#the napoleonic wars: a global history

Text

“Overall, Napoleon did succeed in unifying these diverse regions into just three polities—‘French Italy’ in the northwest, the Kingdom of Italy in the northeast, and the Kingdom of Naples in the south—that featured uniform legal, administrative, and financial structures modeled on the French system. […] For the first time since the fall of the Roman Empire, the Italian peninsula, with its great diversity of spoken languages (as many as twenty different dialects), customs barriers, differing legal systems, currencies, and systems of weights and measures, came under control of a centralizing and standardizing authority.”

— Alexander Mikaberidze, The Napoleonic Wars: A Global History

#Alexander Mikaberidze#Mikaberidze#The Napoleonic Wars: A Global History#Italy#kingdom of Italy#kingdom of Naples#Naples#napoleonic era#napoleonic#napoleon bonaparte#napoleon#italian history#history#french revolution#first french empire#french empire#france#french history#reforms#napoleonic reforms#Napoleon’s reforms

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am once again begging Hallmark to provide some of the alternate-history worldbuilding behind the fake nations in their royalty romances.

I caught a piece of one last week where the guy tells the main girl, "I'm a prince from St. Ives. It's a tiny monarchy just off the coast of the UK."

On the one hand, kudos for actually explaining why their royals are extremely British. On the other hand, how on Earth did they manage that? You're telling me you've managed to maintain an independent monarchy just off the coast of one of the great European naval powers? That somehow, across centuries, the nation that subdued every other competing nation on their island couldn't spare an afternoon to come conquer you? St. Ives is ruled by a king, not a duke or a prince, so it's not like they're a vassal micronation. One of the great global-spanning empires was somehow okay with letting an entirely different monarchy rule a teeny-tiny island that was sitting right on their doorstep. How did that happen??

It gets even more complicated when the girl goes to the royal palace in St. Ives. Her boyfriend tells her she's being put into "the Wellington Suite." Are you implying that Duke of Wellington is a St. Ives title? Is the entire history of the Napoleonic Wars different in this world? Stop telling me about the girl's personal shopper and start telling me about how this nation has altered European history! Explain, Hallmark!!

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

At the heart of every work of speculative fiction is a “what if,” a divergence which demarcates the line between worlds: what if aliens made contact with us? What if we suddenly had access to supernatural powers? The heart of Manorpunk 2069 is this: “what if it just keeps going like this?”

It is the most difficult question of all, because things quite clearly cannot keep going on like this, and my bravery in tackling this question directly shows why all other spec fic authors besides me are cowards, and probably reactionary.

That was a joke. Spec fic authors are not automatically reactionary. Authors of alternate history fiction definitely are, though. “Ohhhh what if the South won the American Civil War” oh you mean what if the Southern planter class survived and continued to enforce a program of white supremacy and oppression? Why I can hardly imagine such a world.

That was also a joke. My apologies. I am speaking to you as Manorpunk’s figurative father, and being a first-time dad, I cannot help being mawkish and overwrought, showing off baby pictures and trying to guess whether the audience is overcome with a new depth of emotion or simply trying to stifle a yawn.

In any case, I am here to give you the short version:

A series of crises known uncreatively as the Polycrisis struck America in the 2030s: climate change-fueled natural disasters, crumbling infrastructure, the final hollowing-out of the federal government, and the biggest goddamn real estate crash you’ve ever seen.

You can argue whether the real estate crash was the ‘biggest’ or ‘most important’ of the Polycrisis’s constituent parts, but in any case, it was the kicking-in of the rotten door that was America’s economy, and things just kinda… stopped working. Power became decentralized and regionalized, first to whoever could guarantee basic services and infrastructure (because neither the federal government or corporate finance sector had any will or ability to do so), soon coalescing into a half-dozen or so regional power blocks.

Oh, there were a couple more failed wars. Well, just one, really. There were the “IMF Wars” from 2035 to 2037, where the IMF and World Bank were forcibly removed from sub-Saharan Africa by “Chinese-supported Sankarist rebels,” which is how America referred to a democratically-elected government, but that wasn’t really a war-war.

China did give them a fuckton of support though, by the by. The 2030s looked like a hopeful time for the global south, as America fell apart and China hadn’t swallowed the world whole yet.

Speaking of which - at this point you may be asking yourself, “but where is the contingency? Where is the Innocent? Where is our Caesar, our Napoleon, our great Hegelian figure who holds the moment in his hand like a fly trapped in amber?”

Turns out it was Xi Jinping.

Yeah. Sorry.

As you might imagine, China was getting pretty sick of America dicking around. The American economy was collapsing so furiously that it was starting to threaten the export market for Chinese manufacturing. And, y’know, there was the Taiwan War.

Shit, right, the Taiwan War. It was hardly a war - China sank a couple US vessels, the US realized they had fallen too far behind on military tech and tactics, war’s over. The real fight, everyone knew, would be at the bargaining table.

What happened next goes by many names - the Great Bailout, The Reverse Marshall Plan, America’s Bride Price, The Gweilo Divergence, and “using the barbarians to control the barbarians” - a reference to the Self-Strengthening Movement of the Qing Dynasty. That one’s a thinker.

Anyway, China basically bought America. Second Cold War: over, winner: China, victory: flawless. As a fun footnote, the Great Bailout was finalized on September 4, 2039 - the 200th anniversary of the First Opium War.

It was more complicated than that, obviously - it was a tangled mess of playing musical chairs with corporate boards, merging and splitting and shuffling around. A controlled flood of investor money. The tactics were similar to how they had taken - right, I almost forgot, Russia was basically a Chinese protectorate at this point, and China did a similar economic shuffle to Russia after the Russo-Ukraine War.

Anyway! Short version, the timeline has made it to the 2040s and China just sort of swallowed the world whole. Tune in next time to see how that goes!

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

On 27 April 2024 at 00:56 UK time, Sedna enters Gemini. It was there before - 15 June 2023 to 22 November 2023. Fun fact - Pluto left Aquarius on 11 June, retrograding back into Capricorn. So Sedna pretty much immediately took up its watch as a planet of transformation sitting in an Air sign. It stayed there till retrograding back into Taurus on 22 November. This time when Sedna goes in it’s there full time till 2065. 2023 - a transformative year for AI - took place with Pluto and Sedna in Air signs. With both of them in air signs and regularly trining each other through to 2025, we have some technological and innovative energy in the astrological weather.

Sedna has an 11,400 year cycle - it is the furthest object from the Sun that we know of that has any real significance in terms of size. This makes it the slowest dwarf planet we have to work with. But right now, it’s like Pluto - the warm, nearby, fast Kuiper Belt Dwarf Planet. It can go through a zodiac sign in decades, not centuries.

How can that be? Sedna has an incredibly irregular orbit. It skirts the Oort clous and interstellar space then comes into the Kuiper belt. Here’s the dates when Sedna entered various signs:

Scorpio: pre-3000 BC

Sagittarius: 1441 BC

Capricorn: 24 BC

Aquarius: 1047

Pisces: 1633

Aries: 1864

Taurus: 1966

Gemini: 2023

Cancer: 2065

Sedna will reach its closest point to the Sun on 16 July 2076 at 7°54 of Cancer. Since December 1980 Sedna has been so close to us that it’s relegated Eris to being the most distant of the dwarf planets. This is a rare situation caused by Sedna being as close as it comes to us while Eris is as distant as it ever gets. This rare, very specific occurrence will last for the entire 21st century.

What does it mean to live in a strange time when the Erisian energy - which is martian and plutonian and associated with core truths and transformations, is slower and more distant than the evolutionary energies of Sedna? It feels appropriate for a time when we are learning to accept people’s core, immutable truths (queerness, neurodiversity, formative experiences, etc) but concepts like transhumanism and AI and climate change make our position in evolutionary history feel pretty shaky and mutable.

