Text

Artist Spotlight : Nobuto Suga

It will surprise no one that Studio AHEAD loves walking through the deep forests of Marin. So it was a delight to speak this month with Nobuto Suga, a Japanese-born woodworker who shares with us not only an appreciation for Northern California's forests, but a willingness to allow the natural world to influence and guide his creative work. To look at a Suga piece is to read, behind each block of wood, the tree that gave the piece its form and the landscape that gave home to the tree: "We are not separate from our natural world. Nor are we separate from each other." We were happy to speak of creative partnerships with those we cherish: in our case, Elena and Homan; with Suga and his partner Amy.

Studio AHEAD: Share with us some of your journey in arriving to California. Did you grow up here? What was your introduction to woodworking?

Nobuto Suga: I grew up in the countryside of Hiroshima, surrounded by forest and farmland. I started playing around with wood when I was sixteen. I remember one day my father brought some pieces of milled lumber home. The pieces came from trees that had been cut down on one of his landscaping sites. I was fascinated by the grain patterns in the wood and I wondered what form I could shape from the wood. I made a towel rack and some shelves, those were my first woodworking projects. They are still in my family home, and whenever I visit there, I see the living element of memory in those early pieces.

In 2000, I went to upstate New York to study ecology and gain a wider understanding of ecosystems. On a visit to the West Coast my eyes were opened by the majestic landscape of an old-growth forest. When I settled in San Francisco in 2014, I reconnected with the forests and woodworking. I have been deepening my appreciation ever since.

SA: Does the region where the tree grows affect how you work with it? Does a tree in Japan necessitate a different way of keeping its integrity than does a tree in California?

NS: Yes, absolutely. It does affect how I work. I had an opportunity to work on the edge of the coast recently under an old cypress canopy. I felt a direct connection with the surrounding elements—the wind and the rocky landscape. Connectivity to place is a very important part of my process when forming and laying out a vision and a direction. Without that connection, I can not make work. Relationship to place is extremely meaningful for me.

The most majestic tree I have ever encountered is at a Shinto shrine in Hiroshima. It’s wildly branching. The tree is covered with moss and lichen. It hosts so much life. It is a living historical artifact. Typically the trees around shrines are given the most respect in Japan. But a tree is a tree and deserves deep respect no matter where it grows.

SA: Tell us more about this respect. How does a designer go about respecting the material? Does this play into or get in the way of innovation, of using materials new ways?

NS: I’m keen on using urban salvaged and reclaimed wood to extend the life of the source elements. Understanding resources and bringing out the best characteristics of the material are very important to me. Working with resources from this perspective can help lessen our consumption flow which is excessive and problematic. It is important to build awareness and have respect for our natural environment that we depend on for life. We are not separate from our natural world. I’m fortunate to have access to urban salvaged wood and reclaimed materials in the Bay Area. I’m just one of many here who works respectfully and consciously with wood. I’m glad to be part of this community of woodworkers.

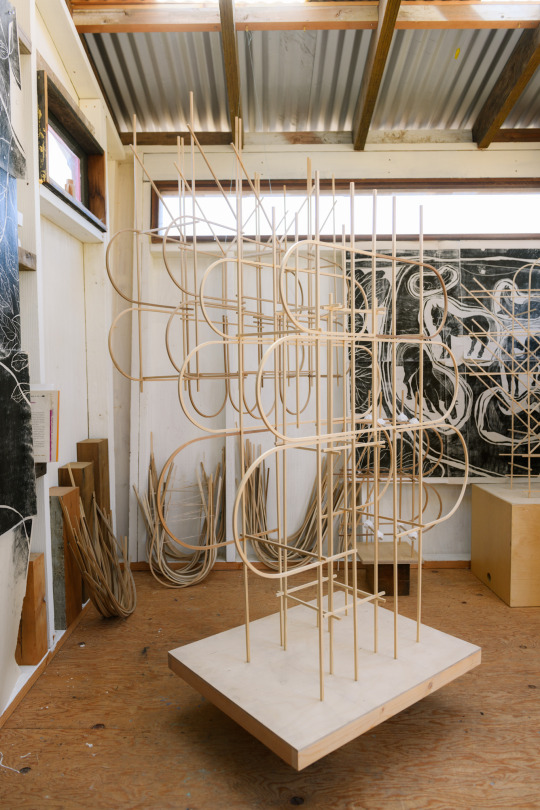

SA: You helped repair Sol LeWitt sculptures in New York. What ways do repair and creation intersect or diverge?

