Text

On The Economics of Higher Education

I would like to ask you a question I've been thinking of for a while, if you have the time. I have just started my PhD in Anthropology in University of Helsinki, and I have been involved in quite a few student campaigns against university reforms (of neoliberal kind). Yet still all our universities are public institutions, there are no tuition fees and all students receive student allowance, so our situation is quite different than in, say, UK and US. I've been able to study two majors without acquiring any debt, which is quite common here.

My question is: Do you think university system that is publicly funded and free for all students (and adjunct staff is payed comparatively well) still has some of the irredeemable qualities that you describe in your critique of US elite universities?

Best wishes,

Viljami Kankaanpää-Kukkonen

Hi, I appreciate the question, thanks for letting me respond publicly so I don’t have to answer it more than once.

Before I answer your question let me say what perspective I’m speaking from. I’ve been in the US for 10 years. My involvement in American academia was mostly at private institutions on the East Coast, though I took a few seminars and spent time at Rutgers and CUNY, as well. Before that, I did my undergraduate education in Berlin at the Free University. I was in the last generation of students at the FU who graduated with a traditional German Magister degree; even before I graduated, the FU began to implement the accords of the Bologna Process, which aimed to unify educational standards across the EU and which led to a splitting of the Magister degree into American-style BA and MA programs. I haven’t been involved in European academia in the past 10 years. My “data” consists in 10-year-old experience with the German system; extensive 10-year-old familiarity with the British and French systems; and passing 10-year-old acquaintance with the Italian and Dutch systems. I’m sure that higher education in Europe has changed a great deal in the past 10 years in response to the pressures and forces you describe as “neoliberal,” so take everything I say in light of these ongoing developments.

Very simply put: the more “Americanized” an educational system becomes, the more its structure and consequences will resemble the structure and consequences of the American education system. The most distinctive feature of the American university system is its exorbitant cost, and its relation to debt and hence to the labor market. So the shortest answer I can give you is No, a free or cheap university system does not share all the dangerous implications of the American system. That said, the disciplinary and organizational nature of the European system is very similar to the American system and growing more so. I don’t think humans are “rational actors,” but I do think we constantly perform conscious or unconscious cost/benefit analysis, and I think it’s easy to see why the cost of an American higher education is much greater than the cost of a European higher education, not only in dollars but also in anxiety, in preparation, and in non-academic lifestyle commitments required to access and survive the university. The higher the cost of attending a European university becomes, the more that system will resemble the American one

That’s the short answer, and anyone who’s reading this can feel free to stop reading here; the rest of this post is just an elaboration.

Your e-mail mentions “other countries” generally, but I’m not comfortable speaking about countries I don’t know enough about. I’ve met and studied with and read papers by academics from all over the world, and I know some vague stories, but that’s not the same thing as having concrete knowledge of economic relations, so I’m going to localize the rest of my response and frame it as a comparison between the American and the European systems with which I’m familiar.

*

A free university system cannot engage the same socio-economic relation to the labor market and to personal debt that the American university system currently engages. The difference has to do with a different relation of the institution to the state and to private capital, as well as to the job market and to relations of labor and production more generally. For these reasons, I consider the European university less irredeemable and pernicious than the American one.

It shares many of the same features and problems, especially on the inside of the institution and in the production of knowledge, but I think the social role of the university is less compromised and dangerous and I think European universities could be improved more easily than American ones – for now. As we’ve already noted, the twin ideologies of privatization and austerity are pushing hard to “Americanize” higher education in Europe and elsewhere. The more successful these efforts are, the more irredeemable the university becomes.

Before I continue, please note that while I’m less critical of the European university system, I’m not holding it up as an ideal or a model or ignoring its very real problems. For example, I discuss the non-academic (vocational/professional) higher education system in many European countries as opening up more paths to financial stability than are available in the US. I stand behind that claim, but I’m also very aware that the parallel higher education systems in Europe have a classist function and a classist history, serving mostly to route upper and upper-middle class students to universities and poorer students to vocational schools. I’m also keenly aware that I went to university in a city (Berlin) that has more Turkish residents than Ankara, but I can count on one hand the number of Turkish students that sat in seminar rooms with me at that university. Etc., etc. This is not an encomium to the European higher ed system, it’s just a description of some crucial differences.

There are at least three major differences between the American and the European higher education systems:

· Debt

· Non-academic higher education

· Public system only vs. public/private dual system

I’ll expand on all these, but first we can observe that despite a profound difference in the economic relations in which the university is embedded, a fascinating aspect of the question is that there is fairly little difference between higher education systems in terms of content and style. You find the same plodding, obfuscatory writing; the same laborious processes of peer review; the same behind-the-scenes politicking and reputation-based privilege; the same interests and questions, though often with different approaches or angles; and most importantly, the same canon of concepts and thinkers and disciplines. This fact reinforces my belief that the discourse of the university performs a similar organizing social function (what Gramsci describes as “traditional” intellectual activity) everywhere, regardless of the specific hegemonic structure it’s serving or upholding. In this context, it’s worth distinguishing a critique of the university as an institution embedded in a specific economy from a critique of the discourses produced in the institution. These aren’t separate questions: there’s only one economy. But these questions operate in different registers, because the critique of the production of knowledge goes all the way back to Plato and beyond while the critique of the university’s current economic entanglements can’t go beyond the material history of those entanglements while remaining in any way immanent.

Back to the three big differences I listed.

Debt is the biggest one, by far.

I graduated from a European university debt-free. I paid registration fees every semester and I had to house and feed myself, but I didn’t have to pay exorbitant tuition fees. I certainly didn’t have to take out a loan at the age of 18 that would follow me the rest of my life. This difference is the single most important difference, because it doesn’t just change other relations, it changes the weight of other relations. A damaging situation is bad; a damaging situation is 100 times worse if you have no way of getting out of it or putting it behind you.

If you’re German and you get into a university and you find it utterly unbearable and traumatizing, you can just leave. You’ve spent some time, you might disappoint yourself or other people, but you’re not in debt, your parents didn’t spend $80,000. If you’re 20 years old and you’ve already signed the loan papers and you’re $80,000 in debt already after just 4 semesters, you’re going to think really fucking hard about starting over in a different program, or leaving school to do something non-academic. You’re much more likely to stay on a path you’re not happy with. And even if you do make the choice to leave, that debt can still follow you around the rest of your life unless you manage to adjust very effectively to a highly profitable new career path. If you spent $160,000 on a law degree from Yale then start practicing law and discover you absolutely hate it, you’re probably going to practice law for a few years anyway because otherwise you’re changing careers $160,000 in debt (that’s one hundred and sixty THOUSAND dollars). Minimum wage in Connecticut is currently $10.10 dollars an hour

Maybe this isn’t the case any more, but 15 years ago in much of Europe, you could decide academia wasn’t for you, leave the university, and get a job in a restaurant that would pay all your bills. In other words, you could shift gears to a much lower-pressure lifestyle without serious consequences. But imagine if you have serious student debt and you have $500 deducted from your salary each month? Suddenly you have earn more, even if you want a low-key lifestyle; you take on another job, or you find a job that’s higher-pressure even though you want to shift gears or whatever.

