#lampropeltis elapsoides

Text

A scarlet kingsnake (Lampropeltis elapsoides) in the Georgia Piedmont, USA

by Noah K. Fields

#scarlet kingsnake#kingsnakes#snakes#reptiles#lampropeltis elapsoides#lampropeltis#colubridae#serpentes#squamata#reptilia#chordata#wildlife: georgia#wildlife: usa#wildlife: north america

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

today's mimic: scarlet kingsnake, lampropeltis elapsoides

photo by peter paplanus

the scarlet kingsnake is a non-venomous snake found in the eastern US. it mimics certain coral snakes, such as the eastern coral snake, which have very similar red, black, and yellow/white bands. coral snakes are highly venomous, so by mimicking the distinctive colouration of these more dangerous snakes, the scarlet kingsnake is less likely to be predated upon. this is a commonly cited example of batesian mimicry, where a harmless organism mimics the danger signals of another organism that it shares a predator with.

model:

photo by jonathan mays

#mimicposting#defensive mimic#animal mimic#vertebrate mimic#visual mimic#scarlet kingsnake#lampropeltis elapsoides#snakes#biology#mimicry#animal facts#educational

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

All of my Tiny Reptile designs from 2023! Identifiers for each reptile under the cut.

Jackson's Chameleon (Trioceros jacksonii)

Eyelash Viper (Bothriechis schlegelii)

Alligator Snapping Turtle (Macrochelys temminckii)

Central Bearded Dragon (Pogona vitticeps)

Eastern Snake-Necked Turtle (Chelodina longicollis)

Scarlet Kingsnake (Lampropeltis elapsoides)

Western Box Turtle (Terrapene ornata)

Yellow-Headed Day Gecko (Phelsuma klemmeri)

Costal Rosy Boa (Lichanura orcutti)

Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia mydas)

Blue Coral Snake (Calliophis bivirgatus)

Komodo Dragon (Varanus komodoensis)

449 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scarlet Kingsnake (Lampropeltis elapsoides), family Colubridae, Florida, USA

Coral snake mimic.

photograph by Florida Fish and Wildlife/Flickr

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

Coat of Gender, 2022

The idea of a Coat of Gender is originally from Orion Scribner (@frameacloud). The original Read Mores that went with their gender heraldry comics are no longer on their Tumblr, but you can find the reblogs of the comics themselves on my blog here and here. The functional idea is a “…form of heraldry, in which each person can create their own coat of arms to describe their gender identity and expression.” My friends Nova also made a CoG here, you should check it out! Consider making one yourself too!

I used to make an updated CoG every year to see the different ways my presentation and expression would change over time, but I dropped off in 2020 when the pandemic hit and after I graduated college. So it's really nice to get to pick this back up, and to hopefully start the yearly tradition again!

Click the "Read More" below for the Symbolism Key and general information. Click the links below to see the good (and the not-so-good) past versions of my Coat of Gender.

2016 & 2017 Versions - 2019 Version

The Top Banners:

The top banners read “Mx.” (my preferred honorific), “He - They” (my preferred pronouns). While I've had these banners separate in the past, I decided to interconnect them onto a single ribbon in this new version because I've found that my preference towards androgynous/masculine pronoun sets is directly intertwined with my preferred honorifics-- I generally prefer "Mx." but secondarily also accept "sir" and similar masc-oriented terms when gender neutral ones are not available.

The Bridge:

Like in previous versions of my CoG, the bridge is meant to represent that I consider myself transgender in addition to nonbinary, and have plans to partially transition in my future. The lampposts at both ends of the bridge are akin to ‘light at the end of the tunnel’ symbolism, but with the additional acknowledgement of the bright things in my past which have helped me and are helping me cross the metaphorical bridge of gender transition and acceptance. In this new version, I've changed the bridge from stone to wood for aesthetics, and because I think it feels a little cozier, reminiscent of my days playing Minecraft with friends and loved ones. I deserve a cozy and warm transition, surrounded by the people I love, and this reminds me of that.

The Shield Shape:

Like my last CoG, this shield is meant to mimic a hanging banner or pennant. I display my gender loudly and proudly, putting it high for all to see, no matter what anyone says, and this is meant to reflect that. We changed the shape from three points at the end to five points, to represent one point for each systemmate, a reference to our plurality's influence on our gender identity.

The Field (Shield Colors):

The yellow/gold represents optimism regarding personal acceptance and future societal tolerance of nontraditional gender identities, and is also meant to reflect the draconic aspects and influence of my gender identity: both as a reference to dragons quite literally hoarding gold, and as a reference to my own personal draconic identity, in which I have silver scales. The grey, white, red, and black are our system colors, each representing a systemmate: I'm grey-furred, Noel is white-scaled and red-eyed, Drago is red-scaled, Wyvern is black, and Dash is red-and-black-scaled. Another reference back to the ways plurality affects my gender identity.

