#mizuya shrine

Text

'24.1.21 二月堂付近、手向山八幡宮、水谷神社、春日大社境内、中の禰宜道にて

少し前の雨降りの日。カメラにタオル被せて軒下伝いに移動しつつ撮り歩き。

明後日の日曜は雪予報・・ほんとに降るのかなぁ・・。

#奈良#nara#奈良公園#nara park#日本#japan#東大寺#todaiji temple#手向山八幡宮#tamukeyana hachimangu shrine#水谷神社#mizuya shrine#春日大社#kasuga tasiha shrine#中の禰宜道#nakano negimichi path#冬#winter#雨#rainy day#photographers on tumblr#natgeoyourshot

311 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 7 (63): Rikyū’s Ji-butsu-dō [持佛堂].

63) Concerning [Ri]kyū’s ji-butsu-dō [持佛堂], to the east of the katte [勝手] attached to his two-mat tearoom, another two-mat room was [erected]¹. This [two-mat room] was surrounded, on three sides, by roofed verandas; and in the toko at the head of the room, [the image of his] “personal Buddha” was [installed]².

On the memorial days, when [Rikyū’s] thoughts turned to [his ancestors] and he performed a memorial service, invariably oshō [和尚], accompanied by this monk, were always invited to attend³. Inside the ji-butsu[-dō] the small utensils [= the chaire and temmoku-chawan] were of an even number; and these [utensils] were displayed on yin-kane. (If [you] asked [him] why [it was only the small utensils that were arranged on yin-kane], [Rikyū] would have replied that more than this was unnecessary [to cause the arrangement to be yin, as was appropriate when offering tea in memory of the departed]⁴.)

On one occasion, on the day of Sen’ami’s memorial service, [Rikyū] prepared tea using [his] small nasubi [chaire]: the chaire was displayed as an yin hitotsu-mono [一物]⁵.

_________________________

◎ According to Tanaka Senshō’s commentary, the description given here resembles the several Sen families’ Rikyū-dō [利休堂]* -- their memorial shrines to Rikyū as the ancestor of their families. As the language of this entry is likewise of the second half of the seventeenth century, this was probably another instance where an attempt was being made to validate these constructions by making it seem that Rikyū had used a similar sort of shrine to venerate his ancestors. This is also one of the few actual documents where the mysterious Sen’ami [千阿彌]† is named as the ancestor of the family.

Tanaka laments the fact that no drawing has come down to us to inform us of the room’s actual appearance -- as would have been expected given the rather vague description provided by the text.

It is important to point out that the Tokugawa bakufu wished to encourage the worship of the ancestors -- particularly those individuals who had been instrumental in their rise to power -- so it is probably in this vein that this entry was added to the collection.

___________

*The description given in this entry makes it difficult to associate this construction with any of Rikyū’s known residences. Since Rikyū always had the guests’ entrance on the north side of the tearoom, in a room where the guests’ entrance was in the same wall adjoined by the mukō-ro (the 2-mat rooms with a geza-toko [下座床]), this would place the ji-butsu-dō next to the wall behind the guests’ seats (which would impede the light entering through the important windows behind their backs); if it is referring to the Mozuno ko-yashiki (as most documents from the Edo period that can be clearly sited do), this would place the ji-butsu-dō beside the tearoom’s mizuya-veranda. Now while that is not inherently impractical -- especially since it seems that the ji-butsu-dō did not have its own attached katte -- it would obstruct the light entering the room from that side (the Mozuno ko-yashiki had a shōji panel as the door of the dōko, the intention of which was to allow light to enter at floor level; and if a building was constructed next to the mizuya), at least unless there was so much space between the two that the mizuya would not really provide any support to the ji-butsu-dō.

The fact that there was no katte, however, makes this room appear similar to the Mozuno ko-yashiki, however, because in that room, too, the host entered from the veranda (on which the guests sat during the naka-dachi).

The modern versions of the Rikyū-dō (usually referred to as sō-dō [祖堂], ancestor shrines) present in the several Sen family compounds have been rebuilt several times since the seventeenth century, and so their present iterations may not reflect their original shapes or configurations (indeed, they all seem to have been reimagined as places where a larger number of people could be seated, most of whom would be spectators to the act of offering of tea).

†This name indicates that he was an adherent to the Amidist sect from which chanoyu itself sprang; and he is purported to have been a member of the dōbō-shū [同朋衆] (though his name does not seem to be mentioned in this, or any other, capacity in any of the accounts from the Ashikaga period). Still, while he may not have served in Japan, as that system of high ranking governmental advisers providing a sort of cultural education to the ruler imitated the hwa-rang-do [화랑도 = 花郎道 or 花郎徒] of the Goryeo dynasty, it is possible that this person served in such a capacity in the court there, and that his memory was brought back from the continent by Rikyū, who chose to recognize him as the familial patriarch by taking the surname Sen [千] (which is a Korean family name, rather than a Japanese surname) as his own when he returned to Japan.

