Text

I haven’t been able to post much lately as there has been so much going on! One thing I’ve done over the last couple of years is start a green burial products business with my fabulous sister. I’ve managed to incorporate some medievalism in there via this blog post, and more death history blogs to come!

https://heburials.com.au/blogs/news/a-brief-history-of-western-women-in-deathcare

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you get an opportunity to go through the British Library digitised manuscripts, don’t miss this one! So many hilarious and bizarre images!

Harley MS 6563

Date c. 1320-c. 1330

Title: Book of Hours (fragmentary)

httpss://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?index=4&ref=Harley_MS_6563

Here were my favourites:

1. I love her sassy face. They believe she represents the sin of avarice.

2. Woman playing the tambourine

3. Woman fighting with distaff

4. Woman fighting with sword

5 & 6. Nude warriors

7. Woman grieving at a tomb

8 & 9. Medieval killer bunnies, because they make me happy.

266 notes

·

View notes

Text

I haven’t been able to post much lately as there has been so much going on! One thing I’ve done over the last couple of years is start a green burial products business with my fabulous sister. I’ve managed to incorporate some medievalism in there via this blog post, and more death history blogs to come!

https://heburials.com.au/blogs/news/a-brief-history-of-western-women-in-deathcare

#medieval women#middle ages#medieval art#medieval death#death#green burial#medieval history#14th century#15th century

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

A poor quality image but I still love this one of women sewing a corpse into a shroud from a 15th century book of hours. Preparing and shrouding the corpse was traditionally the role of women in Western culture until the late 19th/early 20th century.

#middle ages#15th century#shrouding#death care#medieval history#medieval art#medieval women#medieval#medieval death

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ah how I love the Trotula!

——————

On excessive flux of the menses

29. Sometimes the menses abound beyond what is natural, which has happened because the veins of the womb are wide and open, or because sometimes they break open and the blood flows in great quantity. And the flowing blood looks red and clear, because a lot of blood is generated from an abundance of food and drink; this blood, when it is not able to be contained within the vessels, erupts out.

31. The cure. If, therefore, the blood is the cause, let it be bled off from the hand or the arm where the blood is provoked upward. Any sort of gentle cathartic ought also to be taken.

34. Let her eat hens cooked in pastry, fresh fish cooked in vinegar, and barley bread. Let her drink a decoction made from barley, in which great plantain root is first cooked, and boil it with the decoction and it will be even better. And afterward boil [the root] in seawater until it cracks and becomes wrinkled, and let vinegar be added and let it be strained through a cloth and let it be given to drink. Let her drink red wine diluted with seawater. And if great plantain root is boiled with the decoction, so much the better.

43. In another fashion, take shells of walnut and make a powder and give it in a drink with seawater. Then make a plaster of the dung of birds or of a cat [mixed] with animal grease and let it be placed upon the belly and loins.

—————

From ‘Women's Lives in Medieval Europe : A Sourcebook’ edited by Emilie Amt (Taylor & Francis Group, 2010).

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Snippets from the introduction of a recent essay I wrote on women and gender in the crusades:

Besieged in Jerusalem in 1187, Margaret of Beverly proved herself an active participant in the crusades by patrolling the walls, describing herself as ‘a fierce warrior woman’.

Crusading was unmistakably gendered with socially constructed, rather than biologically determined, masculine and feminine roles. Participation was geared towards men, narratives favoured male exploits and contemporary gender constructs dictated women should merely support and encourage the masculine pursuit of warfare.

Despite being discouraged and marginalised, many women joined the crusade as pilgrims and camp followers where they provided services such as moral support, menial labour, cookery and prostitution. They assisted with siege warfare, defence and the provision of supplies to frontline fighters. In emergencies, noblewomen took leadership roles and lay women likely took part in direct combat. Those left at home took on the challenging burden of managing families, estates and businesses to facilitate the absence of male relatives.

Women within the army and crusader settlements faced a myriad of grave dangers including starvation, captivity, rape, family separation, injury and death.