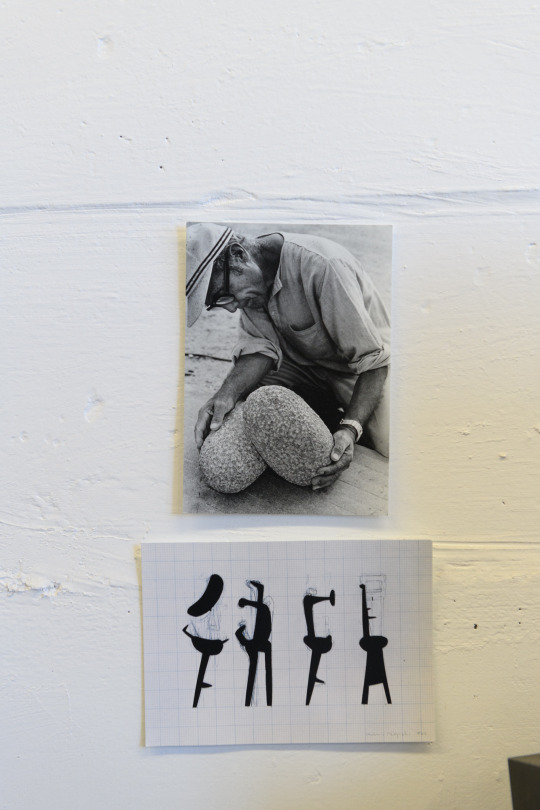

NS: My plan at that time was to attend a landscape architecture program, to explore physical interaction with space as a way of connecting with nature. But instead, I was fortunate to meet with a few Japanese artists who worked with Sol LeWitt for many decades. I participated in two executions of his Open Cube Structure, learning directly from a lead fabricator/artist, Kazuko Miyamoto. It was a very repetitive process, and it was pleasing to see the progress of structure and various visual effects that appeared in each step.

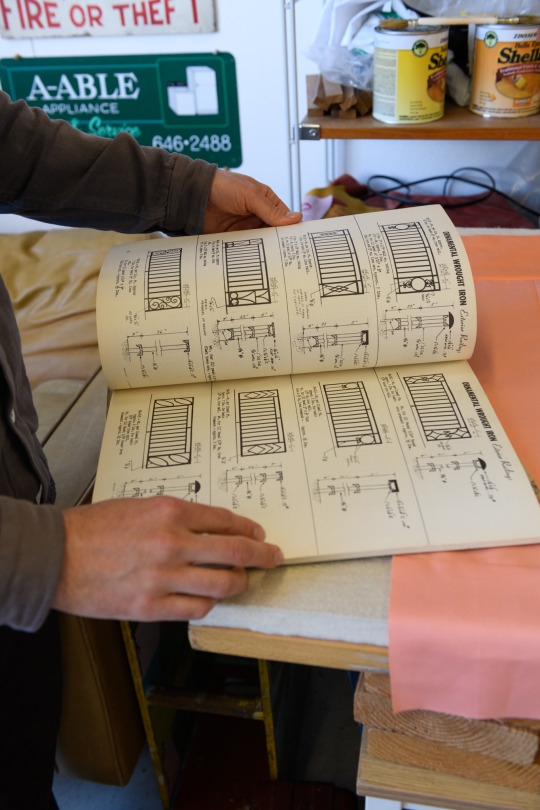

LeWitt’s sculptures are based on numbers, laying out a grid and a score, and the structural form emerges like a sound. The visual effects appear within the open cube from many different angles. I appreciate his vision, playfulness, endless curiosity, and openness to discoveries. LeWitt’s system of composition and application has a heavy impact on my practice.

Over time, I have developed an interest in kiwari, a traditional Japanese method of proportion or a co-relationship with each structural component. There is an underlying interconnectedness that I experience in nature, and when I make something, as I put pieces together I am always trying to respond to this feeling.

SA: Can you elaborate on this? Is this harmony of proportion what you are trying to achieve, or are you purposefully distorting these ideas of proportion to evoke certain emotions?