¹Kyū no ji-butsu-dō ha, ni-jō-shiki no cha-seki no katte yori, higashi no kata ni mata ni-jō-shiki ni shite [休ノ持佛堂ハ、二疊鋪ノ茶席ノ勝手ヨリ、東ノ方ニ又二疊敷ニシテ].

Ji-butsu-dō [持佛堂] is a dedicated room (often constructed as a separate building attached to the residence by a hallway or veranda) in a private residence in which a statue of the household’s “personal Buddha,” and the memorial tablets of their deceased members, are kept. It functions as a private oratory; and it is there that offerings to the ancestors (such as during New Year’s, and the O-bon festival) are made.

Ni-jō-shiki no cha-seki no katte yori, higashi no kata ni mata ni-jō-shiki ni shite [二疊敷の茶席の勝手より、東の方に又二疊敷にして] means “from the katte of the 2-mat tearoom, on the east side there was another 2-mat room.”

This 2-mat room would have been the ji-butsu-dō [持佛堂].

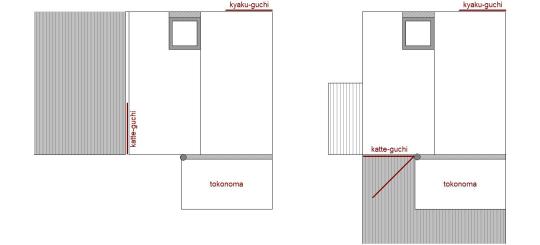

Since Rikyū preferred to have the guests’ entrance on the north side of the tearoom, and since his earlier 2-mat rooms were configured with a geza-toko [下座床]*, with the mukō-ro cut near the guests’ entrance, this means that the katte would have had to be either on the south or west side of the room, as shown below.

Because the tearoom itself is to the east of the katte in Rikyū’s earlier rooms (on the left), this text could not be referring to this kind of room.

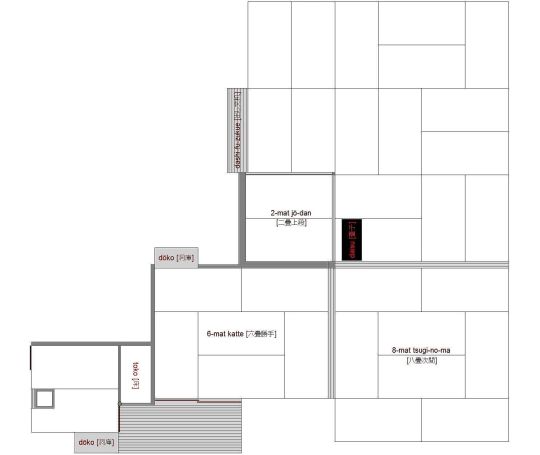

In the case of the room shown on the right, which was the sort of 2-mat room (with a hinged katte-guchi, that imitated that door originally proposed for the 1.5-mat room) that was erected in Rikyū’s residence in Kyōto, the problem is that to the east of the 6-mat katte was Rikyū’s 18-mat reception room (with 2-mat jō-dan) -- according to surviving records of this room on which the below sketch is based†. While some versions of this drawing show a single shōji in the wall perpendicular to the dōko in the katte (though with no mention of what lay beyond that door), if the veranda that surrounded the ji-butsu-dō on three sides adjoined the katte there, the ji-butsu-dō would be east of the 2-mat room, not its katte -- and such a construction would probably impact the lighting within the tearoom itself‡.

As for the Mozuno ko-yashiki, Rikyū’s final 2-mat room, it had a mizuya-dōko [水屋洞庫], and so did not have a katte at all.

In light of these details, it is difficult to understand the logistics from this description.

__________

*A geza-toko [下座床], which had been Rikyū's preferred orientation for the toko in his small rooms since the creation of his 2-mat daime Jissō-an [實相庵] in 1555, is a toko located on the guests’ left, and so at the foot of the room (if the location of the mukō-ro is the upper side).

The 1.5-mat room (which was created not long after the 2-mat daime room) also featured a geza-toko -- though he quickly abandoned it since it was too difficult for the guests to use).

The geza-toko arrangement, regardless of the size of the room, allows the host to face the shōkyaku simply by turning toward his right. This enables him to offer the bowl of tea directly to that guest -- which may have been a large part of the reason for his favoring that orientation.

†It seems that Rikyū preferred to connect his 2-mat rooms to the main building, while it was the 4.5-mat room that was detached. The reason appears to have been because this allowed the guests to be served the kaiseki in the 6-mat katte; and at the conclusion of the gathering they would be able to walk directly into the shoin (which would have been an important detail when serving people such as Hideyoshi).

