#henry walthall

Text

Then this ebony bird beguiling my sad fancy into smiling,

By the grave and stern decorum of the countenance it wore,

"Though thy crest be shorn and shaven, thou," I said, "art sure no craven,

Ghastly grim and ancient Raven wandering from the Nightly shore—

Tell me what thy lordly name is on the Night's Plutonian shore!"

Quoth the Raven "Nevermore."

3 notes

·

View notes

Audio

The infamous lost film arrives on the podcast with September's bonus horror adjacent episode.

This month we watch a reconstruction of Tod Browning's LONDON AFTER MIDNIGHT (1927) by producer Rick Schmidlin! The film stars Man of a Thousand Faces Lon Chaney in one of his most iconic disguises.

#podcast#london after midnight#mgm#metro goldwyn mayer#tod browning#lon chaney#irving thalberg#waldemar young#josegh w farnham#the hypnotist#marceline day#conrad nagel#henry walthall#polly moran#edna tichenor#claude king#merrit gerstad#tcm#rick schmidlin#lost film#horror adjacent#bonus episode

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ford Sterling and Phyllis Haver / Mrs. Ford Sterling and Henry B. Walthall

#ford sterling#phyllis haver#teddy sampson#henry b. walthall#henry walthall#국가의 탄생 1915#hearts and flowers 1919#fordphyllis forever

0 notes

Text

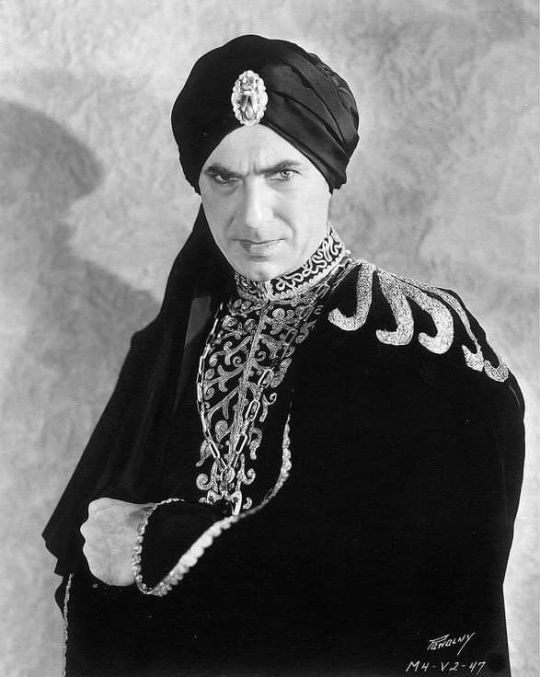

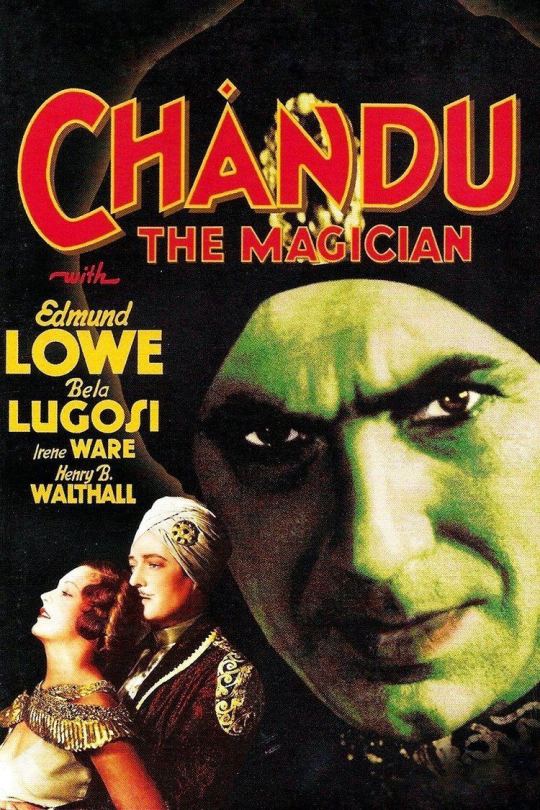

Chandu the Magician 1932

Roxor (Lugosi) kidnaps Robert Regent and his death ray invention. He hopes to degenerate humanity into mindless brutes, leaving himself as Earth's supreme intelligence.

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Birth of a Nation (D.W. Griffith, 1914)

#the birth of a nation#d.w. griffith#d. w. griffith#griffith#henry b. walthall#lillian gish#dog#gif#dove#1914#silent film#silent movies#silent cinema#silent

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

WINGS 1927

Jack - don't you know me?

