#marjorie garber

Text

Philip Sidney wrote a Defence of Poesie in 1595. Percy Shelley wrote a Defence of Poetry in 1821. Why, we might ask, does literature have to defend itself?

In part, it's Plato's fault. His famous exiling of poets from a well-ordered republic, on the grounds that they offered doxa, or opinion, rather than logos, or reason/discourse, instantiated an unhappy split between what we now call art and what we now call science. For Plato, the classic Greek poets—Homer and the tragic dramatists—whose work had formed the basis of a Greek education (paideia) depicted in their work all manner of deleterious behavior: murder, incest, cruelty, cowardice, treachery, strong passions out of control. Poetry thus weakened moral character and potentially influenced both actor/performer and audience. Since poetry in this period meant oral poetry, whether epic or dramatic—not the reading and study of written texts—the possibility of such emotional effects, rather than a rational assessment and distance, was, he thought, strong. If a schoolchild memorized Homer on the wrath of Achilles, what he learned was wrath, not poetry.

From the perspective of a modern educational system, where poetry is far less central than it was to the ancient Greeks, Plato's insistence on the dangers of poetry and poets may seem either quaint or excessive. But that is because we have so diminished the importance of literature (and music and art) over the years.

Both in Republic, where he describes what he regards as an ideal education for guardians and citizens of Athens, and elsewhere in his dialogues, Plato emphasizes the role of poetry and music on the one hand, and physical training on the other, as the key elements for training the soul and the body. In his own academy, Plato taught a different kind of learning, one based upon dialectics and philosophical reasoning, with the claim that literature should serve a moral and social function and should teach cultural elements like goodness, grace, reason, and respect for law.

This instrumental view of literature (Plato's poetry includes epic, tragedy, and other modes of imaginative writing), which demands that it do some good in the world, is, I will argue, part of the difficulty that literary study has wrestled with from its beginnings to the present. What is often called "the ancient quarrel between philosophy and poetry," the idea (voiced from the side of philosophy since Plato) that literature needs to make us better people, is now partnered with and augmented by a more modern set of questions about why we should read and study literature in a world increasingly global, economic, technological, and visual. Are the blandishments of the rhapsodes and interpreters and sophists, the orators, still dangerous? Still seductive? Does literature threaten society, or does it help to build society's values and institutions? Or are these the wrong questions and the wrong justifications for literature and its readers?

Marjorie Garber, The Use and Abuse of Literature

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Yet in the opening scenes we see in Lady Macbeth none of this frailty. We see instead rigidity, resolution, and the rejection of a restricted notion of a woman’s place. Lady Macbeth is the strongest character in the play. From the first moment we see her she is resolute, apparently without moral reservation, and devastatingly scornful of her husband’s inner struggles, which she equates with unmanliness. The opposite of ‘man’ in this case can be either ‘child’ or ‘woman.’ . . . . In fact, as she repeatedly makes clear, she sees herself as the stronger, the dominant, the more conventionally ‘masculine’ of the two. I think we can say with justice that those unisex witches, with their woman’s forms and their confusingly masculine beards, are, among other things, dream images, metaphors, for Lady Macbeth herself: physically a woman but, as she claims, mentally and spiritually a man. It’s well to remember at points like these that the actor playing Lady Macbeth, like the actor playing the far more ‘feminine’ Lady Macduff, would have been male. Gender on the early modern public stage was performed rather than ‘natural.’ Like darkness, which sometimes needed to be invoked by language–or props, such as onstage candles and lanterns–in the middle of an outdoor afternoon performance, gender difference, femaleness, was an achieved effect rather than a mirror of reality. And this is very germane to the question of Macbeth’s manliness, which his wife so regularly challenges. Neither manliness nor womanliness can be taken for granted in a world, and on a stage, where gender is by definition an act.”

