Text

In honour of April fools day, let me tell you about Swedish herrings

What does this have to do with april fools? Or linguistics?

Well, if you trick someone with an aprilskämt (april joke) you simply get to call them a stupid herring!

There's a traditional verse which goes like this and is done in a singsong voice when you reveal someone got pranked:

April, april din dumma sill, jag kan lura dig vart jag vill

In English: April, April you stupid herring, I can trick you (to) wherever I want

And pronounciation: [aprɪl aprɪl dɪn dɵma sɪl jɑː kan lʉ̟ːra dej vaʈ jɑː vɪl] (not a true phonetic transcription, I didn't want to do stress or long consonants)

For those of you who don't know IPA, the important thing is that april is pronounced more like app-ril than ay-pril which means it rhymes with sill (herring) and vill (want). It's also not capitalised.

Next question: why?

Well, swedes love herring. It's the essential traditional holiday food in all sorts of pickled varieties. I ate herring today. But more importantly, it rhymes.

Apparently the rhyme itself might be borrowed from a similar German one "April, April, ich kann dich narren wie ich will" which lacks the herring. But who doesn't want to call others stupid herrings if it rhymes?

French also calls people getting pranked fish, specifically poisson d'avril (april fish, a mackerel). A possible origin is French people giving each other fishes that had gone bad on April 1st, starting the trend of pranks.

What about tricking people to wherever you want? A common aprilskämt used to be tricking people to go to some far off place.

This is my source

I hope you learnt something new about april fools traditions today!

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

In honour of April fools day, let me tell you about Swedish herrings

What does this have to do with april fools? Or linguistics?

Well, if you trick someone with an aprilskämt (april joke) you simply get to call them a stupid herring!

There's a traditional verse which goes like this and is done in a singsong voice when you reveal someone got pranked:

April, april din dumma sill, jag kan lura dig vart jag vill

In English: April, April you stupid herring, I can trick you (to) wherever I want

And pronounciation: [aprɪl aprɪl dɪn dɵma sɪl jɑː kan lʉ̟ːra dej vaʈ jɑː vɪl] (not a true phonetic transcription, I didn't want to do stress or long consonants)

For those of you who don't know IPA, the important thing is that april is pronounced more like app-ril than ay-pril which means it rhymes with sill (herring) and vill (want). It's also not capitalised.

Next question: why?

Well, swedes love herring. It's the essential traditional holiday food in all sorts of pickled varieties. I ate herring today. But more importantly, it rhymes.

Apparently the rhyme itself might be borrowed from a similar German one "April, April, ich kann dich narren wie ich will" which lacks the herring. But who doesn't want to call others stupid herrings if it rhymes?

French also calls people getting pranked fish, specifically poisson d'avril (april fish, a mackerel). A possible origin is French people giving each other fishes that had gone bad on April 1st, starting the trend of pranks.

What about tricking people to wherever you want? A common aprilskämt used to be tricking people to go to some far off place.

This is my source

I hope you learnt something new about april fools traditions today!

48 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi, submitter of многоꙮчитїй here!

uhhhhh. i did NOT expect it to get this far?? i guess the multiocular o is more powerful than i thought. i'm very happy though, duh. ꙮ has been my favorite letter/symbol since i first saw it. im glad other people like it too, and that i was able to show it to people! same goes for all the other words (and signs!!) submitted! this tournament was a really lovely idea. i'm pleased многоꙮчитїй got to be a part of it. i guess i'll leave it there. have a goꙮd day everyone!

also i'm probably never gonna live down saying "i don't think there's a common english word for many-eyed" while staring "multiocular" in the face lol

Some words from the submittor of our winner! Congratulations for submitting the best word

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aaand we have a final result! Congratulations to the winner and thank you to all who participated in submissions and voting

Final round: Haikea vs многоꙮчитїй, mnogoočitii

(poll at the end)

Haikea (Finnish)

[ˈhɑi̯keɑ]

Translation: A feeling of quiet, melancholic, sometimes even mournful longing. "Wistful" comes fairly close as a translation, though it's not exactly the same.

Finnish is an Uralic language belonging to the Finnic branch spoken by 5 300 000 people in Finland, where it is one of two national languages (the other is Swedish though it is less used, Finnish is the main language).

Motivation: It's one of the most beautiful words to say in Finnish, IMO; it has a beautiful flow to the vowels, and it almost sounds like a sigh. It's also an emotion often associated with a lot of Finnish art, literature, music and culture in general, and thus it's a strong part of Finnish identity.

многоꙮчитїй, mnogoočitii (Old Church Slavonic)

IPA not found

Translation: many-eyed

Old Church Slavonic is an extinct language that belonged to the Slavic branch of Indo-European languages. It’s closest related to today’s Macedonian and Bulgarian, but was standardised based on the dialect of Slavs living near 9th century Thessaloniki in today’s Greece by missionaries, who translated Christian literature so they could convert people easier. Old Church Slavonic was then used as the liturgical language of various Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic Churches. A later version of the language called Church Slavonic is still in use in churches today.

Motivation: This particular instance of the word appears once in a manuscript from around 1429. It is the book of psalms, and the word is used in the phrase "серафими многоꙮчитїй," to mean "many-eyed seraphim," as in an angel. the "ꙮ", or multiocular o, is one of my favorite Unicode symbols and also symbols in general. In the next version of Unicode it's going to be updated, because it doesn't even have enough eyes as the original manuscript gave it! Looking past the ꙮ fixation, though, I'm a fan of angels and angelic imagery, as well as eye imagery. A single word for "many-eyed" is really cool to me, since I don't recall there being one in English. It's a useful phrase for more than just angels, like spiders, molluscs...

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Final round: Haikea vs многоꙮчитїй, mnogoočitii

(poll at the end)

Haikea (Finnish)

[ˈhɑi̯keɑ]

Translation: A feeling of quiet, melancholic, sometimes even mournful longing. "Wistful" comes fairly close as a translation, though it's not exactly the same.

Finnish is an Uralic language belonging to the Finnic branch spoken by 5 300 000 people in Finland, where it is one of two national languages (the other is Swedish though it is less used, Finnish is the main language).

Motivation: It's one of the most beautiful words to say in Finnish, IMO; it has a beautiful flow to the vowels, and it almost sounds like a sigh. It's also an emotion often associated with a lot of Finnish art, literature, music and culture in general, and thus it's a strong part of Finnish identity.