So, Sedna’s time in Gemini is astrologically unprecedented, at least in terms of how it impacts humans. But unprecedented does not mean significant. Sedna may be the farthest astrologically significant object that we know of - but we don’t know what else is out there. But there’s a few things that intrigue me about Sedna in Gemini

The Pluto Trines

The Pluto-Sedna trine will be exact in July 2024, December 2024, August 2025 and November 2025 but it has been within 3 degrees from 2020-2028. This current Pluto-Sedna cycle started with a conjunction in April 1814 as Napoleon was getting exiled. The last trine was active in 1951-1958. One interpretation of this is a spiritual crisis. I’m wondering about facing the concept of extinction in some form or other. When Pluto and Sedna were in fire signs we had a Cold War and nuclear weapons coming in. In Earth signs we had “nature is healing, we are the virus” and now we have people worrying about AI under air signs. But there’s an underlying fear from way back in 1814 - global war. It’ll be interesting to see how this one feels.

The Jupiter Conjunctions

On 27 May 2024, Jupiter conjuncts Sedna for the first time in Gemini just 31 days after Sedna enters the sign and brings its luck, confidence and over-exaggerations into the area of communications and innovation. It’s hard to get away from this being a good sign for techno-optimists. Sedna is in Gemini for 44 years and manages to fit in 4 conjunctions with Jupiter. This is the maximum number of Sedna-Jupiter Conjunctions you can fit into this time.

Of course this is good for tech at first, but it has another side. Each conjunction is the start of a cycle where Jupiter raises the question of the evolutionary issues Sedna raises. This is a long time for us to fail, try again, and fail better.

The Saturn Conjunctions

In 2030 and 2061. 2030 is too far away to predict what this will mean but I think it’s worth noting that once again, Sedna in Gemini fits in the maximum number of cycles - two Sedna-Saturn cycles maybe raising questions on the limits of communication, innovation, sociability, development, and all those airy cyberpunk things that seem to be likely in our future.

The Uranus Conjunction

On 24 May 2026 Uranus will complete a conjunction with Sedna at 1°37 of Gemini. That’s pretty early in the Sedna-Gemini era. Uranus has an orbital period of 84 years so there’s no necessity we were going to get a Sedna-Uranus conjunction in Gemini at all. You’re hopefully getting a picture here. The Solar System has four gas giants and four gas giants conjunct Sedna in Gemini. All of them have the maximum number of conjunctions possible in Gemini. Not only that, but we have Jupiter, Pluto, and Uranus making important aspects to Sedna early on in the Sedna in Gemini era. Sedna is really punching above its weight this week.

The Neptune Conjunction

Neptune’s conjunction with Sedna will come on 2064-2065 in the last degree of Gemini. I find this fascinating. Sedna starts off in Gemini with a series of important conjunctions with slow moving major planets. Then, as it’s about to leave, it has another important conjunction. Sedna is Gemini has a lot to do.

If we accept that Sedna is raising our awareness of evolutionary issues and increasing our ability to see into deep time and beyond usual concerns, this makes Sedna an important factor in the coming decades. In Gemini, we could expect these questions to be to do with how we think, communicate, generate information and network. These aren’t small issues at the moment so I feel this makes perfect sense.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Naomi Novik Has Never Written a Bad Book in Her Life. Let's Talk Temeraire.

*THIS POST HAS SPOILERS. BE WARNED*

I think at this point, it's very, very clear that in this blog, we stan Naomi Novik--and the personal and professional levels of jealousy that she has never written a bad book in her life are real, but do not stop us from celebrating the absolute majesty that is the Temeraire books. If you love a good ensemble cast, then I promise you that the ensemble that Novik builds in these nine books exceeds any other. Yes, even that one. *ducks literally every ensemble fandom yeeting things at my head*

For anyone who hasn't encountered these books before, the tagline is basically "A Napoleonic Wars Travelogue With Dragons," but that does not do justice to the geopolitical, interpersonal, and institutional tour de force that are the different threads of this series. I'll try to avoid mega spoilers, but I'm talking about an entire series, so tread with caution. There MAY BE SPOILERS here.

I belive I was an undergrad when I first discovered this series--as you can perhaps tell from the very, very loved trade paperback copy of His Majesty's Dragon. This first book opens with Captain William Laurence, rising star in his majesty's navy, beating the tar out of a French man-of-war. Except whoops, there is a dragon egg on board, and most inopportunely, it's about to hatch. The aerial corp is...looked down on at best at this point in Novik's alternate fantasy history, and having to harness a dragon means the complete and utter destruction of a naval officer's career. When Temeraire hatches, Laurence ends up harnessing him while trying extremely hard not to think about what he's doing and what the implications for his personal and professional life will be.

This first book is very much all about Temeraire and Laurence finding their footing in the aerial corps and with each other. Laurence has to learn to let the navy go, and yet is in the unenviable position of being just enough of an outsider int he aerial corps to question things the other aviators take for granted. This is gonna be a theme.

Then there is Temeraire. It's easy, so so easy, to forget how young Temeraire is throughout this series. He's just a baby, really, in this book, but is nevertheless yeeted into the Napoleonic wars, where he is entirely unafraid to demand both fair treatment and answers to questions. This will also become a theme.

We also meet the formation of dragons and captains in this book that we will follow throughout the rest of the series, and the sheer amount of personality Novik packs into them makes this world and ensemble absolutely rich. There are--thankfully--not as many named characters in these books as there are in The Wheel of Time or Game of Thrones, but in many ways, these captains and dragons are more fully human the secondary characters in those worlds. *ducks the WoT and Jordan fans' rage*

His Majesty's Dragon is the smallest scale book of the series, and really spends time immersing you in the covert and the aerial corps. This is the smallest the world ever feels in the series, and it doesn't feel small.

The world and dragon lore expand rapidly in Throne of Jade, which is unequivocally my favorite book in the series, despite my favorite dragon of the series not appearing in it. This book's catalyst is the consequences of Naval Captain William Laurence defeating a French ship and taking a Chinese dragon egg--which turned out to be a Celestial, or Lung Tien--as a prize. Turns out, the Emperor of China and his former heir don't love that Temeraire was not only harnessed but also subjected to the brutalities of war. In China, Celestials are first and foremost scholars. Oh, and China and England have diametrically opposed philosophies on dragons as indidivuals and their rights. So in chapter one of this book, we are already dealing with global politics, philosophies of personhood, civil rights (or lack thereof) for dragons, and themes of nationalism, imperialism, colonialism, and isolationism. And that's just the plot.

Interpersonally, we have Temeraire learning to live with both his love for and partnership with Laurence and the heritage and birthright that would offer him an education, civil rights, rank, and possibly the chance to make real changes to how his friends and colleagues in England are treated. Mix that with Laurence, who has the curse of having an open enough mind to be a realistic match for Temeriare's exuberance and idealism and who is dealing with turning his entire life on its head for the second time in less than two years. Then, just to twist the knife, Novik gives us an entire angsty subplot about Laurence freeling giving Temeraire the choice to stay in China, and having to decide if he will stay or not, in the face of massive personal and political pressures. You guys, I love this book so much.

We also meet Lung Tien Lien in this book, and y'all need to remember that name, because this albino Celestial--considered bad luck in China--defects to Napoleon after her companion is killed and that has ramifications through to the final book in the series. Lien and Temeraire honestly do not get along, although this book sees Laurence collect the first two of what will become a freaking rolodex of international connections. De Guinges, the French ambassador to China, has an absolutely delightful amicable sparring relationship with Laurence, and he pops up throughout the series like that dickhead friend who is fantastic for a night out, but would grate if he stuck around much longer than that. The other connection is Prince Mianning, who becomes Laurence's brother when the Emperor adopts Laurence to sever a political Gordian knot. That's also going to have some ramifications down the road.

Black Powder War is essentially the consequences of Laurence's decision to haul ass to Istanbul via a land route to take custody of three dragon eggs England has purchased from the Ottoman Empire. For the geographically savvy of you, yes, this means a desert trek. It also means a guide, who is rapidly but reluctantly added to Laurence's rolodex of connections: Tenzing Tharkey. Tharkey is in and of himself absolutely freaking fascinating--he could be his own post. The son of an English officer and a Nepali woman who was educated but literally always on the margins of every society he interacted with, Tharkey is savvy about basically everything, and SUS AF in this book. I'm going to put a pin in this, however, because Tharkey will absolutely return in the series and literally never fail to be a complete BAMF.

