#herman j. mankiewicz

Text

Orson Welles seated on witness stand at trial of Herman J. Mankiewicz in Los Angeles, Calif., 1943

#your honor my friend is literally a traumatized neurodivergent 45 year old minor who drunk drives to cope#orson welles#herman j. mankiewicz

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

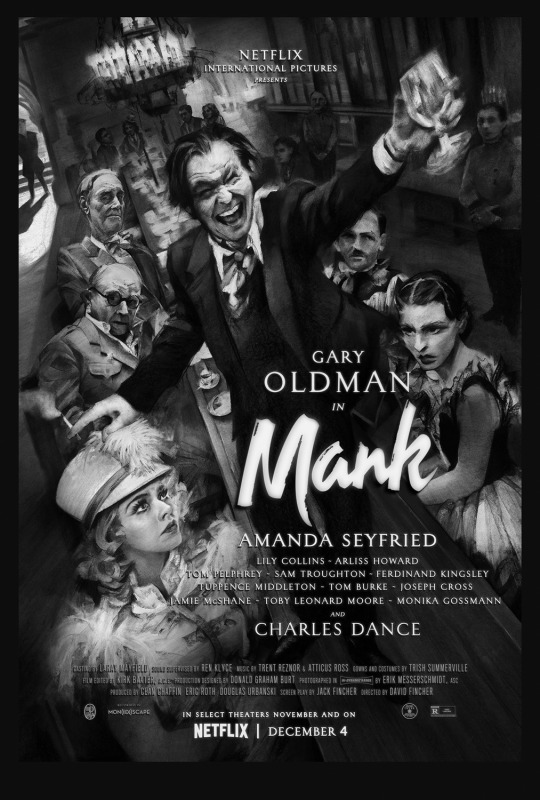

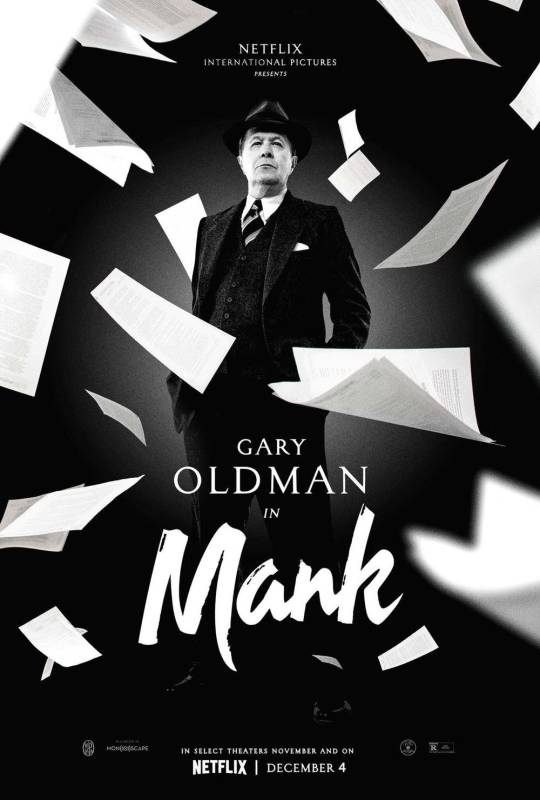

What I’m watching (2024 Edition) || Mank (2020)

#mank#watching#watching24#Herman J. Mankiewicz#Gary Oldman#amanda seyfried#marion davies#fav actors#netflix#David Fincher

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Best Best Original Screenplay Tournament, Round 3/Elite 8

Just like the upcoming Tonys will be, our little bracket isn't scripted (ain't no scabs here!). But we're still offering plenty of drama, like Dog Day Afternoon's upset over top-seed Pulp Fiction, or The Usual Suspects pulling ahead of Everything Everywhere All At Once in a tight contest!

What will happen in Round 3? Your votes decide!

All polls live for one week. Bracket seeded by IMDb rating.