The Support (Animals, Plants, Decorations):

The left support is Micrurus fulvius, commonly known as the Eastern Coral Snake or "American Cobra." The right support is Lampropeltis elapsoides, commonly known as the Scarlet Kingsnake or Scarlet Milksnake. Both are native to my home state, Florida, and I have happened to see both in my lifetime-- one in the wild and in captivity, the other just in captivity. Coral Snakes and Scarlet Kingsnakes are often mistaken for one another, and can be hard to distinguish if you don't know what differences to look for: in the same way, it can be hard for cis people and people unfamiliar with nonbinary gender identities, especially more complex and nonhuman-oriented ones, to understand the ways I'm different from a cisgender individual, or the way my own gender is different from that of my systemmate's while still also being connected to ideas of my plurality.

The original supports of my CoG were King Cobras for the longest time, a species of snake that despite its name, hood, and venom, is not actually a cobra. The presence of the Eastern Coral Snake, which is in the family of true cobras even despite its lack of a hood to threat display with, is meant to be something of an honorary hat tip to the previous support and something of a playful inversion on it while still retaining the fundamental concept.

Kingsnakes are also relevant to me on a personal level: my introduction to snakes and their importance to my sense of self started with my family's two California Kingsnakes (one of who was a little asshole, and the other of who was a sweetheart and gentlesnake). They weren't the last or only snakes my family ended up having as pets, but they were my first conscious introduction to reptiles and I loved them with all my heart. The Scarlet Kingsnake is meant to be a small shout-out to their influence on me.

Sunflowers are meant to represent longevity, in recognition of the historical prevalence of non-binary genders and in reference to the fact that I’ve identified as nonbinary for nearly 10 years now. They are, by far, my favorite flower of all time and something I've used to represent myself for many years. For the bottom sunflower supports I used specifically Helianthus angustifolius, or the Swamp Sunflower, and Helianthus annuus, or the American Giant Sunflower. The Swamp Sunflower is, as you can guess, native to my home state of Florida and something I grew up alongside-- they're tenacious plants that can grow up to 8 ft. tall and in huge bushes, but the flowers themselves are quite small! I'm hardy in the same way. American Giants are my favorite kind of sunflower, and are inspiring in how large and in charge they can be. They're bright, sunny, and completely obnoxious, which are all things I can relate to and which I sometimes flaunt my gender as.

Primula meadia, more commonly known as the American Cowslip or "Gentlemen and Ladies," represents divinity and beauty in the language of flowers. These are references to my folcinteric identity, and the ways my nonhumanity often play into concepts of death and divinity. The fact that the flowers are also called "Gentlemen and Ladies" is also very funny to me, as around people who understand my gender identity my pronoun set tends to default to, "whatever makes the joke land," and when I had very first come out as a teenager my public-use pronoun set was "he, or she, or they, or whatever." It's changed since then, but it's a nice reference none the less.

The Tyrannosaurus rex skull is a reference to my alterhumanity as well. Skulls play a major role for me in my nonhumanity, as my primary identity is as a wolf skull-faced canine psychopomp; but T-rexes have an important place in my heart and in my sense of "self." One of my first tattoos to make my body feel less like a house and more like a home was a T-rex skull; one of the only things I managed to take from my family's home when they kicked me out at 18 was my cherished holiday ornament of a golden t-rex skeleton from the Field Museum in Chicago; I even regularly have fictionflickers as an Anjanath currently, which is shaping my nonhumanity and how I directly talk about myself with others.

The Charge (Triheaded Dragon):

The charge is golden to match the Field's outlining colors and refer back to the fact that although this dragon is meant to represent my multiplicity and plurality, this coat of gender is still very much in reference to me singularly rather than necessarily all of us together, even where things may get a bit muddled.

The tri-headed dragon references back to how our system is largely draconic and entirely nonhuman. Our system now has five members rather than four, but I elected to keep it tri-headed as a reminder of the change that the system has gone through over the years. Our shared experiences and understandings of one another's gender identities affect each other in unique and amazing ways, and I can't say that my systemmates haven't helped me become the person I am today. I wouldn't have it any other way.

The Motto

The bottom banner reads, "And the universe said, "I love you."" in reference to the Minecraft ending poem. It's a line that's struck a chord in me over the years. My gender is more and more about finding my place in the universe, engaging in self-love and self-understanding, and reflecting myself as who I really am to those around me with hopes and promises that they'll still find me lovable, if not despite then ideally because of my individuality and uniqueness.

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bats buzz like hornets to scare away predators | Science

The whimpering buzz of a wasp suffices to send out a number of us running for the hills. Now, it appears that a person crafty types has actually utilized that hostility to its benefit. Researchers discovered higher mouse-eared bats simulate the buzzing noise of stinging bugs like wasps, most likely to scare off predators.

“This is a fascinating study,” states David Pfennig, an evolutionary biologist at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, who studies animal mimicry however who was not included with the work.

Nature is loaded with examples of tricky animals and plants mimicing the characteristics of other organisms. The harmless scarlet kingsnake (Lampropeltis elapsoides), for instance, has actually embraced the red-and-black stripes of the precariously poisonous coral snake (Micrurus fulvius).

