Text

Epilogue

Buster never came quietly into the house except when he was unhappy, and to her satisfaction he’d been very noisy of late. She’d hear him a mile away, whistling a tune or yelling at Elmer to let the chickens alone. Tonight he clomped through the door, banging it behind him, in full, off-key voice.

“Oh, we ain’t got dough, no-whoa-whoa,

There ain’t no paint on the bungalow,

What of it?

We love it!”

She stifled a giggle.

“Where are you Nellie Dean?” he called.

“In here,” she said, laughing.

His eyebrows popped when he walked through the bedroom door. “Yellow,” he said, looking around.

“Yellow,” she stated firmly, running the brush along the edge of the crown moulding.

He ambled over and slid a hand up her stockinged calf. She painted a stripe beneath the line she’d drawn under the crown moulding. “If I didn’t know better, I’d think you were trying to distract me.” She shifted her weight on the ladder.

“Just steadying you,” he said innocently, looking up at her.

“And looking up my skirt.”

He shrugged. “You expect me not to?”

“I expect nothing of the sort.” She painted another stripe.

“Why yellow?”

“It’s for boys and girls. I thought June and Violet might object to blue, and you know Bobby and Jimmy would riot if we went for pink.”

“Surprised you want to be up there after painting sets all day yesterday.”

“Well, their train comes in on Monday. I thought I’d get it ready for them.”

“Why not tomorrow? Or Sunday?” The hand on her calf stroked.

“Practice tomorrow night, remember? And I have to work on my lines Sunday. We open two weeks from today.” She handed the paint bucket down to him. “I’m going to let the first coat dry.”

Buster set the bucket down and helped her off the ladder, though she didn’t need his assistance.

“Still leaves tomorrow morning and afternoon,” he said, putting his arms about her waist and pecking her forehead.

She put her arms around him in kind and looked at him meaningfully. “Maybe I have plans then that don’t involve painting.”

“Oh?”

“How was filming today?” she said. He wasn’t the only one who could play stupid.

He grumbled. “The less said the better.”

It was, she knew, the worst picture they’d given him yet.

Sometimes they’d talk long into the night about the logistics of opening his own film company, what kind of films he’d make and how he’d fashion a new studio. It was an empty dream. Buster figured he could scratch together a team of writers, prop man, costume man, and other salary men, maybe even pay Gabe enough to peel him away from M-G-M, but the big problem was the sound equipment. And he did want sound, just not the constant corny jokes M-G-M insisted on sticking him with. The equipment would cost millions he didn’t have, though, and even if he could afford it, he had never solved the dilemma of who would distribute the films. Still, they both dreamed.

“I’m sorry.” She leaned in and kissed him.

He returned the kiss with fervor.

“Careful, I might get paint on you,” she said, feeling a little breathless despite herself.

He kissed her out the door toward their bedroom.

“The oven’s going to go off any minute,” she said.

“Hmm,” Buster said.

“You don’t want a burned dinner.”

“Hmm.”

She extricated herself from his arms with a parting kiss to his cheek and he whined. “Don’t pout,” she said, as she headed down the hall and to the kitchen. “I told you I have plans tomorrow morning and afternoon.”

“What about tonight?” he said, following.

She looked at the oven timer, saw that only two minutes remained on the dial, and cracked the door. The leg of lamb was brown and glistening, but she judged that it needed a slightly browner tone. She closed the door and set the timer for another ten minutes. “Almost done. You have just enough time to feed the chickens while I set the table. If you help me put the second coat of paint on later, we can talk about tonight.”

He laughed. “You’re a cruel mistress.”

“Mistress?” she said, raising an eyebrow, but she was teasing.

He kissed the tip of her nose. “It’s only a saying, Mrs. Keaton.”

“Go feed the chickens, Mr. Keaton,” she said, and gave his behind a swat as he walked away.

She could hear him singing as she pulled the china out of the cabinets.

“We wear old clothes, we wear old shoes,

We don’t eat nothin’ but Irish stews,

What of it?

We love it!”

Notes: Thank you sincerely to everyone who read and enjoyed this story, and to savageandwise for beta-ing a few chapters when I was a little stuck.

In real life, of course, Buster met and married the gorgeous Eleanor Norris who remained his soulmate until he died, so people might rightfully ask, 'Why rewrite history?'

Well, for many of us female Buster fans, we see the unhappy parts of this beautiful man's life between 1928 and 1933--his alcoholism, his crumbling marriage, the loss of his independence as an actor and filmmaker--and can't help but wish for a better outcome for him.

To be honest, I'm not exactly sure what first compelled me to begin writing this story--and when I began writing I thought it would be a story, not a 150,000-word novel! Buster was a pleasant diversion as the second wave of the pandemic rolled through in late 2020 and I had a vague idea of him having a romantic fling with a girl around the time he lost his studio, but I had not fully realized Nelly as a character yet when I began writing the story. I wasn't even sure if they would sleep together. The story became an exploration of what might have unfolded if Buster had encountered a woman he liked as much as Eleanor in these earlier years. In an odd way, I guess, it was my way of giving that somewhat broken man all those years ago a little bit of happiness.

Not that he was entirely unhappy during those years. As much as he chafed against the MGM films he was obligated to make, they were financially lucrative and he was a very popular star. Obviously money and popularity don't equal happiness, but it seems at first like things weren't all bad for him. I happen to think that his alcoholism didn't really take a hard grip on him until the early 1930s, even though in my story the drinking is a problem as early as mid-1927.

One thing I feel confident of:

Buster simply did not want to leave his marriage. Even though Natalie didn't satisfy his sexual needs after Bobby was born, he loved her and wanted to stay with her. I don't think he knew how to express that he wanted their marriage to last or communicate with her about the other problems (her apparent lack of interest in his career, for example, or his tendency to act foolish and embarrass her), hence the drinking and acting out. You'll note that in this story he never makes a move to leave Natalie for Nelly.

Along the way, I grew fonder of Nelly and more invested in her own modest dreams. Just like Buster, she eventually has to accept that the career she wants is not within reach and make do with something else. I liked writing her family and following her as she grew. She's not a self-insert. I'm not an actor. I definitely don't have a large bosom or beautiful brunette tresses. ;)

If you have any other questions about the story or my writing process, feel free to ask. I will likely write some Buster Keaton one-shots in the future, but for now I have about a million other writing projects to finish--on top of a 74,000-word X-Files fic I'd really like to finish. If you have requests for any particular Buster stories, I will consider them.

Thanks again reading, leaving comments, and providing input! I'm glad that such an obscure fandom gave so many people joy.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 44

The rain came, not a sprinkle but a deluge worthy of Steamboat, and he watched the edifices in his life collapse around him.

First came his marriage. The divorce was just as bad as he’d expected. The flashbulbs went off in his face like fireworks and he couldn’t face court without half a bottle of whiskey to settle his nerves before his arrival every day. He handed Natalie the Villa without a fight, as well as alimony, maintenance for Bobby and Jimmy, and money for a downpayment on a house on the coast as she waited for a buyer for the Villa. It was over with faster that way, and he was apathetic toward the money and the home. There would always be more and another. He did take one bit of Nelly’s advice and insisted he keep the boys on weekends. The court granted this to him, much to the displeasure of the four Talmadge women.

And if he didn’t see much of the boys afterwards, dropping them off at Victoria Avenue with his ma, Louise, and Jingles instead, perhaps he could be forgiven. Parties, premieres, and bridge games still dominated Saturday and Sunday evenings, but more than that there was the aching need to forget, which overruled all else. He could be happy and carefree as long as a bottle was nearby. He could even brush off his financial losses when the market crashed in October, though his financial advisor soberly pointed to numbers and told him that he was all but penniless on paper.

The toboggan was in free fall by then, anyway.

Taking pity on him with the divorce (but foremost satisfied with the profits from The Cameraman and Spite Marriage) M-G-M had given him a whole year off from pictures, and he didn’t know what to do with himself. Film had been his only constant for over ten years. He waited to hit the bottom of the slope, but didn’t. Whenever he felt himself beginning to care about the shambles he was making of his life, he drank all the more.

Nineteen twenty-nine passed like a cruel stranger in the night and then came a fresh new decade for him to screw up. Dorothy got tired of waiting for him to marry her and found a fiancé. The suits at M-G-M gave him the New Year’s Gift of his first talkie, but it was irredeemable swill, though nothing could convince them that it was all wrong for him. That made it easier to show up late or, some days, not show up at all. He was reprimanded in the severest terms.

He didn’t care.