The contribution of women to crusading was significant and varied, but the tendency to define a ‘crusader’ only as a direct combatant has led some historians to suggest only women who fought could be considered crusaders. As the crusades were a spiritual and societal movement as well as a military enterprise, I argue it is more appropriate to define a crusader as a participant. It is oversimplified to ignore the vast contribution of women who, like their male counterparts, took vows and committed to the Christianisation of the east at great personal risk. Therefore, I argue women should be called crusaders for their dedication, courage and sacrifices for the crusade effort.

Image is of Melisende of Jerusalem

#crusades#women in history#12th century#13th century#middle ages#crusader states#herstory#warrior women

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

“There were once women in Denmark who dressed themselves to look like men and spent almost every minute cultivating soldiers' skills; they did not want the sinews of their valor to lose tautness and be infected by self-indulgence. Loathing a dainty style of living, they would harden body and mind with toil and endurance, rejecting the fickle pliancy of girls and compelling their womanish spirits to act with a virile ruthlessness. They courted military celebrity so earnestly that you would have guessed they had unsexed themselves. Those especially who had forceful personalities or were tall and elegant, embarked on this way of life. As if they were forgetful of their true selves they put toughness before allure, aimed at conflicts instead of kisses, tasted blood, not lips, sought the clash of arms rather than the arm's embrace, fitted to weapons hands which should have been weaving, desired not the couch but the kill, and those they could have appeased with looks they attacked with lances.”

~ Saxo Grammaticus in Gesta Danorum c1200 CE

#medieval women#viking women#shield maidens#warrior women#saxo grammaticus#gesta danorum#middles ages

333 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some interesting tidbits on the penalties for cross-cultural sex in 13th century Spain from ‘The Crusades: A Reader’, edited by S.J. Allen and Emilie Amt.

#13th century#cross-cultural relationships#medieval law#medieval women#spain#middle ages#women in history

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

An interesting segment on medieval Muslim women from the Memoirs of Usamah Ibn Munqidh in ‘The Crusades: A Reader’, edited by S.J. Allen and Emilie Amt

I love the feisty old woman! ✊🏽

#medieval women#muslim women#medieval muslim women#12th century#12th century women#crusades#crusader states#usamah ibn munqidh#kickass woman#herstory

75 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tamar the Great

Queen of Georgia

Born c. 1160 – Died 1213

Claim to fame: The first woman to rule Georgia in her own right, Tamar presided over the apex of the ‘Georgian Golden Age’, a period of political, military and cultural achievements

As a teenager Tamar became co-ruler of Georgia with her father Giorgi III from 1178 until his death six years later. Although named as heir she faced significant opposition from the aristocracy upon commencing autonomous rule. With diplomacy and concessions Tamar was able to secure her throne. The nobles quickly arranged for her to marry a Russian prince, Yuri, but the marriage was not happy. Tamar’s increasing strength and assertiveness meant that she was able to divorce her drunk and debauched husband and expel him from Georgia. Yuri then attempted two large-scale coups, both of which were put down. Tamar then chose a capable military commander, David Soslan, to be her second king consort and she continued to be styled as mep’et’a mep’e, “king of kings”. Tamar and David had a son and a daughter who both became rulers of Georgia.

Once Tamar succeeded in consolidating her power she looked to increase it by repulsing attackers and reducing nearby regions into tributary states. She used her troops to support the establishment of the empire of Trebizond, thus creating a friendly region that was formerly controlled by the Byzantine Empire. Tamar took advantage of the weakness of the Byzantines to position Georgia as the protector of eastern Christians, supporting religious institutions throughout the eastern Mediterranean. Tamar accompanied her army and was involved in campaign planning but she was never directly involved in the fighting. Despite this the military victories of her reign contributed to her image as a warrior-queen.

Tamar’s leadership brought the Georgia to the zenith of its “Golden Age”, a period of political, economic and cultural might. Her greatly expanded kingdom brought new wealth to the country and enabled a unique Georgian Christian culture to flourish, along with military, industrial, commercial, literary and architectural triumphs.

Tamar died of a “devastating disease” in 1213 and there is continuing speculation about the site of her burial. The Georgian writer Grigol Robakidze wrote “Thus far, nobody knows where Tamar’s grave is. She belongs to everyone and to no one: her grave is in the heart of the Georgian”. Though sometimes portrayed as cruel and seductive, Tamar’s legacy is now mostly that of a pious and merciful queen (she opposed torture, mutilation and executions) who has since been canonised by the Georgian Orthodox Church.