-Marjorie Garber, Shakespeare After All (2004)

0 notes

Photo

Bad movie I have Mary Poppins 1964

#Mary Poppins#walt disney#Julie Andrews#Dick Van Dyke#David Tomlinson#Glynis Johns#Hermione Baddeley#Reta Shaw#Karen Dotrice#Matthew Garber#Elsa Lanchester#Arthur Treacher#Reginald Owen#Ed Wynn#Jane Darwell#Arthur Malet#James Logan#Don Barclay#Alma Lawton#Marjorie Eaton#Marjorie Bennett#Walter Bacon#Frank Baker#Robert Banas#Philo Barnhart#Rudy Bowman#Marc Breaux#Art Bucaro#Daws Butler#Roy Butler

1 note

·

View note

Text

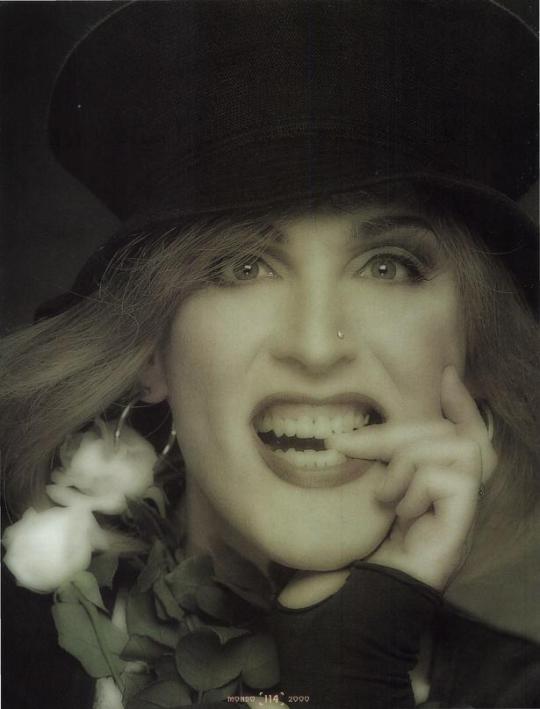

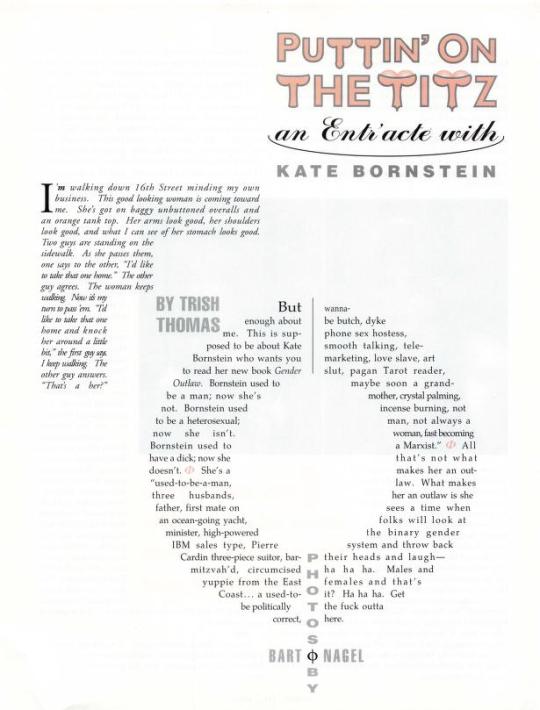

Interview with nonbinary trans author Kate Bornstein, promoting her book Gender Outlaw (Mondo 2000 #13, 1995)

Full text under cut

I‘m walking down 16th Street minding my own business. This good looking woman is coming toward me. She's got on baggy unbuttoned overalls and an orange tank top. Her arms look good, her shoulders look good, and what I can see of her stomach looks good. Two guys are standing on the sidewalk. As she passes them, one says to the other, “I'd like to take that one home.” The other guy agrees. The woman keeps walking. Now it's my turn to pass 'em. “I'd like to take that one home and knock A her around a little bit,” the first guy says. I keep walking. The other guy answers. “That's a her?”

But enough about me. This is supposed to be about Kate Bornstein who wants you to read her new book Gender Outlaw. Bornstein used to be a man; now she’s not. Bornstein used to be a heterosexual; now she isn't. Bornstein used to have a dick; now she doesn’t.