Generally speaking, Black Powder War is my least favorite of the series. It's by no means a bad book, and we meet characters who become crucial and some of my favorites, but the desert trek and brief stay in Istanbul are the bits of the book I tend to forget because with the exception of the introductions of Tharkey, Arkady, and Dragon Queen of the Series Iskierka, it doesn't have the lasting consequences that their time in Austria in the latter sections of the book does.

Prussian dragon treatment is--it's rough, you guys. And the fact that Temeraire and Laurence STILL end up single-handedly evacuating the Prussian royal family and the entire garrison at Danzig as Napoleon's army is literally banging at the fort door and the book ends as a fully-loaded Temeraire is hauling ass into the sky as the defeat turns into a rout means that the last third of the book is the most memorable.

Empire of Ivory picks right up on that frantic flight from Austria, and they make it back to England where Laurence is rightfully furious that their screams for help on their horrifically dangerous aerial channel crossing went entirely unanswered. Poor Temeraire is too exhausted to be anything more than confused as to why his friends didn't come when he called. The heartbreaking truth? There was no one to send.

Ladies and gentlemen, we have ourselves a plague book.

Let me back up for a second. In Throne of Jade, Temeraire briefly runs into his formation, and they're all a bit coldy. Temeraire catches the cold too, but is dosed with a mushroom acquired by the dragon doctor as they passed Africa on the way to China. Temeraire recovers, and literally nobody thinks twice about getting a cold on the long journey to China. It's a ship, people get colds.

It's only once Temeraire and Laurence return home that the trifling cold has turned into a wasting disease that the aerial corps has no way to cure and really no way to treat. Once the dragon surgeons get together and theorize that whatever that mushroom Temeraire ate was a cure, Temeraire and his entire formation are loaded onto a dragon transport with their captains and crews to find the cure. This bit is genuinely heartbreaking guys, because the entire vibe of Maximus getting on the ship is that they either find a cure or they bury him in Africa. Berkeley so desperately needs a hug for like two thirds of this book.

This is quite possibly my favorite book after Throne of Jade, because I am here for a good plague book--and I know that might be a weird take in the year of our lord 2022--but especially a good plague book that shoves English officers' noses in the consequences of colonialism and the slave trade and actually includes the yeeting of slavers and colonizers from their settlements with the help of Kefentse and the other dragons. Seriously, this book is SO GOOD.

The best part of it though, is the last couple of chapters. Laurence, Temeraire, and co. make it back to England with the cure only to find that England has sent a plague carrier into France to infect Napoleon's aerial corps. Laurence--and the crucial thing is that this is Laurence's idea, from start to finish, he wasn't prompted by Temeraire--commits full-on bald-faced treason by taking a tub of cultivated mushrooms to Napoleon himself. An entirely floored but immensely grateful Napoleon offers Laurence and Temeraire asylum in France, but the final chapter of the book is Laurence and Temeraire taking a quiet moment before they cross the channel back to England to face the music. Y'all, I cried so hard finishing this book. I was just grateful that I caught the series at a point where I didn't have to wait a year or more to read the next book.

Victory of Eagles, of all the books in this series, is for the dragons. Laurence is so deep in self-loathing and probably actual depression that he briefly ends up as Wellington's personal dirty job doer, which just exacerbates the problem, because what Laurence is truly deeply wrestling with is the clash between his honor and the whole "I would do treason again because it was the right thing to do" thing.

We spend most of this book with Temeraire though, as he single-handedly empties the breeding grounds of dragons and wrangles them into a massively effective army. He then proceeds to strong arm Wellington into paying the dragons, feeding them, and granting them civil rights. It's not a perfect system by any means, and it's deeply influenced by the Chinese perspective on dragons, so it's a hard sell for Temeraire, but he pulls it off. The other thing Temeraire pulls off is showing Laurence that he can reconcile seeming oppositional worldviews and come to an equilibrium with himself. It's messy as hell, and you bet your ass it has consequences, but this is a real turning point in Laurence and Temeraire's relationship, and their own personal journeys. This book is absurdly well executed.

The consequences of Laurence reconciling his honor and personal philosophy are explored in Tongues of Serpents or Laurence and Temeraire Take Australia or Iskierka Wants an Egg From Temeraire and Really Can't Believe Everyone Isn't Automatically on Board. This is another book for the dragons, really. We get to meet Caesar and Kulingile, and if y'all thought Maximus was the ultimate dragon himbo, my big regal copper baby is about to get dethroned by our Cheequered Nettle/Parnassian hybrid. Regal Coppers in general have himbo vibes, but they're also adorably grouchy old men. Kulingile is basically Kronk in dragon form, with none of the grumpy old man that Regal Coppers have.

What kills me about this book is that Laurence was *THAT CLOSE* to successfully breaking up a smuggling ring and disappearing into the outback for a quiet retirement with Temeraire on their own land in Australia, where they could be left alone and happy.

Then Crucible of Gold starts. Arthur Hammond, who Laurence added to his rolodex way back in Throne of Jade, shows up to Laurence's half-built dragon pavilion and house in the Australian outback to drag him back into global politics. Laurence was *SO CLOSE* to being left alone. He had a BEARD, for crying out loud. He was HAPPY. He and Temeraire were building something. But Hammond manages to talk them into running off to Brazil--by way of a shipwreck and psuedo rescue by the French and a subsequent marooning--to stop them from allying with Napoleon. That mission ends up being a hideous failure because of a combination of the consequences of colonialism, Iskierka being an objectively terrible matchmaker, and Napoleon showing up to put a ring on it.

And to top off the whole ill-fated mission, Gong Su, Laurence's trusted cook, turns out to be working for Prince Mianning, which Hammond wastes zero time leveraging to drag Laurence and Temeraire back to China.

Before we manage to get back to China, however, Blood of Tyrants opens with another shipwreck and Laurence waking up in Japan missing about eight years of memory. And guys, let me tell you, watching Naval Captain William Laurence get suuuuuuuuuper traumatized by everything aerial corps Captain Laurence has done is both hilarious and heartwrenching. The other captains in the formation literally have a "do we tell him about the treason?" conversation that is just on point. And in the background of all of this, Iskierka finally gets the egg she has been frankly harassing Temeraire for for the last like three books. So they're dealing with Laurence/Temeraire drama, geopolitical drama, and Iskierka egg drama.

At that point, finally getting to China and uncovering a false-flag rebellion orchestrated by the conservative party to smuggle just *so much* opium and discredit Mianning felt pretty darn straightforward. Then it all got complicated again, because somewhere along the line, 300 Chinese dragons were promised to support the Russians against Napoleon, and Laurence and Temeraire end this book literally trying to stop Napoleon from conquering Russia in winter. None of this is actually *good* for the character, but I was hanging on each setback and just going "WHAT HAPPENS THEN?"

Well, what happens next in League of Dragons is that Laurence does the most emotionally constipated British Officer thing I have EVER seen and challenges a Russian officer who had a little too much to drink because both his adopted and biological fathers died in the span of like a month or two, and Laurence cannot deal with feelings that big. That duel goes exactly as well as you'd expect, and both men end up very shot, but they also manage to survive, barely. Then we spend the rest of the book wrapping up the plot threads from the preceding eight books, and watching Iskierka and Temeraire realize why the two of them making an egg was both the best and worst possible idea.

This series is just supremely well plotted and well executed, and there will never be any other dragons in the world with this much personality.

#naomi novik#temeraire#his majesty's dragon#in his majesty's service#captain william laurence#throne of jade#black powder war#empire of ivory#victory of eagles#tongues of serpents#crucible of gold#blood of tyrants#league of dragons#iskierka#john granby#maximus#berkeley#lily#captain harcourt#jane roland#emily roland#books & libraries#fantasy#fiction#book recommendations#books and reading#dragons#napoleonic wars#napoleonic era#alternate history

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Two world wars have obscured the huge scale and enormous human cost of the Crimean War. Today it seems to us a relatively minor war; it is almost forgotten, like the plaques and gravestones in those churchyards. Even in the countries that took part in it (Russia, Britain, France, Piedmont-Sardinia in Italy and the Ottoman Empire, including those territories that would later make up Romania and Bulgaria) there are not many people today who could say what the Crimean War was all about. But for our ancestors before the First World War the Crimea was the major conflict of the nineteenth century, the most important war of their lifetimes, just as the world wars of the twentieth century are the dominant historical landmarks of our lives.