Sources: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8.

264 notes

·

View notes

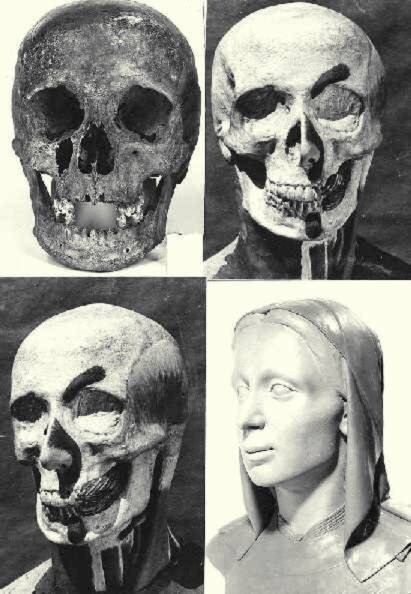

Photo

Facial Reconstruction of Agnes of Antioch

Queen Consort of Hungary

Born 1154 – Died c.1184

Agnes was the daughter of Constance, Sovereign Princess of Antioch and Raynald of Châtillon. She became the first wife of Béla III of Hungary.

Her intact tomb was accidentally discovered during the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 which has allowed her remains to be studied and her appearance reconstructed.

Factoid: Agnes was the great niece of Queen Melisende of Jerusalem (more on Melisende to come soon).

Sources: 1. 2.

More images.

391 notes

·

View notes

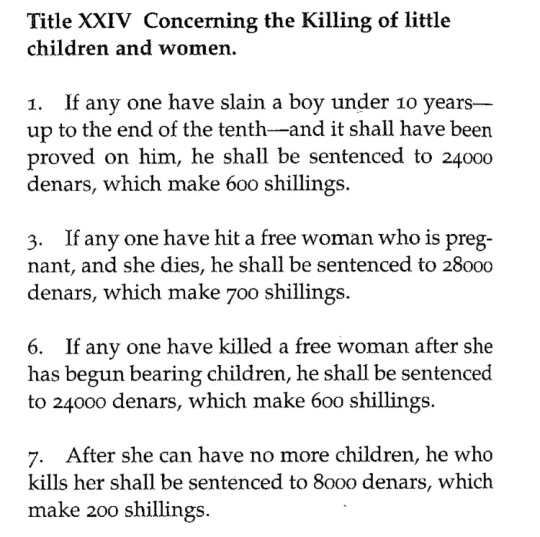

Photo

It’s fascinating (and horrifying) to me that under Salic Law a woman’s worth was entirely linked to her ability to bear children.

Women in Salic Law

Excerpts regarding the treatment of women from the Lex Salica (Salic Law), the civil law code compiled around the time of King Clovis (roughly 500 C.E.) for the Salian Franks.

462 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Duke Amalo sent his wife to another estate to attend to his interests, and fell in love with a certain free-born girl. And hen it was night and Amalo was drunk with wine he sent his men to seize the girl and bring her to his bed. She resisted and they brought her by force to his house, slapping her, and she was stained by a torrent of blood that ran from her nose. And even the bed of the duke mentioned above was made bloody by the stream. And he beat her, too, striking with his fists and cuffing her and beating her otherwise, and took her in his arms, but he was immediately overwhelmed with drowsiness and went to sleep. And she reached her hand over the man's head and found his sword and drew it, and like Judith Holofernes struck the duke's head a powerful blow. He cried out and his slaves came quickly. But when they wished to kill her he called out saying: "I beg you do not do it for it was I who did wrong in attempting to violate her chastity. Let her not perish for striving to keep her honor." Saying this he died. And while the household was assembled weeping over him the the girl escaped from the house by God's help and went in the night to the city of Chalon about thirtyfive miles away; and there she entered the church of Saint Marcellus and threw herself at the king's feet and told all she had endured. Then the king was merciful and not only gave her her life but commanded that an order be given that she should be placed under his protection and should not suffer harm from any kinsman of the dead man. Moreover we know that by God's help the girl's chastity was not in any way violated by her savage ravisher.”