#best best original screenplay tournament#oscars#academy awards#best original screenplay#dog day afternoon#frank pierson#parasite#bong joon ho#han jin won#citizen kane#orson welles#herman j. mankiewicz#thelma & louise#thelma and louise#callie khouri#fargo#coen brothers#joel coen#ethan coen#the usual suspects#christoper mcquarrie#sunset boulevard#sunset blvd#billy wilder#charles brackett#d.m. marshman jr#get out#jordan peele#poll#polls

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Herman J. Mankiewicz (November 7, 1897 – March 5, 1953) ✍️

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Citizen Kane (1941)

My rating: 8/10

Still one of the most compelling movies about an utterly pathetic asshole ever made. I mean. The writing in this thing alone, holy shit.

#Citizen Kane#Orson Welles#Herman J. Mankiewicz#John Houseman#Joseph Cotten#Dorothy Comingore#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

David Finchers kunstvoll verschachteltete Filmbiographie über den berühmten, aber etwas anstrengenden und für das Studiosystem zu direkt seine Meinung mitteilenden Drehbuchautor Herman J. Mankiewicz bei der Arbeit am seinem kunstvoll verschachtelten Drehbuch zu Citizen Kane ist nicht der typische David-Fincher-Film. Das erklärt möglicherweise die Enttäuschung, die gelegentlich darüber geäußert wird, dabei ist er recht großartig. Das Drehbuch hat sein verstorbener Vater schon vor Jahrzehnten geschreiben, es setzt ein wenig Grundwissen voraus, zeigt aber schön, wie es dazu kam, daß Mank sich so auf William Randolph Hearst einschoss (Marion Davies hingegen war nie gemeint) und ist insofern etwas kontrovers, als Orson Welles hier einmal nicht als das allumfassende Allround-Genie herüberkommt, aber in Zeiten, wo das wieder erstarkende Studiosystem sich aufführt, als brauche es eigentlich gar keine Drehbuchautoren mehr, vielleicht auch ein nützlicher Hinweis. Außerdem bietet es -wie wir es nicht anders erwarten- einmal mehr eine große Gary-Oldman-Show, für die es sich eigentlich auch schon lohnen würde. So vorbereitet können wir jetzt auch mal wieder Citizen Kane anschauen.

#Mank#Gary Oldman#Amanda Seyfried#Charles Dance#Joseph Cross#Lily Collins#Tuppence Middleton#Film gesehen#David Fincher#Herman J. Mankiewicz#Citizen Kane#Orson Welles

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Last Command (1928)

Before their professional rupture while making The Blue Angel (1930), both Josef von Sternberg and Emil Jannings came from German-speaking environments to find success in Hollywood. But while von Sternberg’s family emigrated to the United States from Austria in his teenage years, Jannings carved out a reputation of playing larger-than-life protagonists in Universum-Film AG (UFA) films such as F.W. Murnau’s The Last Laugh (1924) and Faust (1926). His rising star spurred Paramount to offer Jannings a short-term contract that lasted two-and-a-half years and six features. Of Jannings’ extant movies at Paramount*, The Last Command is the one that has brought the most acclaim.

We open in 1928 Hollywood. While shooting a Russian Revolution picture, Russian expatriate director Leo Andreyev (an underutilized William Powell) selects Sergius Alexander (Jannings; whose character is living in poverty and takes jobs as a Hollywood extra) out of a heap of casting photos. Leo’s decision to cast Sergius is less magnanimous than it first appears to be, but to say more would be to spoil the ending. While in the dressing room, Sergius reminisces about events a decade prior. Flash back to 1917 Imperial Russia. Grand Duke Sergius Alexander, cousin of the Tsar, Commanding General of the Russian Armies (for students of Russian history and politics, this is analogous to “Chief of the General Staff”), is commanding the tsarist troops to battle Bolshevik revolutionaries. Informed that two actors entertaining his soldiers are actually Bolshevik agents, he orders that they be ushered into his office so that he might humiliate them. Sergius has his way with one of the agents, Leo Andreyev. But for Natalie Dabrova (Evelyn Brent), Sergius finds himself attracted to her. Despite the dangers involved, he keeps Natalie by his side. Revolutionary zeal and Stockholm syndrome be damned, they fall in love. The film will conclude when it flashes back to 1928 Hollywood.

Jack Raymond (later a director of films such as 1930’s The Great Game) plays a brief role as Leo’s conceited Assistant Director.