The losses were immense – at least three-quarters of a million soldiers killed in battle or lost through illness and disease, two-thirds of them Russian. The French lost around 100,000 men, the British a small fraction of that number, about 20,000, because they sent far fewer troops (98,000 British soldiers and sailors were involved in the Crimea compared to 310,000 French). But even so, for a small agricultural community such as Witchampton the loss of five able-bodied men was felt as a heavy blow. In the parishes of Whitegate, Aghada and Farsid in County Cork in Ireland, where the British army recruited heavily, almost one-third of the male population died in the Crimean War.

Nobody has counted the civilian casualties: victims of the shelling; people starved to death in besieged towns; populations devastated by disease spread by the armies; entire communities wiped out in the massacres and organized campaigns of ethnic cleansing that accompanied the fighting in the Caucasus, the Balkans and the Crimea. This was the first ‘total war’, a nineteenth-century version of the wars of our own age, involving civilians and humanitarian crises.

It was also the earliest example of a truly modern war – fought with new industrial technologies, modern rifles, steamships and railways, novel forms of logistics and communication like the telegraph, important innovations in military medicine, and war reporters and photographers directly on the scene. Yet at the same time it was the last war to be conducted by the old codes of chivalry, with ‘parliamentaries’ and truces in the fighting to clear the dead and wounded from the killing fields. The early battles in the Crimea, on the River Alma and at Balaklava, where the famous Charge of the Light Brigade took place, were not so very different from the sort of fighting that went on during the Napoleonic Wars. Yet the siege of Sevastopol, the longest and most crucial phase of the Crimean War, was a precursor of the industrialized trench warfare of 1914–18. During the eleven and a half months of the siege, 120 kilometres of trenches were dug by the Russians, the British and the French; 150 million gunshots and 5 million bombs and shells of various calibre were exchanged between the two sides.

The name of the Crimean War does not reflect its global scale and huge significance for Europe, Russia and that area of the world – stretching from the Balkans to Jerusalem, from Constantinople to the Caucasus – that came to be defined by the Eastern Question, the great international problem posed by the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire. Perhaps it would be better to adopt the Russian name for the Crimean War, the ‘Eastern War’ (Vostochnaia voina), which at least has the merit of connecting it to the Eastern Question, or even the ‘Turco-Russian War’, the name for it in many Turkish sources, which places it in the longer-term historical context of centuries of warfare between the Russians and the Ottomans, although this omits the crucial factor of Western intervention in the war.”

- Orlando Figes, introduction to The Crimean War: A History

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Russophobia has always been present in the political West. Whether it’s simply the fear of a near-peer adversary or perhaps the age-old sea power (thalassocracy) vs. a land power (tellurocracy) competition, the fact is that the belligerent power pole really does not like Russia, to put it mildly. Moscow has been trying to find common ground with the political West for centuries. However, that seems all but impossible, as the latter stubbornly refuses to engage with the Eurasian giant. It can even be argued that this has been the defining characteristic of European and global geopolitics, pushing the “old continent” and the world into several destructive conflicts. Interestingly, the leading Western power, the United States, doesn’t really have a long history of Russophobia, unlike many European countries.

After WWII and the advent of the (First) Cold War, the enmity between America and Russia became the standard in the global geopolitical arena. And yet, even then, a level of mutual respect existed, while international treaties were largely respected and played a significant role in keeping the balance of power relatively intact. The unfortunate dismantling of the Soviet Union put an end to this, especially after neocons and Atlanticists took power in Washington DC. However, of all US allies, vassals and satellite states, there’s one that makes even such endemically Russophobic countries like Poland or the Baltic states seem “moderate enough” – the United Kingdom. London’s Russophobia is so deeply ingrained in its geopolitical strategy, even when it was officially allied to Moscow, both during the Napoleonic and World Wars.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

this is only tangentially related to fl, but ive been thinking a lot about the genre of historical fiction where nobody is prejudiced ever (or if they are, it's in ways that aren't real, like being prejudiced against rubberies but not people of color, or are no longer relevant, like people in fl still being anti-catholic but not antisemitic. as far as we know anyway)

it's... interesting. it definitely has its pros, and i see why people would want to craft that kind of world to play in, but i also think it's worth acknowledging the downsides, too. also this post is really long but i couldn't find a good place to stick a readmore. look at my posts, boy

like, i get that nobody wants to write Period Accurate Racism Simulator, both for personal moral reasons (ie "I don't want to write racist texts") and for commercial reasons ("No person of color is going to want to buy Period Accurate Racism Simulator") but also... so much of society is structured around prejudice that historical stuff almost falls apart without it

i was in two Regency-era larps, and both of them were "no prejudice" alt history, one of which had a whole alternate timeline explaining why Britain was a global superpower even though colonialism didn't happen, and the other one... well never quite got around to explaining the worldbuilding. but both were in agreement that Queen Elizabeth I ended sexism forever (and also homophobia and transphobia i guess??)

but like... so much about what is iconic about the regency era (especially in regency romances) is the negotiation with extremely strict social rules, which were, at their core, about controlling women. a woman can't be alone with a man because that's improper! i mean... what if they fuck each other???? But if it's equally valid for this woman to be in a relationship with another woman, then... it would also be improper for her to be alone with other women? okay so she can't ever be alone... but if polyamory is a possibility, then i guess she can't be in groups, either, because they still might all fuck each other!!! so nobody can... ever be around anybody? of course, if we dont view a woman's assumed reproductive capability as a commodity that must be protected and secured, then we don't need to police who she is alone with, but then we remove the stuff that's fun and interesting about Regency romances! At this point, we're just writing regular fiction, but everyone's dresses are really high waisted.

And I mean, if we imagine a Regency era Britain where colonialism flat out did not happen... how are any of these characters this wealthy? How are they still using the products that were made accessible to Britain because of colonialism, like fabrics from India? If there were no colonies, then Britain didn't colonize North America, then there was no Revolutionary War, which means France didn't go into debt FUNDUNG the Revolutionary War, which means it wasn't in the dire financial straits that lead to the French Revolution, which means that Napoleon would not rise to power because of his military service DURING the French Revolution, which means the Napoleonic Wars aren't going to happen, but obviously we're still having the Napoleonic Wars because how are you gonna do Regency Era without its tentpole features, like people achieving upward mobility through exceptional military service against the dreaded Napoleon. And don't even get me started on how the history of Corsica would fit into all this!!!

People made the decisions they made because of the world they lived in, and if you change fundamental aspects of the world they lived in, its absurd to have them make the same decisions.

And on top of that, it actually ends up being kind of limiting for what kinds of stories you can tell. i mean, if no prejudice exists, then you can't have anyone interacting with it, internalizing it, or overcoming it. To have a character that, for example, is concerned about homophobia would be as bizarre in this setting as someone worrying about societal backlash because... idk their favorite color is red instead of blue. Who cares! Do you care? Clap if you care.

I know that's the fantasy some people like engaging with, and that's perfectly fine, but... well, it's not what I like writing.

I think Fallen London splits the difference pretty well- society still exists on the Surface as it always has (more or less), so you can still write characters engaging with it, but having London be it's own little pocket of equality has its own problems. I mean, if London was moved underground and the Masters granted everyone equal rights under the law, then that means no minority has ever campaigned for an expansion of their own rights and succeeded. There was no real Women's Sufferage movement in London, because there was no need. But there were Suffragettes who did cool stuff!! Stuff that might be interesting to engage with, but you can't, because of the setting. You have to overlook the accomplishments of real marginalized people, because the very premise of your story depends on the new government just... deciding to be nice.