‡Several different representations of Rikyū’s residence within Hideyoshi’s Jurakudai [聚樂第] compound have come down to us. The above floor-plan is based on the only one that shows how the 2-mat room was connected to its katte, and, ultimately, to the 18-mat “colored shoin” -- though none of the drawings indicate the presence of a ji-butsu-dō anywhere on the grounds (admittedly, they only focus on showing the arrangement of the main buildings within the compound).

In one version of this sketch that is held by the Sen family (and on which Omotesenke’s reconstruction of the “colored shoin” is said to have been based), any reference to the 2-mat room is completely missing (and a notation on that document indicates that, rather than the pair of shōji that lead to the 2-mat room, a kuguri [クヽリ] -- presumably a nijiri-guchi or other low entrance of that sort -- was found in that place). While many of the other details of the six-mat room are the same, it is not named as a katte (probably since, without the tearoom, there is no other room to which it could serve as this appendage).

²San-bō ni hisashi wo mawashi, shōmen ni toko, ji-butsu ari-shi nari [三方ニヒサシヲマハシ、正面ニ床、持佛アリシ也].

San-bō ni hisashi wo mawashi [三方に庇を廻し]: hisashi [庇] means either an aisle room (a narrow room that encircles one or more sides of the main room, which allows servants and functionaries to move around without disturbing the people seated within the main room), with the outer sides facing the gardens -- with or without shōji or latticed shutters (shitomi-do [蔀戸]) to protect the interior from the weather, or its occupants from being spied upon); or, as here, a simple veranda protected by an overhanging roof (sometimes with a low balustrade standing at the outer edge).

San-bō ni [三方に] means that the hisashi were found on three sides of the central room*.

Shōmen ni toko [正面に床]: shōmen ni [正面に]† means directly, head-on -- that is, the toko was located at the deepest part of the room -- so the room was oriented like the Mozuno ko-yashiki, with the recess at the far end of the room. The hisashi (likely separated from the interior of this 2-mat room by three banks of shōji) surrounded the room on the other three sides. This is the arrangement shown below (the dimensions of the three hisashi are, of course, pure speculation).

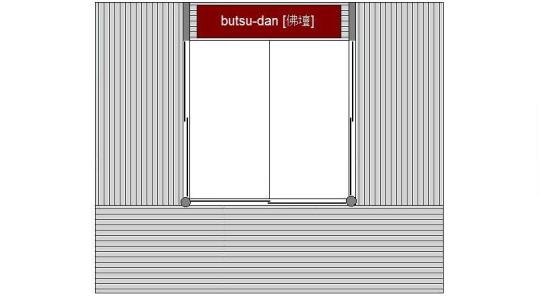

Ji-butsu ari-shi nari [正面に床、持佛ありしなり]: ji-butsu [持佛] means a personal image of the Buddha, one’s own Buddha statue. In other words, an image of the Buddha‡ was installed in the toko (probably resting on some sort of butsu-dan [佛壇], a Buddhist altar** -- together with an incense burner, a kōgō, one or a pair of candlesticks, and one or two small flower arrangements) -- along with the name-tablets of deceased members of the family. Possibly a kinran or brocade altar-cloth would have been spread underneath the censer, with a valance and curtains (suspended from the otoshi-gake [落し掛]) surrounding the butsu-dan on three sides.

Shibayama's version provides the reader with a little more clarity: san-bō ni hisashi tsuke-mawashi, shōmen ni toko ji-butsu wo kamaetaru jūkyo nari [三方ニヒサシツケ廻シ、正面ニ床持佛ヲ構ヘタル住居也].

San-bō ni hisashi tsuke-mawashi [三方に庇付け廻シ] means on three sides hisashi were attached around (the two-mat room's) periphery.

Shōmen ni toko ji-butsu wo kamaetaru jūkyo nari [正面に床持佛を構えたる住居なり] means a dwelling (or residence)†† in the forward part of which the ji-butsu (i.e., the butsu-dan [佛壇]) was enclosed within the toko.

That is, the butsu-dan on which the image and ancestral tablets were displayed was enclosed within the tokonoma.

__________

*Tanaka Senshō, however, argues that buildings of this sort generally have hisashi on all four sides, which provide seating for various people who are participating (in an inferior capacity) in the ritual. Only the principal descendant of the departed, and the monks who were chanting the prayers, would enter the ji-butsu-dō.

†Presumably, shōmen [正面] means the side of the room that functioned as its focal point.