The girls at the bungalow came and went.

When Free and Easy turned out to be a hit, it was worse than if it had been a flop. He knew that he’d never get to make a film his way again; all that the suits had to do was point to the money and the argument was over.

His world shrunk down to the forgetting. He told himself what every drunk told himself, that he could get it under control if he wanted to. He just didn’t want to.

Then it was the day before Christmas, and he attempted a tricky pratfall at the studio party while corked out of his mind.

When he came to, it was in his mother’s bed, his cottony mouth tasting of a sewer and his head throbbing as if it had been fractured with a hammer. When he looked in the bureau mirror, he saw that his aching bottom lip was split down the middle and there was dried blood on his chin and in an aching spot at the crown of his head. He was as thirsty as if he had been wandering the desert for thirty days. His worried-looking ma informed him it was the day after Christmas.

“Don’t drink tonight,” she begged. “Give it a rest, just tonight.”

As much as he objected to the idea, he was too weak and weary to wander far from bed. She brought in a tray with a bowl of chicken broth, a plate of toast, and a mug of black coffee. She spoon fed him the broth as if he were four years old again, and when he’d finished eating he wept on her shoulder.

He had a single glass of bourbon that night and slept like the dead. The next day, she suggested seeing a picture for a distraction. It was Saturday and King of Jazz was playing at Grauman’s.

The film opened—or rather, a giant book on a stage opened—to Paul Whiteman’s fat, simpering face, and he was flung back to the Villa on a May evening. Nelly was dressed in purple, cutting a rug with the blue-eyed singer from the orchestra, and he was surrounded by all his friends in his palace.

He stood up and walked straight out. Before his ma could stop him, he was in a taxi heading back to the bungalow. All he could think about was having a drink.

Myra had been there, or someone who had heard about the episode at the Christmas party, for there wasn’t a single bottle in sight.

For a moment, he considered taking the baseball bat to the empty glass bookshelves again, which had, years ago, been inexplicably replaced. Instead, like a madman, like the desperate drunk he was, he turned the place upside-down looking for a flask. He was certain to find one hidden somewhere, and he did.

But not before finding a piece of steno paper.

At first he didn’t know what it was, then recollection dawned. He’d been there before, Ashbury Avenue in Evanston, Illinois.

He sat down at the table and had a restorative pull of whiskey before taking up a pencil.

It’s been two years. Are you still waiting?

He folded the paper, slid it in an envelope, licked a stamp, and put the flag up on the mailbox. Within an hour, the letter was as forgotten as his troubles.

He didn’t discover the return letter until three weeks later. It was buried in mash notes and other fan letters, and was postmarked the week before. As soon as he saw the return address, his heart thudded.

I don’t have a beau, the reply said. Are you asking?

He went into a shop that sold records that very same day. He listened to various songs on a phonograph in the corner, the clerk made patient by the honor of having a celebrity in his store. At last, he chose one by Meyer Davis’s Swanee Syncopators.

“You ship?” he asked the clerk. When the answer was yes, he said, “Good. I’ve got an address in Illinois for you.”

“This one is a few years old. 1928,” said the clerk, making small talk as Buster handed over a piece of paper with the address written on it.

“Is that right?” he said. “Well, then it’s perfect. That’s the year I met her.”

“Who?”

“My old girl.” He read the label of the record out loud just in case there was any doubt. “ ‘My Old Girl’s My New Girl Now.’ ”

Note: Penultimate chapter, Buster Kittens. Thank you for being on this journey with me and enjoying this very niche fan fiction.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is me, astonished. Last night I finished "That's My Weakness Now."

I will plan to post the two final chapters between this weekend and next.

As always, if you've enjoyed this story, please comment, share, or tell your friends. I'm feeling pretty wistful that it's done!

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 43

Buster awoke unpleasantly the next morning. His chest burned and his head hurt so much, his skull felt like it was cracked. His nose was completely stopped up. He remembered the night before and sat up like a whip had been laid across his body. At first, he didn’t see Nelly anywhere in the room and had the absurd thought that the previous night had been a fever dream. His heart hammered in his chest.

“Nelly?” he said.

Only then did he notice her folded up in the chair, which she had dragged in a corner by the window. The curtains were drawn, but she was using a sliver of light to read a newspaper. She said something as she straightened up and laid the newspaper aside, maybe, “Oh you’re awake.” She came over and sat on the edge of the bed and laid a cool hand on his forehead, then frowned.

“What?” he said. A cough wracked him and he shut his eyes involuntarily, holding up his elbow to shield Nelly from it. When he opened them again, she was holding the hotel stationery out to him.

You might have the flu.

“Might,” he said. His own voice—deepened by the illness and the morning—was distant in his congested ears. He judged that his hearing was slightly improved from the previous day, though not enough that he could hear anything but the faintest trace of a murmur from Nelly.

She frowned and moved his hair off of his forehead so she could feel it again and he was struck by how he’d missed her fussing over him. It felt good, but it was the only thing that did.

On top of the flu or cold or whatever it was, he had a savage hangover; that was the headache and the queasiness that filled him from top to bottom. He hadn’t had a drink since before the play and his nerves screamed for one now. His spirits were also as black as they’d ever been as his drowsiness cleared and his circumstances reasserted themselves. It was as though he’d been dumped at the bottom of a deep earthen pit with no way to scale the walls and could only just make out a small circle of light at the mouth. He could feel himself riding a crest of panic and groped for his cigarettes on the bedside table.

Nelly stood and he looked over his shoulder to see her bend over a tea tray on a cart. Her stockings and dress were back on, her hair pinned back up and make-up reordered. It made him regret that he’d only gotten a few minutes of her in her chemise with her hair down before they’d both fallen into a dead sleep. She returned with a black cup of coffee.

He felt so woozy and ill for a moment that he had to close his eyes. “I’ve gotta have a drink or I’ll puke,” he said.

Rather than frowning at him as he expected, she passed him the stationery. Where is it?

“The booze?” he said. He’d slid a bottle of whiskey in one sock and a bottle of bourbon in the other and put both in his satchel, creating a cocoon of underclothes and other garments to protect them. “Smaller bag. Wrapped ‘em in socks.”

She nodded and momentarily disappeared, then returned with the bourbon. He unscrewed the lid with a shaky hand and dumped enough in that the coffee rose to the rim of the cup. She took the bottle as he took a drink. He swallowed as much of the bitter combination as he could stand and set the saucer and cup on the bedside table, then lit his first cigarette of the day. She set the bottle at her feet and picked up the paper and pen.

I could tell you’ve been drinking a lot.

He almost asked her how, but decided it was probably obvious enough and shrugged. He knew she didn’t like it. “I can handle it,” he said, coughing after taking a drag.

She looked skeptical, but didn’t object. He finished the coffee and cigarette and she fussed over him more, stroking his hair and rubbing his back.

What do you want for breakfast? she wrote.

He thought about it and decided something heavy sounded good. “Steak and eggs,” he said. “Medium, eggs over easy.”

She nodded. Breakfast came and he ate in bed in his pajamas with the tray on his lap, though he could barely taste the food with his nose so congested. Nelly had two slices of toast and an orange juice. The nausea was gone for the time being and his headache was beginning to ease, but only just. The curtains remained drawn, which he appreciated, and Nelly had turned on a bedside lamp. He ate his fill, smoked another cigarette, had more coffee and whiskey, and felt a little better. After he’d coughed up what his chest had filled with overnight, his cough seemed to have eased by a few degrees.

After she cleared his tray, she passed him the stationery. I wrote you a letter.

Misery washed over him. He hadn’t really banked on it, but a sliver of him had hoped that they’d already come to some kind of understanding and could avoid further talk. Last night she’d seemed like the old Nelly he remembered, but in the daylight she had a kind of poise that was new. It was the poise of someone running her own show.

“Alright,” he said, resigned.

He sat on the edge of the bed and she sat next to him, her hands clasped between her knees.

Dearest Buster, went the letter, and he knew then that he wasn’t going to like what was coming.

I woke up early this morning & I’ve done a lot of thinking about what comes next. It would be much easier to tell you everything if you could hear me, but I will try my best to explain with this letter.

The night before my birthday when you gave your big party with Paul Whiteman, I saw you dancing with Natalie & I realized that you loved her. You don’t have to pretend you don’t. I don’t know how long you have been married but I have heard that divorce is no easy thing & I am sure you will not get over it overnight. I feel it is the right & sensible thing to give you time to heal from it. I can hear you saying now in that indignant way you have, ‘How long is that?’

