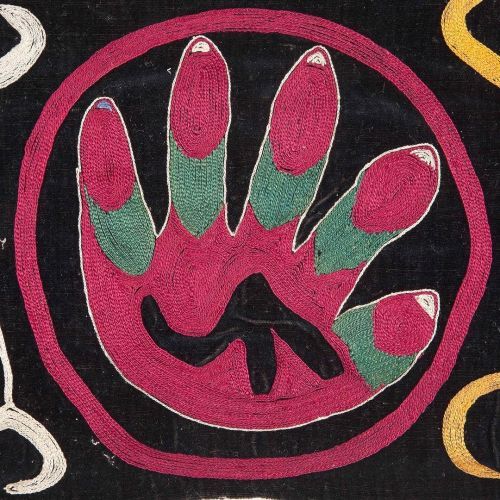

#kyrgyz nomad

Text

Otoyomegatari

#turkic#turkish#traditional#türk#nomad#artwork#art#anime and manga#manga#otoyomegatari#turkmen#turkic culture#kazakh#kyrgyz#azerbaijani#chuvash#gagauz#uzbek#bashkir#girl

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exploring the Kirghiz People: Culture, Language, and History of Kyrgyz Nomads

Uncovering the fascinating world of the Kyrgyz people

The Kyrgyz people are a fascinating Turkic people from Central Asia with a rich cultural heritage and unique way of life that captivate and inspire people around the world. In this article we cover information about their traditions, history, and experiences, providing valuable insight into this amazing community. Whether you are an avid…

View On WordPress

#Central Asia#Kirghiz culture#Kirghiz history#Kyrgyz diaspora#Kyrgyzstan#Nomadic lifestyle#Professional Interpreters#Remote Interpreting#spiritual beliefs#traditional crafts#Turkic languages#yurt living

1 note

·

View note

Note

i noticed that your banner is art of a (kazakh or kyrgyz?) falconer with a golden eagle. do you have a interest in falconry or have you ever practiced it?

Yes! I love cultures from various countries around the world, but among them, I have a special appreciation for Mongolian and Central Asian cultures. The traditional falconry culture of the Kazakh people, using majestic Golden Eagles, has left a profound impact on me. I'm truly fascinated by them.

Although I haven't had the opportunity yet, it's my dream to one day visit and experience the nomadic life of Mongolia and learn from the Kazakh falconers.

By the way, the ethnic groups featured in my creations are fictional and are a blend of various real-world cultures, incorporating elements that don't actually exist. So, please keep that in mind.

157 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I read an interesting article and I wondered if you'd feature some of the designers and dress of the World Nomad Fashion Festival?

The article

Oo--I've posted photos before from the World Nomad Games, but I didn't know they had a fashion festival!!

^Members of the Tyvan Folk Dance Ensemble of Adygea perform in clothing by designer Kima Dongak

"The World Nomad Fashion Festival is the first and only project in Central Asia and some European countries that glorifies the civilisation of nomads," the event's founder, Nazira Begim, said.

More 2022 photos

See more photos from the 2021 event below the cut!

^ designer Kima Dongak, 2021

^ designer Kima Dongak, 2021

^ designer Kima Dongak, 2021

^2021

^A model displays an outfit from the collection by Kyrgyz designer Cholponay Almaz Kyzy

^ designer Elmira Davletova, 2021

^ Kyrgyz designers Nazira Aidarova and Zukhra Kemelbekova, 2021

^ Kyrgyz designer Cholponay Almaz Kyzy

^ Kyrgyz designer Cholponay Almaz Kyzy

#kyrgyzstan#kyrgyz fashion#couture#haute couture#dance costume#costumes#costuming#headdress#men's fashion#central asia#central asian fashion#tyvan#tuvan#hats#russia#russian fashion

707 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Miss Supranational Kyrgyzstan 2022 National Costume

Kyrgyz national dress has remained virtually unchanged for seven hundred years. Kyrgyz clothing is the main part of the material and spiritual culture of the people. All outfits are closely connected with the history of the people - they clearly reflected the social status, marital status and age of the person. National clothes are extraordinarily beautiful. It is traditional clothing that is an important part of the Kyrgyz culture. From the historically established way of life associated with nomadic pastoralism, our clothes have the peculiar features of a nomadic people with a strong spirit.

And each pattern and ornament has its sacred meaning...

One of the most interesting, original and beautiful Kyrgyz headdresses is the “Shokulu” headdress of the bride. Aichurok was considered an integral part of the bride's dowry.

The most skilled craftsmen took part in the manufacture of Aichurok, in particular, a cutter, embroiderers - craftswomen in the manufacture of silk belts and scarves. Patterns on scarves and ribbons were embroidered with iris, that is, with thick twisted multi-colored threads. The center and edges of the scarves were trimmed with braided embroidery and sewing with nets. Gold, silver and bronze pendants and plaques for Aichurok were made by jewelers who used casting, chasing, stamping, filigree. Usually the master worked on Aichurok for a whole year.

Caption via Instagram

#miss supranational 2022#miss supranational Kyrgyzstan#she looks so beautiful#like a character from a fairytale#national costume contest

810 notes

·

View notes

Text

Please reblog for a bigger sample size!

If you have any fun fact about Kyrgyzstan, please tell us and I'll reblog it!

