Text

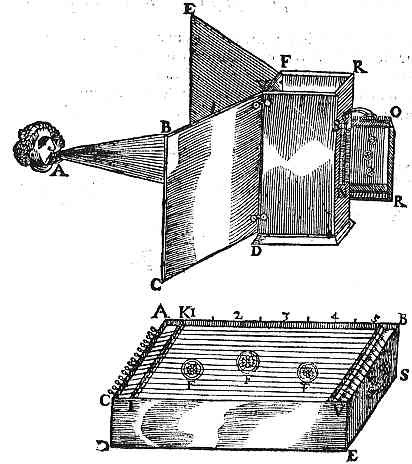

Aeolian harps, window-mounted (Kircher, 1673) and floor units (Frost and Kastner, 1853)

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Every one knew how laborious the usual method is of attaining to arts and sciences; whereas, by his contrivance, the most ignorant person, at a reasonable charge, and with a little bodily labour, might write books in philosophy, poetry, politics, laws, mathematics, and theology, without the least assistance from genius or study. He then led me to the frame, about the sides, whereof all his pupils stood in ranks. It was twenty feet square, placed in the middle of the room. The superfices was composed of several bits of wood, about the bigness of a die, but some larger than others. They were all linked together by slender wires. These bits of wood were covered, on every square, with paper pasted on them; and on these papers were written all the words of their language, in their several moods, tenses, and declensions; but without any order. The professor then desired me 'to observe; for he was going to set his engine at work.' The pupils, at his command, took each of them hold of an iron handle, whereof there were forty fixed round the edges of the frame; and giving them a sudden turn, the whole disposition of the words was entirely changed. He then commanded six-and-thirty of the lads, to read the several lines softly, as they appeared upon the frame; and where they found three or four words together that might make part of a sentence, they dictated to the four remaining boys, who were scribes. This work was repeated three or four times, and at every turn, the engine was so contrived, that the words shifted into new places, as the square bits of wood moved upside down."

Jonathan Swift, Gulliver's Travels (1726)

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vernacular Word Clouds and Information Aesthetics

“The purpose of reduced language is not the reduction of language itself but the achievement of greater flexibility and freedom of communication (with its inherent need for rules and regulations). The resulting poems should be, if possible, as easily understood as signs in airports and traffic signs.”

—Eugen Gomringer, “The Poem as Functional Object” (1960)

“The first thing that becomes clear to anyone who compares the dream-content with the dream-thoughts is that a work of condensation on a large scale has been carried out.”

—Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams (1899)

“What is happening?!”

—User input prompt, Twitter (2023)

A juice bar has words expanding across its window. The words are: “Cheers to nature,” “positive,” “passion,” “good,” “wellness,” “cure,” “happiness,” “watermelonade,” freshness,” “serenity,” “kale delight,” “relaxation,” “peanut butter oatmeal,” “calm,” “lifestyle,” “wheatgrass,” “sharing,” “wellness,” “whole greens,” “joy,” energizer,” “positive,” “protein supreme,” “healthy,” “organic,” and “life.” The terms are arranged an in amorphous cluster, in a nondescript (vaguely Grotesk) typeface, in a range of sizes, either parallel or perpendicular to one another. Since it is vinyl on glass, the cluster of words floats in the air. The words face out towards the street, although they just as well might appear on an interior wall. They advertise the business to passerby, inventorying possible experiences that might take place. Unlike more conventional awning or window signage, which might linearly list the products and services offered, these words take up the aesthetics of a diffuse field, with blurry edges. And just as the field is relatively indifferent to the form of its support, the rectangular window, it is also relatively indifferent to the level of concreteness and specificity of each of the terms it contains. The term joy is a member of the same set as the term peanut butter oatmeal, and is represented at the same scale.

Word clouds are not an uncommon feature of the contemporary graphic environment. They are not exactly ubiquitous, but they appear throughout metropolitan landscapes as interstitial visual clutter, in contexts where we are rarely anything other than indifferent to their presence: grocery stores, apartment buildings, hotels, fast-food restaurants, shopping malls, airports, corporate offices. They are indigenous to what the architect Rem Koolhaas called “junkspace”: an uncoordinated proliferation of shapeless filler, with its “superstrings of graphics,” its “fabrication of non-existent plurals,” its “fuzzy empire of blur” (“flamboyant yet unmemorable, like a screensaver”). But these formless textual forms are even more particular in a historical sense. They are not reducible to postmodernism, although they inherit its flatness. And while they have no connections to any definite style in art or design today—although they may echo the avant-garde textual experiments of artistic movements like Symbolism, Constructivism, Dada, and concretism, for which the collision of linguistic signs in nonlinear space still represented a revolutionary moment—they are unmistakably very recent, and very medium-specific. They are the forms of a residual Web 2.0, ornaments of a computational culture in which the aesthetics of the historical avant-gardes were banalized in software. Today, the everyday word cloud is more recognizable as an architectural derivative of software, a derivative that has discarded its origins in statistical analysis and UX design, let alone any origins in concrete poetry. The movement of the word cloud is the movement of informatics and interfaces into decorative vernaculars, registering our diffuse, formless present.

What is a word cloud? It is a set of terms—words, phrases, and in rare cases complete sentences—arranged in a cluster or constellation. It is free-associative, impressionistic, asyntactic. It is atmospheric, a brainstorm. It is an accumulation of themes. It is probably set in an inelegant or kitschy typeface. It is an array of opaque and possibly hallucinated correlations. Its terms do not create meaningful sequences, but are simply adjacent or orthogonal to one another. If they create anything, it is a mood or a vibe, a loose bundle of co-occurrences that may be felt. A word cloud is scanned, not read. To use Robert Smithson’s phrase, a word cloud is “language to be looked at.”

What is immediately recognizable in the decorative word cloud, the architectural word cloud, is a specific relationship between possible experiences and their description. As wallpaper, word clouds fulfill the need to put something on the wall, to fill space, and at the same time they communicate something about a place and about experiences associated with that place. The wall of an Arby’s fills up with terms like “signature,” “oven roasted,” “market fresh ingredients,” “hand crafted sandwiches,” and “Arby’s roast beef sandwich is delicious.” The wall of a Bushwick apartment building fills up with terms like “new,” “housing,” “social,” “avenue,” “street,” “future,” and “old city.” This communication is both too little and too much. It accomplishes the minimal task of naming some of the things that might go on here, some of the things (feelings, products, values, referents, connotations) on offer, but in a way that has the appearance of overactivity, busy-ness. It has parsed, labeled, and filtered the data of the experience we (as prospective consumers) are potentially having, but clarifies nothing. It leaves behind a mess; it is the entropic residue of taxonomy. Like almost everything in a designed environment, it has attempted to calibrate and nudge our attention without making overbearing demands upon it. Yet the coarseness and triviality of its matter—language in an ugly font—seems to fail in this regard. If we find word clouds unpleasant, it is because they are clumsily explicit, neither ignorable nor interesting. They name the obvious. They stupidly say words without composing them. They appear to preempt our own powers of description and association, describing and associating for us, but they are also completely unconvincing. It is as though the very first stage of a marketing project, the brainstorming or moodboarding stage, in which the product or brand is “ideated” upon, sufficed for a final design. There is no development beyond the whiteboard.

