Text

Hello everyone, and welcome to an educational post about dinosaur bones!

I’ve mentioned in a post before how sometimes structures like feathers can fossilise under the right conditions. This is how we know many dinosaurs had feathers, including microraptor, archaeopteryx, and sinosauropteryx. But there are actually a few other ways to tell a dinosaur had feathers, which I hope to explain in some of my posts- one of which we will be going over today.

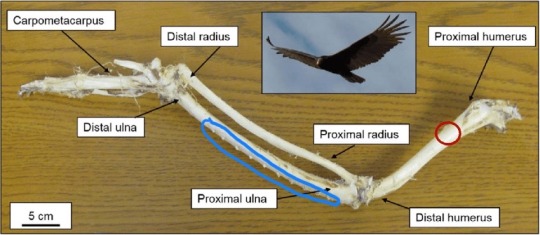

First of all, we’ll have to look at the skeleton of a modern bird.

Not sure how readable the text is, but I’ve marked out a bone there called the ulna for you. Let’s get a closer look.

Ignore the red circle, that’s not mine. The blue circle is what you’ll gotta look at- you’ll see small bumps coming off the ulna. These bumps are called quill knobs, and they’re actually where the feathers attach to the bone- signs of the existence of feathers without a shred of actual feather.

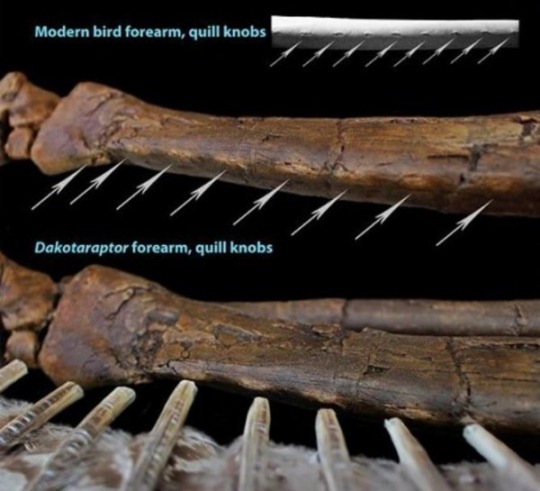

And, as you might have guessed, the ulna of modern birds are not the only ulna you can find quill knobs on.

They’re a little harder to see- sorry, I’m trying my best to find good images, but finding good pictures is literally the hardest part of running this blog- but these are quill knobs on the ulna of a dinosaur called dakotaraptor. Dakotaraptor was a beautiful and formidable relative of velociraptor. We can infer from the quill knobs and from related fossils that it had a winglike structure on its arm, that may have functioned to keep it balanced while pounced on prey or to help it run up steep slopes by giving it some lift.

Here’s a visual. Credit to the Saurian team for this beautiful image.

The ulna isn’t the only place we can find quill knobs, though. We can and have found them on the tail of many dinosaurs. I wish I’d have found an image, but all I found was that amber study I need to look into. Instead, here’s an image of the structure the quill knobs were there to support- the tail fan. Image credit to Ripley Cook.

We have found quill knobs on many dinosaurs, especially raptors like dakotaraptor. We know from a combination of quill knobs, fossilised feathers, and phylogenetic bracketing (a methodology I will go over another day) that dromaeosaurs (raptors), oviraptors, therizinosaurs, troodontids, and ornithomimosaurids (dinosaurs like gallimimus) all had birdlike feathers. Compsognathids and many tyrannosaurs also had feathers, but not the birdlike kind- they had proto-feathers that more resembled fur.

I will also note that there is a debate over whether a dinosaur called concaventor has quill knobs. I will not go into that here because I don’t want to post about something so contentious that I haven’t looked into at all, but it is worth noting that the discussion exists. Go look into that if sifting through niche studies is your idea of a fun afternoon.

To close, I’d like to ask everyone who’s read any of my posts to give me feedback. Do I dumb everything down too much or is it too complex? Is my formatting no good? Please give me your thoughts, I love teaching people new things but I’m not sure if I’m any good at it.

And once again, I hope you all enjoyed being educated, and have a great afternoon!

