#mariana dimópulos

Text

La obra proviene del caos. Esa superficie se ve como la mera armonía, la mera expresión, el puro decir de la obra de arte. Llamémosla: la armonía parlante. Ante esta superficie que dice y avanza, contra este flujo de lo dicho y lo decible que participa, por ende, de lo aparente, solo queda la detención de lo que carece de expresividad. Otra vez, hay que frenar. Para que lo inexpresivo se vuelva una puerta. Esto se sustrae de todo carácter temático y de todo argumento. Y es este reverso de lo decible que hace posible lo eterno de la obra.

—Mariana Dimópulos, «La crítica» en Carrusel Benjamin.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

She ranted about all those people in the world who didn't believe in authentic love - which is hard like a diamond but cannot be polished.

Imminence, Mariana Dimópulos

0 notes

Text

Coetzee contra el inglés

¿Qué motivos empujan a un autor que domina la lengua inglesa a renegar de ella?

Escena de la película Lost in Translation (Sofia Coppola, 2003).

Escrito por Pedro Tena

Hace unas pocas semanas tuve la oportunidad de asistir a una charla abierta al público que el escritor sudafricano J.M. Coetzee dio con ocasión de su reciente residencia en el Prado, en Madrid, al alimón con Mariana Dimópulos,…

View On WordPress

#Authenticité#Bilingüismo#Castellano#Diversité#Escrita#Français#Identité#J.M. Coetzee#Lenguaje#Literatura#Música#Memoria#Poésie#Política#Prix#Samuel Beckett#Sociedade#Tecnologías#Tradução

0 notes

Text

Illustration by Luis Mazón

J. M. Coetzee’s War Against Global English

What lies behind the celebrated South African writer’s decision to publish his latest novel in Spanish before making it available in English?

— By Colin Marshall | December 8, 2022

It may come as a surprise to most of J. M. Coetzee’s readers that he published a new novel in August. “El Polaco,” which is set in Barcelona, is about a romantic entanglement between Witold, a concert pianist of about seventy known for his controversial interpretations of Chopin, and Beatriz, a music-loving Catalan woman in her forties who assists him during his stay in the city. Fired more by mind than body, the two attempt to conduct their affair using the kind of stilted, colorless “global English” to which international communication so often defaults. Apart from an initial carnal encounter, their romance takes place in large part by correspondence: Witold writes Beatriz poems, but, with English verse lying beyond his grasp, he does so in his native Polish. Beatriz engages a translator in order not just to understand but evaluate Witold’s poems, which she gives modest marks.

A short novel, restrained even by Coetzee’s standards, “El Polaco” is made up entirely of numbered paragraphs, some of which consist of a single sentence. The first: “La mujer es la primera en causarle problemas, seguida pronto por el hombre.” Witold is el hombre; Beatriz is la mujer. But occasional slips in the dissimulating, pseudo-objective voice of the text suggest that she’s also the narrator. Another sign of her role is the book’s language: though first written in English, “El Polaco” has so far only been published in a Spanish translation. The translator, Mariana Dimópulos, played an unusually active role in the novel’s creation: Coetzee has spoken of incorporating her suggestions about how a woman like Beatriz would think, speak, and act back into the original manuscript.

“El Polaco” is the second of Coetzee’s novels to appear in Spanish first, but he began privileging translations much earlier in his career: in the past twenty years, he’s seen to it that many of his books be made available in Dutch before any other language. Fêted in Amsterdam in 2010, Coetzee expressed appreciation at being “read in a language in which I feel myself to be a somewhat more humorous writer than in the original English.” “Humorous” is far less commonly applied to his writing than adjectives like “cold,” “austere,” “rigorous,” “spare”; Martin Amis famously described his style as “predicated on transmitting absolutely no pleasure.” But to his enthusiasts Coetzee transmits a great deal of pleasure—in his outwardly severe, circumscribed manner—and exhibits an abiding if vanishingly subtle sense of humor. I would rank his “Diary of a Bad Year” (best known for its unconventional form, with separate texts stacked vertically on the page) as the funniest novel of the twenty-first century, despite having read only the English original, not the presumably funnier Dutch translation.

