Text

Ditto! Though I can think of scarier options too…

Reblog and the national convention sends Augustin Robespierre to your town, ignore and they send Collot d'Herbois

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

#history#primary sources#historiography#it’s hard work but someone’s gotta do it#historians#that rely mainly on secondary sources#naive or lazy historians that take primary sources at face value!

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fascinating. From Robespierre’s deputy Headmaster. To be treated with caution, as always! Would like to know more about Herivaux

Abbé Proyart on the childhood on Robespierre

Source: La Vie et les crimes de Robespierre, surnommé Le Tyran: depuis sa naissance jusqu’à sa mort (1795) by Le Blond de Neuvéglise (abbé Proyart) page 19-51

Maximilien Robespierre was born in Arras in 1759, and was baptized in the Church of St. Aubert, his parish. His father was Maximilien Robespierre, a lawyer with little occupation at the Superior Council of Artois; and his mother Marie-Joseph Carreau, daughter of a beer brewer from the same town. He had a younger brother, who followed him in the career of crime and even to the scaffold. He had two sisters, one of whom died young. She who survived had had the advantage of a religious education from which she profited. But, as the mediocrity of her fortune kept her entirely dependent on her brother, she found herself obliged to go and live with him in Paris; and we don’t know what she might have become at the school of such a teacher. What would nevertheless appear to be in her favor is that her brother, at the time of his greatest fury against his Compatriots, chased her out of the house, and forced her to go and beg for an asylum in the town of Arras where she now lives.

Keep reading

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fantastique!

The other day, whilst perusing the Louvre's collection, as one occasionally does, in search of 18th-century artefacts, I chanced upon a delightful set of six glasses dating back to the late 1700s (https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010381445). Of course they caught my eye since I love silhouettes as an art form...

So, behaving as any sensible individual might, I felt a sudden urge to acquire some for myself. Given that I can't exactly march into the Louvre and demand they hand over their glasses, and finding myself in urgent need of a weekend project, I decided to craft my own. And, well… one "brilliant" idea gave way to another, leading to… a ridiculous number of botched attempts, culminating in the creation of my new Robespierre mug ☕️💖

(the man was reputed to subsist almost entirely on coffee... so of course I made a mug...)

Now I want to make one for each member of the 3rd CPS and have them have coffee parties ...

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

I understand the story of marat and his assassination event

But who is lepeletier?

Because I saw a drawing for him by louis David and I learned about his death which happen to be the same as Marat so yeah .. I wanna know about him.

According to the biography Michel Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau, 1760-1793 (1913), its subject of study was born on 29 May 1760, in his family home on rue Culture-Sainte-Catherine, a building which today is the Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris. His family belonged to the distinguished part of the robe nobility. At the death of his father in 1769, Lepeletier was both Count of Saint-Fargeau, Marquis of Montjeu, Baron of Peneuze, Grand Bailiff of Gien as well as the owner of 400,000 livres de rente. For five years he worked as avocat du roi at Châtelet, before becoming councilor in Parliament in 1783, general counsel in 1784 and finally taking over the prestigious position of président à mortier at the Parlement of Paris from his father in 1785. On May 16 1789, Lepeletier was elected to represent the nobility at the Estates General. On June 25 the same year he was one of the 47 nobles to join the newly declared National Assembly, two days before the king called on the rest of the first two estates to do so as well. A month later, during the night of August 4 1789, he was in the forefront of those who proposed the suppression of feudalism, even if, for his part, this meant losing 80 000 livres de rente. Four days later he wrote a letter to the priest of Saint-Fargeau, renouncing his rights to both mills, furnaces, dovecote, exclusive hunting and fishing, insence and holy water, butchery and haulage (the last four things the Assembly hadn’t ruled on yet). When the Assembly on June 19 1790 abolished titles, orders, and other privileges of the hereditary nobility, Lepeletier made the motion that all citizens could only bear their real family name — ”The tree of aristocracy still has a branch that you forgot to cut..., I want to talk about these usurper names, this right that the nobles have arrogated to themselves exclusively to call themselves by the name of the place where they were lords. I propose that every individual must bear his last name and consequently I sign my motion: Michel Lepeletier” — and the same year he also, in the name of the Criminal Jurisprudence Committee, presented a report on the supression of the penal code and argued for the abolition of the death penalty. After the closing of the National Assembly in 1791, Lepeletier settled in Auxerre to take on the functions of president of the directory of Yonne, a position to which he had been nominated the previous year. He did however soon thereafter return to Paris, as he, following the overthrow of the monarchy, was one of few former nobles elected to the National Convention, where he was also one of even fewer former nobles to sit together with the Mountain. In December 1792 he started working on a public education plan. On January 20 1793, he voted for death without a reprieve and against an appeal to the people during the trial of Louis XVI (Opinion de L.M. Lepeletier, sur le jugement de Louis XVI, ci-devant roi des François: imprimée par ordre de la Convention nationale). After the session was over, Lepeletier went over to Palais-Égalité (former Palais-Royal) where he dined everyday. The next day, his friend and fellow deputy Nicolas Maure could report the following to the Convention:

Citizens, it is with the deepest affection and resentment of my heart that I announce to you the assassination of a representative of the people, of my dear colleague and friend Lepelletier, deputy of Yonne; committed by an infamous royalist, yesterday, at five o'clock, at the restaurateur Fevrier, in the Jardin de l'Égalité. This good citizen was accustomed to dining there (and often, after our work, we enjoyed a gentle and friendly conversation there) by a very unfortunate fate, I did not find myself there; for perhaps I could have saved his life, or shared his fate. Barely had he started his dinner when six individuals, coming out of a neighboring room, presented themselves to him. One of them, said to be Pâris, a former bodyguard, said to the others: There's that rascal Lepeletier. He answered him, with his usual gentleness: I am Lepeletier, but I am not a rascal. Paris replied: Scoundrel, did you not vote for the death of the king? Lepelletier replied: That is true, because my confidence commanded me to do so.Instantly, the assassin pulled a saber, called a lighter, from under his coat and plunged it furiously into his left side, his lower abdomen; it created a wound four inches deep and four fingers wide. The assassin escaped with the help of his accomplices. Lepeletier still had the gentleness to forgive him, to pray that no further action would be taken; his strength allowed him to make his declaration to the public officer, and to sign it. He was placed in the hands of the surgeons who took him to his brother, at Place Vendôme. I went there immediately, led by my tender friendship, and my reverence for the virtues which he practiced without ostentation: I found him on his death bed, unconscious. When he showed me his wound, he uttered only these two words: I'm cold. He died this morning, at half past one, saying that he was happy to shed his blood for the homeland; that he hoped that the sacrifice of his life would consolidate Liberty; that he died satisfied with having fulfilled his oaths.