But there aren’t lots of kept in mind circumstances of acoustic mimicry, Pfennig states, likely since they’re difficult to research study, not always since they don’t exist. “We are a very visually oriented species, and there are a lot of sounds we can’t hear as humans.”

Danilo Russo came across among these by mishap. An ecologist at the University of Naples Federico II, he was performing fieldwork in southeastern Italy more than 2 years back when he snagged some higher mouse-eared bats (Myotis myotis). The types is native to Europe and about the size of a home mouse. Every time Russo went to get the animals and eliminate them from his internet, “they buzzed like wasps or hornets,” he states. It appeared like some sort of defense reaction, he discusses.

One of the mouse-eared bats’ greatest predators are owls, which frequently live in the tree nooks or rock crevices that wasps, hornets, and other buzzing, stinging bugs hole up in. It happened to Russo that the bats may be buzzing to simulate bees and send out owls scampering away. But it took him numerous years to discover the best bat specialists to aid respond to the concern.

Play Pause

Skip in reverseGo 10 seconds backwards Skip forwardsGo 10 seconds forward

Wildlife Research Unit/Department of Agriculture/University of Naples Federico II

Once they collaborated, the scientists tape-recorded the bats’ buzzing in the wild with microphones. They then utilized a computer system program to compare the noises with those made naturally by honey bees (Apis mellifera) and European hornets (Vespa crabro), which share environment with both bats and owls. The program was just able to compare the bats and the bugs about half of the time, an indication the buzzes are acoustically comparable.

The researchers then established an experiment in the laboratory to test predators’ actions to the buzz. They played both the bat and the insect recordings, in addition to a control noise from a various nonbuzzing bat types, for 8 barn owls (Tyto alba) and 8 tawny owls (Strix aluco), which nest in the exact same crevices as the stinging bugs. Half of the owls were raised in captivity, whereas half were wild-caught. The group categorized the owls’ responses to each noise, keeping in mind whether they attempted to escape, attack, or check the speaker releasing the buzz playback.

The birds responded regularly to both the bat and the bug sounds, darting away from the speaker in reaction to the buzzing. The wild owls had a more powerful reaction to the noises, perhaps since of their previous direct exposure to stinging bugs, Russo states. Some attempted to fly away from the sound, whereas none of the captive owls attempted to install a real escape. The finding is the first known case of a mammal mimicking a sound made by an insect species, the scientists report today in Current Biology.

Pfennig questions how susceptible the owls in fact are to bee or hornet stings in the wild. “Owls are nocturnal, bees are not,” he states. The authors acknowledge they don’t understand how frequently the birds get stung, however anecdotes point to an adversarial relationship. For example, when hornets colonize nest boxes set out for owls to live in, Russo states, “the birds do not even attempt to explore them, not to mention nest there.”

Despite this, the research study is still “really cool,” Pfennig states. “Mimicry is one of the best examples of natural selection in action.”

New post published on: https://livescience.tech/2022/05/10/bats-buzz-like-hornets-to-scare-away-predators-science/

0 notes

Photo

Todays Snake Is:

The Scarlet Kingsnake (Lampropeltis elapsoides) is a nonvenomous species native to the southeastern United States. These animals are one of the best-known coral mimics, having a pattern very similar to the Eastern Coral Snake (Micrurus fulvius), which helps protect it from predators.

(x)

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some bats can imitate the sound of buzzing hornets to scare off owls, researchers say. The discovery is the first documented case of a mammal mimicking an insect to deter predators.

Many animals copy other creatures in a bid to make themselves seem less palatable to predators. Most of these imitations are visual. North America’s non-venomous scarlet kingsnake (Lampropeltis elapsoides), for instance, has evolved to have similar colour-coding to the decidedly more dangerous eastern coral snake (Micrurus fulvius).

Now, a study comparing the behaviour of owls exposed to insect and bat noises suggests that greater mouse-eared bats (Myotis myotis) might be among the few animals to have weaponized another species’ sound, says co-author Danilo Russo, an animal ecologist at the University of Naples Federico II in Italy.

93 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Eastern Milksnake (Lampropeltis triangulum triangulum)

Scarlet King Snake (Lampropeltis elapsoides)

Red Milksnake (Lampropeltis triangulum syspila)

Photos by Peter Paplanus

95 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Scarlet Kingsnake

Lampropeltis Elapsoides

Source: Here

#snake#snakes#reptile#reptiles#animal#animals#pet#pets#nature#wildlife#cool#interesting#aesthetic#aesthetics#beautiful#pretty#snek#sneks#kingsnake#kingsnakes#scarlet snake#scarlet kingsnake

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

Herp Taxa

CNAH: North American Herpetofauna: Reptilia: Squamata (part)

Names that differ in any way from those published in the most most recent joint Society names list (see introduction)

About CNAH have their Standard English name shown in green.

