Text

To keep up with my recent work, please visit the Japan Game Lab blog.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

First up, this is the order of activities that students complete as part of this lesson:

Check English errors

Translate JP to EN

Presentations

YouTube viewing

Set up

Before this class, students played a game and recorded the audio during the play session. For homework (or for the time remaining in the previous class) they collectively transcribed the audio and wrote down how many times each member spoke English in a tally.

Checking errors

The first activity of the class is for students to collectively look at their transcriptions for any mistakes they made in English. Of course, it is not obvious to them when they are making mistakes and I often hear the lamentation 「間違えているか分からないよー」as I walk around. However, they can easily pick up on the fact that they are mostly interacting by using single words (Open. Who? Werewolf. This. You? Next.). I walk around the class looking at students transcriptions, marking areas that I think they should explore further. Today I pointed out the following expressions as areas to look into:

I want you to…

Because / because of / so

Should / shall

He said / who said…?

There is / there is no…

There’s a good chance…

“a” and “the”

The students also realised that they used a lot of Japanese unnecessarily. Things like ‘そうだね’ or ‘これとこれ’ really shouldn’t be being said in Japanese. It’s not like they don’t know how to say such simple things in English, they just didn’t realise that they were using Japanese until they listened back to the audio and made the transcriptions. Taking the game ‘Insider’ in particular, the group noticed that the main part of the game occurs after thekeyword has been guessed correctly. They also realised that this was the stage where they pretty much only used Japanese. However, I told them that it was not a problem. Certainly not a negative. The fact that they transcribed all of their Japanese discussion for use in today’s class is great. Why? Because it gives them the opportunity to think about how they could do the same discussion in English. I also told them that some students don't transcribe the Japanese parts they spoke because they think it’s ‘against the rules’ to speak Japanese or that it is not important for the post-play analysis. Realising that the L1 can be a launchpad to thinking about the L2 is a great step here. That is the purpose of this lesson: to critically evaluate their previous performance and to collectively try and improve their knowledge for the next play session.

Presentations

Each class does the same third stage, which is to present any interesting things they found during the first and second stages. Using the whiteboards that they have available to them, they write out a few English grammar points and Japanese to English translations. But why present their findings? I think there are two positive outcomes of presenting.

They reinforce their knowledge of items,

They provide other groups with useful expressions that may not have come up in their own discussions.

I want to write a few thoughts regarding 2) above by referencing what happened in today’s class. One group (the Resistance: Avalon group) introduced the expression ‘I want you to ….’ I then asked other groups in the class how they could use the same structure in their own games. The Captain Sonar group realised very quickly that the engineer could use this structure. Another group introduced ‘Shall we….’ and ‘You should’ which was picked up by the Avalon group as something they could use when deciding who should be picked to go on a quest. This continued until all groups had introduced some useful expression, phrase, or word that could be used in their games. The point here is that although the games are different, there is great learning potential in getting students to share their findings because other groups may benefit from incorporating the expressions into their own context. It’s impossible for me to give precise grammar instruction to all groups (or at least, it would take [number of groups] x 90 minutes), so for them to instruct each other is a great compromise, and the laidback, community-based environment is one that I think the students enjoy. It is a real pleasure to see.

Issues:

A criticism of this activity is that students are generally only looking up one-to-one translations for expressions meaning that instead of introducing structures (as shown above) they will introduce extremely specific sentences translated from Japanese, or just one to one lexical items such as ‘当たった is Hit! in English.’ My next goal is to get them looking more deeply at the grammar behind what they want to say.

YouTube viewing session

This is possibly the most difficult part of the class for the students and as a result, very difficult for me to provide guidance. Here’s why:

Issues

YouTube auto-translations are incredibly unreliable.

Videos sometimes don’t exist (like for Insider)

Videos with subtitles are rare.

Native speakers talk too fast and interrupt each other a lot which means that the listening activity is too advanced for the students

Students don’t take time to pause and reflect on what they are hearing.

However, it is not all doom and gloom(haven). Although there are not many games that feature subtitles on YouTube, some generous, kind and wonderful people do include subtitles. Subtitles can be accessed by pressing “filter” on search results:

I also had a really interesting experience last week doing this class. One group played Mafia de Cuba, and so watched a YouTube video of native speakers playing the game. This video: [su_youtube url="https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GgOr73d0fHI"] What was so amazing was that having played the game themselves the previous week, watching the video was a real pleasure for the students. They got to see other people's tactics, see how the game unfolded, and were enthralled in watching. We spoke about it afterwards and came to the conclusion that because they were deeply interested in the content, and wanted to know how the game would conclude, it didn’t feel like traditional “English class video-watching.” The group were instructed to rewatch the video more critically after the first viewing to understand what was being said, and look for expressions that they could use in their own gameplay. Therefore, students do pick up expressions from the videos, write them down, and finally share what they found with their group, further increasing their potential repertoire for the next class. However, this whole section needs more work.

Final ideas

Possible ways to improve the class:

Provide common grammar error handouts to complete for homework

Such handouts could be created by myself, or the students could be pointed to specific websites to study grammar. The only issue I see here is that, unless they are really motivated to learn the grammar, I can’t see a lot of students being excited to do this activity.

Dedicate time to explain how to look for grammar guides online.

As mentioned, Students just look at Google Translate for one-to-one translations, not websites that explain the details behind the how and why of English grammar. I think it would be beneficial for students to learn how to use digital tools to help them acquire correct grammar rules during class time. I also think they should be expected to explain grammar rules to other groups as part of the their presentations.

Possible extensions to the class:

Quiz each other at the start of the following class before replaying the game.

I could make a short test based on their findings and make a more structured quiz also.

As always, thanks for reading. Comments welcome.

#kotoba rollers#kotobarollers#efl#tdu#game-based learning#game-based language learning#GBL#GBLL#higher education#active learning#collaborative learning

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kotoba Rollers Post-Play overview

Noticing, grammar, skill disparity, and making connections

I'd like to reflect on the post-play activities that I've been doing in class recently. There is a lot to unpack, but I think it is important to get this down in writing. In this post I will be giving an overview of what “post-play” currently looks like with the Kotoba Rollers framework, providing rationales for why I've taken this route and informal observations of it in action.

Post-play activities overview

Record the audio of the game session

Each member transcribes a specific section of that audio for homework (decided by themselves) The following class:

As a group, go through the transcription and correct English mistakes (as best as they can) and translate any Japanese into English (again, as best as they can)

Complete a grammar exercise to target common errors (as chosen by me)

Relate the grammar exercise to the game in order to see how the grammar could be used as part of gameplay (coming up again the following week).

So let's dig into this in more detail.

Self-transcription as a way of noticing

I'm not the first person to look at this topic, and in fact I was introduced to the concept of self-transcription by blog member @jonathan (see deHaan, Johnson, Yoshimura & Kondo, 2012; Mennim, 2012 for examples). But why self-transcription all of a sudden? Well...

When playing a game, we are often so wrapped up in the experience that we may forget what we said, what was said by others, and if that player opposite us purposely chose a Minion of Mordred to go on Quest 3, failing the quest and ultimately dooming the game for the Loyal Servants of Arthur (see Resistance: Avalon). This is what is known as flow as introduced by Hungarian psychologist Csikszentmihalyi (1990). Or, as Queen sang about 'having a good time.'