This was the first time a Convention deputy had gotten murdered, and it naturally caused strong reactions. Already the same session when Maure had announced Lepeletier’s death, the Convention ordered the following:

There are grounds for indictment against Pâris, former king's guard, accused of the assassination of the person of Michel Lepelletier, one of the representatives of the French people, committed yesterday.

[The Convention] instructs the Provisional Executive Council to prosecute and punish the culprit and his accomplices by the most prompt measures, and to without delay hand over to its committee of decrees the copies of the minutes from the justice of the peace and the other acts containing information relating to this attack.

The Decrees and Legislation Committees will present, in tomorrow's session, the drafting of the indictment.

An address will be written to the French people, which will be sent to the 84 departments and the armies, by extraordinary couriers, to inform them of the crime against the Nation which has just been committed against the person of Michel Lepelletier, of the measures that the National Convention has taken for the punishment for this attack, to invite the citizens to peace and tranquility, and the constituted authorities to the most exact surveillance.

The entire National Convention will attend the funeral of Michel Lepelletier, assassinated for having voted for the death of the tyrant.

The honors of the French Pantheon are awarded to Michel Lepelletier, and his body will be placed there.

The president is responsible for writing, on behalf of the National Convention, to the department of Yonne, and to the family of Lepelletier.

The next day, January 22, further instructions were given regarding Lepeletier’s funeral:

On Thursday January 24, Year 2 of the Republic, at eight o'clock in the morning, will be celebrated, at the expense of the Nation, the funeral of Michel Lepeletier, deputy of the department of Yonne to the National Convention.

The National Convention will attend the funeral of Michel Lepeletier in its entirety. The executive council, the administrative and judicial bodies will attend it as well.

The executive council and the department of Paris will consult with the Committee of Public Instruction regarding the details of the funeral ceremony.

The last words spoken by Michel Lepeletier will be engraved on his tomb, they are as follows: “I am happy to shed my blood for the homeland; I hope that it will serve to consolidate Liberty and Equality; and to make their enemies recognized.”

In number 27 (January 27 1793) of Gazette Nationale ou Le Moniteur Universel, the following long description was given over Lepeletier’s funeral, held three days earlier:

The funeral of Lepeletier Saint-Fargeau was celebrated on Thursday 24 with all the splendor that the severity of the weather and the season allowed, but with such a crowd that it could have been the most beautiful day of the year. At ten o'clock in the morning his deathbed was placed on the pedestal where the equestrian statue of Louis XVI previously stood, on Place Vendôme, today Place des Piques. One went up to the pedestal by two staircases, on the banisters of which were antique candelabras. The body was lying on the bed with the bloody sheets and the sword with which he had been struck. He was naked to the waist, and his large and deep wound could be seen exposed. These were the mournful and most endearing part of this great spectacle. All that was missing was the author of the crime, chained, and beginning his torture by witnessing the sight of the triumph of Saint-Fargeau.

As soon as the National Convention and all the bodies that were to form courage were assembled in the square, mournful music was played. It was, like almost all those which has embellished our revolutionary festivals, the composition of citizen Gossec. The Convention was ranged around the pedestal. The citizen in charge of the ceremonies presented the President of the Convention with a wreath of oak and flowers; then the president, preceded by the ushers of the Convention and the national music, went around the monument, and went up to the pedestal to place the civic crown on Lepeletier's head: during this time, a federate gave a speech; the president dismounted, the procession set out in the following order: A detachment of cavalry preceded by trumpets with fourdincs. Sappers. Cannoneers without cannons. Detachment of veiled drummers. Declaration of the rights of man carried by citizens. Volunteers of the six legions, and 24 flags. Drum detachment. A banner on which was written the decree of the Convention which ordered the transport of Lepeletier's body to the Pantheon. Students of the homeland. Police commissioners. The conciliation office. Justices of the peace. Section presidents and commissioners. The commercial court. The provisional criminal court. The department’s fix courts. The electorate. The provisional criminal court. The department's criminal courts fix. The municipality of Paris. The districts of Saint-Denis and the village of L’Égalité. The Department. Drum detachment. The seal of the 84, worn by Federates. The provisional executive council. National Convention Guard Detachment. The court of cassation. Figure of Liberty carried by citizens. The bloody clothes worn at the end of a national pike, deputies marching in two columns. In the middle of the deputies was a banner where Lepeletier's last words were written: "I am happy to shed my blood for my homeland, I hope that it will serve to consolidate Liberty and Equality, and to make their enemies known.”

The body carried by citizens, as it was exhibited on the Place des Piques. Around the body, gunners, sabers in hand, accompanied by an equal number of Veterans. Music from the National Guard, who performed funeral tunes during the march. Family of the dead. Group of mothers with children. Detachment of the Convention Guard. Veiled drums. Volunteers of the six legions and 24 flags. Veiled drums. Volunteers of the six legions and 24 flags. Veiled drums. Volunteers of the six legions and 24 flags. Veiled drums. Armed federations. Popular societies. Cavalry and trumpets with fourdines. On each side, citizens, armed with pikes, formed a barrier and supported the columns. These citizens held their pikes horizontally, at hip height, from hand to hand. The procession left in this order from the Place des Piques, and passed through the streets St-Honoré, du Roule, the Pont-Neuf, the streets Thionville (former Dauphine), Fossés Saint-Germain, Liberté (former Fossés M. le Prince), Place Saint-Michel and Rue d'Enfer, Saint-Thomas, Saint-Jacques and Place du Panthéon. It stopped front of the meeting room of the Friends of Liberty and Equality; opposite the Oratory, on the Pont-Neuf, opposite the Samaritaine; in front of the meeting room of the Friends of the Rights of Man; at the intersection of Rue de la Liberté; Place Saint-Michel and the Pantheon. Arriving at the Pantheon, the body was placed on the platform prepared for it. The National Convention lined up around it; the band, placed in the rostrum, performed a superb religious choir; Lepeletier's brother then gave a speech, in which he announced that his brother had left a work, almost completed, on national education, which will soon be made public; he ended with these words: I vote, like my brother, for the death of tyrants. The representatives of the people, brought closer to the body, promised each other union, and swore on the salvation of the homeland. A big chorus to Liberty ended the ceremony.