The costs of debt – in labor, in health, in anxiety – are enormous. In this way, there is a much tighter and more vicious link between higher education and the labor market in American than in Europe. There’s no other way to put it – the structure and pressures of the American system mean that Americans have to work, constantly, grindingly, in a way that many (not all) Europeans just don’t have to and honestly can’t understand. The American system presents a double bind: either you are bound to the labor market by debt because you did go to school, or you’re bound to the labor market by necessity because you didn’t go to school and are locked out of higher-paying jobs. The American university system is locked into the economy in a way that presents three options only: serve the system at the top; serve the system at the bottom; or succeed against all odds by being truly exceptional and carving out a space for yourself alongside the system or breaking into it in an unexpected way. There are very few paths to genuine economic prosperity that don’t run through the university system somehow.

The situation in the US hasn’t always been so dire; it got bad under Reagan and has been getting worse ever since. For a couple of decades after World War II, the G.I. Bill and a flood of money to universities made public higher education really affordable in the U.S. for many people. In the ‘60s or ‘70s in the U.S. (so I’m told, I wasn’t here), you could flip burgers for three months during the summer and save up enough money for a year’s tuition at a good state school if you were an in-state student; I doubt that’s still the case anywhere in the U.S., and certainly not at the more prestigious state schools.

Now that the American “middle class” has effectively vanished, we can see what role the university had in making that class disappear. An absolutely crucial element in that process was the defunding of public universities at the state and federal level, which led to massive tuition hikes that have made tuition at the most prestigious public universities almost as high as those at prestigious private ones. Capitalism played a major role in that process, because university pass their costs on to students by framing the rising costs as the availability of additional features, from trendy new disciplines to massive, ridiculous sports facilities. This is a “client-centered” approach to education that directly prioritizes students who can afford to pay. Basically, America no longer has a state-sponsored, debt-free path to prosperity, which Europe still does…for now. Defunding of universities and tuition hikes are the changes that will most quickly introduce debt as a decisive factor and bring the European system in line with the American one, with massive implications for the entire economy, not just for academia in some isolated, abstract way. Keeping the European university system free or at least cheap is unspeakably important and probably impossible at this point.

The relation between the education system and the labor market is also different in that many European countries have vocational or professional higher education that isn’t academic. That’s the second big difference. Craft and trade apprenticeships represent an important bloc that has no equivalent in the US, where most internships are professional position you get after you do a BA, and not instead of doing a BA (not always, but often). There are often but not always alternatives to university-style education in Europe. German interns (Auszubildende, or Azubis) are usually paid and can access no-interest government loans to support themselves when they aren’t. Many people I knew in Germany in the 2000s finished an academic Magister degree and then went on to do an Ausbildung in a completely different area (sound design, lighting tech, theater management) which then became their actual career. Here again the major difference is debt – you don’t need to take on massive debt to study nursing or hotel management in much of Europe – but there is also a difference in the need for critique of the institution. Simply put, if there are effective non-academic paths to prosperity, academics have less of an ethical obligation to critique and correct their institutions, and the institution has less of an exclusive onus to fight against inequality. If we consider “university students” as a socio-political bloc, that bloc is much more massive, diverse, and complex in the United States than it would be in much of Europe.

Third – and this too is linked closely to the question of debt rather than separate from it – a major difference between the US and Europe is the long-standing existence in America of extremely wealthy private universities. In Europe until recently there weren’t many private institutions of higher education. This was changing rapidly even while I was still there, and I’m sure it’s gotten worse. However, it will take a long time before new institutions acquire the prestige and surplus capital which American private universities already have.

The brilliant scheme of the American private university is that it took up the model and the rhetoric of the European, post-Enlightenment liberal university, but without sharing or adopting its economic model, which is that of a state-operated and –funded institution. The American private university is a European liberal shell over a fundamentally different economic motor, which is basically a massive private endowment of religious origin. The biggest American universities weren’t started to train scholars, they were started to train preachers; in this, they had more to do with the medieval canon school than with the post-Enlightenment liberal university. These universities acquired private wealth and land in the manner of traditional Catholic institutions, not in the manner of liberal European universities; now, centuries later, these institutions are basically giant pools of privately-held capital which have an enormous impact on the education, labor, leadership, scholarship, and values of the United States and, indeed, the world, but without any of the regulations that state-funded and –controlled institutions have to endure. These institutions are first and foremost corporate brands and wealth managers; they only teach students incidentally, as a kind of favor to the rich whose money they manage, but despite this they exert an enormous and unhealthy influence on higher education all over the world. For decades, the public university system in the US has worked extremely vigorously to imitate the private model, where instead the American public should have demanded the divestment of property from private universities, or at least an end to their tax-exempt status.

The impact of these institutions can scarcely be overestimated, but they are only the keystone of a vast system that all works together to produce and enforce inequality in the United States. Because the university is an instrument of hegemony and because capitalist hegemony always depends on inequality, the university under capitalism will always be in some ways an instrument and an enforcer of inequality. This statement is always true, but for that reason also fairly banal, because it doesn’t engage with any actual, specific material relations. The difference – as of now – is in the degree to which the entire system interlocks to trap and control the individual. Simply put, because in Europe there is less systemic inequality, less poverty, and more options for non-academic upward mobility (not many, but more than in the U.S.), the effect of the European university can’t be considered as pernicious and total as the effect of the American university. That doesn’t mean there isn’t much to correct and improve, it just means that capitalism has long tended to workshop its oppressions in the Americas first and then exported them elsewhere.

European systems, which have traditionally been national or nationalized, tended to have a single centralized application system and held rigidly to unitary standards of admission and education across the national system, even if certain schools had a better “name” or were more popular. But even before I left Germany, there were already efforts to declare certain universities in the national system “centers of excellence” and to pump money into those places. A major symptom of Americanization is the establishment of a corporate institutional hierarchy, often based equally on actual funding and on institutional PR, between universities in the public system. This idealistic appeal to merit and excellence justifies budgetary inequalities which in turn serve both to defund “less excellent” disciplines and to center education on the interests of funders and not students. Here too a “client-centered” corporate approach claims to serve students but is actually a pretense for increasing inequalities between them, and here too the same conclusion follows as above: the more tiered and hierarchical the national European systems become, the more inequalities will emerge that resemble those of the American system.

Another big difference between the US and Europe traditionally has been a much higher European emphasis on the humanities and “human sciences.” Scientists have always looked down on poets, but until fairly recently in Europe, it was equally the case the poets had the opportunity to publicly and emphatically look down on scientists. When I first lived in Germany as a teenager, I remember regularly seeing literary critics, poets, screenwriters, and other kinds of art and humanities people on TV, in panel discussions (broadcast on daytime network television!) and in newspapers. This too had begun to change by the time I left Germany, and I’m sure it has gotten worse. There’s a reciprocal pressure between intellectuals and institutions devaluing the humanities and the general public devaluing the humanities; as humanities programs disappear from the university humanities programming disappears from mass media. A primary ideological function of the university in modern society is to tell people what’s important and what counts as real knowledge. There are direct and significant consequences to the logic of quantification and its Four Horsemen, S, T, E, and M. Global warming would be easier to fight if so many people weren’t convinced life is impossible without tech, for example. These societal ideological formations don’t begin or end with the university, but they are upheld by it, promoted by it, and routed through it. Consider for example the ways in which STEM professions are dependent on corporations in a way that many humanities jobs aren’t. You can be a high school teacher pretty much anywhere if you speak the language; good luck being a freelance molecular biologist and crowdsourcing a lab. There are material and economic and personal consequences to ideological formations, that’s the whole point of enforcing an ideology, whether consciously or not. Here too it’s a question of degree; we already see the process happening. How far will you let it go? You often hear administrators tell you that the emphasis on STEM comes from students, who just don’t care about literature the way they used to. In my experience, this is nonsense. The proportion of humanities-oriented students and science-oriented students in the average classroom doesn’t change; what changes is the number of students who feel pressured or obligated to try and be science people when they’d rather be studying literature. That is my experience only, I haven’t done any studies.