Coetzee’s connection with Dutch (a language whose literature he also translates into English), comes by way of its South African descendant. The author “has a deep relationship with the Afrikaans language,” his biographer David Attwell writes. Yet whether Coetzee can be counted among its native speakers is unclear. The grandson of “Afrikaans-speaking anglophiles,” he grew up using English at home with his mother and father; “both parents would have associated English with high culture and Afrikaans with low,” though other relatives mixed the two freely. (In the autobiographical “Boyhood,” Coetzee writes of suddenly coming into bilingualism: “He still remembers how he burst in on his mother, shouting, ‘Listen! I can speak Afrikaans!’ ”) The result of such an upbringing, and his subsequent stretches in England and the United States, is that, “to an English-speaking South African ear, Coetzee’s spoken English is unlocatable.”

Never has Coetzee enjoyed an uncomplicated relationship with language, least of all the English language. “El Polaco” comes nearly half a century after his début novel, “Dusklands,” which was published in his native South Africa in 1974. That book, as Coetzee put it a few years ago during an interview in Madrid, was written by a young man “born in South Africa, of an ethnicity which is a little hard to define,” with the appearance of an Afrikaner but without “several of the characteristic properties” of Afrikaner identity. “This young man starts writing fiction in an acquired language—namely, English. He finds a publisher in South Africa, a small publisher.” His book sells a few thousand copies and wins local prizes, “but he’s got larger ambitions. His ambition is to be published in ‘the real world,’ which to him means London, but particularly it means New York”—and, in any case, publishing in English rather than Afrikaans.

In a 2019 interview at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Coetzee himself said that “as a child, as a young man, as a student, I had absolutely no doubt that access to the English language was liberating me from the narrow world view of the Afrikaner.” But maturity has introduced a distance: “I have a good command of English, spoken and written, but more and more it feels to me like the kind of command that a foreigner might have,” he said, in 2018, at the Hay literary festival in Cartagena. “This may be the reason why the English I write is so easily translatable. I’ve worked closely with translators of my books into languages that I know, and it seems to me that the versions that my translators produce are in no way inferior to the original.”

In his work, Coetzee has suggested that his interest in Spanish dates back at least to the early nineteen-sixties. As a fresh University of Cape Town graduate, he moved to London and found work as a computer programmer. The protagonist of his autobiographical novel “Youth,” in that same situation, spends his free time attempting to learn various European languages. “He reads Cesar Vallejo in a dual-language text, reads Nicolas Guillén, reads Pablo Neruda. Spanish is full of barbaric-sounding words whose meaning he cannot even guess at, but that does not matter. At least every letter is pronounced, down to the double r.”

In recent years, Coetzee has become particularly involved with Argentinean literary culture. His relations with that country began late in his life, he said in a 2015 talk at the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires, and “came as a considerable surprise.” From his first trip to Argentina, Coetzee said, he encountered “a reading public that really took books seriously and read books intelligently.” Beginning in the mid-twenty-tens, Coetzee directed a seminar series on literature of the Southern Hemisphere at the Universidad Nacional de San Martín; he has also curated a “personal library” series for the publishing house El Hilo de Ariadna. (His selections include Tolstoy’s “The Death of Ivan Ilyich,” Samuel Beckett’s “Watt,” and Patrick White’s “The Solid Mandala.”) But the major work of his Argentinean period, and clearest literary reflection of his evolving views on language, has been a trilogy of novels: “The Childhood of Jesus,” “The Schooldays of Jesus,” and “The Death of Jesus.”

All three “Jesus” novels were translated into Spanish, though only the third came out in Spanish translation first. They take place in a somewhat abstracted netherworld to which its characters seem to have emigrated from forgotten previous lives. One of these immigrants, a young boy named Davíd—the apparent Christ figure of the title—learns to read the language from a children’s edition of “Don Quixote,” whose story he goes on to preach as a kind of gospel. Coetzee’s own references to Cervantes’s work go back decades, and it’s undeniably tempting (especially given his increasing physical resemblance to its white-bearded hero) to apply the word “quixotic” to his late-career stand against the seemingly unstoppable tide of English. “I resist absolutely the idea that English has become so universal a language that it must be the language of the next life, too,” Coetzee said, at unam. “In these three books, we all have to learn Spanish in order to speak to our neighbors. Basta.”