According to Michel Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau, 1760-1793 (1913), civic festivals in honor of Lepeletier were celebrated in all sections of Paris, as well as the towns of Arras, Toulouse, Chaumont, Valenciennes, Dijon, Abbeville and Huningue. Lepeletier’s body did however only get to rest in the Panthéon for a little more than a year, as on February 15 1795, the Convention ordered it exhumed, at the same time as that of Marat. It was instead buried in the park surrounding Château de Ménilmontant, the properly of which the ancestor Lepeletier de Souzy had purchased in the 17th century and that still remained in the family.

One day after the funeral, January 25, Lepeletier’s only child, the ten and a half year old Susanne, who had already lost her mother ten years before the murder of her father, was brought before the Convention by her step-mother and two paternal uncles Amédée and Félix. It was Félix who had held a speech during the funeral and he would continue to work for his seven years older brother’s memory afterwards too, offering a bust of him to the Convention on February 21 1793, (on the proposal of David, it was placed next to the one of Brutus), reading his posthumous work on public education to the Jacobins on July 19 1793, and even writing a whole biography over his life in 1794 (Vie de Michel Lepeletier, représentant du peuple français, assassiné à Paris le 20 janvier 1793 : faite et présentée a la Société des Jacobins).

The president announces that the widow of Michel Lepelletier, his two brothers and his daughter, request to be admitted to the bar, to testify to the Convention their recognition of the honors that they have decreed in memory of their relative. It is decreed that they will be admitted immediately.

One of Michel Lepeletier’s brothers: Citizens, allow me to introduce my niece, the daughter of Michel Lepelletier; she comes to offer you and the French people her recognition of the eternity of glory to which you have dedicated her father... He takes the young citoyenne Lepelletier in his arms, and makes her look at the president of the Convention... My niece, this is now your father... Then, addressing the members of the Convention, and the citizens present at the session: People, here is your child... Lepelletier pronounces these last words in an altered voice: silence reigns throughout the room, with exception for a couple of sobs.

The President: Citizens, the martyr of Liberty has received the just tribute of tears owed to him by the National Convention, and the just honor that his cold skin has received invites us to imitate his example and to avenge his death. But the name of Lepelletier, immortal from now on, will be dear to the French Nation. The National Convention, which needs to be consoled, finds relief to its pain in expressing to his family the just regrets of its members and the recognition of the great Nation of which it is the organ. The Nation will undoubtedly ratify the adoption of Michel Lepelletier's daughter that is currently being carried out by the National Convention.

Barère: The emotion that the sight of Michel Lepeletier's only daughter has just communicated to your souls must not be infertile for the homeland. Susanne Lepelletier lost her father; she must find now find one in the French people. Its representatives must consecrate this moment of all-too-just felicity to a law that can bring happiness to several citizens and hope to several families. The errors of nature, the illusions of paternity, the stability of morals, have long demanded this beautiful institution of the Romans. What more touching time could present itself at the National Convention to pass into French legislation the principle of adoption, than that when the last crimes of expiring tyranny deprived the homeland of one of its ardent defenders and Susanne Lepelletier of a dear father! Let the National Convention therefore give today the first example of adoption by decreeing it for the only offspring of Lepelletier; let it instruct the Legislation Committee to immediately present the bill on this interesting subject. I ask that the homeland adopt through your organ Susanne Lepelletier, daughter of Michel Lepelletier, who died for his country; that it decrees that adoption will be part of French legislation, and instructs its Legislation Committee to immediately present the draft decree on adoption.

This proposal is unanimously approved.

Susanne being adopted by the state would however lead to a fierce debate when, in 1797, this ”daughter of the nation” wished to marry a foreigner. For this affair, see the article Adopted Daughter of the French People: Suzanne Lepeletier and Her Father, the National Assembly (1999)

Right after Barère’s intervention, David took to the rostrum:

David: Still filled with the pain that we felt, while attending the funeral procession with which we honored the inanimate remains of our colleagues, I ask that a marble monument be made, which transmits to posterity the figure of Lepelletier , as you clearly saw, when it was brought to the Pantheon. I ask that this work be put into competition.

Saint-André: I ask that this figure be placed on the pedestal which is in the middle of Place Vendôme... (A few murmurs arise)

Jullien: I ask that the Convention adopt in advance, in the name of the homeland, the children of the defenders of Liberty, who, for similar reasons, could be immolated in the vengeance of the royalists.

All these proposals are referred to the Legislation and Public Instruction Committees.

On Maure's proposal, the Assembly orders the printing of the speeches delivered yesterday at the Panthéon, by one of Michel Lepelletier's brothers, Barère and Vergniaux.

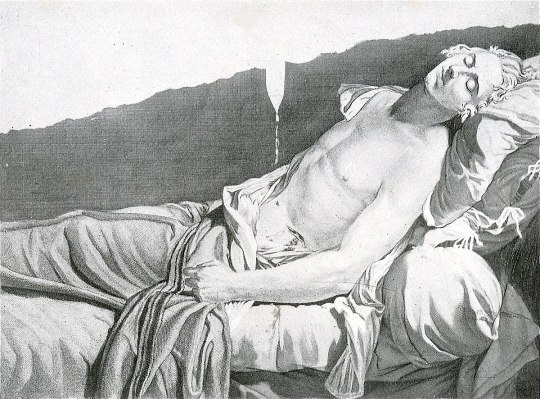

If it would appear David never got to make a marble monument of Lepeletier, on March 28 1793, he could nevertheless present the following painting of his to the Convention, which isn’t just a little similar to his La Mort de Marat.