The circumstances and developments surrounding Sergius and Natalie’s romance is far-fetched and contrived beyond belief. Natalie’s reasons for falling for Sergius – paraphrasing her, that she could never believe that someone could love Russia as much as he – are unintentional comedic gold. The film’s best line appears as Sergius realizes that Natalie is not going to act on her revolutionary beliefs to assassinate him: “From now on you are my prisoner of war – and my prisoner of love.” All credit to intertitle writer Herman J. Mankiewicz (1941’s Citizen Kane, 1942’s The Pride of the Yankees) for that screamer of a line. Whatever political differences between the two main characters melts away because of that.

This writing from journeyman screenwriter John F. Goodrich (1933’s Deluge, 1936’s Crack-Up) and the story from Lajos Bíró (1933’s The Private Life of Henry VIII,1940’s The Thief of Bagdad) points to a larger problem regarding the film’s political depictions. Never mind the ideological chasm that exists between a man sworn to uphold the tsarist establishment and a woman to whom that very establishment is the embodiment of all that she and her comrades find loathsome. The Last Command, in keeping with Western attitudes towards the Bolsheviks, is decidedly sympathetic towards Imperial Russia, rather than the inebriated, murder-hungry proletariat mob that wants nothing but bloodshed. There is no political nuance to these depictions. Tsarist Russia is honorable, the unquestionably legitimate state; the Bolsheviks’ demands flattened to simply mindless violence for the sake of it. This is not to deny the facts that there were decent people serving the Tsar nor that the Bolsheviks engaged in excessive violence, but that the film overly simplifies the conditions in 1917 Russia.

Despite his status as one of the most accomplished Hollywood directors working during the transition from silent film to synchronized sound, Josef von Sternberg disdained the Studio System and producer control over filmmaking (if only he was alive to see how things are today!). In The Last Command’s bookending scenes in 1928 Hollywood, von Sternberg takes aim squarely at Hollywood norms. Note the arrogance in which the Assistant Director conducts himself in front of all the extras. How infuriating it must be for the audience when he chastises the elderly Sergius for correcting him about a detail on a Russian general’s uniform: “I’ve made twenty Russian pictures. You can’t tell me anything about Russia!” Filmmaking in this environment, according to The Last Command, is exploitative. There is little to no regard about the wellbeing of all the extras scraping by with a meager day’s wages. As for Leo’s intentions for Sergius, the psychological cruelty in which he directs him is something he may or may not come to regret in the film’s final seconds. In those closing shots, the Assistant Director’s pithy remark encapsulates Hollywood’s wanton disregard for those uncredited many who wove themselves into the magical fabric of Old Hollywood.

The film’s most narratively crucial scenes – excluding the romantic scenes between Sergius and Natalie – make excellent use of extras and the blocking of extras. Whether it is the scene where the Bolsheviks drag Sergius off the train and threaten to hang and mutilate him or the film’s final scene on the studio soundstage, there is a bustling of activity in the background. Von Sternberg and cinematographer Bert Glennon (1939’s Stagecoach and Drums Along the Mohawk) vivify The Last Command with these masses of people. Look at the furious, grasping hands as Sergius as the Bolsheviks tear his outer layers off in the cold – this might not approach the violence of Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925), but that is because the anger here is directed at a solitary figure. The crew behind the camera and the extras reacting organically to Sergius’ acting adds to Jannings’ memorable performance in the climax, empowering a scene very obviously shot on a soundstage.

Somehow, these critical framing scenes from The Last Command escaped the attention of Paramount executives during the film’s production. When learning about them only after seeing the final product, they planned to prevent the film’s release. Also citing von Sternberg’s portrayal of the Russian Revolution (including portraits of Stalin and Trotsky), Paramount’s executives only relented when an unnamed Paramount stockholder compelled them to release The Last Command.