многоꙮчитїй, mnogoočitii (Old Church Slavonic)

IPA not found

Translation: many-eyed

Old Church Slavonic is an extinct language that belonged to the Slavic branch of Indo-European languages. It’s closest related to today’s Macedonian and Bulgarian, but was standardised based on the dialect of Slavs living near 9th century Thessaloniki in today’s Greece by missionaries, who translated Christian literature so they could convert people easier. Old Church Slavonic was then used as the liturgical language of various Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic Churches. A later version of the language called Church Slavonic is still in use in churches today.

Motivation: This particular instance of the word appears once in a manuscript from around 1429. It is the book of psalms, and the word is used in the phrase "серафими многоꙮчитїй," to mean "many-eyed seraphim," as in an angel. the "ꙮ", or multiocular o, is one of my favorite Unicode symbols and also symbols in general. In the next version of Unicode it's going to be updated, because it doesn't even have enough eyes as the original manuscript gave it! Looking past the ꙮ fixation, though, I'm a fan of angels and angelic imagery, as well as eye imagery. A single word for "many-eyed" is really cool to me, since I don't recall there being one in English. It's a useful phrase for more than just angels, like spiders, molluscs...

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Final round: Haikea vs многоꙮчитїй, mnogoočitii

(poll at the end)

Haikea (Finnish)

[ˈhɑi̯keɑ]

Translation: A feeling of quiet, melancholic, sometimes even mournful longing. "Wistful" comes fairly close as a translation, though it's not exactly the same.

Finnish is an Uralic language belonging to the Finnic branch spoken by 5 300 000 people in Finland, where it is one of two national languages (the other is Swedish though it is less used, Finnish is the main language).

Motivation: It's one of the most beautiful words to say in Finnish, IMO; it has a beautiful flow to the vowels, and it almost sounds like a sigh. It's also an emotion often associated with a lot of Finnish art, literature, music and culture in general, and thus it's a strong part of Finnish identity.

многоꙮчитїй, mnogoočitii (Old Church Slavonic)

IPA not found

Translation: many-eyed

Old Church Slavonic is an extinct language that belonged to the Slavic branch of Indo-European languages. It’s closest related to today’s Macedonian and Bulgarian, but was standardised based on the dialect of Slavs living near 9th century Thessaloniki in today’s Greece by missionaries, who translated Christian literature so they could convert people easier. Old Church Slavonic was then used as the liturgical language of various Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic Churches. A later version of the language called Church Slavonic is still in use in churches today.

Motivation: This particular instance of the word appears once in a manuscript from around 1429. It is the book of psalms, and the word is used in the phrase "серафими многоꙮчитїй," to mean "many-eyed seraphim," as in an angel. the "ꙮ", or multiocular o, is one of my favorite Unicode symbols and also symbols in general. In the next version of Unicode it's going to be updated, because it doesn't even have enough eyes as the original manuscript gave it! Looking past the ꙮ fixation, though, I'm a fan of angels and angelic imagery, as well as eye imagery. A single word for "many-eyed" is really cool to me, since I don't recall there being one in English. It's a useful phrase for more than just angels, like spiders, molluscs...

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why are languages similar to each other?

Let's talk about the way languages are connected to each other!

First, the obvious one...

Language families!

Languages with a common origin form a language family. Language evolves and changes over time, so populations speaking the same language in different places will over hundreds of years form different languages since they evolve in different ways. Now imagine one of those daughter languages splitting again and again... Soon there's a whole family of related but mutually unintelligible languages!

So, are all language families big? And how many are there?

We have two giants with over a thousand languages each: Atlantic-Congo languages and Austronesian languages. Some families have a couple hundred languages, like the famous prototypical examle Indo-European languages. Most families have lots fewer though, only a sixth of all 237 language families contain more than ten languages.

Some languages don't have any relatives and they're called isolates. At present, 184 languages count as isolates, among them Basque and Sandawe.

Some languages are unclassified, as there's too little data to draw conclusions. Family membership is based on comparing cognates, words that have the same origin and whose sound changes can be reconstructed back to the origin (like English 'two', Swedish 'två' and German 'zwei'). It's also common for close relatives to have similar grammar or other features. An example is that Austronesian languages often have fewer consonants.

Language contact!

Two languages meet. What happens? Loans, probably.

Languages borrow things from each other all the time. Words, sounds, grammatical structures and features (like prefixes or suffixes), changing the meaning of something, literally translating words and making up words in the style of another language are all things that happen. Fun loan word facts might be its own post as there's a lot to say about them, for now I only need to establish the fact that language contact probably leads to borrowing stuff and that you can borrow more than words.

Did you know that English didn't have the sound v until it borrowed too many French words with v? Before that, v wasn't recognised as its own sound, just a variant of f that happened sometimes. That's why knives are a thing. Knifes.

There are more levels of similarity due to contact! In areas where languages from different families or different branches from the same family meet and mingle for a long time, they might evolve to become more similar and share some features that might be uncommon globally or uncommon among closer relatives in other areas. These unrelated (or not very closely related) languages share some features, like certain scounds and grammar things. This is called a Sprachbund with a German word. It's possible to say 'linguistic area' or something like that, but it's not as well established and in my opinion sounds worse.

Certain features of a language can also be common in some areas, but not in others. One example is tone; it's very common in sub-saharan Africa and southeastern Asia, but only exists sporadically in other parts of the world. Why? Related languages tend to share features, but language contact definitely plays a role, as unrelated languages have tone. It's language contact!

The point is: Languages that have lots of contact might be similar because of that. Languages are usually influenced both by family origin and by the languages they come into contact with, which makes things interesting.

Onto the last thing I wanted to discuss:

Contact languages!

These arise when speakers of vastly different languages meet and have to communicate, but there isn't a lingua franca. There are two major reasons why this happens: either for commerce or because of slavery or other colonialistic practices.

Anyways, they're pretty interesting! The first kind of contact language that forms is called a pidgin. Its vocabulary is limited and the grammar is simple. There are no native speakers and you can only use it in a few domains (like being able to talk about commerce but not politics).

Now, imagine a community of people speaking this pidgin, made by improvising until something sticks. There are words and a little bit of grammar. Over time it will get a bit more complex, but still no native speakers. Then some of them form families and have children, who grow up speaking the pidgin.

And this is where the magic happens: children have an amazing ability to invent language by making generalisations and improvise until they can speak about anything. There are examples of children deprived of language coming up with entire languages if left alone (like the Deaf school in Nicaragua which tried to teach lip reading and not sign language, but the children came up with a sign language on their own that they started teaching instead). Children will fill in the gaps in the pidgin and give it a more complex structure.

After some time of this the pidgin turns into a creole. The line between them is blurry and unclear, but a creole is a fully realised language that you can speak about anything in, just like all other languages. It also has native speakers.