Is this a problem that needs fixing? Nah, I don't think so. I think it was good when FBG went to remove some of the #problematic bits of text that still hung around (like changing the description of the Fourth City Airag so it's less... shitty, for example) because that doesn't fit with the tone they're setting. But I think it's fun and interesting to look at the opportunity costs of these decisions!!! im just having fun lol

#long post#one time i was talking to my partner abt how my idea of a good time is taking media apart on my autopsy table to see how they work#and they thought i said my autism table#which is#.... also true#taking fl apart on my autism table because i know how to party

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

The British Empire was, in many ways, a force for good.

Nearly everywhere it occupied it:

-raised the standard of living

-developed infrastructure

-promoted education

It also single-handedly ended slavery for much of the world…🧵(thread) pic.twitter.com/hVNQIIu9Rg

— ThinkingWest (@thinkingwest) May 24, 2024

Though Britain had been a global power since the early 17th century, it wasn’t until Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo in 1815 that it emerged as the dominant power.

By eliminating France from the world’s stage, Britain was left without a serious competitor.

The Vienna Treaty that followed favored the Brits, granting them territorial possessions like modern-day South Africa, Trinidad, and Sri Lanka.

These territories served as strategic naval bases Britain used to control its immense empire from all corners of the globe.

The century following Napoleon's defeat is sometimes called the “Pax Britannica,” because of the relative prosperity enjoyed by Europe during this time. The presence of a single world power created stability and kept conflicts to a minimum.

Britain’s unmatched navy is what maintained its dominance.

The British Royal Navy was more than twice the size of the next largest navy. Though their ships weren’t vastly superior to others’, their sailors were at sea continuously making them the best in the world.

British ships controlled most of the key trade routes in Asia, North America, and Africa, allowing its merchants and traders an overwhelming advantage compared to other nations—Britain got incredibly rich off sea power.

But Britain didn’t just use its Naval supremacy to fill its coffers. Its navy actually became a source of peace and stability.

British ships were on the frontline during one of the darkest episodes in Western history: the slave trade.

Decades before the American Civil War and 13th amendment ended slavery in the US, Britain passed two anti-slavery laws: the “Slave Trade Act 1807” banning the slave trade around the empire, and the “Slavery Abolition Act 1833” which officially made it illegal to own slaves.

Britain enforced its legislation via their strong navy.

Ship captains who were caught transporting slaves were subject to fine initially, but soon the Royal Navy declared all perpetrators of slave trading to be treated the same as pirates—the punishment for piracy was death.

Britain's ships were the “global policemen” in the 19th century, and along the West coast of Africa became highly successful in capturing slave ships and freeing slaves.

They basically declared war on the African slave trade in a move called the “blockade of Africa.”

In 1808, a fleet called the West Africa Squadron was formed to patrol the African coast and catch slave ships. In the following decades they seized an estimated 1,600 slave ships and freed a whopping 150,000 Africans slaves.

African kingdoms were also encouraged to sign anti-slavery treaties. Over 50 African rulers signed them, and for ones that didn't, “corrective action” was taken—sometimes fighting slavery meant using the full force of the British Navy.

One example was the deposition of Oba Kosoko of Lagos in 1851.

After refusing to sign an anti-slavery treaty, the HMS Bloodhound and HMS Tartar besieged Lagos and deposed Kosoko. He was quickly replaced with an anti-slavery rival named Akitoye.

While some illegal trade continued in far-off regions, by the middle of the 19th-century the Atlantic slave trade was almost completely eradicated.

Slavery outside the empire’s jurisdiction, however, would continue for hundreds of years in some places.

No nation on earth did more to eliminate slavery than Britain.

Though empires are often viewed as inherently tyrannical, Britain’s war on slavery shows that immense power can, in some cases, be channeled for good.

Undoubtedly some terrible things were done under its rule, but Britain's success against slavery leaves one questioning whether empire per se is always a bad thing. Is it possible to have a benevolent empire?

#the british empire#great britain#history#twitter repost#19th century#1800s#victorian#european history#world history#british empire#slavery

1 note

·

View note

Text

Clinging Bitterly to Guns and Religion

By William J. Astore

June 08, 2023: Information Clearing House --All around us things are falling apart. Collectively, Americans are experiencing national and imperial decline. Can America save itself? Is this country, as presently constituted, even worth saving?

For me, that last question is radical indeed. From my early years, I believed deeply in the idea of America. I knew this country wasn’t perfect, of course, not even close. Long before the 1619 Project, I was aware of the “original sin” of slavery and how central it was to our history. I also knew about the genocide of Native Americans. (As a teenager, my favorite movie — and so it remains — was Little Big Man, which pulled no punches when it came to the white man and his insatiably murderous greed.)

Nevertheless, America still promised much, or so I believed in the 1970s and 1980s. Life here was simply better, hands down, than in places like the Soviet Union and Mao Zedong’s China. That’s why we had to “contain” communism — to keep them over there, so they could never invade our country and extinguish our lamp of liberty. And that’s why I joined America’s Cold War military, serving in the Air Force from the presidency of Ronald Reagan to that of George W. Bush and Dick Cheney. And believe me, it proved quite a ride. It taught this retired lieutenant colonel that the sky’s anything but the limit.

Are You Tired Of The Lies And Non-Stop Propaganda?

Get Your FREE Daily Newsletter

No Advertising - No Government Grants - This Is Independent Media

In the end, 20 years in the Air Force led me to turn away from empire, militarism, and nationalism. I found myself seeking instead some antidote to the mainstream media’s celebrations of American exceptionalism and the exaggerated version of victory culture that went with it (long after victory itself was in short supply). I started writing against the empire and its disastrous wars and found likeminded people at TomDispatch — former imperial operatives turned incisive critics like Chalmers Johnson and Andrew Bacevich, along with sharp-eyed journalist Nick Turse and, of course, the irreplaceable Tom Engelhardt, the founder of those “tomgrams” meant to alert America and the world to the dangerous folly of repeated U.S. global military interventions.

But this isn’t a plug for TomDispatch. It’s a plug for freeing your mind as much as possible from the thoroughly militarized matrix that pervades America. That matrix drives imperialism, waste, war, and global instability to the point where, in the context of the conflict in Ukraine, the risk of nuclear Armageddon could imaginably approach that of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. As wars — proxy or otherwise — continue, America’s global network of 750-odd military bases never seems to decline. Despite upcoming cuts to domestic spending, just about no one in Washington imagines Pentagon budgets doing anything but growing, even soaring toward the trillion-dollar level, with militarized programs accounting for 62% of federal discretionary spending in 2023.

Indeed, an engorged Pentagon — its budget for 2024 is expected to rise to $886 billion in the bipartisan debt-ceiling deal reached by President Joe Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy — guarantees one thing: a speedier fall for the American empire. Chalmers Johnson predicted it; Andrew Bacevich analyzed it. The biggest reason is simple enough: incessant, repetitive, disastrous wars and costly preparations for more of the same have been sapping America’s physical and mental reserves, as past wars did the reserves of previous empires throughout history. (Think of the short-lived Napoleonic empire, for example.)

Known as “the arsenal of democracy” during World War II, America has now simply become an arsenal, with a military-industrial-congressional complex intent on forging and feeding wars rather than seeking to starve and stop them. The result: a precipitous decline in the country’s standing globally, while at home Americans pay a steep price of accelerating violence (2023 will easily set a record for mass shootings) and “carnage” (Donald Trump’s word) in a once proud but now much-bloodied “homeland.”

Lessons from History on Imperial Decline

I’m a historian, so please allow me to share a few basic lessons I’ve learned. When I taught World War I to cadets at the Air Force Academy, I would explain how the horrific costs of that war contributed to the collapse of four empires: Czarist Russia, the German Second Reich, the Ottoman empire, and the Austro-Hungarian empire of the Habsburgs. Yet even the “winners,” like the French and British empires, were also weakened by the enormity of what was, above all, a brutal European civil war, even if it spilled over into Africa, Asia, and indeed the Americas.