The importance of fighting to keep European higher education free and accessible doesn’t rest on some liberal ideals of education and equality, but on the very real functions that higher education plays in the general economy, and in the relations of labor and production that express that economy. The European university often serves the interests of industry and private capital, but it is an arm of the state and transmits the values of the state and is susceptible to the pressures of private capital roughly to the same degree that the state itself is. But in America, the leading universities are expressions and instruments of private capital. They are inseparable from it, and they serve as instruments with which private capital applies pressure to the state, rather than as an apparatus of the state on which private capital applies pressure.

At the moment, the differing economic and social relations within which it is embedded make the European university less broken and less harmful than the American university, and with more potential for reparative change. But even as American global hegemony collapses, economic “Americanization” is on the rise everywhere. How far it will go, and what traditional institutions are destroyed or altered in the process, remains to be seen.

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

As a person well outside access to high academia, but with an interest in understanding the variations in current modern thought and my individual modern thought, and at least a workable familiarity with the historical influences that have led to each, I appreciate your accessible, generally open-source/non-profit didactic practice, I think it's a crucial way to share concepts and promote discourse. If you have any other recommendations for similar sources, please share. (ed. for char limit)

First of all, thank you for reading my work and for taking the time to send this message (twice!).

This might be a longish answer, but I think a big part of making philosophy accessible or useful is breaking down preconceptions people have about higher education/academia and about philosophy in general.

So let me start by saying that academia is not really a “higher” practice of education or knowledge, it is a more specialized and professionalized practice of education.

Universities don’t charge you for learning; they charge you for a piece of paper that says you’re an expert, and which says level of expertise you have, and then they tack on a surcharge for room and board. But universities don’t want you to think of it that way - they want you to think they are “bettering” you, because social value is crucial to their ideological position as “not-for-profit” institutions. They have to pretend do be doing something other than just collecting money. One way they do that is by hoarding intellectual and cultural resources, and making access to those resources contingent on your payment. In this way, they pretend they are giving you deeper or higher “content,” where in fact this content is just icing on the cake - what matters is the certification.

Unfortunately, this means that people less familiar with academia conflate the expertise that one is taught with the content that these universities hoard. I’m struggling to think of an analogy that isn’t stupid, but imagine that you’re a chef and a restaurant will only hire you if you can cook a specific food item. Now imagine that the recipe for this food item is hidden in a book kept under lock and key by a guild of chefs. The guild will only teach you how to make that one food item if you read the entire book and memorize all the recipes, but they’ll only let you do that if you pay them $50,000 first. If you have tens of thousands of dollars to spend and years to waste, maybe that sounds like an awesome deal to you. You wanted one recipe - and suddenly you know 100! Maybe competing with other chefs to see who can memorize all 100 recipes the fastest sounds like a really fun thing to you. But what if you really urgently need that job, and you just want to learn that one recipe? All you need is for someone to photocopy one page of the fucking book for you; you don’t need to read the whole thing, you just need to learn the one recipe to get to where you want to go.

This is more or less how knowledge and the university are related; they are a guild, not a free market. They have a lot of knowledge, and they try to keep it for themselves. If what you want is “content” in general, “learning” in general, then you’ll pay them for the privilege of swallowing whatever they feed you, hoping one day you’ll get to taste the food you want. But if you have specific dietary needs and concerns, or if you’re really hungry and you want to eat NOW, or you really and truly only care about that one recipe, then this whole scam seems exhausting, excessive, and inefficient.

So the first major distinction I want to make is a distinction between learning at a university and answering your own questions for yourself, which seems to be your goal. Are you asking me for intellectual resources with which to understand your world and your relation to it, or are you asking me for intellectual resources with which you can mimic and simulate the patina of higher education without paying that price tag? These are two different questions.

I would discourage you from the latter. If what you want is to convince a stranger or a friend or a potential employer that you have the equivalent of a fancy university education, you should mostly just listen to or read academic work that’s available freely on the ‘Net. A lot of academic discourse is about mimicry, not learning; you just have to learn which names to drop and how to pronounce key terms in French.

But if what you’re asking me is “Can I find resources online that will help me answer my questions and explore my relationship to the world as I might hope to do at a university?” then I’m happy to say there are plentiful resources available on-line at low or no cost that you can use to deepen your knowledge. “Low cost” is relative, of course, but relative to $60,000 a year at Duke or Yale pretty much every intellectual resource on the planet is dirt cheap. But if you have even $200-300 a year to spend on electronic resources and books, you can teach yourself pretty much anything you care to learn.

The first and most important resource available to any scholar on the planet is Wikipedia. I know it sounds obvious, but honestly Wikipedia is a fucking incredible way to delve into virtually any topic. It is, by and large, reliable, well-written, and in agreement with contemporary scholarly discourse (not always, but by and large).

Wikipedia may not go into as much depth as you want on some things, but it’s a great way to start figuring out what you’re interested in. As someone outside the fixed “coverage model” curriculum of the modern university, you have the big advantage of not wasting time on things that bore you. Don’t like medieval philosophy? Move on. Plenty of philosophical fish in the sea. Wikipedia will familiarize you with key name, periods, and terms; it will help you get a sense of what you do or don’t care about; and it will offer you footnotes. As you read, write down names of texts and collect links on the topics you find interesting. Just keep a Google doc or Word file or whatever open as you read, and copy book titles and essay links from Wikipedia as you go. You’ll find yourself with a pretty good initial bibliography, broken down by the areas you want to delve into.

I encourage you to make a financial contribution to Wikipedia if you use it often or rely on it. I give them $3 every couple of months and would give much more if I had more money.

Once you have that bibliography, you can start seeing which resources you can find on-line for cheap or free. Sometimes scholars put their old articles on their websites to download. Sometimes they’ll email it to you if you write politely and say “I’m a broke student without access to a library and I would really appreciate a copy of this article you wrote.” Many academics are assholes and won’t reply, but you’ve got nothing to lose. If you have even a little bit of a book budget, you might want to invest in a few key texts like the Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, which is deeply flawed but also really good as an introduction. If you don’t have even a little bit of a book budget, I trust your ingenuity to find a PDF of that Norton floating around the Internet.

Whether you are spending a few bucks or downloading shady PDFs, I can generally recommend the Cambridge Companion series. They aren’t all equally good; by and large the newer they are the better. These guides are intended as intro-level academese. That is to say, they aren’t written for a “general” or popular audience, but they are written for a highly-educated audience that knows nothing about the topic; they start from scratch and have wide coverage. These books are still strongly slanted towards academic concerns and will waste a lot of your time if you read them all the way through, but if you’re struggling with Spinoza or Deleuze you could do much worse than look at a Cambridge Companion to shed some light. The average chapter of a Cambridge Companion will teach you about as much as you would learn on the subject if you spent a semester in that academic’s seminar room.

The next widely available resource is audio and video. This includes recordings of lectures and classes; podcasts by and with academics and experts in various fields; and live-streams of conferences. Once you use Wikipedia to figure out what interests you, you can start using iTunes and YouTube and any other archival resource to look for free or cheap audio and video material on that subject.

You didn’t mention whether you’re near a decent public library. If you are, get a membership. Not only will you have access to their books, even a small public library will probably have access to all kinds of electronic resources, from Harvard’s Loeb Classics to JStor, Muse, and other platforms for contemporary scholarship and peer-reviewed articles.