NS: Woodworking gives me new challenges all the time. The harmony of proportion is a starting point and a structuring principle of a concept and a process. I’m not distorting these ideas, I’m searching for the best way to accommodate the material and honor what it is offering.

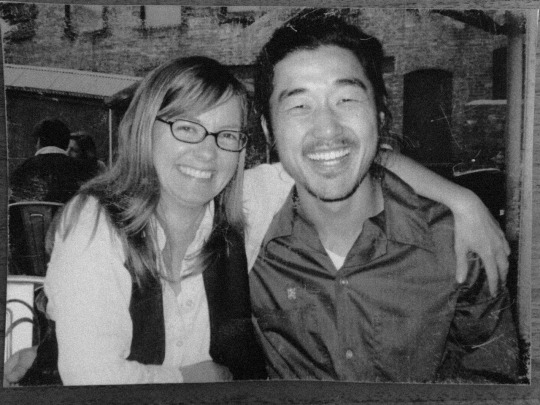

SA: Your partner, Amy, is your collaborator and you've built a home, studio and practice together. Tell us about how you work together. We [Elena and Homan] are creative partners and are grateful we have each other to move through creative life together. If one of us feels unbalanced, the other brings us back or carries the baton for a while.

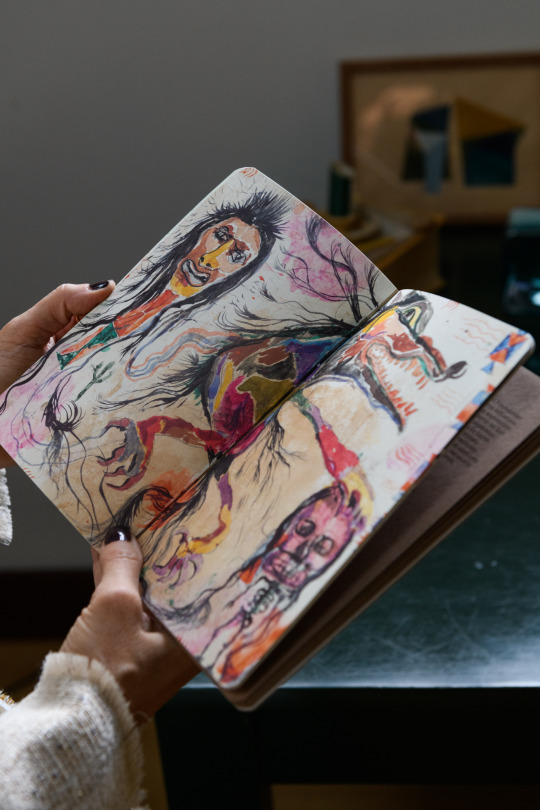

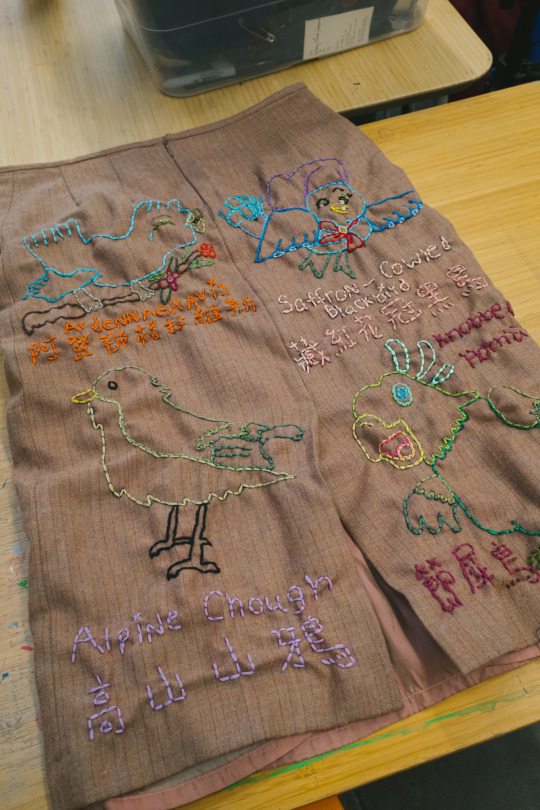

NS: Amy and I have been interacting and influencing each other with our creativity and sharing our appreciation for the last 15 years. She and I first met each other when we were both involved in the retrospective installation for Sol LeWitt at MASS MoCA in 2008. We had a spark and a similar appreciation of nature and have been together ever since. Our cultural backgrounds are different, but our attention to detail is the same. We’re both interested in the qualities of line and the negative space between things. And we both have a lot of respect for the untouched elements of a place or a material. We have been cultivating a shared language for the last fifteen years.