There's a common way pidgins and creoles are structured: usually one language is used as the base for words, but they're changed and reanalysed to mean something else. This language has often been the colonial power's language: there are a number of English and French based creoles for example.

The grammar on the other hand is usually taken from the other language(s). In the slavery cases, slaves were often taken from many different ethnic groups that might speak similar but mutually unintelligeble languages, or just very different languages, which means that those creoles draw on features from many languages. Of course, words can be based on any of the involved languages, but it's common that one makes up an overwhelming majority. The creoles are still unintelligible for speakers of the language it's based on.

This was all for now! Languages interact with each other in interesting ways and similarities can have many reasons.

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Final round: Haikea vs многоꙮчитїй, mnogoočitii

(poll at the end)

Haikea (Finnish)

[ˈhɑi̯keɑ]

Translation: A feeling of quiet, melancholic, sometimes even mournful longing. "Wistful" comes fairly close as a translation, though it's not exactly the same.

Finnish is an Uralic language belonging to the Finnic branch spoken by 5 300 000 people in Finland, where it is one of two national languages (the other is Swedish though it is less used, Finnish is the main language).

Motivation: It's one of the most beautiful words to say in Finnish, IMO; it has a beautiful flow to the vowels, and it almost sounds like a sigh. It's also an emotion often associated with a lot of Finnish art, literature, music and culture in general, and thus it's a strong part of Finnish identity.

многоꙮчитїй, mnogoočitii (Old Church Slavonic)

IPA not found

Translation: many-eyed

Old Church Slavonic is an extinct language that belonged to the Slavic branch of Indo-European languages. It’s closest related to today’s Macedonian and Bulgarian, but was standardised based on the dialect of Slavs living near 9th century Thessaloniki in today’s Greece by missionaries, who translated Christian literature so they could convert people easier. Old Church Slavonic was then used as the liturgical language of various Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic Churches. A later version of the language called Church Slavonic is still in use in churches today.

Motivation: This particular instance of the word appears once in a manuscript from around 1429. It is the book of psalms, and the word is used in the phrase "серафими многоꙮчитїй," to mean "many-eyed seraphim," as in an angel. the "ꙮ", or multiocular o, is one of my favorite Unicode symbols and also symbols in general. In the next version of Unicode it's going to be updated, because it doesn't even have enough eyes as the original manuscript gave it! Looking past the ꙮ fixation, though, I'm a fan of angels and angelic imagery, as well as eye imagery. A single word for "many-eyed" is really cool to me, since I don't recall there being one in English. It's a useful phrase for more than just angels, like spiders, molluscs...

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

What even is a language?

All tournament words will hava a short text about the language, but since I don't want to simplify until it's misinformation I need to open the can of worms on what a language really is. Join me, I promise the worms are interesting!

So, what makes two languages different from each other?

Think about it for a while. The first thing that comes to mind is probably that people who speak the same language can understand each other, while people who speak different languages can't. This criterion is called mutual intelligibility by linguists. This sounds easy enough, why is there so much post left?

Well, imagine two villages along a river, A and B. They speak slightly different from each other, but can understand each other. Same language, different dialects. Easy.

Now imagine there's a third village called C further up the river, closer to B than A where they speaking a third slightly different variant. The people in B and C understand each other, but speakers in A and C have a harder time and some can hardly understand each other at all. Do the people in A, B and C speak the same language? It would probably still count as one language since all of them mostly understand each other.

Let's make this more complicated! Imagine a village called D even further up the river. The same situation applies here, C and D speakers understand each other without problem, B and D speakers have a harder time and A and D speakers can't understand each other at all. How many languages are there now? Now imagine we add villages E, F, G etc and apply the same logic. Not so easy anymore

This situation is called a dialect continuum, where different dialects form a continuum so that people understand their neighbours but not all parts of the continuum. This is a common situation where linguists have to try and group languages together out of dialects based on which ones are the most similar.

Fun fact! This does not only happen on a village to village basis, but over larger regions. There is one hiding in plain sight right in the middle of Europe called the Continental West Germanic dialect continuum. There's more about it in the posts with German words, but in short: German is/was a few generation back two (or three) separate languages, the continuum also includes Dutch and "dialects" from Switzerland and Austria. Yet there is a Standard German based on one dialect. Anyway, on with the show.

Language exposure is another interesting worm in this can. Do people understand each other because their languages are similar enough or because they've learned another language? Imagine town X, where a language is spoken, and village Y outside the town. People from Y trade with X and often visit X, since it's a lot bigger. They understand people in X. People from X however, have no clue what people from Y are saying. This isn't mutual intelligibility since it only goes one way, but it will be relevant later on.

Using only mutual intelligibility gives us 6500 spoken languages in the world, as well as 200 signed ones.

This way of defining languages seems too complicated. Can't we just ask people what they speak instead?

Well, you can. This is another way of defining a language: What the people speaking it say is a language is a language. Easy.

On first look this seems reasonable. People know what their language is and will tell us where to draw the lines in the dialect continuum mess. This is the sociopolitical approach to language.

No. This approach intersects interestingly with the mutual intelligibility approach in that the number of languages suddenly skyrockets! There is no estimation, but people tend to call their own community a separate language from the neighbouring communities, even though they all understand each other.

Sometimes these peoples agree that they speak the same language if presented with the mutual intelligibility approach, there just aren't any words for the shared language. Then we can easily go ahead and call them dialects of a shared language.

But what if they just don't like each other and don't want to call what they're speaking the same language, even when they absolutely do? Or when there are political reasons for wanting to differentiate what their dialects, like connecting dialects to separare nation-states? Maybe these political divisions cause dialects to grow further apart, or different writing norms are implemented. Maybe it just happens as land is divided into countries with different policies and influences and a language community is split.

So if mutual intelligibility and people's own classifications don't match, should we just ignore the socio-political part? Often people agree that they speak the same language and let themselves be classified as such, but at other times it would work worse. The line between language and dialect is blurry and confusing.

Take the case of Swedish and Norwegian: I am Swedish and I can understand some Norwegian. It is also my understanding that people living along the border, particularly further north speak similarly and understand each other even better. Considering mutual intelligibility they could be considered the same language, especially some dialects. There is no animosity between Swedish and Norwegian (unlike Swedish and Danish, which might be considered in the same group except the differences are larger?). There are different spelling norms and probably different loan words/influences from countries that have been in contact with Sweden and Norway. Most important of all, it would still feel weird to call them the same language because of the nation-state connection and national identity.

Sometimes, this goes the other way around. Remember town X and village Y? What if the people in Y consider themselves speakers of X, while the people in X still can't understand them? Would it be the same language or not?

