Text

Hello Grambank! A new typological database of 2,467 language varieties

Grambank has been many years in the making, and is now publically available!

The team coded 195 features for 2,467 language varieties, and made this data publically available as part of the Cross-Linguistic Linked Data-project (CLLD). They plan to continue to release new versions with new languages and features in the future.

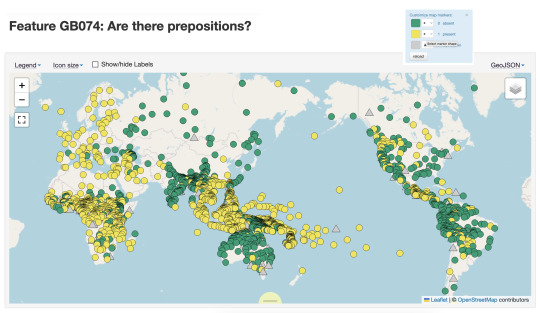

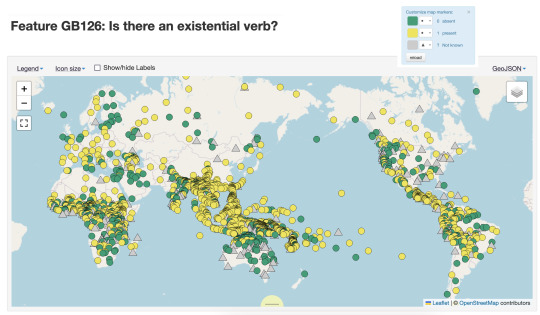

Below are maps for two features I’ve selected that show very different distribution across the world’s languages. The first map codes for whether there are prepositions (in yellow), and we can see really clear clustering of them in Europe, South East Asia and Africa. Languages without prepositions might have postpostions or use some other strategy. The second map shows languages with an existential verb (e.g. there *is* an existential verb, in yellow), we see a different distribution.

What makes Grambank particularly interesting as a user is that there is extensive public documentation of processes and terminology on a companion GitHub site. They also have been very systematic selecting values and coding for them for all the sources that they have. This is a different approach to that taken for the World Atlas of Linguistic Structures (WALS), which has been the go-to resource for the last two decades. In WALS a single author would collate information on a sample of languages for a feature they were interested in, while in Grambank a single coder would add information on all 195 features for a single grammar they were entering data for.

I’m very happy that Lamjung Yolmo is included in the set of languages in Grambank, with coding values taken from my 2016 grammar of the language. Thanks to the transparent approach to coding in this project, you can not only see the values that the coding team assigned, but the pages of the reference work that the information was sourced from.

431 notes

·

View notes

Text

A racist map of the world's languages

This post originates from the HWRG-blog. Please note that there are multiple authors of HWRG and that the most updated version of this blogpost can be found here: https://ift.tt/2YxniSr.

___________________________________________

A racist map of the world's languages

Detail of world map of languages and races from 1924.

The legend outlines language groups of the "yellow race".

In order to move forward towards racial and social justice as a discipline we must become familiar with our history and the ways in which racist, colonialist, sexist and classist ideas are still present in our academic spaces. I would like to present to you a concrete piece of evidence of our racist past in particular - a world-map where languages are grouped into three races: white, yellow and black.

I started writing this blog post several years ago, but ended up not posting it because I felt there was so much to say and I wasn't sure I was the right person to say it, nor able to cover all related content in a fair and accessible manner. With the recent publication of the article Toward racial justice in linguistics: Interdisciplinary insights into theorizing race in the discipline and diversifying the profession by Charity Hudley, Mallinson & Bucholtz in Language (and the responses and commentary), I felt inspired to share this map now - even if the post will be shorter than I had originally imagined. I think it is essential that we as linguist fully internalise that racism was not confined to a few fringe individuals, it was and is an ideology which permeates everything - including science and research.

Charity Hudley, Mallinson and Bucholtz outlines several steps which they believe linguistics as a disciple need to take in order to advance towards racial justice. One of them is:

Fully acknowledge the ongoing legacy of the field's history of racism and colonialism (Bolton & Hutton 2000, Errington 2001, Leonard 2018)

In the spirit of that, I'd like to talk about a Swedish map from 1924 depicting the languages of the world, coloured by language families and grouped into races.

This map is part of a set of maps which was made by the Swede Docenten Friherren Sten De Geer. They were published in an atlas by Åhlen & Holm AB for the Swedish Red Cross. The atlas was made to educate the general public of Sweden and Scandinavia about the world's countries and people.

The map in question is found on the lower part of the image below. The image contains two maps, the upper one depicts religions and the lower languages. All languages of the world are grouped into linguistic groups (such as Germanic, Bantu or Malayic) and subsumed under a super-category of race. For example, Germanic languages are of the "white race", Bantu "black" and Malayic are of the "yellow race".

I've included both a colour and black-and-white version for easier readability, and below I've translated the Swedish text into English. If you want to see a higher resolved version, go here.

________________________________________

Below is the text from the lower map of languages and races translated from Swedish to English by me. I've stayed as close to the original as possible, except in some cases where I use a more well-known English label for a category, for example "syrjänska" = "Komi".

________________________________________

Translation:

The white race's languages (Inflectional languages)

Germanic

Romance

- French, Spanish, Catalan, Italian and Romanian

- Portuguese

Slavic languages

Greek and Albanian languages

Iranian languages, together with Armenian and Caucasian

Hindu languages

Singalese (Hindi-Dravidian)

Latvian & Lituhanian

Celtic

Basque

Semitic languages

Hamitic languages

The yellow race's languages (Agglutinating languages)

Uralic languages

- Hungarian and Eastern Khanty

- Finnish, Estonian, Volga-Finnish and Sami

- Komi and Samoyedic

Altaic languages

- Turkic languages

- Mongolian languages

- Tungusic languages

- Japanese and Korean

- Chukchi languages

- Aino

Dravidian languages (spoken by negroid people)

Munda languages (spoken by negroid people)

Incorporation languages

- Indian languages

- Eskimo and Aleut

Stem-isolating languages

- Malay languages (including Polynesian)

Isolating languages

- Isolating

The black race's languages (prefixing languages)

Bantu (spoken by negroid people)

Other negroid languages

- Sudanese languages

- Hottentott and Bushman languages

- Papuan

- West-Papuan (Negrito language)

- Australnegro languages

________________________________________

There is a lot to say here, and I am sure I will not be able to cover it all. I do not have the accompanying information about the construction or design of the map (if it exists).

Let us start by making a few specific observations:

- Just so it is said: as far as I am aware, historical linguists at this time (1924) did not propose that they had linguistic evidence of the three race groups as meaningful linguistic units. If they did propose such a thing, it must have been with skin colour as the sole evidence - not the comparative method and vocabulary.

- The division of three races that the map makes, "white", "yellow" and "black", is probably influenced by the religious and racist researcher Georges Cuvier. He proposed that humans should be divided into three races, the Caucasian (white), Mongolian (yellow), and the Ethiopian (black). From wikipedia: Cuvier claimed that Adam and Eve were Caucasian, the original race of mankind. The other two races originated by survivors escaping in different directions after a major catastrophe hit the earth 5,000 years ago, with those survivors then living in complete isolation from each other. Cuvier categorized these divisions he identified into races according to his perception of the beauty or ugliness of their skulls and the quality of their civilizations.

Just.. sit with that for a while before we go on. Read it one more time.

- The creator of the map is himself struggling with the exclusive division of the languages into the three races, placing Dravidian and Munda languages under "yellow", but noting that they are spoken by "negroid people". I don't know what to make of that really, but it is noticeable.

- The level of granularity alone betrays a racist attitude. There is much more detail to the various sub-groupings of Indo-European languages, while the rest of the world is represented in far, far less detail. For example, most East Asian languages are included under the label "Isolating". "Isolating" is a description of the grammar of a language, not a genealogical group. Even though our understanding of the relationship between East Asian languages was not as advanced in 1924 as it is now, the category "Tibeto-Burman" did in fact exist. The map was made for a Scandinavian audience which may mean they expected finer detail closer to home, but even so the coarseness of categorisation outside of Europe is extreme. The lack of attention betrays a lack of care.