The word cloud, as a mode of textuality, cannot be conceived outside of computational culture. This is not only because it is produced using digital tools, or because it coincides with certain algorithmic operations (of theme detection, for instance, or the computing of taste), but because it has developed directly from data visualization techniques. In data visualization, a word cloud (or term cloud or tag cloud) is a technical image-text that synthesizes the contents of a set of data by arranging and scaling its terms according to a logic of measurement. What is most straightforwardly measured in this kind of word cloud is frequency. The more times a datum appears in the set, the larger its text may appear. This relation can then be adjusted using other statistical parameters, such as deviation from some other distribution. Sometimes the words are also plotted in space, in which case positionality becomes meaningful (although this would probably be called a scatter plot rather than a word cloud). In any case, the aim is to summarize data, to give humans a more or less immediate impression of can be found in the data.

UX design researchers have located the earliest word cloud (at least in its data-visualization capacity) in a 1976 paper by psychologist Stanley Milgram, who surveyed residents of Paris and mapped the terms they used. A word cloud also appears prominently on the cover of the first German-language edition of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus (1991), “rhizomatically” showcasing the text’s most idiosyncratic concepts. Douglas Coupland, in his third novel, Microserfs (1995), uses word clouds to model the keywords in “subconscious files,” the imaginary dream-work of a Microsoft employee’s personal computer. Following these precedents, the tag cloud became a trope of early Web 2.0 design, most notably on the social photo site Flickr (2004–) and the social bookmarking site del.icio.us (2003–2017). Here, the words in the cloud were pieces of ad-hoc, user-generated metadata, or “folksonomy,” terms constantly and conjunctively attached by users to content (which may or may not have actually included these terms). And much like Milgram’s survey of Parisians, the social media tag cloud provides a sense of what people are talking (posting) about. The cloud becomes an interface, a clickable map of labels through which one can navigate a database.

So perhaps we see in the latter-day word cloud—the one on the wall of the juice bar—not only the condensation of the taxonomic or statistical, but also the condensation of the social. Perhaps in the nimbus of terms on the fast-casual restaurant wallpaper we are supposed to be hearing the polyphony of the multitude, a “network power,” a “living alternative.” It may be that we are meant to believe that these are not just the statements of a brand but the voices of “community stakeholders” (and satisfied customers). Meanwhile, new algorithms have automated or augmented social tagging practices. New interfaces, too, have reduced the presence of tag clouds online, opting for single-stream content flows or “feeds” (Instagram, TikTok, Spotify) in which linguistic description does not have a prominent mapping or labeling function for the (sighted) end user. The original function of the tag cloud—summarizing a whole—no longer seems important once content delivery, with the help of machine learning, becomes hyper-individualized, and much more passive for the end user (who can only nudge the algorithm). There is no question of a single database of which to have an impression. The clouds appeared to have receded.

The German philosopher and founder of “information aesthetics” Max Bense argued that works of literary art were not so different from any other source of information. “Aesthetic realizations,” he argued in 1960, can be “described through statistical quantities of conditions instead of irrational motives of values.” He described text in atmospheric terms; for Bense, there was no text that was not a cloud. Texts are like “gaseous spaces,” as Claude Shannon’s information theory already recognized when it sought to translate thermodynamic particles as linguistic particles. Information theory has not changed much; today’s “deep dreaming” algorithms, such as AI diffusion models, work by introducing gaseous noise into training data that they then filter out in order to generate new outputs. The clouds are condensed and displaced, a dream-work written not only by psyches but also by machines. The word cloud may be a degraded form, but clouds of words remain.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hollis Frampton, "A Stipulation of Terms From Maternal Hopi" (1973/75)

1. [] = The radiance.

2. ]D[]Y[ = Containers to be opened in total darkness.

3. ]PS[]L[ = A drug used by women to dilate the iris of the eye.

4. ]H[]H[]L[ = Epithet of the star ]S[]S[]N[*, used while succulents are in bloom.

5. ]PT[]Y] = Last light seen by one dying in the fifth duodecad of life.

6. ]XN[ = Heliotrope.

7. ]TL[]D[ = Rotating phosphenes of 6 or 8 arms.

8. ]BN[]T[ = Shadow cast by light of lesser density upon light of greater.

9. ]V[]TR[ = The pineal body; time.

10. ]XR[ = The sensation of sadness at having slept through a shower of meteors.

11. ]MR[][ = The luster of resin from the shrub ]R[]R[, which fascinates male babies.

12. ]NX[]KT[ = The light that congeals about vaguely imagined objects.

13. ]DR[]KL[ = Phosphorescence of one's father, exposed after death.

14. ]SM[]N[ = Fireworks in celebration of afirstborn daughter.

15. ]GN[]T[]N[ = Translucence of human flesh.

16. ]TM[]X[]T[ = Delight at sensing that one is about to awaken.

17. ]TS[]H[ = Shadow cast by the comet ]XT[ uponthe surface of the sun.

18. ]R[]D[ = An afterimage. **

19. ]D[]DR[ = A white supernova reported by alien traveller.

20. ]K[]SK[ = A cloud; mons Veneris.

21. ][]Z[]S[= Ceremonial lenses, made ofice brought down from the high mountains.

22. ]KD[]X[ = Winter moonlight, refracted by a glass vessel filled with the beverage ]NK[]T[.

23. ]P[]M[]R[ = Changes in daylight initiated by the arrival of a beloved person unrelated to one.

24. ]G[]S[ = Gridded lightning seen by those born blind.

25. ]W[]N[]T[ = An otherwise unexplained fire in a dwelling inhabited only by women.

26. ]G[]GN[ = The sensation of desiring to see the color of one's own urine.

27. ]M[]K[ = Snowblindness.

28. ]H[]R[ = Unexpected delight atseeing something formerly displeasing.

29. ]H[]ST[ = The arc of a rainbow defective in a single hue.

30. ]L[]L[]X[=The fovea of the retina; amnesia.

31. ][]R[ = The sensation of satisfaction at having outstared a baby.

32. ]ST[ = Improvised couplets honoring St. Elmo's Fire.

33. ]V[]D[ = The sensation of indifference to transparency.

34. ]Z[]TS[ = Either ofthe colors brought to mind by the fragrance of plucked ]TR[ ferns.

35. ]X[]H[ = Royal expedition in search of a display of Aurora Borealis.

36. ]T[]K[]N[=Changes in day light that frighten dogs.

37. ]Y[]X[ = The optic chiasmus (Colloq.); abysmal; testicles.

38. ]N[][]T[ = The twenty-four heartbeats before the firstheartbeat ofsunrise.

39. ]F[]X[= A memory of the color violet, reported by those blinded in early infancy.