Coetzee has told the Spanish-speaking press that the Spanish translation of “El Polaco” reflects his intentions more clearly than the original English text does. That he chose to publish the translation first through El Hilo de Ariadna reflects his distrust of the language through which he has become such a venerated figure. “I do not like the way in which English is taking over the world,” he declared, at the Hay literary festival. “I do not like the way in which it crushes the minor languages that it finds in its path. I don’t like its universalist pretensions, by which I mean its uninterrogated belief that the world is as it seems to be in the mirror of the English language. I don’t like the arrogance that this situation breeds in its native speakers. Therefore, I do what little I can to resist the hegemony of the English language.”

In “El Polaco,” the difficulties Witold and Beatriz experience in establishing and maintaining their relationship owe in part to their using a common language of convenience: neither has a perfect command of English, let alone an organic cultural connection to it. Their ostensibly shared language becomes a barrier to intimacy—ultimately an insurmountable one. Even as he writes in English, Coetzee is culturally and intellectually well placed to critique it in this way. The “studied quality” of his speech and prose, as Attwell puts it, “lends credence to his suspicion that English cannot be his mother tongue.” His growing alienation from that language has bought his writing closer to that of Beckett, in the latter’s French period—or to that of Nabokov, whose “feeling for English words is exact,” as Coetzee writes in the notes of one lecture from his university-professor days, “but deliberately remains that of a connoisseur, an outsider.”

The result is global English but one without the imprecision and solecism implied by that label. Out of a desire to better understand the peculiar strengths of Coetzee’s prose—which makes an impact of a kind seldom felt in the writing of native speakers—I’ve spent the past two years retyping the entirety of his autobiographical trilogy, “Boyhood,” “Youth,” and “Summertime.” In South Korea, where I now live, this practice is called pilsa, and its many practitioners use it to improve their writing skills, not only in Korean but also foreign languages, most popularly English. Coetzee would surely grumble at that, but I like to think he’d approve of my own pilsa routine, which also involves retyping the collected works of Borges—in the original, of course. ♦

— The New Yorker

0 notes

Photo

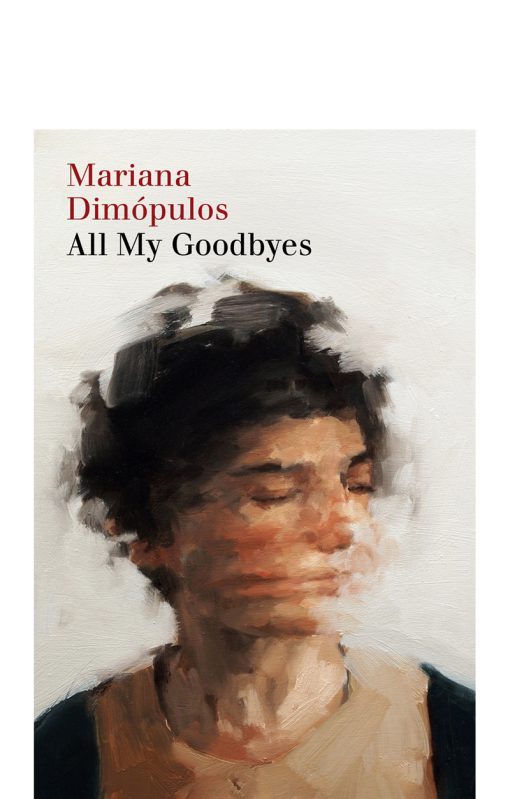

“The narrator of All My Goodbyes [by Mariana Dimópulos, translated by Alice Whitmore], is intensely frustrating to the people around her — she is ever-moving, ever-changing. Whenever things start to seem overwhelmingly normal, familiar, in a place where she lives, she feels the urge to flee and start all over. She’s fled her home of Buenos Aires, she’s fled Berlin, and many a city in between, abandoning people who cared for her, before she comes to a small town in Patagonia where a murder will eventually take place. The storylines cross and turn over one another, the goodbyes overlapping, the arrivals shifting. The enigmatic narrator in her self-imposed isolation and the lyrical, quick place of the novel come together to form a disconcerting novel about feeling lost.”

—review pulled from my list of Argentinian books available in English translation, published for Book Riot.