- Indigenous languages of Americas and Australia are lumped together into two respective groups even though they each consist of very large amounts of different languages families. For example, the category labelled "Indian" on the map encompasses 1,000+ languages of 160+ families. Contrast this with Europe and our 230-ish languages where we're even getting distinctions of lower genealogical subgroups. To call "Indian" a shit category is the understatement of the centuries, especially considering the level of detail in other areas. Perhaps you think they just didn't know better? The "grandfather of modern anthropology" Franz Boas published his first volume of the Handbook American Indian Languages in 1911 where he, among other things, described the diversity of the Americas and lists 55 families north of Mexico. So, knowledge and information existed. If one were to get the assignment to make a map of the world's languages, information existed which could be used. (You can read the introduction of that book here. It's a worthwhile read, Boas discusses race at great length.) Again, lack of attention shows a lack of care from the creator.

- The depiction of the distribution of indigenous languages of the Americas, Australia and Aotearoa (New Zealand). I take it that the intention of the mapmaker was to only show the most common language in a given place and that this is why most of these regions are depicted only with the colonial European languages, with pockets of "Indian languages" in the Americas, "Australnegro" languages in Australia and a small section of "Malay" languages in Aotearoa. These red and pinkish places which appear entirely conquered by European colonisers were in many cases multilingual. These are places where indigenous languages were spoken and are still spoken today. To make the choices to not depict these languages at all.. it is a choice that perpetuates the erasure of indigenous people.

Okay. I think I'll stop there for now lest my blood pressure gets too high. Feel free to leave more observations of this map in the comment section.

I think that there is a common misconception that racism was essentially something unique to Germany in the 1930's. Depictions of non-german Europe during the second world war often seems to entirely erase the racism we know was there (and still is). For science in particular, there is a great tendency to ignore the racist legacy of our disciplines and to fail to address its continuation and the impact it has on scholars and research today.

I am a Swedish white woman, I grew up in the university town of Uppsala. Uppsala was the Swedish centre of research into "race-biology" from 1922-1958. This involved the measurement of skulls and the production of research which aimed at providing the state with scientific justifications for "exact racial hygiene" and "rational population policy". I didn't know exactly what this entailed until I became an adult, but growing up I did know the location of "rasbiologiska institutet" - it's a local landmark and reference point still.

The welfare state of Sweden in the 50's and 60's was racist and supported by scientists. Antiziganism was particularly strong. In Scandinavia there is a group of Romani people commonly known as 'travellers'. They have lived there for over 500 years. We sterilised these people, and people which were deemed "slow of the mind" or otherwise genetically undesirable without their consent. This was explicitly done for the sake of "eugenic hygiene". This was legal and encouraged between 1934-1975. Approximately a total of 63,000 people were sterilised without consent. The peak was in 1947-48, i.e. after the war had ended.

The Swedish nation state has also abused the indigenous people of the land - the Sami. This involved among other things taking children from their families, hurting them physically and emotionally - robbing them of their past and ruining their future.

I can highly recommend watching the movie "Sami blood" which depicts this abuse. It features a particular scene, linked below, where the the northern regional school of Sami children get a visit from intellectual men from down south, from Uppsala. As the event was announced to the children, I distinctly remember thinking "oh fun that's where I from!" before half a second later it hit me: there is only one reason Uppsala men are visiting a school like this in the 1930's. They are there to measure these children, to collect data on their racial inferiority and justify their continued mistreatment.

youtube

Scene from the movie Sami Blood where the main character, Elle-Marja, is examined

and measured by visitors from the race-biology research centre in Uppsala.

There is another scene, which is perhaps even more relevant to us as linguists, where Elle-Marja meets a group of "well-meaning" white anthropology students in Uppsala. They pressure her to preform jojk, a Sami style of singing. It becomes clear that to them she is an ethnological curiosity - not a fellow teenager.

Abusive treatment of "undesirables", ethnic minorities and indigenous people is by no means unique to Sweden, but I believe many Swedes and people outside of Sweden know little of this. These events are not isolated, old or forgotten - they are recent and reverberates through to today. Forced sterilisation due to eugenic reasons were preformed in Sweden all the way into the 1960's and they were legal until 1975. The Canadian Indian Residential School system which abused ingenious children existed for over 150 years (1840's to 1996). The Australian government took indigenous children from their families from 1909 until 1969. The list goes on. Read more and let it all sink in. Learn whose land you live on and and the history of the place and the nation state there. These are stolen generations, this can never be undone. This is not old, this is recent. Let it become part of your world - because it already is. Wether you like it or not.

The map which prompted this post was published in 1924, a decade before the eugenic force sterilisation laws came into effect in Sweden. Extremely racist ideas were included in educational material for the general public without question. It was obvious, this is the way things are and this is what we should tell our children. There are three races, and here are their languages.

No only are these events more recent than you may like to think, racism is still around - also in academia. For this post, I focussed on events decades past and outside of linguistics. If you haven't already, go read the paper by Charity Hudley, Mallinsson and Bucholtz in Language and the following responses to learn more about race in linguistics as a discipline today.

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Online resources on linguistic typology and beyond

This post originates from the HWRG-blog. Please note that there are multiple authors of HWRG and that the most updated version of this blogpost can be found here: https://ift.tt/3e5tasC.

___________________________________________

Online resources on linguistic typology and beyond

Many Humans Who Read Grammars are also teachers of some kind, myself included. With the world-wide outbreak of COVID-19, most of this teaching is forced to be no longer in a classroom setting, but rather in a remote fashion. This comes with one benefit: if someone can tell it better than you, and a video of it happens to be on youtube, get your students to watch that lecture! So, please find some resources on linguistic typology & co below.

First up is a short list of youtube videos on linguistic typology and some related topics.

There is an entire MA course called 'Language Typology' from the Virtual Linguistic Campus (Uni Marburg). Here is a link to the Virtual Linguistic Campus, featuring many more lecture series on topics in linguistics. A set of mini-lessons in linguistic typology by Isabel Cooke McKay, including topics such as phonological typology, 'typology of force' (imperatives and interrogatives), and subordinate clauses, can also be found on youtube. Tom Scott has made some fun relevant videos, including on morphological typology and on some very useful grammar features that English lacks, see all of them here. Lastly, here is a short intro to linguistic typology made by yours truly, because none of the above really covered what I wanted to convey.

Five years ago, Hedvig wrote a post about two excellent educational videos about language history/evolution, one on Peter Whiteley and Ward Wheeler's project to map the evolution of Uto-Aztecan languages and one on How languages evolve by Alex Gendler. Here is another lecture on that topic by Michael Corballis.

Another cool video deals with Berlin and Kay's (1969) implicational hierarchy of basic color terms. The famous TEDx talk by Lera Boroditsky on linguistic relativism is here. As well as another TEDx talk on the same topic by Petrina Nomiko. There are a lot of other TEDx talks on linguistics, on a variety of topics, including on language endangerment and the importance of linguistic diversity.

Hedvig also posted earlier about the lecture sets from the Centre of Excellence for Language Dynamics (CoEDL) that can be found on iTunes Uni, among which is a set of lectures called 'Language shape' that deal with multilinguality, diversity, language documentation and description and a lecture series on Language evolution. Her original post describes how non-iTunes Uni-users can get access to them.

Another series of lectures can be found on this channel (mostly in Russian). A tonne of lectures on typological topics can be found on the Vidya-mitra channel, in a variety of languages, but I haven't really figured out how these are structured yet.

Here are some documentaries on language revitalisation:

Voices on the Rise: Indigenous Language Revitalization in Alberta:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-dtEujiPUE0 (Voices on the Rise, episode 1)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g0UH1IhBnNk (Voices on the Rise, episode 2)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YZgJ8TZ0Zs0 (Voices on the Rise, episode 3)

Karihwanoron: Precious Things (with Kanien'kéha/Mohawk subtitles)

Rising Voices / Hótȟaŋiŋpi - Revitalizing the Lakota Language see also the official website.

And there is a lot more to be found on youtube, also older stuff, like 'Why save a language' by Sally Thompson (2006).

