#sudanese photographers

Text

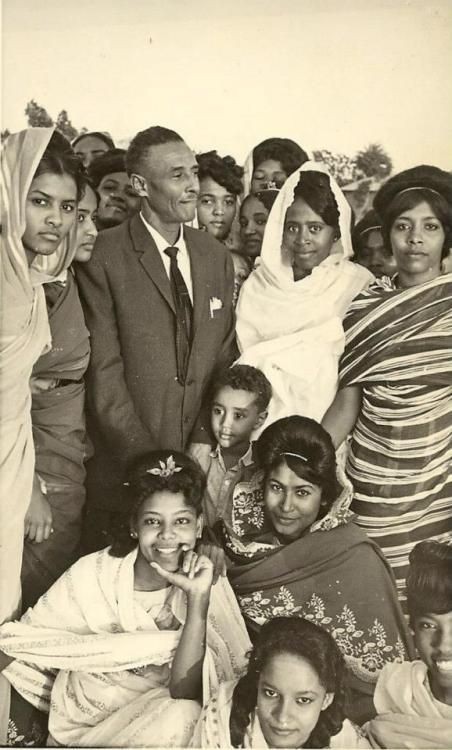

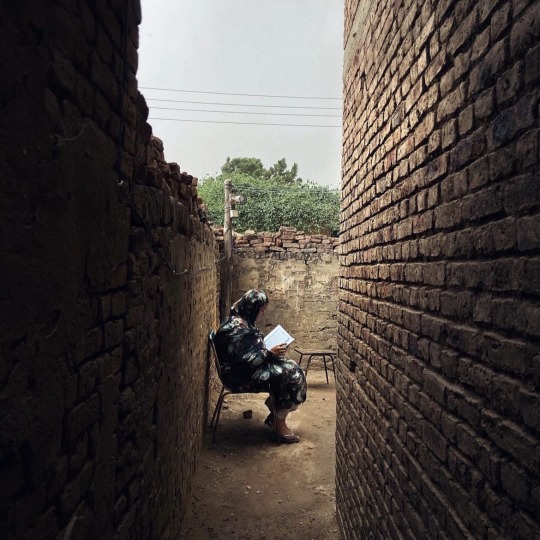

A group of students in Omdurman - 1967

#sudan#sudanese#السودان#photography#vintage#vintage sudan#sudanese culture#photograph#sudan archives

170 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Contemporary Lens

Shaheen & Bari

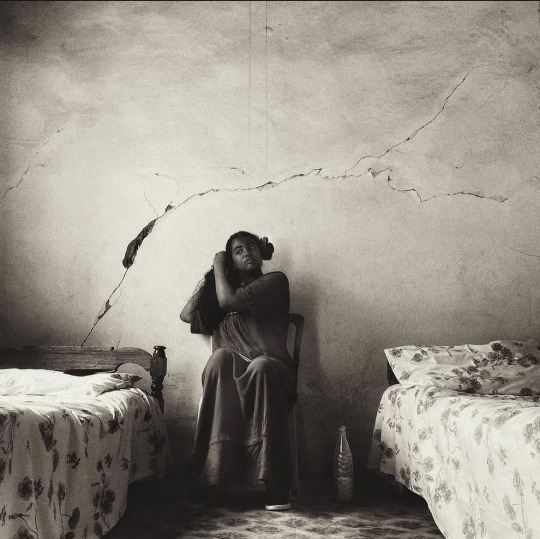

From the series The Muslim In-Between by Suleika Mueller © Suleika Mueller

Suleika Mueller

Born in Switzerland, Suleika Mueller was brought up in a Sudanese Sufi Muslim order, spending formative years going to a Swiss school whilst continually traveling to Sudan, Egypt, the UAE or across Europe to practice with the Sufi community. This experience – of living between two cultures – led the photographer to become interested in hybrid identities. Now, based in London, Mueller uses the lens to make space for such individuals to express themselves (above right). She is dedicated to “creating more nuanced and authentic Muslim portrayals and stories, as well as educating and challenging harmful stereotypes.”