To that I say at least a year. In my heart of hearts I know it would not be good for either of us if you replaced her with me as soon as the papers are signed. It is too much like putting a tiny bandage on a cut that needs stitches. It will bleed through in no time.

You haven’t asked my opinion about what you should do, but if you did, I would tell you to go back to California & face things head-on. I don’t for a minute think you are serious (or if you are you shouldn’t be) about letting her keep your house & your children. You must fight for the things you want. Also, you have a very good deal with M-G-M & you ought to return before they give you the sack. You don’t want to lose what you have worked so hard for. Maybe it isn’t the same as having your own studio but you seemed to get on very well with Snap Shots & I hope you are getting along just as well with your new picture.

I can’t help but think that you may be happy without me once the divorce is well & truly behind you. As you read this now, you are tired, sick, & depressed & you don’t know where to turn. I’m as good as anything. It must not feel like it now, but this pain will pass. On the other side, you may not be the slightest bit interested in a small time stage actress. (I have accepted that I am not going to be in pictures & the theater is the next best thing for me.) I hope I am wrong but I am trying to be realistic.

If a year passes & you find you still feel for me, then I will return to California to be with you. I will not hold you to any promises now. You may drink & have dalliances & whatever you must do to endure your troubles. I can’t make any promises either, but I do know what’s in my heart at this moment. You are in my heart & I couldn’t give a damn about anyone else in the world.

‘Take your share of troubles, take it & don’t complain. If you want the rainbow you must have the rain.’ That’s how the song goes. Well, this is your share of troubles. I may be at the end of the rainbow & I may not. Whatever happens, I am not sorry for our affair & I am glad that it happened.

Truly yours,

Nelly

She didn’t want him. That was all he could think.

He looked up from the letter. “Dontcha love me even a little?”

To his astonishment, Nelly’s expression folded and she burst into tears, covering her face with her hands.

“Ah, hell,” he said. “Don’t cry.” He gathered her into his arms and blinked tears back; he wasn’t happy about blubbering like a baby the night before and didn’t want to repeat the spectacle. Her crying was probably a good sign, one that she did care for him as much as he wanted her to, but he couldn’t feel anything but desolate at her decision, like a hungry dog that had shown up at a warm door and been struck away. She clung to him hard and pressed her face into his shoulder.

Eventually he released her to cough. She pulled away and wiped her tears on her skirt.

He looked down at his hands. A sharp urge to uncap the bottle of whiskey came over him. Of course he didn’t want to leave everything he had to Natalie, least of all Bobby and Jimmy, but to struggle against her would take willpower he wasn’t sure he had. He imagined Dutch, Norma, and Peg in the courtroom with Natalie staring daggers into his flesh, saw the reporters thronged outside the courtroom door ready to report his every sneeze, and figured he didn’t stand a chance. The Talmadges would get what they wanted out of him. They always had in the past. Surrender was the fastest way to put everything behind him.

Nelly nudged her paper into his hands. Of course I do, the words read.

His inclination was to keep quiet and bear his hurt silently like he always did. Somehow, though, a self-pitying “it don’t feel like it” slipped out of him.

She slid her hands into his and squeezed, bringing him back to the present, and her lips found his. It was the first time she had kissed him since they’d made up. Suddenly, he wanted her with an agony that threatened to split him in two, but before he could carry the thought further, a cough seized him. When it was over, he found that she had brought over the VapoRub.

“Again?” he said with a groan. “I smell like a sick ward.”

You should. You’re sick, her piece of paper said. As if her point weren’t clear, she frowned at him.

He surrendered, unbuttoning his pajama top and stripping off his undershirt. He put his hand out for the VapoRub, but she shook her head. She took the jar herself and bent down to smear his chest with the cool ointment. Gooseflesh rose on his arms. She was more thorough than he had been, getting both pectorals and rubbing a generous amount of the stinking stuff into the center of his chest.

“Nelly,” he said.

She looked down at him, but didn’t pause in her activity.

“Nelly.”

He grabbed her upper arms, brought her down to him, and crushed his mouth against hers. His fear that she would resist was quickly put to rest. She matched him for ferocity. Soon she was straddling him in the center of the bed, kissing him for dear life.

“I didn’t pack nothing,” he said, breaking the kiss off with a gasp. “I mean …”

She was pulling down his pajama trousers and glanced up long enough to shake her head.

“I’ll stop if you want me to,” he said.

She leaned over him to grab her pen and paper from the table beside the bed. He held onto her waist to steady her, grasping it with an appreciation he hadn’t had before. The shape of her was so solid, real, and familiar, all he’d wanted for months.

Just pull out. Nelly waited long enough for him to read the words, then tore the paper from his hands and returned her mouth to his.

He was no good with words. He’d never be able to tell her the way that memories of her had floated like an undercurrent through his mind in the quiet moments since he’d last seen her and that he was certain that the answer to all his troubles, at least part of it, lay with her. He tried to show it. He kissed her hands. He pressed his lips to the inside of each wrist. And he tried to show it as he made love to her.

Even with long pauses so he could turn away and cough, it was too brief. He spilled onto the bedclothes, trying to avoid the skirt of her dress; they had both decided without saying anything that removing the dress was too much of a bother given the situation’s urgency. When he turned back, he saw the small dark stains of VapoRub on her dress. She noticed them at the same time.

“Oh well,” she mouthed, shrugging.

He pulled her into his arms and held her fast. As the glow of his climax faded, he felt almost feverish. He closed his eyes. She petted his hair.

He knew he hadn’t changed her mind. Even soft in his arms, she exuded a steely resoluteness. He wasn’t sure how long they lay there. Eventually he found his underclothes and put them back on and Nelly tidied herself up.

They sat side by side on the bed again and he smoked a cigarette.

The paper in her hands said, Did you really mean it when you said I was the reason you fell apart?

He coughed as he exhaled a lungful of smoke. “Yes.”

She looked sideways at him and he could see the disbelief in her face. He took another drag from his cigarette. He couldn’t explain what he meant and he didn’t want to, either. The nearest he could sort it out for himself, it was the way she had been the one dependable bright spot as his studio was yanked out from under him and his marriage took a final swan dive, even if he hadn’t realized it until it was too late.

I have to leave, the paper read. The matinee is at 1.

“Okay,” he said.

She took the cigarette from his fingers, put it in the ashtray, and pressed her hands into his. She leaned her head on his shoulder. Desolation descended on him again. He wasn’t sure he was strong enough to endure everything that lay ahead, but silently he promised himself that he would try.

He would try for her sake.

Notes: I know that Buster and Nelly are in a hotel room during this scene, but I felt like the image of the couple in the park was very suggestive of their conversation. I didn't save the citation, so I don't know the artist. Sorry!

Only two chapters to go, Buster Kittens. If you have enjoyed this story, please share it on social media, with fellow Buster fans, etc.

P.S. I didn't actually think Buster and Nelly would make love in this chapter. Had no intentions of writing a sex scene. Their actions somehow suggested it, though, and there we were.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Chapter 42

Saturday night’s performance was the production's finest so far. Everyone was at their witty best, scarcely a line was missed, and when it was it was quickly recovered. Nelly’s back-and-forth with Eugene had never been so snappy. It seemed the audience had never laughed so loud when she fixed him with a withering look and scoffed, “I had rather hear my dog bark at a crow, / Than a man swear he loves me.” The applause at intermission went on and on. In fact, the only disruption was the barking loud cough of a man in the front row. “God help me,” Leo said backstage between scenes, “I’m going to go down there and choke him with a whole bag of lozenges if he keeps it up.”

She was exultant when Eugene grabbed her hand at the end and they walked to the footlights to bow when the curtain went back up. They stepped back to let the others bow, then joined hands with them for a group bow.

Backstage in the dressing room behind a curtain reserved for Hattie, Faye, and her, she exchanged her pale green Elizabethan frock with the pink trim for a long-sleeved mauve dress with generous ribbon-work at the neckline and cuffs that she’d recently bought to stave off the bitter December air. She scrubbed the thick white foundation from her face and powdered her skin down to a more natural shade while Hattie removed her costume and smoked a cigarette. Faye had a date with her boyfriend and left as soon as she had changed. As with the previous two Saturdays, the plan was for the gang to get food at the Green Door and take the El to the Aragon to dance the night away.

“You girls ready yet?” Harry said on the other side of the curtain as Nelly was touching up her lipstick.

“Hold your horses, I still need to get this clown paint off,” said Hattie.

Nelly stood up to let her take her turn at the mirror and stepped out from behind the curtain.