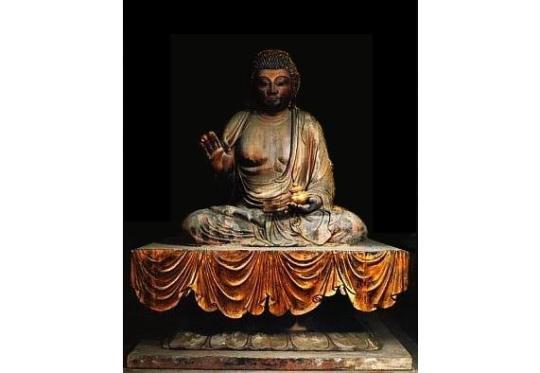

‡Today this would invariably be Shakyamuni (Siddhārtha Gautama), but the idea of ji-butsu also allows a representation of the Buddha (or even a Bodhisattva) to which one is particularly devoted -- in the case of most chajin of Rikyū's day, this would have been Amitābha (Amida [阿彌陀]) as the Lord of the Pure Land and the principal Buddha of the Ikkō-ichi-nen-shū [一向一念宗].

Though even Bhaiṣajyaguru (Yaku-shi nyorai [藥師如來]), the Bodhisattva of Healing (shown above) under whose protection chanoyu is included (and who is often depicted holding a small jar, like a chaire, in his left hand).

**While I have shown the butsu-dan extending across the entire width of the room, many of the commentators make the tokonoma 3-shaku, 4-shaku, or 4-shaku 2-sun wide, with the butsu-dan reduced accordingly. Some even envision a circular opening in the wall, covered by a pair of small shōji that open onto a recess wherein the Buddha statue and its accompanying objects were enshrined.

While these various representations imitate what is seen in the Sen families’ sō-dō [祖堂], they would be more appropriate to the Edo period than to Rikyū’s day. Rikyū would probably have used a rather long, somewhat narrow, table that extended across the width of the room (as I have shown) -- based on the way things have traditionally been done, with respect to ancestor-worship altars, in both China and Korea.

††Jūkyo [住居] means a residence or dwelling. Whether this is referring to Rikyū's compound, or to the toko (as the place where the ji-butsu “resides”), is unclear.

³Ekō kokorozashi no kuyō-bi ni ha, kanarazu oshō narabi ni kono-bō wo manekare-shi ni [囘向心ザシノ供養日ニハ、カナラズ和尚幷コノ坊ヲ招カレシニ].

Ekō [回向]* means to hold a memorial service (for a departed person).

Kokorozashi [志]†. Shibayama explains this usage in the following way:

sono seisha ni kokoro wo mukuru i ni te, ki-nen to iu ni onaji‡

[其逝者ニ心ヲ向クル意ニテ、記念ト云フニ如ジ].

“The meaning is to turn one’s thoughts to the deceased; it is the same as saying to commemorate or honor the memory of (someone).”

Kuyo-bi [供養日]: kuyo [供養] is a Buddhist term meaning a memorial service. Kuyo-bi [供養日], then, would name the day of the memorial service.

Kanarazu oshō narabi ni kono-bō wo manekare-shi ni [必ず和尚ならびこの坊を招かれしに] means certainly (kanarazu [必ず]) oshō** [和尚], and also (narabi ni [ならびに]) this monk††, would be invited (manekare-shi [招かれしに]).

In other words, Rikyū had the desire that, as a way to do honor to the deceased, he would always invite ōsho [和尚] and Nambō Sōkei to the memorial service. Apparently with the intention that they chant prayers during the offering of tea at the altar.

Shibayama’s text suggests a slightly different interpretation might be in order: ekō kokorozashi no kuyō-bi ni ha, kanarazu kore ni te oshō narabi ni kono-bō wo manekite cha ari-shi ni [回向志ノ供養日ニハ、必コレニテ和尚幷ニ此坊ヲ招キテ茶アリシニ].

This means on the memorial day on which Rikyū turned his thoughts to the performance of the commemorative service, (he) would certainly invite oshō and this monk for tea on this occasion.

Perhaps he is thinking of hosting a chakai for the two monks after the service is finished (as a way to express his thanks for their presence and prayers)?

__________

*Ekō [囘向] uses one of those strange kanji variants that became fashionable during the seventeenth century.

†Kokorozashi [心ざし], as this word is written in the Enkaku-ji text, is the same nonstandard form found in the preceding (and other) entries -- suggesting that they were either written or edited by the same individual or group.

‡Onaji [如じ] is possibly a variant (and non-standard) way of writing the word onaji [同じ]. It is equivalent to gotoshi [如し], meaning “the same as.”

**According to Hisamatsu Shin-ichi [久松真一; 1889 ~ 1980] sensei, the editor of the Sadō ko-ten zen-shū [茶道古典全集] version of the Nampō Roku, the title oshō is referring to Shōrei Sōkin [笑嶺宗訢; 1505? ~ 1584].

However, Hideyoshi's Jurakudai (in which the most likely version of Rikyū’s two-mat room seems to have made its first known appearance) was not completed until 1586. In that case, and assuming that this particular ji-butsu-dō is the one that would have been built somewhere on the grounds of Rikyū's residence there, oshō would more likely refer to Kokei Sōchin 「古溪宗陳; 1532 ~ 1597].