(This image is an engraving of the actual painting, which has gone missing)

After Marat on July 13 1793 (on the very same day the plan for public education Lepeletier had been working on was read to the Convention by Robespierre) became the second assassinated Convention deputy, we find several engravings etc, depicting the two ”martyrs of liberty” side by side.

In the following months, even more people would be join the two, such as Joseph Chalier, a lyonnais politician executed on July 17 1794 and Joseph Bara, a fourteen year old republican drummer boy killed in the Vendée by the pro-Monarchist forces.

Lepeletier’s murderer, 27 year old Philippe Nicolas Marie de Pâris, a man who the minister of justice described as "former king's guard, height five pieds, five pouces, barbe bleue, and black hair; swarthy complexion, fine teeth, dressed in a gray cloak, green lapels and a round hat” on January 21, went into hiding right after his deed. In spite of his description being published in the papers and a considerable sum of money being promised to whoever caught him, Pâris managed to flee Paris and settled for a country house of an acquaintance near Bourget. He there ran into a cousin of one of the owners. When Pâris asked for food and a bed, he was refused and instead disappeared into the night again. In the evening of January 28 he arrived in Forges-les-Eaux and stopped at an inn, where he came under suspicion once he started cutting his bread with a dagger after which he locked himself into his room. The following morning he woke up with a start as five municipal gendarmes came bursting into his room and told him to come with them. Pâris responded that he would, but in the next second he had picked up his hidden pistol, placed it into his mouth, and pulled the trigger. Searching the dead body, the gendarmes found Pâris’ baptism record (dated November 12 1765) and dismissal from the king's guard (dated June 1 1792), on the latter of which had been written the following:

My certificate of honor. Do not trouble anyone. No one was my accomplice in the fortunate death of the scoundrel de Saint-Fargeau. Had I not run into him, I would have carried out a more beautiful action: I would have purged France of the patricide, regicide and parricide d’Orléans. The French are cowards to whom I say:

Peuple dont les forfaits jettent partout l'effroi, Avec calme et plaisir j'abandonne la vie.

Ce n'est que par la mort qu'on peut fuir l'infamie Qu'imprime sur nos fronts le sang de notre roi.

Signed by Paris the older, guard of the king, assassinated by the French.

Learning about what had happened, the Convention tasked Tallien and Legrand with going to … and making sure the dead man really was Pânis. Having come to the conclusion that this was indeed the case, the deputies briefly discussed whether the body ought to be brought back to Paris, but it was decided it would be better if it was just buried "with ignominy.” It was therefore instead just taken into the nearby forest in a wheelbarrow and thrown into a six feet deep hole.

Finally, here are some other revolutionaries simping for honoring Lepeletier’s memory just because I can:

…a tragic event took place the day before the execution [of the king]. Pelletier, one of the most patriotic deputies, and who had voted for death, was assassinated. A king's guard made a wound three fingers wide with a saber: he died this morning. You must judge the effect that such a crime has had on the friends of liberty. Pelletier had an income of six hundred thousand livres; he had been président à mortier in the Parliament of Paris; he was barely thirty years old; to many talents, he added the most estimable of virtues. He died happy, he took to his grave the idea, consoling for a patriot, that his death would serve the public good. Here then is one of these beings whom the infamous cabal who, in the Convention, wanted to save Louis and bring back slavery, designated to the departments as a Maratist, a factious, a disorganizer... But the reign of these political rascals is finished. You will see the measures that the Assembly took both to avenge the national majesty and to pay homage to a generous martyr of liberty.

Philippe Lebas in a letter to his father, January 21 1793

Ah! if it is true that man does not die entirely and that the noblest part of himself survives beyond the grave and is still interested in the things of life, come then, dear and sacred shadow, sometimes to hover above the Senate of the nation that you adorned with your virtues; come and contemplate your work, come and see your united brothers contributing to the happiness of the homeland, to the happiness of humanity.

Marat in number 105 (January 23 1793) of Journal de la République Française

O Lepeletier! Your death will serve the Republic: I envy your death. You ask for the honors of the Pantheon for him, but he has already collected the prize of martyrdom of Liberty. The way to honor his memory is to swear that we will not leave each other without having given a constitution to the Republic.

Danton at the Convention, January 21 1793

O Le Peletier, tu étais digne de mourir pour la patrie sous les coups de ses assassins ! Ombre chère et sacrée, reçois nos vœux et nos serments ! Généreux citoyen, incorruptible ami de la vérité, nous jurons par tes vertus, nous jurons par ton trépas funeste et glorieux de défendre contre toi la sainte cause dont tu fus l'apôtre; nous jurons une guerre éternelle au crime dont tu fus l'éternel ennemi, à la tyrannie et à la trahison, dont tu fut la victime. Nous envions ta mort et nous saurons imiter ta vie. Elles resteront à jamais gravées dans nos cœurs, ces dernières paroles où lu nous montrais ton âme tout entière; ”Que ma mort, disais tu, sera utile à la patrie, qu'elle serve à faire connaître les vrais et les faux amis de la liberté, et je meurs content.

Robespierre at the Jacobins, January 23

Wednesday 23 [sic] — We went to Madame Boyer’s to see the procession. I saw the poor Saint-Fargeau. We all burst into tears when the body passed by, we threw a wreath on it. After the ceremony, we returned to my house. Ricord and Forestier had arrived. I was unable to stop my tears for some time. F(réron), La P(oype), Po, R(obert) and others came to dinner. The dinner was quite fun and cheerful. Afterwards they went to the Jacobins, Maman and I stayed by the fire and, our imaginations struck by what we had seen, we talked about it for a while. She wanted to leave, I felt that I could not be alone and bear the horrible thoughts that were going to besiege me. I ran to D(anton’s). He was moved to see me still pale and defeated. We drank tea, I supped there.

