Notable feature: Favors knives and swords compared to the typical axes or whips other bloodthirsters carry. He is very talkative which aligns with his habit of targeting imperial knights when summoned. Like König he is black furred/skinned though there is a face marking that looks like a human skull around his eyes and upper face. His horns tend to spiral. -Demonologist [REDACTED]

"Luv what has two legs and bleeds?"

"What?" -Handler [REDACTED]

"Half a Dog."

[Snickering in the background] "Do not laugh at the Demonhost's joke!"

*I'm pretty sure the Demonhost was lobotomized so I think the demon was making a joke? Are you sure you gave me a Khornite demon to watch?* -Handler [REDACTED]

Demonhost: Has to be 2+ meters tall or else the skin of the demonhost starts to rip. He will complain about the skin being too tight and if too small it will rip fully. Noted to like to keep it's face covered so often a baclava will be given to him to wear but usually even with this he has a habit of putting the front part of a human skull on his face (upper jaw to just a little bit above the brow line). Has a nasty habit of getting his host killed so two handlers are needed or Jocnr has to order him. Hair tends to shift to brown or blonde and either brown eyes or blue eyes it all depends on the host. He is one of the few who is very picky about the initial hair and eye color; Age should be no older than 35. His left arm has to be left unmarked as usually tattoo like markings will show up and replace anything that is there. Will keep his hair short in standard Astra Militarum standards.

Will want to be paired up with Imvaassj (Soap) if possible as the two seem to enjoy talking. He's a very talkative and as some initiates point out "silly" man. Telling bad jokes and has a strange taste in clothing as some initiate got them a pair of gloves with bones on them and he has since demanded that it be offered to him each time he inhabits a new host that they have to have those gloves.

Bonds to initiates easily as well as Agents working along side him but will be trouble for authority as he will obey his orders but barely. Has a strict code of honor and will take slights against his honor with the same intensity as a knight pilot would.

@ghouljams for your regency aus (and your König stuff too)

and to all the other knight ghost girlies who helped inspire this.

@charliemwrites I'm not gonna lie there's a bit of your charmed slasher somewhere in this demon man

#simon ghost riley#demon!ghost#demon!simon ghost riley#bloodthirster#bloodthirster!ghost#cod 141#task force 141#warhammer 40k#chivalrous ghost#chivalrous simon ghost riley

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Random British Royal tidbits

I'm reading "The Vanity Fair Diaries" by Tina Brown and came across this tidbit:

Monday May 26, 1986

"We had lunch with the preposterous Princess Michael of Kent, who looked about fifteen hands high in an orange silk wrap dress. She has developed a mad, false laugh and a new Lady Bracknell voice for dealing with inferiors. "Row-eena," she gushed at the cowed debutante she totes around as her "lady in waiting." "where is the Dom Perignon? It was sitting outside but those fooooools have taken it away! Find it!" (Mad false laugh.) "Isn't the service quite diabolical? Do shut the kitchen door, Rowena. I hate to stare into a kitchen!"

From The Vanity Fair Diaries by Tina Brown, p. 199

Princess Michael of Kent, nee' Baroness Marie-Christine Anna Agnes Hedwig Ida von Reibnitz, would have been 41 at the time of this lunch. She was born in the German-occupied Sudetenland in what is now the Czech Republic. Her father, Baron Günther Hubertus von Reibnitz, was a descendant of the ancient Reibnitz family, Silesian landowners, who trace their ancestry back to 1288. He was a Nazi party member and a SS calvary officer during WWII.

Princess Michael's mother was Countess Maria Anna Carolina Franziska Walburga Bernadette Szapary von Muraszombath, Szechysziget und Szapar. The House of Szapáry is an old and important Hungarian noble family. Members of this family held the title of Imperial Count granted to them on 28 December 1722 by Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor.

Princess Michael's parents divorced n 1948 and she with her mother and eldest brother moved to Rose Bay, Australia. In the early 1960s, she lived with her father on his farm in Mozambique. She then went from Vienna to London to study History of Fine and Decorative Art at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

She first married an English banker in 1971, but divorced in 1977. Once month after her marriage was annulled by the Pope, she married Prince Michael of Kent, Queen Elizabeth II's first cousin. She has said that Lord Mountbatten played matchmaker.

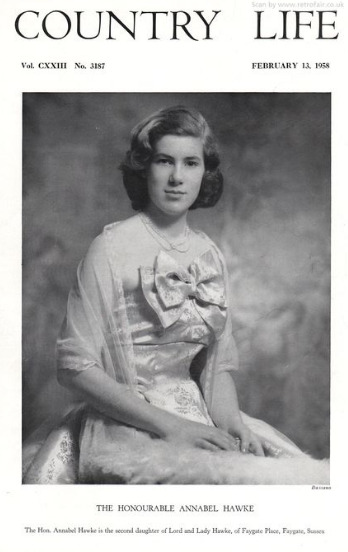

The lady-in-waiting mentioned in the excerpt is The Hon. Rowena Hawke Leatham Sanders, daughter of the 9th Baron Hawke of Towton.

The Baron of Towton peerage title was created on 20 May 1776 for the admiral Sir Edward Hawke (of Scarthingwell Hall in the parish of Towton), responsible for a blockade of all French merchant shipping and the grounding of six French ships, and scattering of the rest, at the Battle of Quiberon Bay.

Rowena Hawke's sister, Annabel, pictured above.

Rowena's father, Bladen Wilmer Hawke, 9th Baron of Towton, above. He served as a Lord-in-waiting (government whip in the House of Lords from 1953 to 1957 in the Conservative administrations of Churchill, Eden and MacMillan.

Another of Rowena's sisters, Lavinia, married Nicholas MacLean-Bristol. She became a Justice of the Peace and lives in 15th century Old Breachacha Castle on the Isle of Coll in Scotland. This tower fortress was the stronghold of the MacLean clan. The Isle of Coll was granted to the MacLeans in 1431. There is also a new "castle" on this island, built in 1750, which is available to rent for just £1500 for a party of two for one week.

Rowena lives at Hankerton Priory, Malmesbury, Wiltshire, and borrowed a page from her sister's notebook, as her home is also available as an Air BNB rental - hosted by Rowena! Perhaps she will tell you stories about her days with Princess Michael if you stay with her?

https://www.airbnb.com/rooms/2777181?source_impression_id=p3_1676477115_Gba9bnmOeznlt0af

#princess michael#tina brown#Vanity Fair Diaries#Rowena Hawk#British peerage#british royal family#wiltshire#malmesbury

18 notes

·

View notes