Be respectful in your comments. You can criticize a government without offending its people.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

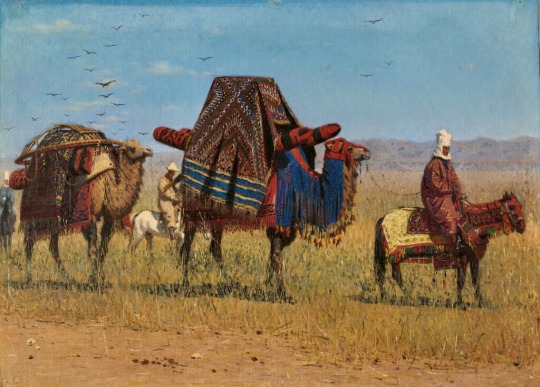

Vasily Vereshchagin (1842-1904)

KYRGYZ NOMADS

1869-1870

Material - canvas

Technique - oil

Tretyakov

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Yurts, Powder, and Global Perspectives: A Jalpak Tash Journey through Kyrgyzstan's Snow-Covered Peaks"

By Sam Thackeray

My second trip to Kyrgyzstan began with an entirely new set of emotions from the previous. My excitement about the unknowns was replaced by excitement for the knowns. The chance to see friends again, both local Kyrgyz and fellow guides from other parts of the world. To be back at Jalpak Tash and living full time out of traditional yurts. And to ride some of my favorite lines, and the possibility of riding some which had eluded us last year. Mixed in was also apprehension. Not from the uncertainty, like before, but from the preconceived notions of what this season might, or might not hold for us.

Somehow, after only doing this once prior, it all seemed so familiar. The long journey to the other side of the world felt like returning to an old haunt. There was a certain type of freedom in knowing what to expect, but also knowing what I wanted from the trip. Such as a stop at the elaborate and seemingly out of place World Nomad Games Arena. Or knowing what to expect for food at the traditional roadside stop during the journey from Bishkek, the capital city, to Karakol, the Wild West town that serves as the jumping off point for all of our trips.

I find it an interesting experience to travel to a country which has served as a “mixing pot” for thousands of years. Over the millennia Kyrgyzstan has been ruled by Persians, Mongols, Chinese, and Russians. These various influences are readily apparent in locals’ appearance, the architecture and infrastructure, vehicles, food, and religious practices. I find myself wondering what the United States might look like after a few more centuries of mixing.

A long and somewhat disorienting day of travel finds us at the guest house in Karakol, run by one of the two local families we partner with to make these trips happen. Without their support and knowledge these trips would be astronomically more challenging. We eagerly repack our bags for the journey into the mountains and succumb to exhaustion.

Day 2 in country finds us loading several weeks’ worth of gear into the infamous UAZ, the soviet era 4-wheel drive van, part jeep, part Vanagon. Excitement builds as the 40 Tribes zone comes into view and we approach the tiny village at the base the mountains to reunite with Nurbek, our camp chef, and Kas, our hut keeper and tail guide. Big hugs are shared and our bags are quickly whisked away on horse-back for the 4-mile approach to our yurt Shangri La.

The next few days are spent putting the final touches on camp, breaking in the skin tracks that act as our major arteries to the peaks, digging pits to get a feel for the snow, and of course skiing and snowboarding. Because, after all, that is what we are here to do!

Our first group arrives with good weather, sunny days, and a strong thirst for powder! We are happy to share that, while still a shallow snowpack, we have more snow than last season. Which makes for some beautiful turns and manageable avalanche conditions, allowing us to head almost immediately into the alpine. As always, we are dealing with our self-described avalanche problem, facetlanches. Cold and relatively dry weather develops an unconsolidated snowpack, which makes Kyrgyzstan a classic ski destination, but also comes with its own challenges. The faceted snow does not adhere well to steep terrain and can often be triggered by a skier or rider, but luckily these avalanches tend to be small, predictable, and incredibly slow moving. Which allows us to confidently navigate the large, alpine terrain.

Full days of powder skiing are followed by sunny apres on the yurt platforms, a feast cooked up by Nurbek for dinner, and a game or two of Yahtzee, which generally involves a couple shots of Russian Vodka. By about 8 O’Clock, everyone is ready for bed and we sink into our comfy floor beds for a long night of yurt dreams.

Living in a yurt for a week, or three, is an intimate setting. Everyone becomes familiar with each other’s habits and quirks. And it also provides for a unique opportunity to share ideas with people from around the globe. No one ends up in a yurt, in the middle of nowhere, in Kyrgyzstan, to go skiing, by accident. Everyone has unique stories, backgrounds, and tales from previous world sojourns. Life stories that all lead us to this one place in time, together. This is one of my favorite aspects of these trips. This time around I am particularly interested in Kas, the local ski guide’s take on Russia, Ukraine, and Russian’s fleeing conscription to Kyrgyzstan. It’s a complicated affair, but he doesn’t really understand the refugee’s side. In short, there are over 1 Million Russians who have fled to Kyrgyzstan to avoid fighting in the war with Ukraine. I don’t know how many have fled to other countries globally. His view is if the million in Kyrgyzstan united and marched against the Kremlin, that would be enough to oust Putin and end the conflict. An interesting point for sure, and it leaves me wondering what I would do if I were in their position? Kas says “You can have a rich country and a powerful government, or you can have freedom”. The Kyrgyz are choosing freedom.

We begin to settle into a routine. Coffee at 7, breakfast at 8, off and touring by 9:30, no alpine starts at Jalpak Tash. The days begin to bleed together in a whirlwind of powder, Yahtzee, and Vodka. Several storms move through the region changing the snowpack and avalanche conditions and, on some days, obscuring the peaks. We are able to ride in the alpine most days, but other days we take shelter in the trees and enjoy a different side of the Tian Shan. Each week is capped with a massive bonfire overlooking the Issyk Kul Valley and the distant Kungoy Ala-Too Mountains, forming the border with Kazakhstan.

Each week brings something new. A new group of guests, new weather, new opportunities to ride different lines. The yurts are beautifully situated at tree line with access to multiple peaks and ridgelines, allowing one to always feel the power of these mountains. After several hours of skinning and boot packing one can reach the summit of, what by many standards are large mountains, only to gaze to the East and see peaks looming thousands of feet above. It is quite surreal and an indescribable beauty. And then we ski 2,000 feet of powder back down to the yurts. A euphoric experience all on its own.