We tend to take turns supporting each other’s passions and projects. When I was pursuing ecological restoration, I assisted Amy’s art practice by helping with installation and gathering materials. Five years ago, Amy set up our family woodworking business, Suga Studio.

I enjoy and appreciate her vision, playfulness with elements, and I admire her ability to transform an indescribable emotion to visualized formations. Our practices blend with regular and creative existence in a way that gives us energy and flexibility. Pursuing the passion and our listening hearts is filling me with gratitude and compassion. Our next direction is making an even deeper connection with nature. It inspires us both to the core of our being.

Photos by Ekaterina Izmestieva

#studioahead#northern california#bayarea#studio ahead#artistspotlight#san francisco#california#interiordesign#art#nobuto suga#nobutosuga

0 notes

Text

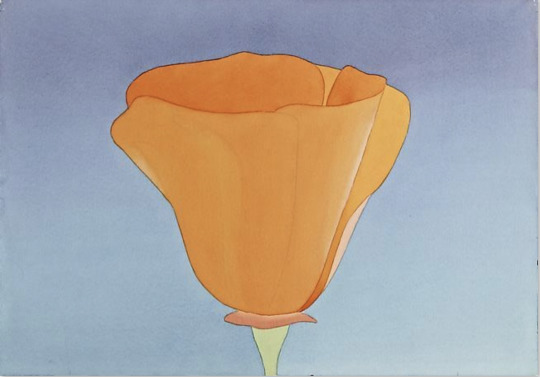

Artist Spotlight: Jeffrey Sincich

One thing that happened when listening to Jeffrey Sincich talk about his art is that Ace of Base’s 1993 hit "The Sign" kept playing in my head. This is because Sincich talks a lot about signs, particularly the ones you see walking around a city, which he replicates in quilted and mixed-medium works. Removed from their context, these signs make promises they can’t keep (FRUITS FOR 1$), intrigue and tantalize us (1 HOUR THE BEST), and provide space for gratitude (THANK YOU, THANK YOU, THANK YOU). Sincich shared his thoughts on quilting (not just for grandmothers!), what cities have what kind of signs (New York: "ghost signs high up on buildings that have been there for generations"), and how to be more cognizant of what’s around us, which leads to deeper appreciation for the hidden meanings behind all that we see. As the Swedish adage goes: “I saw the sign and it opened up my eyes."

Studio AHEAD: Your work is inspired by the built environment. Have you always lived in cities?

Jeffrey Sincich: San Francisco is the first big city that I have lived in. It is also the first one I ever visited. I grew up in suburban Florida near the Gulf of Mexico and moved to Portland, OR a little after college. Almost as soon as I moved to Portland, I became obsessed with moving to San Francisco. My first trip here was in middle school when I came to visit my uncle, who was living here at the time. Even as a kid I knew this city was special. San Francisco is so dense, and forces you to be around so many different types of people, which I love. Sharing walls and hallways with people instead of side yards makes me feel like I am part of something larger. I enjoy being one piece of the puzzle, rather than feeling like I am on my own.

Living in a city that is built to function for 800,000+ people has created so many interesting architectural details. Awnings that are connected to signs that are connected to lights that are connected to window grates that are connected to fences. I am constantly looking around and noticing how people have cobbled together materials to make things work. There is so much texture and variety in materials on every block. The inspiration is never ending. Being able to see all of this from the sidewalk versus looking at it across a front yard or from a car speeding by is priceless.

SA: You do a lot of quilting yet you are not an old woman. Please explain.

JS: Sexism in the art and craft world is nothing new. Is sewing only for women? Is welding just for men? They are both means of joining two materials together, yet they are often associated with gender. My dad taught me how to sew in high school when I wanted to make bicycle bags. I really enjoyed learning a new skill that allowed me to make an idea I had in my head a reality. I learned how to weld in college and loved it. Unfortunately, metalwork requires a lot more tools, resources and space than sewing.