#wings#1927#clara bow#charles rogers#richard arlen#jobyna ralston#el brendel#richard tucker#gary cooper#gunboat smith#henry b. walthall

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

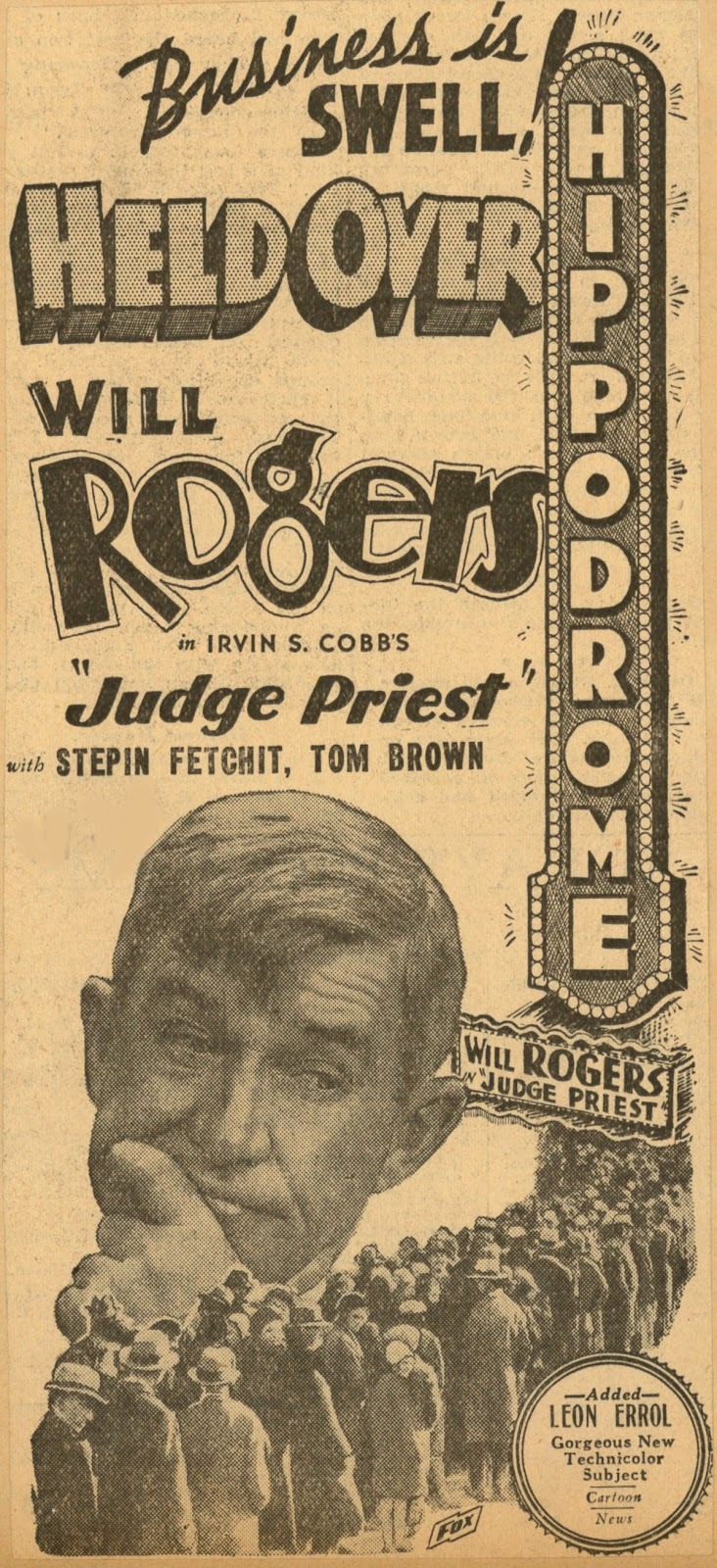

Judge Priest (1934) John Ford

December 14th 2023

#judge priest#1934#john ford#will rogers#tom brown#anita louise#stepin fetchit#henry b. walthall#david landau#hattie mcdaniel#charley grapewin#berton churchill#rochelle hudson#brenda fowler#frank melton#old judge priest

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Avenging Conscience: or 'Thou Shalt Not Kill' (D.W. Griffith, 1914)