Perhaps it should be added that, while Shibayama Fugen says nothing regarding the supposed identity of this “oshō,” Tanaka Senshō agrees with Hisamatsu sensei’s assessment.

††In other words, Nambō Sōkei.

⁴Ji-butsu no uchi, ko-dōgu in-kazu in-kane nari-shi hodo ni tazune-sōroeba, anagachi ni sono sata ni mo oyobu-bekarazu to ha no tamai-shi nari [持佛ノ内、小道具陰數陰カネナリシホドニ尋候ヘバ、アナガチニ其沙汰ニモ及ベカラズトハノ玉シ也],

Ji-butsu no uchi [持佛の内] means within the ji-butsu-dō.

Ko-dōgu in-kazu in-kane nari-shi [小道具陰數陰カネなりし]: according to the previous entry, ko-dōgu [小道具] refers, in this context, to the chaire and the temmoku. The number of these things should be an even number*, and they should be displayed on yin-kane.

Hodo ni tazune-sōroeba [ほどに尋候えば] means if (you) should ask the reason for this -- in other words, if you should feel inclined to ask about why only the chaire and chawan need to conform to the yin-kane (rather than all of the other utensils).

Anagachi ni sono sata ni mo oyobu-bekarazu to ha no tamai-shi nari [強ちにその沙汰にも及ぶべからずとはの給いしなり]: anagachi ni [強ちに] means (not) necessarily, (not) always; sono sata ni mo [その沙汰にも] means also (when) handling† such things; oyobu-bekarazu [及ぶべからず] means should not go beyond (something), should not exceed (something).

In other words, this is saying that it is not necessary for anything but the chaire and chawan to be associated with a yin-kane in order to achieve a yin arrangement‡.

__________

*Meaning that both the chaire and the chawan should be displayed together. Placing out the chaire only (and carrying in the temmoku later), for example, would be a violation of this rule.

†Specifically, deciding what is right -- as opposed to what is wrong -- in a given setting or situation.

‡Preparing tea in memory of a departed person requires a yin arrangement.

Whether the host is using a daisu, or arranging the utensils directly on the mat, the positions of the other utensils -- the furo or (in the case of a 2-mat room) mukō-ro, the mizusashi, and so on, are mostly fixed, and cannot be changed.

⁵Aru-toki Sen’ami no nenki-no-hi ni, ko-nasubi ni te cha-taterareshi ni ha in no hitotsu-mono nari [アルトキ千阿彌ノ年忌日ニ、小ナスビニテ茶立ラレシニハ陰ノ一物也].

Aru-toki Sen'ami no nenki-no-hi ni [ある時千阿彌の年忌日に]: aru-toki [ある時] means on one occasion*; Sen’ami† nonenki-no-hi ni [千阿彌の年忌日に] means on the day of the anniversary of Sen’ami's death.

Ko-nasubi ni te cha-taterareshi [小茄子茶入にて茶立られし] means that Rikyū prepared tea (during the memorial service) using a small nasu-chaire‡.

In no hitotsu-mono [陰の一物] means that Rikyū displayed this chaire so that it was resting squarely on a yin-kane** -- with the implication being that this was done as a gesture of respect (both for Sen’ami, and for the chaire).

Shibayama Fugen's version of the text has aru-toki Sen’ami no nenki-hi ni, ko-nasu ni te cha-taterareshi ni ha, in no hitotsu-mono ni okare-shi nari [或時千阿彌ノ年忌日ニ、小茄子ニテ茶立ラレシニハ、陰ノ一物ニ被置シナリ]. But aside from the minor changes in punctuation, and the final okare-shi [被置し = 置かれし] (this verb only states what is already obvious from context) -- all of which help the reader arrive at the correct understanding -- the basic meaning remains the same.

___________

*The implication being that Rikyū used a different set of utensils on every occasion, or at least changed them frequently enough that the author thought this was worth a mention.

This, of course, fits into the ideas that the bakufu was promoting during the first century of the Edo period. For that matter, so does the idea of venerating ones ancestors -- by constructing a dedicated memorial oratory (sō-dō [祖堂]) of some sort (something that remained fairly common, at least among the middle to upper classes in Japan, until fairly recently).

†Sen’ami [千阿彌] was supposed to have been Rikyū's grandfather (though “grandfather” is often used more loosely to mean progenitor or ancestor, regardless of the actual number of generations that separate said person from the present). While modern Sen family mythology states that he was one of the dōbō [同朋], “companions,” serving the Ashikaga shōgunate, his name does not seem to appear in any of the relevant records from that period.