~ Gregory of Tours

Historia Francorum IX:27, 6th century CE

#6th century#merovingian#gregory of tours#rape#herstory#middle ages#early medieval women#early medieval#self defense#sexual assault#abduction#medieval women#medieval history#women in history#history#historia francorum#history of the franks#the franks

79 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Newly discovered portrait of Elizabeth I by Steven van der Meulen

“This newly discovered and hitherto unrecorded portrait is an important addition to the iconography of Elizabeth I, being a rare early depiction, dating from circa 1562, and is thus one of the first known sophisticated images of Elizabeth as Queen.”

https://www.bonhams.com/auctions/25231/lot/26/

827 notes

·

View notes

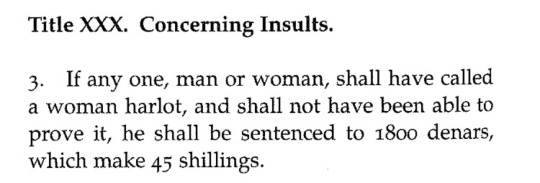

Photo

Fredegund

Queen Consort of Neustria (western Francia)

Born ? - Died 597 CE

Claim to Fame: A brutal and formidable queen, best know for her forty year feud with her sister-in-law, Queen Brunhild of Austrasia.

Background: High-ranking women in Merovingian Gaul could hold substantial wealth and status in the fifth and sixth centuries which enabled them to exercise significant social, political and religious influence.

Born into a low-ranking family, Fredegund was a servant to the first wife of King Chilperic I of Neustria, Audovera. She seduced Chilperic and convinced him to divorce and expel Audovera. Chilperic then married a wealthy second wife, Galsuenda, but she soon died and was swiftly replaced as queen by Fredegund. Stories of Galsuenda’s death vary but it is believed that she spoke out against the immorality of Chilperic’s court so the King and his favourite mistress, Fredegund, had her strangled in bed. The powerful Queen Brunhild of Austrasia was both the sister-in-law of Chilperic (she was married to his brother) and the sister of Galsuenda. Brunhild’s fury at her sister’s death sparked a feud between the once unified houses of Austrasia and Neustria that spanned over forty years. The rivalry between Brunhild and Fredegund was particularly bitter and lead their families through generations of conflict.

Fredegund is represented in primary sources as a particularly violent woman who used her desirability to manipulate and corrupt those around her. She frequently contracted assassins as well as torturing, maiming and killing opponents. Among her many alleged misdeeds, Fredegund was suspected of ordering the assassination of Brunhild’s husband, Sigebert I, and attempting to assassinate Brunhild’s son Childebert II, her brother-in-law Guntram of Burgundy, and even Brunhild herself. In a jealous rage, she even attempted to murder her own daughter, Rigunth, by slamming the lid of a chest down on her neck as she reached for the jewelry inside. However, her violence was not limited to royal family members, and included a number of officials, clergymen and locals. In a classic example, Fredegund attempted to quell a dispute between kinsmen but ‘when she failed to reconcile them with gentle words she tamed them on both sides with the ax’ by inviting them to a feast and having them all murdered. Her formidable reputation served her well and she manipulated all levels of society through the fear of her fury.

When a dysentery epidemic struck her husband and two of her sons in 580 CE, Fredegund was plunged into remorse. Believing the epidemic was punishment for her sins, she burned unfair tax records and donated to the church and the poor after her sons succumbed to the disease.

In 584 CE, her husband, Chilperic, was mysteriously assassinated and Fredegund sought refuge in the Notre Dame de Paris cathedral. She died of natural causes 8 December 597 in Paris and is entombed in Saint Denis Basilica.

Several years after Fredegund’s death, her son Clothar II defeated Brunhild in battle and, despite the Queen being in her late sixties, he had her stretched on the rack for three days and then torn apart by four horses. Such was the bitterness of their familial enmity.

Note: The main source for Fredegund’s life is Gregory of Tours’ History of the Franks. Gregory was patronised by Queen Brunhild so his depictions of her qualities and the evils of her rival, Fredegund, are likely biased. Other sources recognise Fredegund’s brutality but treat her and Brunhild more equitably.

~ Much of this mini-bio is based on an essay of mine, so please PM me for sources.

855 notes

·

View notes