40. ]T[]Y[]Y[ = The sensation of being scrutinized by a reptile.

41. ]B[]NM[ = Mute.***

42. ]N[]T[]N[ =The sound of air in a cave; areverie lasting less than a lunar month; long dark hair.

43. ]S[]TY[ = The light that moves against the wind.

44. ]B[][ = Changes in one's shadow, after one's lover has departed in anger.

45. ]N[]GR[ = The fish Anableps, that sees in two worlds.

46. ]RZ[]R[ = The sensation of longing for an eclipse of the Moon.

47. ]H[]F[ = Stropharia cubensis.

48. ]S[]LR[ = Familiar objects within the vitreous humor.

49. ]W[]X[][ = A copper mirror that reflects only one's own face.

50. ]MN[]X[ = Temporary visions consequent upon trephining.

51. ]G[][]KR[ = Cataract.

52. ]RNpW[ = Hypnagogues incorporating unfamiliar birds.

53. ]M[]D[ = A dream of seeing through one eye only.

*Probably Fomalhaut (alpha Piscis Australis).

**Also used as a classifier of seeds.

***Standing epithet of ancestral deities.

PDF

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Techno-aesthetic Milieux: Dewey to Simondon

John Dewey and Gilbert Simondon are thinkers of media and milieux as the all-too-excluded middle of genesis. Like the so-called process philosophers, they think in terms of phase, transfer, prefiguration, virtuality, impulsion, and continuous function. Both share a rejection of the hylomorphic schema, or the dualist partition of form and matter, as well as a focus on the potential forces carried along with every becoming, and an understanding of the recurrent causality of dynamic wholes, in which every individual “unity”—in accordance with the biological model of the living thing—has its pre-individual milieu, a field of composability. Form is not a reality beyond matter but emerges in the circular dynamic of the individual’s interchange with its milieu. The technical individual in Simondon and the work of art in Dewey are derived from this dynamic. They are organizations or selections of energy from within a situation (a medium, a milieu, or an environment). These organizations or selections do not bring anything to the situation that was not already there (a form, an idea, a design, a telos). Instead, there is a crystallization, a shifting of the phase of the situation or the solution. The tensions and incompatibilities that saturate it are brought up to and beyond a certain limit, and the individual being comes into being, resolving those tensions and incompatibilities while also preserving them within a new, higher unity.

Dewey, unlike Simondon, is not widely known as a philosopher of technics. But there may also be a convergence between the two thinkers on the issue of what Simondon calls “techno-aesthetics or aesthetico-technics,” an aesthetics of technics and a technics of aesthetics. To be sure, this convergence is largely projective. Something like techno-aesthetics is discussed occasionally throughout Dewey’s Art as Experience (1934), but not at any sustained length, although a positive consideration of the possibilities of communication and industrial technology forms a significant part of the book’s concluding chapter, “Art and Civilization.” Similarly, Simondon devotes only some of On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects (1958) to art and aesthetics, and only really arrives at techno-aesthetics in a letter written late in his career (“On Techno-Aesthetics”). Though the concept of techno-aesthetics remains strangely marginal in the history of aesthetic theory, I want to propose that these two thinkers offer a particularly concrete and compelling foundation for its theoretical elaboration.

Dewey’s pragmatism and Simondon’s philosophy of technics—unlike the classical aesthetics of Hume, Kant, and Schiller—recognize the intertwining of technical media and human life in aesthetics: there is an aesthetic feeling that we have in our absorption in technical tasks (the use of a tool or a machine), a technics that we must account for in the production of artworks (the artist’s ongoing engagement with manufactured materials, tools, and techniques), a creative or aesthetic side to technical development, and a technosphere that affects our ways of sensing. But Dewey’s naturalism and biologism can occasionally seem to overstate the importance of the human’s relationship to nature, bracketing the role of technics—and especially industrial technics, or machines, and their “non-human modes of energy” (Art as Experience, 351)—in constituting the human, its environment, and its experience in the first place. For Dewey, the industrial or “mechanical” (Dewey’s preferred term) is usually the negation of an authentic aesthetics of art, which is always natural, not in the sense that it is unchanging or otherwise opposed to culture but in the sense that it is derived from and consummates the ongoing development of the organism—rather than the machine—in its environment. Culture does not stand opposed to nature, but “the mechanical stands at the pole opposite to that of the esthetic” (355), because it is composed only of discrete parts which are instances of types or models, whereas the “dominantly esthetic” is a dynamic whole made of organs that are in continuous relation, and which has communication with and development in an environment. Machines, it is implied, do not have environments. Indeed, Dewey often suggests that machine operations are responsible for the very problem he wants to address: the separation of fine art from the praxis of everyday life, and not just any life, but the “significant life of an organized community” (5).* Simondon, on the other hand, more directly questions the dominant understanding of industrial technics, arguing that “culture has constituted itself as a defense system against technics,” and has therefore failed to understand them, even as it makes use of them as instruments of domination and extraction (On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects, 15). Simondon might help us to make manifest some of Dewey’s latent modernist sympathies, recovering a vision of machines and humans working alongside each other. His thinking allows us to expand Dewey’s own limited application of the organism/environment model.

The term “techno-aesthetics [techno-esthétique]” appears in an unsent letter by Simondon to Jacques Derrida regarding the foundation of the Collège International de Philosophie in 1982. “If our fundamental aim is to revitalize contemporary philosophy, we should first of all think of interfaces . . . Why not think about founding and perhaps even provisionally axiomatizing an aesthetico-technics or techno-aesthetics?” asks Simondon (1). With techno-aesthetics, Simondon is not primarily thinking of art that is “about” technology, although he does briefly mention Marinetti, Léger, and Xenakis. What techno-aesthetics offers is instead an “intercategorial axiology” that would examine the “contemplation and handling of tools,” the “perceptive-motoric and sensorial” intuition in the use of tools and the care of machines (2), “phanero-technics,” or the exposure of technical components or techniques (2), artworks that “call for a technical analysis” (4), and the “technicized landscape,” or the aesthetics of infrastructure (6). Simondon’s letter is relatively brief but wide-ranging, and it would be too much to enumerate all of the points of correspondence with Dewey’s project: the attempt to think aesthetics in production and not only in consumption (the aesthetic experience of “contact with matter that is being transformed through work,” of “soldering or driving in a long screw” [Simondon, 3]); the refusal, in principle, of the distinction between “useful or technological art” and “fine art” (Dewey, 27); the recognition of what Simondon calls a “margin of indeterminacy” or “margin of liberty” in all technical products that allows them to be “liberated from limitation to a specialized end,” to become “esthetic and not merely useful” (Dewey, 121), to be transferred between or to negotiate different milieux, and thereby to be newly concretized and individuated. What I want to focus on in particular is how Dewey and Simondon do or do not think the concepts of milieu and environment across the organic and machinic in relation to techno-aesthetics.