Over the three weeks I was there I shared yurt time, meals, and turns with fellow Americans, Canadians, Kyrgyz, Brits, Scotts, French, Australians, Kiwis, and Mexicans; continuing to mix the pot of cultures and world views. During our tenure the mountains and weather allowed us to summit the peaks many times and we were able to ski some of the classic and crown lines of the zone. Other days the mountains left us wanting more and dreaming of the lines we weren’t able to ski.

And so, we wait for another year.

-Sam Thackeray

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Russian Revolution and the Alash Orda

It’s 1917 and Central Asia is adjusting to a Tsarless reality. To briefly recap, because a lot has already happened and it’s about to get even more complicated:

Russian settlers created the Tashkent Soviet in the city, Tashkent. It is purely Russian managed and was created in response to indigenous organizing.

Various indigenous peoples such as the Jadids, the Ulama, and even the Alash Orda spent all year organizing different organs of government, ending 1917 with the Kokand Autonomy. This is an independent state created in Kokand, a city that neighbors Tashkent, in response to the Tashkent Soviet.

The Bukharan Emir kicked out his Jadids and relied on conservative elements in his society to strengthen his hold on power before Russia returns.

The Khiva Khanate is dependent on a warlord that is planning a coup.

Up to this point, we’ve focused on an Uzbek/Tajik Jadid perspective. Today we’ll be switching focus to the Kazakh and Kyrgyz intellectuals in the Steppe and the creation of the Alash Orda government and the Autonomous Alash state.

Alash Origins

As we discussed in our interview with Dr. Adeeb Khalid, the Muslim world was going through severe soul searching in the 1900s as they tried to understand the rise of European empires and the crumbling foundation of, not just the Ottomans, but Islamic nations in general. This was true in the Kazakh Steppe as well, although for the Kazakh intellectuals, it wasn’t just a question of how does Islam survive, but how do we define Kazakhnessand how do we ensure it survives?

The Kazakh identity crisis was sparked by the land crisis. We’ve talked about this in some of our other episodes, but starting in 1890, Russian settlers streamed into the Kazakh lands, taking important arable land that the nomadic Kazakhs relied on to survive. The Russians performed several exhibitions and surveys in the region between 1890 and 1912 and the Kazakh land grew ever smaller and smaller. Of course, this came to a head in 1916 and by 1917 the Tsar was gone, Russia was in disarray, and the Kazakh peoples had an opportunity to create their own government and address land rights.

Yet, while there was a real threat from Russian incursion, the Kazakhs also took advantage of opportunities the Russian presence offered. Many Kazakhs learned Russian and went to school in Russian run schools as well as local Kazakh schools (as opposed to the madrasa education mandated in places such as Tashkent and Bukhara), they had a long history of trading and even working with Russians, and the Kazakhs were also familiar with the Tatars and even the indigenous people of the Siberian oblast that the Russians relied on to support their colonial administration. And in an odd way the land crisis brought the Kazakhs closer to their Kyrgyz and Bashkir neighbors because they were experiencing the same problem.

This connection with Siberia seems to have provided the Kazakh intellectuals the support they needed to survive Russian persecution and take their ideas and grow it into a full-fledged movement. In fact, there is a great article by Tomohiko Uyama which details how the Russia attempts to banish important Kazakh activities such as Akhmet Baitursynov and Mirjaqip Dulatov to the outskirts of the Steppe (and sometimes in Siberia itself) allowed them to make widespread connection with other activities as well as each other and only fanned the flames of their work.

Akhmet Baitursynov described this time in Kazakh society as being caught between “two fires”: the influence of Muslim culture and the influence of Russian and Western culture. Out of this tension came the Alash, modernizing intellectuals. But even the Kazakh intellectuals couldn’t decide what was the best way to save Kazakhness, so they split into two big-picture groups: the Western-centric modernizers who were the editors for the newspaper Qazaq and the Islamic-centric modernizers who were the editors for the newspaper Aiqap. Some of the most important editors of the Qazaq newspaper was Akhmet Baitursynov, who was editor-in-chief, Alikhan Bokeikhanov, and Myrzhaqyp Dulatov, and they would go forth to become key members of the future Alash state. Some of the most important editors of the Aiqap newspaper were Mukhamedzhan Seralin, Bakhytzhan Qaratev, and Zhikhansha Seidalin.

What was the Alash platform? The two key pillars of their platform were land rights and preserving Kazakh identity.

Akhmet Baitursynov, Alikhan Bokeikhanov, and Myrzhaqyp Dulatov

[Image Description: An image of three Asian men sitting together. The man on the left has short black hair and a droppy mustache. He is wearing glasses and a white shirt, black tie, and black suit. The man in the middle has shaved black hair and a heavy mustache. He is also wearing a white shirt, black tie, and black suit. The man on the right has black hair and thin mustache. he is wearing a white shirt, a black bowtie, and a grey suit.]

Land Rights

We’ll start with land rights, because that is why really differentiates the Steppe from the rest of Central Asia. As we mentioned, the Russians were taking Kazakh land, and making land ownership dependent on one’s sedentary behavior. The Russians also published numerous pieces of propaganda belittling nomadic life. So, the Kazakhs had to determine whether to maintain their nomadic lifestyle or adopt a sedentary lifestyle.

Bokeikhanov, an editor of Qazaq newspaper, argued that the Russians wanted the Kazakh to settle down so they could give even more land (and most certainly the best land) to the Russians while giving the useless land to the Kazakhs and then blaming them for failing. Baitursynov picked up that argument and pointed out that the Kazakhs could not succeed unless they first learned how to farm, but the Russians weren’t interested in that aspect of sedentary life at all. They just pushed the Kazakhs to settle down and worry about the rest later. This could have come out of Russia’s (and the Tatar’s) lack of knowledge of the Kazakh situation but could have also been purposeful ignorance.