This is some of the stuff that I will be assigning to my students - hit me with your best videos, podcasts, and other online resources below!

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

A decade of state-of-the-art quantitative methods in linguistic typology

This post originates from the HWRG-blog. Please note that there are multiple authors of HWRG and that the most updated version of this blogpost can be found here: https://ift.tt/2SFCxa0.

___________________________________________

A decade of state-of-the-art quantitative methods in linguistic typology

Some turning points in linguistic typology are easily recognised, such as the ground-breaking work by Joseph Greenberg on implicational universals entitled "Some universals of grammar with particular reference to the order of meaningful elements" (Greenberg 1963). Other turning points are less well-defined, less commonly associated with a single paper, or a specific typologist, team, or place. But there was definitely something in the water during, let's say, a period centred around 2010 – a change that we could call the quantitative turn in linguistic typology.

Linguistic typologists have long recognised that the languages of the world are related in various ways, most importantly, in nested arrays of hierarchical descent (genealogy) as well as in so-called Sprachbunds or linguistic areas (geography). For a long time, i.e. work reaching from Bell (1978) all the way to Bakker (2010), these interdependencies have been viewed as something of a nuisance, something to get rid of using sampling: Only languages from as many as possible different and independent genealogical and geographical units are included in one's study. Correlations and distributions are then assessed using contingency tables and statistical tests that evaluate differences in counts, most importantly, Fisher's Exact test and Pearson's chi-squared test.

Between 2008 and 2010 or so, something changed. Linguistic typologists started using methods that no longer relied on sampling techniques. (At least) three more advanced quantitative methods for linguistic typology emerged:

The Family Bias method, which estimates statistical biases in distributions of typological variables across and within language families (big families as well as small families, including isolates). The method is set out in Bickel (2013), but also in Bickel (2011) and (2015), and has a long history as an earlier manuscript (Bickel 2008) mentions talks given on the topic already in 2006.

Generalized linear mixed-effect models (GLMMs) and other regression models. These model a dependent or response variable in terms of independent or predictor variables and are widely used both in linguistics and outside it (Coupé 2018). The benefit for typologists is that there are various ways to include information on genealogy and geography in the analysis, in order to make sure that interdependencies between datapoints are not due to shared history or areality.

Phylogenetic comparative methods are a set of tools adopted from evolutionary biology, another discipline which studies the characteristics of entities with long and pertinent histories. These methods model the evolution and distribution of cross-linguistic data on phylogenetic trees. Their first application was Dunn et al. (2011), the famous paper on lineage-specific trends in word order universals.

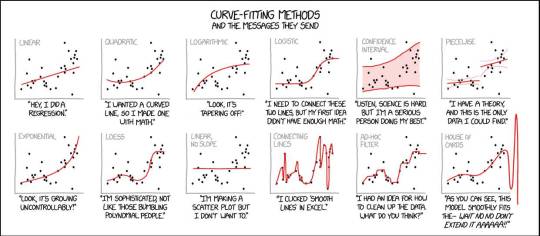

(c) xkcd

I'm not quite sure who first introduced regression models and later, generalized linear mixed-effect models for linguistic typology. Sinnemäki (2010) is certainly one of the first, in his 2011 dissertation he describes how he got the idea of regression modelling from a lecture by Balthasar Bickel in March 2008. Other studies employing regression models that came out around the same time are Cysouw (2010) and Bakker et al. (2011). Good examples of fruitful usage of these methods are Moran et al. (2012), who falsify the idea that there is a positive relationship between population size and phoneme inventory size first proposed by Hay and Bauer (2007), and Atkinson (2011), who proposes a negative relationship between phoneme inventory size and distance from West Africa. The latter paper triggered a lot of replies on the typological and sociolinguistic measures used in linguistic typology and appropriate statistics for evaluating interactions between them.

Out of these three methods, it seems that generalized linear mixed-effect models are now fast becoming the most widely used statistical tool on the typologists' belt, with a flurry of recent (recent meaning 2018/19) papers such as Gast and Koptjevskaja-Tamm (2018), Lester et al. (2018), Schmidtke-Bode & Levshina (2018), Sinnemäki & Di Garbo (2018), Schmidtke-Bode (2019), and Sinnemäki (2019). The most important one of these from a methodological perspective is Coupé (2018), who reports on the recent usage of generalized linear mixed-effect models but goes much further by introducing generalized additive models for location, scale, and shape for linguistic typology.

It's 2020! Palindrome Day has come and gone, and anyway – this year marks the first full decade after the the quantitative turn in linguistic typology. That is, if we want to put down the year 2010 for that – for sure it had been coming on for a few years in 2010, so feel free to argue with me on that. I think that it's absolutely wonderful that these methods are being used and developed further, and I hope to see this this particular element of doing typology flourish in years to come.

I also hope to have made the teeny-tiniest contribution to this flourishing by teaching a one-week course on quantitative methods in typology for LOT last month. We made an overview of pros and cons of these three methods (plus good-old-fashioned sampling) in class – so see below, there's your guide to your method-of-choice, depending how hard-core you want to go (Ben Bolker's GLMM disclaimers are always a nice way to come back down to earth).

References

Atkinson, Quentin D. 2011. ‘Phonemic Diversity Supports a Serial Founder Effect Model of Language Expansion from Africa’ Science 332 (6027): 346–349.

Bell, Alan. 1978. ‘Language Samples’. In Universals of Human Languages, Volume 1: Method - Theory, edited by Joseph H. Greenberg, Charles A. Ferguson, and Edith A. Moravcsik, 123–56. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Bakker, Dik. 2010. ‘Language Sampling’. In The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Typology, edited by Jae Jung Song. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bakker, Peter, Aymeric Daval-Markussen, Mikael Parkvall, and Ingo Plag. 2011. ‘Creoles Are Typologically Distinct from Non-Creoles’. Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages26 (1): 5–42.

Bickel, Balthasar. 2008. A general method for the statistical evaluation of typological distributions. Manuscript, University of Leipzig.

Bickel, Balthasar. 2011. Statistical modeling of language universals. Linguistic Typology 15. 401–414.

Bickel, Balthasar. 2013. “Distributional Biases in Language Families.” In Language Typology and Historical Contingency: In Honor of Johanna Nichols, edited by Balthasar Bickel, Lenore A. Grenoble, David A. Peterson, and Alan Timberlake, 415–44. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Bickel, Balthasar. 2015. “Distributional Typology: Statistical Inquiries into the Dynamics of Linguistic Diversity.” In The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Analysis, 2nd Edition, edited by Bernd Heine and Heiko Narrog, 901–23. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Coupé, Christophe. 2018. ‘Modeling Linguistic Variables with Regression Models: Addressing Non-Gaussian Distributions, Non-Independent Observations, and Non-Linear Predictors with Random Effects and Generalized Additive Models for Location, Scale and Shape’. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 513.

Cysouw, Michael. 2010. ‘Dealing with Diversity: Towards an Explanation of NP-Internal Word Order Frequencies’. Linguistic Typology14 (2–3): 221–34.

Dunn, Michael, Simon J. Greenhill, Stephen C. Levinson, and Russell D. Gray. 2011. ‘Evolved Structure of Language Shows Lineage-Specific Trends in Word-Order Universals’. Nature 473 (7345): 79–82.

Gast, Volker, and Maria Koptjevskaja-Tamm. 2018. ‘The Areal Factor in Lexical Typology’. In Aspects of Linguistic Variation, edited by Daniël Olmen, Tanja Mortelmans, and Frank Brisard, 43–82. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter.

Greenberg, Joseph H. 1963. ‘Some Universals of Grammar with Particular Reference to the Order of Meaningful Elements’. In Universals of Language, edited by Joseph H. Greenberg, 73–113. London: MIT Press.

Hay, Jennifer, and Laurie Bauer. 2007. ‘Phoneme Inventory Size and Population Size’. Language 83 (2): 388–400.

Lester, Nicholas A, Sandra Auderset, and Phillip G. Rogers. 2018. ‘Case Inflection and the Functional Indeterminacy of Nouns: A Cross-Linguistic Analysis’. In Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society.