#suleika mueller#photographer#artist#art#shaheen & bari#the muslim in-between#photo series#sudanese sufi muslim order#switzerland#muslim#islam

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dark skin ethnic black Sudanese model Alek Wek joyful excited smile beauty photography ❤️

"Elegance in Diversity: The Radiant Smile of Sudanese Beauty Alek Wek captured in Joyful Photography ❤️📷✨"

#Cultural representation#Empowering black beauty#Sudanese heritage pride#Alek Wek's captivating smile#Photographic allure#Ethnic identity celebration#Melanin-rich elegance#Expressive joy#Diversity in beauty#Model's magnetic charm#Dark skin positivity#Authentic ethnic portrayal#Cultural enrichment#Vibrant photographic moments#Inclusive fashion industry#pretty girl#beautiful women#pretty woman

0 notes

Text

“A Sudanese girl holds a sign as supporters of Sudan People's Liberation Army leader John Garang wait for his arrival on the tarmac of the Rumbek, south Sudan, airport.”

Photographed by Beatrice Debut.

10 June 2004.

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Sudanese weddings, photographed by Zofa

#zofa#ph#sudan#africa#north africa#african culture#sudanese#sudanese weddings#sudanese culture#love#couples#wedding photography#african#zofa photography

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

More than a dozen black models have declared they are boycotting Melbourne Fashion Week (MFW) in response to multiple instances of racism they have experienced across the wider Australian fashion industry.

The 13 models – some of whom turned down offers to appear at MFW, while others refused to participate in casting calls – are using next week’s landmark fashion event to draw attention to their experiences of racism in the industry, including claims they are being paid significantly less than white models, the N-word being used by a photographer, and hairdressers talking in derogative terms about African hair.

“In London, New York and Paris, you could not get away with what the fashion industry is doing here and how it treats black models, but they don’t seem to care or want to change,” South-Sudanese-born model Nylow Ajing told this masthead.

“Black models doing Australian fashion is a form of self-destruction”, said Awar Malek, a 24-year-old Sydney-based model. “It is absolutely the most traumatising, and dehumanising, underpaying, and overall mentally draining week and I have no desire to continue to participate.”

Dehumanising’: Models announce boycott amid fashion industry racism claims | Antoinette Lattouf and Osman Faruqi

#awar malek#Nylow Ajing#sudanese#south sudanese#sudanese (south)#Nyaluak Lethe#adut akech#Duckie thot#racism

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

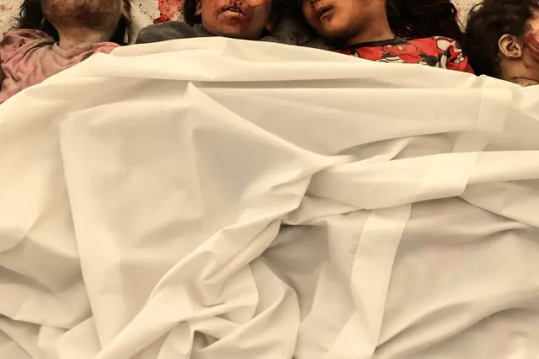

About these Gaza photographs by Mahmud Hams (top) and Mohammed Salem (bottom), Lydia Polgreen writes:

"And so I ask you to look at these children. They are not asleep. They are dead. They will not be part of the future. But know this: The children in the morgue photo could be any children. They could be Sudanese children caught in the crossfire between two feuding generals in Khartoum. They could be Syrian children crushed under Bashar al-Assad’s bombs. They could be Turkish children who died in their beds when a shoddily constructed apartment block collapsed upon them in an earthquake. They could be Ukrainian children slain by Russian shells. They could be Israeli children slaughtered in a kibbutz by Hamas. They could be American schoolchildren gunned down in a mass shooting. These children are ours."

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The actual number of casualties continues to be disputed and none of the victims have been identified in last week's tragedy.

Human rights organizations are calling for an independent investigation into the clashes that occurred at the border of Morocco and the Spanish territory of Melilla earlier last week.