Bokeikhanov and Baitursynov argued for a gradual transition to sedentarization due the Steppe’s climatic conditions and lack of agricultural knowledge otherwise they would risk starvation (which Stalin proved in the 1930s). In a series of article, they argued that:

“If we ask what kind of economy is more suitable for Kazakhs-the nomadic or the sedentary-the question is incorrectly posed. A more correct question would be: what kind of economy can be practiced under the climatic conditions of the Kazakh steppe? The latter vary from area to area and mostly are not suitable for agricultural work. Only in some northern provinces do the climatic conditions make it possible to sow and reap. The Kazakhs continue wandering not because they do not want to settle down and farm or prefer nomadism as an easy form of economy. If the climatic conditions had allowed them to do so, they would have settled a long time ago.” - Gulnar Kendirbai, '"We are Children of Alash...", pg. 9

Displaying a better understanding of the science behind climate and agriculture than the Russians or the Soviets that would follow, the editors argued that the climate was the number one factor in nomadism and the Kazakhs could not become sedentary until they learned how to adjust to the demands of the land. Another article argued that sedentarism would lead to failed farming which would lead to wage work which led to great abuses and a higher chance of being converted to Christianity, so the Kazakhs must also learn handicrafts in addition to science. They described the Russian’s disinterested in their arguments as

“One may compare it with the dressing some Kazakh in European fashion and sending him to London, where he would either die or, in the absence of any knowledge and relevant experience, work like a slave. If the government is ashamed of our nomadic way of life, it should give us good lands instead of bad as well as teach us science. Only after that can the government ask Kazakhs to live in cities. If the government is not ashamed of not carrying out all the above-mentioned measures, then the Kazakhs also need not be ashamed of their nomadic way of life. The Kazakhs are wandering not for fun, but in order to graze their animals.” - Gulnar Kendirbai, '"We are Children of Alash...", pg. 10

It should be noted that the Alash did not equate nomadism with Kazakh identity. Instead, they argued that the Kazakhs (and I would argue extend that to the Kyrgyz and Bashkirs) were nomadic for a sensible and scientific reason and if the Russians were truly interested in helping the Kazakhs successfully transition to sedentarism, then they needed to provide the tools otherwise they were setting the Kazakhs up for failure.

Mukhamedzhan Seralin, an editor of the Aiqap newspaper, believed that the sooner the Kazakhs settled down the sooner they could gain a European level education and become competitive in the modern world while increasing the role of Islam in Kazakh society. He argued that:

“We are convinced that the building of settlements and cities, accompanied by a transition to agriculture based on the acceptance of lands by Kazakhs according to the norms of Russian muzhiks, will be more useful than the oppose solution. The consolidation of the Kazakh people on a unified territory will help preserve them as a nation. Otherwise, the nomadic auyls will be scattered and before long lose their fertile land. Then it will be too late for a transition to the sedentary way of life, because by this time all arable lands will have been distributed and occupied.” - Gulnar Kendirbai, '"We are Children of Alash...", pg. 10

The editors of Aiqap argued with the others on the need for greater education, various options for work, etc., but they believed that the Kazakhs could never have these things untilthey became sedentary whereas the editors of Qazap believed that the Kazakhs could not become sedentary until they had those things.

Kazakh identity

This leads to the second pillar in the Alash platform: preserving Kazakh identity.

For the Kazak intellectuals of all stripes, the second most important element of Kazakh society was education and literature. They were worried about the poor education opportunities that centered Kazakhness instead of Russianness, available to Kazakh children. Even after primary school, the Kazakh educational options were limited: either they try to get accepted into a madrassa or go to Russia for further education. The Kazakh intellectuals learned of the new teaching methods the Jadids championed via their southern neighbors as well as the Tatars in the area and used literature to encourage the Kazakh people to focus on schooling.

Akhmet Baitursynov was focused on reforming primary schools and the lack of teaching materials, especially on the Kazakh language. The Qazap newspaper was the only newspaper who wrote in pure Kazakh. Baitursynov answered their detractors as followed:

“Finally, we would like to tell our brothers preferring the literary language: we are very sorry if you do not like the simple Kazakh language of our newspaper. Newspapers are published for the people and must be close to their readers.” - Gulnar Kendirbai, '"We are Children of Alash...", pg. 19

The Kazakh intellectuals resisted the Tatar clergy’s attempts to subsume Kazakh language to the Tatar language, eventually arriving at a compromise. This pressure around language inspired Akhmet Baitursynov to reform the Kazakh language, creating spelling primers, and improving the Kazakh alphabet multiple times. This book was soon used in primary schools. He also published a textbook on the Kazakh language which studied the phonetics, morphology, and syntax of the Kazak language as well as a practical guide to the Kazakh language and a manual of Kazakh literature and literary criticism.

Meanwhile Bokeikhanov focused on creating a unified Kazakh history, believing that “History is a guide to life, pointing out the right way.” Together Bokeikhanov and Baitursynov focused on collecting Kazakh folklore, the history of their cultures and traditions, and shared world history with other Kazakhs through their newspapers. They encouraged Kazakh writers to write down their poems and stories, fearful that they would be lost if Kazakhs stuck purely to an oral tradition.

For intellectuals like Bokeikhanov and Baitursynov, Kazakhness was connected to a cultural identity as opposed to a religious identity. Bokeikhanov supported the idea of separation between religion and state and resisted the Aiqap’s call for introduction to Sharia law. Bokeikhanov believed that they should codify and record Kazakh laws, customs, and regulations to counter corruption and bribery, instead of relying on Sharia law. The Kazakh people had a different relationship to Islam than the other peoples of Central Asia (which may have been why the Russian missionaries were initially confident the Kazakhs would be easiest to convert). While the editors of Aiqap believed that sedentary life would create closer ties to Islam, the editors of the Qazap newspaper believed that Islam was a part of Kazakh society but didn’t equal Kazakh society.