Moran, Steven, Daniel McCloy, and Richard Wright. 2012. ‘Revisiting Population Size vs. Phoneme Inventory Size’. Language 88 (4): 877–893.

Schmidtke-Bode, Karsten. 2019. “Attractor States and Diachronic Change in Hawkins’s ‘Processing Typology.’” In Explanation in Typology: Diachronic Sources, Functional Motivations and the Nature of the Evidence, edited by Karsten Schmidtke-Bode, Natalia Levshina, Susanne Maria Michaelis, and Ilja A. Seržant, 123–48. Berlin: Language Science Press.

Schmidtke-Bode, Karsten, and Natalia Levshina. 2018. ‘Reassessing Scale Effects On Differential Case Marking: Methodological, Conceptual And Theoretical Issues In The Quest For A Universal’. In Diachrony of Differential Argument Marking, edited by Ilja A. Seržant and Alena Witzlack-Makarevich, 509–37. Berlin: Language Science Press.

Sinnemäki, Kaius. 2010. ‘Word Order in Zero-Marking Languages’. Studies in Language 34 (4): 869–912.

Sinnemäki, Kaius. 2019. “On the Distribution and Complexity of Gender and Numeral Classifiers.” In Grammatical Gender and Linguistic Complexity: Volume II: World-Wide Comparative Studies, edited by Francesca Di Garbo, Bruno Olsson, and Bernhard Wälchli, 133–200. Berlin: Language Science Press.

Sinnemäki, Kaius, and Francesca Di Garbo. 2018. “Language Structures May Adapt to the Sociolinguistic Environment, but It Matters What and How You Count: A Typological Study of Verbal and Nominal Complexity.” Frontiers in Psychology 9: 89–23.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ethnologue changes access, again! Clarifying points

This post originates from the HWRG-blog. Please note that there are multiple authors of HWRG and that the most updated version of this blogpost can be found here: https://ift.tt/36wndBx.

___________________________________________

Ethnologue changes access, again! Clarifying points

News in brief.

Ethnologue, as of October 26, have changed their access conditions on the site. Instead of getting 3 free page views per month, users can now see all pages on the website but not all information on them. To the right are examples of what the views look like for Country and Language pages.

They are also pushing more for their guide pages, which old users may notice is very similar to the "Statistics" pages of older editions. These guide pages seem directed more at educators than academics.

Just like with the previous access restrictions, these are not levied against users in certain countries with low mean incomes.

They have also launched a contributor program, which will enable people who contribute to access Ethnologue freely.

SIL International is the published of Ethnologue, they are a "faith-based" organisation and while they claim to not be missionary, they work closely with and are funded by their sister organisation Wycliffe Bible Translators who are explicitly Christian missionaries. You can read more about the finances of SIL International here.

SIL International are also the official registration authority for ISO 639-3 - the most popular of the ISO standards for language names & codes. It is hosted at a website separately from the Ethnologue and that website is not under any access restrictions. You can see all old change requests and updates to the classifications there.

See also our old blog post about the 2016 change.

Alternatives to Ethnologue

Ethnologue is a great resource that have served academics well for a long time, and the ISO 639-3 code standard is very practical. However, perhaps time has come for Ethnologue to redefined their target audience and for academics to go elsewhere. The limited information provided to non-subscribers is indeed very minimal, and it is not clear that Ethnologue offers enough added value compared to other resources to warrant asking your local university library to subscribe.

There are several other resources that provide similar services to Ethnologue, and of these Glottolog is the most comprehensive. Glottolog.org offers many of the same functionalities as Ethnologue and ISO 639-3. You can find the following information there:

Language classification (what counts as language versus dialect, by their standards)

Language codes for languages, dialects and families and all nodes in between (handy if you disagree with their classification in (1)

Language locations (points, not polygons)

Endangerment status and descriptive status per language

see Glottoscope and Glottovis for interactive visualisations

References per language

Alternative names

Below is a table comparing Glottolog and products by SIL International on more points:

body,div,table,thead,tbody,tfoot,tr,th,td,p { font-family:"Liberation Sans"; font-size:x-normal }

SIL International Glottolog Other resources Language codes Yes Yes (also for families and dialects)

Open Access? No, mostly behind paywall Yes, Open Access (CC-BY)

Alternative language names Yes Yes, including names from Ethnologue, OLAC, MultiTree, AIATSIS etc OLAC, MultiTree, WALS, AIATSIS Population stats Yes No

Language bibliography Yes, 42.000+ references Yes, 180.000+ references OLAC Endangerment information Yes Yes, but derived from Ethnologue and other resources (→) UNESCO Atlas of Languages in Danger, ELCat Descriptive status No Yes

Genealogies Yes, but not referenced Yes, and referenced MultiTree, D-place Phylogenies Language area polygons Yes, but not freely available (costs est 5.000 USD) No Partial: https://native-land.ca/ and others Countries per language Yes Yes

Long/lat point per language Derivable from polygons Yes

Genealogical classification tendencies Merge Split

Handling of contact languages Creoles, Pidgins and Mixed all in their own 3 separate families Creoles appear within their lexifier's family, pidgins and mixed in own 2 families

Handling of sign languages In their own family with no hierarchy In their own family with some hierarchy based on history and type

Handling of isolates All in one family Separated out (no Family_ID = Isolate)

Requests for changes Form at iso639-3.sil.org GitHub Issues

Transparency in decisions Changes in ISO 639-3 are mostly well described, most other information per language is not referenced. Almost everything is tied to a published reference

Dialects Yes, listed but not as meticulously managed as “languages” Yes, listed but not as meticulously managed as “languages”

Criteria for being a language Mutual intelligibility, shared cultural identity, shared literature Mutual intelligibility, lexical similarity

“Faith-based” Yes No

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

Language family maps

This post originates from the HWRG-blog. Please note that there are multiple authors of HWRG and that the most updated version of this blogpost can be found here: https://ift.tt/2BVeZVg.

___________________________________________

Language family maps

Last week, I assigned Bernhard Comrie's (2017) chapter 'The Languages of the World' (from The Handbook of Linguistics, 2017) to a class. It's a basic overview of the world's language families, which is what I wanted them to read, but for one thing: there are no maps in it. I overcompensated in class by presenting a 30-item list of maps, because some things are just so much easier to understand using visual representations. I decided to post some of the best ones I could find here, for future reference and in order to invite you to post better ones in the comments.

This blog has featured posts on maps before, by Hedvig on how to best represent linguistic diversity on maps and by Matt on new approaches to ethnographies-linguistic maps. It's clear that the kind of maps that are typically used to depict the spatial distribution of languages of a single language family are fraught with difficulties. Typically they deal with multilingualism very poorly, the data they display is usually from different sources that could be decades if not centuries apart, some maps below are based on ethnography and not on linguistics and how these line up is often not straightforward, the list goes on and on.

That being said, classification in terms of family membership is one of the primary means of classifying languages, and only through the history of language families we can understand how some languages have spread and others have died. Hence, the geographical perspective on language families is an important one. Here I am mostly after polygon maps of language families, and not maps per country (big on Ethnologue) or using points (to be found on Glottolog and LL-MAP).

During my search, I found that many handbooks do not feature maps (just one example, The Tai-Kadai Languages by Diller, Edmondson and Luo), which I found odd as it seems such an obvious thing to include. There is a lot of stuff to be find on the web, though. There are maps on the Encyclopaedia Britannica, unfortunately behind a paywall but many can be found online in a reasonable format, one is featured below on the Khoisan families, for instance. Muturzikin has polygon maps on continents and countries, so not specific to families, but of course in certain cases this doesn't really matter (like Australia). Then there are some blogs with collections of maps, such as Native Web and this older website.