It was first reported that 23 people were killed in what witnesses say was a “a bloodbath,” according to The Guardian.

However, Morocco's Human Rights Association contested the official death toll, reporting instead that 27 migrants had died, while the Spanish NGO Walking Borders is reporting 37 fatalities, ABC News reported.

About 2,000 migrants, mainly from sub-Saharan Africa, attempted to cross into one of the EU’s two land borders with Africa last Friday when the migrants reportedly tried to climb fences at a checkpoint at the border, The Guardian reported.

During the melee, authorities began attacking the refugees, reports said.

“Some fell from the top of the barrier [separating the two sides],” a Moroccan official said following the incident, according to The Guardian.

The Guardian reported that 140 security personnel and 76 migrants were injured during the attempt to cross.

Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez told The Associated Press the mass crossing onto his border was a “violent assault” and “an attack on the territorial integrity of Spain.”

He also blamed the “mafias that traffic in human beings.”

However, a person named Mohamed, one of those who managed to get across spoke to the press and said otherwise.

“There are no mafias, we don’t have money to pay them. We organize ourselves,” he told broadcaster RTVE.

Since the tragedy, Human Rights Watch as well as Moroccan and Spanish organizations, UN Human Rights Commissioner Michelle Bachelet, and the African Union have all called for an inquiry.

“Video and photographs show bodies strewn on the ground in pools of blood, Moroccan security forces kicking and beating people, and Spanish Guardia Civil launching teargas at men clinging to fences,” said Judith Sunderland, acting deputy Europe and Central Asia director at Human Rights Watch said in a statement. “Officials in Spain, Morocco, and the European Union should condemn this violence and ensure effective, impartial investigations to bring justice for those who lost their lives.”

The dead were among as many as 2,000 people who attempted to cross into Melilla early last Friday. Melilla and another Spanish enclave, Ceuta, are the only land borders between Africa and Europe.

Moroccan authorities said 23 people died, blaming a “stampede” and people falling from a high fence. Local NGOs put the number as high as 37, saying security forces turned violent and failed to secure treatment for the injured in the hours after they were hurt.

More than 130 people managed to reach Spain and are being held in reception centres there, with one Sudanese man telling journalists he had tried to cross the Mediterranean Sea three times from Libya to Europe before moving on to Morocco. More than 17,000 people have died or disappeared trying to cross the central Mediterranean Sea since 2014, according to the International Organisation for Migration, while nearly 100,000 have been intercepted since 2017 and forced back to Libya.

179 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paul Jung

Images part of 2015 b/w editorial for Suited mag, featuring four South Sudanese models, Mari Malek & Mari Agory (this img) and Atong Arjok & Nykhor Paul.

Stylist: Jessica Willis

Paul Jung is a New York based photographer, originally from Taiwan. With a background in art, architecture and graphic design, he focused on fashion photography.

https://fashionfav.com/magazine-editorials/suited-magazine-spring-2015-model-citizens-by-paul-jung/

https://trendland.com/paul-jung-for-suited-magazine/

https://www.ignant.com/2016/09/01/fashion-photography-by-paul-jung/

thnx celiabasto

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Family Pictures,

By: Sudanese photographer "Rashid Mahdi (1923-2008)"

#sudan#sudanese#السودان#photography#vintage#vintage sudan#sudanese culture#sudan archives#photograph#family#Sudanese family

205 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Martha Singing

Martha is a member of the Bendigo South Sudanese Ensemble, formed in 2019. Every week they would come together to ideate, compose, sing and practise their craft, working towards a performance celebrating their culture and heritage. The photo was taken in The Engine Room, a black box performance space that is quite disorienting to be in when the lights are low. I wanted a sense of the subjects floating in the space, emphasising the feeling of being cut off and isolated by the pandemic

Photograph: Michael Wolfe

#michael wolfe#photographer#martha singing#bendigo south sudanese ensemble#performance#celebration#culture#heritage#the engine room

0 notes

Text

Dark skin ethnic black Sudanese model Alek Wek joyful excited smile beauty photography ❤️