428 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello everyone! Welcome to an educational post about pterosaurs!

I’m a massive fan of pterosaurs, so I always get sad when they’re misrepresented in media, and they almost always are. So today I’m going to clear up some misconceptions about pterosaurs, as well as take you guys through some different species that I find interesting.

Art credit: Chase Stone

Firstly, what are pterosaurs?

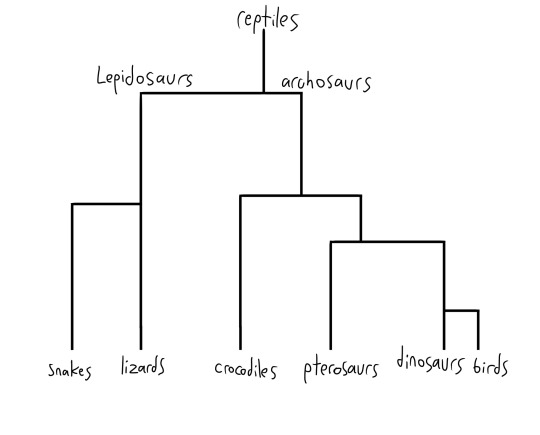

Let’s get it out of the way- pterosaurs are not flying dinosaurs. They are thought to be more closely related to dinosaurs than to any other animal, but they are not true dinosaurs. Both dinosaurs and pterosaurs belong to a group called the archosaurs, which were the group of animals that dominated the land in the mesezoic.

For those of you who are more visually inclined, here’s the incredibly oversimplified version of where pterosaurs sit on the reptile family tree:

Pterosaurs themselves can be split into two main groups, rhamphorhynchoids and pterodactyloid pterosaurs.

Art credit: Christian Klug

Rhamphorhynchoids were the earlier kind of pterosaurs, and lived from the late Triassic to early Jurassic. They were smaller, and they had features like teeth and long tails that later pterosaurs lacked. Members of this group include rhamphorhynchus, dimorphodon, and caelestiventus.

Art credit: Simon Stalenhag

Pterodactloid pterosaurs were the later kind, living from the Jurassic to the end of the Cretaceous. Their size ranged from small bird to fighter jet. They lacked long tails, and despite their portrayals in media, most lacked any form of teeth. This group was much more diverse, and in my opinion, more interesting.

Here’s something more people should know about! Pterosaurs didn’t have the leathery skin that is often portrayed in media. Like many dinosaurs, pterosaurs were fluffy. They were covered in fur-like filaments called pycnofibers. It is increasingly looking like pycnofibers are actually a form of feathers, but this is still hotly debated. Pterosaurs likely had this layer of fluff for thermoregulation- keeping warm or cool- and aerodynamics- like how birds use their body feathers.

As well as being fluffy, they were likely warm-blooded, as many studies have found that pterosaurs would not be able to keep up their lifestyle with cold blood.

Another interesting thing about pterosaurs is that they had very efficient lungs along with a system of air sacs that helped direct air throughout their body and made them lighter. Pterosaurs and dinosaurs had only one path throughout their lung system, instead of two, like mammals. This made oxygen exchange much more efficient, and oxygen exchange is very important when you’re flying like a pterosaur or huge like a dinosaur. Additionally, they had air sacs throughout their bodies that again allowed oxygen exchange to be more efficient, and also allowed them to be lighter, helping them again to fly or be huge.

I will also quickly mention that pterosaurs would not be able to stay in the air without rounded wingtips, so they probably didn’t have the sharp wingtips that you see in movies.

There’s some misconceptions cleared up and some cool information about pterosaurs as a whole. Now let’s move on to some notable species.

Art credit: cegebe

Pteranodon- the one that’s so iconic that everyone just calls pterosaurs pteranodons or pterodactyls. Pteranodon means ‘wing without teeth’, which makes it even more funny to me that people often portray it with teeth. They had an impressive wingspan at seven metres (23ft)- that’s two and a bit cars- but it wasn’t the largest wingspan sported by a pterosaur. Like the classic portrayal of pterosaurs, they were probably piscivorous, and would have skimmed the surface of the water with their beak like some modern birds. Though pteranodon is iconic, and justifiably so, it’s not exceptional among its peers.