1905 Russian Revolution

We’ve talked quite a bit about what the Alash stood for, but how did this translate into political action? The Kazakhs, like many other Central Asians, were initially excited about the 1905 Revolution, which created a State Duma that “welcomed” Central Asians as members for about two Dumas. When the Kazakhs could participate, they sent Alikhan Bokeikhanov and Mukhamedjan Tynyshpaev.

After the Second Duma, the Kazakhs were no longer permitted to send their own deputies, so they either had to rely on the Tatar deputies of the Muslim Faction of the Russian Duma or find support elsewhere. The Kazakh intellectuals believed that the Tatars had no real knowledge of Kazakh needs and distrusted them. So, they turned to the Russian Constitutional-Democratic Party i.e., the Kadets.

The Kadets sold themselves as an umbrella party that advocated for civil rights, cultural self-determination, and local legislation that would allow for the use of native languages at schools, local courts, administrations, and institutions. Even though the Kadets and the Alash didn’t agree on land rights, they still became allies. The tension between the two parties would not disappear, especially following the 1916 Revolt (which the Alash, like the Jadids, tried to prevent), but they also acknowledged that the Kadets were the only game in town.

1917 Russian Revolution

The 1917 Revolution changed all of that by allowing the indigenous peoples and settlers to create their own forms of government. In April 1917, they would form their own All-Kazakh Congress in Orenburg where they passed a resolution calling for the return of Steppe land to Kazakh peoples, control over local schools, and the expulsion of all new settlers in Kazakh-Kyrgyz territories.

The Alash used 1917 to win local support, focusing on winning the support of the most influential leaders of the local communities and trusting the elders to use tribal affiliations to mobilize the people under the Alash banner. The Kazakh intellectuals dug deep into Kazakh history to unify the people under Alash, the father of all Kazakhs, creating a unified history from creation to modernity. This can be thought of as similar to the Jadids attempts to trace Uzbekness back to Timur.

They also worked with the Provisional Government in Russia, and with the various councils and meetings held by their Jadid counterparts in Turkestan, but ran into great friction because their Tatar, Uzbek, Tajik, etc. counterparts didn’t truly appreciate how important the land issue was for the Kazakhs. They were also wary of the Ulama’s version of a council, wanting to maintain the traditionally limited role of Islam in Kazakh society.

Because of the differences in priorities and the role of Islam, the Alash would go their own way while continuing to support the efforts of other indigenous peoples. They would continue to serve on the various councils and even took part in the creation of the Kokand Autonomy, but knew they needed their own Congresses and their own autonomous state to protect their people and achieve meaningful land reform.

The Kokand Autonomy created three seats for Alash members, believing that two southern Kazakh oblasts would be part of the Kokand Autonomy whereas the Alash wanted a unified Kazakh state. Bokeikhanov explained the Alash’s position as follows:

“Turkestan should first become an autonomy on its own. Some of our Kazakhs argue it would be correct to join the Turkestanis. We have the same religion as the Turkestanis, and we are related to them. Establishing an autonomy means establishing a country. It is not easy to lead a country. If our own Kazakhs leading the country are unfortunate, if we make the argument that Kazakhs are not enlightened, then we can argue that the ignorance and lack of skill among the people of Turkestan is 10 times higher than among Kazakhs. If the Kazakhs join the Turkestani autonomy, it would be like letting a camel and a donkey pull the autonomy wagon. Where are we headed after mounting this wagon?” - Ozgecan Kesici, 'The Alash Movement and the question of Kazakh ethnicity', 1145

The Alash similarly considered joining the Siberian Autonomy movement but broke away once more over the issue of Kazakh autonomy. As Bokeikhanov explained:

“In practice, the autonomy of our Kazakh nation will not be an autonomy of kinship, rather, it will be an autonomy inseparable from its land.” - Ozgecan Kesici, 'The Alash Movement and the question of Kazakh ethnicity', 1146

Failing to find neighbors who would respect their autonomy and facing extreme violence because of the Russian Civil war that was working itself way through Siberia, the Alash would proclaim the creation of the Alash Autonomy during the Second All-Kazakh Congress in December 1917. This would be the first time a Kazakh state existed since the Russian invasion in 1848. This autonomous state would be ruled by the Alash Orda, a government made up of many of the modernizing intellectuals who worked at the Qazap and Aiqap newspapers. Alikhan Bokeikhanov was elected its president. Whatever relief they may have felt at creating a state government must have been quashed by the understanding that civil war was at the Steppe’s door and sooner or rather they would have to choose a side and risk their long fight for autonomy.

References

'Challenging Colonial Power: Kazakh Cadres and Native Strategies' by Gulnar Kendirbai, Inner Asia 2008, Vol 10 No 1

'"We are Children of Alash..." The Kazakh Intelligentsia at the beginning of the 20th century in search of national indeitty and prospects of the cultural survival of the Kazakh people' by Gulnar Kendirbai, Central Asian Survey, 1999, Vol 18 No 1

'The Alash Movement and the question of Kazakh ethnicity' by Ozgecan Kesici, Nationalities Papers, 2017, Vol 45 No 6

'Repression of the Kazakh Intellectuals as a sign of weakness of Russian Imperial Rule'by Tomohiko Uyama Cahiers du Monde russe 2015 Vol 56, No 4

Making Uzbekistan: Nation, Empire, and Revolution in the Early USSR by Adeeb Khalid

Russia and Central Asia: Coexistence, Conquest, Coexistence by Shoshana Keller Published by University of Toronto Press, 2019