Another situation is the national state that really wants everyone to speak the same language. I have another example from Swedish, which is the former dialect Älvdalska (possibly anglisised as Övdalian?) which isn't mutually intelligible with Swedish. Still, for a long time it was considered a dialect anyway, but not anymore. It's its own language.

So what do we do?

Neither approach works on its own since things will get weird if we just pick one. The two big databases over language, ethnologue and glottolog, use a mix: It is mostly based on mutual intelligibility because that's more important for linguistics, but with some sociopolitics where it's reasonable. This leaves between 7100 (ethnologue) and 7700 languages (glottolog), both numbers including sign languages. See how the databases have vastly different numbers? Yeah.

Another fun fact: There are still languages previously unknown to linguists discovered every year. Some are dialects reclassified as languages and some are dying languages spoken only by older generations that were previously missed, as they aren't often spoken.

Anyways, thank you for reading, I hope you enjoyed discovering that everything is more complicated than you think. There will be more posts like this to come. Also, to have it in the post: this knowledge comes from me studying linguistics and being very excited about it

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

What's the average language like?

This will be a giant of a post, because this is a subject that I really like. So much of what we think about language just isn't true when you look at the majority of them and I'm not even going into how the languages themselves are constructed, only the people speaking them, if that makes sense. It will make sense in a moment, I promise

First, let's discuss assumptions. When you think of the abstract idea of a language, what do you imagine?

How many speakers?

Where is it spoken geographically?

Do speakers of the language only speak that language or do they speak at least one other language? How many more languages?

Is the language tied to a state/country?

Is the language thriving or endangered?

In what domains is the language used? (home, school, higher education, administration and politics, in the workplace, in popular media...)

Is the language well documented and supported? Are there resources like dictionaries to look up words in, does google translate work for it, does Word/google docs work etc?

Is the language spoken or signed?

Is the language written down? Is it written down in a standardised way?

Do you see where I'm going with this? My perspective on what a language is has completely shifted after studying some linguistics, and this only covers language usage and spread, not how words and grammar work in different languages. Anyways, let's talk facts. (if no other sources are given the source is my uni lectures)

How many speakers does the average language have?

The median language has 7 600 native speakers.

7 600 people is the median number of speakers. Half the world's languages have more, half have less.

Most languages in this tournament have millions of speakers. But maybe that's relatively common? After all, half of the world's languages have more than 7 600 speakers. No.

94% of all languages have less than a million speakers.

Just so you know, big languages are far from the norm. There are 6700-6800 living languages in the world (according to ethnologue and glottolog, the two big language databases. I've taken the numbers for languages having a non-zero number of speakers and not being classed as extinct respectively. Both list more languages).

6% of 6700-6800 languages would be around 400 languages with more than a million speakers. Still a lot, but only a (loud) minority. It's enough to skew the average number of speakers per language upwards though. Counting 8 billion people and 6800 languages, that's almost 1.2 million people per language on average. The minority is Very loud.

Where are most languages spoken?

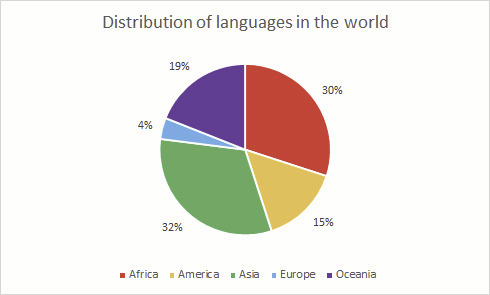

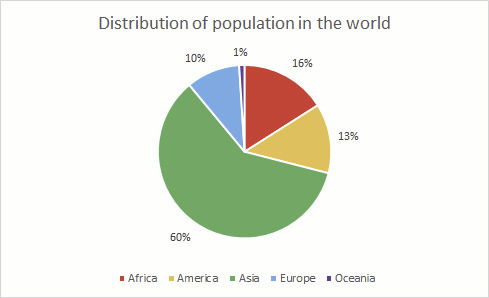

First of all, I'll present you with these graphs (data stolen from my professor's powerpoint) which I first showed in this post:

49% of all languages are spoken in Africa and Oceania, a disproportionately large amount compared to their population. On the other hand, Europe and Asia have disproportionally few languages, though Asia still has the largest amount of languages. Curious, considering Europe is often thought of as a place with many languages.

Sub-Saharan Africa is a very linguistically interesting place, but we need to talk about New Guinea. One island with 6.4 million people. Somehow over 800 languages. If you count the surrounding islands that's 7.1 million people and 1050 languages. Keep in mind that there are 6700-6800 languages in the world, so those 1050 make up more than a seventh of all languages. The average New Guinean language has less than 3000 speakers. Some are larger, but still less than 250 000 speakers. Remember, this is a seventh of all languages. It's a lot more common than the millions of speakers situation!

So yeah, many languages both in and outside New Guinea are spoken by few people in one or a few villages. Which is to say a small territory. But 7600 speakers spread over a big territory will have a hard time keeping their contact and language alive, so it's not surprising.

Moving on, lets talk about...

Bilingualism! Or multilingualism!

Is it common to speak two or more languages? Yes, it is. This is the situation in most of the world and has been the case historically. Fun fact: monolingual areas are uncommon historically and states which have become monolingual became so relatively recently.

One common thing is to learn a lingua franca in addition to your native language, a language that most people in the area know at least some of so you can use it to communicate with people speaking other languages than you.

As an example, I'm writing this in English which isn't my native language and some of you reading this won't have English as your native language either. Other examples are Swahili in large parts of eastern Africa and Tok Pisin in Papua New Guinea (the autonomous state, not the entire island).

Speakers of minority languages often have to learn the majority language in the country too. It's difficult to live somewhere where most daily life takes place in one language without speaking at least some of it. This is the case for native people in colonised countries, immigrants and smaller ethnic groups just to mention a few situations. All countries don't have majority languages, but some are larger, more influential and used for things like administration, business and higher education. It's common for schooling to transition from local languages to a larger language or lingua franca in countries with many languages.

Another approach than the lingua franca is learning the language of villages or towns surrounding you, which is very common in New Guinea and certainly other parts of the world too. It's not unusual to know multiple languages, in some places in sub-saharan Africa people speak five or six languages on a village level. Monolingualism is a weird outlier.

Speaking of monolingualism, let's move on to...

Languages and countries

This is a big talking point, mostly because it affected my view of language before I started thinking about it. First of all, I'm going to talk about the nation state and how it impacts languages within it and the way people view language (mostly because it's a source of misconceptions which fall apart as soon as you start to think about them, but if you don't the misconceptions will stay). Then I'll move on to countries with lots of languages and what happens there instead.