Let's start with a journey around the world in language family maps, starting with Steve Huffmann's map of Africa:

Steve Huffmann's map of African languages using WLMS 16

Africa is home to the biggest language family of the world (in number of languages, at least currently): Atlantic-Congo, in Huffmann's map marked in shades of purple (non-Bantu branches) and green (Bantu). To the south of the Atlantic-Congo languages, we find the Khoisan languages (marked in shades of red on Huffmann's map):

Encyclopaedia Britannica's map of the Khoisan language families

And to the north, smaller families that were once subsumed under the family name 'Nilo-Saharan' (marked in shades of pink in Huffman's map), but which are now considered to be smaller, separate families:

Encyclopaedia Britannica's map of the Nilo-Saharan language families

Furthest to the north and also evident in the Middle East is Afroasiatic (marked in shades of light blue on Huffmann's map):

Encyclopaedia Britannica's map of the Afroasiatic language family

With these languages of Northern Africa, we arrive in Eurasia. One of the most wide-spread families of Eurasia is Indo-European. In the map below, the eastern part of Eurasia including India is not very well depicted at all, unfortunately.

Encyclopaedia Britannica's map of the Indo-European language family

The Caucasus Mountains and surrounding valleys are home to the Caucasian language families:

Map of Caucasian peoples, source: https://ift.tt/2Pso0xa

Even wider across the Eurasian continent than Indo-European stretches the Altaic language family, containing the Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic families.

Map on prior distribution of Altaic languages, from Bellwood (2013: 164)

Altaic has long been contested, but is now included in proposals on a language family termed Transeurasian, which includes Altaic as well as Korean and Japonic:

The distribution of the Transeurasian languages (Robbeets and Bouckaert 2018: 146)

In northern Eurasia, we find Uralic, which includes several big European languages, such as Finnish, Hungarian, and Estonian:

source: https://ift.tt/369hcua

At the very eastern end of the Eurasian continent, there is located the small family of Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages:

Map of the Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages and their neighbours, Fortesque (2011)

Here is a second, more colourful map showing the neighbours of the Chukotko-Kamchatkan family across the Bering Strait:

Map of the Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages and their neighbours, Krauss (1988)

Then we start slowly moving from Eurasia to South, East, and Southeast Asia. The Dravidian language family is located in the south-east of the Indian subcontinent, as well as in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Nepal:

Map of the Dravidian languages, Kolipakam et al. (2018)

To the north but very close to the Dravidian languages are the Munda languages, one of the subfamilies of Austroasiatic, which spreads all the way from the eastern Indian subcontinent to Malaysia:

Map of the Austro-Asiatic languages by Pinnow (1959), as cited by Sidwell (2009)

The Austroasiatic languages (also known as Mon-Khmer) are intermingled with a whole range of other families, including Indo-European and Dravidian in India, and Tai-Kadai, Hmong-Mien, and Sino-Tibetan in Southeast Asia. Sidwell (2009: 3-4) comments on how little is known regarding the internal relationships of the Austroasiatic, which must be so interesting given their dispersal and interaction with languages from other families. The following is a map of the Hmong-Mien language family from The Language Gulper:

Map of the Hmong-Mien language family from The Language Gulper

The following are two maps of the Tai-Kadai family, one from Encyclopaedia Britannica and one from Wikipedia:

Encyclopaedia Britannica's map of the Tai-Kadai language family

source: https://ift.tt/2BTMojh

This leaves us with the last huge family of the Eurasian continent, Sino-Tibetan. The first map is another map from The Language Gulper:

Map of the Sino-Tibetan language family from The Language Gulper

The second is a really nice map from Sagart et al. (2019), a recent study on the age of origin and the homeland of Sino-Tibetan:

Map of the Sino-Tibetan language family from Sagart et al. (2019)

For Austronesian, the second-largest language family of the world, there are various maps below. The first is from Bellwood (2013), displaying migration patterns. The second is a points map giving internal classifications on the basis of the phylogenetic analyses by Gray et al. (2009). The third I got from Hedvig and is a map of Oceania including Australia:

Map of population movements part of the Austronesian expansion from Bellwood (2013: 192)

Map on the Austronesian expansion from Gray et al. (2009)

Languages in Oceania by language family, courtesy of Hedvig Skirgård

As can already be seen in the map just above - the island of New Guinea is incredibly diverse, home to many Austronesian languages but also to the many Papuan language families. Muturzikin has a great map of these which is too big for me to copy here; what does fit is this map of the biggest of the Papuan language families, Trans-New-Guinea:

Map of the Trans-New-Guinea language family by Muturzikin

The same goes for Muturzikin's map of Australia, it's too big to copy here. Below is the beautiful map compiled by David Horton:

AIATSIS map of Indigenous Australia, compiled by David Horton

Muturzikin's map of Australia is a contemporary map, in other words it shows a patchy distribution of indigenous languages, surrounded by English. The same is true for some maps of the Americas. The following is a map of North America:

Map based on two maps by cartographer Roberta Bloom appearing in Mithun (1999:xviii–xxi), https://ift.tt/2N0CtPn

And the next two are two maps of Meso-America, the first displaying the linguistic situation at the time when Europeans first arrived in the area, the second (more or less) contemporary:

Map of Meso-American indigenous languages, source unknown

Map of Meso-American indigenous languages from The Language Gulper

The same applies to these next maps of South-America. The first map (kindly brought to my attention by Olga Krasnoukhova) presents the situation at some point in the past, the second presents a more contemporary view, showing the rate at which minority languages are dwindling and dying out.

Ethnolinguistic map of South America by Loukotka (1968)

Map of South American indigenous languages from The Language Gulper

I hope you enjoyed this trip around the world, limited though these maps may be. Please post better maps in the comments. If this post is a success, I will devote my next blog to isolates, languages with no known relatives. Enjoy!

References

Bellwood, Peter. (2013). First migrants: Ancient migration in global perspective. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

Gray, RD, A J Drummond, and S J Greenhill. 2009. “Language Phylogenies Reveal Expansion Pulses and Pauses in Pacific Settlement.” Science 323 (5913): 479–483. https://ift.tt/32SYdlD.

Fortescue, Michael (2011). "The relationship of Nivkh to Chukotko-Kamchatkan revisited". Lingua. 121 (8): 1359–1376. doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2011.03.001.

Kolipakam, Vishnupriya, Fiona M. Jordan, Michael Dunn, Simon J. Greenhill, Remco Bouckaert, Russell D. Gray, and Annemarie Verkerk. 2018. “A Bayesian Phylogenetic Study of the Dravidian Language Family.” Royal Society Open Science 5: 171504.

Krauss, Michael E. (1988). Many Tongues - Ancient Tales, in William W. Fitzhugh and Aron Crowell (eds.) Crossroads of Continents: Cultures of Siberia and Alaska (pp. 144-150 ). Smithsonian Institution.

Loukotka, Čestmír. (1968). Johannes Wilbert, ed. Classification of South American Indian languages. Los Angeles: Latin American Center, University of California.

Mithun, Marianne. (1999). The languages of Native North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Robbeets, Martine, and Remco Bouckaert. (2018). “Bayesian Phylolinguistics Reveals the Internal Structure of the Transeurasian Family.” Journal of Language Evolution 3 (2): 145–62. https://ift.tt/31XHuw0.

Sagart, Laurent, Guillaume Jacques, Yunfan Lai, Robin J. Ryder, Valentin Thouzeau, Simon J. Greenhill, and Johann-Mattis List. 2019. “Dated Language Phylogenies Shed Light on the Ancestry of Sino-Tibetan.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. https://ift.tt/36iEOMS

Sidwell, Paul. (2009). Classifying the Austroasiatic languages: History and state of the art. München: LINCOM.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

ALT2019 conference report

This post originates from the HWRG-blog. Please note that there are multiple authors of HWRG and that the most updated version of this blogpost can be found here: https://ift.tt/2Qa5sDP.

___________________________________________

ALT2019 conference report

Two weeks ago, the 13th Conference of the Association for Linguistic Typology (ALT) took place in Pavia, Italy. As the name says, this is the main gathering for members of the Association for Linguistic Typology, and it's on a different continent every two years. It just happened to be in Europe as I was ready to go conferencing again (now dragging two kids in tow) so that was lucky.

I like ALT a lot because I can go to basically any talk and find myself interested in it. There are hardly any talks or posters where I am disappointed because it isn't really my cup of tea - it's all typology so everything is my cup of tea :)! It is where the humans who read grammars gather. This year, ALT was paired with a summer school on 'Language universals and language diversity in an evolutionary perspective', which I would have loved to attend (but, kids).