“Beautiful as always, Beatrice,” said Harry, planting a noisy kiss on her cheek.

“Flattering as always, Don Pedro,” she said, but the attention made her feel good. He was still no less boring, but she felt no desire to stop seeing him as long as the play was going well and his companionship was agreeable within bed and without.

The other cast members joined them one by one after transitioning from costumes to ordinary clothes.

“Hattie, you’re taking quite a long time, dear,” Fred called.

“Kiss my ass!” she replied, and they all fell into stitches.

Their jubilance brimmed over into song. “Who’s that coming down the street? Who’s that looking so petite ...?” Harry began singing, slinging his arm around her.

“Who’s that coming down to meet me here?” Fred chimed in. “Who’s that, you know who I mean—”

“Sweetest ‘who’ you’ve ever seen. I could tell her miles away from here,” they sang in tandem, Fred harmonizing.

“Yes, sir! That’s my baby!” Eugene bellowed.

“No, sir! Don’t mean maybe!” John answered, coming down the hall toward them.

“Men,” said Hattie, laughing and buttoning up her coat as she came out from the curtain.

They headed toward the back door in full voice.

“Yes, ma’am! We’ve decided!

No, ma’am, we won’t hide it.

Yes, ma’am, you’re invited now!”

Nelly joined in another chorus just as they spilled out into the alley, her arm around Harry’s waist. “Yes, sir! That’s my baby! No, sir! Don’t mean maybe!”

She glanced right, the briefest of glances, and saw a figure leaning against the bricks just outside the door, holding what appeared to be a bouquet of floors. In the back of her mind, she assumed it must be an admirer of blonde, curly-haired Hattie, who often had to inform ardent male audience members that she was married. Harry saw the figure too and cocked an eyebrow at her.

“Yes, ma’am! We’ve decided!” Nelly sang, turning left along with the others, but something about the figure troubled her. It almost looked like …

She looked back, only intending to satisfy herself that she was being silly. The figure had left the wall and was retreating down the alley.

“No, ma’am ...” Her voice died in her throat. She would know that walk anywhere. She wriggled out from beneath Harry’s arm as quick as an eel, suddenly desperate. “Wait!” she shouted after the figure.

Harry caught her by the elbow. “Hey, what are you doing? Who is that?”

The figure didn’t turn, but rounded the corner and was gone. All else forgotten, she tore her arm away and looked wildly at Harry for a split second. “I think I know who that is. I have to—don’t worry, I’ll catch up. I’ll catch up with you later. Don’t wait for me.”

She dashed down the alley as fast as she could go.

Behind her, Harry yelled, “Wait!” But his footsteps didn’t follow.

She was in serious danger of slipping on the frozen puddles and half-melted humps of snow turned ice in the night air, but her balance held and her heels didn’t give way beneath her. The alley spat her out in the middle of a crowded sidewalk. Despite the frigid temperature, people were out in droves enjoying the nightlife and the storefronts decorated for Christmas. Probably some of them were the playgoers she had just performed for.

She didn’t see the figure and a woebegone lump formed in her throat. She knew it couldn’t really be him; such scenarios only lived in the likes of Norma Talmadge pictures. Still, she stood on tiptoes and scanned left and right, hoping to see the familiar figure in the froth of people.

The lump grew larger with every lost second. All of the men were dressed similarly to the figure in dark overcoats and fedoras. She’d almost resigned herself to turning back around and catching up with the gang when she saw it at some distance walking west.

A cry ripped from her throat. “Buster!”

Everyone around her stared, but the figure, now a good twenty yards or so ahead, walked on. All social graces abandoned, she bumped and clawed people out of the way, gasping, “Excuse me, excuse me!”

It couldn’t be. It couldn’t be.

She was going to lose it. “Buster!”

The figure still did not turn. Gritting her teeth, she picked up speed. It would be a miracle if she didn’t twist her ankle. At long last, she was able to close the gap. The figure was five yards away, now four, and she shouted as loudly as she could manage, “Buster!”

Again, everyone around her stared except the figure.

Two yards now. “Buster!”

The figure kept making its way forward. Finally, finally, she was close enough to lay a hand on its shoulder. It didn’t feel like Buster’s and she realized a split second before the figure turned how foolish she’d been to believe something so impossible.

The sorry was half out of her mouth when the head lifted and there he was, as unmistakable as Will Shakespeare himself.

There was Buster.

“Nelly.” He looked as startled as she felt. His face was tired and the bags beneath his eyes were as pronounced as she’d ever seen them. He held a bouquet of flowers and a playbill in his left hand, and a fedora was pulled low on his forehead.

She almost threw her arms around him, but the impulse disappeared as a blaze of anger seized her. Everything had been going so well. He had no idea what she’d gone through to get where she had, what she’d done to unlove him. Now here he was again, splitting her heart open.

Struggling to master her feelings, she instead said in a calm voice, “How did you find me?”

He smiled sadly and tapped his ear. “Can’t hear. Caught a darn cold on the train.” His voice was stuffy. As if on cue, he coughed into his fist.

“You were the man in the front row who wouldn’t stop coughing!” she said, feeling dumbstruck.

“Hey, lovebirds. Move it,” a man said, glaring at them.

It brought her back to reality and she stepped off the sidewalk. Buster mirrored her. Despite her shouts, no one had taken notice that the Great Stone Face stood among them.

He cleared his throat. “I messed up. I shouldn’t have tried to find you. Look …”

His words made her miserable. Already she never wanted to let him out of her sight again, but here he was telling her it was all a mistake.

“I shouldn’t have bothered you,” he said, doleful. “You don’t need me dragging you down. Everything’s going so good for you. You should forget you ever saw me. Get back to your friends and boyfriend.” He attempted an encouraging smile, but the effect was tragic.

“God dammit!” she exploded. She blinked back tears of anger. “You don’t get to just show up and disappear. I won’t stand for it!”

He winced. “All I caught was ‘god dammit.’ ”

It was bad enough that this confrontation was happening in a public space when she was off her guard, but even worse that he couldn’t hear a damn thing she was saying. She took off her gloves, stuffed them in her pockets, and dug in her handbag for a pencil. She didn’t have any paper, so she took the playbill from Buster’s hand. She folded the front cover over and wrote on the margin of the second page, Where are you staying?

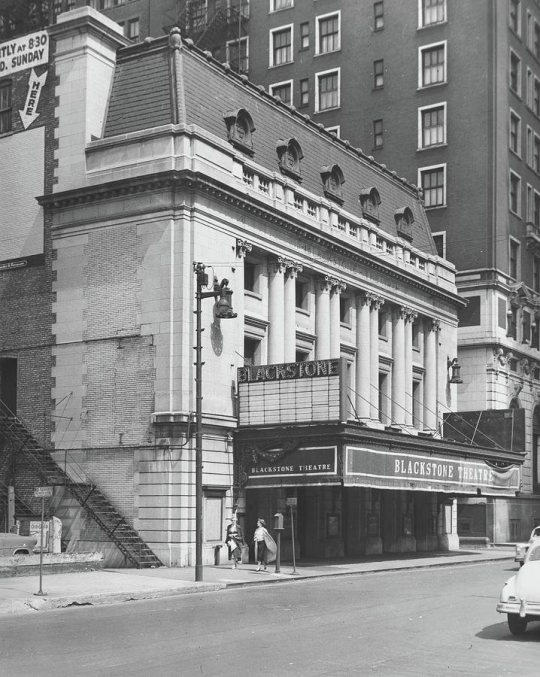

They needed to go somewhere to talk, that much she was convinced of, but Harry knew her room at the Blackstone well and she didn’t want to risk an interruption if he went looking for her.

Buster glanced down at the message, then at her. “The Allerton, but I’m telling you, you oughta forget it. You were heading somewhere and I interrupted your plans. Forget you ever saw me.” He coughed into his elbow for the space of several long moments.

I will hit you if you say that again, she wrote, with a hand that shook with fury as much as the cold.

He read the sentence and looked at her with a wary expression. She was so angry in that instant, she almost wished he would dare her.

“Well, it’s about two miles that way,” he said, pointing north. Another coughing spell seized him.

She gestured for him to follow her to the curb and put out her hand for a taxi. Within a minute, a black-and-yellow car slowed to a stop in front of them. Buster opened the back door for her. “The Allerton,” he said to the driver, getting in beside her.