Since the dōbō-shū seem to imitate a similar sort of system that provided training and advice to the Koryeo kings, and (perhaps more importantly) because Rikyū began to voice this understanding of his ancestry only after he returned to Japan from his stay on the continent, the possibility should be considered that Sen’ami was a functionary of the Koryeo court. (A possibility that most Japanese tea people, at least, would find repulsive -- given the ties between modern day chanoyu and the ultra-nationalist camp that has ruled the Japanese nation since the beginning of the 20th century, and which has been largely responsible for rewriting Japanese history as a repudiation of the archaeological and anthropological studies conducted by western-trained Japanese scholars during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in both Japan and Korea.)

‡While this seems to be a direct allusion to the preceding entry, and while Rikyū did own a ko-nasu chaire, his chaire measured just over 2-sun in diameter, rather than the 1-sun 5- or 6-bu that was prescribed there.

Interestingly, in the Taishō mei-ki kan [大正名器鑑], Takahashi Sōan states that this chaire was the model for Rikyū's small natsume made by Seiami [盛阿彌] (Hideyoshi's principal lacquerer) -- that is, the shape of the lower part of that natsume (up to the point of maximum diameter), as well as its height and diameter, were based on this small nasu-chaire.

**This seems to be an allusion to the mitsu-gumi arrangement that was discussed in the previous entry (though it is unlikely that Rikyū performed that sort of chanoyu in his ji-butsu-dō).

0 notes

Photo

“ Mizuya Chaya “Tea House” this quaint thatched-roof teahouse is one of Nara's most atmospheric spots in the lush forest near Kasuga Grand Shrine “

📷 @tomokotoamu

Via japan_inside

0 notes

Text

Only in Japan: Burning a Mountain as a Celebration

On the fourth Saturday of each January, the dead grass of Mount Wakakusa is set ablaze as part of a unique and impressive festival called Wakakusa Yamayaki (‘Wakakusa Burning Mountain’).

No one known exactly how the tradition of burning an entire 342-metre-high hill in Japan’s Nara Prefecture actually started, but one thing is for certain – it has been around for hundreds of years. Some say it began as a boundary dispute between the two greatest temples of Nara, Tōdai-ji and Kōfuku-ji, sometime during the 18th century. When mediation failed, the entire hill was burned to the ground, although no one quite remembers how that solved anything. Another theory claims that the annual fire originated as a way to eliminate pests and drive away wild boars. Today, it’s just an impressive sight to behold that attracts tourists from all over the world.

Wakakusa Yamayaki starts early in the day, with a competition of giant rice cracker throwing. It’s not until 5 pm that a procession departs from the Tobino area of Kasuga Taisha towards Mount Wakakusa, stopping at the Mizuya Shrine along the way in order to light the torches. At around half past five, the procession arrives at the base of the hill and a large bonfire is lit. After a 15-minute fireworks display, torches are lit from the bonfire and the dead grass is set ablaze.

https://www.instagram.com/p/Bef5rVtFuY0/?utm_source=ig_embed

Depending

Read the full article

0 notes

Photo

The Wakakusa Yamayaki is an annual festival during which the grass on the hillside of Nara's Mount Wakakusayama is set on fire. The mountain is located at the eastern end of Nara Park, and when it is set alight it can be seen throughout the city. The burning of the mountain itself is preceded by a fireworks display. The festival takes place every year on the 4th Saturday of January, but may be delayed to a later date in case of bad weather.

Todaiji Temple, Kofukuji Temple and Kasuga Shrine are all involved with the ceremonies of the festival. The Wakakusa Yamayaki has been taking place for hundreds of years and its precise origins are unclear. One theory claims that the burning of the mountainside began during boundary conflicts between Nara's great temples, while another claims the fires were used to drive away wild boars.

The festival officially begins at noon, after which a variety of minor events take place around the base of Wakakusayama. The most interesting minor attraction is a throwing competition of giant rice crackers (sembei) that takes place from 12:30 to 15:00. Travelers will recognize the sembei as giant versions of the rice crackers that are on sale throughout Nara Park as food for the wild deer.

Around 17:00, a procession of people involved in lighting the mountain on fire departs from the Tobino area of Kasuga Taisha towards the mountain, making a stop at the Mizuya Shrine along the way in order to light the torches. Around 17:30, the procession arrives at the base of Wakakusayama where several hundred spectators have already gathered, and a large bonfire is lit part way up the mountainside, just past the barrier restricting access to the public

0 notes

Text

Siddhārtha Gautama

The path to the Enlightenment is winding but rich of surprises. Main entrance to Toyokuni Shrine, Kyoto Paths out of Mizuya Shrine, Nara Through the wooden corridors of Itsukushima Shrine, Miyajima island Low tide at Itsukushima Shrine, Miyajima island The greatest Buddha (Siddhārtha Gautama) of Nara View on Kyoto from the uphill Kiyomizu-dera Temple Click to zoom in each picture. This photo…

View On WordPress

#2 weeks guide through japan#2 weeks in japan#Artborghi Japan of mine#artborghi japan photoreportage#experience japan#great Buddha of Nara#Japanese Buddhism#lorenzo borghi japan of mine#photography in japan