"Capturing Pure Joy: The Infectious Smile of Sudanese Beauty Alek Wek in Stunning Photography ❤️📷✨"

#Ethnically diverse beauty#Black model representation#Sudanese cultural heritage#Alek Wek's radiant smile#Photographic charm#Ethnic pride#Dark skin elegance#Excitement and beauty#Joyful expression#Empowering diversity#Cultural identity celebration#Authentic ethnic portrayal#Model's captivating presence#Melanin-rich beauty#Cultural inclusivity in fashion#beautiful women#pretty woman#pretty girl

0 notes

Text

A Sudanese girl wearing facepaint reading in Arabic "fall again" chants slogans during a demonstration demanding a civilian body to lead the transition to democracy, outside the army headquarters in the Sudanese capital Khartoum on April 12, 2019.

Photographed by Ashraf Shazly.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

15 March 2023

King Charles III spent time speaking to members of the Sudanese community in London today to bear witness to their testimonies of the conflict in the region and to hear about their lives in Sudan and now in the UK.

The King was shown photographs, drawings and objects brought from Sudan. His Majesty met Sudanese women who decorate pieces of fabric to create a giant toub; an empowerment and peacebuilding project which aims to bring the UK's Sudanese community together as a visual representation of unity and solidarity.

The King was accompanied by Amouna, a survivor of the conflict in Darfur.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

War and Peace Series by Sudanese photographer Jood Ahmed

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Early on June 15, 2023, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) attacked a makeshift medical clinic in West Darfur’s capital, El Geneina, where 25 injured patients were seeking treatment. Ali, who had been shot in the leg during a previous attack, described what happened: “They started shooting at us and killed everyone except me and a woman [who was also wounded]. They shot me in the right arm. I slumped over, pretending I was dead.”

Ali and the woman stayed in the clinic, surrounded by the corpses of the patients and medical workers, for ten hours, as the RSF continued their assault on the city. At around 5 p.m., another group of seven armed men in uniform entered the clinic. “One saw that I was alive and came up to me and smashed his hand on my broken leg,” Ali recalled. “I said: ‘Please stop! Just kill me instead!’ He said: ‘We won’t kill you! We want to torture you, Nuba! We got rid of most of your family, and no one is here to care for you.’” Ali was rescued by his family hours later after the forces had left the clinic.

From late April until early November 2023, the RSF and allied militias conducted a systematic campaign to remove, including by killing, ethnic Massalit residents, such as Ali, from El Geneina, home to an ethnically mixed population of around 540,000 people. Violence began on April 24 and continued in phases over seven weeks, peaking in mid-June, with another surge in November. The massacre that Ali survived was just one in a deluge of atrocities that the RSF and allied militias, predominantly from Darfuri Arab groups, have carried out in El Geneina and West Darfur in general since the outbreak of the conflict between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the RSF on April 15, 2023.

The events are among the worst atrocities against civilians so far in the current conflict in Sudan. The total number of dead is unknown. Sudanese Red Crescent staff said that on June 13, they counted 2,000 bodies on the streets of El Geneina and then, overwhelmed by the numbers, stopped counting. Two days later, on June 15, a large-scale massacre took place. The UN panel of experts on the Sudan estimated, citing intelligence sources, that between 10,000 and 15,000 people were killed in El Geneina in 2023.

This report provides an account of how the Rapid Support Forces and allied forces committed numerous serious violations of international humanitarian and human rights law as part of their campaign against the Massalit people of El Geneina. It is based on over 220 interviews, verification and assessment of 110 photographs and videos, and analysis of satellite imagery and documents shared by humanitarian organizations. Between April and November 2023, researchers interviewed recently displaced residents of El Geneina in person during six trips to Chad, Kenya, Uganda, and South Sudan, and also conducted supplementary telephone interviews.

Most interviewees were Massalit civilians. They included victims and witnesses, medical and humanitarian workers, lawyers, human rights activists, religious figures, and former government officials. Researchers also interviewed Massalit men who were current and former members of law enforcement or armed groups, 38 Arab residents of El Geneina as well as international aid workers and analysts.