She settled into the seat as the cab pulled away and the city lights began flashing by. Even if he could have heard her, she wouldn’t have known what to say. She had dreamed for months of meeting him again, but she never truly thought it would happen. For the life of her, she couldn’t remember what she had imagined herself saying to him. Perhaps she was in shock. They spent the short ride in silence save for Buster’s coughing, and the elevator ride up the tenth floor of the hotel was just as quiet. She was keenly aware of his nearness and their mutual discomfort.

She followed him to Room 1013, hanging a few steps behind him. He unlocked the door and they went inside. She stepped ahead of him and he brushed past her after closing the door. The contact made her heart thump and she realized with dismay that her attraction to him hadn’t faded at all.

The room was small, a single rather than a suite. There was a tiny bathroom just inside the door and a double bed, a coat rack, a bureau, a chair, and a table. She watched him turn on the bedside lamp and a floor lamp by the table. His suitcase and satchel sat unopened on the floor and she wondered if he had come straight to the play without changing clothes. The room certainly didn’t look lived in. She remembered the last time they had been in a hotel room, the scant memory of being sick as he held her hair back from the toilet bowl and her subsequent hangover and shame.

“Gotcha these,” he said flatly, almost as an afterthought, turning around. He held out the bouquet but didn’t meet her eyes.

“Oh.” She took the flowers without thinking, then regretted immediately that she had accepted a peace offering. Red roses, pink carnations, and white baby’s breath were clustered within a paper wrap. The cold had mortally wounded the blossoms and they were limp and bruised. Now that the shock of his presence was wearing off, she was beginning to piece together the story. He had come to see her performance and brought her flowers, but she didn’t know how he could have known about the play. “How did you find me?” she said.

“Huh?”

She raised her voice. “How did you f—” and when he still shook his head she set the flowers on the bedside table, went to the table, and found hotel stationery and a pencil.

How did you find me?

He stood next to her and looked down at the paper.

“Had your folks’ address,” he said. She noticed he was still avoiding her eyes. “You gave it to me that day, remember?”

He didn’t have to elaborate on ‘that day.’ The loss was still imprinted in her mind as if it had been yesterday.

Face flushed and heart beating faster, she scribbled, You met my parents? She could only imagine her mother’s shock and flattery upon seeing the star of Steamboat Bill standing on her front porch.

Buster read the words. “Not your parents, your sister,” he said, stuffing his hands in his pockets. “Well, the maid answered first. I asked for you and she brought back your sis. Bawled me out like the devil. Couldn’t hear what she was saying, but she was angrier than I’ve ever seen a girl. Had to explain that I lose my hearing when I get a cold. Finally she storms back inside and throws this playbill at me. Been in pictures long enough to read lips alright. ‘Take it and go,’ she says. Well, I got the hint then. Picked it up and left with my tail between my legs. I was walking away when I saw it was for a Shakespeare play.”

Nelly’s thoughts reeled. She remembered that Ruthie and Gerald had planned to Christmas-shop for the children after picking her up following tomorrow’s matinee performance, so Sunday dinner at their parents’ had been moved up a day. Though she was angry at Buster, she couldn’t imagine bawling him out. She almost apologized for Ruthie’s behavior, but caught herself, feeling that he needed to know that forgiveness could not be gotten so easily, if forgiveness was what he had come for.

She’s protective of me, she wrote.

Buster sighed. “I know. I had it coming.” He turned away, coughing and coughing into his elbow.

Her heart softened just a fraction. I’m going to get something for your throat, she wrote. She sat on the edge of the bed and telephoned for some tea with honey. “Is there a commissary here? My friend is sick,” she said, as Buster continued coughing. When told that there was, she ordered some lozenges and Vick’s VapoRub to be brought up to Room 1013 with the tea.

Buster unbuttoned his coat, draped it on the chair at the table, and set his hat on the bureau. He came and sat next to her, though he left space between them. He pulled his cigarettes from his jacket pocket and lit one. Smoke rose in the air.

“Guess I owe you an explanation,” he said, still not meeting her eyes and sounding as though an explanation was the last thing he wanted to give. He turned his head and coughed.

All she could think of was the feeling of grasping her castmates’ hands and bowing before the glowing hot spotlights. That was what he was taking from her, whether he knew it or not.

To avoid answering, she stood up and unbuttoned her own coat. She laid it atop his and gathered the stationery and pencil. She pulled the Gideon’s Bible from the shelf of the bedside table for a surface to write on and sat back down on the bed.

“You never cut your hair,” he said. He was finally looking at her, a sad smile playing on his lips.

Her heart wrenched and she looked away. He looked ten years older than the last time she’d seen him. It wasn’t just that the bags under his eyes were puffier, the lines in his forehead seemed deeper as well. There was a shadow of stubble on his face. She wondered how much he’d been drinking. He didn’t smell like booze, but something told her he’d been deeply wed to the bottle since she’d left.

She stared at the stationery, struggling to make sense of his presence. Maybe it would have been better if she had let him go and joined back up with the gang.

“I know it ain’t fair to you,” he said, as if reading her thoughts. “As soon as you walked out that door with your friends I knew right then I shouldn’t have bothered you. I’m sorry for that. I shoulda thought of how it’d be for you.” Another coughing fit hit him.

She looked at him and rolled her lips in. He wasn’t wrong.

“Anyway, I guess you probably heard,” he continued, exhaling smoke and clearing his throat. “Nate’s through with me.”

She could only shake her head, stunned. So that was it. The revelation made her feel horrible and sick. He had only sought her out because his wife had left him, not because he’d tried to live without her and couldn’t.

“Really?” he said. “It’s all over the papers.”

I don’t read the gossips anymore, she scrawled. She handed the pad to him.

He read it and looked up. “ ‘Cause of me.”

She nodded, turning away. Her stomach see-sawed.

He sighed. “If I could take it all back, all of it, I would.”

For the first time, she wondered if she would want him to. At first, the pain of losing him made her wish, in that desperate, futile way anyone did when confronted with fierce heartache, that it had never happened and she was still back in California, frustrated in her ambitions, yes, but cozy and content as his mistress. With the balm of time, however, she could see what had been restored to her, her nieces and nephew, her friendship with Ruthie, and her love for the theater.

“It’s too little too late,” he said. “I know all that. That’s why I wish you’d just let me go. Forget you saw me.” He coughed and coughed.

She gave a disbelieving shake of her head. As if forgetting a second time could be so easy.

“I know you’re sore with me,” he said, when the coughing had abated. “You got every right to be.”

She sneaked a glance at him. He’d produced a hotel ashtray she hadn’t seen him take and was tapping his cigarette into it. If he weren’t deaf, she would have told him not to smoke when he had a cough. She would have told him that she wasn’t angry until he had reappeared. At least, she thought she hadn’t been. She wasn’t sure of that now. She settled for a shrug.

“Coming out here, I thought you might be pregnant. I know I just let you skip town and you could have been …”

He looked away and coughed and it struck her then just how much discomfort he was in, far more than she was, although she was scarcely comfortable. She knew how much he detested conflict and couldn’t begin to guess how much it was costing him to sit here and explain himself. Had he really believed that it would be as simple as handing over a bouquet of flowers? Misunderstandings in Shakespeare’s comedies could be resolved with as much, but she and Buster weren’t in a play.

A knock on the door, which he couldn’t hear of course, saved her from having to answer him. She stood and took two quarters from her purse for a tip before answering it. A concierge was standing in the hall with a tea cart. She tipped him, wheeled it inside, and parked it near the bedside table and filled two mugs with steaming tea from the white ceramic teapot. She handed Buster his and he took it wordlessly, his cigarette now stubbed in the ashtray that he’d set at the foot of the bed. Her stomach churned. She’d begun to feel hungry as she’d stepped out into the night with Harry and the gang, but she couldn’t stand the thought of food now. She sipped her tea and Buster sipped his. He coughed and the tea sloshed onto his pants, and she stood and refilled his cup without saying anything. When they were finished, she handed him the small paper bag of lozenges. He fished one out, unwrapped it, popped it in his mouth, and set the bag on the floor. The smell of licorice filled the room.

She took up the pad again, but nothing came to mind. It had always been so easy with him before: easy to chat with him, to hold him in her arms, to laugh at him, to love him.

Busted rolled the lozenge around in his mouth and it clinked against his teeth. She realized she would probably catch his cold in a couple days, and she still had a whole week left of performances not counting the matinee. After a couple minutes of uneasy silence, he rose to his feet and went to his suitcases. She watched him bend down and heard him rummaging in one. When he came back, he handed her a section of the Tribune that had been folded to a particular page. Her eyes immediately tracked to a headline that read BUSTER KEATON SKIPS TOWN AMID DIVORCE AND NEW PICTURE.