#all my goodbyes#mariana dimópulos#alice whitmore#women in translation#books in translation#wit month#argentinian literature#my book reviews

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“I believe in those pilgrim years, when staying put was not an option, those years spent in a kind of conspiracy with habit and daily routine, despite myself, but always with a ticket under my arm, or perhaps up my dirty sleeve, always with a passage to somewhere else at the ready. I would arrive with the intention of staying. And even then I wouldn’t stay.” --Mariana Dimópulos, All My Goodbyes (published by Giramondo)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

A second-hand melancholy: Imminence by Mariana Dimópulos

A second-hand melancholy: Imminence by Mariana Dimópulos @GiramondoBooks @alicewhitmore

At the beginning of Argentinian writer Mariana Dimópulos’ unsettling novel Imminence, it is immediately evident that there is something oddly off-balance here, a softly-hued disconnect that instantly sets the tone for one of the most finely realized representations of what it feels like to be oddly out of step with the world around you. The narrator, alone for the first time with her infant son…

View On WordPress

#Alice Whitmore#Argentina#book review#books#Giramondo#Imminence#literature#Mariana Dimópulos#Spanish#translation

1 note

·

View note

Link

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

How I wished I could dismount from the carousel of my life.

Mariana Dimópulos

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mientras que el pensar hace violencia a aquello sobre lo cual ejerce su síntesis, cede al mismo tiempo a un potencial que reside en aquello que se le enfrenta y obedece sin conciencia a una idea de restitutio in integrum a partir de los fragmentos que él mismo produjo con sus golpes; ese elemento sin conciencia se torna consciente para la filosofía. Al pensar irreconciliable se le une la esperanza de reconciliación, ya que la resistencia del pensar ante lo que meramente es, es la violenta libertad del sujeto, también se refiere a aquello que fue sacrificado en el objeto a través de la constitución del objeto en objeto.

—Theodor W. Adorno, «Sobre la teoría de la experiencia intelectual (extractos)» (lección 11, fr. 13) en Lecciones sobre dialéctica negativa. Fragmentos de las lecciones de 1965/1966. Traducción de Miguel Vedda y edición en español bajo el cuidado de Mariana Dimópulos.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

2018 Books Read

Well, I read 202 books (approximately 46,376 pages ) in 2018. A short year. Here ’tis:

cover title author

The Boneyard, the Birth Manual, a Burial: Investigations Into the Heartland Madsen, Julia

The Teahouse Fire Avery, Ellis

All My Goodbyes Dimópulos, Mariana

Sad Laughter Ellis, Brian Alan *

Stealin…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

Fragmento de El parís del segundo imperio en Baudelaire, texto de Walter Benjamín, traducido por Mariana Dimópulos.

“Tout pour moi devient allégorie”.

Baudelaire , Le cygne

El genio de Baudelaire, que se nutre de la melancolía, es alegórico. Con Baudelaire, París se convierte por primera vez en objeto de la poesía lírica. Esta poesía no es arte regionalista, sino más bien la mirada del alegórico que se encuentra con la ciudad, la mirada del alienado. Es la mirada del fláneur, cuya forma de vida todavía baña la futura y desconsolada vida del hombre de la gran ciudad con una pátina de reconciliación. El fláneur está todavía en el umbral tanto de la gran ciudad como de la clase burguesa. Ninguna de las dos lo ha sometido aún. En ninguna de las dos está el fláneur en casa, sino que busca su asilo en la multitud. En Engels y Poe hallamos unas primeras contribuciones sobre la fisionomía de la multitud, que es el velo a través del cual la ciudad habitada se le aparece al fláneur como fantasmagoría. Allí, la ciudad es a veces paisaje, a veces habitación. Ambas cosas serán construidas por el centro comercial, que se aprovechará de la flánerie para la venta de mercancías. El centro comercial es la última comarca del fláneur.

En el fláneur, la inteligentsia se dirige al mercado. Según dice, para observarlo, pero en verdad lo hace para encontrar un comprador. En esta fase intermedia, en que todavía tiene mecenas pero ya comienza a familiarizarse con el mercado, aparece como bohéme. La indefinición de su posición económica corresponde a la indefinición de su función política, que se expresa de la forma más evidente en el caso de los conspiradores de profesión, quienes pertenecen en su totalidad a la bohéme. Su primer campo de trabajo es la armada, más tarde será la pequeña burguesía, a veces el proletariado. Pero esta clase ve a sus oponentes en los verdaderos líderes de este último. El manifiesto comunista representa el fin de su existencia política. La poesía de Baudelaire saca su fuerza del pathos rebelde de esta clase, pasándose al bando de los asociales. Su único intercambio sexual es con la prostituta.

“Facilis descensus Averno”.