Statement

of Purpose Reptilia Laurenti, 1768 - Reptiles

Squamata (part) Oppel, 1811 - Snakes

CNAH Board

Boidae Gray, 1842 - Boas

CNAH Officers Charina Gray, 1849 - Rubber Boas

C. bottae (Blainville, 1835) - Northern Rubber Boa

CNAH Awards

C. umbratica Klauber, 1943 - Southern Rubber Boa

CNAH Donors Lichanura Cope, 1861 - Rosy Boas

L. orcutti (Stejneger 1889) - Northern Three-lined Boa

JNAH

L. trivirgata (Cope, 1861) - Rosy Boa

Contemporary

Herpetology

Colubridae Oppel, 1811 - Harmless Egg-Laying Snakes

Contact Us

Arizona Kennicott, 1859 - Glossy Snakes

A. elegans Kennicott, in Baird, 1859 - Glossy Snake

A. e. arenicola Dixon, 1960 - Texas Glossy Snake

A. e. candida Klauber, 1946 - Mohave Glossy Snake

A. e. eburnata Klauber, 1946 - Desert Glossy Snake

A. e. elegans Kennicott, in Baird, 1859 - Kansas Glossy Snake

A. e. noctivaga Klauber, 1946 - Arizona Glossy Snake

A. e. occidentalis Blanchard, 1924 - California Glossy Snake

A. e. philipi Klauber, 1946 - Painted Desert Glossy Snake

Bogertophis Dowling & Price, 1988 - Desert Ratsnakes

B. rosaliae (Mocquard, 1899) - Baja California Ratsnake

B. subocularis (Brown, 1901) - Trans-Pecos Ratsnake

B. s. subocularis (Brown, 1901) - Northern Trans-Pecos Ratsnake

Cemophora Cope, 1860 - Scarletsnakes

C. coccinea (Blumenbach, 1788) - Scarletsnake

C. lineri Williams, Brown & Wilson, 1966 - Texas Scarletsnake

Coluber Linnaeus, 1758 - North American Racers, Coachwhips, and Whipsnakes

C. constrictor Linnaeus, 1758 - North American Racer

C. c. anthicus (Cope, 1862) - Buttermilk Racer

C. c. constrictor Linnaeus, 1758 - Northern Black Racer

C. c. etheridgei Wilson, 1970 - Tan Racer

C. c. flaviventris Say in James, 1822 - Eastern Yellow-bellied Racer

C. c. foxii (Baird and Girard, 1853) - Blue Racer

C. c. helvigularis Auffenberg, 1955 - Brown-chinned Racer

C. c. latrunculus Wilson, 1970 - Black-masked Racer

C. c. mormon Baird & Girard, 1852 - Western Yellow-bellied Racer

C. c. oaxaca (Jan, 1863) - Mexican Racer

C. c. paludicola Auffenberg & Babbitt, 1953 - Everglades Racer

C. c. priapus Dunn & Wood, 1939 - Southern Black Racer

Drymarchon Fitzinger, 1843 - Indigo Snakes

D. couperi (Holbrook, 1842) - Eastern Indigo Snake

D. melanurus (Duméril, Bibron & Duméril, 1853) - Central American Indigo Snake

D. m. erebennus (Cope, 1860) - Texas Indigo Snake

Drymobius Fitzinger, 1843 - Neotropical Racers

D. margaritiferus (Schlegel, 1837) - Speckled Racer

D. m. margaritiferus (Schlegel, 1837) - Northern Speckled Racer

Ficimia Gray, 1849 - Eastern Hook-nosed Snakes

F. streckeri Taylor, 1931 - Tamaulipan Hook-nosed Snake

Gyalopion Cope, 1860 - Western Hook-nosed Snakes

G. canum Cope, 1861 “1860” - Chihuahuan Hook-nosed Snake

G. quadrangulare (Günther, 1893 in Salvin and Godman, 1885-1902) - Thornscrub Hook-nosed Snake

Lampropeltis Fitzinger, 1843 - Kingsnakes

L. alterna (Brown, 1901) - Gray-banded Kingsnake

L. annulata Kennicott, 1860 - Mexican Milksnake

L. californiae (Blainville, 1835) - California Kingsnake

L. calligaster (Harlan, 1827) - Prairie Kingsnake

L. elapsoides (Holbrook, 1838) - Scarlet Kingsnake

L. extenuata (Brown, 1890) - Short-tailed Kingsnake

L. gentilis (Baird & Girard, 1853) - Western Milksnake

L. getula (Linnaeus, 1766) - Eastern Kingsnake

L. holbrooki Stejneger, 1902 - Speckled Kingsnake

L. knoblochi (Taylor, 1940) - Knobloch’s Mountain Kingsnake

L. nigra (Yarrow, 1882) - Eastern Black Kingsnake

L. occipitolineata Price, 1987 - South Florida Mole Kingsnake