A short bout of clashes broke out on April 24 between the SAF and the RSF, and then the RSF and allied militias attacked majority Massalit neighborhoods. They clashed with predominantly Massalit armed groups, including forces from the Sudanese Alliance, led by the late state governor, Khamis Abdallah Abbakar, as well as Massalit men—primarily youth—loosely organized and mobilized in local “self-defense groups.”

Over the next weeks, and even after Massalit armed groups lost control of their neighborhoods, the RSF and allied militias systematically targeted unarmed civilians, killing them in large numbers. Adolescent boys and men were especially singled out for killings, but among those unlawfully killed were also many children and women. The RSF and allied militias also appear to have targeted injured people as well as prominent members of the Massalit community, including lawyers, doctors, human rights defenders, academics, community leaders, religious figures, and local government officials.

Women and girls were raped, and detainees were tortured and otherwise ill-treated. The RSF and allied militias methodically destroyed civilian infrastructure. They looted on a grand scale, and they burned, shelled, and razed neighborhoods to the ground, homing in on neighborhoods and sites, including schools, hosting primarily Massalit displaced communities.

Thousands of civilians, mostly men and adolescent boys, but also younger children including babies, older people, and women were killed in less than two months, and thousands more were injured. A retrospective mortality survey conducted by Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders, MSF) in three refugee camps in eastern Chad concluded that there were 167 violent deaths in the households of 6,918 people from El Geneina. This amounted to a staggering mortality rate of 241 per 10,000 people, marking a 23-fold increase in the male mortality rate and a 11-fold increase in the women’s mortality rate.

During their campaign, RSF fighters and allied militias used derogatory racial slurs against Massalits and people from other non-Arab ethnic groups. They told them to leave, that the land was no longer theirs, and that it would be “cleaned” and become “the land of the Arabs.” Ahmad, 41, a Massalit man, recalled, in an interview with Human Rights Watch, forces telling fleeing civilians: “No Massalit people will live here!” and “No Nuba will live here!” and “No slaves will live here!”

Throughout the seven-week campaign, SAF soldiers largely hunkered down in their barracks, unable or maybe unwilling to protect the population. The UN Panel of Experts found that, “throughout the attacks, [the SAF] failed to protect the population.”

On June 14, the governor of West Darfur and leader of the Sudanese Alliance armed group, Khamis Abbakar, was killed. He was last seen in the custody of the RSF West Darfur commander, Gen. Abdel Rahman Joma’a Barakallah. His killing, coinciding with the collapse of Massalit forces’ ability to fight back against RSF attacks in primarily Massalit neighborhoods, led to a mass exodus from El Geneina. Some civilians and fighters tried to go west, toward Chad, only to come under attack by the RSF and militias. Many civilians and fighters then decided to flee toward Ardamata, a northern suburb of the city hosting a garrison of the Sudanese Armed Forces, leaving overnight in a convoy of tens of thousands of civilians and fighters.

In the early hours of June 15, the RSF and allied militias attacked the convoy as it proceeded through El Geneina, killing civilians in large numbers as they ran through the streets, tried to find refuge in homes and mosques, or attempted to swim across the seasonal Kajja river flowing through the city.

“My mom was pushing me in a wheelbarrow,” said Malik, an injured 17-year-old boy who was in the convoy when it came under attack. He said he saw RSF forces kill at least 12 young children, including infants, three men, and two women:

Two RSF forces… grabb[ed] the children from their parents and, as the parents started screaming, two other RSF forces shot the parents, killing them. Then they piled up the children and shot them. They threw their bodies into the river and their belongings in after them.

The killings continued over the following days in El Geneina and on the road to Chad, where tens of thousands of civilians, as well as Massalit fighters, headed in search of refuge.

On the road, the RSF and allied militias shot and killed or injured large numbers of civilians, including disarmed fighters. Arab civilians living in villages along the route to Chad extorted, beat, and harassed fleeing civilians. During the exodus, RSF forces sought to identify prominent Massalit community leaders, apparently to prevent them from reaching Chad.