0 notes

Text

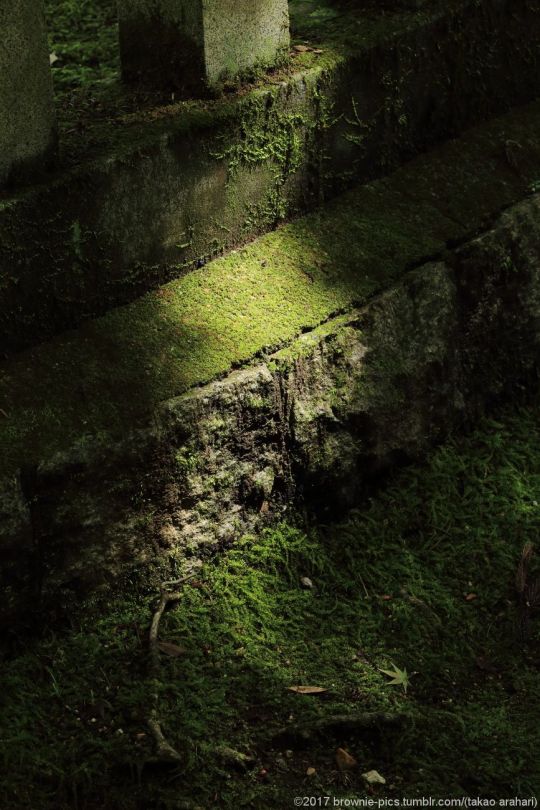

’23.12.17 飛火野、春日野園地、手向山八幡宮、水谷神社付近にて

一昨日は日中20℃越え、昨日は雨。そして今朝は4℃弱・・

滅茶苦茶な気温の乱高下でしたが、ようやく初冬を迎えたような・・。

風が冷たく、涙がちょちょぎれてじわっと鼻水なんかも出てきます💦

#奈良#nara#奈良公園#nara park#日本#japan#飛火野#tobihino#春日大社#kasuga tasiha shrine#春日野園地#kasugano enchi#手向山八幡宮#tamukeyema hachimangu shrine#東大寺#todaiji temple#水谷神社#mizuya shrine#photographers on tumblr#natgeoyourshot

136 notes

·

View notes

Photo

このブログを書いている今日’22.6.17、父親を送り出してきました。

暫くは何かと慌ただしくなると思うので、レスや投稿滞るかもしれません。

・・とはいえ、ばたばたストレス蓄積したら衝動的に発散取材・発散投稿の可能性も大アリですが💦

当分は片付けと回想の両軸メインで過ごすことになりそうです。

写真は‘22.6.4 水谷神社、春日大社にて

#奈良#nara#日本#japan#奈良公園#nara park#水谷神社#mizuya shrine#春日大社#kasuga taisha shrine#鹿#deer#初夏#early summer

174 notes

·

View notes

Text

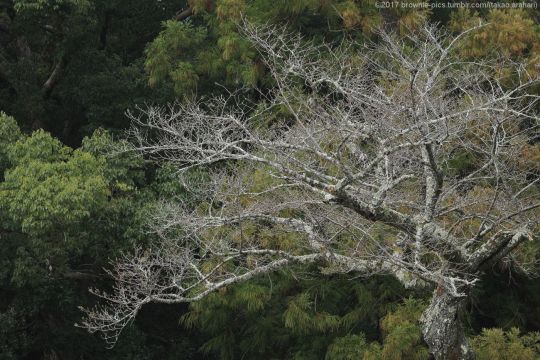

'24.3.17 飛火野、春日野園地、水谷茶屋周辺にて

奈良はお水取りが終わった途端、日中の気温が20℃近くに。まさに春を呼ぶと言われるお水取りのこの実力・・。

でも木々はまだ沈黙の時期。ですが枝先などにじわっと少しずつ春の準備を行っているようです。

もう少しすれば、木々は花や新緑を盛大に纏い、饒舌に春を語り始めることでしょう・・僕もそれを待っています。

#奈良#nara#奈良公園#nara park#日本#japan#飛火野#tobihino#春日大社#kasuga tasiha shrine#春日野園地#kasuhgano enchi#水谷茶屋#mizuya tea house#晩冬#late winter#木々#forest#photographers on tumblr#natgeoyourshot

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

'23.12.3 水谷茶屋、手向山八幡宮、東大寺二月堂にて

@masachi さん、@neko-no-oto さんとの奈良公園ツアー、遅いお昼食べて後半戦です。

禰宜道から春日大社を通り、masachiさんがまだ登ったことが無いとのことで二月堂の舞台へ。陽が傾いてきました・・

#奈良#nara#奈良公園#nara park#日本#japan#春日大社#kasuga tasiha shrine#水谷茶屋#mizuya tea house#東大寺#todaiji temple#二月堂#nigatsudo hall#鹿#deer#紅葉#atumn leaves#秋#atumn#photographers on tumblr#natgeoyourshot