L. pyromelana (Cope, 1866) - Pyro Mountain Kingsnake

L. p. infralabialis Tanner, 1953 - Utah Mountain Kingsnake

L. p. pyromelana (Cope, 1867) - Arizona Mountain Kingsnake

L. rhombomaculata (Holbrook, 1840) - Mole Kingsnake

L. splendida (Baird & Girard, 1853) - Desert Kingsnake

L. triangulum (Lacépède, 1789) - Eastern Milksnake

L. zonata (Blainville, 1835) - California Mountain Kingsnake

Masticophis Baird & Girard, 1853 - Whipsnakes

M. bilineatus Jan, 1863 - Sonoran Whipsnake

M. flagellum (Shaw, 1802) - Coachwhip

M. f. cingulum (Lowe & Woodin, 1954) - Sonoran Coachwhip

M. f. flagellum Shaw, 1802 - Eastern Coachwhip

M. f. lineatulus (Smith, 1941) - Lined Coachwhip

M. f. piceus (Cope, 1892) - Red Racer

M. f. ruddocki (Brattstrom & Warren, 1953) - San Joaquin Coachwhip

M. f. testaceus Say in James, 1822 - Western Coachwhip

M. fuliginosus (Cope, 1895) - Baja California Coachwhip

M. lateralis (Hallowell, 1853) - Striped Racer

M. l. euryxanthus (Riemer, 1954) - Alameda Striped Racer

M. l. lateralis (Hallowell, 1853) - California Striped Racer

M. schotti (Baird & Girard, 1853) - Schott''s Whipsnake

M. s. ruthveni (Ortenburger, 1923) - Ruthven''s Whipsnake

M. s. schotti (Baird & Girard, 1853) - Schott’s Striped Whipsnake

M. taeniatus (Hallowell, 1852) - Striped Whipsnake

M. t. girardi (Stejneger & Barbour, 1917) - Central Texas Whipsnake

M. t. taeniatus (Hallowell, 1852) - Desert Striped Whipsnake

Opheodrys Fitzinger, 1843 - Greensnakes

O. aestivus (Linnaeus, 1766) - Rough Greensnake

O. a. aestivus (Linnaeus, 1766) - Northern Rough Greensnake

O. a. carinatus Grobman, 1984 - Florida Rough Greensnake

O. vernalis (Harlan, 1827) - Smooth Greensnake

Oxybelis Wagler, 1830 - American Vinesnakes

O. aeneus (Wagler, 1824) - Brown Vinesnake

Pantherophis Fitzinger, 1843 - North American Ratsnakes

P. alleghaniensis (Holbrook, 1836) - Eastern Ratsnake

P. bairdi (Yarrow, 1880) - Baird's Ratsnake

P. emoryi (Baird & Girard, 1853) - Great Plains Ratsnake

P. guttatus (Linnaeus, 1766) - Red Cornsnake

P. obsoletus (Say in James, 1822) - Western Ratsnake

P. ramspotti (Crother, White, Savage, Eckstut, Graham & Gardner, 2011) - Western Foxsnake

P. slowinskii (Burbrink, 2002) - Slowinski's Cornsnake

P. spiloides (Duméril, Bibron & Duméril, 1854) - Gray Ratsnake

P. vulpinus (Baird & Girard, 1853) - Eastern Foxsnake

Phyllorhynchus Stejneger, 1890 - Leaf-nosed Snakes

P. browni Stejneger, 1890 - Saddled Leaf-nosed Snake

P. decurtatus (Cope, 1868) - Spotted Leaf-nosed Snake

Pituophis Holbrook, 1842 - Bullsnakes, Pinesnakes, and Gophersnakes

P. catenifer (Blainville, 1835) - Gophersnake

P. c. affinis Hallowell, 1852 - Sonoran Gophersnake

P. c. annectens Baird & Girard, 1853 - San Diego Gophersnake

P. c. catenifer (Blainville, 1835) - Pacific Gophersnake

P. c. deserticola Stejneger, 1893 - Great Basin Gophersnake

P. c. pumilus Klauber, 1946 - Santa Cruz Gophersnake

P. c. sayi (Schlegel, 1837) - Bullsnake

P. melanoleucus (Daudin, 1803) - Eastern Pinesnake

P. m. lodingi Blanchard, 1924 - Black Pinesnake

P. m. melanoleucus (Daudin, 1803) - Northern Pinesnake

P. m. mugitus Barbour, 1921 - Florida Pinesnake

P. ruthveni Stull, 1929 - Louisiana Pinesnake

Rhinocheilus Baird & Girard, 1853 - Long-nosed Snakes

R. lecontei Baird & Girard, 1853 - Long-nosed Snake

Salvadora Baird & Girard, 1853 - Patch-nosed Snakes

S. grahamiae Baird & Girard, 1853 - Eastern Patch-nosed Snake

S. g. grahamiae Baird & Girard, 1853 - Mountain Patch-nosed Snake

S. g. lineata Schmidt, 1940 - Texas Patch-nosed Snake