She’s a “used-to-be-a-man, three husbands, father, first mate on an ocean-going yacht, minister, high-powered IBM sales type, Pierre Cardin three-piece suitor, bar-mitzvah’d, circumcised yuppie from the East Coast… a used-to-be politically correct, wanna-be butch, dyke phone sex hostess, smooth talking, telemarketing, love slave, art slut, pagan Tarot reader, maybe soon a grandmother, crystal palming, incense burning, not man, not always a woman, fast becoming a Marxist.”

All that’s not what makes her an outlaw. What makes her an outlaw is she sees a time when folks will look at the binary gender system and throw back their heads and laugh— ha ha ha. Males and females and that’s it? Ha ha ha. Get the fuck outta here.

Bornstein’s looking forward to us all living in what author Marjorie Garber (Vested Interests, Routledge) calls the Third Space. “This whole concept of three is so beautiful,” Kate says, “because it includes the first two. I don’t say there’s a third space that exists between men and women. I say there’s a third space outside of the Binary which leaves the Binary as this construct off to the side, very fragile and apt to fall apart.”

If I were a man, everything about me that brings me grief in the world—the way | walk, the way I talk, the way I think, the way | stand, the way I sit, the way I dress, the way | cut my hair, how much I weigh, how much weight I lift—would not only be acceptable, it would be revered. If we lived in the Third Space, it wouldn't even matter.

Bornstein had to learn a lot of rules in order to fit in. Like when a man walks down the street he looks people in the eye; when a woman walks down the street she looks at the ground. And women talk different. They have higher, breathier voices and their speech is more modulated. In mixed conversations, it’s the woman's job to laugh at the bad jokes and fill in the awkward silences. They smile constantly while they’re talking and use tag questions to qualify sentences, like “you know what I mean?”

“All of these customs are forms of self-deprecation,” says Bornstein, “like learning how to keep my knees together and not putting my arm across the back of my seat in the subway train. A lot of that was not so much to be a woman as to pass as a woman, so that I wouldn't call attention to myself.”

If we lived in the Third Space, she wouldn't have had to worry. In fact, if we lived in the Third Space, she might not even have had penile conversion surgery.

“I don’t do well with might-have-beens,” she says. “I resent that I was manipulated into that surgery by every signpost in the culture. I was not aware of other possibilities at the time. I was a total subscriber to the Binary and to the genitals by which it stands.

“I knew I wasn’t BOY, I knew I wasn’t MAN. Neither of those categories fit for me. It didn’t feel right, I have no idea why. I tried for thirty some odd years and it didn’t work. The only other option I saw in the culture was GIRL, or WOMAN. Nowhere did I see that it was okay to be a “real woman”—which I believed in—with a penis! So the next step was get rid of the penis. This insistence on the Binary and the genital imperative that signals the Binary coerced me into that. If I knew everything that I know now, would I do it again? Yes. Absolutely yes, because sex is so much more fun now.”

Back to this idea of the Third Space, how do we get there?

“Cyberspace would be a doorway into the Third Space,” according to Bornstein. “Cyberspace frees us up from the restrictions placed on identity by our bodies. It allows us to explore more kinds of relationships.

“I can go online as anything. I go online as various kinds of women. I've gone online as a guy a couple of times; I’m playing a stable boy in a vampire scenario now. I’ve gone online as different monsters. I’ve gone online as Mr. Spock in a ‘Star Trek’ scenario.

“Cross-gender identity surfing online is so telling: Men slum and women step into the trappings of power as men. You talk to a man after he’s been a woman online and he'll usually laugh and describe some kind of sex he had, usually lesbian sex. But you talk to a woman who's been surfing as a man, there’s this spark there. There’s this wonder. There's this—'They really do have this power!’ As soon as men cop to the idea that women are learning this, they’re gonna be more frightened.”

Bingo.

In Gender Outlaw, Bornstein asks: “If wealth and power are important, and if in this world wealth and power belong to men, then why did I cease being a man and give up that wealth and power?"