We've probably experienced this state even as native speaker, which is why the literature on simulations and gaming has called for a debriefing session after play in order for learning to actually occur. In other words, it's theorized that reflection on what occurred is where real learning takes place. Which makes sense right? Being caught up in the moment to moment of game play does not allow us much head room (or more scientifically: cognitive capacity) to think about what is occurring on a level such as 'Did I just use the wrong verb here? Should I have said 取る instead of もらう?' No, we just want be as fluent as possible, get our message across and communicate effectively. Thus, during play we do not have the ability to truly notice our mistakes (as used in an SLA/TBLT sense of the word).

Anyway, I'm detailing this post a little with the above. Back on track:

In summary, students need a post-play stage to reflect on what occurred during the game to notice where communication broke down, where they spoke Japanese (thus noticing what English skills they are missing). As part of this, and from a TBLT approach, a post-play activity that forces students to focus on accurate language use is considered beneficial. This is why I am currently experimenting with post-play self-transcription and grammar focused activities.

Self-transcription Activity 1

Practically, students are told to complete their transcription on a Google Spreadsheet that I set up for them before class. Here is an example (names obfuscated). Then, during the next class students spend approximately 45 minutes looking at the document, working in pairs or as a group to:

correct English mistakes

translate Japanese utterances into English

Upon completing this section, their 'reflection' still isn't finished. Not by a long shot. The goal of the class is not only to reflect on their previous play session, but to prepare them to play the game again, hopefully with more tools to get the job done (i.e. an improved interlanguage and more words, phrases, grammatical knowledge, and hopefully more communicative competency).

Self-transcription Activity 2: common errors

As per the title, the next phase is to scrutinize their English errors and Japanese usage to find the most common culprits. For example, they may notice that they never use the word 'will' to signpost an action they are going to do (as is very common from my experiences), they will write this down on their post-play worksheet.

GRAMMAR: [person] will [action]

USAGE: I will move here.

The same goes for common Japanese expressions that they used:

JAPANESE: 〜ても良い?

GRAMMAR: Can I...

USAGE: Can I take this token?

My thinking behind this activity is: after going through their transcription, correcting errors and translating Japanese utterances, a distillation of common errors should help cut out further occurrences in future playthroughs, and considerably reduce errors. Consider the 80/20 principal. With this way of thinking we can assume that roughly 80% of errors come from 20% of causes. In other words, there is probably a commonality between a large portion of the errors made, relating to only a few grammar issues (for instance: the lack of articles could up 50% of the errors).

Grammar instruction

Students need explicit grammar instruction (or so I thought, more on this soon). The literature on TBLT and SLA in general posits that implicit (unconscious) an explicit (conscious) grammar learning is essential in developing language skills (see Long, 2014 for a discussion on implicit vs explicit learning).

Here is how I am approaching it with Kotoba Rollers.

I’m a big fan of the book “Essential Grammar in Use.” It has clear explanations and activities to practice using the target grammar. As such, I have created some worksheets which emulate the format. I bring a number of different worksheets to class based on their observed needs and students choose which of them they want to complete. They work in pairs, and groups make sure that collectively they do all of the different worksheets (i.e. Group 1 Pair 1 do Worksheet 1, Group 1 Pair 2 do Worksheet 2, etc.).

Fairly straightforward, right? Choose a relevant grammar activity and complete it in pairs. Fine. But this is where I want to stop just a moment and talk about my observations.

--- [Aside] --- I’m not familiar with the way they are taught grammar in their “reading and writing” class (which is taught by a native Japanese teacher), but I’m fairly certain that they have no choice regarding what grammar they study, deem important for their needs, or its applicability to an upcoming lesson that is scheduled. However, I digress...

The worksheet, similar to the Essential Grammar in Use book, has the grammar explanation on one side, and some questions to test their knowledge on the other. I expected students to read through the explanation, acquiring new knowledge about the construct, and then attempt the questions. My assumption here is based on the fact that they are not using such grammar constructs in their utterances during gameplay, and thus the need to provide this new knowledge. However, what actually happened on the whole can described in this conversation between me and a male student (in English and Japanese):

Me: OK, so read about the grammar point and answer the questions on the back of the worksheet.

Student: Leave it to me! I don’t need to look at the explanation!

Me: Are you sure?

Student: No problem!

To which he set off doing the exercises with his partner. They probably only made reference to the grammar explanation once during the whole 20 minute period that they worked on the questions. Thus, there is a huge disparity in my students grammatical knowledge, reading and writing skills, and speaking skill. In other words, their knowledge of English far outweighs their functional ability or communicative competence in English. I had assumed that they didn’t know how to form If__, then __ will__ (first conditional) sentences, but they completed the exercise questions without too much of a problem. Observing such helped me realize where the focus of my class should be: on bringing that knowledge to the forefront and turning it into communicative competency.

Of course, this student may be more proficient than some of his peers. Other students may learn a lot from the grammar worksheets. Or, at least, refresh their memories regarding usage. Thus, I still think this stage is beneficial for interlanguage development.

So, let’s bring this full circle:

Connecting grammar exercises to gameplay

Upon finishing the grammar worksheet, I asked students to take 5 or 10 minutes to brainstorm how they could possibly use the grammar point during their upcoming play session. For example, the grammar X should Y or I don’t think X should Y could be used very effectively in The Resistance: Avalon:

I don’t think you should choose X for this quest!

They write their brainstorming ideas down on their post-play worksheet, which can then be referenced during the next play session.

I’m very happy with the way the framework is shaping up now, and I hope to collect some useful data to show the effectiveness of self-transcription.

In summary then, my current methodology is comprised of the following:

get students to self-transcribe,

notice their English mistakes and Japanese usage,

find common errors,

complete a worksheet of their choosing to help them understand that grammar point in more detail,

apply their acquired knowledge from the grammar worksheet to the following play session.

As always, thanks for reading this far. Comments are welcome. I leave you with a picture of Dead of Winter: The Long Night, which I played last week and highly recommend (in fact, don’t by the base game, because this is all you really need)!

References

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

deHaan, J., Johnson, N. H., Yoshimura, N., & Kondo, T. (2012). Wiki and digital video use in strategic interaction-based experiential EFL learning. CALICO Journal, 29(2), 249-268.

Long, M. (2014). Second language acquisition and task-based language teaching. John Wiley & Sons.

Mennim, P. (2012). Learner negotiation of L2 form in transcription exercises. ELT Journal, 66(1), 52–61.

#board game syllabus#Kotoba Rollers#kotobarollers#EFL#TDU#game-based learning#GBL#game-based language learning#GBLL#SLA#TBLT#task-based language learning#board games#Japan

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The hype is real

Today was a very interesting day, and I’ll get to the reason for that later. For a start though, let me say that I am exhausted.

Why?

Two reasons:

I had to carry a bunch of games to class today:

Scythe (Collector’s Edition no less..!)

- Sheriff of Nottingham - 2 x Pandemic - Forbidden Island - Dead of Winter 2. I had to walk around all of these groups and help them learn the rules to these games, answer questions, and generally make sure all students were on task.

The KR framework puts students in control. They are in charge of choosing a game, learning the rules, and progressing the play session. But… I’m still the expert regarding game rules and English, so I’m still very much needed to oversee the proceedings during class. Still, its a good kind of busy. I’m not policing kids into using English or staying on task, I’m helping them understand difficult concepts and getting them ready for game play, so I’m happy in my current role.

The “New Student”

(For me at least)

As you probably know by now, my context can be difficult sometimes. I work in a science and tech university with students that are generally not interested in learning English, so sometimes it is hard to get them motivated.

However, today I walked into class to be greeted by a new face. I thought he might be re-sitting the class (as in, he failed the class last year, and was thus retaking my class this time).

Anyway, I left him alone and started the class as normal.