#the avenging conscience: or 'thou shalt not kill'#d.w. griffith#griffith#d. w. griffith#silent film#1914#gif#silent movies#silent cinema#silent#blanche sweet#henry b. walthall#the avenging conscience#edgar allan poe

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

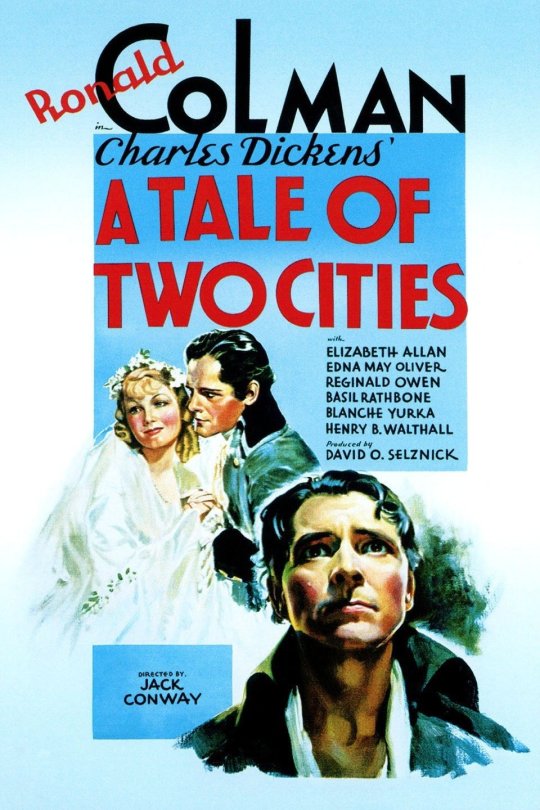

#a tale of two cities#ronald colman#elizabeth allan#edna may oliver#reginald owen#basil rathbone#blanche yurka#henry b. walthall#jack conway#1935

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mae Marsh-Henri B. Walthall "El nacimiento de una nación" (The birt of a nation) 1915, de D. W. Griffith.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

The Murder in the Museum (1934)

My rating: 4/10

Dull and unremarkable, and for a movie set at a sideshow bizarrely devoid of any kind of music (seriously, there's actual dance scenes set entirely to crowd noises), but ultimately, I suppose, inoffensive.

#The Murder in the Museum#Melville Shyer#F.B. Crosswhite#Henry B. Walthall#John Harron#Phyllis Barrington#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

Home, Sweet Home (1914, D.W. Griffith)

#home sweet home 1914#d.w. griffith#dorothy gish#lillian gish#henry walthall#henry b. walthall#favorite scene#really cute dorothy#i adore you mr. walthall

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

17 giugno … ricordiamo …

17 giugno … ricordiamo …

#semprevivineiricordi #nomidaricordare #personaggiimportanti #perfettamentechic

2019: Gloria Vanderbilt, Gloria Laura Vanderbilt, è stata una stilista, scrittrice, attrice ed ereditiera statunitense, membro della ricca famiglia Vanderbilt di New York. (n. 1924)

2017: Anneliese Uhlig, attrice e giornalista tedesca, naturalizzata statunitense. (n. 1918)

2017: Venus Ramey, modella statunitense, eletta Miss Distretto di Columbia ed in seguito Miss America 1944. . (n. 1924)

2016:…

View On WordPress

#17 giugno#17 giugno morti#Anneliese Uhlig#Armilda Jane Owen#Big Grey#Bob Williams#Carllyle Blackwell#Carlyle Blackwell#Cyd Charisse#Davey Lee#Edmond Roudnitska#Ellen Schwanneke#Gale Henry#Gianfranco Ferrè#Gloria Laura Vanderbilt#Gloria Vanderbilt#Harry Weedon#Henri Vidon#Henry B. Walthall#Henry Beckerman#Henry Beckman#Henry Brazeale Walthall#Henry Vidon#Jean Brochard#Louis Van Rooten#Luis Van Rooten#Marvel Luciel Rea#Marvel Rea#Olinto Cristina#Pamela Britton

0 notes

Text

The Birth of a Nation (D.W. Griffith, 1915)

Cast: Lillian Gish, Mae Marsh, Henry B. Walthall, Miriam Cooper, Mary Alden, Ralph Lewis, George Siegmann, Walter Long, Robert Harron, Wallace Reid, Joseph Henabery, Elmer Clifton, Josephine Crowell, Spottiswoode Aitken, George Beranger, Maxfield Stanley, Jennie Lee, Donald Crisp, Howard Gaye, Raoul Walsh. Screenplay: Thomas Dixon Jr., D.W. Griffith, Frank E. Woods, based on a novel and play by Dixon. Cinematography: G.W. Bitzer. Film editing: D.W. Griffith, Joseph Henabery, James Smith, Rose Smith, Raoul Walsh.