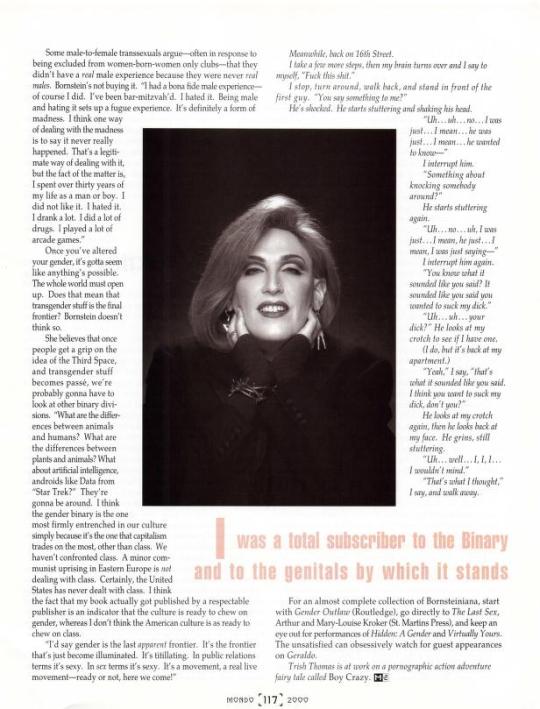

Some male-to-female transsexuals argue—often in response to being excluded from women-born-women only clubs—that they didn’t have a real male experience because they were never real males. Bornstein’s not buying it. “I had a bona fide male experience—of course I did. I’ve been bar-mitzvah’d. I hated it. Being male and hating it sets up a fugue experience. It’s definitely a form of madness. | think one way of dealing with the madness is to say it never really happened. That’s a legitimate way of dealing with it, but the fact of the matter is, I spent over thirty years of my life as a man or boy. I did not like it. I hated it. I drank a lot. I did a lot of drugs. I played a lot of arcade games.”

Once you've altered your gender, it’s gotta seem like anything’s possible. The whole world must open up. Does that mean that transgender stuff is the final frontier? Bornstein doesn’t think so.

She believes that once people get a grip on the idea of the Third Space, and transgender stuff becomes passé, we're probably gonna have to look at other binary divisions. “What are the differences between animals and humans? What are the differences between plants and animals? What about artificial intelligence, androids like Data from “Star Trek?” They're gonna be around. | think the gender binary is the one most firmly entrenched in our culture simply because it’s the one that capitalism trades on the most, other than class. We haven't confronted class. A minor communist uprising in Eastern Europe is not dealing with class. Certainly, the United States has never dealt with class. I think the fact that my book actually got published by a respectable publisher is an indicator that the culture is ready to chew on gender, whereas I don’t think the American culture is as ready to chew on class.

“I'd say gender is the last apparent frontier. It’s the frontier that’s just become illuminated. It’s titillating. In public relations terms it’s sexy. In sex terms it’s sexy. It’s a movement, a real live movement—ready or not, here we come!”

Meanwhile, back on 16th Street.

I take a few more steps, then my brain turns over and I say to myself, “Fuck this shit.”

I stop, turn around, walk back, and stand in front of the first guy. “You say something to me?”

He’s shocked. He starts stuttering and shaking his head.

“Uh…uh…no…I was just…I mean…he was just…I mean…he wanted to know—"

I interrupt him.

“Something about knocking somebody around?”

He starts stuttering again.

“Uh…no…uh, I was just… I mean, he just… I mean, I was just saying—"

I interrupt him again.

“You know what it sounded like you said? It sounded like you said you wanted to suck my dick.”

“Uh…uh… your dick?” He looks at my crotch to see if I have one.

(I do, but it’s back at my apartment.)

“Yeah,” I say, “that’s what it sounded like you said. I think you want to suck my dick, don't you?”

He looks at my crotch again, then he looks back at my face. He grins, still stuttering.

Uh...well...I, I, I... I wouldn't mind.”

“That's what I thought,” I say, and walk away.

For an almost complete collection of Bornsteiniana, start with Gender Outlaw (Routledge), go directly to The Last Sex, Arthur and Mary-Louise Kroker (St. Martins Press), and keep an eye out for performances of Hidden: A Gender and Virtually Yours. The unsatisfied can obsessively watch for guest appearances on Geraldo.