He joined the Dead of Winter group and proceeded in taking control of the rulebook, reading very proficiently, and generally taking control of the group’s progression.

He doesn't sound like a student that would need to retake an English class… is what I started to think.

When his group had a question regarding the rules, he would ask in English:

“What does this mean?” “What do I do when a character is bitten?” etc.

Great!

Come the end of the class:

York: Are you retaking this class?

Student: No.

(This is a first year “RT” class)

York: Are you a first year RT student?

Student: Yes.

(OK, I’m finally figuring this out: If he is also a first year RT student, this implies that he is registered with another teacher and sneakily coming to my class, possibly because he has heard that we will be playing games… Not cool)

York: OK, so which teacher are you registered with?

Student: I’m not… I have EIKEN level 2.

York: So you don’t need to take English.

Student: I know, but I want to join this class..!

Amazing!

Let me explain:

English classes are compulsory at my university for all students, unless they have a high TOEIC score or EIKEN level 2 and above. So essentially, this student doesn’t need to take English. He has a bye. Yet here he is going out of his way to attend my class, a class that he won’t even get credit for.

This is fine by me. He was a great influence on his group, tried hard to keep the discussions in English, completed the assigned worksheet tasks, and was obviously keen (almost hungry) to learn the game rules with his peers.

A good day indeed.

#board game syllabus#kotoba rollers#kotobarollers#DGBLL#DGBL#GBL#game based learning#board games#EFL#TDU#SLA

1 note

·

View note

Photo

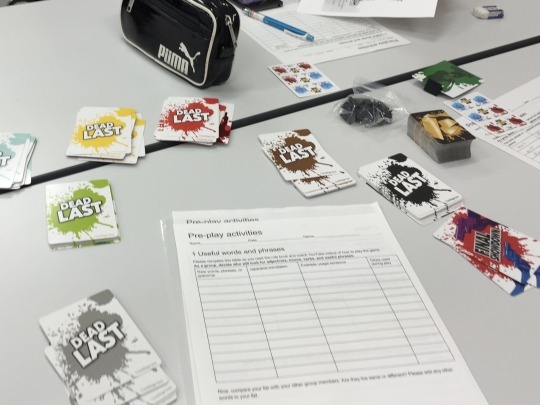

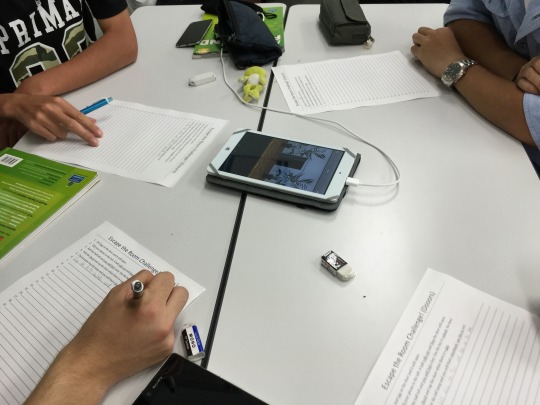

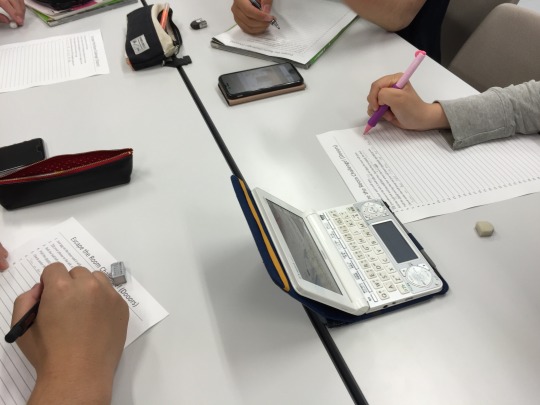

My normal teaching context is classes of 20 to 25 students, so they are split up into different groups based on the game they chose to play the week before. However, today I had the opportunity to use the KR framework in a class of only five students. It was a big change, and in today’s post, I’d like to talk about some of the things that I noticed that are different between this one-off class and my normal teaching context, as well as my reflections as a participant. I’ll be touching on the following topics:

Researcher as participant

Students staying on task

Individualized instruction

The ZPD and NS-NNS interactions

The actual lesson that we did was the pre-play, rule-learning class. Students didn’t choose the game that we played, I selected it before the class. The game is called “Dead Last” and you can find reviews of it here. I'll quote the SUSD site for their description of how it plays so you can get the gist of the type of interaction that is involved.

Dead Last […] begins with 6-12 players sat around a table, each with a coloured standee, a private deck of cards and an unusually shifty look. As soon as the game begins people will start murdering each other by consensus and/or killing themselves by accident, and your objective is to be one of the last 2 people left standing.

Essentially:

You vote for someone to be murdered and all play a card facedown

The person (or 2 people in a tie) with the most votes is eliminated

If you didn't vote for the person that was murdered, you are also eliminated

If you suspect you'll be the target, you may play an AMBUSH card and if it turns out that you ARE the target, you can eliminate one of those that voted for you.

The game rules are not the main focus of this post, so if you are curious as to the rest of the rules, please check the above links.

So what did I learn today? Read on:

I personally need to experience the framework

I have to admit it. As a researcher, I read papers, have a firm grasp on mainstream SLA theory (mostly), think deeply about how to engage students in their learning, and make appropriate worksheets. But, I don’t actually trial these worksheets on myself.

Today I had the opportunity to participate as a student and experience the pre-play worksheet firsthand. It was a very valuable experience. There are three sections on the worksheet.

The first section ask students to scan the rulebook and look for interesting and useful words that they think they will need during gameplay.

The second section asks students to write down one important rule for the game they're about to play.

The third section is about tactics and it requires the students to write what they think they will do during the game.

Regarding the first section, the problem is that there is a difference between the vocabulary in the rulebook and the phrases and vocabulary that they will use during the game. So I saw students writing down new words that they did not know, but the majority of these words were only useful in explaining and understanding the rules and theme of the game. So after the students completed the first section, we actually had a brainstorming session to think about the types of words we will use during the game. My original plan was that this would be done by scanning the rulebook. Instead it actually took a second, slightly more focused activity. I know Jonathan has done work with one of his undergraduates which examines the difference in rulebook and gameplay discourses, so I guess I shouldn’t be surprised that the two do not match up.

The second section regarding important rules for the game I thought was a sound section that did not require too much editing. It was interesting for me to see that the students had different ideas for what they thought was an important rule. So getting students to share these ideas is possibly beneficial in making all students aware of the important rules of the game.

The third section was also quite interesting in that it requires students to write about their tactics. But Dead Last is a competitive game, so in actual fact we decided that it was best to keep the tactics talk until after the game had finished.

In summary then, I found the experience of actually taking part in the class really helped me refine the worksheet.

Students staying on task

The biggest difference that I noticed between this small class and the larger class is just how on-task they were. In the larger classes there are usually four to five different groups, and so it is impossible for me to sit down with them all and guide them through the worksheet. They have to figure out exactly what I want them to do, and they are also in charge of completing it. However in today's class with only five students, because of my presence maybe, students took time to do the activities on the worksheet one by one. What I noticed in larger classes was that students were not reading and analysing the words in the rulebook, but merely translating it into Japanese (so that they could understand it, of course).

Individualized instruction

During our brainstorming session for words and phrases that we thought would be useful for gameplay, we had the opportunity to talk about the word “betray.” One student asked me how to say 裏切り者 in English, which led to me talking about “betray,” “to be betrayed,” and the word “traitor.” This “just in time” feedback and discussion is something that I cannot achieve in larger classes. Although I'm not 100% sure of Jonathan’s and Peter’s teaching situation, I felt like having a small group of students like this was perhaps similar to some of their own projects (and made me a little jealous, haha).