S. hexalepis (Cope, 1866) - Western Patch-nosed Snake

S. h. deserticola Schmidt, 1940 - Big Bend Patch-nosed Snake

S. h. hexalepis (Cope, 1866) - Desert Patch-nosed Snake

S. h. mojavensis Bogert, 1945 - Mohave Patch-nosed Snake

S. h. virgultea Bogert, 1935 - Coast Patch-nosed Snake

Senticolis Dowling & Fries, 1987 - Green Ratsnakes

S. triaspis (Cope, 1866) - Green Ratsnake

S. t. intermedia (Boettger, 1883) - Northern Green Ratsnake

Sonora Baird & Girard, 1853 - North American Groundsnakes

S. annulata (Baird, 1859 “1858”) - Colorado Desert Shovel-nosed Snake

S. episcopa (Kennicott 1859) - Great Plains Groundsnake

S. occipitalis (Hallowell, 1854) - Western Shovel-nosed Snake

S. o. klauberi (Stickel, 1941) - Tucson Shovel-nosed Snake

S. o. occipitalis (Hallowell, 1854) - Mohave Shovel-nosed Snake

S. o. talpina Klauber, 1951 - Nevada Shovel-nosed Snake

S. palarostris (Klauber, 1937) - Sonoran Shovel-nosed Snake

S. p. organica Klauber, 1951 - Organ Pipe Shovel-nosed Snake

S. semiannulata Baird & Girard, 1853 - Western Groundsnake

S. straminea (Cope, 1860) - Variable Sandsnake

S. taylori (Boulenger, 1894) - Southern Texas Groundsnake

Tantilla Baird & Girard, 1853 - Black-headed, Crowned, and Flat-headed Snakes

T. atriceps (Günther, 1895 in Salvin and Godman, 1885-1902) - Mexican Black-headed Snake

T. coronata Baird & Girard, 1853 - Southeastern Crowned Snake

T. cucullata Minton, 1956 - Trans-Pecos Black-headed Snake

T. gracilis Baird & Girard, 1853 - Flat-headed Snake

T. hobartsmithi Taylor, 1937 - Smith’s Black-headed Snake

T. nigriceps Kennicott, 1860 - Plains Black-headed Snake

T. oolitica Telford, 1966 - Rim Rock Crowned Snake

T. planiceps (Blainville, 1835) - Western Black-headed Snake

T. relicta Telford, 1966 - Florida Crowned Snake

T. r. neilli Telford, 1966 - Central Florida Crowned Snake

T. r. pamlica Telford, 1966 - Coastal Dunes Crowned Snake

T. r. relicta Telford, 1966 - Peninsula Crowned Snake

T. wilcoxi Stejneger, 1902 - Chihuahuan Black-headed Snake

T. yaquia Smith, 1942 - Yaqui Black-headed Snake

Trimorphodon Cope, 1861 - Lyresnakes

T. lambda Cope, 1886 - Sonoran Lyresnake

T. lyrophanes (Cope, 1860) - California Lyresnake

T. vilkinsonii Cope, 1886 - Texas Lyresnake

Crotalidae Oppel, 1811 - Pitvipers

Agkistrodon Palisot de Beauvois, 1799 - American Moccasins

A. conanti Gloyd, 1969 - Florida Cottonmouth

A. contortrix (Linnaeus, 1766) - Eastern Copperhead

A. laticinctus (Gloyd & Conant, 1934) - Broad-banded Copperhead

A. piscivorus (Lacépède, 1789) - Northern Cottonmouth

Crotalus Linnaeus, 1758 - Rattlesnakes

C. adamanteus Palisot de Beauvois, 1799 - Eastern Diamond-backed Rattlesnake

C. atrox Baird & Girard, 1853 - Western Diamond-backed Rattlesnake

C. cerastes Hallowell, 1854 - Sidewinder

C. c. cerastes Hallowell, 1854 - Mohave Desert Sidewinder

C. c. cercobombus Savage & Cliff, 1953 - Sonoran Sidewinder

C. c. laterorepens Klauber, 1944 - Colorado Desert Sidewinder

C. cerberus (Coues, 1875) - Arizona Black Rattlesnake

C. horridus Linnaeus, 1758 - Timber Rattlesnake

C. lepidus (Kennicott, 1861) - Rock Rattlesnake

C. l. klauberi Gloyd, 1936 - Banded Rock Rattlesnake

C. l. lepidus (Kennicott, 1861) - Mottled Rock Rattlesnake

C. molossus Baird & Girard, 1853 - Black-tailed Rattlesnake

C. m. molossus Baird & Girard, 1853 - Northern Black-tailed Rattlesnake

C. oreganus Holbrook, 1840 - Western Rattlesnake

C. o. abyssus Klauber, 1930 - Grand Canyon Rattlesnake

C. o. concolor Woodbury, 1929 - Midget Faded Rattlesnake