In spite of the questionable central romance and its poor historical representations, The Last Command thrives due to Jannings’ performance. Paramount wanted Jannings for this role due to his reputation as a theatrical, bombastic actor. He does not disappoint here. Taking a page from his performance in The Last Laugh, Jannings’ character similarly takes pride in an article of clothing. Where in The Last Laugh he loses his doorman’s uniform, Jannings regains a general’s uniform in The Last Command. With it, an utterly broken man finds a modicum of self-respect (at the very least), or perhaps it resurfaces the jingoist that once was. The physical transformation and mental turn Jannings embodies is absolutely compelling and deeply tragic. Art then begins to replicate the past too faithfully. Man and character become the same. Jannings won the inaugural Academy Award for Best Actor for The Last Command and The Way of All Flesh (1927)‡, despite German Shepherd Rin Tin Tin (1922’s The Man from Hell’s River, 1925’s The Clash of the Wolves) receiving the most votes in the category. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS), wishing to be taken seriously and not wanting to bestow the inaugural Best Actor statue to a dog, gave the award to the runner-up, Jannings.

Back in Weimar Germany, Jannings and von Sternberg would work together on The Blue Angel (1930) – their finest collaboration with each other. But the two clashed repeatedly while making The Blue Angel, mostly over von Sternberg’s fawning over Marlene Dietrich during production. Von Sternberg returned to America and remained with Paramount until 1935, and his Hollywood standing rose alongside Marlene Dietrich's. Following the end of that contract, he bounced around various Hollywood studios, never again finding the cinematic footing he had while at Paramount. By contrast, Jannings remains in the German film industry following The Blue Angel and starred in several Nazi propaganda films that, after the end of World War II, made him unemployable.

As if foreshadowing Sunset Boulevard (1950), The Bad and the Beautiful (1952), and even Singin’ in the Rain (1952), this dramatic unpackaging of Hollywood’s dark underbelly has elements of scathing satire that form the backbone of the its best moments. No matter the mutual accusations of imperiousness, Jannings and von Sternberg while on set of The Last Command, pieced together a film that obscures its true messaging beneath its ridiculous romance.

My rating: 8.5/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog. Half-points are always rounded down.

* The Way of All Flesh (1927), The Patriot (1928), and Street of Sin (1928) are lost; Sins of the Fathers (1928) is only rumored to be intact; and only The Last Command and Betrayal (1929) are extant.

‡ The 1st Academy Awards was the only ceremony in which actors and actresses were nominated for a body of work, rather than their work on an individual film.

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

#The Last Command#Josef von Sternberg#Emil Jannings#Evelyn Brent#William Powell#Jack Raymond#Nicholas Soussanin#Michael Visaroff#Fritz Feld#Lajos Bíró#John F. Goodrich#Herman J. Mankiewicz#Bert Glennon#William Shea#silent film#TCM#saveTCM#My Movie Odyssey

0 notes

Text

Stamboul Quest (1934)

Stamboul Quest by #SamWood starring #MyrnaLoy, "Loy is iconic, divine and has all the range for the part,"

SAM WOOD

Bil’s rating (out of 5): BBB

USA, 1934. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Story by Leo Birinsky, Screenplay by Herman J. Mankiewicz. Cinematography by James Wong Howe. Produced by Bernard H. Hyman, Sam Wood. Music by William Axt. Production Design by Cedric Gibbons. Costume Design by Dolly Tree. Film Editing by Hugh Wynn.

Myrna Loy sits in the courtyard of a convent looking breathtaking in a white…

View On WordPress

#Bernard H. Hyman#C. Henry Gordon#Cedric Gibbons#Dolly Tree#George Brent#Herman J. Mankiewicz#Hugh Wynn#James Wong Howe#Leo Birinsky#Lionel Atwill#Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer#Mischa Auer#Myrna Loy#Rudolph Anders#Sam Wood#William Axt

0 notes

Note

I saw on a Wikipedia list of things entering the public domain that Herman J. Mankiewicz's work enters the public domain. What does this mean for Citizen Kane, if it's not in the public domain now when do you think it'll be within the public domain?

In the US it becomes public domain in 2037.

So i think legally speaking it doesnt affect anything other than we are one year closer to it being public domain. Usually from a legal standpoint its not enough for just the screenplay to be public domain its usually treated as a package deal, so either all of it is public domain or none of it.

There are odd cases like It's a wonderful life where its based on a copyrighted book and the soundtrack was bought by republic in order to keep a hold of it because it lapsed into public domain as they realized how valuable it was.