Is it an overstatement to say that the stench of The Birth of a Nation is more than a subset of the blight cast on American society and politics by slavery? Because Griffith's film informed an entire industry, not only with its undeniable influence on the language and grammar of film, but also in the tendency to valorize bigness above intimacy, action over thought, sensation over understanding that has characterized the mainstream of American movies. It was the first blockbuster. It was both intelligently crafted and abominably stupid. It just might be the most pernicious work of art ever made, a magnificent nauseating lie. Its portrait of Reconstruction warped the teaching of history for generations, and although the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan that it inspired has waned, we still find ourselves swatting down the heirs of the Klan like the Proud Boys, the Promise Keepers, and others who would defend what one of Griffith's title cards calls the "Aryan birthright." Even the reaction against The Birth of a Nation has its dark side: The recognition of the power of movies that followed its release eventually produced calls for censorship that would hamstring the medium. On the right, a suspicion that movies had the power to promote a leftist agenda led to the blacklist era, in which communists, not racists, were the target. And what is the crusade by some against "wokeness" in the media but another call for the kind of ideological purity that would stifle art? So to call The Birth of a Nation an essential film is an understatement. Looking at it as a demonstration of the ability of cinema to profoundly affect society could reveal it to be the most important movie ever made.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

London After Midnight (also marketed as The Hypnotist) is a lost 1927 American silent-era mystery-thriller pseudo-vampire film that collectors now consider the 'holy grail' of lost films—directed and co-produced by Tod Browning and starring Lon Chaney, with Marceline Day, Conrad Nagel, Henry B. Walthall and Polly Moran. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer distributed the film.

The last known copy was destroyed in the 1965 MGM vault fire, along with hundreds of other rare early films, making it for decades one of the most sought-after lost films of the silent era. In 2002, Turner Classic Movies aired a reconstructed version, produced by Rick Schmidlin, who used the original script and film stills to recreate the original plot.

In May 2022, there were attempts to find a copy of the film in Australia, which was at the end of the film distribution chain.

#lost film#lost films#lost movie#lost movies#mystery#thriller#silent era#lon chaney#vampire#decade: 1920s#1920s film#1920s

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

American Culture in the 1910s: The Birth of a Nation (1915)

“If there is one film that stands at the centre of the interrelated developments in the economics, audiences, and the technical and narrative structures of film at this time, it is David Wark Griffith’s Civil War epic of 1915. Civil War pictures enjoyed a vogue in the 1910s, especially in the key fiftieth anniversary years of 1911, 1913 and 1915; ninety-eight such films were produced in 1913 alone.

Griffith, a Kentuckian and the son of a Confederate veteran, had bought the rights to Thomas Dixon’s The Clansman (1905), a successful novel and play which related how the Ku Klux Klan saved the white South from the supposed tyranny of black enfranchisement under radical reconstruction.

(In a deal which contemporary novelists would swoon over, Dixon was paid $2,500 up front for the film rights, and received 25 percent of the profits). Such a sweeping historical project suited Griffith’s enormous ambitions for film; he had chafed at the restrictions at Biograph where, between 1907 and 1913, he had built the studio’s preeminent reputation for quality films with an astonishing and technically innovative body of work.

Indeed, Biograph’s refusal to release Judith of Bethulia, his 1913 epic, partly because he had exceeded their length and budget restrictions without permission, prompted his resignation and signing with Mutual on the agreement that he could make two ‘special’ films per year.

His first was The Birth of a Nation. Costing an unprecedented $60,000 to produce, and an almost equal amount in promotion and legal fees, Griffith’s twelve-reel film was the most costly, lengthy and expensive to see in cinema history up to that time. It was also by far the most successful: by the end of 1917 it had grossed sixty million dollars. The film dramatised the fates of two families, one from South Carolina, one from Pennsylvania, in the years surrounding the Civil War.

The Southern Cameron family, headed by ‘Little Colonel’ Ben Cameron (Henry Walthall), are friendly with the northern Stoneman family, headed by Austin Stoneman (Ralph Lewis), the leader of the Republicans in the House of Representatives. Stoneman – modelled on the proponent of radical reconstruction, Thaddeus Stevens – is portrayed as possessing a variety of disastrous personal weaknesses, including vanity (he wears a wig), a fondness for bombast and, most pointedly, a predilection for his mulatto housekeeper, played by Mary Alden.