It felt great to be able to help students on such a personal, almost one-to-one level as they needed it.

Social interactions in the ZPD

It goes without saying really, but today was a fantastic chance to experience learners working in the ZPD. Having me, an expert speaker of the TL, as part of the group helped them hear how natives would approach certain constructs during the game, and they were able to modify their own output based on what they heard. Additionally, from a psycholinguistic perspective, I saw the value of recasts as a way for learners to notice any issues with their output. Recasts however, do not require a native speaker or expert as such, their peers should be able to provide such feedback, too.

For an example of our interactions, I showed a certain card to one of the students and said:

York: I will definitely vote for this player.

Student: Definitely? (repeating the word to show that he did not understand the meaning)

York: Yes, definitely. (reformulating the sentence:) I will 100% vote for this player.

Student: Oh, I see.

York: Will you vote for this player?

Student: Yes.

York: Definitely?

Student: Definitely!

This leads me to the more essential point that this game provided the opportunity for such rich interaction, and a stronger sense of the value of my research in this field.

I only made informal observations today, but they helped me think more critically about the worksheets I am developing. Additionally, participating in gameplay confirmed what I have been reading in the literature on game-based language learning, and my own assumptions regarding the power of the Kotoda Rollers methodology. That is: with the right amount of support (activities and teacher instruction), games can be used effectively as part of a TBLT approach to language learning, and I’m positive about my work and research direction.

In the next class, we will go over the recording of today’s gameplay session and focus on their English mistakes and unnecessary Japanese usage. Thus, hopefully raising their understanding of the gaps in their interlanguage, and preparing them to replay the game at a future date.

As always, thanks for reading.

#board game syllabus#kotoba rollers#kotobarollers#DGBLL#DGBL#GBL#game based learning#game based language learning#EFL#SLA#TDU

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Learning rules & Takoyaki parties

I was trying hard to come up with a metaphor as to why it is important to learn game rules in English before playing a board game. On other words, not taking the easy route and learning the rules in Japanese first, but actually taking the time to sit down with the English rulebook and go through it with their groupmates.

Of course there are a bunch of good reasons why they should do this. It's L2 input for a start..! It's a reading task which is activating their passive skills, allowing them to recognise and perhaps recall vocabulary without time constraints. From a sociocultural perspective, it allows them to discuss the meaning of phrases and words as a group, and perhaps notice the meaning of certain words just from context. But I wanted to give them something easy to understand without going all meta-linguistic, so here is what I came up with:

The ever-so-not-quite Takoyaki party

(A takoyaki is a fried dough ball with octopus (tako) and pickled ginger in. It is often garnished with mayonnaise and sauce as well as many other things. See the picture above)

[I said:]

Imagine that you and your friends are having a takoyaki party. Now what do you need to have a takoyaki party? Flower, eggs, water, tako, pickled ginger, seaweed… etc. etc.

So, what if you all arrive at the party and Friend 1 has brought sliced bread, Friend 2 has brought a lettuce, Friend 3 has brought some cheese, and you’ve brought some tomatoes… Is this going to be a takoyaki party?

No.

It is going to be a party, but not a takoyaki party. Maybe a sandwich party. Or at a push, a pizza party..? But definitely not a takoyaki party.

[I digressed:]

So where does this fit into what we are doing in this class? Well, to play these games in English, you need the tako, flour, water, and egg, too. These are the nouns, verbs, adjectives, grammar, etc. that you will find in the rulebook.

Now, imagine if you just learnt the rules to the game at home in Japanese… You could come to class and play the game, but it definitely won’t be a game in English. It will be a game in Japanese. Which is like the difference between a sandwich party and a takoyaki party.

[I ended, rather triumphantly:]

That is why you need to learn the rules in English: So you can play the game in English. The goal of this class.

So, what do you think? Was this just bonkers, or did I make a strong(?) and valid point here?

Thanks for reading as always.

#board game syllabus#kotobarollers#boardgames#efl#dgbl#game-based learning#TDU#japan#kotoba rollers#takoyaki

0 notes

Text

Rule Setting

This blog post is a reflection on the feedback I received from the initial implementation of the #kotobarollers framework (1.0 we are calling it) back in the second term of 2015. As part of that implementation, I collected quantitative and qualitative data from students in the form of a course-end questionnaire. The questionnaire was designed to see which activities students completed, which the did not, the elements of the framework they liked and those that they thought could use improvement. It is these last two questions, that were given as open-ended questions where I feel the most interesting and useful data was collected.

Firstly, let’s look at some of the comments I received.

Good points of the framework

Practical English usage

A lot of the comments I received regarding the positive aspects of the framework relate to how playing games was students’ first real experience of using English as a means of communication, and not just as a subject. The term practical came up a lot:

本当の意味での「実践的な英会話」を行う事ができた点。

I got a real sense of “practical English communication” in this class.

This is a fantastic result of the framework for me. I want students to use English, not just study it.

From a TBLT perspective, the non-linguistic goals of gameplay were the catalyst to get students talking, and using vocabulary and grammar to solve a real life activity: winning (or at least participating) the game. Compare that to a class that is fronted by the teacher saying, “Today we are going to do the activities on page 34.” Or, “Today we will talk about how to give directions in English.” Students’ expectation would vary greatly I think.

Moving on:

Willingness to communicate

The fun, and laid-back nature (for some) of the games (of course, there are high-stakes games like Werewolf or Spyfall where tensions are high) really helped learners become more willing to communicate with their peers.

英語のスピーチやプレゼンなどは緊張するが、ゲームだと気軽に話せる。

I get nervous when doing a speech or presentation in English, but with games, I could speak more freely

Again, an excellent point, but I don’t want to dwell too much on these positive points. I hoped that I would see these kinds of results before starting.

Negative points of the framework

Excessive Japanese usage

Yes, I’m sure you could see this one coming. By far and away, the biggest criticism of both the framework and the students’ own performances was that they talked a lot of Japanese during play. And this is what I want to address with the rule-setting lesson. Comments:

Blaming others:

ゲームの中で英語で話そうと生徒が努力していない時があった

Some students didn’t make effort to speak English during gameplay

Blaming themselves:

どうしても途中で英語での話し方がわからなくなり、日本語で言ってしまうのは、仕方ないと思うのですが、そのあとにだんだん日本語で話すのが増えてきてしまうのは良くないと思います。

It’s only natural that we’d use Japanese occasionally during gameplay, but once we did, then we’d end up using more and more Japanese, which I don’t think is good.

So what do they think would be a good way to reduce Japanese usage?

ボードゲームをする上で日本語で話したことによるペナルティをゲームに慣れてきたら設けるべきだと思った

When playing, if we speak Japanese, I think there should be some kind of penalty given to that student.

OK. Great. We are on the right track here. Students realise that they are not meeting me halfway by speaking Japanese, so let’s put it to them to fix it.

Rule setting lesson

So that’s where this blog post comes in. I want to put down on paper my thoughts regarding class rule-setting, what I’ve done to towards achieving this, and a reflection on my first class of doing this.

I’ve had some negative experiences with gamification, and both Jonathan and I are ardent fans of the work of Kohn: Punished by Rewards. So I really didn’t want to go full metal jacket on setting rules. That’s partly why I didn’t set any explicit rules regarding the use of the L2 in the first place: I left it for students to figure out. But the result of that has been that students just talk Japanese the whole class. Granted, some of them feel guilty about it, leading to them writing on the final report that they feel something should be done about it.