#history blog#season 2: central asia#central asian history#central asia#kazakhstan#qazaqstan#qazaq history#kazakh history#alikhan bukeikhanov#Akhmet Baitursynov#Spotify

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kyrgyz

#turkic#traditional#nomad#culture#turk#kyrgyz#kyrgyzstan#central asia#asian#traditional clothing#traditional dress#turkic culture

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

1) Buryatia + nyo!Mongolia

2) Kyrgyzstan + Mongolia and (Yenisei) Kyrgyz

After its establishment, Mongol Empire quickly subjugated Turkic confederations and groups in the territory of Mongolia and around the Baikal such as Kerait, Naiman, Merkit, Tatar, and Yenisei Kyrgyz (though Merkit was probably Mongolic). All these Turkics were Mongolia’s first harem. In the end, only the Kyrgyz would survive as distinct people into the current time as most of them became modern Kyrgyz people in Kyrgyzstan. The others were quickly absorbed into Mongolians or Kazakh.

It’s unknown whether Kyrgyzstan is the former Yenisei Kyrgyz or if he is a successor who carries the latter’s memories, but Mongolia feels familiar with Kyrgyzstan beyond what he would feel about a country who happens to share a similar nomadic culture. As it stands, today’s Kyrgyzstan looks different from the mostly West Eurasian Yenisei Kyrgyz, but Mongolia almost swears they’re the same person. Mongolia could also differentiate easily between Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan even when many others aren’t able to (“How are you not able to distinguish them? They’re massively different!” Says Mongolia)

(I gave Yenisei Kyrgyz Göktürk era clothing as I haven’t found their specific costume, lol)

3) Golden Horde + baby Golden Horde carried by Mongolia

When Golden Horde was newly born, he was close to Mongolia who would often carry him everywhere (or let his horse do the job). Think of a toddler who stares unblinkingly at you from underneath all the fur wrapped around his tiny body as if trying to drill a hole into the area between your eyes. Meanwhile, Mongolia would smile proudly at him.

#hetalia#aph mongolia#oc golden horde#oc kyrgyzstan#oc buryatia#hws mongolia#hws golden horde#hws kyrgyzstan#hws buryatia#my art#my headcanon

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

For more than two decades, Central Asian labor migrants have traveled to Russia for work. Now, with Russian President Vladimir Putin’s announcement of a compulsory military draft, hundreds of thousands of Russians are heading in the opposite direction.

Since Putin’s announcement of Russia’s first military mobilization since World War II on Sept. 21, hundreds of thousands of Russian men have left the country to avoid being drafted to fight in Ukraine. The former Soviet republics of Central Asia quickly emerged as a primary destination for Russian draft dodgers looking for the nearest safe, affordable, and legal exit out of Russia. With airfares skyrocketing, Russian men have been rushing to Russia’s southern border, since they can enter Kazakhstan visa-free with only their internal passports—a mandatory ID issued to all citizens—in hand, sometimes moving farther south to Kyrgyzstan, which has the same policy. That’s a lifeline for the estimated 70 percent of Russian citizens who are not in possession of a passport for international travel.

According to Kazakh officials, more than 100,000 Russian citizens, and possibly as many as 200,000, have crossed over into Kazakhstan since the start of mobilization, many of whom have continued farther south into neighboring Kyrgyzstan. As citizens of a member state in the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), Russians enjoy the right to work and reside in both countries, like other EEU members, on the condition that they register their arrival with local migration authorities. Once released, registration statistics should provide a better picture of the scale of this exodus, but it is already clear that Central Asia is confronted with an unanticipated Russia migration crisis.

Long perceived as a buffer zone, post-Soviet Central Asia received significant amounts of military equipment, aid, and training from the international community in order to contain the threat of a mass exodus of refugees from Afghanistan. None of this assistance, however, could have prepared the region for this unprecedented influx of people from its former colonial and imperial center.

The first wave of Russians moving abroad after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February referred to themselves as relokanty—a term borrowed from the tech industry in reference to employees relocated abroad by their companies. Aside from political dissidents, most of those who left in the first six months of the war had the social capital and financial resources for a relatively smooth and orderly relocation of their families and businesses abroad to places such as Turkey, Georgia, Armenia, and—to a lesser degree—Central Asia.

Kyrgyzstan welcomed almost 30,000 Russian citizens in the six months leading up to mobilization. Some gained residency in Kyrgyzstan with the sole purpose of opening a bank account to circumvent Western sanctions, while others set up shop in the country on a more permanent basis. Seeing the large number of tech workers among Russian exiles, the Kyrgyz government was quick to launch a special Digital Nomad program that allows Russian programmers and IT specialists to stay in the country without registering or having to obtain a work permit.

The face of Russian exile is changing. Unlike their relatively well-off peers in the tech industry, many of the recently arrived draft dodgers are in more precarious financial situations. Hailing from smaller cities in Siberia, the Urals, and the Russian Far East, some of these young men crossed into Kazakhstan on foot with little more than a suitcase and a lack of transferrable skills or experience..

Central Asian states have kept their borders open to Russian draft dodgers since the start of mobilization, with Kazakhstan’s interior minister assuring Russians fleeing conscription that they would not be extradited to Russia. In Kazakh cities close to the Russian border, volunteers are distributing food and drink to recently arrived Russians as movie theaters, mosques, and gymnasiums have been turned into makeshift sleeping quarters. Finding temporary accommodation has become a struggle across Central Asia, with hotels, hostels, and guesthouses booked out for weeks ahead.

Many of Central Asia’s cities are already on the brink of a housing crisis with unscrupulous landlords doubling—and sometimes tripling—rental prices overnight. In Almaty and Bishkek, public discontent is rising, with reports of local tenants being forced from their apartments to make way for desperate Russians willing to pay more than double the average local monthly salary in rent.