#was looking at old cyberpunk magazines and this one just happened to have an interview with bornstein in it what a treat 😊#warning for some dated editorializing as you can imagine but its still cool to see where gender politics were three decades ago#kate bornstein#gender outlaw#mondo 2000#///

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi i have been obsessed with your “the monster’s body is a cultural body etc” post since i saw it like a month ago. do you have any book recs where i can read more about this, like, forever. (I’m aware of your podcast I’m checking it out too) <3

i'm glad you liked it, it's an honor to introduce the people of tumblr to cohen's seven theses

first and foremost i would recommend The Monster Theory Reader, ed. Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock, which includes several seminal essays including:

"The Uncanny" by Sigmund Freud

"The Uncanny Valley" by Masahiro Mori

"Approaching Abjection" by Julia Kristeva

"Horror and the Monstrous-Feminine: An Imaginary Abjection" by Barbara Creed

"The Monster and the Homosexual" by Harry M. Benshoff

i would also recommend the book in which Cohen first published his seven theses, Monster Theory: Reading Culture, ed. Jeffrey Jerome Cohen

(i must admit that i haven't gotten around to reading either of these books in full yet)

aside from the essays mentioned above, here are some foundational texts for monster theory but not specifically about monster theory:

The Uses of Enchantment by Bruno Bettelheim

Mythography: The Study of Myths and Rituals by William Doty

Vested Interests: Cross-Dressing and Cultural Anxiety by Marjorie Garber

monster theory/horror criticism texts i've read:

Monsters in the Closet by Harry M. Benshoff

Skin Shows by Jack Halberstam

Murder Most Queer by Jordan Schildcrout

It Came from the Closet, ed. Joe Vallese

Horror by Brigid Cherry

Men, Women, and Chain Saws by Carol Clover

Dark Places by Barry Curtis

The Dread of Difference, ed. Barry Keith Grant

The Monster Show by David J. Skal (SEE NOTE BELOW)

Darkly: Black History and America's Gothic Soul by Leila Taylor

The Ghost: A Cultural History by Susan Owens

and some others i own but haven't read yet:

Dark Carnivals by W. Scott Poole

Phantom Past, Indigenous Presence: Native Ghosts in North American Culture and History by Colleen E. Boyd and Coll Thrush

Queer for Fear: Horror Film and the Queer Spectator by Heather O. Petrocelli

Pretend We're Dead: Capitalist Monsters in American Pop Culture by Annalee Newitz (just started this, already love it)

Theatre and the Macabre, ed. Meredith Conti and Kevin J. Wetmore, Jr.

and i can't neglect to mention The Monster in Theatre History: This Thing of Darkness by Michael Chemers

before i say anything further i want to give one warning. my particular interest is on monstrosity and queerness (probably evident based on some of my recommendations). monster theory and horror criticism have generally been rooted in psychoanalytic theory, particularly as it has been interpreted through a feminist lens. unfortunately, this leads to a lot of arguments and interpretations that are sex essentialist and fail to address gender with the necessary nuance. this is particularly true in Men, Women, and Chain Saws and The Dread of Difference.

(Vested Interests is… complicated. it's not monster theory exactly but cohen cites it. garber is generally better than the others mentioned here in her consideration of trans people but her work can still be uncomfortable.)

i have a lot of reservations about recommending The Monster Show. i loved reading it and i think skal has great analysis. somehow, however, in the middle of his discussion of how marginalized people have been historically monsterized in american culture, he has the audacity to cite The Transsexual Empire by Janice Raymond, the ur-text of TERF ideology, and skal uses this text to monsterize trans women. it's disgusting and reprehensible, and if the rest of the book wasn't so strong i wouldn't recommend it

the best medicine i have are texts by trans people. It Came from the Closet is an anthology with several essays by trans people, i adore it. i am forever obsessed with Gender Outlaw by Kate Bornstein, which isn't exactly monster theory, but i would say it's monster theory adjacent and i wish everyone would read it

and if you haven't, you must read "My Words to Victor Frankenstein Above the Village of Chamounix: Performing Transgender Rage" by Susan Stryker. (see i even put a link to that one. drop everything and read it now)

alright if you're still with me i have a couple other things to put out there:

the docuseries Queer for Fear, available on Shudder, is incredible and i'm obsessed with it

she seems to be inactive these days but @draculasdaughter has a lot of posts quoting texts and articles on monster theory/horror criticism that i highly recommend

i've only seen the jacob geller videos on this list but i mean to watch this youtube playlist of video essays about horror, fear, and dread

and i also keep a #monster theory tag on my blog that has various posts on the subject, some funny and some earnest

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every time I publish a fic I think "wow, I'll have so much more time to work on my other fics!" only to learn that it is hard to get right back in the saddle in the emotional aftermath of finishing a story. So I have been taking a self-imposed break from fic writing these past few days and have determinedly been doing thesis work and reading more of this massive Marjorie Garber book on bisexuality and watching films and - most importantly - just fucking around on the internet. I think this is good for my creative process.