Rules setting is a tricky beast though. If punishments and rewards are too heavily utilised, we run the risk of “gamifying” the classroom and creating a negative environment. The addition of points and badges, or more generally “rewards” are sources of extrinsic motivation (from Deci and Ryan’s Self-Determination Theory), which can sometimes become the only reason students attempt to do an activity.

The often quoted example is a student that might go to the library every day in the summer to read out of sheer pleasure, then one day, he receives a point or sticker for visiting the library. After the summer is over the stickers stop coming, and so does he. He got so used to getting the stickers that receiving them became the sole reason for reading.

In other words, I don’t want to reward or punish students too severely in fear that it just makes them resent the class or lose focus on the goal of the class.

On another note about the idea of play, Nicholson (2015) writes:

A key concept from play that is important when thinking about gamification is that play must be optional (Callois, 2001). If something is not optional, then it is not, by definition, play. If a worker is forced to engage with a game, it is no longer a play experience.

This is also very pertinent to my own situation where my whole class is built around getting students to play games. I am kind of forcing students to play games right? Well, not really. Reading a few paragraph7s below on Nicholson’s paper we get:

One way to soften a required engagement with a gamification system is to ensure that the system allows for exploration. This falls in line with the concept of Choice.

Yes. My students have a LOT of choice in class.

What game to play

Who with

The post-play activities they complete.

Anyway, moving on:

I attended a conference in Okinawa in February where I was introduced to the work of Tim Murphey et al. (2014) who talked about the concept of getting students motivated by thinking about ideal classmates. There work is laid out in more academic terms in this paper.

Essentially: First, get students to think about what they would look for in an ideal classmate. Then, the following week, compile all the students answers and give them back. Students are then in a position to see what others are expecting of them. Finally, a few weeks after this, move the shift of questioning onto the students themselves, giving them chance to reflect on if they have been behaving as an ideal student based on the feedback they got from the first week.

I was impressed.

So I started thinking about how I can use this in my own class.

What is the goal?

I think the first step that wasn’t mentioned in the Murphey paper is getting the students to consider what the actual goal of the class is. This can be from their perspective, my perspective or the university’s perspective.

I want them to become more fluent in English, and particularly their speaking skills. The university wants them to gain discreet English skills week after week as they are presented………. yeah…. I can see that working…. Their goals (as they wrote on the board today ranged from: “enjoy English,” and “become an active communicator in English,” but I think a good proportion of them would probably have written “get a passing credit” as the main goal.

The idea is that based on these goals that we have identified, we need to figure out how we can best help each other achieve them. Here is a copy pasta of the worksheet I concocted:

What is the goal of this class?

What problems prevent us from achieving that goal?

What kind of behaviour will help us achieve the goal? Think of some examples:

Good

Bad

Can you think of a good rule for Japanese use (for students, and me, Mr. York)?

How can Mr. York help you speak English?

How can you help other students speak English?

Fairly to the point questions in my opinion. The only question that directly asks about rule setting is the one about Japanese usage, because I want to hear what they think, their opinions and possible solutions to the problem of excessive Japanese usage in class.

What rules can help them stay on task?

Upon completing the survey, they had 10 minutes to discuss with their group what they had written. I expected a lively conversation, but to be honest, a lot of them looked bored. There are pockets of active, interested students, but unfortunately as this is a non-English major class, there are a lot of uninterested students. There isn’t much I can do about that (or haven’t found a way so far). Here is an overview of their responses.

Their ideas regarding what can be done were quite uninspired, too. The main idea was to ban Japanese usage, which to me just seems impractical. They need Japanese for some parts of the class and its not to be demonised. That’s not the idea I want to have proliferate in my classes.

I think the idea that some students came up with a few months ago is the best way to go: by having them check themselves during gameplay with the addition of a new rule:

If I speak Japanese [something bad happens].

Well, I’m not done with this yet. I think this kind of consciousness raising is important, and I want students to work with me to decide what is good or bad behaviour, and get them to help each other stay on task.

Next week I will be handing back a list of good and bad behaviours that they wrote, and ideas for how other students can help them achieve the class goal. let’s see if it inspires them to become more aware of themselves as active learners with responsibility towards learning English themselves, rather than being taught by me at the front of the class. Because we all know how the assimilation of knowledge is as simple as me passing it from my head and into yours….

As always, thanks for reading my rambles.

References

Callois, R. (2001). Man, Play and Games. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Murphey, T., Falout, J., Fukuda, T., & Fukada, Y. (2014). Socio-dynamic motivating through idealizing classmates. System, 45(1), 242–253. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2014.06.004

Nicholson, S. (2015). A recipe for meaningful gamification. In Gamification in Education and Business (pp. 1–20). http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-10208-51

0 notes

Photo

Diceplomacy

In today’s class I wanted to try and play Diceplomacy as a way to test the KR2.0 Framework. The new framework is ㊙︎TOP SECRET㊙︎ right now, but I’ll outline some of the main points here.

First, what is Diceplomacy?

Very simply, it is a massively reduced version of the famous Diplomacy game that can take up to 12 hours to complete and features more feuds and fall outs than a low-budget soap opera. Read more on Diplomacy here. Diceplomacy on the other hand has a set of rules that fit on two-sides of A4, and the only requirements needed are a dice per player. Simple!

Diceplomacy rules

I won’t go into the rules here, as you can check them at the link provided above. However, a quick overview is:

Each player rolls one die, to determine their Power, and keep their die hidden.

On your turn, you can do 1 of the following 4 things: Declare war on another player, propose an alliance with another player, cancel all alliances, or reroll your Power die

If you declare war on another player - the one of you with highest Power scores a Victory, and the other a Defeat.

The goal of the game is to get 3 Victories.

If a player is defeated 3 times, he is out of the game.

Lesson Plan

Ok, so how am I using this game in my class? Let’s look at the structure of the lesson. Following on from this overview are notes on why I am doing each stage, what I expect, and what happened (in quoted speech).

Introduce the rules

Brainstorm useful language

Play & record audio

Transcribe the audio

Correct any English mistakes

Translate any Japanese

Play again with additional rules

Write a report on their experiences

Introduce the game

I have created a Google Slides presentation to introduce the rules.

I also drew simple diagrams on the board to highlight key points such as the rules and options available when making alliances and declaring war on other players. I plan on making slides in the future to more accurately show how these concepts work.

Brainstorm useful language

In groups, students think about what words and expressions they may need to use during the game. I collate their ideas and write them on the board.

Examples included:

Will you make an alliance with me?

I declare war on you.

Help me!

I was surprised that they couldn’t come up with much more than very basic expressions. It was like they couldn’t think about what the game would involve and were stuck at this stage, so I called the brainstorming session to a halt and decided to just play and see what happened instead.

As expected, the language they come up with will mostly be related to procedural actions in the game, not the meta-game talk such as:

If you make alliance with me, you'll be strong.

If you attack me, you'll lose.

Who’s turn is it?

Who is your ally?

Play

Play the game and record what they say.

During the play session I noticed that students really didn’t understand that the meta-game language as described above was done predominantly in Japanese, like that part of communication is not considered part of the game..! They are in for a shock when they have to transcribe ALL that they said.

Listen and transcribe

It needn't be so long, as I'm sure there will be a ton of useful language to analyse. Perhaps go through the audio until each person has had a turn in the game. That should generate enough to look at.

We didn’t get to do this in today’s class, so I have given it as homework for them to complete before next week’s class.

Upon completion of the transcription phase I want them to do two things:

Correct mistakes in English

As a group, correct any mistakes they think they have made in English and write down any common errors.