The situation is particularly tense in Kyrgyzstan—a country still recovering from the violence and destruction caused by clashes with Tajikistan along the countries’ border that ended just a day before Putin’s mobilization decree. Before the latest surge in migrants from Russia, Kyrgyzstan’s major cities were already struggling to provide temporary accommodation to the thousands of residents displaced by the conflict. To make matters worse, many of the Kyrgyz migrants returning to the country, after spending several years in Russia, are relocating to Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan’s largest city, putting additional strain on an already saturated housing market.

Russian exiles are having to rely on the hospitality of a Central Asian population that has greatly suffered from stigmatization, racism, and discrimination under the pejorative label of “migrants” within Russian society. In a region where hospitality toward visitors is perceived as part of the national character, Russian émigrés have encountered a welcome reception. At the same time, there is palpable sense of anger and schadenfreude among some Central Asians at having to assist their former colonial oppressors. In Bishkek and Tashkent, the Uzbek capital, local activists and mutual aid groups have therefore placed an emphasis on organizing cultural sensitivity trainings and public lectures on the history of Russian imperialism and Soviet hegemony in the region. These initiatives aim to push Russians to think critically about their country’s past and help undo some of the prejudices toward Central Asia that have been so prevalent in Russian society.

Given the immense suffering of the Ukrainian people at the hands of the Russian military, there is understandably little sympathy globally for Russian draft dodgers fleeing abroad. There has been a reluctance to refer to these exiled Russians as refugees, although the 1951 U.N. Refugee Convention is supposed to also cover draft evaders who refuse to commit war crimes and acts of aggression. Regardless of whether they are officially recognized as refugees by certain states, these temporary exiles will soon find themselves in an increasingly precarious situation as repressions in Russia intensify and the mobilization drive continues. While those lucky enough to have professional or family connections abroad will eventually be able to relocate to other countries, many of the youngest and most vulnerable Russian draft dodgers may remain trapped in Central Asia.

This humanitarian crisis in the making will require assistance from the international community, as Central Asian states lack the resources and infrastructure to host indefinitely such a large refugee population. Major international organizations such as the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and the International Organization for Migration will need to assist local governments in their emergency responses to the Russian migration crisis. While informal networks and mutual aid groups have played an incredibly important role in supporting Russian new arrivals, they are currently at capacity and would benefit from external assistance in terms of providing basic essentials and temporary housing.

With most of the European Union’s eastern border closed off to Russian travelers, EU member states could work toward resettling Russian draft evaders currently in Central Asia. Germany has already expressed a willingness to offer international protection to those fleeing Putin’s forced conscription—an important step in the right direction. With low-to-middle-income countries already hosting most of the world’s refugees, the former Soviet republics of Central Asia cannot be left alone to carry the burden of supporting an exiled population.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ruh Ordo Açık Hava Müzesi, Issık Gölü kıyısında Kırgız kültürünü anlatmak için kurulmuş bir kültür merkezi. . Girişin ücretli olduğu merkezde farklı dinleri anlatan yapılar bulunuyor. Ayrıca tabii ki tarihteki en önemli Türk Lider olan Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’ün bir heykeli sergileniyor. . Kırgızların Cengiz Aytmatov sevgisi sorgulanamaz, yazara özel bir sergi salonu ile bahçede heykeli sergilenenler arasında. . Merkez, Bişkek’e 260 km mesafede Çolpan Ata şehrinde bulunuyor. Çolpan Ata’ya gelmişken Petroglif Açık Hava Müzesi de görülecek yerler listenizde olsun. . Çolpan Ata ayrıca ülkenin en büyük Kök Börü müsabakalarına ev sahipliği yapan stadyumun bulunduğu şehir. Uluslararası Göçebe Oyunları (Nomad Games) Kırgızistan kısmı burada gerçekleşmiş. . #çokgezenkırgızistan #kyrgyz #ruhordo #cholpanata #nomadgames (Ruh Ordo) https://www.instagram.com/p/CgcA-4hjxVT/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 8 Mind-Breaking Places to Visit in Kyrgyzstan

Take a journey across Kyrgyzstan's amazing landscapes and cultural valuables, where every turn reveals a weaving of delights that engage the spirit. Kyrgyzstan attracts with its unbelievable array of experiences, from the amazing beauty of Issyk-Kul, the second-largest highland lake in the world surrounded by snow-capped peaks, to the ancient mysteries shrouding the Silk Road capital of Osh. Explore the strange scenery of the Tian Shan mountains, where green valley's give way to rocky canyons and beautiful glacial lakes and get a taste of the Kyrgyz people's nomadic ways amid Song Kol's grasslands filled with yurts. Get ready for an experience that will exceed your expectations and leave a lasting impression on your soul.

With our premium Kazakhstan tour packages, you can set out on incredible journey through country's expansive landscapes and unique cultures. Our Kazakhstan holiday packages, which are customised to each traveller's interests and preferences, provide an effortless fusion of adventure, culture, and relaxation. Explore historic Silk Road cities of Turkestan and Shymkent, colourful bazaars and centuries-old monuments attract you with stories of ancient periods. Experience the natural beauty of the Altai Mountains or the calm shores of Lake Balkhash for those who love the great outdoor. Exciting outdoor activities await you among incredible scenery. You're looking for peaceful getaway, thrilling adventure, or cultural immersion, our Kazakhstan holiday packages guarantee an amazing experience that will amaze and inspire you.

Here are the 8 Mind-Breaking Places to Visit in Kyrgyzstan:

Lake Issyk-Kul:

The beautiful mountain lake known as Lake Issyk-Kul, or "Warm Lake," can be found away among the Tian Shan Mountain range. It is an important part of Kyrgyzstan's geography and culture, and it is second-largest alpine lake in the world. Issyk-Kul offers extensive variety of activities for relaxation, including swimming, tanning, boating, fishing, and yachting, thanks to its clean water, sandy beaches, and calm atmosphere.