Art credit: Mark Witton

Dimorphodon is a good representative of the rhamphorynchoid pterosaurs. As a hunter, it probably preyed upon small mammals and reptiles. It had a one-and-a-half metre (4ft) wingspan, roughly the height of a person. As it and its relatives predated birds by tens of millions of years, whereas other pterosaurs lived alongside birds, they would have had the airspace all to themselves, and would have been the only flying vertebrates flitting from tree to tree. Rhamphorynchoid pterosaurs are unfortunately not a diverse group, so dimorphodon is the only member I will include.

Art credit: Julius Csotonyi and Alexandra Lefort

Quetzalcoatlas is notable for being the largest flying animal of all time. When standing, they were 6 metres (18ft) tall, or as tall as a giraffe. When flying, they had an estimated wingspan of 10 metres (34ft), the size of a small fighter jet. They were so big that there have been some debates over whether or not they could even fly. They were probably predators or scavengers, either chasing after their prey on the ground or gliding huge distances to find the remains of giant dinosaurs. Quetzalcoatlas’ relative, hatzegopteryx, may have been the apex predator of the island it lived on. It’s so cool to think about the sheer size of the biggest flyers that ever existed.

Art credit: Adrian Gonzalez

Tapejara was a small pterosaur from Cretaceous Brazil. Unlike many other crested pterosaurs, the majority of of tapejara’s crest was not made of bone, but of a membrane of skin. One thin bone in the front of the crest supported a structure unknown in size and shape. It had the same metre-and-a-half wingspan of Dimorphodon, but unlike Dimorphodon, it had to compete with other small flyers- birds.

Art credit: Sergey Krasovskiy

Tropeognathus is known for its odd-looking jaw. Not only was it one of the only pterodactyloid pterosaur to have teeth, but it had this odd keeled-jaw that it would’ve used to catch fish. It was vaguely related to pteranodon. It’s wingspan was eight and a half metres (27ft), which several sites tell me was the largest pterosaur in the Southern Hemisphere- though take that statistic at your own risk. By the way, that wingspan is still a metre wider than the longest snake ever recorded. I think it’s easy to look at paleoart and forget how big these animals are. When standing, these flyers would’ve been the height of your average person. They may not have been quetzalcoatlas, but they were still massive.

Art credit: Julio Lacerda

Nyctosaurus is another mostly run-of-the-mill fish-eating pterosaur. It was quite small, with only a 2 metre (6ft) wingspan. What sets nyctosaurus apart is its ridiculously extravagant head crest. There’s a running joke in palaeontology circles that any structure on an animal with an unknown purpose will simply be labelled as a display structure- nyctosaurus is my favourite example of this. It seems laughable that any animal would evolve such a large, possibly inconvenient structure for no other reason to attract a mate, and yet every other explanation has been tossed out. I sometimes see this head crest restored with a membrane between the points, like tapejara’s soft tissue crest, but unlike tapejara, nyctosaurus does not seem to have grooves in the bone that would implicate a soft tissue crest.

Thank you all for coming along with me on this journey throughout the world of pterosaurs! They’re such an interesting group of animals, and I wish more people were as fascinated with them as I am. But, I suppose, let this post be an introduction to pterosaurs that sparks your imagination enough to look into them more. I hope you enjoyed being educated, and have a great night!

415 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello, and welcome to an educational post about dinosaur colouration!

From the bright green cartoon rex to the mottled browns of paleoart, the colour of dinosaurs has been heavily debated over the years. And it’s easy to see why- rock may preserve bones, and sometimes even feathers, but what rock could preserve colour itself?

Well, as it turns out, under some circumstances, and with the advancements of modern science, we can actually infer colour from fossils.

If you’re at all interested in feathered dinosaurs, you probably already know that rock can occasionally preserve not just bones, but so-called ‘soft tissues’ like feathers, skin, organs, and stomach contents. This only happens in very specific kinds of rock, though. And rarer still, in only a few kinds of rock, cells themselves can fossilise. The cells’ contents, tiny structures like nucleui and mitochondria, can leave impressions on the rock that can be seen through microscopes tens of millions of years later.