Satellite imagery corroborates that, since the RSF and allied militias took control of El Geneina in June, predominantly Massalit neighborhoods have been systematically dismantled, many with bulldozers, preventing civilians who fled from returning to their homes.

In early November, nearly five months after the June 15 massacre, RSF and allied militias again killed at least 1,000 civilians in El Geneina’s suburb of Ardamata, according to the United Nations. The forces also looted civilian property and assaulted and unlawfully detained scores of predominantly Massalit people.

As a result of these atrocities, over 570,000 predominantly Massalit people, as well as members of other non-Arab groups, are now in refugee camps in Chad, with little hope of returning home safely in the near future.

Many abuses carried out by the RSF and allied militias documented in this report constitute war crimes and crimes against humanity. The targeting of Massalit people and other non-Arab communities with the apparent objective of at least having them permanently leave the region constitutes ethnic cleansing.

War crimes include the serious violations of international humanitarian law, or the laws of war, of intentionally directing attacks against the civilian population, intentionally directing attacks against civilian objects, and the intentional conduct of indiscriminate and disproportionate attacks. They also include pillage, torture, rape and other forms of sexual violence, murder and forcible displacement.

These acts were part of a widespread and systematic attack directed against the Massalit and other non-Arab civilian populations of majority-Massalit neighborhoods, and as such also constitute the crimes against humanity of murder, torture, and forcible transfer of the civilian population. The fact that the RSF and allied forces carried out these acts, constituting severe deprivation of fundamental rights, against the Massalit and non-Arab communities by reason of their ethnic identity, constitutes the crime against humanity of persecution.

The mass killings of ethnic Massalit civilians, and in particular the context in which these killings took place, also requires urgent action from all governments and international institutions to ensure investigation of whether the facts demonstrate a specific intent on the part of the RSF leadership and their allies to destroy in whole or in part the Massalit and other non-Arab ethnic communities in West Darfur, that is to commit genocide, and if so, to prevent its perpetration, and to hold those responsible for its planning and conduct accountable.

This report also documents how the SAF and the RSF’s use of explosive weapons in residential neighborhoods killed and endangered civilians, as well as killings, looting, and other abuses committed by Massalit fighters against Arab civilians. It also underscores the failure by the SAF and the Central Reserve Police (CRP), a militarized police unit, to protect civilians.

The politics of the conflict in Darfur have changed: In the 2000s, the Janjaweed—the Arab militias from which the RSF were formed—were armed by the military, which the RSF is now fighting across much of Sudan. But the abuses carried out in El Geneina felt all too familiar to many of the interviewees. Many recalled fleeing—sometimes as children—from their home villages in the 2000s, when they came under attack by the Janjaweed. The Darfur conflict of the 2000s killed and displaced many Massalit people. Survivors then found refuge in the camps for internally displaced persons (IDP) that swelled the population on the outskirts of El Geneina.

The Darfur conflict of the 2000s occurred against a backdrop of recurrent tensions over resources between non-Arab farming communities—including the Massalit, who claimed a historical right to the land in El Geneina—and Arab pastoralist communities. These tensions were instrumentalized by the government of Omar al-Bashir, who ruled until 2019. Over the past two decades, the proliferation of weapons in Darfur and the failure of successive governments to address grievances over land and political power at the state level, or to provide accountability for past violations, have allowed these tensions to fester.

Since 2019, Massalit people in West Darfur have come under renewed attack from Arab militias and the RSF. In 2020, following years of a progressive drawdown of peacekeeping forces from sites across Darfur, the United Nations Security Council ended the mandate of UNAMID, the joint African Union-United Nations peacekeeping force in the region, despite repeated warnings from displaced communities that this would remove a key deterrent to further attacks. Three large-scale attacks between 2019 and 2021 destroyed neighborhoods and IDP camps in and near El Geneina. Displaced persons, overwhelmingly Massalit, moved into the compounds of schools and official buildings in the inner city, which became known locally as IDP “gathering sites.”