Translate any Japanese they spoke into English

This may be harder, and if necessary I can do a session on useful English for this part. I presume they will need to look at the use of - conditionals, - phrases for giving suggestions, - because / so / because of constructs.

Play again

Whether we'll have time this week or not, I'm unsure, but the next activity will be to replay the game (recording again of course).

We didn��t have time. At all. It took a surprisingly long amount of time to explain the game rules...

Upon completion of the second play through, we'll transcribe their speech again and compare it with the first session to see if there is an improvement.

For the second play through I will also add a rule:

If I speak Japanese, I have to reduce my power level by 1.

That should keep them on their toes, and, more importantly, make them aware of when they are speaking Japanese because I’m _very_sure that they speak Japanese without even thinking about it during gameplay. Conscious raising via game rules!

#board game syllabus#kotoba rollers#kotobarollers#diceplomacy#EFL#TDU#Japan#game based learning#board game#diplomacy

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dooors

We played the free iOS and Android #escapetheroom game called Dooors in class today. The activity works really well, so I’d like to share the set up.

Essentially the way it works is as follows:

Provide students with a walkthrough for the first five levels. This is used as an introduction to the type of language they will be using.

They have to do the following steps:

Complete the level

talk about how they did it as a group and write the solution on their worksheets

one of the group members comes to me and shows me their walkthrough.

If it does not require any corrections they are free to continue the game from the next level. However, if there are any grammatical or vocabulary-related (spelling) mistakes, they have to correct those and reshow me their walkthrough before they go onto the next level.

Finally, I showed them a website that had a walkthrough in English and we compared their own walkthroughs with the natives to look for similarities and differences.

The groups worked well together and were genuinely keen to get on with the clearing of levels.

I sometimes have to police groups as they don’t work together to make the walkthroughs and leave the solving to a few members and the writing to other members. However, today’s class didn’t need any harsh tactics to be used against them.

I recommend this class for teaching instructional language, prepositions and for encouraging group work among students.

1 note

·

View note

Text

JALTCALL Report

Last weekend Jonathan and I presented at JALTCALL, a conference held at Tamagawa University in Tokyo (well, closer to Yokohama, but still within the Tokyo prefecture). Here is the abstract to our presentation:

The popularity of board games has risen steadily over the last decade reaching annual sales in excess of $800 million in 2014 (ICV2, 2015). Board game funding figures have also overtaken those of video games on the popular crowdsourcing website: Kickstarter. Yet, despite their increasing popularity, there is little research on the use of board games as a teaching tool in educational, let alone language-learning contexts. There is a greater tendency for researchers to be concerned with the use of digital games such as MMOs and other online virtual spaces. MMOs offer a great opportunity for intermediate or advanced learners to communicate with native speakers of the target language, but for low-level learners (such as those found in Japanese high-schools or non-major university courses) such domains may be too cognitively complex, filled with specialised discourse features, and ultimately demotivating due to the level of technical expertise needed to participate in gameplay. From such criticisms aimed at digital games, we argue that board games offer superior opportunities for authentic communication, and both affective and cognitive benefits when used as part of a rigorous teaching methodology.

In today’s workshop our goals are:

to educate practitioners on the range of available board games and their specific affordances for language learning from a sociocultural perspective.

to reveal our framework for using board games as a core component in EFL contexts with a specific consideration on fostering verbal interaction. This includes an extensive pre-play stage utilising YouTube "gameplay" videos and other online resources.

The workshop was divided into three sections which allowed us to first of all let people experience the Kotoba Rollers framework for themselves, then we went over the theoretical underpinnings that helped shape the development of the framework. Finally, we held a Q&A session to get feedback and to help clarify parts of the framework that might not have been so salient/required further explanation.

Experience

The first part of the workshop was for the attendees to experience the framework. We gave them five minutes to read through the rules to 2 Rooms and a Boom and create questions based on those rules in order to check understanding with the other participants. In other words, they quizzed each other on the rules that they had just read to make sure that the game rules were known to all participants.

Upon completing this stage, they played through the basic version of the game themselves. We weren’t graced with the luxury of being able to send players between rooms, so we used the room for the presentation and the corridor (I apologise to the other presenters for the ruckus we caused..!)

Upon completing the play phase, we went through all three post-task report sheets (verbally) to debrief (or reflect) on the activity we had just done by asking questions such as: What words had come up again and again? Who won? What were the best tactics?

Framework explanation

After the experiencing the framework for themselves, it became much easier to show them the theoretical considerations that underpin the development. The main theories being Task Based Language Teaching and Sociocultural Theory. You can see an outline of the model in this post. The only new item regarding the framework is the addition of a reference to Long’s (2014) Methodological Principals and the extent that we are adhering to them.

MP1 - Use task not text YES

MP2 - Promote learning by doing YES

MP3 - Elaborate Input NO

MP4 - Provide rich input YES

MP5 - Encourage chunk learning NO

MP6 - Focus on form SOMEWHAT

MP7 - Provide negative feedback SOMEWHAT

MP8 - Respect learner syllabi and development process SOMEWHAT

MP9 - Promote cooperative learning YES

MP10 - Individualise instruction NO

These points require more explanation, and will become the topic of a future blog post.

Q&A Session

The final Q&A session allowed the participants to ask questions about the framework, and posit any concerns they might have. Generally, we felt that questions were not so much criticisms, but requests for additional information on how the framework works in practice and suggestions for implementation in their own contexts. One questions was regarding which games we recommend, so I see a “Kotoba Rollers recommends…” post coming.

One participant mentioned fairly obviously that

This framework would work with people that like games.

which is totally fine. Much in the same way that an English designed to be taught through the reading and discussion of classic literature would work with students that are interested in that subject.

However, I would argue that the number of students that are interested in games versus those that are interested in classic literature, or even more “popular” topics such as movies, music, sports, etc. would be less than those that play games. Gaming is the real unifying factor amongst students (especially at my science and tech university…), which provides support for the use of games as a teaching tool. Why? Because students are familiar with and motivated to learn with this media. But that’s for another blog post, too.

Conclusion

Our workshop at JALT CALL went as well as we hoped and we able to both inform others of the power of games in the classroom, but also generate a discussion on what the implications of doing so are.

I do not plan on doing any more presentations regarding Kotoba Rollers this year, but am deep in the process of writing a paper on students perceptions of this framework, and also planning a revised version ’Framework 2.0’ based on student feedback for use in the autumn semester later this year. I have a lot to talk about regarding the revised framework, and will be updating this blog with details also.

As always, thanks for reading and I appreciate any questions you may have.

James / ちーぷ

#board game syllabus#kotoba rollers#EFL#Japan#JALTCALL#workshop#game based learning#GBL#game based language learning

0 notes

Photo

Presentaton flyer

I will be doing a presentation at my university next Friday all about the Kotoba Rollers project.

Slides to follow.

0 notes

Text

What is Kotoba Rollers?

0 notes

Text

Future of Kotoba Miners

Meeting with Kai

Let’s start out with a paragraph about how amazing Kai is.

Kai is a fantastically deep thinker and has a great intellect, so it was a real pleasure to be working with someone of that intellect. His passion for knowledge and his dedication to improving himself as an engineer and human is really infectious. I’m indebted to him for all his help inspiring me, pushing me, working with me.

TL;DR, the guys is amazing!

Brainstorming

I met with Kai on Saturday and we talked widely and deeply about the future of Kotoba Miners. We started out brainstorming ideas related to - second language acquisition, - Player goals, - Research goals, - The strong points of virtual worlds, - Minecraft… - etc.