So, the nation state

The idea is that the people of a nation state share a common culture, history, values and other such things, the most important here being language. We can all agree that this type of nationalism has done lots of harm to various minorities and migrants all over the world, but it's still an idea that has had and still has a big impact on especially the western world. The section on nation states will focus on the West, because that's the area I know enough about to feel comfortable writing about in this regard.

How do you see this in common conceptions of language? It's in statements and thoughts like this: In France people speak French (but what about Breton? Basque? Corsican? Various Arabics? Some of the other 15 indigenous and 18 non-indigenous languages established in France? What about people speaking French outside of France?), in the US people speak English (but what about the 197 living indigenous languages? Or the 34 established non-indigenous languages? And the many extinct indigenous languages forcibly killed by the promotion of English?).

In X country people speak X, except for the people who don't, but let's ignore them and pretend everyone speaks X. Which most might actually do if it's the single national language that's used everywhere, it's common to learn a second language after all.

This is of course a simplified (and eurocentric) picture, as many countries either have multiple national languages or recognise at least some minority languages and give them legal protection and rights to access certain services in their languages (like government agency information). Bi-/multilingual signage is common and getting more common, either on a regional or a national level. Maybe because we're finally getting ready to move on from one language, one people, one state and give indigenous languages the minimum of availability they need to survive.

I wrote a long section about how nation states affect language, but I realised that veered way off topic and should be its own post. The short version is that a language might become more standardised simply by being tied to a country and more mobility among the population leading to less prominent dialects. There's also been (and still is) lots of opression and attempts to wipe out minority (often indigenous) languages in the name of national unity. Lots of atrocities have been comitted. Sometimes the same processes of language loss happen without force, just by economic pressure and misconceptions about bilingualism.

What does this have to do with the average language?

I simply want to challenge two assumptions:

That all languages are these big national languages tied to a country

That it's common that only one language is spoken within a country. If you look closer there will be smaller languages, often indigenous and often endangered. There are also countries in the West where multiple languages hold equal or similar status (just look at Switzerland and its four official languages)

Starting with the second point, let's take a look at how Europe is weird about language again

Majority languges aren't universal

I'm going to present you with a list of the 10 countries with the most living languages, not counting immigrant languages (list taken from wikipedia, which has Ethnologue as the source):

Papua New Guinea, 840 languages

Indonesia, 707 languages

Nigeria, 517 languages

India, 447 languages

China, 302 languages

Mexico, 287 languages

Cameroon, 274 languages

Australia, 226 languages

United states, 219 languages

Brazil, 217 languages

DR Congo, 212 languages

Philippines, 183 languages

Malaysia, 133 languages

Chad, 130 languages

Tanzania, 125 languages

This further challenges the idea of one country one language. Usually there's a lingua franca, but it's not always a native language and it's not always the case that most are monolingual in it (like the US or Australia, both of which have non-indigenous languages as widespread lingua francas). Europe is the outlier here. People might use multiple languages in their day to day lives, which are spoken by a varying number of people.

In some cases the indigenous or smaller local languages are extremely disadvantaged compared to one official language (think the US, Australia and China), while in other places like Nigeria, several larger languages are widely used in their respective areas alongside local languages, with English as the official language even though it's spoken by few people.

It's actually pretty common in decolonised countries to use the colonial language as an official language to avoid favoring one ethnic group and their language over others. Others simply don't have an official language, while South Africa's strategy is having 12 official languages (there are 20 living indigenous languages and 11 non-indigenous languages in total, and one of the official ones is English, so not all languages are official with this strategy either). Indonesia handled decolonisation by picking a smaller language (a dialect of Malay spoken by around 10% at the time, avoiding favouring the Javanese aka the dominating ethnic group by picking their language), modifying it, and started using it as the new national language Indonesian. It's doing very well, but at the cost of many smaller languages.

Going back to the list, it's also interesting to compare the mean speaker number (if every language in a country was spoken by the same amount of people) and the median speaker number (half have more speakers, half have less). The median is always lower than the mean, often by a lot. This means that the languages in a country don't have similar speaker numbers, so one or a few languages with lots of speakers drive the average upwards while the majority of languages are small. Just like for the entire world.

The US and Australia stand out with 12 and 10 median speakers, respectively. About 110 languages in the US have 12 or fewer native speakers. The corresponding number for Australia is 113 languages with 10 or fewer speakers. There are some stable languages with few speakers documented, but they have/had between 40 and 60 speakers, so those numbers point towards a lot of indigenous languages dying very soon unless revitalisation efforts succeed quickly. This brings us to the topic of...

Endangered languages

This is an interesting tool called glottoscope made by Glottolog which you can play around with and view data on endangered languages and description status (which is the next heading).

I'll pull out some numbers for you:

Remember those 6700 languages in Glottolog? That's living languages. How many extinct languages are listed?

936 extinct languages. That's ~12,5% of the languages we know of. (Glottolog doesn't include reconstructed languages like Proto-Indo-European, only languages where we either have enough remaining texts to conclude it was a separate language or reliable account(s) that conclude the same. We can only assume that there are thousands of undocumented languages hiding in history that we'll never know of)

How many more are on the way to become extinct?

Well, only 36% (2800 languages) aren't threatened, which means that the other 64% are either extinct or facing different levels of threat

What makes a language threatened? The short answer is people not speaking the language, especially when it's not passed down to younger generations. The long answer of why that happens comes later.

306 languages are listed as nearly extinct and 412 more as moribound. That means that only the grandparent generation and older speak it and the chain of transmission to younger generations has broken. These two categories include 9,26% of all known languages.

The rest of all languages either fall into the threatened or shifting category. The threatened category means that the language is used by all generations but is losing speakers. The shifting category refers to languages where the parental generation speaks the language but their children don't. In both of these cases it's easier to revive the language, since parents can speak to the children at home instead of having to rely on external structures (for example classes in the heritage language taught like foreign language classes in schools).

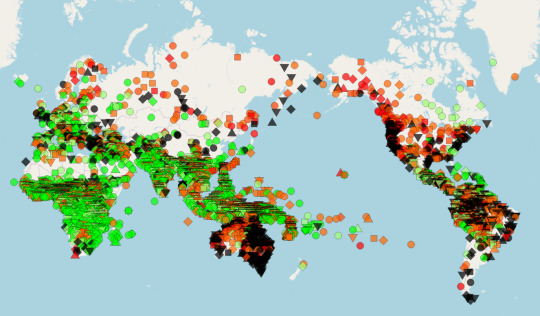

Where are languages threatened?