And yet after that war ended in 1918, peace proved elusive indeed, despite the Treaty of Versailles, among other abortive agreements. There was too much unfinished business, too much belief in the power of militarism, especially in an emergent Third Reich in Germany and in Japan, which had embraced ruthless European military methods to create its own Asiatic sphere of dominance. Scores needed to be settled, so the Germans and Japanese believed, and military offensives were the way to do it.

As a result, civil war in Europe continued with World War II, even as Japan showed that Asiatic powers could similarly embrace and deploy the unwisdom of unchecked militarism and war. The result: 75 million dead and more empires shattered, including Mussolini’s “New Rome,” a “thousand-year” German Reich that barely lasted 12 of them before being utterly destroyed, and an Imperial Japan that was starved, burnt out, and finally nuked. China, devastated by war with Japan, also found itself ripped apart by internal struggles between nationalists and communists.

As with its prequel, even most of the “winners” of World War II emerged in a weakened state. In defeating Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union had lost 25 to 30 million people. Its response was to erect, in Winston Churchill’s phrase, an “Iron Curtain” behind which it could exploit the peoples of Eastern Europe in a militarized empire that ultimately collapsed due to its wars and its own internal divisions. Yet the USSR lasted longer than the post-war French and British empires. France, humiliated by its rapid capitulation to the Germans in 1940, fought to reclaim wealth and glory in “French” Indochina, only to be severely humbled at Dien Bien Phu. Great Britain, exhausted from its victory, quickly lost India, that “jewel” in its imperial crown, and then Egypt in the Suez debacle.

There was, in fact, only one country, one empire, that truly “won” World War II: the United States, which had been the least touched (Pearl Harbor aside) by war and all its horrors. That seemingly never-ending European civil war from 1914 to 1945, along with Japan’s immolation and China’s implosion, left the U.S. virtually unchallenged globally. America emerged from those wars as a superpower precisely because its government had astutely backed the winning side twice, tipping the scales in the process, while paying a relatively low price in blood and treasure compared to allies like the Soviet Union, France, and Britain.

History’s lesson for America’s leaders should have been all too clear: when you wage war long, especially when you devote significant parts of your resources — financial, material, and especially personal — to it, you wage it wrong. Not for nothing is war depicted in the Bible as one of the four horsemen of the apocalypse. France had lost its empire in World War II; it just took later military catastrophes in Algeria and Indochina to make it obvious. That was similarly true of Britain’s humiliations in India, Egypt, and elsewhere, while the Soviet Union, which had lost much of its imperial vigor in that war, would take decades of slow rot and overstretch in places like Afghanistan to implode.

Meanwhile, the United States hummed along, denying it was an empire at all, even as it adopted so many of the trappings of one. In fact, in the wake of the implosion of the Soviet Union in 1991, Washington’s leaders would declare America the exceptional “superpower,” a new and far more enlightened Rome and “the indispensable nation” on planet Earth. In the wake of the 9/11 attacks, its leaders would confidently launch what they termed a Global War on Terror and begin waging wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere, as in the previous century they had in Vietnam. (No learning curve there, it seems.) In the process, its leaders imagined a country that would remain untouched by war’s ravages, which was we now know — or do we? — the height of imperial hubris and folly.

For whether you call it fascism, as with Nazi Germany, communism, as with Stalin’s Soviet Union, or democracy, as with the United States, empires built on dominance achieved through a powerful, expansionist military necessarily become ever more authoritarian, corrupt, and dysfunctional. Ultimately, they are fated to fail. No surprise there, since whatever else such empires may serve, they don’t serve their own people. Their operatives protect themselves at any cost, while attacking efforts at retrenchment or demilitarization as dangerously misguided, if not seditiously disloyal.

That’s why those like Chelsea Manning, Edward Snowden, and Daniel Hale, who shined a light on the empire’s militarized crimes and corruption, found themselves imprisoned, forced into exile, or otherwise silenced. Even foreign journalists like Julian Assange can be caught up in the empire’s dragnet and imprisoned if they dare expose its war crimes. The empire knows how to strike back and will readily betray its own justice system (most notably in the case of Assange), including the hallowed principles of free speech and the press, to do so.

Perhaps he will eventually be freed, likely as not when the empire judges he’s approaching death’s door. His jailing and torture have already served their purpose. Journalists know that to expose America’s bloodied tools of empire brings only harsh punishment, not plush rewards. Best to look away or mince one’s words rather than risk prison — or worse.

Yet you can’t fully hide the reality that this country’s failed wars have added trillions of dollars to its national debt, even as military spending continues to explode in the most wasteful ways imaginable, while the social infrastructure crumbles.

Clinging Bitterly to Guns and Religion

Today, America clings ever more bitterly to guns and religion. If that phrase sounds familiar, it might be because Barack Obama used it in the 2008 presidential campaign to describe the reactionary conservatism of mostly rural voters in Pennsylvania. Disillusioned by politics, betrayed by their putative betters, those voters, claimed the then-presidential candidate, clung to their guns and religion for solace. I lived in rural Pennsylvania at the time and recall a response from a fellow resident who basically agreed with Obama, for what else was there left to cling to in an empire that had abandoned its own rural working-class citizens?

Something similar is true of America writ large today. As an imperial power, we cling bitterly to guns and religion. By “guns,” I mean all the weaponry America’s merchants of death sell to the Pentagon and across the world. Indeed, weaponry is perhaps this country’s most influential global export, devastatingly so. From 2018 to 2022, the U.S. alone accounted for 40% of global arms exports, a figure that’s only risen dramatically with military aid to Ukraine. And by “religion,” I mean a persistent belief in American exceptionalism (despite all evidence to the contrary), which increasingly draws sustenance from a militant Christianity that denies the very spirit of Christ and His teachings.

Yet history appears to confirm that empires, in their dying stages, do exactly that: they exalt violence, continue to pursue war, and insist on their own greatness until their fall can neither be denied nor reversed. It’s a tragic reality that the journalist Chris Hedges has written about with considerable urgency.

The problem suggests its own solution (not that any powerful figure in Washington is likely to pursue it). America must stop clinging bitterly to its guns — and here I don’t even mean the nearly 400 million weapons in private hands in this country, including all those AR-15 semi-automatic rifles. By “guns,” I mean all the militarized trappings of empire, including America’s vast structure of overseas military bases and its staggering commitments to weaponry of all sorts, including world-ending nuclear ones. As for clinging bitterly to religion — and by “religion” I mean the belief in America’s own righteousness, regardless of the millions of people it’s killed globally from the Vietnam era to the present moment — that, too, would have to stop.

History’s lessons can be brutal. Empires rarely die well. After it became an empire, Rome never returned to being a republic and eventually fell to barbarian invasions. The collapse of Germany’s Second Reich bred a third one of greater virulence, even if it was of shorter duration. Only its utter defeat in 1945 finally convinced Germans that God didn’t march with their soldiers into battle.

What will it take to convince Americans to turn their backs on empire and war before it’s too late? When will we conclude that Christ wasn’t joking when He blessed the peacemakers rather than the warmongers?

As an iron curtain descends on a failing American imperial state, one thing we won’t be able to say is that we weren’t warned.

William J. Astore, a retired lieutenant colonel (USAF) and professor of history, is a TomDispatch regular and a senior fellow at the Eisenhower Media Network (EMN), an organization of critical veteran military and national security professionals. His personal substack is Bracing Views.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Letter from Napoleon to his brother, Jérôme. A really interesting letter as I think it clearly displays his unique idealism:

My concern is for the well-being of your people [Westphalians], not only as it affects your standing and my own, but also because of the impact it has on the whole condition of Europe. Do not listen to anyone who says that your subjects, being so long accustomed to servitude, will fail to feel gratitude for the freedoms you bring to them. The common people of Westphalia are more enlightened than such individuals would have you believe, and your rule will never have a secure basis without the people’s complete trust and affection. What the people of Germany impatiently desire is that men without nobility but of genuine ability will have an equal claim upon your favor and advancement, and that every trace of serfdom and feudal privilege... be completely done away with. Let the blessings of the Code Napoleon, open procedures and use of juries be the centerpiece of your administration... I want all your peoples to enjoy liberty, equality, and prosperity alike and to such a degree as no German people has yet known.... Everywhere in Europe—in Germany, France, Italy, Spain—people are longing for equality and liberal government... So govern according to your new constitution. Even if reason and the enlightened ideas of our age did not suffice to justify this call, it still would be a smart policy for anyone in your position—for you will find that the genuine support of the people is a source of strength to you that none of the absolutist monarchs neighboring you will ever have.