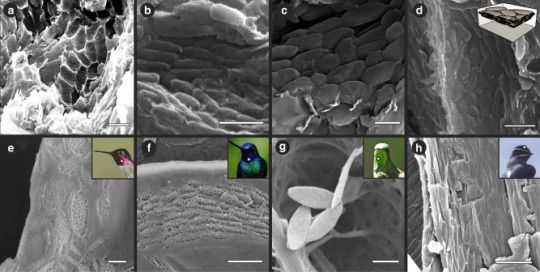

Among these cellular remnants are the structure we’re interested in today- melanosomes. Melanosomes are the tiny structures that give organisms their colour. By looking through a microscope and comparing the shape of fossilised melanosomes to those of animals living today, we can infer the colour that the ancient animal had. This is an incredibly exciting new area of palaeontology that could help us find answers to questions that were previously thought to be unanswerable.

The method has its limits, of course. Melanosomes only preserve under incredibly specific circumstances, so we will only ever find a few fossils that we can analyse like this. It is incredibly unlikely that we’ll ever know the colour of popular dinosaurs like tyrannosaurus rex or spinosaurus. But there are dinosaurs whose colours we can know.

Let’s take a look at some, shall we?

Art by Madison Henline

This is caihong juji, a little birdlike dinosaur from the Cretaceous period. Caihong juji had mostly black feathers, save for its neck and the front of its wings. Although the exact colour of this area isn’t known, the melanosomes are similar to those of various brightly-coloured birds like hummingbirds. This area would have been colourful and irredescant, hence the first part of its name, caihong, meaning rainbow.

I wanted to make the first example this dinosaur because a picture from the study concerning its colour helps illustrate the concept of melanosomes.

These are melanosomes, as seen under an electron microscope. The top four pictures are fossilised melanosomes from caihong juji, and the bottom four are melanosomes from modern birds. I’m always fascinated by things this tiny. There’s a strange beauty to them.

Art by Mick Ellison

For some odd reason, so many of the dinosaurs whose colours are known are four-winged birdlike dinosaurs. This is microraptor, one of the more popular coloured dinosaurs. It was not just black, but irredescant black. Imagine a crow or raven gleaming dark blue or purple in the sun- that is what microraptor would have looked like.

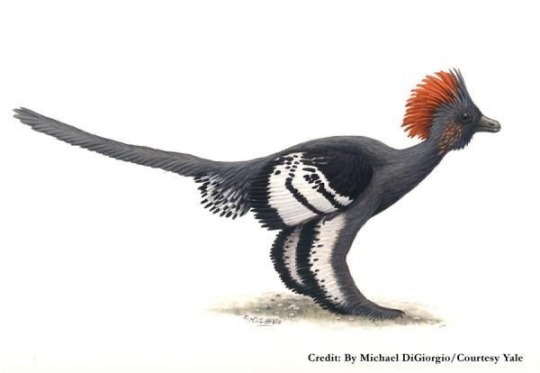

Art by- well, it’s in the image. Michael DiGiorgio.

This is anchiornis, the most wonderfully detailed coloured dinosaur. It’s colouration is so reminiscent of modern birds. Interestingly, one specimen was found with a red crest, while another wasn’t. There are a number of different explanations for this, my favourite being that, just like modern birds, they were sexually dimorphic. That’s entirely speculative, of course, don’t take that to heart.

Art by Gabriel Ugueto

This is my favourite coloured dinosaur, sinosauropteryx! It was a fluffy relative of compsognathus. I love it because its colouring is reminiscent of so many modern animals. It really helps me imagine dinosaurs as living, breathing animals that actually once existed.

Art by Robert Nicholls

And, finally, we have Psittacosaurus. It’s notable for being only one of two ornithischian dinosaurs whose colours are known. Colours weren’t the only thing preserved in its fossil, as it also turned out to have these odd bristles on its tail that may or may not be related to feathers- that’s an incredibly complex topic that I will cover another time.

Thanks to everyone who enjoyed my last post and motivated me to finally do another one. I really hope you’ll all continue enjoying my educational content in the future. Have a great afternoon, everyone!