This map is also from glottoscope and can be found here. I recommend playing around with it, you can zoom in and hover over every dot to see which language it represents. The colours signify threat level: green for not threatened, light green for threatened, orange for shifting, red for moribound and nearly extinct, and black for extinct. I'll come back to the shapes later.

As you can see, language death is more common in certain areas, like Australia, Siberia, North America and the Amazon, but it's still spread over the entire world.

Why are languages going extinct?

There are two important dimensions to the vigorousness of a language: The first is the number of speakers who claim the language as their own and speak it with each other. No speakers means no language. If all speakers move to different places or assimilate by shifting to a dominant language in the area (sometimes for work opportunities or for their childrens' future work opportunities. Sometimes because of which language(s) schools are taught in or disinterest from the children in the language and culture. Sometimes migration of an ethnic group for various reasons leads to language shifts. There are many complex reasons to why the link of transmission can break)

The other dimension, which ties into the first one, is the number of situations in which a language is used. There are many domains a language can be used in, like at home, in school, in the workplace, in politics and administration, in higher education, for international communication, in religious activities, in popular media like movies and music etc. When a language is no longer or never used in a particular domain, it might lose the associated vocabulary. When it becomes confined to a singular domain like the home, the usage goes down. The home is usually the last place an endangered language is spoken.

Usage in a domain is a reason to speak or hear the language. It's a reason to keep it alive. People also forget or get worse at languages they don't use. That's why a common revitalisation tactic is producing movies, radio programmes, news reporting, books and other media in a dying language. It gives people both reason and opportunity to use their language skills. Which language is used in schools is also important, as it keeps basic vocabulary for sciences and explaining the world alive. Another revitalisation tactic is making up new words to talk about modern concepts, some examples are the Kaqchikel word rub'eyna'oj from this tournament or creating advanced math vocabulary in Māori.

What does endangered languages have to do with the average language?

Trying to get this post back on track, these are some key points:

64% of all documented languages are either extinct or facing some level of threat. That's the majority of all language

Even excluding the extinct languages, the majority of languages are threatened or worse

This means that the average language is facing a loss of speakers, some more disastrous than others. Being a minority language in an increasingly globalized world is dangerous

Describing a language

Are you able to look up words from your native language in a thesaurus or a dictionary? What about figuring out how a certain piece of grammar works if you're unsure? Maybe you don't need that for your native language, but what about a second language you're learning?

If your native language is English, there are lots of resources, like online and book dictionaries/thesauruses or an extensive grammar (a book about how English grammar works). There's also a plethora of websites and courses to learn English, and large collections of written text or transcribed speech. If a linguist wants to know something about the English language there's an abundance of material. If someone wants to learn English it's easy and courses are offered in most parts of the world.

For other languages, the only published thing might be a list of 20 words and their translation into English or another lingua franca.

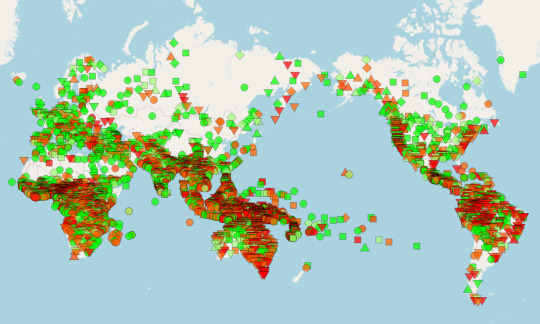

Let's take a look at the same map as earlier, but toggled to show documentation status in colour and endangerment status with shapes:

Here, the green signifies a long grammar and the light green a grammar. Both are extensive descriptions of the grammar in a language, but they differ in length. A long grammar has to contain over 300 pages and a grammar over 150. Orange is another type of grammar, namely a grammar sketch. Those are brief overviews of the main grammatical features or features that may be of interest for linguists, typically between 20 and 50 pages. The purpose isn't to be a complete grammar, only a starting point.

The red dots can signify a lot of things, but what they have in common is that there's no extensive description of the grammar. In those cases, the best description of the language might be a list of which sounds it contains, a paper about a specific feature, a collection of texts or recordings, a dictionary, a wordlist (much shorter than dictionaries) or just a mention that it exists.

Why are grammars and descriptions even important?

The better described a language is, the easier it is to learn it and study it. For a community facing language loss, it might be helpful to have a pedagogical grammar or a dictionary to help teach the language to new generation. If the language becomes extinct people might still be able to learn and revive it from the documentation (like current efforts with Manx). It also makes sure unique words or grammatical features as well as knowledge encoded in the language isn't lost even if the language is. It's a way of preserving language, both for research and later learning.

What's an average amount of descripion then?

36,2% of all documented languages have either a grammar or a long grammar. That's pretty good actually

38,2% of all documented languages would be marked by a red dot on this map, meaning that more languages than that don't have any kind of grammar at all, maybe only as little as a short list of words

The remaining 25,6% have a grammar sketch

So as you see, the well documented languages are in minority. On the brighter side, linguists are working hard at describing languages and if they keep going at the same rate as they have since the 1950s, they'll reach the maximum level of description by 2084. Progress!

Tying into both description of languages and domains where language is used...

What about technology and language?

There are many digital tools for language. Translation services, spelling and grammar checks in word processors, unicode characters for different scripts and more. I'm going to focus on the first two:

Did you know that there are only 133 languages on google translate? 103 more are in the process of being added, but that's still a tiny percentage of all languages. As in 2% right now and 3,5% once these other languages are added going with the 6700 language estimation.

Of course, this is for the most part a limination with translation technology. You need translated texts containing millions of words to train the algorithms on and the majority of languages don't have that much written text, let alone translated into English. The low number still surprised me.

There are 106 official language packs for Windows 10 and I counted 260 writing standards you can use for spelling checks in Word. Most were separate languages, but lots were different ways to write the same language, like US or British English. That's a vanishingly small amount. But then again:

Do all languages have a written standard?

No. That much is clear. But how many do? I'll just quote Ethnologue on this:

"The exact number of unwritten languages is hard to determine. Ethnologue (25th edition) has data to indicate that of the currently listed 7,168 living languages, 4,178 have a developed writing system. We don't always know, however, if the existing writing systems are widely used. That is, while an alphabet may exist there may not be very many people who are literate and actually using the alphabet. The remaining 2,990 are likely unwritten."