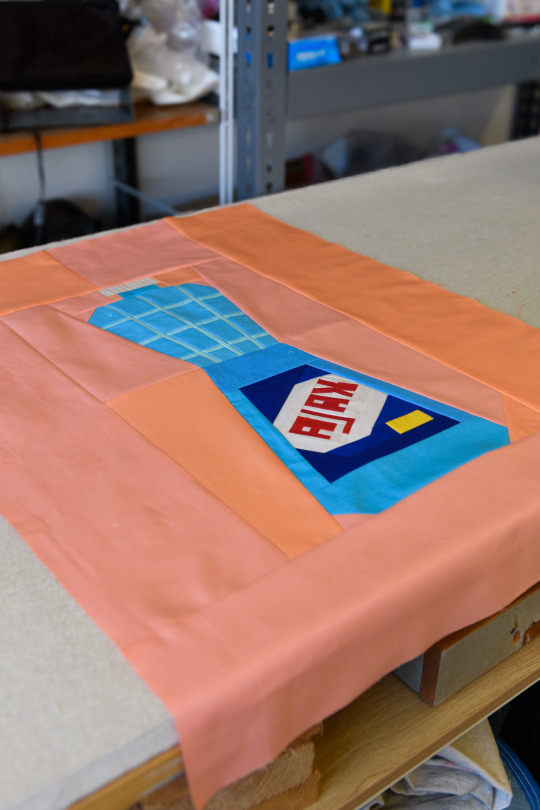

I have always been interested in craft and majored in ceramics in college. I found antique quilts so beautiful and often referenced their patchwork designs in my work. It seemed like a natural step to try and make a quilt. It was years after a failed attempt at making a quilt in college that I turned on my sewing machine again. After working full time as a sign painter for about five years, I wanted to start making art again. I decided to try making a quilt, this time inspired by the architecture I loved so much and got to paint signs on. A couple years and quilts later, COVID hit and I decided to turn my love of hand painted signs and lettering into quilts. It has been my focus ever since.

SA: A quilt is domestic. One thinks of fireplaces, interiors. I am particularly intrigued by your quilted works that represent outdoor spaces: street signs, façades, ads. Could you speak about this contrast?

JS: Signs can be personal. They are used to guide, inform, warn and sometimes manipulate you. Quilts are made to warm and comfort you. They often become hand-me-downs and keepsakes. They get worn down and are mended, holding family history. The same things can be true of signs. They fade and are touched up, sometimes professionally and sometimes not. Businesses can pass through different owners but still keep the same signs that have been up for generations. I like to reference the signs that have been cared for, or at least been maintained enough, to get a message across. Quilting objects from signs around the city like Clorox bleach and Marlboro cigarettes is my way of archiving the everyday items we often take for granted. I think that seeing these items as quilts makes them approachable in a more personal way.

SA: Are the window grates in front of your pieces like “All Makes & Models” or “Milk Beer” a comment on urban malaise?

JS: Yes and no. Window grates serve multiple functions. On one hand they are meant to keep people out. On the other they attract people with their beauty. I find this dichotomy of push and pull fascinating. The twists and curves that are used in the designs are gorgeous. Oftentimes they have hearts and sometimes the owner’s surname in them. They blend in with the architecture, filling asymmetrical voids and entryways. They cast beautiful shadows at night. The care and attention to detail put into the creation of these is amazing. That being said, they also serve to protect and evoke a sense of danger. They say look at me, but don’t you dare try to cross me.

I look forward to seeing these window grates every single day, on every block and on nearly every house. Their patterns are unique to San Francisco. I love adding a new design into my mental data bank. When I’m in other cities, I enjoy seeing what type of designs they use and how they are unique to that city's vernacular.