Lucile Desmoulins in her diary, January 24 1793

…Pelletier's funeral took place this Thursday as I informed you in my last letter (this letter has gone missing). The procession was immense; it seemed that the population of Paris had doubled, to honor the memory of this virtuous citizen. The mourning of the soul was painted on all the faces: it was especially noticed that the people were extremely affected, which proves that they keenly felt the price of the friend they had lost. Arriving at the Pantheon, Lepelletier's body was placed on the platform prepared for it; his brother delivered a speech which was applauded with tears; Barère succeeded him. Then the members of the Convention, crowding around the body of their colleague, promised union among themselves, and took an oath to save the country. God grant that we have not sworn in vain, that we finally know the full extent of our duties, and that we only occupy ourselves with fulfilling them! In yesterday's session, Pelletier's daughter, aged eight [sic], was presented to the National Convention, which immediately adopted her as a child of the homeland.

Georges Couthon in a letter written January 26 1793

How could I be so base as to abandon myself to criminal connections, I who, in the world, have never had more than one close friend since the age of six? (he gestures towards David's painting). Here he is! Michel Lepeletier, oh you from whom I have never parted, you whose virtue was my model, you who like me was the target of parliamentary hatred, happy martyr! I envy your glory. I, like you, will rush for my country in the face of liberticidal daggers; but did I have to be assassinated by the dagger of a republican!

Hérault de Sechelles at the Convention, December 29 1793

For a collection of Lepeletier’s works, see Oeuvres de Michel Lepeletier Saint-Fargeau, député aux assemblées constituante et conventionnelle, assassiné le 20 janvier 1793, par Paris, garde du roi (1826)

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

The slap that launched a thousand gifs? #ifonlyihadtheskillz #animatedcollage?

When you get publicly slapped by 4 surrealist poets because you insulted a guy's historical crush

(translation and context under the cut)

Gallantly Defending Robespierre’s Honour

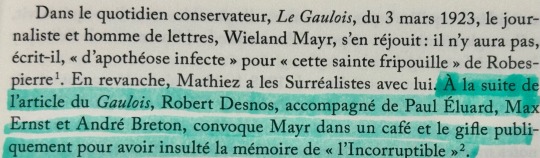

In the conservative daily paper, Le Gaulois, on March 3, 1923, the journalist and man of letters, Wieland Mayr, expressed his pleasure: there would not be, he wrote, a "vile apotheosis" for "that holy scoundrel" Robespierre. On the other hand, Mathiez had the Surrealists with him. Following the article in Le Gaulois, Robert Desnos (1), accompanied by Paul Éluard (2), Max Ernst (3), and André Breton (4), summoned Mayr in a café and publicly slapped him for insulting the memory of "the Incorruptible."

Why did Mayr get Slapped?

In short: studying history in the 1920s was a messy business, especially when it came to the French Revolution….

To explain why Mayr ended up getting slapped, please allow me to briefly dive into the French Revolution's historiography during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Keep in mind, that this is a grossly oversimplified version.

Before 1848, it was pretty standard for French republicans to proudly see themselves as inheritors of Robespierre’s legacy. (If you’ve ever wondered why in Les Misérables, Enjolras’ character is very much channeling Robespierre and Saint-Just, here’s your answer!) However, things start to change with the Second Republic.

In 1847, Jules Michelet brought back the negative portrayal of Robespierre as a tyrannical "priest" and leader of a new cult. This narrative helped fuel an increasing dislike for Robespierre, with radicals like Auguste Blanqui arguing that the real revolutionaries were the atheistic Hébertists, not the Robespierrists.

Jump to the Third Republic, and the negative sentiment towards Robespierre was only getting stronger, driven by voices like Hippolyte Taine, who painted Robespierre as a mediocre figure, overwhelmed by his role. This trend was politically motivated, aiming to reshape the Revolution's legacy to align with the Third Republic's secular values. Obviously, Robespierre, the "fanatic pontiff" of the Supreme Being, didn’t quite fit this revised narrative and was made out to be the villain. Alphonse Aulard (a historian willing to stretch the truth to make his point) continued pushing Danton as the face of secular republicanism. Albert Mathiez, one of Aulard’s students, was not having any of it and strongly disagreed with his mentor’s approach.

The general disdain for Robespierre began to shift after World War I. One reason was that people could better appreciate the actions of the Revolutionary Government after experiencing the repression during the war themselves. Albert Mathiez and his colleagues were actively working to change Robespierre's tarnished image. With tensions high, it's no wonder Mayr ended up being publicly slapped by a bunch of poets who were defending the Incorruptible's honour!

Notes

Robert Desnos (1900-1945) was a French poet deeply associated with the Surrealist movement, known for his revolutionary contributions to both poetry and resistance during World War II.

Paul Éluard (1895-1952) was a French poet and one of the founding members of the Surrealist movement, celebrated for his lyrical and passionate writings on love and liberty.

Max Ernst (1891-1976) was a German painter, sculptor, graphic artist, and poet, a pioneering figure in the Dada and Surrealist movements known for his inventive use of collage and exploration of the unconscious.

André Breton (1896-1966) was a French writer, poet, and anti-fascist, best known as the principal founder and leading theorist of Surrealism, promoting the liberation of the human mind.

Source: The text in the picture comes from Robespierre and the Social Republic by Albert Mathiez

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another new portrait. But no details?

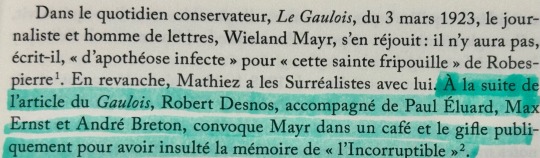

Portrait de Marat, Anonyme.

Trouvé dans la collection de la Musée Carnavalet.

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maximilian Robespierre, Deputy. ‘Incorruptible’. Mountain’s Highly Confidential WhatsApp Group

Wow. What a week, guys! Did you see my speech on virtue and terror the other day. Four pages in the Moniteur, three in the Revolutions de Paris and a special pullout in the Jacobin Club bulletin with a questionnaire ‘how virtuous are you?’ and a special souvenir print. By David. Of me!