(note that Ethnologue classes 334 languages without speakers as living, since their definition of living language is having a function for a contemporary language community. I think that's a bad definition and that means it differs from figures earlier in the post)

Spoken vs signed

My last point about average languages is about signed languages, because they're just as much of a language as spoken ones. One common misconception is that signed languages reflect or mimic the spoken language in the area, but they don't. Grammar works differently and some similarities in metaphor might be the only thing the signed language has in common with spoken language in the area.

Another common misconception is that there's only one sign language and that all signers understand each other. That's false, signed languages are just as different from each other as spoken languages, except for some tendencies regarding similarity between certain signs which often mimic an action (signs for eating are similar in many unrelated sign languages for example).

Glottolog lists 141 Deaf sign languages and 76 Rural sign languages, which are the two types of signed language that become entire languages. The difference is in reach.

Rural signs originate in villages with a critical amount of deaf people (around 6) that make up a fully fledged language with complete grammar to communicate. Often large parts of the village learn tha language as well. There are probably more than 76, that's just the ones the linguist community knows of.

What's called Deaf sign languages became a thing in the 1750s when a French guy named Charles-Michel de l'Épóe systematised and built onto a rural sign from Paris to create a national sign language which was then taught in deaf schools for all deaf children in France. Other countries took after the deaf school model and now there's 141 deaf sign languages, each connected to a different country. Much easier to count than spoken languages.

Many were made from scratch (probably building on some rural sign), but some countries recruited teachers from other countries that already had a natinonal sign language and learnt that instead. Of course they changed over time and with influence from children's local signs or home signs (rudimentary signs to communicate with hearing family, not complete languages), so now there's sign language families! The largest one unsurprisingly comes from LSF (Langue des Signes Française, the French one) and has 63 members, among them ASL.

What does this have to do with average languages? Well, languages don't have to be spoken, they can be signed instead. Even if they make up a small share of languages, we shouldn't forget them.

Now for some final words

Thank you for reading this far! I hope you found this interesting and have learned something new! Languages are exciting and this doesn't even go inte the nitty gritty of how different languages can be in their grammar, sounds and vocabulary. Lots of this seem self evident if you think about it, but I remember how someone pointing out facts like this truly shifted my perspective on what the language situation in the world truly looks like. The average language is a lot smaller and diffrerent from the common idea of a language I had before.

Please reblog this post if you liked it. I spent lots of time writing it because I'm passionate about this subject, but I'd love if it spread past my followers

#linguistics fun fact time!#anyways can't believe this is finally done#i was going to make a series with informative posts between each round#and look what happened#i spent all my time writing this instead#hope you enjoyed!#and check out the linguistics fun facts tag#there are some more posts like this#linguistics

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Final round: Haikea vs многоꙮчитїй, mnogoočitii

(poll at the end)

Haikea (Finnish)

[ˈhɑi̯keɑ]

Translation: A feeling of quiet, melancholic, sometimes even mournful longing. "Wistful" comes fairly close as a translation, though it's not exactly the same.

Finnish is an Uralic language belonging to the Finnic branch spoken by 5 300 000 people in Finland, where it is one of two national languages (the other is Swedish though it is less used, Finnish is the main language).

Motivation: It's one of the most beautiful words to say in Finnish, IMO; it has a beautiful flow to the vowels, and it almost sounds like a sigh. It's also an emotion often associated with a lot of Finnish art, literature, music and culture in general, and thus it's a strong part of Finnish identity.

многоꙮчитїй, mnogoočitii (Old Church Slavonic)

IPA not found

Translation: many-eyed

Old Church Slavonic is an extinct language that belonged to the Slavic branch of Indo-European languages. It’s closest related to today’s Macedonian and Bulgarian, but was standardised based on the dialect of Slavs living near 9th century Thessaloniki in today’s Greece by missionaries, who translated Christian literature so they could convert people easier. Old Church Slavonic was then used as the liturgical language of various Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic Churches. A later version of the language called Church Slavonic is still in use in churches today.

Motivation: This particular instance of the word appears once in a manuscript from around 1429. It is the book of psalms, and the word is used in the phrase "серафими многоꙮчитїй," to mean "many-eyed seraphim," as in an angel. the "ꙮ", or multiocular o, is one of my favorite Unicode symbols and also symbols in general. In the next version of Unicode it's going to be updated, because it doesn't even have enough eyes as the original manuscript gave it! Looking past the ꙮ fixation, though, I'm a fan of angels and angelic imagery, as well as eye imagery. A single word for "many-eyed" is really cool to me, since I don't recall there being one in English. It's a useful phrase for more than just angels, like spiders, molluscs...

#best non english word tournament#final round#finnish#old church slavonic#haikea#mnogoočitii#good luck and have fun voting

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

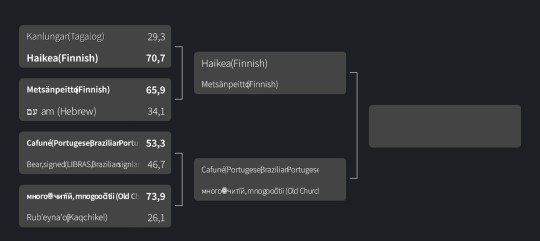

It's finally time for the final round!

Yes, it is true. I've stopped procastinating on this tournament long enough to give us the thrilling resolution and award the title of best non-English word. To celebrate, I'll post both the final poll, as well as a monster of a post about languages that I've been working on since at least August. So there's lots to look forward to!

Now, onto the contestants...

As we see, the final competitors for best word will be haikea and многоꙮчитїй/mnogoočitii.

Haikea won the Finnish showdown and now reigns the supreme Finnish word in a pretty close match, while многоꙮчитїй crushed its opponent cafuné by virtue of multiocular o (I presume). So now we'll see: will the multiocular o be enough to best the mighty power of Finnish tumblr and its melancholic feelings?

We'll only know in a week

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Semifinals: Cafuné vs многоꙮчитїй, mnogoočitii

(poll at the end)

Cafuné (Portuguese, Brazilian Portugese)

Portugal: [kɐ.fuˈnɛ] Brazil: [ka.fuˈnɛ]

Translation: The act of running your fingers through someone's hair in a tender way, usually massaging or gently scratching their scalp

Portuguese is an Indo-European language belonging to the Romance branch originating from Portugal. Due to colonialism it is the main and official language of Brazil, where 213 million of its 264 million speakers live. Brazilian Portuguese is considered a dialect of Portuguese as they are mutually intelligible.

Motivation 1: It can be platonic! It can be romantic! It's a cute thing!