One tip I can give you is that academics recycle the fuck out of every idea they have to keep pumping out publications. Sometimes a Wikipedia footnote points you to a big scholarly book by an academic, and you look it up and your library doesn’t have it and it costs $59 on Amazon or some shit. Never fear: that scholar has 100% published articles on that topic in several journals and you can probably at least get a sense of what they’re talking about from those essays, which are often available through a public library’s electronic access.

Many academics are now doing what I started doing years and years ago, which is taking their show on the road from the academia to social media. Everyone has a Patreon now. Most of these aren’t free, but just as $1 will buy access to hundreds of pages of text on my Patreon, $2-3 will often get you access to a lot of extra material from people who might actually know what they’re talking about. The good news about supporting a Patreon is that if the person turns out to be full of shit, you can unsubscribe a hell of a lot more easily than you can unsubscribe to being an undergraduate when you make that same discovery.

In general I encourage you to follow two things: individuals, and your gut. I say “individuals” as opposed to institutions, “fields,” or disciplines. One thing you see a LOT of academics do is follow everyone on Twitter who studies the same thing as them, whether or not they agree, disagree, or think the person is an utter fucking moron. I think that’s really dumb. I think it’s really dumb to compromise your ideas and your relationship with your readers and students for the sake of a veneer of “professional” cordiality that masks a seething dislike. Someone you like and trust in a different profession can teach you much more than someone in your profession who you can’t fucking stand. So follow people, not professions. Find scholars and academics you like and trust and listen to what they say, follow the links they point you to, engage if they are willing. Everyone is busy and oversubscribed but many people will still take the time to answer a quick question or offer a reference.

And by “gut” I mean just trust your instincts. If something is utterly fucking boring to you leave it and move on unless you have some serious reason for sticking it out. If one book by a writer leaves you tired, try a short essay by them, or their letters. Avoid scholars who sound like every other scholar around - they have nothing to teach you. Look for distinctive voices and exciting ideas; look for the people you trust, not the people with the most famous followers and longest publication lists. Getting published isn’t easy, per se, but it’s also not complicated, it’s just fucking exhausting and demeaning. I encourage you to follow people who spend most of their time discussing their own ideas rather than scandals and buzzwords in their field; follow people who are consistent both in quality and in their ethics; and follow people whose ideas and work don’t seem dependent on the institution and professional context they’re in. In other words, as someone outside the academy, you should care more about academics that give free lectures at museums and publish work in online magazines than you should about academics who mostly organize conferences and talk about their profession. For this reason I caution you that the person everyone in a certain field is buzzing around may not be the best scholar or the brightest thinker; they may just be someone who edits an important professional journal. That’s how academia works. Follow scholars who seem committed to their ideas, not to their jobs or universities.

This leads me to my final point, which is your reference to “modern” or “contemporary” scholarship in both your messages. I would caution you in two ways. First, a contemporary phenomenon does not inherently require new theoretical lenses to be understood. Listen - there are no new ideas. There just aren’t. History is fractal and so is human knowledge; things just cycle in and out at regular intervals but on a different scale. I categorically reject the fetish for novelty which is the hallmark of contemporary scholarship. We don’t need a new set of words that mean the exact same thing every 10 years. If one field already has a concept, you can just use that concept instead of inventing a really ridiculous new name for the same fucking idea. And so on. And so on. Don’t obsess over reading the latest theories and monographs. Contemporary discourse is free and widely available. To learn what ideas are occupying thinkers at the present time, to see what arguments people are making, you can read book reviews and magazine articles. Do I think the New York Times and the New Yorker are great and wonderful cultural beacons? I do not, I think they are often-disgusting publications that feature many great writers but also fundamentally serve the status quo and publish many despicable things. That said, a subscription to both of those publications along with the London Review of Books, the LA Review of Books, the New York Review of Books, and Bookforum will give you a pretty good sense of what the Zeitgeist is buzzing about at any given moment, whatever use that knowledge might be, and will cost much much less than actually going to Yale.

But again, knowing what the Zeitgeist is buzzing about isn’t the same as learning philosophy or understanding your own existence in relation to the world. Those things require slow, patient work. What matters is the work and your focus on it, not the names or books you read. I honestly and sincerely think that reading Spinoza or Hume is as useful and more pleasant than reading any contemporary scholarly text of the same length with “new” ideas. You are welcome to disagree, but you asked me for my opinion. I think reading great philosophy slowly and carefully will improve your understanding and your insight much more than reading new but mediocre or bad philosophy, regardless of what you then choose to devote that understanding and insight to. The key thing is how closely and carefully you read and think. To that end, many, many works older than the mid-20th century are freely available online, either entirely legally (Project Gutenberg; The Nietzsche Channel) or not-quite-legally (websites where you can download PDFs of new books both scholarly and not). Read Aristotle. Read Nietzsche. Read Marx. Read Rosa Luxemburg. Read Mary Wollstonecraft. Read W.E.B. Du Bois. All these thinkers are available for free. A free text is a free text, it doesn’t matter who’s hosting it. Check out Marxists.org and the Sacred Text Archive, for example; you might be surprised how many “philosophy” texts they hold.

I know I’ve given you much more general advice than I have specific references, but it’s hard to be more specific without knowing anything about your interests or focus. That’s why i encourage a little Wikipedia wormhole as a first step: find out and refine your interests. That’s a key step. After that, you can be much more systematic in tracking down the resources you need and start contacting people who might have access to more of them.

I think that with a little effort and a little chutzpah, anyone with an Internet connection can acquire a very advanced and sophisticated education. The quality of this education will depend on the time and effort you have available to devote to it, but that’s always the case. After all, what is an undergraduate degree but four free years of your life in which you aren’t obligated to earn money to support anyone? Many of us are crushed by debt and work and depression and anxiety and can’t dream of a vacation, much less 4 years of school. But if you have time, you can teach yourself anything without going to a university on the way.

35 notes

·

View notes

Note

As a person well outside access to high academia, but with an interest in understanding the variations in current modern thought and my individual modern thought, and at least a workable familiarity with the historical influences that have led to each, I appreciate your accessible, generally open-source/non-profit didactic practice, I think it's a crucial way to share concepts and promote discourse. If you have any other recommendations for similar sources, please share. (ed. for char limit)

First of all, thank you for reading my work and for taking the time to send this message (twice!).

This might be a longish answer, but I think a big part of making philosophy accessible or useful is breaking down preconceptions people have about higher education/academia and about philosophy in general.

So let me start by saying that academia is not really a “higher” practice of education or knowledge, it is a more specialized and professionalized practice of education.

Universities don’t charge you for learning; they charge you for a piece of paper that says you’re an expert, and which says level of expertise you have, and then they tack on a surcharge for room and board. But universities don’t want you to think of it that way - they want you to think they are “bettering” you, because social value is crucial to their ideological position as “not-for-profit” institutions. They have to pretend do be doing something other than just collecting money. One way they do that is by hoarding intellectual and cultural resources, and making access to those resources contingent on your payment. In this way, they pretend they are giving you deeper or higher “content,” where in fact this content is just icing on the cake - what matters is the certification.