Danton: No one reads the JCC anymore since the nutters took over

Camille: I keep a pile by the privy. Looroll’s so expensive these days!

Shade of Jean-Paul: You stole all my best lines. Even your nickname is mine

All: WTF! How did you get on here?

Shade: I am everywhere. I am the eye of the people!

Bertrand: Quick, everyone. Block him! Now!

Shade: you seem to forget, I am the moderator. And I have the password

Bertrand: Moderate! You! Moderate? Ha!

Shade: and you call yourself a writer?! Fucking windvane!

Max: damn! Just ignore him guys. Now as I was saying….

Louis-Antoine: but he can still be useful. You know, the people kind of worship him now

Max: but I want them to worship me! Why won’t they worship me?

All: sniggering

Camille: because you’re not dead?

George: because you’re killing them?

Max: that’s not fair

Camille: would you prefer it in Latin?

Max: et tu Camillus?

Bertrand: (clears throat) c’mon public safety people, we’re getting off the point. So Max, I got your speech translated into English. Found an excellent expat with impeccable credentials, Ms Helen Maria Williams. We’re going to print it up on English type and smuggle it over the Channel to freak them all out and show what a nice guy you really are.

Max: merci BB

Shade: (interrupting) I denounce…

All: blocked!

Shade: … you can all take your worthless block and shove it up your collective arse. I denounce Barere and Ms Williams

Camille: For god’s sake Jean-Paul, get a grip

George: I do not know this individual

Max: me either

Bertrand: is that even proper grammar?

Max: it is now!

George: right, I’m bored. Got to see a man about a property

Camille: can I come?

George: no, no, and always, no! And yes my friends, I shall in future be terrorising my new wife by asking her, ‘are you feeling virtuous tonight?’ You should try it Max, might loosen you up a bit

Camille: he should be so lucky! I feel a song coming on. Red, the sound of ages past, blue the colour of my hair, white the…

All: no!

TBC

#Jean-Paul Marat #Maximilien Robespierre #Bertrand Barere #Camille Desmoulins #Georges Danton #Louis-Antoine Saint-Just #whatsapp satire #French Revolution #Max just needed a big slap #and a hug from time to time #The Mountain #Committee of Public Safety #Jacobin japes

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fascinating. Didn’t read this in any of the 1001 biographies devoted to Max! Guessing no one ever defended Jean-Paul’s honour this way though several did go to prison for reprinting his work…

When you get publicly slapped by 4 surrealist poets because you insulted a guy's historical crush

(translation and context under the cut)

Gallantly Defending Robespierre’s Honour

In the conservative daily paper, Le Gaulois, on March 3, 1923, the journalist and man of letters, Wieland Mayr, expressed his pleasure: there would not be, he wrote, a "vile apotheosis" for "that holy scoundrel" Robespierre. On the other hand, Mathiez had the Surrealists with him. Following the article in Le Gaulois, Robert Desnos (1), accompanied by Paul Éluard (2), Max Ernst (3), and André Breton (4), summoned Mayr in a café and publicly slapped him for insulting the memory of "the Incorruptible."

Why did Mayr get Slapped?

In short: studying history in the 1920s was a messy business, especially when it came to the French Revolution….

To explain why Mayr ended up getting slapped, please allow me to briefly dive into the French Revolution's historiography during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Keep in mind, that this is a grossly oversimplified version.

Before 1848, it was pretty standard for French republicans to proudly see themselves as inheritors of Robespierre’s legacy. (If you’ve ever wondered why in Les Misérables, Enjolras’ character is very much channeling Robespierre and Saint-Just, here’s your answer!) However, things start to change with the Second Republic.

In 1847, Jules Michelet brought back the negative portrayal of Robespierre as a tyrannical "priest" and leader of a new cult. This narrative helped fuel an increasing dislike for Robespierre, with radicals like Auguste Blanqui arguing that the real revolutionaries were the atheistic Hébertists, not the Robespierrists.

Jump to the Third Republic, and the negative sentiment towards Robespierre was only getting stronger, driven by voices like Hippolyte Taine, who painted Robespierre as a mediocre figure, overwhelmed by his role. This trend was politically motivated, aiming to reshape the Revolution's legacy to align with the Third Republic's secular values. Obviously, Robespierre, the "fanatic pontiff" of the Supreme Being, didn’t quite fit this revised narrative and was made out to be the villain. Alphonse Aulard (a historian willing to stretch the truth to make his point) continued pushing Danton as the face of secular republicanism. Albert Mathiez, one of Aulard’s students, was not having any of it and strongly disagreed with his mentor’s approach.

The general disdain for Robespierre began to shift after World War I. One reason was that people could better appreciate the actions of the Revolutionary Government after experiencing the repression during the war themselves. Albert Mathiez and his colleagues were actively working to change Robespierre's tarnished image. With tensions high, it's no wonder Mayr ended up being publicly slapped by a bunch of poets who were defending the Incorruptible's honour!

Notes

Robert Desnos (1900-1945) was a French poet deeply associated with the Surrealist movement, known for his revolutionary contributions to both poetry and resistance during World War II.

Paul Éluard (1895-1952) was a French poet and one of the founding members of the Surrealist movement, celebrated for his lyrical and passionate writings on love and liberty.

Max Ernst (1891-1976) was a German painter, sculptor, graphic artist, and poet, a pioneering figure in the Dada and Surrealist movements known for his inventive use of collage and exploration of the unconscious.

André Breton (1896-1966) was a French writer, poet, and anti-fascist, best known as the principal founder and leading theorist of Surrealism, promoting the liberation of the human mind.

Source: The text in the picture comes from Robespierre and the Social Republic by Albert Mathiez

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

This could be a major find? Never seen before

Was browsing for frev relics and came across an interesting Marat painting claiming to be from 1791 ! I'm really not sure about the accuracy of the dating but nonetheless, it's without a doubt a painting of Jean-Paul !