Following the war, and the deaths of sons from both families as well as an elaborately staged reconstruction of Lincoln’s assassination at Ford’s Theatre, Stoneman pursues a policy (to quote from Woodrow Wilson’s history of the period, which was used in many intertitles) designed to ‘put the white South under the heel of the black South’. To enforce this he ensures the appointment of Silas Lynch (George Siegmann), his mulatto henchman, as Lieutenant Governor of South Carolina.

Meanwhile, Ben Cameron – recuperating in a northern hospital after heroic deeds on the battlefield – has fallen for Elsie Stoneman (Lillian Gish) who is working as a nurse there. The remainder of the film dramatises the threat to white southerners of this political policy, a threat continually dramatised in sexual terms as black men attempt to rape members of both the Stoneman and the Cameron families. The film’s climax comes as Cameron devises the idea of the Klan, which is hailed as ‘the organization that saved the South from the anarchy of black rule’.

Riding to the rescue at the head of a huge posse of Klansmen, in scenes which had white audiences cheering, Cameron saves his sweetheart Elsie from the clutches of Lynch, and his sister from a horde of black militia. The double marriage at the close of the film sees ‘the former enemies of North and South . . . united again in common defence of their Aryan birthright’. Controversy attended this unvarnished white supremacist propaganda from the start. The National Board of Censorship voted fifteen to eight to pass the film, after insisting on cuts (such as a scene depicting the castration of the most malignant black rapist, Gus, and one showing ‘Lincoln’s solution’ of transporting black Americans back to Africa).

Riots broke out at screenings in Boston and Philadelphia, and the film was denied a release in several major cities. Moreover, the film was a major prompt to the formation of the second Ku Klux Klan in 1915 by William Simmons, a Methodist minister in Georgia. In the 1920s, the Klan would be a major political force for racism, anti-Semitism, anti-Catholicism and nativism, as its numbers swelled to over four million.

Conversely, the film gave a great boost to the national profile of the recently formed National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, which led a vigorous protest against the film aided by many sections of the liberal and Progressive media (Francis Hackett in the fledgling New Republic denounced it as ‘aggressively vicious and defamatory’; James Weldon Johnson saw Dixon’s attitude as one of ‘unreasoning hate’). Stung by such criticism, Griffith and Dixon mounted very public defences of the film’s historical accuracy and the principles of free speech in films, a publicity which adroitly fuelled the film’s notoriety and its box office returns.

One of the things which troubled critics most was the film’s astonishing technical virtuosity. ‘As a spectacle it is stupendous’, Hackett noted glumly, a feature which only added to its persuasiveness and ideological force. Indeed, critics who attempt to separate the film’s politics from its technical achievements often overlook the fact that it was precisely these technical achievements that gave those politics both an appeal and a legitimacy to millions of Americans.

The war scenes are epic in scale; and the final ride of the Klan, using tracking shots, dramatic high camera angles, and fast-paced cross-cutting between three different locations, was the apogee of a technique which Griffith had perfected at Biograph (where, as Tom Gunning notes, he had frequently utilised the ‘archetypal drama of a threatened bourgeois household’).

Scenes such as the final ball before the Confederate volunteers leave for war – lit strongly from above and behind, to give the characters a glow suggestive of the imminent destruction of a way of life – are beautifully composed; and, as Eileen Bowser notes, the scene of the Little Colonel’s homecoming, where the camera withdraws its omniscience at the moment he enters his home and his mother’s arms, has an undimmed emotive power.

Yet, like the popular fiction of the era such as Tarzan of the Apes, the popularity of The Birth of a Nation must be partly ascribed to its indulgence of fantasies of sexual dominance. Griffith had even swapped Lillian Gish into the lead role of Elsie Stoneman in place of Blanche Sweet because – as Gish recalled – ‘I was very blonde and fragile-looking. The contrast with the dark man [a blacked-up George Siegmann] evidently pleased Mr. Griffith, for he said in front of everyone, “Maybe she would be more effective than the mature figure I had in mind.”’

A turning point in assessments of the aesthetic and economic potential of features, nonetheless the film’s ability to represent and market with such wild success such a disturbing and reactionary conjunction of race, gender and sexuality is one of the decade’s most disturbing cultural moments.”

- Mark Whalan, “Film and Vaudeville.” in American Culture in the 1910s

5 notes

·

View notes