#as well as 'vigorously outlining my next meta post in the wee hours of the morning'#(as i did last night)#the zest for nbc hannibal has absolutely not abated#justalphathings

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

people I'd like to get to know better ✨

tagged by @jules-in-deep <3

last song: austin by dasha

currently watching: old marjorie garber lectures my beloved

spicy/savory/sweet: sweet sweet sweet sweet

relationship status: i seem to have stumbled my way into a throuple by mistake. kinda works though.

current obsession: steinbeck's retellings of arthurian myths

fave color: NECTAR YELLOW

tagging: dougiejack im only tagging u. ur the only name i can think of atm. kinda romantic if u think about it. @crent-trimm

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books, 2022

Favorite books, first-time reads:

Ada Palmer, Perhaps the Stars (Terra Ignota #4)

J. Anderson Coats, Spindle and Dagger

Gayle Brandeis, Many Restless Concerns: The Victims of Countess Bathory Speak in Chorus

Vanessa Springora, Consent: A Memoir

Shola von Reinhold, LOTE

James Gilligan, Violence: Reflections on a National Epidemic

Marjorie Garber, Shakespeare After All

Runners up:

Marcial Gala, Call Me Cassandra; Faith Jones, Sex Cult Nun; Maurice Chammah, Let the Lord Sort Them: The Rise and Fall of the Death Penalty; Inua Ellams, The Half-God of Rainfall; Reginald Dwayne Betts, A Question of Freedom and Felon; Roland Barthes, Image - Music - Text; Robert A. Schanke, That Furious Lesbian: The Story of Mercedes de Acosta, Colston Whitehead, Harlem Shuffle

Notable re-read experiences:

Megan Whalen Turner, The Queen's Thief series

Tanith Lee, Lords of the Flat Earth 1-3

Anne Rice, The Witching Hour

Adele Géras, Troy

Hanya Yanagihara, A Little Life

the latter half of the Shakespeare canon

Books that made me the angriest:

Natalie Haynes, A Thousand Ships

Rachel Hope Cleves, Unspeakable: A Life Beyond Sexual Morality

Genevieve Gornichec, The Witch's Heart

Hannah Capin, Foul is Fair

Total books as of 12/30 is roughly 341 (that includes some but not all of the rereads). I of course had many other notable reading experiences that do not fit into any of the above categories, including Dion Fortune's The Sea Priestess and the 13 Sookie Stackhouse books.

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey Marley, it'd be cool if you would drop a list of the masculinity in film books you're reading. No pressure tho!

Oh yeah for sure, lol sorry I have a tendency to default to vagueness when I'm talking about anything outside of fandom.

There's a lot, I went on a spree for a few weeks lol, so this is under a cut

Only one I've read cover to cover so far is Armed Forces: Masculinity and Sexuality in the American War Film - Robert Eberwein which was both interesting and frustrating in that a lot of it was (mildly defensively lol, as a response to a lot of queer film theory) explaining how a lot of homoerotic shit isn't intended to be interpreted as actually gay, but I'm glad I read it because I was specifically trying to understand how contemporary audiences viewed homoerotic shit.