Ala Archa National Park:

Ala Archa National Park is nature lover's dream come true, offering variety of environment such as alpine meadows, lush woods, icebergs, and towering hills. It is only a short drive from Bishkek, the capital city. Numerous outdoor activities are available in the park, hiking, trekking, rock climbing, picnics, and wildlife observation. Numerous trails are available for exploration, including the difficult Ak-Sai Glacier, the beautiful Ratsek Hut, and the amazing Ala-Kul Lake excursion, which offers expansive views of the neighbouring mountains.

Osh:

Osh, one of the oldest cities in Central Asia, is rich in culture and history, having been around for more than 3,000 years. Situated in the lush Ferghana Valley in the southern region of Kyrgyzstan, Osh presents an extensive variety of backgrounds, lively marketplaces, and historic sites. UNESCO-listed Sulaiman-Too Sacred Mountain, Muslim pilgrimage site and symbol of religious value, is the city's most popular attraction.

Song Kol Lake:

Situated in the high-altitude plateau of Naryn Province at 3,016 metres above sea level, Song Kol Lake is an amazing mountain lake that is well-known for its amazing natural beauty and traditional customs. Song Kol, surrounded by rolling hills, beautiful meadows, and snow-capped peaks, provides tourists with a rare chance to experience genuine nomadic Kyrgyz culture.

Karakol:

Karakol is a stunning town that is well-known for its historical sites, different cultures, and outdoor activities. It is located at the easternmost point of Issyk-Kul Lake. Karakol, which was first established in the 19th century as a Russian military outpost, has developed into a thriving cultural hub that is influenced by Kyrgyz, Russian, and Dungan traditions. Among town's architectural attractions is beautiful Dungan Mosque, which was constructed in traditional Chinese style using no nails at all.

Skazka Canyon (Fairy Tale Canyon):

Hidden away in Kyrgyzstan's Issyk-Kul area, Skazka Canyon, sometimes called Fairy Tale Canyon, is a natural wonder famous for its bright colours and unique rock formations. The canyon's high sandstone mountains, colourful formations, and layers of sedimentary rock in shades of red, orange, and yellow, carved by ages of wind and water erosion, create an invisible scene suggestive of a realm from fairy tales.

Tash Rabat Caravanserai:

Tash Rabat Caravanserai, which is hidden away in the isolated mountains of Naryn Province, is a monument to Kyrgyzstan's rich past as crossroads of civilizations along historic Silk Road. Stone caravanserai dates back to 15th century and was an important resting place for traders, merchants, and tourists making their way through dangerous mountain passes that connect China with Central Asia.

Sary-Chelek Biosphere Reserve:

The Sary-Chelek Biosphere Reserve is a pure wilderness area known for its biodiversity, graphic beauty, and conservation activities. It is situated in the unspoiled highlands of Jalal-Abad Province. Reserve, which is home to rare and endangered species like snow leopard, lynx, and golden eagle, is made up of thick woods, mountain meadows, and beautiful lakes.

Conclusion:

As your time in Kyrgyzstan comes to a conclusion, the variety of experiences this beautiful country has to offer will leave you speechless. For every traveller fortunate enough to venture into its depths, Kyrgyzstan creates lasting impact, from rough beauty of mountain ranges to warmth of its kind people. Take with you the memories of this land of infinite wonder, it's strange landscapes, its rich history of culture, and the deep bond that is formed between visitor and location as you wish it farewell. With every visit, Kyrgyzstan encourages travellers to come back and explore mysteries once more. For more details visit best travel agency in Dubai

0 notes

Text

There is a unique tradition in Kyrgyzstan where bars, also known as taverns, are believed to serve as a sort of "conditioner for gods." This concept may seem unusual to outsiders, but it holds great significance in the culture of Kyrgyzstan.

In Kyrgyzstan, it is believed that the gods live in the mountains and are closely connected to nature and the elements. These deities are thought to bring good fortune, protection, and prosperity to the people. As a way to honor and welcome these gods, the local community has developed the custom of offering drinks and food to them in the form of "conditioners."

Bars in Kyrgyzstan are known for their unique architecture and design, with furnishings and decor reflecting the traditional nomadic and yurt-dwelling culture of the Kyrgyz people. These establishments are seen as sacred places, where people gather to pay their respects to the gods and offer them refreshments.

This tradition of offering drinks to the gods in bars has been passed down for generations, and it is deeply ingrained in the Kyrgyz way of life. It is believed that by honoring the gods in this way, people will receive blessings and good luck in return.

The concept of using bars as a "conditioner for gods" also serves as a way to maintain a strong connection with nature and the mountains, which are considered sacred in Kyrgyzstan. This belief is deeply rooted in the nomadic lifestyle of the Kyrgyz people and their close relationship with the land.

Moreover, bars in Kyrgyzstan are not only seen as a place to connect with the gods, but also as a social hub for the community. They serve as a meeting place for friends and families, a source of entertainment, and a way to preserve cultural traditions.

The practice of offering drinks to the gods in bars has become so ingrained in Kyrgyz society that it is now a regulated part of their business. For example, bar owners are required to have a special shelf or table dedicated to the gods’ offerings. This not only serves as a reminder to patrons to honor the gods, but also ensures that the tradition is carried out in a respectful manner.

In conclusion, the concept of bars being "conditioner for gods" in Kyrgyzstan is a unique tradition that reflects the deep cultural and spiritual beliefs of the Kyrgyz people. It serves as a way to honor and connect with the gods, preserve traditional customs, and maintain a strong connection with nature. So, if you ever find yourself in a Kyrgyz bar, be sure to raise a glass to the gods and soak in the rich culture and traditions of this beautiful country.

0 notes