Dewey’s critique of aesthetics in Art as Experience wants to do justice to the ordinary “doing and undergoing” that is subjacent to fine art and philosophical reflection. It wants to re-situate art in and as collective experience. It wants to show that there is nothing inherent in art’s subject-matter that justifies the separation of art from experience, and that this separation can only be attributed to “specifiable extraneous conditions” that are “embedded in institutions and in habits of life,” operating “unconsciously” (9). In order to perform this critique, a basic and universal theory of experience must be initialized. Dewey’s theory is schematically biological; he does not begin, like the Enlightenment empiricists, with the constant succession of individual impressions in the mind, nor with the Cartesian division of subject and object, but with something like Jakob von Uexküll’s proto-cybernetic interchange between organism and environment (its Umwelt, in Uexküll’s vocabulary, or its milieu, in Simondon’s). Every living thing comes in and out of step with its environment by responding to it, by making adjustments, by having directionality or impulsions. This is all immanent in sense experience. Dewey narrates the process by which (aesthetic) form, which he defines as “consummation” or “integral fulfillment” (142), emerges:

The world is full of things that are indifferent and even hostile to life; the very processes by which life is maintained tend to throw it out of gear with its surroundings. Nevertheless, if life continues and if in continuing it expands, there is an overcoming of factors of opposition and conflict; there is a transformation of them into differentiated aspects of a higher powered and more significant life . . . Here in germ are balance and harmony attained through rhythm. Equilibrium comes about not mechanically and inertly but out of, and because of, tension.

There is in nature, even below the level of life, something more than mere flux and change. Form is arrived at whenever a stable, even though moving, equilibrium is reached. Changes interlock and sustain one another. Wherever there is this coherence there is endurance. Order is not imposed from without but is made out of the relations of harmonious interactions that energies bear to one another. (13)

We have here something very similar to the cybernetic theory of information later proposed by Dewey’s student Norbert Wiener: the negentropy of a responsive life that periodically establishes form and pattern as temporary or metastable equilibria amidst quasi-entropy. (Unlike Wiener, Dewey believes that this information cannot be generated “mechanically.”) We might also detect, in the language of “overcoming of factors of opposition” and differentiation into a “higher” form of life, the shadow of Hegel, but Dewey’s opposition is not between sense and intellect. There is a becoming-conscious that is proper to the human, but sense and intellect are not discernible in it. Dewey will associate the compartmentalization of sense and intellect with the division of intellectual and manual labor, with the Cartesian dualism of matter and spirit, with the Kantian schema of the faculties, with the theoretical and institutional scission of art from experience, and with the mechanical: the application of the “bare outline as a stencil” (54), or the imposition of “some old model fixed like a blueprint” in the mind (52).

Art and aesthetic experience, unlike the “mechanical,” are prefigured in the natural feedback processes of “living,” and it is with the conscious “regulation,” “selection,” and “redisposition” of the matter of sense “on the plane of meaning” (26) that we get works of art. In other words, in its production of “dynamic organizations” (57), art does not impose form or design on a raw, unformed matter of experience. “Design, plan, order, pattern, purpose” emerge from materials that are already saturated with potential organizations (26). Experience, or the milieu from which the work of art emerges, is no more flux or chaotic substratum than it is a succession of stable forms. Experience and the “pre-individual” milieu are infrastructural, saturated with virtually formed matters, which can be actualized and thereby socialized as metastable forms, or works of art, which can then always shift in and out of phase with their environments.

For Simondon, who is writing both with and against Wiener’s and Claude Shannon’s respective theories of information, individual things or beings are likewise never the products of predetermined forms stamped onto shapeless, unformed matter. This is the “hylomorphic schema” that Simondon associates with the major tradition of Western philosophy, and which he wants to dismantle first and foremost.** As explicated in Individuation in Light of Notions of Form and Information (1964), individual beings are the outcome of a process of transduction which tries to resolve incompatibilities between milieux, or to relate initially non-communicating regions of a milieu. The resulting state is always metastable, not stagnant, not absolutely but relatively complete. This is also true of the “integral fulfillment” that constitutes an individual artwork for Dewey: “consummation is relative; instead of occurring once and for all at a given point, it is recurrent” (143).

Dewey feels the need to oppose this “recurrence” of the “consummatory phase” with the mechanical. Recurrence “sets the insuperable barrier between mechanical production and use and esthetic creation and perception. In the former there are no ends until the final end is reached . . . But there is no final term in appreciation of a work of art” (145). Yet for Simondon, actual technical beings (tools, machines, apparatuses) individuate in a way that is explicitly analogous and not at all opposed to the way living things, and by extension works of art, individuate. The individuation of technical beings is “made possible by the recurrence of causality within a milieu that the technical object creates around itself and that conditions it, just as it is conditioned by it” (On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects, 59). The milieu is both natural and technical—Simondon calls it an “associated milieu.” This milieu changes in ways that escape predetermined human ends according to a “margin of indeterminacy” within the situation, which is the condition of technical development. “The unity of the technical object’s associated milieu is analogous to the unity of the living being” (60). Dewey seems less certain. Like the artwork, “every machine, every utensil, has, within limits, a similar reciprocal adaptation,” he says. “In each case, an end is fulfilled. That which is merely a utility satisfies, however, a particular and limited end.” On the contrary, “the work of esthetic art satisfies many ends, none of which is laid down in advance” (140). But elsewhere, Dewey admits, as we have already seen, that any utensil can be “liberated from limitation to a specialized end” (121). The instability of an inorganic and closed essence of useful objects as opposed to an organic and open essence of aesthetic objects, can only be finally resolved, it seems, by an appeal to social determination, by a tentative historical materialism: “Much of the current opposition of objects of beauty and use—to use the antithesis most frequently used—is due to dislocations that have their origin in the economic system” (271). Can the conditions under which technical objects would be as open as artworks be positively articulated?

In his brief letter, Simondon wants to show us that there is a beauty even in those dislocations, in those monstrosities of industrial capital and mass communication, those “places of production and emission,” that escapes the economic horizon, and that entails a different kind of techno-aesthetic autonomy than Dewey has in mind. I want to conclude with one of Simondon’s examples, which in a strange way might have also been one of Dewey’s. Many of the objects that Simondon discusses in “On Techno-Aesthetics” are opposed to an aesthetics that sees only instrumentality, unresponsiveness, and a lack of milieu in industrial technics. Simondon’s descriptions of the antennas of the Eiffel Tower, Corbusier’s chapel of Notre-Dame du Haut, the Garabit viaduct, and the antennas on the plateau of Villebon are like counter-images of Heidegger’s hydroelectric dam on the Rhine—which enframes nature by revealing it only as a “standing-reserve” [Bestand]—or parodies of his silver chalice and its fourfold causality. To Simondon, the “technicized landscape also takes on the meaning of a work of art” (6).