Motivation 2: vsjsh affection....... 💞💞 it’s a very sweet gesture it’s very nice and comforting and makes you feel safe

Note: There were two submissions for this word, one in each dialect. Since it’s the same word but with slight pronunciation differences they will compete together

многоꙮчитїй, mnogoočitii (Old Church Slavonic)

IPA not found

Translation: many-eyed

Old Church Slavonic is an extinct language that belonged to the Slavic branch of Indo-European languages. It’s closest related to today’s Macedonian and Bulgarian, but was standardised based on the dialect of Slavs living near 9th century Thessaloniki in today’s Greece by missionaries, who translated Christian literature so they could convert people easier. Old Church Slavonic was then used as the liturgical language of various Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic Churches. A later version of the language called Church Slavonic is still in use in churches today.

Motivation: This particular instance of the word appears once in a manuscript from around 1429. It is the book of psalms, and the word is used in the phrase "серафими многоꙮчитїй," to mean "many-eyed seraphim," as in an angel. the "ꙮ", or multiocular o, is one of my favorite Unicode symbols and also symbols in general. In the next version of Unicode it's going to be updated, because it doesn't even have enough eyes as the original manuscript gave it! Looking past the ꙮ fixation, though, I'm a fan of angels and angelic imagery, as well as eye imagery. A single word for "many-eyed" is really cool to me, since I don't recall there being one in English. It's a useful phrase for more than just angels, like spiders, molluscs...

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Semifinals: Haikea vs Metsänpeitto

(poll at the end)

Haikea (Finnish)

[ˈhɑi̯keɑ]

Translation: A feeling of quiet, melancholic, sometimes even mournful longing. "Wistful" comes fairly close as a translation, though it's not exactly the same.

Finnish is an Uralic language belonging to the Finnic branch spoken by 5 300 000 people in Finland, where it is one of two national languages (the other is Swedish though it is less used, Finnish is the main language).

Motivation: It's one of the most beautiful words to say in Finnish, IMO; it has a beautiful flow to the vowels, and it almost sounds like a sigh. It's also an emotion often associated with a lot of Finnish art, literature, music and culture in general, and thus it's a strong part of Finnish identity.

Metsänpeitto (Finnish)

[ˈmetsænˌpei̯tːo]

Translation: Getting lost in a forest in a way that one suddenly no longer recognizes the terrain around them and becomes invisible to others (according to mythology).

Finnish is an Uralic language belonging to the Finnic branch spoken by 5 300 000 people in Finland, where it is one of two national languages (the other is Swedish though it is less used, Finnish is the main language).

Motivation: I love that there's a word for this concept! And (like almost all Finnish words) it sounds beautiful.

Note: It’s a compound of metsän and peitto meaning forest and blanket/cover(age)

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Semifinals: Haikea vs Metsänpeitto

(poll at the end)

Haikea (Finnish)

[ˈhɑi̯keɑ]

Translation: A feeling of quiet, melancholic, sometimes even mournful longing. "Wistful" comes fairly close as a translation, though it's not exactly the same.

Finnish is an Uralic language belonging to the Finnic branch spoken by 5 300 000 people in Finland, where it is one of two national languages (the other is Swedish though it is less used, Finnish is the main language).

Motivation: It's one of the most beautiful words to say in Finnish, IMO; it has a beautiful flow to the vowels, and it almost sounds like a sigh. It's also an emotion often associated with a lot of Finnish art, literature, music and culture in general, and thus it's a strong part of Finnish identity.

Metsänpeitto (Finnish)

[ˈmetsænˌpei̯tːo]

Translation: Getting lost in a forest in a way that one suddenly no longer recognizes the terrain around them and becomes invisible to others (according to mythology).

Finnish is an Uralic language belonging to the Finnic branch spoken by 5 300 000 people in Finland, where it is one of two national languages (the other is Swedish though it is less used, Finnish is the main language).

Motivation: I love that there's a word for this concept! And (like almost all Finnish words) it sounds beautiful.

Note: It’s a compound of metsän and peitto meaning forest and blanket/cover(age)

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Semifinals: Cafuné vs многоꙮчитїй, mnogoočitii

(poll at the end)

Cafuné (Portuguese, Brazilian Portugese)

Portugal: [kɐ.fuˈnɛ] Brazil: [ka.fuˈnɛ]

Translation: The act of running your fingers through someone's hair in a tender way, usually massaging or gently scratching their scalp

Portuguese is an Indo-European language belonging to the Romance branch originating from Portugal. Due to colonialism it is the main and official language of Brazil, where 213 million of its 264 million speakers live. Brazilian Portuguese is considered a dialect of Portuguese as they are mutually intelligible.

Motivation 1: It can be platonic! It can be romantic! It's a cute thing!

Motivation 2: vsjsh affection....... 💞💞 it’s a very sweet gesture it’s very nice and comforting and makes you feel safe

Note: There were two submissions for this word, one in each dialect. Since it’s the same word but with slight pronunciation differences they will compete together

многоꙮчитїй, mnogoočitii (Old Church Slavonic)

IPA not found

Translation: many-eyed

Old Church Slavonic is an extinct language that belonged to the Slavic branch of Indo-European languages. It’s closest related to today’s Macedonian and Bulgarian, but was standardised based on the dialect of Slavs living near 9th century Thessaloniki in today’s Greece by missionaries, who translated Christian literature so they could convert people easier. Old Church Slavonic was then used as the liturgical language of various Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic Churches. A later version of the language called Church Slavonic is still in use in churches today.

Motivation: This particular instance of the word appears once in a manuscript from around 1429. It is the book of psalms, and the word is used in the phrase "серафими многоꙮчитїй," to mean "many-eyed seraphim," as in an angel. the "ꙮ", or multiocular o, is one of my favorite Unicode symbols and also symbols in general. In the next version of Unicode it's going to be updated, because it doesn't even have enough eyes as the original manuscript gave it! Looking past the ꙮ fixation, though, I'm a fan of angels and angelic imagery, as well as eye imagery. A single word for "many-eyed" is really cool to me, since I don't recall there being one in English. It's a useful phrase for more than just angels, like spiders, molluscs...

#best non english word tournament#poll time#semifinals#brazilian portugese#portugese#cafuné#old church slavonic#mnogoočitii

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's time for semifinals!

Don't worry, I haven't abandoned this tournament, I've just been very busy. Anyways, we're down to the final four:

As we see, both Finnish words did well in round four but now we'll finally see which one is the best: Haikea or metsänpeitto.

It seems you guys really like the multiocular o in многоꙮчитїй/ mnogoočitii as well, but the race between cafuné and bear in LIBRAS was a lot closer with cafuné winning. Let's see if it makes it to the final too, or if it'll be defeated by Old Church Slavonic.

We're getting close now!

Polls will be posted tonight, make sure to propagate for your favorite word!

17 notes

·

View notes