Good question, hope this answers it for you

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Possibly the most famous telegram in Hollywood history was sent in 1925, when Herman J. Mankiewicz, the future co-writer of “Citizen Kane,” urged his newsman friend Ben Hecht to move West and collect three hundred dollars a week from Paramount. “The three hundred is peanuts,” Mankiewicz assured him. “Millions are to be grabbed out here and your only competition is idiots.” The rise of the talkies, for which Hecht became a prolific scenarist, soon brought a wave of non-idiot writers to Los Angeles, to supply the snappy movie dialogue of the thirties—a decade that, not incidentally, saw the rise of the Screen Writers Guild.

Writers have always endured indignities in Hollywood. But, as long as there are millions to be grabbed, the trade-off has been bearable—except when it isn’t. The past month has brought the discontent of television writers to a boiling point. In mid-April, the Writers Guild of America (the modern successor to the Screen Writers Guild) voted to authorize a strike, with a decisive 97.85 per cent in favor. The guild’s current contract with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers expires on May 1st; if the negotiations break down, it will be the W.G.A.’s first strike since late 2007 and early 2008. At issue are minimum fees, royalties, staffing requirements, and even the use of artificial intelligence in script production—but the over-all stakes, from the perspective of TV writers, feel seismic. “This is an existential fight for the future of the business of writing,” Laura Jacqmin, whose credits include Epix’s “Get Shorty” and Peacock’s “Joe vs. Carole,” told me; like the other writers I spoke to, she had voted for the strike authorization. “If we do not dig in now, there will be nothing to fight for in three years.” TV writers seem, on the whole, miserable. “The word I would use,” Jacqmin said, “is ‘desperation.’ ”

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

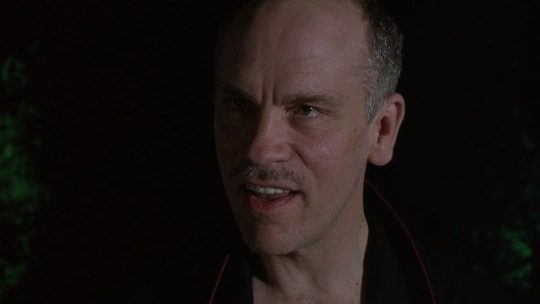

john malkovich as herman j. mankiewicz in rko 281

primetime emmy award nominee for outstanding supporting actor in a limited series or movie

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Title: Mank

Rating: R

Director: David Fincher

Cast: Gary Oldman, Amanda Seyfried, Lily Collins, Arliss Howard, Tom Pelphrey, Sam Troughton, Ferdinand Kingsley, Tuppence Middleton, Tom Burke, Joseph Cross, Jamie McShane, Toby Leonard Moore, Monika Gossmann, Charles Dance, Jack Romano, Adam Shapiro, John Churchill, Jeff Harms, Derek Petropolis, Sean Persaud, Paul Fox

Release year: 2020

Genres: history, drama

Blurb: 1930s Hollywood is reevaluated through the eyes of scathing social critic and alcoholic screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz as he races to finish the screenplay for Citizen Kane.

#mank#r#david fincher#gary oldman#amanda seyfried#lily collins#arliss howard#tom pelphrey#2020#history#drama

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Joseph Cotten, Orson Welles, and Everett Sloane in Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941)

Cast: Orson Welles, Joseph Cotten, Dorothy Comingore, Agnes Moorhead, Ruth Warrick, Ray Collins, Erskine Sanford, Everett Sloane, William Alland, Paul Stewart, George Coulouris. Screenplay: Orson Welles, Herman J. Mankiewicz. Cinematography: Gregg Toland. Art direction: Van Nest Polglase, Perry Ferguson. Film editing: Robert Wise. Music: Bernard Herrmann.

Things I don't like about Citizen Kane:

The "News on the March" montage. It's an efficient way of cluing the audience in to what it's about to see, but is it necessary? And was it necessary to make it a parody of "The March of Time" newsreel, down to the use of the Timespeak so deftly lampooned by Wolcott Gibbs ("Backward ran sentences until reeled the mind")?