The plateau of Villebon is constituted and structured on its east side by a field of emission antennas. The highest one is that of France-Culture. Its height was reduced from eighty to forty meters because of the planes passing to land at Orly. But it has preserved a certain majesty. There is also the antenna of the Paris-IV-Villebon emitter, which helps diffuse Radio-Sorbonne. And there are several others. This field of antennas is evidently first of all made up by each antenna by itself, and for itself. They are pylons that are generally propped up several times, with the support structures being cut in several segments by insulators so as to reduce the resonance phenomena that would otherwise absorb part of the radiation. This structure is very remarkable, especially because it cannot be found in nature. It is completely artificial, unless perhaps one would recognize it in the sacred fig tree. This tree has several points of support and subsistence on the ground thanks to the roots that its branches let down, all the way to the ground, where they dig themselves in. This enables them to support their branches.

[. . .]

A group of emission antennas is a kind of set, like a forest of metal, and it can remind one of the rigging of a sailboat. This set has intense semantic power. These wires, these pylons radiate in space, and each leaf of the tree, each blade of grass, even if it’s hundreds of kilometers away, receives an infinitesimally small fraction of this radiation. The antenna is immobile, and yet it radiates. It is, as the English word has it, an “aerial,” something of the air. And indeed, the antenna plays with the sky into which it cuts. It is a structure that cuts into the clouds or into a light-colored background. It is part of a certain aerial space over which it sometimes fights with airplanes, as the example of France-Culture demonstrates. Even on a car, an antenna—especially if it’s an emission antenna—, testifies to the existence of an energetic, non-material world. (5)

Here, at an infrastructural site, there is an aesthetic beauty that emerges from the experience of a utility that is diffuse and invisible—the radio network—as well as an apparent integration between the network, the plateau, the atmosphere, and finally the end users. (Divinities, earth, sky, mortals.) This would make it perversely coincident with Heidegger’s artwork just as much as with Dewey’s: it is quite literally a selection, filtering, and organization of energies that also determine its form, and that would otherwise remain below the level of “an experience.” But it is not clear that the aesthetic feeling has to do completely with our participation in this environment or with our continuity with it, nor even with the possibility of communication that the antennas signify. It may be the silent distance or disjunction of our world from the milieu of the antennas that strikes us most immediately, not our overcoming of them or enduring of them. The radio network is, obviously, a practical part of the significant life of a community. And undoubtedly, if we are even discussing the antenna array, for instance, as a consummating experience, we are speaking of a human experience. But Simondon’s point is simply that it is important that the antenna array has performed, and continues to perform, a kind of consummation that does not immediately concern us, and that this has not been concealed.

*While there are clear affinities here with Martin Heidegger’s aesthetics, Dewey gives us slightly more specificity than Heidegger, who associates the separation of poiesis from substantial communal life with a mystifying “forgetting of Being” or “abandonment of Being.” Dewey attributes the division of art from life and techne from poiesis to historical conditions such as nationalism, imperialism, industrial production, and global capitalism, all of which have yielded a disarticulation of the social coherence of art that was imagined to exist in ancient Greece. The extent to which such a social totality has ever empirically existed is a question that does not particularly interest either Dewey or Heidegger.

**Here is Dewey’s version of the hylomorphic schema: “Form was treated as something intrinsic, as the very essence of a thing in virtue of the metaphysical structure of the universe . . . it was concluded that form is the rational, the intelligible, element in the objects and events of the world. Then it was set over against “matter,” the latter being the irrational, the inherently chaotic and fluctuating, stuff upon which form was impressed. It was as eternal as the latter was shifting. The metaphysical distinction of matter and form was embodied in the philosophy that ruled European thought for centuries” (120).

Works Cited

Dewey, John. Art As Experience. Penguin, 1934.

———. Democracy and Education. Macmillan, 1916.

Heidegger, Martin. “Building Dwelling Thinking.” 1951. Poetry, Language, Thought. Translated by Albert Hofstadter, Harper Colophon, 1971.

———. “The Question Concerning Technology.” 1954. Translated by Taylor Carman, Harper Perennial, 2008, pp. 307–342.

Simondon, Gilbert. Individuation in Light of Notions of Form and Information. 1964. Translated by Taylor Adkins, University of Minnesota Press, 2020.

———. On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects. 1958. Translated by Cecile Malaspina and John Rogove, Univocal, 2016.

———. “On Techno-Aesthetics.” Translated by Arne De Boever, Parrhesia no. 14, 2012, pp. 1–8.

Uexküll, Jakob von. A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans with A Theory of Meaning. 1934. Translated by Joseph D. O’Neil, University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

Wiener, Norbert. Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine.1948. The MIT Press, 1965.

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

Berlin Alexanderplatz Original Soundtrack, Peer Raben

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Peter, Artificial versifying, or, The school-boy's recreation : a new way to make Latin verses : whereby any one of ordinary capacity, that only knows the A.B.C. and can count 9 (though he understands not one word of Latin, or what a verse means) may be plainly taught, (and in as little a time as this is reading over, ) how to make hundreds of hexameter verses, which shall be true Latin, true verse, and good sense. Never before publish'd (1677)

1 note

·

View note

Text

History, Narrative, and the Cybernetic-Structuralist Database

Is what Roland Barthes called the “structuralist activity” an algorithm? Structuralism certainly seems to proceed, in its various instantiations, in an algorithmic manner, setting up rules that could be used to process any data loaded into the memory of literary analysis. Barthes defines the "activity" as “the controlled succession of a certain number of mental operations” (1963, 214). For structuralism, these are primarily operations of decomposition and recomposition, taking “the real” as an input, “decomposing and recomposing” it in an operational form to be worked on by the new literary scientists (215). An algorithm, strictly speaking, is a finite set of explicit and definite steps that takes an input and yields an output (Knuth 1997, 4–6). Of course, the “structuralist activity” is not literally an algorithm—its steps are by no means definite, even within the oeuvres of individual authors—but it does emphasize machine-like operations, foregrounding the ways in which it formalizes its concepts: by means of measure, selection, permutation, binary opposition, code, unit, function, and so forth, all terms which would not have been commonly found in traditional studies of literary language, which was largely philological and rhetorical (what Barthes calls the “old Rhetoric”). The “new Rhetoric” of structuralism was an attempt to confront “the new semiotics of writing,” and the “modern text, i.e., the text which does not yet exist” (Barthes 1985, 11).

The structural analysis of the “modern text” turns out to be closely—though not exhaustively or exclusively—engaged with the digital and the computational: a digital humanities avant la lettre. It is not only coincidentally similar in its broad outlines to developments in algorithmic and information-technological thinking, but actively drew on such thinking, transcoding it into cultural and literary studies (and at times subverting it, by extending it to an absurd degree). The foundational texts of structuralist narratology, in particular—such as those published by the journal of the Centre d’études des communications de masse [Center for the Study of Mass Communications] (CECMAS) at the École Pratique des Hautes Études in Paris, authored by theorists like Barthes, Claude Bremond, Gérard Genette, Tzvetan Todorov, Umberto Eco, A.-J. Greimas, Christian Metz, and others—introduce a database logic that sometimes seems to threaten the epistemic dominance of narrative, creating anxieties about the disappearance of historical meaning. This tension between databases and narratives, which Lev Manovich emphasizes much later in his book The Language of New Media (2001), is of course still relevant today, amidst major expansions of data science, artificial intelligence, algorithmic culture, and computational literary studies. A return to the history of structuralism and semiology and its genesis in what Ronald R. Kline calls the “cybernetics moment” reveals that much of the cultural-technical background has been lost in the reception of these innovative twentieth-century approaches.

Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan has recently shown (2023) how so-called French structuralism emerged from a circuit of trans-Atlantic exchange between the human sciences in Europe and the new “universal sciences” of communication and control in North America (cybernetics, information theory). European émigrés like Roman Jakobson and Claude Lévi-Strauss were among the first to popularize the hybridization of Saussurean linguistics with these new sciences: Jakobson with his reinterpretation of the Shannon-Weaver model of communication (channels and messages, senders and receivers), and Lévi-Strauss with his ambitions of organizing the large-scale storage and processing of (largely endangered) myths. Both received support from major US private philanthropic and government institutions, such as the Rockefeller Foundation and the CIA-founded Center for International Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Later, in the 1960s, scholars like Barthes, responding to the technocratic, scientistic ambitions of the French state and its modernizing universities, would also take up cybernetic-structuralist thought. But they would do so more ironically than their predecessors. CECMAS, founded in 1960 by sociologist Georges Friedmann (with assistance from Barthes, Edgar Morin, and Violette Morin), became a launch pad for what Geoghegan calls “crypto-structuralism,” a retranslation of cybernetics and information theory, undertaken after these ideas had already been circulating between the US and France for around a decade. This loose group, which included Jean Baudrillard and Julia Kristeva among those already mentioned, did not reject cybernetics altogether, as many of its peers did. But it also did not import cybernetic concepts wholesale. In the writing of “crypto-structuralists” like Barthes, as we have already begun to see, there is a historicizing tendency that suggests that these thinkers may have viewed cybernetics as an interesting and useful apparatus for contending with a period of rapid information-technological change, and not necessarily as a universally applicable strategy.

One of the most influential issues of Communications, the journal of CECMAS, is the 1966 issue on narrative (“Recherches sémiologiques : l'analyse structurale du récit”). Yet narrative is largely absent from the North American communications research that CECMAS convened to study. Information theory and cybernetics are not theories of narrative; in some ways, they are antithetical to traditional concepts of narrative. The information theory of Shannon and Weaver, first published in 1948, consists of a set of five elements: an information source, a transmitter, a channel, a receiver, and a destination. A message from the source is “selected” and encoded into a technical signal, transmitted along an insulated channel, decoded by a receiver, and arrives, reconstituted, at its destination. According to this model, the channel is ideally always open, and noise-free. Similarly, cybernetics, at least as articulated by Norbert Wiener, does not deal with narratives but time series and feedback loops, seeking to develop a science of the “real-time” prediction of future behavior from past behavior in the direction of a system. Information theory and cybernetics are both probabilistic: they are oriented toward the optimization of systems according to patterns that are statistically likely. Where narrative is a recounting, these are systems of counting.

But the structural narratologists show us that recounting and counting are not necessarily so foreign to one another, or at least that it may be worth modeling the former in terms of the latter, as a kind of experiment in translation. Barthes, in an early statement on CECMAS in the social history journal Annales, uses terminology from information theory to describe the primary concept of structural analysis: the unité informative, the “smallest component element of a set.” CECMAS’s project, according to Barthes, is to investigate the ambiguity of this unit of information, which is two-sided, both quantitative and qualitative, statistical and structural, numerical and functional. It is not a matter of choosing between these two alternatives, says Barthes. Rather, “both paths are open to the mass-media researcher: such is the breadth and novelty of the work ahead” (1961, 992; my translation). Accordingly, the statistical thinking associated with information theory and cybernetics (to which we might also add game theory, decision theory, and operational research) consistently makes its way into the narratological work done by the structuralists: more or less all structural analyses of narratives begin by pronouncing the need for compression algorithms or source-codes, sets of rules that would allow us to know how narrative works without needing to read each and every narrative (an eternal task). In the Saussurean tradition, instead of following narratives primarily on the diachronic axis (as paroles), structuralism transforms them into relations on the synchronic axis (as langue). In the vocabulary of Shannon and Weaver, we might view this as the optimization of a narratological apparatus according to the “statistical structure” of narratives.

In his “Introduction to Structural Narratology” (1960), Barthes foregrounds structuralism’s idiosyncratic approach to narrative. “It has already been pointed out that structurally narrative institutes a confusion between consecution and consequence, temporality and logic. This ambiguity forms the central problem of narrative syntax. Is there an atemporal logic lying behind the temporality of narrative?” (98) An “atemporal matrix structure,” as Lévi-Strauss calls it, absorbs chronological succession. “Analysis today,” Barthes continues, “tends to ‘dechronologize’ the narrative continuum and to ‘relogicize’ it . . . the task is to succeed in giving a structural description of the chronological illusion—it is for narrative logic to account for narrative time” (99). In the same issue of Communications, Gérard Genette, Tzvetan Todorov, Umberto Eco, and Claude Bremond concur: narratives are “artificial,” full of “exclusions and restrictive conditions” (Genette 1976, 11); they are “games” or “play situations” (Eco, 155); “networks of possibilities” (Bremond, 388). They are not just continuous passages in time that readers or viewers must progress through; they are also structures in which units are correlated to other units, and beyond which these structures might be correlated to other structures.

What the structuralists discover is that it no longer makes sense to claim that narrative is fluid, continuous, analog, “natural.” Narrative is a complex operation of coding and transcoding, of organizing many time series in terms of many other time series, of decision trees, of anachronisms, focalizations, groupings, frequencies, speeds, and so on. This discovery, I would argue, is historically specific, conditioned not only by the narratologist’s modern objects (Genette’s À la recherche du temps perdu; Eco’s James Bond) but also by a techno-social situation: a Cold War context of burgeoning information capitalism and modernizing universities, the beginning of what Jean-François Lyotard would in 1979 call the “postmodern condition.” It seems that structuralist theorists were, with some exceptions, conscious of this conjuncture, and were working to develop a project adequate to it, under the political and economic pressures of the postwar period.

Lyotard would refer to a “crisis of narratives,” in which “the narrative function is losing its functors, its great hero, its great dangers, its great voyages, its great goal.” Narrative, under the postmodern conditions of information societies, is “dispersed in clouds of narrative language elements—narrative, but also denotative, prescriptive, descriptive, and so on” (xxiv). But already in 1966, Genette was writing about the “end of narrative.” In “Frontières du récit,” also published in the narratology issue of Communications, Genette asks where the boundaries of narrative might lie. Is narrative really a ubiquitous, all-encompassing phenomenon, something totally naturalized and even epistemically privileged in human societies? (“It is simply there, like life itself,” says Barthes [1977, 79].) How can we address it without determining where it ends? Where are the thresholds that distinguish narrative from non-narrative forms? Genette will suggest that narrative has both internal and external boundaries that increasingly seem to threaten its integrity as a universal, natural, transhistorical organization.