C. o. helleri Meek, 1905 - Southern Pacific Rattlesnake

C. o. lutosus Klauber, 1930 - Great Basin Rattlesnake

C. o. oreganus Holbrook, 1840 - Northern Pacific Rattlesnake

C. ornatus Hallowell 1954 - Eastern Black-tailed Rattlesnake

C. pricei Van Denburgh, 1895 - Twin-spotted Rattlesnake

C. p. pricei Van Denburgh, 1895 - Western Twin-spotted Rattlesnake

C. pyrrhus (Cope, 1867 “1866”) - Southwestern Speckled Rattlesnake

C. ruber Cope, 1892 - Red Diamond Rattlesnake

C. scutulatus (Kennicott, 1861) - Mohave Rattlesnake

C. s. scutulatus (Kennicott, 1861) - Northern Mohave Rattlesnake

C. stephensi Klauber, 1930 - Panamint Rattlesnake

C. tigris Kennicott, 1859 - Tiger Rattlesnake

C. viridis (Rafinesque, 1818) - Prairie Rattlesnake

C. willardi Meek, 1905 - Ridge-nosed Rattlesnake

C. w. obscurus Harris, 1974 - New Mexico Ridge-nosed Rattlesnake

C. w. willardi Meek, 1905 - Arizona Ridge-nosed Rattlesnake

Sistrurus Garman, 1883 - Massasauga and Pygmy Rattlesnakes

S. catenatus (Rafinesque, 1818) - Eastern Massasauga

S. miliarius (Linnaeus, 1766) - Pygmy Rattlesnake

S. m. barbouri Gloyd, 1935 - Dusky Pygmy Rattlesnake

S. m. miliarius (Linnaeus, 1766) - Carolina Pygmy Rattlesnake

S. m. streckeri Gloyd, 1935 - Western Pygmy Rattlesnake

S. tergeminus (Say in James, 1822) - Western Massasauga

S. t. edwardsii (Baird & Girard, 1853) - Desert Massasauga

S. t. tergeminus (Say in James, 1822) - Prairie Massasauga

Dipsadidae Bonaparte, 1838 - Rear-Fanged Snakes

Carphophis Gervais, 1843 - North American Wormsnakes

C. amoenus (Say, 1825) - Common Wormsnake

C. a. amoenus (Say, 1825) - Eastern Wormsnake

C. a. helenae (Kennicott, 1859) - Midwestern Wormsnake

C. vermis (Kennicott, 1859) - Western Wormsnake

Coniophanes Hallowell, 1860 - Black-striped Snakes

C. imperialis (Baird, 1859) - Regal Black-striped Snake

C. i. imperialis (Baird, 1859) - Tamaulipan Black-striped Snake

Contia Baird & Girard, 1853 - Sharp-tailed Snakes

C. longicauda Feldman & Hoyer, 2010 - Forest Sharp-tailed Snake

C. tenuis (Baird & Girard, 1852) - Common Sharp-tailed Snake

Diadophis Baird & Girard, 1853 - Ring-necked Snakes

D. punctatus (Linnaeus, 1766) - Ring-necked Snake

D. p. acricus Paulson, 1968 - Key Ring-necked Snake

D. p. amabilis Baird & Girard, 1853 - Pacific Ring-necked Snake

D. p. arnyi Kennicott, 1859 - Prairie Ring-necked Snake

D. p. edwardsii (Merrem, 1820) - Northern Ring-necked Snake

D. p. modestus Bocourt, 1866 - San Bernardino Ring-necked Snake

0 notes

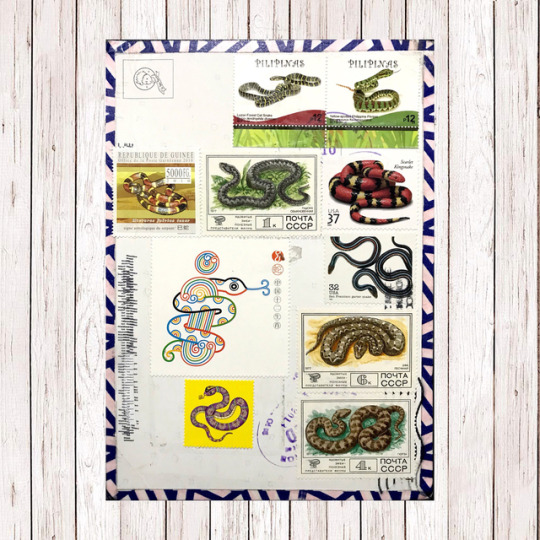

Photo

#chaincard theme: Snakes 🐍 Travel time: 01.10.2018 - 04.20.2018 Countries: PH🇵🇭-US🇺🇸-BY🇧🇾-RU🇷🇺-CN🇨🇳-🏡 Thank you @allochka_pictures for hosting ... Stamps: 🇵🇭: Luzon Forest Cat Snake (Boiga dendrophila divergens) Yellow-Spotted Philippine Pitviper (Trimeresurus flavomaculatus) Endemic Snakes of the Philippines - 08.16/2017 🇺🇸: Scarlet kingsnake (Lampropeltis elapsoides) - 10.07.2003 San Francisco garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis tetrataenia) - 10.02.1996 🇧🇾: Coral snake (Micrurus fulvius tener) - Astrological Sign of the Snake - Guinea 🇬🇳 Stamp - 10.10.25 Adder (Vipera berus) - Fauna of USSR - 12.16.177 🇷🇺: Saw-scaled Viper (Echis carinatus) Levantine Viper (Vipera lebetina) Fauna of USSR - 12.16.177 🇨🇳: Stylized snakes - Sheet gutter only ... #adcstamps #adcchain #philately #chaincardproject #Snake #snakes #snakeCC #philategram #sellos #correos #timbres #PHLPost #USPS #ChinaPost #PochtaRu #Guinea #USSR #postagestamp #collection #kolektorz (at Snake)