For the first time in history (as far as we could find), ALT offered child care. About 5 attendees made use of this (and so the next generation of linguists are already networking ;)), in my case it really helped to attend some talks and give our own. Unfortunately I couldn't attend as many talks as I wanted, but as a logistic experiment it was mostly a success. Below I'll feature some talks I attended and others I wanted to attend but didn't, so you can read a bit about the latest & upcoming work in typology.

The first talks I managed to attend where those by Kirsten Culhane ('A typology of consonant/zero alternations') and Erich Round ('Canonical phonology'), both part of the workshop on 'Current research in phonological typology'. Culhane's talk argues for a more typologically informed analysis of consonant insertions and deletions, especially considering phonological and morphological conditions. Round's talk explained in detail why phonologists invariably diverge in their analyses of particular aspects of phonology, and how this can be avoided using a canonical approach.

Later that day, I wanted to attend Denis Creissels' talk on 'Cross-linguistic tendencies in the encoding of experiencers in the languages of Sub-Saharan Africa, and possible typological correlations' but I had to leave because the older kid wouldn't shut up - which several people found very funny.

The final day of the conference I was finally able to see some more talks. First, Kilu von Prince et al. ('Realis and irrealis in Oceanic'), who argued how the realis vs. irrealis distinction is relevant in Oceanic and probably also outside it (see here for the slides). Then, Jeff Good et al. with a more methodological talk on 'Individual-based socio-spatial networks as a tool for areal typology'. They presented extremely fine-grained data on language competence of individuals in a highly multilingual region, integrating linguistic, social, and geographic data (see picture below). Then, Dmitry Idiatov and Mark van de Velde ('Single feature approach to linguistic areas: labial-velars and the prehistory of the Macro-Sudan Belt') spoke about how labial-velar stops might be a characteristic of the now disappeared indigenous languages of West and Central Africa, whose speakers have shifted to various Niger-Congo languages.

Then it was time for our own talk ('Testing Greenberg’s universals on a global scale'), which was suffering a bit in attendance because in one of the parallel sessions, Nikolaus Himmelmann was speaking about 'Against trivialising linguistic description, and comparison'. In the abstract he had written 'In fact, Haspelmath’s approach to comparative concepts trivialises crosslinguistic comparison by elevating the pragmatic approach to grammatical comparison apparently required when compiling resources such as the WALS (Dryer & Haspelmath 2013) to the only proper methodology in crosslinguistic comparison. There are other, more rigorous and methodologically superior approaches to comparison, ...' so I guess people went to see what would happen during question time as Martin Haspelmath was attending. I am told there was some interesting discussion.

I missed a lot of cool new talks :(, in alphabetical order:

Chundra Cathcart et al.'s talk on numeral classifiers and plural marking in Indo-Iranian, showing that there is some evidence for the hypothesis that numeral classifiers develop more often in languages without plural marking;

Francesca Di Garbo's talk showing that in Cushitic and beyond, plural agreement can be dependent on lexical-semantic properties of the noun;

Jessica Ivani & Taras Zakharko's presentation of Tymber;

Gerhard Jäger's talk on Differential Object Marking and Differential Subject Marking investigated using hierarchical Bayesian modelling. This can be seen as a follow-up to work by Balthasar Bickel et al. and Karsten Schmidtke-Bode & Natalia Levshina that is interesting to follow because all three author sets use different methods and have different outcomes;

Olga Krasnoukhova & Johan van der Auwera's talk on the diachrony of a rather curious source of standard negation in certain languages;

Natalia Levshina's talk on the range (narrow vs. wide) that basic grammatical relations have and how this range can be investigated using corpora, showing that Finnish is the most extreme 'tight-fit' language, while Chinese and English are the most extreme 'loose-fit';

Ilja Seržant's talk on the lengths of person-number affixes of verbs, finding no evidence for Gívon's cycle (where indexes demise via phonological attrition and new indexes are formed through free personal pronouns);

Manuel Widmer et al.'s talk on the evolution of hierarchical person-marking systems in Tupian and Sino-Tibetan, showcasing the differences and commonalities of these systems in the two families.

Another thing I missed was the business meeting, which was sad because they are usually quite enjoyable - so know I don't know where ALT will be in two years time. If you do, please post a comment!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

My ELAN workflow for segmenting and transcription

This post originates from the HWRG-blog. Please note that there are multiple authors of HWRG and that the most updated version of this blogpost can be found here: https://ift.tt/2Oi4lkt.

___________________________________________

My ELAN workflow for segmenting and transcription

Hello everyone,

Hedvig here. I'm currently writing up my PhD thesis, hence the lack of writing here. Hopefully I'll be able to pick it up after submission, there's a lot of drafts lying on blogger waiting for completion. If you really, really miss me in particular, you could listen to my ramble at Talk the Talk - a weekly show about linguistics.

Now that the shameless plug and excuses are done with, let's get down and talk about:

THE TRANSCRIPTION CHALLENGE!

In this blog post, I will focus on a part of this challenge¹ - the workflow for segmenting and transcribing audio material. This is a rough guide, if it turns out people appreciate something like this I'll re-write it more thoroughly.

Anyone who has done fieldwork that involves interviews, be they video or audio, will know how time consuming it can be to segment and transcribe data.

Estimates of the factor involved here vary, depending on recording quality, the number of speakers involved, etc. Factors smaller than 10 (i.e. ten minutes are necessary to transcribe and translate one minute of recording) are rarely mentioned, and factors as high as 150 and higher are not unrealistic in the case of complex multiparty conversations. (Himmelmann 2018:34)

That's a lot of time, and often times there is no way around it, in particular if you're dealing with a language that has little description.

This challenge isn't only relevant to linguists, but also pertains to anthropologists, historians, journalists and others who need transcription. For journalists and historians, they often interview people in major language like English or Spanish and there's a tonne of software out there for automatic transcription. There's so much, that Adobe has even developed what they call "Photoshop for Audio" alongside their transcription services.

There even exists initiatives to bring this kind of automatic transcription technology to smaller languages. Check out the Transcription Acceleration Project and their tool Elpis here. But even Elpis needs to start with some manually transcribed audio, some training data. So, how do we get nice transcribed data in a timely fashion?

Most linguists who do fieldwork start out using ELAN for transcription. ELAN is a free software from The Language Archive that's fairly easy to use and provides a large amount of functions relating to segmenting and transcribing your data, both audio and video. ELAN is great, don't get me wrong, and this guide will be based on using ELAN. However, the program has a lot of different options and people use it very differently - this can be overwhelming for beginners and it can be difficult to figure out how to optimise it for what you need to do.

Different linguists often develop their own "ELAN-style", and since the workflow (and often also the transcription data itself) isn't shared with people outside of your project- there is little dissemination of these different ELAN-styles. Some people have even described learning ELAN as an apprentice type system, where you may learn the ins and outs by working for someone else first before you start on your own data. If you're attending a linguistic fieldwork class that teaches ELAN, you'll probably be introduced either to your instructors personal ELAN-style, or one of the styles that TLA suggests in their manuals. That can be great and if it's working well for you, awesome! However, it may be that there is some fat to trim of your current ELAN-workflow. I'll share a basic outline of my workflow here, and perhaps you'll find some trick that can improve you workflow too!

My ELAN workflow

Main take-away: you don't need to segment by hand and you don't need to listen through the recording several times for each speaker in order to get speaker separated tiers. The fact that you can export (and import) your ELAN transcription into regular tsv-files can save you a LOT of time and energy.

Caveat: This guide will be rather schematic, if it turns out that this is useful for people I can develop it in more detail later. If you want that to happen, drop a comment on the blogger-blogpost. I have actually basically already described this workflow in two separate blogposts, I'm just brining them together here for a start-to-finish-flow.

Assumptions: you have audio and/or video files of semi-natural conversations where most of the time one person is talking at a time, even if there is some overlap. You want to have it segmented into intonational unites, transcribed, translated and you want to separate out who is speaking when. You have downloaded and installed ELAN and mastered how to create ELAN files and associate them with audio/video-files.