Reports coming out of Hollywood assert that frozen-faced comedian Buster Keaton has mysteriously left the city of Los Angeles one week before filming was to wrap on his new picture for M-G-M. His departure coincides with a divorce suit brought two weeks ago by Mrs. Natalie Talmadge Keaton. Mrs. Keaton has alleged adultery against her deadpanned husband, with rumors swirling about town that he was discovered in her bed with another woman the night before the divorce was filed. His unhappy wife also cites mental cruelty, stating that her spouse would disappear for days on end, refusing to tell her where he was going or what he was doing, and humiliate her in front of their family and friends.

Correspondents in the movie capital say that Keaton failed to show up for filming last Monday and M-G-M was unable to reach him at his Italian Villa home. Witnesses describe seeing him board a train headed East shortly after. It is not known where the comedian was heading or when he planned to be back. Some suspect a publicity stunt to win back Mrs. Keaton.

In a statement today, the studio said, “We are not worried about Buster taking a little time off. He has had a busy year and, needless to say, recent upheavals in his personal life have caused him strain. Although our desire was to finish the new picture by Christmas, we have been ahead of schedule and do not in any way feel that the film’s release will be delayed. We respect Buster’s decision and expect him back any day now …”

The article went on for another two paragraphs, but Nelly set it next to her on the bed. Again, she felt sick. She knew when she left California, though she tried not to think of it at the time, that Buster would inevitably move onto other women, but reading about it made her ache with jealousy and anger. She felt ashamed for him, ashamed of him, and bitter all over again.

“Oh Buster,” she said, looking up at him where he silently stood.

“Oh Buster is right,” he said, reading her lips. He paused to cough before saying, “That ain’t even the half of it. I went kinda crazy after you left. Didn’t even try hiding the girls from Nate no more. Even before the big scene with the cops and the detectives, I couldn’t hardly get her to say a word to me. I’ve been catching it left and right from everybody. Constance is apoplectic. Eddie Mannix’s been cooking up stories to cover my hide. Hell, I don’t know if I’ll have a contract when I get back to California. We still got a week to go on shooting and every day I’m gone is costing ‘em thousands. Folks still get their salaries whether I’m there or not.”

As he spoke, he had taken out a cigarette from the packet in his trousers pocket and torn the paper off absently, never lighting it. Now he went to the tea tray and picked up the Vick’s VapoRub, which he tossed casually onto the bed. He started unbuttoning his jacket, then his shirt.

Nelly looked away. It reminded her of the first time he’d undressed in front of her at the foot of the dock and she’d been too shy to look at him. In her peripheral vision, she saw him toss his shirt and jacket onto the bed. After a coughing spell, he sat next to her again and she could smell the mentholated ointment as he unscrewed the jar. She averted her eyes as he applied it, though she didn’t think he’d removed his undershirt. She found herself wishing that she was at the Green Door with the rest of the gang, enjoying a chicken dinner and anticipating a night of dancing and merriment at the Aragon. In her head, a band played “Sweet Georgia Brown.”

Buster stood up and set the jar of VapoRub on the bedside table, appearing briefly in her line of vision. He was wearing his undershirt and she caught a whiff of his familiar cigarettes-and-sweat smell mingled with the ointment. The bed sank as he sat back down.

“I don’t know what to tell you,” he said. He bent over as a cough wracked him. “It made sense when I got on the train. I should have thought more about how you’d feel seeing me again.”

Again, she couldn’t argue with him. She looked down at the pad and pen, which had found their way back into her hands. She couldn’t think of a thing to say.

“I know I said I’d write you. Talked myself into thinking you wouldn’t want to hear from me, I guess. I felt awful for leaving those pictures around and messing it all up for you.”

She looked at him. He was biting his thumbnail, looking fretful. She considered the pad of paper again.

What did you think of the play? she wrote.

Buster leaned over into her space to read the words and her skin prickled.

“What’d I think of the play?” he said, pulling back and looking surprised.

She nodded.

“Well it was alright I suppose, but I couldn’t hear a darn word of it. It was like watching a picture without title cards,” he said. “I did what you said though, I watched the action and tried to figure it out that way. You didn’t like Benedick, but your friends told you he was in love with you so you fell in love back. Don John tried ruining Hero’s reputation. And in the end it all worked out.”

For the first time, she couldn’t help smiling. He had gotten it right.

“I gotta be honest with you, I didn’t much care that I couldn’t hear,” he went on. “You’re great at acting. You did it all by yourself too, just like you wanted.”

Her heart felt like it skipped not one but two measures. She didn’t want to care for him, not when she’d come so far. She squeezed her eyelids together for a few seconds.

“Anyway …” He trailed off and pressed his fingers against a cheekbone and rubbed. His eyes looked shiny. “Anyway, that’s why I shouldn’t have showed up. Everything’s going so good for you. You didn’t need me to barge back in and—” He stopped and said, “Nate says she’s taking the house and the kids, too.”

To her shock, his voice cracked on the words.

“I ain’t going to fight it,” he said. “She can have everything. She can have my—my boys. I guess you think I’m here because I’ve got nowhere else to go, but you’re the reason I fell apart in the first place. I suppose I was thinking I could say sorry and everything’d be okay, but ...”

He turned away from her to hide his tears, but she could hear him begin to weep.

Her own eyes flooded and pen and pad dropped from her hands. “Oh Buster!” she said. She closed the space between them and wrapped her arms around him, unable to be cold-hearted one second longer. “I still love you.” She pressed her face into his neck, her tears wetting his skin. Even though he couldn’t hear her, he seemed to understand because he clutched her against him as he cried. She’d never seen a man cry before. That it was Buster made it ten times worse. “I’m here, darling, it’s okay,” she said, squeezing him back and crying with him. “I���m here.”

It was many minutes before the shuddering of his ribs stopped. She held him throughout, rubbing his back and stroking his hair. At last, he sat back and pulled a handkerchief out of his trousers pocket. She found hers in her handbag, which she’d laid on a pillow earlier without noticing. She didn’t mind that there was a damp spot on her shoulder from his running nose or that he had coughed on her several times. All she could think was that she still loved him and that they would figure things out, somehow, someway. They blew their noses and dried their eyes. Buster stood up and poured himself another cup of tea.

“Here I am with all my bridges burned,” he joked weakly, taking a sip.

She sat with her knee pressed against his as he drank his tea. She was no longer sure what time it was. In a way, she was grateful for his cold. She still didn’t know what she wanted to say to him. Just feeling seemed to be enough for the moment.

I’m going to run a bath for you, she wrote, after they had sat in silence for a few more minutes with only his cough to break it. Hot water will help your cough.

Buster nodded. “Alright.”

In the bathroom, she sat on the edge of the tub as the tap ran and tested the temperature every minute or so to make sure that the water was just short of scalding. Buster came and sat on the toilet seat. He was smoking again.

“You shouldn’t smoke when you have a cough,” she said, before remembering he couldn’t hear her.

“Huh?”

She mimed coughing, taking a drag from a cigarette, then pretended to grind a cigarette underfoot as she shook her head.

“Alright, alright.” He turned on one of the sink taps and extinguished the cigarette in the water. Without any self-consciousness, he started to unbutton his trousers.

She shook her head, but he’d already stepped out of one leg.

“What?” He stepped out of the other leg and coughed.

She shook her head again. She wasn’t quite ready to resume their previous level of intimacy. It seemed too precipitous with their reconciliation so delicate and new. She felt guilty about Harry too, she realized. He had been good to her even if she hadn’t returned the depth of his affection and she owed him a formal break-up before she embarked on any sins of the flesh with Buster. Of course, it was ridiculous to even let her thoughts roam in that direction. She didn’t think Buster meant anything by undressing in front of her, and even if he did he was hardly in a condition to make love given his fearsome cough. She had more to fear from her own desire than his. Though this was all too complicated to explain in writing (and she’d left pen and pad on the bed regardless), Buster appeared to understand and sat back down on the toilet lid, obedient if not quite chaste, clad as he was only in underwear.

When the tub was sufficiently full, she motioned him over. It’s very hot, she mouthed.

“Trying to boil me to death?” he said, tugging his undershirt over his head. Beneath it, he was still beautiful and she kept her eyes above his collarbones after a brief glimpse.

She motioned her head toward the bedroom before leaving the bathroom.

A few moments later, she heard him cry out. “Now I know you’re trying to kill me!” he said.