These attacks led to the militarization of parts of the Massalit community. Young adults and adolescent boys in neighborhoods and camps purchased weapons and organized in what were locally called “self-defense groups.” Following the signing of the Juba Peace Agreement in 2020, Massalit fighters organized in the newly formed Sudanese Alliance, an armed group led by Khamis Abbakar, who later became governor in June 2021. The group steadily recruited and trained within the Massalit community until the start of the conflict in 2023.

The appointment of Mohamed Abdalla al-Doma, a Massalit man and Abbakar’s predecessor, as governor in 2020 had heightened tensions with Arab communities. Representatives of Arab tribes in early 2021 held a sit-in demanding the removal of camps of displaced persons from the city and the appointment of a non-Massalit governor. They also demanded that the RSF, which disproportionately recruited from among Darfuri Arabs, be deployed in El Geneina to provide security in lieu of the police, in which Massalit people were more represented. With the ethnic cleansing campaign of 2023, much of this agenda was accomplished.

The crimes committed against the Massalit since April 2023 have not been restricted to El Geneina. At least seven towns and villages of West Darfur have been deliberately destroyed by fire since mid-April 2023. On May 28, 2023, while the assault on El Geneina was underway, the Rapid Support Forces and allied militias attacked the predominantly Massalit town of Misterei, killed and injured dozens of civilians, including at least 28 ethnic Massalit men who were executed, and destroyed the town.

The response of actors from the regional and international community to the unfolding atrocities has been muted, in line with their lackluster engagement on Darfur and Sudan in recent years. Since April 2023, these actors were repeatedly warned, including by the UN Panel of Experts, about events unfolding in West Darfur, and, instead of expanding the scope of UN engagement, many failed to even condemn the violations of an existing arms embargo on the region, let alone act to prevent further atrocities. Actions to punish and deter arms embargo violations by the UN Security Council were nonexistent, and any positive developments were few and far between.

In July 2023 the office of the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC) said it was opening investigations into recent abuses in Darfur as part of its broader mandate in the region, stemming from a UN Security Council referral in 2005. In October, the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva established an Independent International Fact-Finding Mission (FFM) for the Sudan, but its investigations were significantly delayed by a liquidity crisis at the UN, at time of writing.

The humanitarian response in Chad has been woefully underfunded and struggled to provide adequate basic support for the tremendous needs of a massive population that has suffered such extreme violence. Over 88 percent of the refugees are women and children; most have received paltry humanitarian support to date.

The UN and the AU, in consultation with the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), should deploy a new mission to Darfur with a strong policing component, mandated to protect civilians, monitor human rights and humanitarian law violations, and lay the groundwork for the safe returns of those displaced. The UN Security Council should immediately roll out targeted sanctions against those most responsible for the heinous crimes documented in this report, including against Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo “Hemedti,” Gen. Abdel Raheem Hamdan Dagalo, Gen. Abdel Rahman Joma’a Barakallah, Musa Angir, Amir Massar Abdelrahman Assil, and Amir Hafiz Hassan. It should also sanction individuals and entities violating the arms embargo on Darfur. The UN Human Rights Council should ensure the FFM for Sudan is able to carry out necessary investigations, extending and renewing its mandate as necessary, and UN leadership and member states should ensure the FFM has the resources to carry out its work. States should also cooperate fully with the ICC’s investigations, and the court’s member states should ensure it has the robust financial resources necessary to support work across its docket, including in Sudan. All of these efforts should work with survivors when formulating accountability, reparations and justice responses.

Concerned governments and international and regional institutions, including the European Union (EU), Kenya, and the United States, should insist that communities from Darfur be represented in ongoing political processes. Donors should fund initiatives undertaken by Sudanese rights organizations to document ongoing crimes, including specialists in women’s rights. EU member states, the US, Canada, and others should increase refugee resettlement from neighboring countries for refugees who remain at high risk and cannot return to Sudan. Donors should also significantly increase humanitarian assistance for the Sudan humanitarian response, including by increasing assistance to local aid actors.

4 notes

·

View notes