Unfortunately, this means that people less familiar with academia conflate the expertise that one is taught with the content that these universities hoard. I’m struggling to think of an analogy that isn’t stupid, but imagine that you’re a chef and a restaurant will only hire you if you can cook a specific food item. Now imagine that the recipe for this food item is hidden in a book kept under lock and key by a guild of chefs. The guild will only teach you how to make that one food item if you read the entire book and memorize all the recipes, but they’ll only let you do that if you pay them $50,000 first. If you have tens of thousands of dollars to spend and years to waste, maybe that sounds like an awesome deal to you. You wanted one recipe - and suddenly you know 100! Maybe competing with other chefs to see who can memorize all 100 recipes the fastest sounds like a really fun thing to you. But what if you really urgently need that job, and you just want to learn that one recipe? All you need is for someone to photocopy one page of the fucking book for you; you don’t need to read the whole thing, you just need to learn the one recipe to get to where you want to go.

This is more or less how knowledge and the university are related; they are a guild, not a free market. They have a lot of knowledge, and they try to keep it for themselves. If what you want is “content” in general, “learning” in general, then you’ll pay them for the privilege of swallowing whatever they feed you, hoping one day you’ll get to taste the food you want. But if you have specific dietary needs and concerns, or if you’re really hungry and you want to eat NOW, or you really and truly only care about that one recipe, then this whole scam seems exhausting, excessive, and inefficient.

So the first major distinction I want to make is a distinction between learning at a university and answering your own questions for yourself, which seems to be your goal. Are you asking me for intellectual resources with which to understand your world and your relation to it, or are you asking me for intellectual resources with which you can mimic and simulate the patina of higher education without paying that price tag? These are two different questions.

I would discourage you from the latter. If what you want is to convince a stranger or a friend or a potential employer that you have the equivalent of a fancy university education, you should mostly just listen to or read academic work that’s available freely on the ‘Net. A lot of academic discourse is about mimicry, not learning; you just have to learn which names to drop and how to pronounce key terms in French.

But if what you’re asking me is “Can I find resources online that will help me answer my questions and explore my relationship to the world as I might hope to do at a university?” then I’m happy to say there are plentiful resources available on-line at low or no cost that you can use to deepen your knowledge. “Low cost” is relative, of course, but relative to $60,000 a year at Duke or Yale pretty much every intellectual resource on the planet is dirt cheap. But if you have even $200-300 a year to spend on electronic resources and books, you can teach yourself pretty much anything you care to learn.

The first and most important resource available to any scholar on the planet is Wikipedia. I know it sounds obvious, but honestly Wikipedia is a fucking incredible way to delve into virtually any topic. It is, by and large, reliable, well-written, and in agreement with contemporary scholarly discourse (not always, but by and large).

Wikipedia may not go into as much depth as you want on some things, but it’s a great way to start figuring out what you’re interested in. As someone outside the fixed “coverage model” curriculum of the modern university, you have the big advantage of not wasting time on things that bore you. Don’t like medieval philosophy? Move on. Plenty of philosophical fish in the sea. Wikipedia will familiarize you with key name, periods, and terms; it will help you get a sense of what you do or don’t care about; and it will offer you footnotes. As you read, write down names of texts and collect links on the topics you find interesting. Just keep a Google doc or Word file or whatever open as you read, and copy book titles and essay links from Wikipedia as you go. You’ll find yourself with a pretty good initial bibliography, broken down by the areas you want to delve into.

I encourage you to make a financial contribution to Wikipedia if you use it often or rely on it. I give them $3 every couple of months and would give much more if I had more money.

Once you have that bibliography, you can start seeing which resources you can find on-line for cheap or free. Sometimes scholars put their old articles on their websites to download. Sometimes they’ll email it to you if you write politely and say “I’m a broke student without access to a library and I would really appreciate a copy of this article you wrote.” Many academics are assholes and won’t reply, but you’ve got nothing to lose. If you have even a little bit of a book budget, you might want to invest in a few key texts like the Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, which is deeply flawed but also really good as an introduction. If you don’t have even a little bit of a book budget, I trust your ingenuity to find a PDF of that Norton floating around the Internet.

Whether you are spending a few bucks or downloading shady PDFs, I can generally recommend the Cambridge Companion series. They aren’t all equally good; by and large the newer they are the better. These guides are intended as intro-level academese. That is to say, they aren’t written for a “general” or popular audience, but they are written for a highly-educated audience that knows nothing about the topic; they start from scratch and have wide coverage. These books are still strongly slanted towards academic concerns and will waste a lot of your time if you read them all the way through, but if you’re struggling with Spinoza or Deleuze you could do much worse than look at a Cambridge Companion to shed some light. The average chapter of a Cambridge Companion will teach you about as much as you would learn on the subject if you spent a semester in that academic’s seminar room.

The next widely available resource is audio and video. This includes recordings of lectures and classes; podcasts by and with academics and experts in various fields; and live-streams of conferences. Once you use Wikipedia to figure out what interests you, you can start using iTunes and YouTube and any other archival resource to look for free or cheap audio and video material on that subject.

You didn’t mention whether you’re near a decent public library. If you are, get a membership. Not only will you have access to their books, even a small public library will probably have access to all kinds of electronic resources, from Harvard’s Loeb Classics to JStor, Muse, and other platforms for contemporary scholarship and peer-reviewed articles.

One tip I can give you is that academics recycle the fuck out of every idea they have to keep pumping out publications. Sometimes a Wikipedia footnote points you to a big scholarly book by an academic, and you look it up and your library doesn’t have it and it costs $59 on Amazon or some shit. Never fear: that scholar has 100% published articles on that topic in several journals and you can probably at least get a sense of what they’re talking about from those essays, which are often available through a public library’s electronic access.

Many academics are now doing what I started doing years and years ago, which is taking their show on the road from the academia to social media. Everyone has a Patreon now. Most of these aren’t free, but just as $1 will buy access to hundreds of pages of text on my Patreon, $2-3 will often get you access to a lot of extra material from people who might actually know what they’re talking about. The good news about supporting a Patreon is that if the person turns out to be full of shit, you can unsubscribe a hell of a lot more easily than you can unsubscribe to being an undergraduate when you make that same discovery.

In general I encourage you to follow two things: individuals, and your gut. I say “individuals” as opposed to institutions, “fields,” or disciplines. One thing you see a LOT of academics do is follow everyone on Twitter who studies the same thing as them, whether or not they agree, disagree, or think the person is an utter fucking moron. I think that’s really dumb. I think it’s really dumb to compromise your ideas and your relationship with your readers and students for the sake of a veneer of “professional” cordiality that masks a seething dislike. Someone you like and trust in a different profession can teach you much more than someone in your profession who you can’t fucking stand. So follow people, not professions. Find scholars and academics you like and trust and listen to what they say, follow the links they point you to, engage if they are willing. Everyone is busy and oversubscribed but many people will still take the time to answer a quick question or offer a reference.

And by “gut” I mean just trust your instincts. If something is utterly fucking boring to you leave it and move on unless you have some serious reason for sticking it out. If one book by a writer leaves you tired, try a short essay by them, or their letters. Avoid scholars who sound like every other scholar around - they have nothing to teach you. Look for distinctive voices and exciting ideas; look for the people you trust, not the people with the most famous followers and longest publication lists. Getting published isn’t easy, per se, but it’s also not complicated, it’s just fucking exhausting and demeaning. I encourage you to follow people who spend most of their time discussing their own ideas rather than scandals and buzzwords in their field; follow people who are consistent both in quality and in their ethics; and follow people whose ideas and work don’t seem dependent on the institution and professional context they’re in. In other words, as someone outside the academy, you should care more about academics that give free lectures at museums and publish work in online magazines than you should about academics who mostly organize conferences and talk about their profession. For this reason I caution you that the person everyone in a certain field is buzzing around may not be the best scholar or the brightest thinker; they may just be someone who edits an important professional journal. That’s how academia works. Follow scholars who seem committed to their ideas, not to their jobs or universities.