Virgilio, Eneida

Lo extraordinario en la poesía de Baudelaire es que las imágenes de la mujer y de la muerte se entrelazan en una tercera, la de París. El París de sus poemas es una ciudad hundida, más bien bajo el mar que bajo la tierra. Los elementos crónicos de la ciudad -su formación topográfica, la vieja cuenca abandonada del Sena- encontraron en Baudelaire una impronta. Pero lo decisivo en el “idilio mortuorio” de la ciudad en Baudelaire es un sustrato social, moderno. Lo moderno es uno de los acentos principales de su poesía. Con el spleen parte en dos el ideal (“Spleen et idéal”). Pero es precisamente la modernidad la que cita la protohistoria. Esto ocurre a través de la ambigüedad propia de la situación social y del producto de esta época. La ambigüedad es la aparición en imagen de la dialéctica, la ley de la dialéctica detenida. Esta detención es utopía; de ahí que la imagen dialéctica sea imagen onírica. Una imagen semejante presenta la mercancía como tal: como fetiche. Una imagen semejante presentan los pasajes, que son tanto casa como calle. Una imagen semejante presenta la prostituta, que es vendedora y mercancía al mismo tiempo.

“Je voyage pour connaitre ma géographie”.

Aitfzeichnungen eines Irren. (Marcel Réja , L’art chez

Les fous, París, 1907, p. 131).

El último poema de Les fleurs du mal. “Le voyage”. “O Mort, vieux capitaine, il est temps! levons l’ancre!” . El último viaje del fláneur. la muerte. Su meta: lo nuevo. “Au fond de l’Inconnu pour trouver du Nouveau!”. Lo nuevo es una cualidad independiente del valor de uso de la mercancía. Es el origen de la apariencia, que es inalienable a las imágenes producidas por el inconsciente colectivo. Es la quintaesencia de la falsa conciencia, cuya agente incansable es la moda. Esta apariencia de lo nuevo se refleja, como un espejo en otro espejo, en la apariencia de lo siempre igual. El producto de esta reflexión es la fantasmagoría de la “historia de la cultura” donde la burguesía disfruta su falsa conciencia. El arte que empieza a dudar de su tarea y deja de ser “inséparable de l’utilité” (Baudelaire) debe hacer de lo nuevo su valor principal. El arbiter novarum rerum será para el arte el esnob, que es al arte lo que el dandi a la moda. Así como en el siglo xvn la alegoría se convierte en el canon de las imágenes dialécticas, en el siglo xix lo será la nouveauté. Junto a los magasins de nouveautés aparecen diarios. La prensa organiza el mercado de los valores espirituales, donde en un principio cotizan en alza. Los no conformistas se rebelan contra la entrega del arte al mercado, se agolpan alrededor del estandarte del “l’art pour l’art”. De este lema surge la concepción de la obra de arte total, que intenta inmunizar al arte frente al desarrollo de la técnica. La solemnidad con que se celebra a sí misma es la contraparte de la distracción que glorifica a la mercancía. Ambas se abstraen de la existencia social del hombre. Baudelaire sucumbe a la fascinación de Wagner.

--------------------------

Si te gustó este artículo, creemos que te pueden interesar alguno de estos:

La cultura de la traducción

Número 13: Género, arte, lucha

0 notes

Text

You Are in the Middle of Time: An Interview with Mariana Dimópulos

You Are in the Middle of Time: An Interview with Mariana Dimópulos

Mariana Dimópulos

Mariana Dimópulos’s novel All My Goodbyes, translated by Alice Whitmore, is a tale of murder in Patagonia and of wanderlust, or rather, a lust for an arrival that never quite happens. In crisp prose that is often as catchy as a pop song, the narrator jumps between Buenos Aires, Berlin, Heidelberg, and Málaga, and between maturity and youth, lovers and friends. The novel is…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

El libro de la semana: "La tarea del crítico", de Walter Benjamin

El libro de la semana: "La tarea del crítico", de Walter Benjamin

En su reciente “Carrusel Benjamin”, Mariana Dimópulos escribe: “Benjamin se propone por medio de la crítica el ejercicio de la contemporaneidad”. Pocos meses después de publicado ese libro inteligente, su autora presenta una antología anotada de textos benjaminianos, traducidos por Ariel Magnus, que permite leer a Benjamin en paz, deteniéndose solo en las verdaderas dificultades, no en la torpeza…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Walter Benjamin

1 note

·

View note