He first addresses the classical distinction in Plato and Aristotle between diegesis (narrative) and mimesis (imitation), which he decides is not applicable to modern literature (because it is without oral performance). Examining the distinction between narrative and description, Genette proposes that modern literature is in fact almost entirely narrative, with description as a kind of enclave, an internal space that can occasionally be distinguished from the events and actions of narration but does not break out of narrative entirely. It creates a mixture. (This is because for modern literature there is no “rigorous synchronicity” between the succession of text and the events it relates, as there is in the oral reading of a dialogue, for instance [7].) Description is not really one of narrative’s major modes, but must be considered “more modestly as one of its aspects” (8). Even this tentative distinction between narrative and description, Genette insists, is a rather recent development—in European literature, description gradually begins to appear within narrative in an “evolution of narrative forms” by which the proliferation of “ornamental” and later “signifying” description merely “reinforces the narrative’s domination (at least until the beginning of the twentieth century)” (6). We may find this periodization somewhat problematic, but Genette’s point is that the “narrative-descriptive unit” has undergone change, and might be, at some point, broken (7).

It is finally the external boundary of narrative, the “vague murmur” of discourse, ongoing and ambient, without closure, without narrators, which Genette recognizes as the source of a potential break. Discourse, not narrative, is “the natural mode of language, the broadest and most universal mode, by definition open to all forms” (11). Narrative is a particular form, a particular codec, as it were. Genette concludes: “Perhaps narrative, in the negative singularity that we have attributed to it, is, like art for Hegel, already for us a thing of the past which we must hasten to consider as it passes away, before it has completely deserted our horizon” (12).

In Metaphilosophy, published in 1965, Henri Lefebvre critiques structuralism’s predilection for claims like these. He makes the association between “structuralist activity” and the “cybernetic rationality” of automata, information theory, and digital computers explicit (179). Lefebvre observes “the dawn of a ‘worldview’ based on a linkage between structural linguistics, information and communications theory, and perception theory” (179). The philosophy of this worldview, for Lefebvre, is structuralism. “Structuralist activity,” he writes, “is thus always bound up with a technology. It combines two fundamental operations: dissection (into discrete units, atoms of meaning) and arrangement [agencement].” (Lefebvre is glossing Barthes’s characterization in “The Structuralist Activity,” published two years prior.) “The structural man,” therefore, “is the man of technology and technicity” (173). The terms technology and technicity do not appear in Barthes’s essay, but it is clear to Lefebvre that the structuralist activity is a technique: the encoding and decoding of messages, as described in information theory and communications engineering. The real—the object of analysis—is an information source, discretized so that it can be regenerated. For Lefebvre, this makes structuralism essentially computational: it “separates, divides, classifies (into genres and kinds), formal differences, paradigms, conjunctions and disjunctions, binary oppositions, questions that is answers by a ‘yes’ or a ‘no’” (176). It is a digital philosophy, like that of Gottfried Leibniz or Ramon Llull, an ars combinatoria which would suppose that all beings can be constructed from the combination of zeroes and ones.

Lefebvre’s fundamental anxiety—and this may be typical of critiques of both structuralism and of cybernetics—has to do with the apparent abolition of the narration of history. Structuralism, which is for Lefebvre the philosophy of technocratic management, seems to imply a “liquidation of the historical.” With the “cybernetizing of society,” there is no longer any future in the historical sense. “We would enter a kind of eternal present, probably very monotonous and boring, that of machines, combinations, arrangements and permutations of given elements” (178). Temporality itself “disappears into that of entropy . . . Along with time, it is history that disappears in the world, or acquires a new aspect, opening onto a kind of technological temporality without history, or with its only history that of combinations between technological operations” (179).

But history is not only a succession of contents; it is also a succession of forms, and a succession of cultural techniques that produce forms. The structuralists were aware of their position within a modernity in which certain techniques impressed these forms upon them, the forms that populate their own analyses: tables, trees, formulas, IBM punchcards, filing cabinets, index cards, games. These are the media of structuralism by which midcentury thinkers began to conceive narrative as subordinate to databases, a conception which today seems quite prophetic. Even if we accept a thesis like Lefebvre’s (that structuralism is the expression of an annihilation of historical time), to reject structuralist thought undialectically, or at least without viewing it as a moment that the human sciences must pass through, would itself be an ahistorical decision. Frederic Jameson’s assessment from 1972 still resonates:

To say, in short, that synchronic systems cannot deal in any adequate conceptual way with temporal phenomena is not to say that we do not emerge from them with a heightened sense of the mystery of diachrony itself. We have tended to take temporality for granted; where everything is historical, the idea of history itself has seemed to empty of content. Perhaps that is, indeed, the ultimate propadeutic value of the linguistic [and here we might add computational] model: to renew our fascination with the seeds of time. (xi)

Structuralist narratology’s “digitization” of narratives was a response to a digitization already in progress in post-industrial societies. That the mainstream of our culture continues to be characterized by increasingly automated recombinations of elements from massive databases, by statistical methods that generate, classify, and order the “content” that makes up so much of consumption today, only underscores the propadeutic value of the structuralist moment, now more than half a century old.

References

Barthes, Roland. 1961. “Le Centre d’études des communications de masse (le CECMAS),” Annales. Histoire, Sciences sociales 16(5): 991–992.

———. (1963) 1972. “The Structuralist Activity.” Pp. 213–220 in Critical Essays, translated by Richard Howard. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

———. (1966) 1977. “Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narratives.” Pp. 79–124 in Image Music Text, translated by Stephen Heath. New York: Hill and Wang.

———. 1985. The Semiotic Challenge, translated by Richard Miller. New York: Hill and Wang.

Bremond, Claude. (1966) 1980. “The Logic of Narrative Possibilities [La logique des possibles narratifs],” translated by Elaine D. Cancalon. “On Narrative and Narratives: II.” New Literary History 11 (3), 387–411.

Bowker, Geof. 1993. “How to Be Universal: Some Cybernetic Strategies, 1943–70.” Social Studies of Science 23 (1): 107–127.

Eco, Umberto. (1965) 1984. “Narrative Structures in Fleming [James Bond: une combinatoire narrative],” translated by R. A. Downie. Pp. 144–172 in The Role of the Reader: Explorations in the Semiotics of Texts. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Genette, Gérard. (1966) 1976. “Boundaries of Narrative [Frontières du récit],” translated by Ann Levonas. New Literary History 8 (1): 1–13.

———. (1972) 1980. Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method, translated by Jane E. Lewin. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Geoghegan, Bernard Dionysius. 2023. Code: From Information Theory to French Theory. Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press.

Jameson, Fredric. 1972. The Prison-House of Language. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kline, Ronald R. 2015. The Cybernetics Moment: Or Why We Call Our Age the Information Age.

Knuth, Donald. (1968) 1997. The Art of Computer Programming, Vol. 1: Fundamental Algorithms. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Addison-Wesley.