This leads me to my final point, which is your reference to “modern” or “contemporary” scholarship in both your messages. I would caution you in two ways. First, a contemporary phenomenon does not inherently require new theoretical lenses to be understood. Listen - there are no new ideas. There just aren’t. History is fractal and so is human knowledge; things just cycle in and out at regular intervals but on a different scale. I categorically reject the fetish for novelty which is the hallmark of contemporary scholarship. We don’t need a new set of words that mean the exact same thing every 10 years. If one field already has a concept, you can just use that concept instead of inventing a really ridiculous new name for the same fucking idea. And so on. And so on. Don’t obsess over reading the latest theories and monographs. Contemporary discourse is free and widely available. To learn what ideas are occupying thinkers at the present time, to see what arguments people are making, you can read book reviews and magazine articles. Do I think the New York Times and the New Yorker are great and wonderful cultural beacons? I do not, I think they are often-disgusting publications that feature many great writers but also fundamentally serve the status quo and publish many despicable things. That said, a subscription to both of those publications along with the London Review of Books, the LA Review of Books, the New York Review of Books, and Bookforum will give you a pretty good sense of what the Zeitgeist is buzzing about at any given moment, whatever use that knowledge might be, and will cost much much less than actually going to Yale.

But again, knowing what the Zeitgeist is buzzing about isn’t the same as learning philosophy or understanding your own existence in relation to the world. Those things require slow, patient work. What matters is the work and your focus on it, not the names or books you read. I honestly and sincerely think that reading Spinoza or Hume is as useful and more pleasant than reading any contemporary scholarly text of the same length with “new” ideas. You are welcome to disagree, but you asked me for my opinion. I think reading great philosophy slowly and carefully will improve your understanding and your insight much more than reading new but mediocre or bad philosophy, regardless of what you then choose to devote that understanding and insight to. The key thing is how closely and carefully you read and think. To that end, many, many works older than the mid-20th century are freely available online, either entirely legally (Project Gutenberg; The Nietzsche Channel) or not-quite-legally (websites where you can download PDFs of new books both scholarly and not). Read Aristotle. Read Nietzsche. Read Marx. Read Rosa Luxemburg. Read Mary Wollstonecraft. Read W.E.B. Du Bois. All these thinkers are available for free. A free text is a free text, it doesn’t matter who’s hosting it. Check out Marxists.org and the Sacred Text Archive, for example; you might be surprised how many “philosophy” texts they hold.

I know I’ve given you much more general advice than I have specific references, but it’s hard to be more specific without knowing anything about your interests or focus. That’s why i encourage a little Wikipedia wormhole as a first step: find out and refine your interests. That’s a key step. After that, you can be much more systematic in tracking down the resources you need and start contacting people who might have access to more of them.

I think that with a little effort and a little chutzpah, anyone with an Internet connection can acquire a very advanced and sophisticated education. The quality of this education will depend on the time and effort you have available to devote to it, but that’s always the case. After all, what is an undergraduate degree but four free years of your life in which you aren't obligated to earn money to support anyone? Many of us are crushed by debt and work and depression and anxiety and can’t dream of a vacation, much less 4 years of school. But if you have time, you can teach yourself anything without going to a university on the way.

35 notes

·

View notes

Note

If someone were having trouble getting through Matter and Memory (having already read Time and Free Will), would any other work by Bergson help in any manner? Or is there a secondary work you would recommend? I apologize if this question is too much of a basic request kind of thing. I'm just particularly interested in a line you would go to/through for this.

The best secondary literature on Bergson is Deleuze’s book Bergsonism, which I highly recommend whether or not you are struggling with Matter and Memory.

My best advice for getting through M&M is to treat Bergson’s thought exercises as just that - exercises. Try to visualize all his examples and diagram, to imagine them in three dimensions. How do the moving parts actually relate?

Good luck.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

...And Here My Troubles Began

293 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, just a simple question I've been meaning to ask since your large twitter thread about Spinoza a while back: is there an edition you'd recommend for the layperson? Thanks in advance!

I recommend Samuel Shirley’s translations, always, published by Hackett either in The Complete Spinoza or in a stand-alone volume of the Ethics and the Treatise on the Correction of the Intellect.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

First off, thanks for the work you do. I was reading about the inaugural protests and it seems like they are following the Occupy Model of a leaderless movement. Do you think it's possible for political groups to be both leaderless and potent? Why do new social movements insist on being leaderless at all? Is that a mistake? If you believe that social justice needs leaders, how can philosophy help us determine who they should be and how their power should be regulated? Thanks again.

Thanks for your message and thank you for reading.

Unfortunately, this isn’t a question, it’s a stream of consciousness. You can tell by the pile-up of question marks, each of which sort of touches on an issue only to come back immediately and look at the same issue from a different angle. You don’t have a specific question you want answered; you want help figuring out what it is that you’re asking. I’m very sympathetic to that; I think that formulating a proper question is the single most important, difficult, and productive part of intellectual inquiry. But it’s also work that you have to do for yourself. I’m not faulting you for being at this diffuse stage of thinking; it’s a crucial and inevitable first step of approaching any problem, and often the most exciting step. But I’m also not here to parse for you which of these questions you want addressed, especially when answers to many of them are in my archive already.

I think you’re asking vital and useful questions. I also think that answering all these questions would require a very lengthy piece of writing from me. More importantly, because I don’t have a clear conceptual question to address, the lengthy piece of writing you’re asking for would largely consist of opinions. Any question with the word “should” in it that applies to universal ideas and not to a specific context or example is a matter of speculative opinion, and these questions are too important to be answered in general or as a matter opinion.

For these reasons I’m going to pass on exploring these questions at any greater length at this moment, but I encourage you to continue thinking about them, to seek out other people who are investigating these questions, and to figure out with those people what the politics and movement-building appropriate to your specific interests, needs, and abilities might look like.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

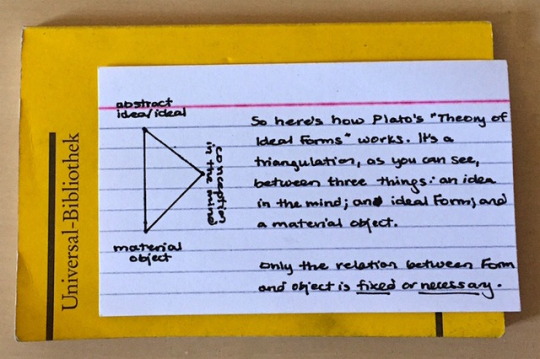

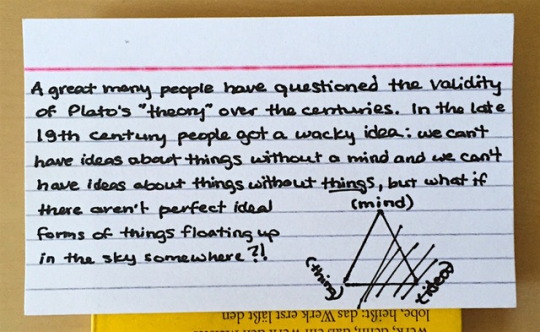

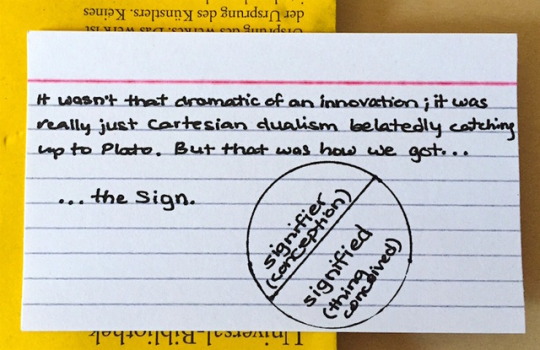

Is there a substantive difference between the terms "always already" and "necessarily?" If so, can you help me understand the distinction? Sorry for the really basic question, but neither context nor Google are helping me with the former term.