110 notes

·

View notes

Photo

‘22.11.23 若宮神社・春日大社・水谷茶屋・手向山八幡宮にて

本当ならTumblr繋がりの方々と奈良公園の散策を企てていた日。

ピンポイントで当日のみ雨予報ということで、泣く泣く延期。前日から撮影モードに入ってた僕は地元の強みもあって、とりあえず出かけました。

やはり雨がしんしんと降っていて、若宮さん、春日さんと屋根あるとこ伝いに移動。こんな日にわざわざ撮りに来てるの僕ぐらいだろうなぁと思ってたらインスタ繋がりの写友さん登場w。お互いもの好きだなぁww。

そんな訳で2人で傘差して撮りつつ北へ移動。ぐるっと公園内周って南大門辺りで別れました。

機材や服に気を使いますが、これはこれで楽しいですw。

#奈良#nara#日本#japan#奈良公園#nara park#若宮神社#wakamiya shrine#春日大社#kasuga taisha shrine#水谷茶屋#mizuya tea house#手向山八幡宮#tamukeyama hachiman-gu shrine#子鹿#fawn#紅葉#autumn leaves#秋#autumn#雨の日#rainy day#photographers on tumblr

344 notes

·

View notes

Photo

‘22.11.23 春日大社、水谷茶屋、手向山八幡宮にて

お蔵の秋写真出しますw。幻の撮影会当日に撮った写真です。

少し前の投稿とほぼ同じ場所と時間の流れなんですが別カットということで。

・・Tumblrの投稿フォーム、新しいバージョンができたみたいなんですが、写真30枚投稿できるとか?・・ちょっと使い方分からなかったので従来のフォームで投稿しますが、枚数の自由度増えるならありがたいかも。

#奈良#nara#日本#japan#奈良公園#nara park#春日大社#kasuga taisha shrine#水谷茶屋#mizuya chaya tea house#手向山八幡宮#tamukeyama hachinmangu shrine#秋#autumn#紅葉#autumn leaves#photographers on tumblr#natgeoyourshot

188 notes

·

View notes

Photo

‘21.10.30 春日大社、水谷茶屋付近、手向山八幡宮、二月堂にて

Chu-nens徘徊ツアー、続編ですw。春日さんから若草山の麓を通っていつもの手向山八幡宮へ。@moji-2 さんとあれこれ談笑しながら撮り歩きます。ISO上がっても気にせず手持ちでさくさく撮ってくのも楽しい。

そしてこれまた定番の二月堂へ到着。下から舞台を見上げると濃い青空が。

#奈良#nara#日本#japan#奈良公園#nara park#春日大社#kasuga taisha shrine#水谷神社#mizuya shrine#手向山八幡宮#tamukeyama hachinmangu shrine#東大寺#todaiji temple#鹿#deer#烏#crow#秋#autumn

349 notes

·

View notes

Photo

‘21.8.29 水谷神社付近にて

先の投稿で、カラスさんと鹿さんが一緒に写ってる写真について興味を持たれた方が多かったので両者の関係が分かるようなショットをお蔵から放出w。ちなみにこの牡鹿さんは先の投稿で出ていたのと同じ鹿さんです。

カラスさんは鹿さんの毛をつんつんと拝借して自分の巣の材料にするんです。鹿さんも慣れてるのか、意に介せずカラスさんの好きなようにさせています。

カラスさんの巣作り時期と鹿さんの冬毛が抜け替わるタイミングが重なる春によく見られる光景なんですが、夏の終わりの今、カラスさんは巣のリフォームでも行っているのでしょうか・・。これもある種のリサイクル活用ですねw

#奈良公園#nara park#鹿#deer#烏#crow#鹿の毛#deer hair#巣の材料#one of the materials for the crow's nest#春日大社#kasuga taisha shrine#水谷神社#mizuya shrine

436 notes

·

View notes

Photo

‘21.9.5 手向山八幡宮、若草山の麓、水谷神社付近にて

まだ続きますww。リプライも遅れてすみません・・。とりあえず何か投げかけたい気分なもので・・。

暑さも少し和らいだ、夏と秋の狭間の公園をぶら~ぶら~ぶら~と撮り歩くのが気持ちいいです。

https://youtu.be/0rvqWa8Mnsg

あ、上の曲は画像のイメージとは全く違います💦、タイトル思い出して添付しました。ぶらぶらの意味も違いますし・・でもカッコいい曲ですよ、好きなバンドですw。

188 notes

·

View notes

Photo

‘21.4.18 春日大社・水谷神社にて

最近撮ったものを投稿しようとしたらチョイスにやたら迷う。少し寝かせてから見直した方がいいのかな・・。

320 notes

·

View notes