Don't worry about separate speaker/signer tiers: In this workflow, we're going to start out with transcribing all speakers/signers on one tier. If you want them separated out into different tiers, we have an option for that later. Don't worry, it'll be fine. If you have a large amount of overlapping speech or sign utterances and you want them all transcribed separately, you can still use this guide but you'll have to go over the steps for each speaker/signer/articulator. If that is the case, this guide may not be that much more effective than what you're already doing, but let me know if it is.

Caveat 2: I don't make use of "tier types" and their attributes at all in my ELAN-use. I just use the basic time-aligned default tier type. I haven't yet encountered a situation where I really need tier types. It may be that the project your in cares about tier types, if so do make sure that you obey those policies. If not, don't worry about it.

The steps

1) Create two tiers, call them:

segmentation by utterance

larger segments (optional)

2) Make sure you know how to switch between different modes in your version of ELAN on your OS. We're going to be using the annotation, segmentation and transcription modes.

3) Segment "empty chunks" tier into annotations. Either:

a) Automatic segmenting via PRAAT (see blogpost here)

b) the "one keystroke per annotation; the end time of one annotation is the begin time of the next. This creates a chain of adjacent annotations" segmenting option in ELAN.

Tap whenever you think an intonational utterance has reached its end. If there are pauses, just tap it into smaller chunks. Annotations with silences aren't a big problem, they will just have no transcription in them later so we can remove them automatically then if need be. They can be a bit annoying, but they're not a major problem really.

You may want to adjust the playback speed while segmenting or transcribing. If someone is talking very slowly and going through an elicitation task with clear pauses, you may be able to segment at a higher speed.

Trivia: it seems like intonational units are quite easy for humans to detect, so much so that speakers of German were able to fairly successfully segment Papuan Malay despite not knowing any Malay

4) Larger segments-tier

If you have several events happening in one recording (say a consent confirmation, a wordlist and a narrative), then you may want to keep track of this during step 3. Either select to only chunk the events you need, or at least make note separately on a piece of paper when an event started and ended if your using 3b. Use that information to create really long annotations in the larger segments tier for each of the events. Alternatively, use the information in the transcription tier later to generate annotations in the larger segments-tier, for example if you know the first and last word of the wordlist you're using.

5) Make copies of the segmentation by utterance-tier with empty annotations and call them

Transcription

Translation

Speaker/signer/articulator²

Comment

These will be exactly time aligned with each other, and this is important. Make sure that any obvious goofs in the empty chunks tier are taken care of before you duplicate it.

Keep the empy tier around, you might need it later.

6) Transcription. Switch to transcription-mode. Show only the 4 tiers from step 5.

If you have different people transcribing from translation, select only the tiers that are relevant for that person. Turn on automatic playback and loop mode. Make sure that each person has their own comment tier, and encourage them to write things there while they're transcribing if there is something they want to quickly note.

Make sure you have set clear rules for how to deal with false starts, humming, laughter, backchanneling noises etc. Do you want all of those transcribed? If so, do you have a short hand symbols for them? Make sure you're clear about this early on, especially if you have multiple people working on transcribing the data.

In the speaker/signer/articulator tier put down the appropriate initials of the person/articulator.

Since I don't use tier-types, I can't use the column mode. I don't really mind, but if you prefer using the column set-up then you need to assign the 4 different tiers to different tier types.

If you only want to transcribe a certain event, either only chunk that event in step 3b and not the others. Or go back to annotation mode, write "blubbi" in the first segment on the transcription tier within that event, go back to annotation mode and scroll down until you see "blubbi". Not the most elegant solution, but hey it works.

Leave the silence annotations entirely blank.

7) Overlaps!

Now, you may have overlapping speech/gesture/sign at times. The first thing you need to do is ask yourself this question: do you really need to have all of the overlaps separately transcribed? For example, if it's very hard to make out what one person is saying in the overlapping speech, how valuable is it to you to attempt to transcribe it? It may very well be that the answer is "yes" and "very valuable", and that's all good. Just make sure that this is indeed the case before you go on.

It is entirely possible that you don't want to transcribe instances of overlapping utterances, if that is the case you can stop here and just leave your file in the stat it is in. You can still tease out who is speaking when. The main reason to separate out speakers into separate tiers it to handle overlap, and if you don't care about that you can actually just stick with having all speakers merged on one tier. It will actually probably be easier for you in the long run. I don't do step 8 and 9 normally, but I have figured out how to do them so that if I ever wanted to/was made to - I can separate out speakers.

If you do want to tease them out here's what you do. During step 6 put down the initials of all the people talking at the overlapping annotation in the speaker/signer/articulator tier, write "overlap" in comment tier and leave the other 2 tiers blank. That's it, for now.

8) Separating out the tiers into separate for speaker/signer/articulator

Now we should have an eaf file with transcription & translation for all of the non-overlapping annotations, including information about which person is associated with which annotations and where there is overlap (and who speakers/signs in that overlap).

What we're going to do now is basically make slimmed down version of what we did here. In that guide, we did a clever search within ELAN, exported the results of exactly that search only and imported those results as a new tier. The new tier was merged into the old transcription document, and voila we've got an extra new tier with only the search results. This is useful for example if you want to listen through only words transcribed with [ts] clusters to see if they are indeed realised as [ts] or sometimes as [t]. The same principle also works here where we want to separate out annotations associated with certain people.

We're going to

a) export all of the tiers and all annotations

b) make copies of the exported files and prune each of them to only the annotations that pertain to a certain speaker

c) import those files as new transcription documents

d) merge those with the original file

a) export transcription

Within ELAN, export the entire transcription document as a tab-delimited text file. You do this under File> Export as.. > tab-delimitated text file. Tick "separate columns for each tier".

Name your file something sensible, and put it in a good place. The file will have the file-extension ".txt", but it is a tab-separated file (".tsv"). Rename the file so that the suffix is ".tsv". Open the file in some spreadsheet program (excel, numbers, libreoffice, google sheets, etc). I recommend Libreoffice, because it let's you explicitly set what the delimiters and endcoding are, whereas excel makes a bunch of decisions for you that may not be ideal.

Now, since your annotations are time aligned we get them all on the same row. Here's a little example of what it looks like in my data:

Starttid - hh:mm:ss.msStarttid - ss.msekSluttid - hh:mm:ss.msSluttid - ss.msekTidslängd - hh:mm:ss.msTidslängd - ss.msekLarger segmentsSegmentation by utteranceSpeakerTranscriptionTranslationComments00:17:56.4501076.4500:20:56.7851256.78500:03:00.335180.335Heti's spectial wordlist

00:22:28.4001348.400:27:54.9001674.900:05:26.500326.5

00:00:02.4492.44900:00:04.0724.07200:00:01.6231.623

00:17:58.7601078.7600:18:03.7031083.70300:00:04.9434.943Heti's spectial wordlist

Mo se tane lelei e fa'a fa'aaloalo le a:vaa good husband repect his wife

00:18:03.7031083.70300:18:06.6631086.66300:00:02.9602.96Heti's spectial wordlist

T.. tane tane tanehusband

00:18:06.6631086.66300:18:09.0551089.05500:00:02.3922.392Heti's spectial wordlist

Mo le ga . koe faikau uma ais that it . read all of this

00:18:09.0551089.05500:18:16.2631096.26300:00:07.2087.208Heti's spectial wordlist

Mo fea le le manu .. na ou va'ai ai ananafiwhere is the bird i see yesterday

00:18:16.2631096.26300:18:18.6951098.69500:00:02.4322.432Heti's spectial wordlist

Mmanu manu manubird

00:18:18.6951098.69500:18:24.0381104.03800:00:05.3435.343Heti's spectial wordlist

M... o namu e pepesi ai fa'ama'i namosquito spread disease

b) filter the rows

Now, by just using the simple filter functions in most spreadsheet programs, we can make new files that only contains the rows with certain speakers in it. Make a few copies of your tsv file, call them "speaker x", "speaker y" etc. In each of those, filter for all of the rows you want to delete, and delete them - leaving only the rows with the relevant speaker. In the example below, I'm filtering for all the rows where the speaker isn't "M" and deleting those.

c) import filtered tiers into ELAN

Now we go back to ELAN and we import the files as tiers. What will happen here is that a entire new .eaf-file will be created, the tier will actually not be imported directly into whichever file you currently have open. This means that it doesn't matter which .eaf-file you currently have open when you import (or indeed if any is open). Counterintuitive, I know, but don't worry - I've figured it out. It's not that complicated, just stay with me.