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apologies. You have to sign up for a free account

“My review of Ridley Scott’s Napoleon has come out in The New York Review of Books. It’s always hard for me to watch films on my area of expertise, and not grimace at the inaccuracies. Obviously, creative artists should be free to take liberties with the historical record, but they should have good reasons for doing so. I didn’t see any good reason to portray Napoleon Bonaparte as a petulant, whiny, lovesick boor with a perpetually confused expression on his face. And Scott tries to have things both ways, On the one hand, he claims the right to alter the history (“When I have issues with historians, I ask: ‘Excuse me, mate, were you there? No? Well, shut the fuck up then.”) On the other, he insists he is offering an actual historical judgment. The actual life of Napoleon Bonaparte would have made for far more gripping drama than Scott’s work, and I conclude the review by offering a comparison to a much earlier film that took the man’s life much more seriously: Abel Gance’s 1927 Napoleon.”

#napoleon#film#ridley scott#review#why distort history when the real deal is so much more compelling?!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Great compilation

Abbe Proyart talking shit about his former students compilation

(With the exception of student Robespierre, who he spoke so much shit about you can make a whole post only about it)

Camille Desmoulins, Robespierre's warmest friend and most ardent advocate, was the son of a Lieutenant-General of the Bailliage of Guise in Picardy. Appointed as scholar by the Chapter of Laon at the College of Louis-le-Grand, he completed his studies, if not with distinction, at least with some success. Although from then on he wrote his scholastic compositions well, he spoke very heavily and stammered in speech. He had an ugly and repulsive exterior, a black complexion, and something sinister about his eyes. He had nevertheless announced in his early youth the double emulation of work and virtue; but, disturbed in his higher classes by vicious comrades, he abjured piety, and soon showed himself a more bitter enemy than even those who had driven him away from it. From then on, a muddled spirit, surly and eloquent, he made himself odious to all his fellow students, and no longer had a single friend among them. We then saw him, son of nature and ungrateful disciple, displaying all the feelings of a bad heart. He made his debut at the bar with a plea against his father, whom he pretended to oblige to furnish him in Paris with an interview which exceeded his faculties. He never forgave his Masters for the efforts they had made to correct his budding vices. In the time of the Revolution, he was still cruelly resentful of one of them, on the occasion of a close encounter fifteen years earlier. “I will never forgive him, he said, for having told me one day that I would mount the scaffold.” However, if the horoscope wasn’t flattering, it was nonetheless verified. We shall see later how, still believing himself to be the friend of Robespierre, he was rewarded for his revolutionary labors by his friend.

La vie et les crimes de Robespierre, surnommé Le Tyran, depuis sa naissamce jusqu’à sa mort(1795) by Le Blond de Neuvéglise (abbé Proyart), page 93

Fréron, in his youth, showed a gloomy and defimulated character, especially near his masters. He announced rather few talents, and no will to cultivate them; he was also cited as a rare example when speaking of laziness and indolence. He was one of those indifferent to religion to whom justice is done by always suspecting their morals. Coming out from the college, he walked his impoverished existence for a long time on the pavement of the Capital, a burden equally incumbent upon both his family and Abbé Royou, his protector and brother of the estimable Madame Fréron.

Ibid, page 90

Duport-du Tertre, born in Paris, of a not very wealthy family, after having done fairly good studies at the College of Louis-le-Grand, became a lawyer, and got a certain reputation, above all, for probity and justice. He was of a gentle and honest character, although a little cold. He loved work and solitude. His conduct at the College had always been good; but of a wisdom more philosophical than religious. He was not born to be a scoundrel, and it cannot be said that he was; but he had not enough religion to cling to, in a slippery step, to the great principles which it enshrines, and he abandoned them. As Constitutional Minister, he tried to serve the Constitution and the King; and, without doing anything useful for the King or for the Constitution, he could not escape the guillotine. It had been less by any particular affection than at the request of his old college comrades whom Duport-du Tertre had endeavored to make known to Robespierre, whom he knew little of himself. Robespierre, in return for the disinterested zeal he had shown him on his arrival in Paris, worked harder than any other Jacobin to make him suspect and determine his execution.

Ibid, page 85-86

Le Brun, known in his youth under the name of Abbé Tondu, was from Noyon. Provided by the Chapter of this City with a scholarship assigned to young clerics, he found himself a contemporary of Robespierre at the College of Louis-le-Grand. He had made less of a sensation than him in his humanities, but showed more talent in philosophy. He then bore an extraordinary depth of timidity, which he retained something of his whole life. He was one of those soft and easy characters who, having neither the boldness of crime nor the courage of virtue, become what circumstances and societies that surround them make them into. The Abbé Tondu, who liked neither his estate nor his name, left both at the same time, and called himself Le Brun, after his mother. Leaving the college, he obtained at the Observatory one of the Places paid by the King to young men who had a marked inclination for Mathematics. The bad companies having thrown him into licentiousness, he pledged himself to it. […] The tottering Minister tried in vain to rely on his old liaisons with Robespierre: Robespierre no longer knew as a friend the one who could also have been friend of a man whose pride had always revolted his own. Le Brun did not cause the death of the King; but, like Dumouriez, he had the cowardice to consent to it; and, like him, he truly became its accomplice, while doing nothing of all that he ought to have done to prevent it, or to provoke vengeance.

Ibid, page 87-88

Noël, born under the name Dumouchel to poor parents, had received, like Robespierre, the gratuitous education of the poor. Student first at the College des Grassins, then at that of Louis-le-Grand; after rather brilliant successes in the distribution of the University Prizes, he was made quarter master, and then professor, at the College of Louis-le-Grand. This sudden passage, from extreme poverty to the last term of ambition among the young masters of the university, turned his head. He had little religion, he became impious. At the beginning of the Revolution, his sentiments, expressed in a journal of which he had made himself the editor, earned him a post as clerk in the war office, and then a secret mission on the part of the Jacobins in a foreign court. Friend of Camille Desmoulins, the latter had introduced him to Robespierre when he arrived in Paris for the Estates-General. Robespierre, although welcomed and celebrated by Noël, had conceived against him a fund of aversion, because he had obtained more constant successes than him at the University, and because Camille Desmoulins never ceased to exalt his talents. He spared him at first as a proponent useful to his views, then fell out with him, and then lost him as soon as he found the occasion.