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello everyone! Welcome to an educational post about synapsids!

I haven’t met many people who even know synapsids exist, which is a shame, because they were and still are really cool animals! So today I’ll be teaching you about them.

So what is a synapsid?

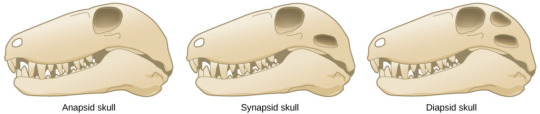

Well, in the most basic terms, whether or not an animal is considered a synapsid depends on how many holes they have in their skull.

Anapsids, an ancient group of primitive reptiles, have no holes in their skull besides their eye sockets and nostrils. Diapsids, which include birds, reptiles, dinosaurs, and pterosaurs, have two. Synapsids have only one. That is the basic definition of a synapsid. But what kind of life are they?

Many people never really think about what happened between the time when fish first invaded land and the time when dinosaurs lived. But there is actually a rich and storied natural history between those two points in time. In that time, amphibians became reptiles, and then reptiles split into two main groups- the synapsids and the diapsids. The diapsids would later evolve to become crocodilians, dinosaurs, and pterosaurs. But tens of millions of years before they did, synapsids evolved into many weird and wonderful forms that ruled the earth for over 150 million years.

Let’s take a look at some, shall we?

Art by Max Bellomio

This is dimetrodon, the most famous ancient synapsid. You might have seen it being called a dinosaur- it’s completely unrelated. Dimetrodon were the largest known member of a group of ancient synapsids that sported long neural spines (those are the spines that come out of some animals backs) that held together a membrane used for temperature regulation and possibly display. Dimetrodon is notable because it was among the biggest carnivores of its time, at a length of 3.5 metres (11 feet).

Art by Jonathon Kuo

This is another semi-famous synapsid, a group called the gorgonopsids. They were large predators, for the time- the biggest species were 3 metres (10 feet) long, and they were among the first animals to ever have sabre teeth. They were the apex predators of their day, and it’s easy to imagine why.

Art by Sergey Krasovskiy

I love how bizzare prehistoric life sometimes was, and cotylorhynchus was a great example of this. The larger species were among the biggest synapsids of the early Permian period, at 6 metres (20 feet) long. They had these hilariously bizzare proportions, with a comically tiny head against such a large body. They may have been aquatic or semi-aquatic, using their little hands to paddle, which I think is even more funny. You do you, cotylorhynchus.

Art by Dmitry Bogdanov

Lystrosaurus was a little cave dweller that used it’s beak and tusks to dig little burrows. Because it spent a lot of time underground, it was able to survive breathing in large amounts of carbon dioxide unharmed. It may have been this ability, combined with the fact it didn’t need to come to the surface very often, that helped it survive the greatest mass extinction in earth’s history- the great dying. This event drove more than 90% of the earth’s species to extinction through a combination of volcanic eruptions, global cooling, and increased amounts of carbon dioxide. Lystrosaurus didn’t just survive- in comparison to many of the other species of the time, it thrived. In some places, it accounts for most of the fossils found from this time period, and as such is very well known by palaeontologists.

Art by WillemSvdMerwe

I’ve saved my favourite for last. Meet Estemmenosuchus! Sadly there isn’t much to say about it as it isn’t super well known, but I love it just for the horns. I mean, out of all the super extra display structures I’ve seen in the animal kingdom, these are up there.

So, what happened to the synapsids? Did they go extinct, like the dinosaurs? Well, no, they’re actually still around today!

After the great dying, crocodilians, dinosaurs, and pterosaurs started to dominate the land, and the larger synapsids all went extinct. They became small, with rat-like bodies, fur, and warm blood. They stopped laying eggs, and evolved pouches, and later the uterus. After the dinosaurs went extinct, they once again survived by being burrowing creatures. They then diversified, and became everything from elephants to lynxes to humans. These animals I’ve showed you were our ancestors!

I’ll do a post on other synapsids, like prehistoric mammals, another time, but for now here’s some cool info on the ones that lived before the dinosaurs.

I hope you enjoyed being educated, and have a great night!

313 notes

·

View notes