Needless to say, we really squeezed as many ideas out of our brains as possible.

The issue with Kotoba Miners as it is now is quite clear to Kai:

The goal of Kotoba Miners is strongly aligned with player goals, and not research goals.

I have to admit, I had never considered this before and this really opened my eyes. Let me explain what this means in more detail.

Player goals vs Reseach goals

Player goals are simple: Learn Japanese/English. In order for the players to achieve this I created the JP course, did weekly lessons, manga reading classes, Let’s Play sessions, and other such one off activities, which is great if you are a learner. The problem is, I wasn’t collecting data from this. Data that could be used to write an essay or research paper. I was instead caught up in the “busy work” of running an online language school, a Minecraft server, and a community of players.

Research goals are also simple: Use Kotoba Miners as a place to gather empirical data towards writing a paper. What kind of paper? The kind that provides evidence to show the efficacy of the server in terms of language learning benefits, be that in terms of improving listening, reading, writing or speaking skills, cultivating communicative competence, social awareness, cultural competence, etc.

So how do we get the focus back on research?

From that, we thought more specifically about the goals of the server from a research perspective. And, to cut a long story short, we will work together to create an online learning community that is driven by the players themselves. From a constructivist approach to language learning, we provide the tools for players to engage in self-driven learning.

OK…?

We are going to make use of Kai’s Virtual RyuuGaku (Ryuugaku means “study abroad”) (henceforth: VRG) software. It has a lot of strong points, particularly when it comes to teaching reading and writing skills. Here is a messy diagram of what we wrote about VRG:

The basic VRG system is designed to get learners to create NPCs as part of a wider role-play based course for learning a foreign language (EN/JP). These NPCs will be able to talk and quiz other players that come into contact with them. Other players interact with the NPCs and do the assigned quizzes, then they may leave comments or corrections.

As you can see then, the type of interaction is going to be generally asynchronous and focused on reading and writing. But don’t give up hope yet. We have some tricks up our sleeves.

Framework

For me, creating a rigorous teaching methodology is paramount. My MA., PhD., and #KotobaRollers project all has some element of syllabus, task, or framework design involved.

So what is the framework for this project?

My background is in task-based language teaching (TBLT) (the “soft” approach to TBL in case other practitioners are reading). This way of teaching basically has three stages:

Pre-task (learn about the task)

Task (do it)

Post-task (reflect on what you did)

During the pre-task phase learners are primed with examples of the target, watch videos of native speakers doing similar tasks, and generally activate their brains and linguistic knowledge ready to do the task ahead of them. The task itself is designed with a non-linguistic goal that may require the use of a specific linguistic item (directions, prepositions. greetings etc.) in order for learners to complete it. The post-task phase can be used to talk about grammar that came u@ in the task, other problems, a personal reflection, discussion with others about the task, etc.

OK, so now that TBLT is a little more salient, let’s look at the kind of framework VRG will use (this is still very early in production mind you). I will be using the specific task of - booking in at a hotel: a task that would seem important to foreign travellers.

Pre-task

Learn about the particular setting via a teacher-created hotel featuring NPCs that interact with you. Essentially, you can think of this as a native speaker doing a similar task for learners to become accustomed to the vocabulary and target grammatical items.

Brainstorm words that you think may be useful in this particular role play setting. In this case: reservation, credit card, bellboy, front desk, receptionist, etc. The brainstorming session will be carried out in an area in Minecraft. Maybe something simple like having signs on a wall for players to place words or other grammatical items. Essentially, a shared brainstorming section.

Task

The task that we have in mind right now is the creation of an area to show off your own NPC that shows that you have grasped the language knowledge presented in the teachers model (and to a certain extent show off your own personal design flair).

Post-task

The post task phase is a place for players to talk about the creations made as part of the original task. This could be a few different things:

Comments on others creations (いいね! That’s great! or something similar…)

Suggesting corrections on vocabulary, grammar, cultural artefacts that the learner hasn’t understood properly, etc.

A question to that learner regarding the NPCs or the building it is in.

Carrying out the same role-plays in pairs or small groups (real time, spoken communication).

Next steps

Develop develop develop

The idea is to create stages for players to make role-plays in a similar structure to the Genki I textbook. The first role-play will thus be a “greetings” skit.

Playtest playtest playtest

Once this (and the technical side of things) is complete we will test it as admin and with a few, select members. After this stage we will create more content and then reveal our proposal to the public.

I will keep updating this blog with progress reports, but for those that are more interested, get on the Kotoba Miners server in the evenings (Japan time) to see Kai hard at work on developing the NPC plugin. Alternatively, subscribe to this blog, follow us on Twitter @cheapshot and @kai_f__

Disclaimer

This project is still very early in its development cycle. The technical side of things is progressing at a fast rate, but as for the implementation, we are not sure when this will be ready. The bottleneck is me (Cheapshot) to be honest. I have a lot of other projects on-going at the minute, the main one being my PhD, and I really want to get this finished first before I commit to another Kotoba Miners project.

Thanks for your continued support with the Kotoba Miners project, and if you have any comments or suggestions, please don’t hesitate to do so below.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Kotoba Rollers: Example Worksheet

This is an example worksheet for learning about the game Forbidden Island.

Part 1: Learn the rules (Reading)

Here is a link to the rule book.

Part 2: Watch a video explaining the rules (Listening, writing)

Here is a video of how to play the game and a review. (First 20 minutes only

After looking at the rulebook and watching the video, please write 10 questions about the game to give to your group members next class.

________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________

Part 3: Watch a video of this game being played (Listening, writing)

Please watch some of these videos:

Here is a gameplay video for you to watch.

And one more (father and son play)

You can also search YouTube to find more videos with:

Let’s Play Forbidden Island

Write down any useful expressions you hear on the Useful Phrases worksheet!

0 notes

Text

Board games and language learning: The Framework

Merry Christmas everyone.

Today is Boxing Day in the UK, and I’ve been awake since 4am with the kids. Jet lag is scary.

Time to roll out a post about the framework I am using. This will be a quick overview of all the main points, how they relate to each other, and how I plan on improving it in the future. The framework is comprised of three main sections: Pre-play, Play, and Post-play. Here is what it looked like at the theoretical, planning stage.

Pre-play (at home)

Learn the rules (via the rulebook)

Learn the rules (via video)

Watch the game being played

Create comprehension questions

Pre-play (in the class)

Comprehension check

Teacher-led Q&A session

Play

Play the game

Post-play

Review useful vocabulary and grammar

Debriefing (Class-wide Q&A session)

Focus on form

Report

This set up is based loosely on the teaching approach known as Task-based Language Teaching (henceforth: TBLT). The simple idea is that students are exposed to comprehensible input (the rule book) and native speakers modelling the target language (game play videos) to provide students with the tools that they will need to play the game themselves during the play phase. Following play, it is considered important to “debrief” students about what they have done and focus on understanding what happened in the game, as well as focusing on any linguistic difficulties they had.

OK, I will pull out a few sections of the framework here to explain the rationale for their inclusion and to give more detail to the inner workings.

Pre-play (Outside of the classroom)

The model starts with students learning the game rules and familiarising themselves with how to play the game. This prepares them for the play by exposing them to target vocabulary and grammatical structures that will be needed during gameplay. There are a number of reasons for requiring students to learn game rules before class; one being the temporal issue of the amount of time that can be dedicated to rule explanation during class time. However, more importantly is the notion of investment.