SA: What are some of your city-sign associations when in other cities? As a culture we tend to associate Las Vegas with neon, Paris with Guimard’s “Metropolitain,” New York with the colored circles of its subway…

JS: Cities can have unique sign styles, but more so individual neighborhoods. San Francisco’s Chinatown has many beautiful gold leaf window signs, often for family associations. The Mission has tons of beautifully stylized illustrations of the products sold in the storefronts. North Beach has giant, glowing neon signs outside the old strip clubs, begging you to come in. Los Angeles has endless hand painted signs, often in yellow, white, black, red and blue. They are faded by the relentless sun, showing off every brushstroke used to paint them. New York has ghost signs high up on buildings that have been there for generations, right next to freshly painted five story advertisements. These painted billboards still thrive in New York. The south has painted plywood highway signs that are barely holding on, advertising fresh oranges or alligator farms. It is really special to be able to walk around cities and see what old signs are still there, discovering which parts of their culture have stayed intact or have been left by the wayside.

SA: When you do step out of the city, where do you go?

JS: I go to West Marin. I don’t think there is a more beautiful natural place. It can bring me so much peace; the coastline, the rolling hills, the eucalyptus forests. Swimming in Tomales Bay is as close to swimming in Florida as it gets around here. It is beautiful in all types of weather: sunny, foggy and rainy. My favorite place is the Steep Ravine Cabins in Mount Tamalpais State Park. They have been around since 1938, and Dorothea Lange used to spend summers there with her family. They are these perfectly designed redwood structures that sit on the bottom of a cliff overlooking the ocean. I feel like I am in another world when I stay there, even though it’s just an hour away from my home. I have never been to an area that gives me this type of feeling, I love it.

SA: Is nature a type of sign?

JS: It can be. Sometimes it tells me to slow down and reminds me not to take things for granted. It is a reminder to try to stay out of the rat race more often. It can put me in a state of awe at how beautiful this world can be. But the one thing it always does is remind me that I can’t wait to get back to the city.

SA: Lastly, OPEN or CLOSED?

JS: Open, 24 Hours.

Photos by Ekaterina Izmestieva

#studioahead#northern california#bayarea#studio ahead#artistspotlight#san francisco#art#Jeffrey Sincich