Books I've read at least a chapter of:

Men, Masculinity, and the Media - Steve Craig

Running Scared: Masculinity and the Representation of the Male Body - Peter Lehman

Masculinity: Bodies, Movies, Culture - Peter Lehman

Masculinity and Popular Television - Rebecca Feasey

Buffoon Men: Classic Hollywood Comedians and Queered Masculinity - Scott Balcerzak

Shadows of Doubt: Negotiations of Masculinity in American Genre Films - Barry Keith Grant

Screening the Male: Exploring Masculinities in Hollywood Cinema - Steven Cohan

Laughing Matters: Understanding Film, Television, and Radio Comedy - John Mundy, Glyn White

Laughing Hysterically: American Screen Comedy of the 1950s - Ed Sikov (highly recommend just for the essay on Some Like It Hot)

What Made Pistachio Nuts?: Early Sound Comedy and the Vaudeville Aesthetic - Henry Jenkins

also shoutout to this article

Books I've obtained but haven't looked through yet:

American Cinema of the 1970s: Themes and Variations - Lester D. Friedman

Hollywood Androgyny - Rebecca Bell-Metereau

The New Hollywood: What the Movies Did With the New Freedom of the Seventies - James Bernardoni

Manhood in Hollywood: From Bush to Bush - David Greven

Girls Will Be Boys: Crossdressed Women, Lesbians, and American Cinema - Laura Horak

Hard Bodies: Hollywood Masculinity in the Regan Era - Susan Jeffords

The Remasculinization of America: Gender and the Vietnam War - Susan Jeffords (I've actually read the first Jeffords in uni and parts of the second but they're pretty psychoanalytical so ymmv)

Deviant Eyes, Deviant Bodies: Sexual Re-orientations in Film and Video - Chris Straayer

Masculinity in Fiction and Film: Representing Men in Popular Cultures 1945-2000 - Brian Baker

Masculinity in the Contemporary Romantic Comedy - John Alberti

Out in Culture: Gay, Lesbian and Queer Essays on Popular Culture - Corey K. Creekmur, Alexander Doty

Flaming Classics: Queering the Film Canon - Alexander Doty

Making Things Perfectly Queer: Interpreting Mass Culture - Alexander Doty

Vested Interests: Crossdressing and Cultual Anxiety - Marjorie Garber

Queer Images: A History of Gay and Lesbian Film in America - Harry M. Benshoff

Ghost Faces: Hollywood and Post-Millennial Masculinity - David Greven

Ethereal Queer: Television, Historicity, Desire - Amy Villarejo

Gender Terrains in African Cinema - Dominica Dipio

Masculinity and Monstrosity in Contemporary Hollywood Films - Kirk Combe and Brenda Boyle

Open Secret: Gay Hollywood 1928-1998 - David Ehrenstein

Screened Out: Playing Gay in Hollywood From Edison to Stonewall - Richard Barrios

Hollywood from Vietnam to Regan - Robin Wood

In a Lonely Street: Film Noir, Genre, Masculinity - Frank Krutnik

Unamerican Hollywood: Politics and Film in the Blacklist Era - Frank Krutnik and others

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

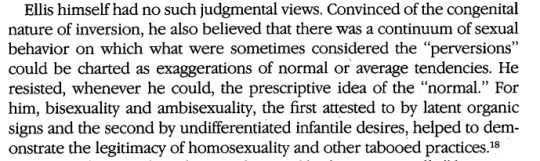

twentieth century views on bisexuality and the ‘sexual invert’, from “Ellis In Wonderland” by Marjorie Garber

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

ADVICE NEEDED!!

what comic book should i start next?

bprd hell on earth vol 4

bone vol 1

what nonfiction book should i start next?

the war that killed achilles by caroline alexander

plainwater by anne carson

shakespeare and modern culture by marjorie garber

#the last one is DEFINITELY the one i've had the longest bc kaitlin gave it to me probably at least 6 years ago#captain's reading log

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The play–any play, but especially a strong one–is the sum of all its meanings, all its intentions, conscious and unconscious, including some that the author could never have intended. We might say that this is above all what makes a work of literature worth studying. Certainly it is one of the things that make it great.