Lefebvre, Henri. (1965) 2016. Metaphilosophy. London and New York: Verso Books.

Lyotard, Jean-François. 1979. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Manovich, Lev. 2001. The Language of New Media. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

1966. “Recherches sémiologiques : l’analyse structurale du récit [Semiological Research: The Structural Analysis of Narrative].” Communications 8.

Rosenbluth, Arturo, Norbert Wiener, and Julian Bigelow. 1943. “Behavior, Purpose and Teleology.” Philosophy of Science 10 (1): 18–24.

Shannon, Claude and Warren Weaver. 1948. The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Urbana, IL: The University of Illinois Press.

Wiener, Norbert. 1948. Cybernetics. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Narrative/Database redux

It seems common and at the same time exceedingly difficult to make historical claims about the role of narrative in cultures: not only to to classify the kinds of narratives that circulate within and shape a given culture, but also to establish what constitutes narrative activity itself, to judge its relative importance in that culture’s (self-)understanding against other modes of knowledge, and to furnish an explanation for any changes in its status. Jean-François Lyotard’s Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge (1979) attempts something like this: it registers a “crisis of narratives,” and asserts, in an “extreme” but memorable simplification, that the “postmodern condition” is characterized by an “incredulity toward metanarratives” (xxiv). What Lyotard observes in the post-Marxist, post-structuralist French university is a situation in which “the narrative function is losing its functors, its great hero, its great dangers, its great voyages, its great goal.” The narrative function here is airborne, atmospheric, “dispersed in clouds of narrative language elements—narrative, but also denotative, prescriptive, descriptive, and so on” (xxiv). Patchy language games are figured (and disfigured) as word clouds, as “clouds of sociality,” masses of linguistic particles, whose edges are indistinct and whose commensurability is minimal. For Lyotard, traditional knowledge takes narrative form; the new cloudiness, on the other hand, is the result of a critical confrontation with scientific knowledge, which has always existed in a state of competition and conflict with narrative knowledge. Narrative knowledge is not strictly compatible with scientific knowledge—they are incommensurate language games—and yet the two are necessarily interlinked and in a way interdependent. There is a “return of the narrative in the non-narrative” (27).

Lyotard was already narrating such transformations in knowledge as effects of “information-processing”; he refers to post-WWII modes of bureaucratic and technocratic thinking associated with early processes of digitization: informatics and information theory, systems theory and cybernetics. The burgeoning “computerized societies,” Lyotard writes, are societies through which the “nature of knowledge cannot survive unchanged” (3–4). Lyotard believes that this change will essentially have to do with a crisis of legitimation of narrative knowledge in which narrators and narratees become subjects of vast (and often privately controlled and managed) “data banks” from which it is only ever possible to generate “little narratives” with “local determination” (60).

Around two decades later, once a significant amount of “information-processing” had moved from mainframes to networked personal computers, it became possible to speak of “new media” and “computer culture,” and to evaluate their effects on narrative culture. In The Language of New Media (2002), Lev Manovich makes a distinction that resonates with Lyotard’s: not between narrative and science, but between narrative and database. Manovich, I think, actually relies on Lyotard’s work more than he cites him, providing updates to many of the latter’s key insights. Manovich’s understanding is that narratives and databases may be regarded as “symbolic forms” (following Ervin Panofsky’s history of perspective) that may have more or less prominence in an age, and from the perspective of the late nineties and early aughts, it seemed that databases were supplanting narratives. Databases and narratives are “natural enemies” (225): narratives are stories with beginnings and ends, and with actors who cause, experience, and reflect upon events, while databases, on the other hand, are structured collections of data that can be traversed in a number of ways, only one of which might be narrative (which is “just one method of accessing data among many” [220]).

New media objects like websites, apps, and video games are often databases first, and narratives second (if at all). Using the vocabulary of Saussurean semiology, Manovich claims that they reverse the relationship of syntagm and paradigm. In semiology, the aim was to derive paradigms (or “codes”) which were virtually present in languages, myths, and other syntagmatic utterances (what Saussure called parole). With new media technologies—effects libraries, menus of commands, stock assets, digital games—it is the paradigms which are given, and the syntagmatic dimension which is virtual. “The complete paradigm is present before the user, its elements neatly arranged in a menu” (231). The inscription of paradigms in digital memory can be understood as the technological a priori that conditions much of the transmedia storytelling described by Henry Jenkins, for example, in which world-building and asset management leads, and narrative follows. The convergent logic of the computer, Manovich’s “universal media machine,” becomes the logic of culture at large (236).

Manovich is actually slightly unclear when it comes to the question of medium specificity and media determination—he prefers to think of database/narrative forms outside of any correlation with specific media technologies (“as two competing imaginations, two basic creative impulses, two essential responses to the world” [233]) but a few pages later asserts that the database form is “inherent to new media,” with the digital computer as its “perfect medium” (237, 234). In any case, Manovich gives a number of examples of works in various media—cinema, photography, art—in which the database impulse takes precedence, and in which any temporal succession is detached from a narrating subject or narrative actors, making narrative implicit at most. In the cinema of Peter Greenaway or Dziga Vertov, we are presented with catalogs of events, in which database procedures like sorting and and linking are foregrounded. Greenaway’s work in particular demonstrates quite well how cinematic narrative may be minimally wrapped around around databases ordered by simple algorithms. In Vertical Features Remake (1978), The Falls (1980), The Draughtsman’s Contract (1982), A Zed & Two Noughts (1985), Drowning By Numbers (1988), Prospero’s Books (1991), and other films, narrative persists, but it is subsumed by database operations that exceed it, namely counting and re-sequencing. “Old media” like cinema are particularly adept at registering or transcoding the effects of “new media,” just as “new media” are always incorporating and simulating, to different degrees, features of “old media.”

It is important to think culture algorithmically, as Lyotard had begun to do and as Manovich continues to do, while also being sensitive to the ways in which “pre-digital” objects—and not only Vertov’s cinema and structuralist cultural theory—already made use of databases and algorithms. I find Manovich’s identification of cinema as a database medium to be useful, given outsized influence in twentieth-century media ecology, but I think that the starting point of this media-theoretical narration—as Wolfgang Ernst and other media archaeologists have recognized—can always be moved further and further backward. A wider media-historical scope may provide new perspectives on the fractured, cloudy media landscape of today’s algorithmic culture, which in many ways has surpassed the imaginations of both Lyotard and Manovich.

References

Ernst, Wolfgang. 2013. Digital Memory and the Archive. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Jenkins, Henry. 2006. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: NYU Press.

Lyotard, Jean-François. 1979. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Manovich, Lev. 2001. The Language of New Media. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Stephen Willats, Social Resource Project for Tennis Clubs (1972)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Utopian typography

Barbara Fuchs and Philip S. Palmer, "A Lettered Utopia: Printed Alphabets and the Material Republic of Letters," Renaissance Quarterly 73 (4): 1235 - 1276

4 notes

·

View notes