0 notes

Text

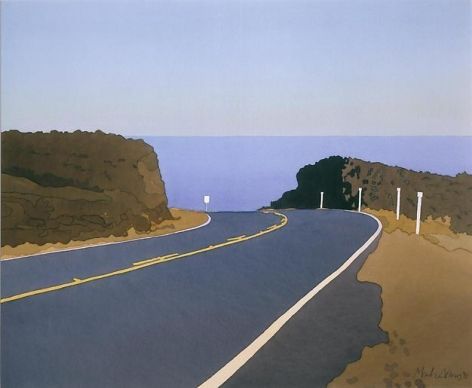

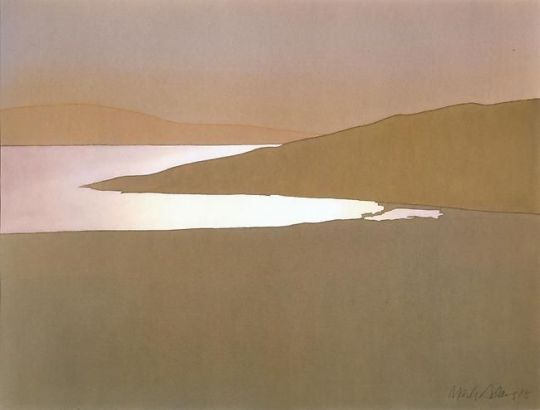

Artist Spotlight: Ted McCann

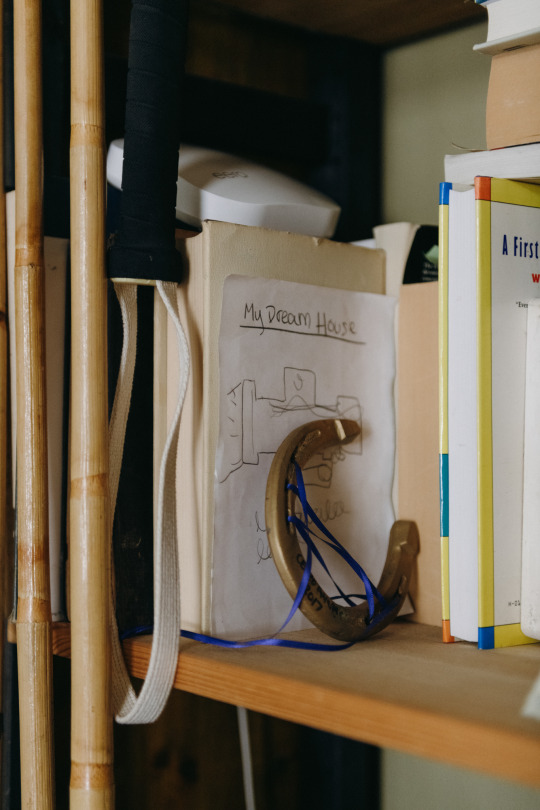

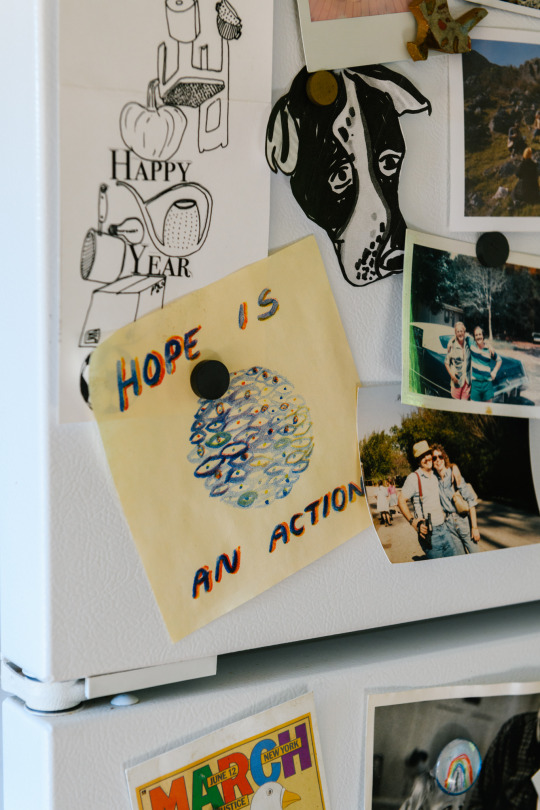

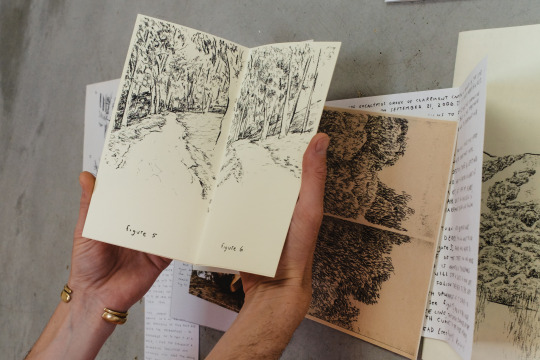

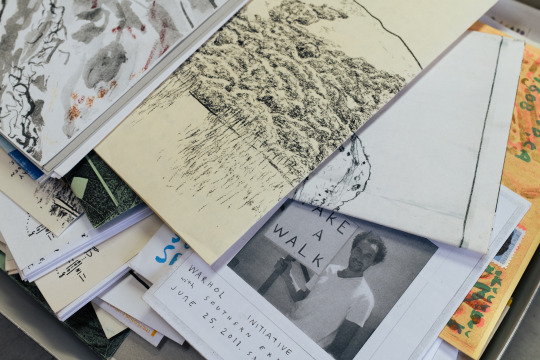

This month we spoke with artist and craftsman Ted McCann, whose musings on landscape and memory might be described as dreamy—but the sort of dream you have right before you wake to a startling moment of insight. Before moving to Petaluma from New York, McCann started a “California file of inspiration”—photos of regional trees, textiles, clayworks—to ease himself into his new surroundings. As much as we love this idea, we love even more the new surroundings themselves, with his home-studio at the center. We’re excited to share his wonderful journey, his reflections on art and Self, and his wise quips: “A home is a series of moments that you will encounter again and again and again.”

Studio AHEAD: I think we must start with your beautiful ranch in Petaluma, which you designed. Did working on your own home change the way you approach working on the homes of others?

Ted McCann: This house was such a great transitional vehicle for me, coming from the East Coast. In New York, I worked primarily on prewar apartments and townhouses, tuning into that period and finding ways to merge the old with the new. Similarly, our goal for the Petaluma house was to honor its original bones while giving it new life with more light, more openness, and unexpected materials and choices that all the same felt organic and inevitable.