Unlike a teacher-led, whole class rule explanation, when students are put in charge of learning for themselves, they may choose a variety of activities to best meet this goal. Some may prefer to read the provided rule book, others may prefer to watch video explanations, and others may enjoy watching the game in action. By providing students with a number of tools to achieve the same goal, we are promoting student agency, and getting them to invest themselves in the process of learning.

I’d like to focus specifically on this part of pre-play:

Part 1.4: Create comprehension questions

Before coming to class learners are told to create 10 comprehension questions regarding the game rules. Learners are expected to know the answer to the questions they write. These questions are used at the start of the play session during class time. If we take the board game Monopoly as an example, a comprehension question could be:

Q: How much money do you get when passing GO?

A: $200

The reason I focused on this section is because in the latest version of the framework, this section has been reversed. Instead of students making questions themselves, I have decided to make my own questions and get students to answer them for homework.

Why the change?

Based on my observations of what kind of questions students were bringing to class, I found that generally (and this links to Reflection: Part 2 regarding student ability/willingness to participate), students were writing very simple, surface-scraping questions that didn’t really get at the heart of the rules, which meant that they were coming to class unprepared. By requiring them to answer questions that I (as someone who has played all the games and understands what they need to be aware of to succeed) deem important to answer, they are much more prepared to play effectively. Additionally I can guide their focus to specific words or phrases that they will rely upon when playing.

[Aside]

Just thinking about this now, but an additional change to the framework could see students writing their own comprehension questions for future players of the game as part of their final reflection.

Pre-play (In class)

Part 2.1: Comprehension check

At the start of the class, students quiz each other on the game rules using the comprehension questions they made in Part 1.4.

Part 2.2: Teacher-led rule check

Upon completing the student-centred comprehension check, a teacher-led session may be held.

Play

Part 3.1 Play the game

The main task of this framework is the gameplay session. Games are selected based on their ability to encourage communication between players. Students will have to work together as a group regardless of the game’s theme (competitive, cooperative, team-based, etc.) During play, learners are encouraged to write down any words they hear from their peers on the Useful Phrases Sheet they used during activity Pre-play 1.3.

Part 3.3: Debriefing

Debriefing is a term that has been used since the 80s to describe a post-play session which allows participants to reflect on the activity. The phrase is not specific to language learning contexts, however, it does appear most frequently in studies involving the use of games or simulations in educational contexts. Origins of the phrase originate in Dewey’s (1916) concept of learning as a combination of experience and reflection. The term “reflection,” then, being re-coined as “debriefing” here.

Post-play

Part 4.1: Focus on Form

Following, the teacher leads a session looking at linguistic forms. Preparation for this section can be achieved by carrying out Part 1.3 and making a note of grammatical forms that appear frequently. Alternatively, as is often the case with TBLT, instructors may wish to create an incidental focus on form section based on observations during the play session.

Part 4.2: Report and reflection 1

At this stage, we shift focus from fluency to accuracy. Learners are required to complete one of three different report sheets that we created. The sheets promote students to focus on different aspects of the gameplay activity. The worksheets were designed based on those used in the Brooklyn Game Lab, but with an increased attention on language learning. Each time students finish playing, they are directed to choose a different worksheet to complete.

Report sheet 1: Winning conditions

Regardless of who won the game, this worksheet requires learners to write about strategies and tactics that can be used to succeed at the game. For games that do not feature a winning condition for a specific player, such as the aforementioned Pandemic, learners may write about strategies that they used as a group and whether they were successful.

Report Sheet 2: Useful language

The second worksheet promotes learners to focus on the linguistic properties of the game they played. They are required to write out both specific vocabulary items with a focus on why they are important to play, as well as key phrases and expressions.

Report sheet 3: Critical thinking

The third worksheet promotes learners to consider the transferability of linguistic elements they encountered during gameplay.

Extended post-play

Although not part of the weekly, repeatable framework, we have designed extended tasks for student reflection and participation in developing a culture around this framework. These are yet to be fully implemented but we feel that to help low level learners get the most out of this framework, they could do such activities as:

write a short rule book

make gameplay videos

Writing a simplified rulebook would be useful for the writer in that they are able to demonstrate their understanding of the game, and for future players in getting the bulk of the rules in a language that is appropriate to their level. In other words, the native English rule books contain a great deal of advanced vocabulary, and can be quite intimidating to new players. Having a simplified version would be a great gateway into the game. Likewise, the gameplay videos of native English speakers are often very fast, contain a lot of slang, and generally difficult for low level learners to follow. Creating student-made videos would accomplish at least two things:

Allow players to reflect on their play session, and focus on linguistic accuracy.

Show future students that yes, it is possible to play this game in English! I.e. give students a confidence boost in knowing that their peers have been able to complete this activity in English.

Updated framework

Finally, then, it is important to mention that the framework is still in an unfinished state that is being improved upon. It currently looks like this:

Pre-play (at home)

Learn the rules (via the rulebook)

Learn the rules (via video)

Watch the game being played

Answer comprehension questions

Pre-play (in the class)

Check comprehension question answers

Play

Play the game for 10 minutes

Change a rule (“If I speak Japanese…”)

Continue playing

Post-play

Review useful vocabulary and grammar

Write a report

Language focus

If the students choose to play the same game the following week (which is definitely an option), the framework changes to:

Pre-play (at home)

Reflect on previous play, and write phrases/words that will help you play using more English next time.

Pre-play (in the class)

Rule check

Share phrases with the group

Play

Play the game for 10 minutes

Change a rule (“If I speak Japanese…”)

Continue playing

Post-play

Review useful vocabulary and grammar

Write a report

Language focus

I hope that put some light on the actual framework. Like I mentioned in a previous post, we are hoping to publish a longer version of this early 2016.

Thanks for reading as always.

0 notes

Text

Reflection Part 4: Adapting the framework

Part 1: Types of games and language skills

Part 2: The need to adapt game rules

Part 3: The classroom experience as meta-game

In my last post I talked about applying a band-aid (I really want to say plaster here, but for the sake of the international audience, we’ll stick to band-aid) to the meta-game of “English class” by micromanaging—or “adapting”—the rules by which students play games. The new set up looks like this:

Yes, I know my writing is scruffy. Yes, I know that last sentence isn't really a sentence... The addition here is that as part of the framework, I am asking students to stop what they are doing after a 10 minute “getting used to the game” period, and to think about how they can improve the rules of the game to help them speak more English.

But why do they need to be pushed this way?

This is something that I have bee wrestling with internally. In an ideal world, I wouldn’t need to add this additional rule. In an ideal world, the students would be motivated to learn English, have the ability to realise what is required of them and get to it without external pressures or reminders. But this is not an ideal world.

I believe there is a lot to be gained by adding this new section to the framework. (Again, I’m not trying to say that this applies to all students, but…) It pulls them out of their mindset of “I came here today to play a board game,” and pushes them instead to reconsider the goal of the class: to speak English. And, yes, some students do need to be reminded of that. And can you blame them? Not really. They are in a monolingual class comprised of friends that they speak to in their native language all the time. It probably feels very embarrassing to be speaking a foreign language in front of them. And don’t get me started on the Japanese mentality towards making mistakes…

By having a very specific reason for trying and failing at speaking English (something like: “If I speak Japanese, the whole table, board game included gets flipped”), students may feel relieved that they are allowed to mess up. In other words, they have an additional reason to use English. A reason affiliated with something that they are already invested in, like not getting an outbreak in Taipei.

[York thinks about this a little more]

Or could it also have the reverse effect? “I don’t want to speak English, but now I am forced to, and if I make a mistake, I have to give up a resource to the opponents.” OK, this is something I’m going to have to collect data on.

[OK, added a question regarding this in their end of year report. Data data data!]