She laughed for the first time, then remembered Natalie and some of the pain trickled back in. No matter which way she turned after this, more pain was on the horizon and the thought made her feel sober. She dialed the front desk and ordered roast beef sandwiches and soup to be brought up, then sat on the edge of the bed waiting for Buster to be done. Only his coughing broke the silence.

When he came out, his skin was pink, a towel was wrapped around his waist, and the soup and sandwiches were waiting on the tea tray. She thought he was coughing less, but it was hard to say. “Where’d these come from?” he said, motioning at the tray as he walked around the bed. She shrugged modestly and kept her eyes directed away from him as he snapped open his suitcase for a change of clothes. He changed in the bathroom and came out in white pajamas with thin blue stripes, smelling like hotel soap, his feet bare.

“Thanks,” he said, nodding toward the food. In the time it took her to finish half a sandwich, he wolfed down a whole one as well as a bowl of soup. “Something the matter with your appetite?” he said, finally looking up from his plate.

She tore at the corner of the second half of her sandwich and shrugged. The trepidation had crept back on her and she wasn’t feeling hungry anymore.

“Thought it looked like you’d dropped some weight,” he continued, glancing her up and down.

She gave up and set her plate on the tray. Just working on those twenty pounds I need to get into pictures, she wrote on the pad, but the joke fell flat.

“You really going back into pictures?” said Buster. He looked surprised and she could tell he believed her.

“No,” she said, shaking her head.

“Didn’t think so,” he said, sounding a little deflated. He coughed into his elbow, plopped another sandwich onto his plate, and sat back down on the edge of the bed. He took a bite and swallowed before saying, “I know you haven't made your mind up about me. It’s okay.”

She smiled in spite of herself at how well he still understood her and reached out to stroke his damp hair away from his temple.

It’s very sudden, she scribbled. I never thought I’d see you again.

He read and took another bite of his sandwich. “I was talking to Louise—my sis Louise, I mean—when it all clicked.”

She didn’t understand, but nodded.

“I was only thinking about me, though. Wasn’t thinking that you might—” he paused. “Well, I wasn’t thinking.”

That I might have moved on? she wrote.

“No, no,” he said, his half-eaten sandwich abandoned. “Figured it was a possibility. Maybe you were pregnant and your family was taking care of you. Maybe you weren’t and you had a fiancé by now. Maybe you didn’t want to have anything to do with me, maybe you did.” He looked toward the curtained window, his focus distant. “Wasn’t thinking how it would be, you walking out that theater door with your fellow perfectly happy never seeing me again. That’s when I knew it was wrong to try and interfere. I wish I’d just let you be.” He didn’t sound self-pitying, just matter-of-fact.

She considered how to answer. There were mights, maybes, and shoulds aplenty, but for better or for worse they had ended up here.

Well we can’t change it, she wrote. All we can do is decide what to do now.

That decision had hovered over them since they’d stepped into the hotel room. Buster set his plate on the tray and knit his hands.

“I knew what I was gonna say, coming out here, but something tells me you won’t be on board.”

She looked at him, taken aback. Her body seemed to go both hot and cold simultaneously. Was she hearing a proposal?

Not on board with what? Her face was warm.

He shrugged. “Forget it.” They fell back into silence again with only his coughs and the tick-tick of the radiator to punctuate the stillness.

She bent over the pad again. We need to decide regardless.

He looked at the pad. “Well, what d’you want?”

The question gave her pause. I want to finish out the play, she answered, after thinking about it.

“And then?” He bit at his thumbnail again.

I don’t know, she said. She tried to peer into next week or next month, but even tomorrow was opaque.

“You engaged to him?” he said. His expression was blank.

Who? she wrote, though she guessed that he meant Harry.

“The fellow you walked out the back door with. The one who played Don John.”

No and I’m going to break it off with him. Even before you showed up he was dull as dishwater. She gave a wry smile as she passed him the pad.

“Well,” he said slowly, studying her after he’d read her reply, still grave-faced. “What is it? You afraid to go back to California ‘cause of the blackmail? I’ve done a lot of thinking about that, you know, and honest to God, I don’t think it matters none. In fact I’ve asked myself ever since that day why I ever thought it was a big deal. It isn’t. Louise Brooks sued a fellow who took some photos of her in her birthday suit and won. If the girls try anything against you, it’ll never stick.”

She shook her head. I need time to think. Let’s just sleep on it.

“Sleep here?”

She nodded. She could go back to the Blackstone, but nothing said Harry wasn’t waiting there. She could also take a room at the Allerton, but selfishly, maybe foolishly, she wanted this night with Buster.

He rubbed the back of his neck. “Okay.” He nodded. “Not sure I’m in any condition to—well, you know.”

She had to laugh. Is that all you think I think about? When I say sleep I mean sleep. You look like you haven’t slept in days.

“Had a hard time with it on the train,” he acknowledged. “We got in real early this morning, too.”

I’m tired too. It’s been a long day.

He nodded. She reached out and touched his shoulder. “It’s okay,” she said, though he couldn’t hear her.

It wasn’t like the last time she’d stayed with him at the bungalow, when they’d stood in front of the mirror and brushed their teeth together, Buster trying his best to make her laugh so that she would spit toothpaste everywhere. He left her alone as she took her turn in the bathroom. She washed her face, brushed her teeth with a finger and some of his toothpaste, undressed down to her chemise, and splashed a little water and soap under her arms. Exhaustion had crept up on her. She considered her hair and decided just to sleep on it, bobby pins and all. When she walked back into the bedroom, Buster had gotten rid of the tea cart and was standing next to the window with the curtain open, smoking and looking off into the night. He turned around and ground out his cigarette when he saw her.

“Your turn,” she said.

“Huh?” he said, cupping his ear.

She shook her head with a small smile and cocked her head at the bathroom. He disappeared into it. She got rid of her purse, the newspaper, and the ashtray, and lifted the white coverlet and white sheets of the bed. Buster wasn’t long. She could smell toothpaste on his breath as he passed by on his way to close the curtain and turn off the floor lamp by the table. He cleared his throat as he held up the sheets and slid in next to her.

“Aren’t you gonna take your hair down?” he said, sitting propped against his pillow.

She shook her head and grasped for the pen and paper on the bedside table. Too tired and I only have a comb on me.

He looked at her for a few seconds. “I’ve got a brush. Want me to?”

She started to say tell him no, it wasn’t a big deal, but something in the way he was looking at her made her reconsider. She nodded.

He returned a minute later and she sat up straight as he crawled in next to her. He sat with one leg folded beneath him. “Just take out the pins?”

She nodded and bent her head. His fingers searched through her hair and began to pull out pins. They came out easily with no pinching. He stroked a section of hair hesitantly with the brush. She took it from his hand and demonstrated that he could use more pressure. He returned her nod. At any other time, the moment would have been utterly surreal and strange, but she was exhausted both bodily and emotionally. His touch felt good and that was all she cared about.

“Did I get ‘em all?” he asked after a few minutes.

She felt around in her hair and found that he’d only missed three. She showed them to him and he set them on his bedside table.

“Turn back around,” he said. He ran the brush through her hair with a firmer hand this time, but he was still gentler than she was. After every stroke, he caressed her head with his other hand. Her eyes closed. She had been a child the last time someone had combed her hair and had forgotten how soothing it was. She thought she could fall asleep right then and there. “There, how’s that?” he said finally.

“Mmm,” she sighed. She shifted around and met his eyes, and his expression was so honest and vulnerable that she didn’t hesitate to put her arms around him. “I love you with so much of my heart that none is left to protest,” she whispered in his ear.

It didn’t matter that he couldn’t hear her. He must have known, and that was the thought that carried her off as she fell fast asleep next to him.

Notes: Thank you to @savageandwise for being such a thorough beta. There’s no one else I’d trust to “preview the rushes.” This was such a delicate chapter that I took my time in revising it and substantially altered it from the original version around the same time I’d written Chapter 13, the chapter where Nelly first attends a party at the Villa.