Ibid, page 86-87

It is again from this school that came two low servants of these man-tigers, and the worthy adjudans of their villainy: the name of one was Sijas, that of the other Pilot. Sijas had obtained, from his college comrade Robespierre, the employment of confidence of overseeing the massacres of the guillotine in Paris; and Pilot, exercising the same Commission in Lyon, wrote to Robespierre that the pleasure of seeing the Lyonnais having their throats cut restored his health.

Louis XVI détrôné d’être Roi, ou tableau des causes de la Révolution française et de l’ébranlement de tous les trônes (1803) by Abbé Proyart, cited in Le collège Louis-le-Grand, séminaire de la Révolution (1913) by H. Monin.

And some of his fellow teachers too…

None of his masters contributed so much to the growth of the republican virus fermenting in his (Robespierre’s) soul than his Professor of Rhetoric. An enthusiastic admirer of the heroes of ancient Rome, M. Hérivaux, nicknamed The Roman by his students, thought that Robespierre’s personality had a strong Roman physiognomy. He praised him, cajoled him unceasingly, sometimes even congratulated him very seriously on this precious similarity. Robespierre, no less seriously, favored compliments, and was grateful to bear the soul of a Roman, be it the atrocious soul of a parricidal Brutus, or that of a conspiratorial Catiline.

La vie et les crimes de Robespierre… (1795) page 46-47

One day, however, a prefect, suddenly opening a door, finds him (Robespierre) on the commode reading a very nasty pamphlet. Caught in flagrante delicto, Robespierre thought himself lost; and, forgetting his natural pride, falls at the feet of the Arbiter of his fate and comes down to the humblest supplications. The Master with whom he had to deal was neither inflexible nor fervent in Morale. He was a man who had been heard more than once to exclaim among the young people: "Long live liberty, my friends: far from us the hypocrisy.” It was the Abbé Audrein, who since deserved, by his apostasy, to become the collegue of Robespierre in the Assembly of Factious, where he still sits. With such a judge, the affair of the bad book was civilized without difficulty, and did not even come to the knowledge of the other Masters of the House.

Ibid, page 37-38

Dumouchel, son of a poor Peasant from Picardy, would not have found within his family any resource for his education: the Sanctuary and the charity of the Faithful paid all the expense. Scholar of the Community of Ste. Barbe, he entered the College of Louis-le-Grand in quality of a quarter master. He fortified himself to go and teach Rhetoric at Rhodez, from where he was called back to Paris to occupy a chair at the College de la Marche. The Abbé Royou, to whom he paid court, had employed him, for a time, for the drafting of certain unimportant articles of his journal, which he had no leisure to deal with himself. A fairly ritual appearance, a supple character, a lot of talk, a little literature, and many more ambitious pretensions had given Dumouchel a certain reputation among that swarm of deplorable subjects which filled the Colleges of Paris; and, by their votes, he found himself Rector of the University at the time of the holding of the Estates-General. Hiding his unbridled ambition and his irreligion under the mask of the most complete devotion to the respectable Archbishop of this Capital, he united the voices of the Clergy for the Deputation. Scarcely had the Hypocrite been in possession of the title he aspired to, than, abandoning the sacred interests which had been entrusted to him, he formed an alliance with Robespierre, whom he at first advocated, and of whom he was later advocated, so much so that the Jacobins of Paris, judging him worthy of the Episcopat, sent his name to the Club of the town of Nismes, with the injunction to make the subject known to the electors of the department, as the one who suited them and whom they should name. All the Catholic Electors, with the exception of two, having refused to cooperate in the crime of an intrusion by Eve that the Protestant Electors, less delicate, assembled, gave their votes to the one whom the Jacobins had designated for them; and Dumouchel, proclaimed Constitutionally Catholic Bishop that, by fifteen Electors only, of which thirteen were Protestants, said goodbye to his friend Robespierre, and went to install himself in the Episcopal Palace of Nismes, which soon, as we know, was defiled by the most scandalous Scenes.

Ibid, page 83-85

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

#FrenchRevolution #queries

I've got stuff to post, interesting nuggets from the archives, which will take a bit of time to arrange properly, and which readers might wish to pursue further.

In the meantime, I'd like to put some queries out there to see if the hivemind has come across these stories and can direct me back the sources which I seem to have misplaced. Since I'm new, I know it will take time to build followers especially if rarely posting, but still worth a shot, I figure.

1/ First query. Edict by #ParisMunicipality c.1790-92? to shoot all pets, with a time announced after which any dogs found roaming would be exterminated.

2/Second query. Calculation in newspaper for how many pigeons would need to be killed to feed the starving population, c.1790-91?

3/ Third query. Recorded instances of refusal to eat potatoes, even when starving, since it was considered as animal feed.

4/ Fourth query. #Archibald Hamilton Rowan, Irish revolutionary c.1790s. William Hickey (memoirs) suggests he was the leader of a lush gang of thugs called the #Mohawks, who terrorized London's nightlife for three years, from 1771-73, after being sent down from Cambridge for chucking his tutor in the Cam. What makes it even more curious, and matches Rowan's character, a romantic man of action (described as a giant Hercules) who later challenged the future Home Secretary (#Dundas, then Lord Advocate of Scotland) to a duel, amongst other things, is that he would frequently recant his shameful behaviour when sober and offer to satisfy offended honour as best as he could. I'd love some more detail on the Mohawks if there is any

Many thanks in advance for anyone who might have some leads on these. And, of course, if I eventually dig them out, I'll post them here too.

0 notes

Text

The importance of being earnest

"I hope I shall not offend you Cecily if I state quite frankly and openly that you are in every way the very personification of absolute perfection". #oscarwilde #alliteration.

This is such a perfect line

To be continued…

Just a placemarker for the moment. A tiny intervention. Mostly interested in the #FrenchRevolution and hope to post something soon on #Marat, #Wollstonecraft or other related topics of interest.

2 notes

·

View notes