Susan Alexander Kane. Not only did Orson Welles leave himself open to charges that he was caricaturing William Randolph Hearst's relationship with his mistress, Marion Davies, but he also unwittingly damaged Davies's lasting reputation as a skillful comic actress. We still read today that Susan Alexander (whose minor talent Kane exploits cruelly) is to be identified as Welles's portrait of Davies, when in fact Welles admired Davies's work. But beyond that, Susan (Dorothy Comingore) is an underwritten and inconsistent character -- at one point a sweet and trusting object of Kane's affections and later in the film a vituperative, illiterate shrew and still later a drunk. What was it in her that Kane initially saw? From the moment she first lunges at the high notes in "Una voce poco fa," it's clear to anyone, unless Kane is supposed to have a tin ear, that she has no future as an opera star. Does she exist in the film primarily to demonstrate Kane's arrogance of power? A related quibble: I find the portrayal of her exasperated Italian music teacher, Matiste (Fortunio Bonanova), a silly, intrusive bit of tired comic relief.

Rosebud. The most famous of all MacGuffins, the thing on which the plot of Citizen Kane depends. It's not just that the explanation of how it became so widely known as Kane's last word is so feeble -- was the sinister butler, Raymond (Paul Stewart) in the room when Kane died, as he seems to say? -- it's that the sled itself puts so much psychological weight on Kane's lost childhood, which we see only in the scenes of his squabbling parents (Agnes Moorehead and Harry Shannon). The defense insists that the emphasis on Rosebud is mistakenly put there by the eager press, and that the point is that we often try to explain the complexity of a life by seizing on the wrong thing. But that seems to me to burden the film with more message than it conveys.

And yet, and yet ... it's one of the great films. Its exploration of film technique, particularly by Gregg Toland's deep-focus photography, is breathtaking. Perry Ferguson's sets (though credited to RKO art department head Van Nest Polglase) loom magnificently over the action. Bernard Herrmann's score -- it was his first film -- is legendary. And it is certainly one of the great directing debuts in film history. But I don't think it's the greatest film ever made. In the top ten, maybe, but it seems to me artificial and mechanical in comparison to the depiction of actual human life in Tokyo Story (Yasujiro Ozu, 1953), the elevation of the gangster genre to incisive social and political critique in the first two Godfather films (Francis Ford Coppola, 1972, 1974), the delicious explorations of obsessive behavior in any number of Alfred Hitchcock movies, the epic treatment of Russian history in Andrei Rublev (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1966), and the tribulations of growing up in the Apu trilogy (Satyajit Ray, 1955, 1956, 1959). And there are lots of films by Howard Hawks, Preston Sturges, Luis Buñuel, François Truffaut, Robert Bresson, and Jean-Luc Godard that I would rewatch before I decide to watch Kane again. There are times when I think Welles's debut film has been overrated because he had a great start, battled a formidable foe in William Randolph Hearst, and inadvertently revealed how conventional Hollywood filmmaking was -- for which Hollywood never forgave him. It's common to say that Citizen Kane was prophetic, because the downfall of Charles Foster Kane anticipated the downfall of Orson Welles. That's oversimple, but like many oversimplifications it contains a germ of truth.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

See pinned post for the full bracket!

#best best original screenplay tournament#oscars#academy awards#best original screenplay#citizen kane#orson welles#herman j. mankiewicz#promising young woman#emerald fennell#bracket tournament#brackets#polls#poll

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz (November 7, 1897 – March 5, 1953)

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was reading all about the "auteur theory" debate over Citizen Kane, the question of whether or not its greatness is more "owed" to Orson Welles as director or Herman J. Mankiewicz as screenwriter. And I have to say the terrain of that debate is weird to me, because... the thing that makes Citizen Kane great for me isn't the script at all?? It's the visuals and the camera techniques that stand out. I don't remember any lines of spoken dialogue, but there are so many shots that the film instantly brings to mind for me because they're so eye-catching and carefully constructed. If anyone made the film great other than Welles, it's probably Gregg Toland as cinematographer.

#tbf i think when people refer to the script making the movie here they're thinking of the multiple framing devices technique#but honestly i've never found that to be used in a compelling way in film#it's just a way of introducing different periods of a person's life more or less biopic style#and i always want each person's perspective to be more subjective and rashomon style#film blogging

6 notes

·

View notes