For this to work, the file needs to have the ".txt" suffix again.

File>Import> CSV/Tab-delimited Text file

Importing CSV/Tab-delimited Text file

Next up you will get a window asking you questions about the file you're trying to import, make sure that it lines up with the little preview you get.

Import CSV/Tab-delimited Text file dialogue window.

I wish that ELAN had a way of automatically recognising its own txt-output, but it doesn't. No need to specify the other options, just leave them unchecked.

An actual ghost

Now you will have a new .eaf-file with the same name as the file with the pruned results.

This file will only contain the annotations that matched your filterings. There's no audio file and no other tiers. It's like a ghost tier, haunting the void of empty silence of this lonely .eaf-file.

A lonely ghost tier in an otherwise empty .eaf-file

Save this file and other files currently open in a good place, quit ELAN and then restart ELAN. Sometimes there seems to be a problem for ELAN to accurately see files later on in this process unless you do this. I don't know why this is, but saving, closing and restarting seems to help, so let's just do that :)!

Chris O'Dowd as Roy Trenneman in IT-crowd

d) importing the search results tier into the original file

Now here's where I slightly lied to you: we're not going to import the tier into your file. We're going to merge the pruner speaker-only-file with the other .eaf -file that has all the audio and other tiers and the result is going to be a new .eaf-file. So you'll have three files by the end of this:

a) your original .eaf-file with audio and lotsa annotations

b) your .eaf-file with only the search results-tier and no audio etc (ghost-tier)

c) a new merged file consisting of the two above combined

Don't worry, I've got this. I'm henceforth going to call these files (a), (b) and (c) as indicated above.

Open file (a). Select "Merge Transcriptions..."

File>Merge >Transcriptions...

Select Merge transcriptions

Now, select file (a) as the current transcription (this is default anyway), file (b) as the second source and choose a name and location for the new file, file (c), in the "Destination" window. You can think of "Destination" as "Save as.." for file (c) - our new file.

Specifying what should be merged and how

Do not, I repeat, do not append. And no need to worry about linked media, because (b) doesn't have any audio or anything (remember, it's a ghost). Just leave all those boxes unchecked.

Let ELAN chug away with the merging, and then you're done! You've now got a eaf file with separate tiers for separate speakers.

9) dealing with the overlap

Now, when you're at step 8b and you're filtering for people, make sure you including the overlapping speech for that person in that file. You're going to have to go back to that tier and search for the instances where you have "overlap" written in the comments and manually sort things out. There's no automatic way of dealing with this this I'm afraid, you're going to have to delete the annotation and make new ones that line up across the tiers for that speaker. Go to annotation mode, hide all the other tiers, keep only the ones for that speaker. Navigate to the overlap by searching, delete the existing annotations in that region, highlight new appropriate time intervals and right click each tier and select "new annotation here". This will give you new aligned annotations intervals that you can now deal associate with just one speaker.

DONE!

If you're curious how to use this technique but for matching particular searchers, read this blogpost

If you found this useful and want be to write it up a bit more neatly and with more screenshots etc, let me know in the comments. There should be a way of making this work better with python, but I haven't figured that out just yet.

Good bye!

¹ Himmelmann wrote a paper about this challenge, and he says that the actual challenge is "reaching a better understanding of the transcription processitself and its relevance for linguistic theory". We're not going to be doing that here, but please read his paper if this challenge is something that interests you.

² Articulators are relevant for sign languages and gesture transcription, and this guide actually can fit transcription of speech as well as sign and gesture, including transcribing different articulators on different tiers.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

That infographic, again ;)

This post originates from the HWRG-blog. Please note that there are multiple authors of HWRG and that the most updated version of this blogpost can be found here: https://ift.tt/2Qm6w3a.

___________________________________________

That infographic, again ;)

In 2015 I wrote a blogpost about Alberto Lucas López visualisations of the worlds languages. I answered some frequently asked questions in relation to that visualisation, mostly to do with Ethnologue's definitions of languages, macro-languages and speakers. There's a lot more context needed to fully understand that infographic, and every time I see if re-shared I see the same questions pop up. It's a good infographic, so I understand that it goes viral - but when the same questions come every time it means that more context is needed.

Since then, Alberto (who is now Senior Graphics Editor at the National Geographic) has released an updated version, which among other things fixes the color of Mexico. I haven't gone through to check what else has been adjusted, but many of the same questions will remain. This is because Ethnologue's classification of what is and what is not a language (which still underlies the visualisation) is still controversial at times and the general public will not known what Ethnologue and the Library of Congress mean by "macro-language".

I might do another blog post going through the visualisation, if there's enough new questions. Post them here or at the old post if you have any :)!

Over and out,

Hedders

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brust, breast, borst: an encounter with r-metathesis

This post originates from the HWRG-blog. Please note that there are multiple authors of HWRG and that the most updated version of this blogpost can be found here: https://ift.tt/2MfmObj.

___________________________________________

Brust, breast, borst: an encounter with r-metathesis

Two months ago I gave birth to our second daughter. In order to prepare for this joyous event, I prepared by trying to get some of the local (German) vocabulary on labour & babies in my head. One of the words I had some trouble with was Brust 'breast'. Basically, my German reading is pretty decent, but speaking and writing are another matter, I just don't have enough vocabulary at the ready, hence my quest. Until now I could get away with blaming my high school education, where I suffered from a then new policy to split up second language education in a compulsory reading module and an optional speaking & writing module that I did not take. Having lived in Germany for over two years now, it's getting rather embarrassing though.

Anyway, back to Brust. The reason I found it confusing is that compared to my native Dutch, the r is in the wrong place: in Dutch it's borst 'breast'. Hmm. English breast has the r in the same place as German though. Then when I was brushing my teeth one night, I realised borstel 'brush' in Dutch looks a lot like Bürste 'brush' in German, and also to the English form brush, now with English having the r in the 'wrong' place. What's going on here?

Food items that look like breasts, no. 1

This phenomenon is called metathesis, when sounds or syllables in a word or, when dealing with sentences, words in a sentence, change their order. Specifically we are dealing with r-metathesis here, the position of r has been changed to come after the vowel in Dutch borst 'breast' - as for brush, we'll come to that. This is a really common type of sound change, and many examples are given on a wikipedia page here.

In the words for 'breast', it's Dutch borst that's the odd one out: all the Germanic forms have the br cluster and go back to Proto-Germanic *breust-, *brusti- 'breast', which ultimately goes back to Proto-Indo-European *bhreus-, *bhreu-, with meanings ranging from 'breast' to 'belly' (see here). The only exception is West Frisian boarst 'breast', from Old Frisian briast, brast - one can only imagine this instance of r-metathesis must have occurred under pressure from Dutch.

Food items that look like breasts, no. 2

As for the words for 'brush', turns out they are not all related. English brush is a loanword from Old French broisse, while Dutch borstel and German Bürste come from the Proto-Germanic form *burstila-, a diminutive of *burst 'bristle'. These forms come from a word meaning something like the hair that sticks up on certain animals, as brushes used to be maid from wiry animal hair. Actually, the Dutch and German words are related to English bristle, where it's actually English that has undergone the r-metathesis (see here and here).

Just as a bonus, another word I learned and was confusing too, but because of very different reasons, is Kreißsaal. kreißen is a verb meaning 'to labor', and saal means 'room', so together it's 'delivery room'. My immediate association though is with the cognate Dutch verb krijsen 'scream, screech', so for me Kreißsaal translates to 'screaming room'! When I explained this to native German speakers they seemed rather surprised at this. Turns out the verb kreißen seems rather uncommon in contemporary German ('only' 36.700 hits on Google). One of my friends told me her only association of the first part of the word was with Kreis 'circle', and she thought that for some reason, all delivery rooms were circular well into adulthood.

So far for baby-related adventures in German, I promise to talk about grammar next time.

Food items that look like breasts, no. 3

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Having fun with phrase structure grammars: Midsomer Murders and Beatles