Source: Napoleon to Jérôme, November 15, 1807, in Napoleon, Correspondance générale, ed. Thierry Lentz (Paris: Fayard, 2004), VII: 1321.

English translation: Alexander Mikaberidze, The Napoleonic Wars: A Global History

#Napoleon’s correspondence#Napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#The Napoleonic Wars: A Global History#napoleonic era#napoleonic#first french empire#Jerome#jerome bonaparte#Jérôme Bonaparte#Napoleon’s brothers#Napoleon’s reforms#napoleonic reforms#reforms#Westphalia#Germany#1807#1800s#Thierry Lentz#french empire#19th century#letter#letters

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

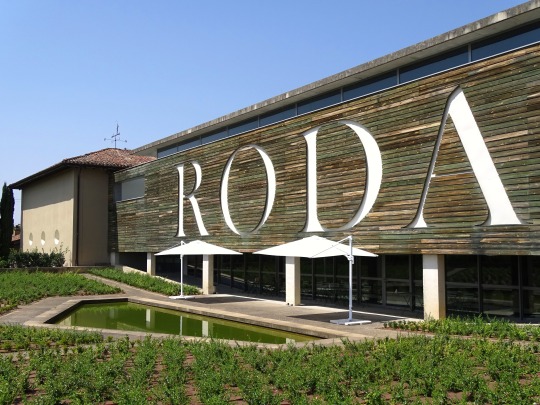

Day of La Rioja

Day of La Rioja is a public holiday in La Rioja, Spain, and is celebrated on June 9 every year. It marks the anniversary of when the autonomous community of La Rioja’s statute was approved in 1982. This beautiful picturesque region is known for its lip-smacking red wine and boasts of over 500 wineries. We firmly believe that there is no such thing as too many wineries but 500 sounds like a good number. The day is celebrated with full vigor in the region by organizing various events including exhibitions of works produced by local artists, traditional and modern music concerts, sports events, and, of course, cooking up some great dishes and washing them down with the world-famous La Rioja wine.

History of Day of La Rioja

The history of La Rioja is marked by territorial disputes and invasions. The territory of La Rioja was inhabited by the tribes of the Berones, Autrigones, and the Vascones during Roman times, while in Medieval times, it was often a disputed territory. After a Muslim Invasion in 711, La Rioja fell into the Muslim domains of Al Andalus. This was followed by more disputes and invasions, which were then followed by — you guessed it — even more disputes and invasions.

The territory was divided between the provinces of Burgos and Soria as recently as the 19th century. Even France had its say. Napoleonic forces took over the region during the Peninsular War, keeping it with the French till 1814.

Historically, La Rioja formed part of different provinces in the area but became its own province in 1833. It was called the Province of Logroño. The province was renamed La Rioja in 1980, although Logroño is still the capital city.

Today, this community forms the least populated region of Spain with over 300,000 inhabitants. It also has its own flag with the colors red, white, green, and yellow. The residents of this region take a lot of pride in their land. Other events like the Vendimia Riojana are also celebrated in the region. It is held during the third week of September in Logroño to celebrate the grape harvest with festivities, including a parade of carts and bullfights.

Day of La Rioja timeline

1550 B.C. The Iberian Peninsula

The Bronze Age begins and the El Argar civilization starts to form.

19 B.C. The Romans Take Over

Spain falls under the Roman Empire.

1479 The New Kingdom is Formed

The Kingdom of Spain is formed when Ferdinand and Isabella become king and queen.

1931 Spain As We Know It

Spain becomes a republic.

Day of La Rioja Activities

Visit La Rioja

Bring Spain home

Treat your friends

Take a trip to La Rioja to see the festivities for yourself. Bask in the Day of La Riojaculture, food, and wine that makes this region so unique.

If you cannot visit La Rioja, then bring Spain to your home. Cook up some delicacies from La Rioja like Patatas a la Riojana, beef, or pork cheeks in Rioja red wine sauce and white asparagus.

Call your family and friends over and treat them to some delicious food made in La Rioja style. Open up a bottle of wine while you are at it.

5 Facts About Spain That Will Blow Your Mind

Spanish is widely spoken

The world’s first global empire

The world’s oldest restaurant

Spain has a tooth mouse

More bars than anywhere in Europe

Spanish is the world’s second-most spoken native language.

The Spanish traveled across the world and left their mark on the Americas and also controlled the Philippines for over 300 years.

Madrid has the oldest restaurant in the world, El Restaurante Botin, which was opened in 1725.

Spain has a unique version of the popular mythical tooth mouse called ‘Ratoncito Perez.’

Spain has the highest number of bars compared to other countries in Europe.

Why We Love Day of La Rioja

The Spaniards know how to have fun

They make some great art

It is beautiful

We love any reason to have a celebration! La Tomatina and the Haro wine festival are just some of the popular festivals held in Spain.

Some of the world’s most famous painters including Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dali, Goya, El Greco, and Velázquez all came from Spain. There is nothing better than appreciating a good work of art.

It does not matter if you are into food, wine, beaches, history, art, or architecture — Spain has it all. Spain is such a popular country that in 2018 the country had more visitors than the number of people who live there!

Source

#San Vicente de la Sonsierra#Haro#puente medieval#medieval bridge#Spain#Bodegas Roda#Ebro River#Church of Santo Tomás#La Rioja#vacation#travel#Basilica of la Vega by Bernardo de Munilla and Juan de Villanueva#Day of La Rioja#DayofLaRioja#9 June#original photography#summer 2021#landscape#cityscape#countryside#vineyard#architecture#mountains#España#Northern Spain#Southern Europe

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

tagged by @unopenablebox

last song: Under der linden by Walther von der Volgelweide, on Oliphant's CD Herz, Prich!

last movie: i watched ~20 minutes of Clueless today but otherwise i don't...do that.

last show: R & I are watching Jonathan Creek. First series it was because it was a good time, if uneven, at this point it's because they're making so many inexplicable bad choices

currently reading: in theory, John M. Ford's Aspects (i'm three pages in!); listening to an audiobook about the Napoleonic Wars (Alexander Mikaberidze, The Napoleonic Wars: A Global History. it's really nice to listen to a real historian after Andrew fucking Roberts' hero worship and armchair generalship.)

currently working on: unsuccessfully, a novel about a fantasy gentlewoman detective; more successfully, a scarf

fav color: any shade that has both blue and green in it. that whole teal/turquoise family.

sweet/savory/spicy: sweet but they're all good.

coffee/tea/cocoa: primarily tea but sometimes i get a strong desire for coffee, and i love hot chocolate but it's a more occasional thing than my ~3 mugs of tea a day.

craving: nothing specific, actually.

tagging @aldieb @aeschylus-stan-account @literarymagpie @youcanthandelthetruth

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

What started your interest in the War of 1812?

I have an answer to this specific question! Probably a predictable one! My interest in the War of 1812 is directly tied to my interest in the novelist and Royal Navy officer Captain Frederick Marryat, who was a War of 1812 veteran among many other things. (To my amusement, the inferior second edition of Amy Miller's Dressed to Kill identifies Marryat as ONLY a War of 1812 veteran, when usually that's a neglected part of his biography).

Marryat's War of 1812 experiences are mostly described in his heavily autobiographical novel Frank Mildmay, although they also come up in his nonfiction travelogue Diary in America, written in the late 1830s. In Diary in America Marryat talks with American veterans, makes remarks on former warzones, and gets teased by bratty American kids.

After Marryat sparked my interest, I began to appreciate why the War of 1812 is not taught very much in US schools. I vaguely remember it being skimmed over, something about British harassment of American trade? And of course the USA totally won after many impressive victories—what do you mean we removed all of our original demands from the Treaty of Ghent and only restored the status quo ante bellum? What do you mean this was just an imperialist land grab and we openly threatened to invade Canada for years??