As with most metaphysical distinctions, how “substantive” you think the difference is will largely depend on how much the concepts in question matter to you. If you’re someone seriously invested in Derrida’s philosophy, you probably argue there is a profound difference. If you’re not, well...not. Let’s ask rather whether are able to distinguish the concepts, and not whether there “is” a difference between them. The answer to this revised question is “yes.”

The easiest way to distinguish the concepts is this: something is necessary if we cannot conceive of it as not being the case; something is “always already the case” if we can conceive of it as not being the case, but we can’t meaningfully conceive of a time when it wasn’t already the case. A Derridean or Heideggerian would tell you otherwise, but honestly the distinction is a conceptual or largely abstract one.

The simplest example I can give you is sexual difference. Is sexual difference necessary? I would argue that it isn’t, because there are many organisms that reproduce without it and evolution could have conceivably chosen a different path. But having occurred, we can say - and I would agree - that we can no longer conceive of the world as anything except sexed. So sexual difference is conceivably not necessary, but it has always-already happened, in that we can’t really undo its effect or go back to a state before its existence.

Necessity, in other words, is a question of necessity, which is its own metaphysical principle, while “always-already” is a question of temporality, which is a difference metaphysical principle.

This is the most clear explanation I can give at the present time without going into a great deal of metaphysics.

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

How can I register for your lecture!? Am I not seeing how and where to do that despite it being right in front of my damn face? Help? Thanks.

There’s nothing to “register” for. The lectures are held in Manhattan and free for anyone who wants to attend.

0 notes

Note

Is there a way to make the lecture series accessible for people who can't readily get to New York?

At the moment the short answer is, “Unfortunately not.”

The full text of the first lecture is available on my Patreon page for all supporters. Beyond that, there are plans to make the full series available once it’s over and I know how much material I have to work with. But in between I will mostly be posting snippets and teasers.

The “content” of the lectures isn’t radically different or new if you follow my work on-line. The lectures largely consist of new formulations of arguments I’ve been making for years across various platforms including this Q&A blog, so I don’t feel I’m denying you any urgent insights. Part of the concept of this lecture series is not just putting words together but creating a space, a place where people can come regularly to find a certain kind of atmosphere that’s conducive of a certain kind of thinking. An explicit aim of the lecture series is to think against anxiety, to think in a way that reduces anxiety. I think the Internet is a fraught place at the moment. I think livestreaming the lectures would open them up to an additional layer of anxiety that is counter to the stated aim. I don’t want anyone in the room to wonder if they’re accidentally on camera. I don’t want the speaker to feel like they’re reading in front of an unknown void rather than in front of 40 people in a room.

I am sensitive to the New York-centrism of the lectures. I know that a disgusting proportion of the resources, people, and institutions in the arts and humanities are already here. New York doesn’t need another lecture series the way some other places do. Unfortunately, this is where I am right now, and both my financial resources and my ability to travel are pretty constrained. I’m doing the lectures here because I believe in local, site-specific work, which is why I’m not livestreaming them, and I believe in community, and this is where I have a community of friends who are willing to serve as stand-ins for me while I’m still reluctant to be public. I recognize that you’re being deprived of a particular experience, and I’m sorry I can’t be in more than one city at once. But I think that if you can’t make it to the on-site lectures, having the entire series in your hand to read at your leisure, as a whole, will be a better substitute experience than reading them one by one or watching remotely. I hope you’ll agree once you have the finished product in your hand.

0 notes

Note

When you say the phrase there is only one economy can be understood as a reminder that all these discrete systems of representational value which we construct for ourselves are actually describing a single unitary relation of infinite parts" - is it possible that what Deleuze, in his reading of Spinoza, calls "extensive infinity" is in fact what bell hooks, in her reading of the interlocking systems of domination, calls "imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy"? Thnx 4 everything

In a word, no.

“Extensive infinity” is a very clearly defined metaphysical concept in Spinoza, as well as a very expansive one. The difference between Spinoza’s extensive infinity and the complex of issues hooks is talking about is easy to arrive at if you understand that “extension” basically means “material entities in three dimensions.” Since “imperialist white etc.” isn’t a concept that can meaningfully extend beyond the limits of the human sphere and since there are at least 2-3 other planets in the universe than Earth, there is no proper understanding of “extension” that allows for a correspondence between these two concepts, because it’s immediately inferable that “extension” (like “infinity”) is several orders of magnitude more abstract than any social relations of any kind.

If you have read Deleuze’s reading of Spinoza, you know that Deleuze describes Spinoza’s metaphysics are a kind of double helix, the order of essences moving in parallel with the order of actual existents. To put it more simply than I’m really comfortable doing, the phenomena hooks is talking about belong to the order of actual existents. Just as there are different kinds of “nothing” and negation is not privation, so too there are different kinds of “everything” and not every master category or general umbrella term is interchangeable for every other.

I would caution you strongly against the notion that any concept “is in fact” any other concept. Concepts are not trying to trick you. Concepts are not in disguise as other concepts. Every concept has a specific function, specific location, and specific parameters. Trying to decide if one concept is ‘actually just the same thing as’ another concept is a mode of paranoid thinking: it’s a way of reducing concepts to each other so that you end up having one less concept to worry about, instead of one more concept to use and think through. The productive question is, “In what ways do the two concepts resemble or differ from each other?” This question addresses the specificity of the two concepts as two distinct concepts instead of reducing one to a less-clear version of the other. What we have here are two distinct concepts.

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey, Have you read the paper 'sex in public' by Lauren Berlant? despite your distaste for dukepress, I think its somewhat in line with your thoughts on the social contract, and this paper seems to hinge on a lot of my problems lately. To make a long story short in this space, I fell in love with a boy two years ago, and started writing letters. the private letters i wrote, the direct and private address, seemed to be more terrifying, anxiety inducing, than public forum posts, indirect address.

I have not read this paper, sorry.

I do want to say that as a rule, theory should be framed in response to problems and not problems in response to theory.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

is there any reason you recommend wikipedia over SEP?

Yes, more people know about it.

1 note

·

View note

Note

In your recent discussion on truth and history you described philosophy as being about ideas. Following Deleuze and Guattari you also often describe philosophy as being about concepts. Do you see a difference between 'concepts' and 'ideas' or do you treat them as synonyms?

There is absolutely a difference between concepts and ideas. The two terms are like rectangles and squares. Every concept is an idea, but not every idea is a concept. By “idea” I mean simple an individual entity in the attribute of thought. Ideas are to thought as atoms are to extension: the closest we can currently come to describing the individual “units” of that attribute’s existing entities. Concepts are ideas that crystalize a particular problem and its attendant problematic. In this I follow, as you say, the claims laid out in Deleuze & Guattari’s What Is Philosophy?, which is where I would turn for a closer explication of the concept of “concepts.”