— Marjorie Garber, Shakespeare After All

0 notes

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

i've done a decent amount of reading of queer horror theory and feminist horror theory, and though this is the exact intersection of several of my research interests it is also particularly aggravating

i'm currently reading a book from 1991 called vested interests: cross-dressing and cultural anxiety (by marjorie garber) as research for a paper i'm writing and i was really impressed because at one point the author puts into words a problem i have with so much of the horror criticism i've read:

The appeal of cross-dressing is clearly related to its status as a sign of the constructedness of gender categories. But the tendency on the part of many critics has been to look through rather than at the cross-dresser, to turn away from a close encounter with the transvestite, and to want instead to subsume that figure within one of the two traditional genders. To elide and erase—or to appropriate the transvestite for particular political and critical aims.

it's hard to explain how elated i was to read that; since this is such a niche field and i'm an independent researcher at the moment i don't have anyone to air my grievances to who's familiar with the discourse i've become enmeshed in, and garber described just exactly what i see all the time

academics in this field repeatedly "look through" the way horror unsettles gender. in all fairness, most of the seminal essays and books on the topic were published by cis people before the new millennium, so i'm ready to accept a certain amount of ignorance to queer issues, and especially trans issues. but i have seen academics writing about norman bates and buffalo bill, dressed to kill and sleepaway camp—horror films that explicitly engage with the trope of the cross-dressed killer, three of which engage with the idea of transness explicitly (and problematically)—and they can only read these characters and plots as allegorical and as psychological models instead of considering for a moment that transgender people are not… metaphors

(a secondary problem but in addition to failing to consider real trans people these academics regularly fail to consider the existence of a queer subject; the moviegoer and psychological subject is only ever constructed as heterosexual, so same-gender desire is also read as an allegory instead of literal—looked through instead of looked at)

(i'd also be remiss not to mention the monster show by david j. skal, an incredible book about the relationship between horror and pop culture that regularly discusses how horror preys on fears of minorities… until he starts to quote the transsexual empire… uncritically)

anyway, i'm reading vested interests and initially i'm so impressed. and i'm trying to be gracious and flexible because it was published in 1991. but whenever she moves away from strict cross-dressers (shakespearean characters and actors, tootsie, yentl) to discussions of actual trans people (including billy tipton and renée richards) she goes back and forth with pronouns and whether she considers the person a man or a woman or a third thing and whether she's affirming their gender or not and it's just like. oh god honey please stop

(lastly i'd just like to add that i only even found out about this book bc kate bornstein quoted it in their book gender outlaw and so if a nonbinary trans lesbian can stomach this book so can i)

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Another Victorian critic, E.P. Vining, suggested that the answer to the problem was that Hamlet was really a woman in disguise, and that this accounted for both 'his' reluctance to fight and 'his' famous delay. Vining was writing at a time when a good deal of scholarship on gender ambiguity and erotic types was being written, and being read, by such influential figures as Havelock Ellis and Edward Carpenter. In fact, part of what made Vining believe that the 'mystery' of Hamlet was his/her gender was precisely the fact that Shakespeare's character seemed to behave in ways that some observers in the late nineteenth century regarded as unmanly. 'The question may be asked,' he wrote, 'whether Shakespeare, having been compelled by the course and exigencies of the drama to gradually modify his original hero into a man with more and more of the feminine element, may not at last have had the thought dawn upon him that this womanly man might be in very deed a woman . . . ?' Vining's speculations were influential in the production of a 1920 German silent film version of Hamlet, starring the Danish actress Asta Nielsen. In the film, the Danish throne can be occupied only by a male heir, so the female Hamlet is brought up as a man in order to provide political continuity and avoid the loss of Danish lands to arch-foe Norway. The resulting script produced some highly eroticized scenes with a Horatio who does not know Hamlet's secret, and a deathbed revelation of her true gender. The part of Hamlet has not infrequently been played by actresses, including Sarah Bernhardt in 1899 and, more recently, Diane Venora in 2000. 'I cannot see Hamlet as a man,' Bernhardt declared, when asked about her characterization. 'The things he says, his impulses, his actions entirely indicate to me that he was a woman.'

"In Shakespeare’s own time, not only the Player Queen but also the 'real' queen, Gertrude, and Ophelia, too, would have been played by boys, so that these nineteenth and twentieth-century dislocations in the other direction are not, perhaps, so out of keeping."

- Marjorie Garber, from the Hamlet chapter in Shakespeare After All (2004)

#i don't really have anything to add or to extrapolate from this i just thought it was an interesting passage#shakespeare#marjorie garber#hamlet#books

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

– Character: The History of a Cultural Obsession by Marjorie Garber

25 notes

·

View notes