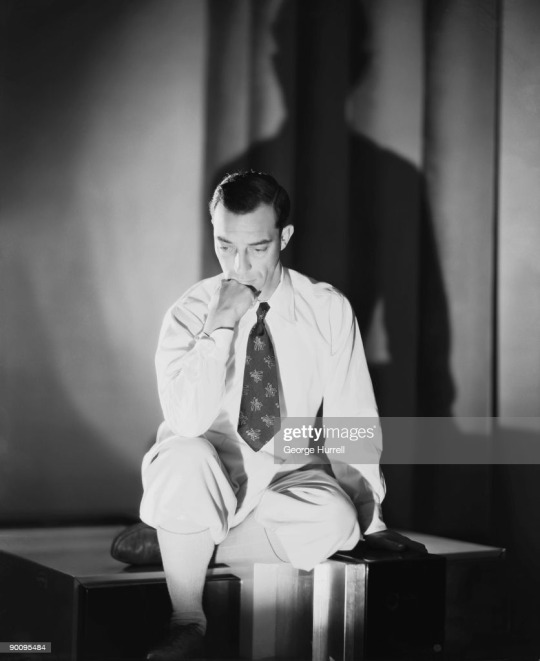

This will be the third-to-last chapter. Though this chapter takes place at the end of 1928 and the photo of Buster is from autumn 1933, I envision that Buster as being the one whom Nelly encountered. Drinking, disheveled, sad, lost.

The penultimate line is delivered by Beatrice to Benedick in Much Ado.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Chapter 41

Natalie’s wardrobe would have clothed a thousand empresses for a thousand years. Buster had never really appreciated before just how many outfits she owned. Every color in the rainbow was represented and every fabric too, silk, organdy, taffeta, chiffon, voile, law, and lace. For every dress, there was a pair of shoes: heels, slippers, Oxfords, boots, tennis shoes.

The blonde girl next to him was struck speechless. He’d found her outside of the casting office at the studio a few hours and several drinks earlier and had already forgotten her name.

“This one,” he said, going for the brightest red dress. He pulled it off its satin hanger and draped it over the girl’s arm. “Try it on.”

She looked momentarily uncertain, but obediently hooked her arms behind her back and began unbuttoning her dress. She slipped it from her shoulders and it pooled at her feet. Underneath, she was wearing a light turquoise girdle over a creamy slip. For a moment, he considered abandoning the fashion show and just taking her to bed, but this was important. He nodded at her to continue and she pulled the red dress over her head, tying it at the nape of her neck when she had straightened it over her hips.

“How’s it look?”

“Just swell,” he said. He reached into the row of dresses and grabbed something peach-colored with a transparent black overlay, trimmed with black ostrich feathers. “Now this one.”

She tried it on and posed for him, swishing this way and that. It was a beautiful dress. They were all beautiful. He made her try on a pink one made of Chinese silk, then one of gold lamé. Eventually she just stood there in the girdle with her hands knit in front of her as he made a pile of dresses at her feet.

He felt very good about the task as he went about pulling the nicest dresses from their hangers. It felt like doing laps in the pool or taking a brisk run in the summer air.

“Alright,” he said at last. The pile was as high as her knees now. “These all belong to you now. Let’s get ‘em into the other room.”

They stooped to gather the dresses up and he motioned her to follow him into Natalie’s bedroom. He dumped the dresses in the center of the bed and the girl followed his lead. The bottle of whiskey was where he had left it, on the side table where his wedding picture sat. He topped off both their glasses, knocked his back, then refilled it. He returned to the closet and grabbed two suitcases, which he slung onto the foot of the bed. This accomplished, he handed the girl her glass of whiskey and sat next to her on the edge of the bed. She took a tentative sip, looking at him for instruction.

It was evening now. The drunkenness rested on him like a heavy cloud. He struggled to think of what to do next. Then he remembered the girl. He finished his drink and set the empty glass on Nate’s bedside table, then bent over and fiddled at the girl’s hip with the buttons on the turquoise girdle. She lifted her hands to his belt. They peeled everything off, even their socks and stockings, but it wasn’t any use. He was too drunk. Whether the girl cared, he didn’t know. The cloud was so heavy now that he couldn’t keep his eyes open. He rolled off of her, pulled her into his arms and, half-lying on the dresses, passed out.

“Get up, Buster.”

He opened his eyes. They were filmy and he blinked rapidly, trying to clear them. He didn’t know how long he’d been asleep, but it was evening still; the room was still dark save for soft lamplight. His mouth was dry, he had to piss, and his thirst seemed unquenchable.

The voice was Natalie’s. He raised his head from the pillow and found that she wasn’t the only one in the bedroom. Dutch was standing next to her at the foot of the bed with her arm around Nate’s waist and three men he didn’t recognize lingered there too. Gradually it occurred to him that he was naked. Curled against him in an unconscious stupor, her skin sticky and sweaty where it met his, so was the girl. This couldn’t be right. Natalie and Norma were at Lake Tahoe.

“What gives?” he croaked. As he shifted himself to his elbow, he could feel that he was still blind drunk.

“This is it,” Natalie said.

He didn’t comprehend, but he knew that he’d stumbled into some deep and irreversible danger. Next to him, the girl was stirring. “What’s going on?” she said groggily.

“It ain’t what you’re thinking,” he said to his audience of five. “Nothing happened.” Realizing that the denial wasn’t convincing, he admitted, “I was too drunk.”

“Can you come here, ma’am?” one of the men said. He had produced a dressing gown of Natalie’s and was trying to avoid looking directly at the naked girl.

The girl slid off the bed and her modesty was duly robed.

“Get her a taxi,” another man said in an undertone, and the third man disappeared from the room with the girl.

Buster pulled himself to a sitting position and extracted a pink taffeta dress from beneath him, using it to cover himself. He tried to come to grips with what was happening, but just wanted to go back to sleep.

“What’s with the dresses and suitcases?” said the first man.

He shrugged. The importance was lost.

“He was trying to give them to that slut, I suspect,” Constance said.

He squinted at her. Nothing about the whole scene was making any sense. “Who are these guys?” he said, looking at Natalie.

“Detectives, sir,” said the second man, nodding to the third as he reentered the room. The girl was not with him.

“Mr. Giesler. Mrs. Keaton’s attorney,” the first man said.

Slow comprehension dawned on him. “You set me up,” he said to Natalie.

Constance looked exasperated. “No one set you up, you great buffoon. All we did was keep our distance and watched you hang yourself.”

“Mr. Harris has been following you,” said Natalie. She gestured to the second man.

No one wants to hear my side of the story,” he protested.

“You have no side of the story,” Constance said, snapping.

He opened his mouth, but quickly closed it. Even dead drunk, he could tell he was in serious hot water.

The first man cleared his throat. “Perhaps someone could get Mr. Keaton some clothes,” he said, addressing the second and third man.

Buster submitted. He couldn’t remember where his had gone. They brought him a dressing gown and change of clothing, and he stumbled into Nate’s pink bathroom robed in the dressing gown to relieve himself and get dressed. His head swam and he wished he could think clearly. When he exited the bathroom, Natalie said matter-of-factly, “I’m staying with Dutch tonight. Mr. Giesler will be in touch tomorrow morning.”

He reached for her arm but Constance pulled her out of his reach and glared daggers at him. “Who’s Mr. Giesler?” he said.

“Me, sir,” said the first man.

“Oh, oh. The attorney. Right.” The feeling of danger and doom settled in the pit of his stomach, but he was still having a hard time grasping what was going on.

In the morning, everything became disastrously clear. A knock on the bedroom door woke him. When he answered it, Caruthers was standing there with some papers in his hand. “These just came,” he said. He handed them over along with a cup of coffee and Buster struggled to wrap his head around the phrase he was looking at.

Petition for a Dissolution of Marriage.

I, Natalie Talmadge Keaton, do hereby … He skimmed the rest of the paper, then let it fall from his hands to the bed. He didn’t understand half the legal mumbo-jumbo, but the important parts were clear as day: adultery, sole custody, support in the amount of $300 a month.

He sipped the coffee and tried to calm his racing heart. Natalie had been angry and made rash proclamations before. He just needed to give her some time to cool off. Nevertheless, he called Constance’s apartment as soon as he was finished with his coffee. When there was no answer, he called her seaside house. He called Norma. He called Peg. Nothing. He even called his ma and sis, but neither had seen Natalie.

“Why?” Louise asked.

He swallowed hard. “No reason.”

He attempted to distract himself the rest of the day, a swim in the pool, golf with Tom Mix, a few solo games of billiards. He tried to stay away from the bottle, but his head was throbbing so badly by four p.m. he finally had a few glasses just to make it stop.

The next morning, he drove to the studio. They were filming interior scenes for the yacht sequence, having wrapped up onseas filming the prior week. He wasn’t sure, but the crew seemed to look at him in a funny way. There was definitely something stiff in the way that Sedgwick said hello. When Dorothy pulled him aside to say quietly, “I’m very sorry, darling. How are you doing?” his worst fears were realized and he knew that it was in the papers.

He laughed it off. “She gets like this. She’ll come around.”