#philately#chaincard#snakecc#collection#chinapost#phlpost#postagestamp#snakes#philategram#chaincardproject#ussr#correos#timbres#kolektorz#snake#pochtaru#adcchain#usps#guinea#sellos#adcstamps

0 notes

Photo

Micrurus fulvius

Micrurus fulvius (Eastern coral snake, common coral snake, American cobra, more) is a species of venomous elapid snake endemic to the southeastern United States. It should not be confused with the scarlet snake (Cemophora coccinea) or scarlet kingsnake (Lampropeltis elapsoides), which are harmless mimics. No subspecies are currently recognized.

More details Android, Windows

0 notes

Text

Scarlet Kingsnake (Lampropeltis elapsoides), family Colubridae, Florida, USA

Coral snake mimic.

photograph by Luke Smith

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bats buzz like hornets to scare away predators | Science

The whining buzz of a wasp is enough to send many of us running for the hills. Now, it seems that one crafty species has used that aversion to its advantage. Researchers found greater mouse-eared bats mimic the buzzing sound of stinging insects like wasps, likely to scare off predators.

“This is a fascinating study,” says David Pfennig, an evolutionary biologist at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, who studies animal mimicry but who was not involved with the work.

Nature is replete with examples of sneaky animals and plants imitating the traits of other organisms. The innocuous scarlet kingsnake (Lampropeltis elapsoides), for example, has adopted the red-and-black stripes of the dangerously venomous coral snake (Micrurus fulvius).

But there aren’t many noted instances of acoustic mimicry, Pfennig says, likely because they’re hard to study, not necessarily because they don’t exist. “We are a very visually oriented species, and there are a lot of sounds we can’t hear as humans.”

Danilo Russo happened upon one of these by accident. An ecologist at the University of Naples Federico II, he was conducting fieldwork in southeastern Italy more than 2 decades ago when he snagged some greater mouse-eared bats (Myotis myotis). The species is native to Europe and about the size of a house mouse. Every time Russo went to grab the animals and remove them from his nets, “they buzzed like wasps or hornets,” he says. It seemed like some sort of defense mechanism, he explains.

One of the mouse-eared bats’ biggest predators are owls, which commonly live in the tree nooks or rock crevices that wasps, hornets, and other buzzing, stinging insects hole up in. It occurred to Russo that the bats might be buzzing to mimic bees and send owls scurrying away. But it took him several years to find the right bat experts to help answer the question.

Play Pause

Skip backwardsGo ten seconds backward Skip forwardsGo ten seconds forward

Wildlife Research Unit/Department of Agriculture/University of Naples Federico II

Once they teamed up, the researchers recorded the bats’ buzzing in the wild with microphones. They then used a computer program to compare the sounds with those made naturally by honey bees (Apis mellifera) and European hornets (Vespa crabro), which share habitat with both bats and owls. The program was only able to distinguish between the bats and the bugs about half of the time, a sign the buzzes are acoustically similar.

The scientists then set up an experiment in the lab to test predators’ responses to the buzz. They played both the bat and the insect recordings, as well as a control sound from a different nonbuzzing bat species, for eight barn owls (Tyto alba) and eight tawny owls (Strix aluco), which nest in the same crevices as the stinging insects. Half of the owls were raised in captivity, whereas half were wild-caught. The team classified the owls’ reactions to each sound, noting whether they tried to escape, attack, or inspect the speaker emitting the buzz playback.

The birds reacted consistently to both the bat and the bug sounds, darting away from the speaker in response to the buzzing. The wild owls had a stronger response to the sounds, possibly because of their prior exposure to stinging insects, Russo says. Some tried to fly away from the noise, whereas none of the captive owls tried to mount an actual escape. The finding is the first known case of a mammal mimicking a sound made by an insect species, the researchers report today in Current Biology.

Pfennig wonders how vulnerable the owls actually are to bee or hornet stings in the wild. “Owls are nocturnal, bees are not,” he says. The authors acknowledge they don’t know how often the birds get stung, but anecdotes point to an adversarial relationship. For example, when hornets colonize nest boxes set out for owls to live in, Russo says, “the birds do not even attempt to explore them, not to mention nest there.”

Despite this, the study is still “really cool,” Pfennig says. “Mimicry is one of the best examples of natural selection in action.”

New post published on: https://livescience.tech/2022/05/10/bats-buzz-like-hornets-to-scare-away-predators-science/

0 notes

Photo

Scarlet Kingsnake

Lampropeltis Elapsoides

Source: Here

#snake#snakes#reptile#reptiles#animal#animals#pet#pets#nature#wildlife#cool#interesting#aesthetic#aesthetics#beautiful#pretty#snek#sneks#kingsnake#kingsnakes#scarlet kingsnakes#scarlet kingsnake

111 notes

·

View notes