So it's a fascinating look into both US and Canadian history, deeply intertwined with our fractured relationship and broken promises to allied Indigenous nations, and slavery in the US and in the British Empire. I am very interested in the stories of Black War of 1812 veterans, and especially those who were promised safety in Canada and the West Indies (despite slavery being legal in the British Empire until 1833).

I cannot deny my love of Napoleonic-era military uniforms, which obviously includes the War of 1812. I have even seen the War of 1812 rolled into the global conflict of the Napoleonic Wars in analyses (hey it's a lot of the same guys! They even sent Sharpe's Rifles the 95th Rifle Regiment from the Peninsular War to get slaughtered in New Orleans!)

#frederick marryat#war of 1812#us history#canadian history#war that makes the british empire look like the good guys#shaun talks

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

A few weeks ago, I posed a hypothetical to a dozen foreign policy scholars, pundits, analysts, and ex-diplomats, American and not. Imagine, I wrote, a terrible denouement to the Ukraine war, though one that stopped short of World War III: a Russian decision to use tactical nukes against Ukraine, followed by a selective NATO strike on Russian air bases, followed by a Russian attack on one of the Baltic nations, followed by a devastating air assault on Russia.

My question was: In the aftermath of such a cataclysm, how would, or should, the world order be rebuilt?

My question rested on several assumptions. The first is that we do, in fact, live inside a “rules-based order” or “liberal” order: a network of norms, laws and institutions that, for all their shortcomings, govern international affairs not by raw power but by the rule of law. The second assumption is that such systems of order do not come into being because they sound like a good idea but because a catastrophe shows the existing framework to be untenable. The Napoleonic wars led to the balance-of-power system known as the Concert of Europe, World War I led to the League of Nations, and World War II led to the United Nations, the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, NATO, and other regional treaty alliances.

The final assumption is that our 75-year-old system is already unequal to the problems we face; The awful bloodshed, and the terror of yet worse, that my scenario envisioned would force statesmen to address that failure. In the most obvious sense, the U.N. Security Council has never functioned as the apex security body that Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Winston Churchill imagined it would be. Though Article 1 of the U.N. Charter declares state sovereignty to be inviolable, the Security Council could do nothing to stop Russia from trying to annihilate its neighbor. What is new is that, as the Biden administration’s recently released National Security Strategy asserts, the rules-based order is itself under threat from great powers with “revisionist foreign policies.” That is shorthand for Russia and China, and to a lesser extent Iran. But the authors obliquely concede that many democracies outside the West and the “Indo-Pacific” do not share a sense of urgency about challenges to that order, at least if they come from the revisionist powers.

What, then, would we do if we could? The answers I got were shaped by the author’s view of the gravest problems the world would face in the aftermath of my scenario. Thus Anne-Marie Slaughter, the former Obama administration State Department official who now runs the New America think tank, wrote that she welcomed the assertion in the Biden strategy document that global crises like climate change, pandemics, or food security pose as great a threat to the world as do the revisionist states. Global problems require global institutions. Therefore, Slaughter wrote, if she could “wave a wand,” she would invent a Security Council with 25 members with weighted voting rather a veto, an Economic and Social Council, and a Global Information and Monitoring Council, all staffed by senior government ministers with the power to propose initiatives, like the European Union’s European Commission. This U.N. would be both more representative, and more effective, than the one we have today.

Such a U.N. might be able to devise and execute policy on the global issues as the current version cannot. But would the United States trust it on matters of national security in the aftermath of a close brush with World War III? That seems hard to believe. Michel Duclos, a former French diplomat and now a resident sage at the Institut Montaigne, France’s leading liberal think tank, wrote that he finds the kind of scenario I suggested all too plausible. In such a case, he predicts, the Security Council would be deposited in history’s dustbin, while an “informal directoire,” consisting perhaps of the United States, China, India, and the E.U., would emerge.

Others have been thinking along the same lines. Richard Haass and Charles Kupchan, president and senior fellow, respectively, at the Council on Foreign Relations, have suggested an informal “concert of powers” with no actual executive powers but with a permanent secretariat that could engage in quiet diplomacy and “sustained consultation and negotiation,” much like the order hatched from the 1815 Congress of Vienna.

All such plans may founder on the question of membership. Major developing world powers will feel excluded. Others may be included who ought not be. Writing in 2021, Haass and Kupchan proposed a concert of the United States, Japan, India, the E.U., China—and Russia. In 1945, Roosevelt considered Joseph Stalin a fit partner for the new Security Council. By the following year, it was plain that he had been wrong. So too, today. Might we not say the same tomorrow of China?

Several of my respondents argued that my scenario would lead, not to a new moment of creation, but to a new fragmentation. Given the deep skepticism in the developing world over U.S. President Joe Biden’s framing of “democracies versus autocracies,” Richard Gowan, U.N. director for the International Crisis Group, suggests that “African, Asian and other non-Western leaders would likely look to regional clubs” like the African Union or Association of Southeast Asian Nations, while Western nations would seek to fortify NATO. Any new act of founding, Gowan suggests, would be patchwork. “The resulting ‘order,’” he writes, “would be a lot messier than what we know today.” We might even become nostalgic for the Security Council.

Others accused me of fetishizing institutions, as if they mattered more than the conduct of states. Robert Kagan, the foreign policy pundit and historian, wrote, “I feel like the actual system, which has nothing to do with the UNSC and everything to do with the American-backed liberal hegemony, is working as it always has—defeating and/bankrupting its challengers.” The calamity I imagine would simply reinforce the central role of the United States in policing the world order. The real problem with the current system, writes Brian Katulis, vice president of policy at the Middle East Institute, “is not the system itself but the assumption many people hold that it exists independent of its constituent states and can serve as a world government-in-waiting.” NATO and the Western alliance system have held up quite well in the Russian crisis. We should expect them to evolve as the world does, rather than wait for “a blueprint either handed down from Washington or hammered out in Geneva.”

Would things really stay much the same after we peered over the edge of World War III? I doubt that. To many, especially in the Global South, as Gowan observed, the idea that a “liberal order” exists, much less that it is threatened sounds like self-aggrandizing Western cant. Perhaps it would not after Russia raised the stakes so drastically. Much will depend on the attitude of China. The Biden administration has consistently described China under the increasingly bellicose Xi Jinping as a more grave and long-term threat to the existing order than is Russia. Would Xi regard a European military catastrophe as a warning of the unanticipated consequences of aggression? Or as yet another convulsion inside the West that strengthens his hand and thus further emboldens him to take Taiwan and extend control in the South China Sea? If the latter, any new security order incorporating China would reproduce the paralysis of the Security Council.

Here is the nut of the problem. In the first European order, the Westphalian system, states representing irreconcilable worldviews—Catholic and Protestant—agreed not to disturb or contest each other’s internal order. Today, however, both the West and China are seeking to shape a global order in conformity with their own values. The West could seek to exclude China, as the diplomats who gathered at the Congress of Vienna sought to contain republican France. But the great global problems cannot be solved without China. What is more, China’s immense influence would prevent many states from joining a new security body from which it had been excluded. You can live without Russia. You cannot live without China.

What then? My own answer is, first, that we need a much more effective global organization as a means to formulate solutions to global problems with the full engagement of the developing world. We cannot abandon the Security Council without provoking outrage, especially from countries like India that have been waiting their turn for membership. Perhaps the Security Council should be democratized as Slaughter suggests. But the great powers would continue to take their security concerns elsewhere.

The Biden National Security Strategy boasts of the security bodies it has formed or fortified, especially in China’s neighborhood: AUKUS (Australia, the United Kingdom, and United States) and the Quad (the United States, India, Australia, and Japan). Would it, after the catastrophe I imagine, seek to stitch them together into a single body? Could we envision a NATO that sheds its geographical boundaries or a version of the OECD that takes on security issues, that is, a body that brings together states that see their own security bound up with the existing order?