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

I've seen that you've been critical of some of the work that's come out of queer theory—I realize that's probably a generalization somewhat, but I was wondering if you could elaborate a little on what you find uninteresting or problematic with the writers you've addressed. Your critique of Butler makes sense to me, but there are a few writers in that field whose work I admire—specifically Monique Wittig, Jose Muñoz, and Eve Sedgwick. It's a broad question, but I'd be interested in your response.

I would recommend you do some digging in my archives since I’ve addressed this question at length on both Tumblr and Twitter.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

History and the History of Philosophy

Zak had a follow-up question to this question that I answered earlier this week.

We accept generally that philosophies’ characteristics are determined somewhat by the social/historical context they emerge during, but are there certain historical moments which demand a philosophy emerge. Like: did something about...WW2 (or the birth of TV or the founding of Athens) make philosophy more likely...Is it simply that disruptive ideas or events tend to produce post-Those Events philosophies in richer countries or is there a subtler force at work?

To answer this question we have to start with a distinction between two senses of “philosophy.” There is philosophy as an activity, and philosophy as an institutional-social form of collectively organized value. Just as there’s “I sucked another guy’s dick one time” on one side and “Being a lawyer for the HRC” on the other, so too there’s “Thinking [as activity] in response to an event” on the one hand and “Publishing a book about an event that other philosophers read.” Or maybe a better analogy is dancing. If you read a history of dance as a form, certain decades (the ‘10s, the ‘40s, the ‘70s) will be discussed as being particularly intense times of innovation and diversification. But what’s meant here is “dance as an institutionally and financially recognized art form”; that doesn’t mean that if you went to a wedding in the ‘50s fewer people would be shaking their butts than if you went to a wedding in the ‘40s.

The interesting thing about your question is that the answer to it is inverse in each case.

To the extent that “philosophy” is simply a conscious reflection about the world through the medium of concepts, I would be inclined to say that yes, dramatic events and socio-political upheaval increase wide-spread interest in philosophy, and more broadly in conceptual approaches to understand the world and reducing anxiety. If you think back to, say, the late ‘90s, most people would have described themselves as fairly moderate. Not a lot of people would have been comfortable declaring themselves fundamentalist Christians or libertarians, even if they had fundamentalist or libertarian tendencies, just as few people would have been comfortable announcing they were “radical queers,” even if their politics aligned somewhat with radical queer interests. I think socio-political upheaval, economic hardship, and other circumstantial historical difficulties send people running for fixes to their anxiety and along with religion, quack medicine, meditation, and militancy, interest in philosophy tends to soar during and after Hard Times as people struggle to come to terms with the world around them.

In the previous questions, I pointed out that because philosophy as a discipline is largely incarnated in the form of institutions, “great” or “successful” philosophies tend to be those which pass through the gatekeeping-filters of those same institutions. However, the socio-political conditions that spur “ordinary people” to grope after philosophical answers also tend to destabilize institutions, interrupt their chains of transmission, and make texts harder to find, publish, and preserve. So that the periods in which “grassroots philosophy” tends to peak are usually opposite to the eras in which the world’s best-known philosophers worked and wrote. I know that my on-line schtick is rapid-fire philosophy and I do think Thought can be an immediate, strategic response to the world, but the real truth is that good philosophy requires stability. Learning to think requires calm and patience and resources. I can do what I do because I had the massive privilege of having multiple years of fellowship to literally do nothing but sit at home and absorb the history of philosophy and train my mind. It’s a lot like building muscles: if you don’t have the time to spend 3-4 hours a day at the gym, only serious drugs will make you huge, and the muscles will shrink as soon as you stop taking those drugs. We can think of an historical crisis as a kind of conceptual “steroids” to boost your mind’s performance, but that effect will disappear once your anxiety does. Good philosophy - the kind of philosophy that lands you in the canon of History’s Great Thinkers - is a long, slow game. The West’s best known-philosophers have tended to live in times and places where they were able to think of major global developments - but from a distance. Aristotle built his school on the edge of the city so he could walk around in the first all day. Spinoza lived alone in a little cottage in the Hague. Kant’s habits were so regular people used to set their watches by his 4 PM walks. In medieval Europe, philosophy was largely the province of monks. Regularity and free time are the base elements that combine to form good philosophy, not stress. This, by the way, is why I am so, so dubious of rapid-fire “theory” responses to contemporary problems.

One thing worth noting in this context is that as with academic scholarship, and painting, and, for that matter, dance, only a tiny proportion of what is produced as and by “philosophy” will ever end up published, or read by anyone, much less remembered or RE-published or taught. And only a tiny proportion of that will be canonized and translated and transformed into elaborate critical editions. These minuscule proportions tend to stay the same even when more is being produced.

So what historical contexts do produce great philosophy? Well, as in the answer to the previous question, there are really two historically consistent factors.

The first and far more consistent one is this: philosophy tends to emerge under conditions where cultural, linguistic, and conceptual exchange is not only possible but encouraged, but that exchange happens under conditions of relative stability. So that in the history of Europe and the Middle East, at least, philosophy has tended to emerge not where there is upheaval but where there is both socio-economic stability and wide-spread cultural exchange. Ancient Athens; Alexandria in the first two centuries after Christ; Baghdad in the early medieval era; Toledo and Paris around 1000-1200 AD; Paris again in the 1960s; the Clinton ‘90s, where new domains of cultural exploration (queer culture, leather culture, Latino culture) became available to theorization during a period of economic prosperity. Trade, rather than war, tends to correlate with philosophical developments, though often that trade is preceded by imperial or colonial conquest, as in the example of Islamic philosophy in the medieval era or the philosophy of the later Enlightenment which corresponded to the rise of mercantile colonialism. In other words, the kind of exchange that promotes philosophical development is an exchange where you meet a foreign stranger who has something to teach you, but the two of you have to not try to kill each other long enough for that exchange to take place, or else you have to not both be running away from something together. Pretty straight-forward when you think about it. Put yet another way, trade without war can spur philosophy, but war without subsequent exchange rarely does. It wasn’t the conquest of Greece that led to the Roman fascination with Greek philosophy; it was the whole-sale importation of Greek intellectuals to serve as tutors and slaves in wealthy Roman households after the conquest of Greece. It wasn’t the expulsion of the Moors from Spain that led to the reinvigorated, multicultural Aristotelianism that emerged from Toledo in the later medieval era; it was the fact that, having expelled the Moors and taken their money and homes, the Christians now had time and space to read and translate all the books the Moors left behind. Cities at the center of inter-cultural trade (Baghdad, Amsterdam, New York) tend to produce philosophies, rather than cities at the center of monolithic, homogenous cultural spheres (St. Petersburg, Los Angeles, Madrid). The massacre and expulsion of the ethnic Greeks from Turkey after World War II, for example, produced some of the most painful poetry you will ever read but no great philosophy.

So that’s the first fact, and it more or less corresponds to the first factor in the previous question, which was “What is being taught?” When you meet new people from new cultures with new ideas, you find new things to think about and teach. The second factor in the previous question was “How easily available are the texts?” To that factor corresponds the second factor in this question, which is that in addition to cultural exchange under stable conditions, the other thing that facilitates new developments in philosophy are new developments in communication technology. The advent of the medieval scriptorium, the arrival of paper, the invention of the printing press, and electronic communication have all spurred new developments in thought, which makes sense: because communication technology affects how and where people can access texts, and access to texts is a major factor in the development or stagnation of a philosophical tradition.