So, my design approach has remained consistent, but working on a midcentury house required me to learn a whole new design vocabulary. Fortunately, I had plenty of time, as we bought the house and rented it out for two years before moving to Petaluma.

During that time, I started a California file of inspiration. I gathered images that spoke to how I wanted to live—everything from trees and plants, to textiles and rugs, to tiles and wood. They got me dreaming about the future and excited to make the move. One image in particular that I remember was of interior work by Charles de Lisle at the William Wurster Ranch, which like mine had lots of mahogany and painted brick. Realizing I would need to be drawing from an entirely new vocabulary, I pretty much threw out all my go-to New York Prewar sample materials and started over.

When we arrived in Petaluma, the first thing I did was rip out the old shag wall-to-wall carpet, brass chandeliers, and over the calico brick fireplace. By stripping out all of those things, I could see the future. It didn’t feel that far off. But it was. The house hadn’t been touched since 1955, and there was an overwhelming amount of work for one person. Still these images kept me excited for what was to come and helped guide me through the entire two-year renovation.

The whole experience taught me the importance of a guiding vision. Now, when I’m approached for a commission I always like to start the conversation through images. I encourage people to

share whatever it is that they love, whether it’s architecture, design, art, or cinema, music, or whatever! This conversation continues until we find a vision that we’re both excited about.

Another thing I learned from working on my own house is to push people to expect more. A home is a series of moments that you will encounter again and again and again. Why not make the most of those moments? Expect more from your kitchen or study or especially, for God’s sake, your powder room!

My favorite place is my shower. It’s the heated floor, the combination of color, light and materials. It’s a real sensory experience that surprises me again and again, every day.

In my woodworking, I try to make things with the same potential to please. Sometimes it’s the smallest of details that can do this—a tweak on typical proportions, an evocative color, or a satisfying handle. Working on my home deepened my belief in better living though art and thoughtful design. I like to think that through my work I can share that with others.

Studio AHEAD: With that answer you are also a poet. I’m curious if there is a line between your furniture design and your art—if you think before you start this is going to be art or this is going to be furniture or you start one but realize it might be better as the other, and what might trigger that response.

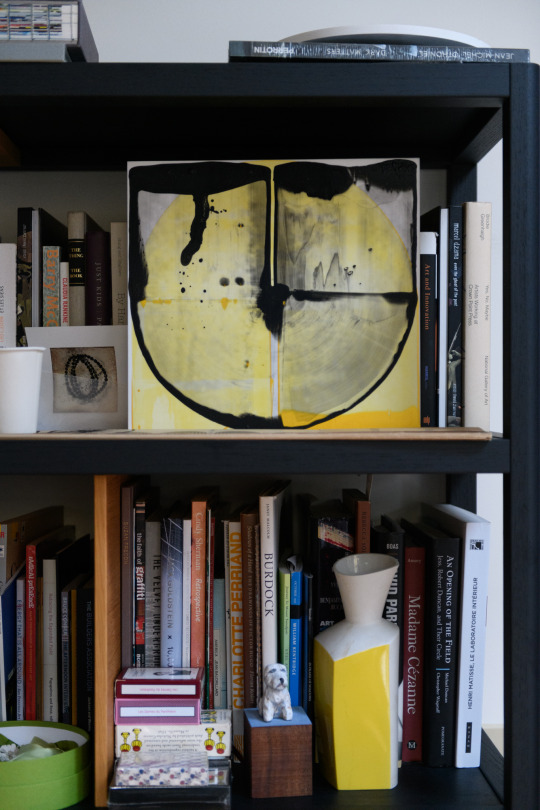

Ted McCann: I’ll start by saying, Yes, I do always know at the outset whether I’m going to create a functional piece of furniture or cabinetry, or a sculpture. With my woodworking commissions there is a clear intention from the outset; I know I’m building a table or a bench. But my approach to art is super intuitive; the work tends to reveal what it wants to be as I go along. Either way, the line between art and design is often at play in my work.

I lived in New York City for twenty years before moving west. And in those years, I lived a compartmentalized existence. I had a studio where I made art, and a woodshop where I built cabinetry for the spaces I was renovating through my boutique contracting business. At that time, my professional work was focused on execution. Often, I wasn’t artistically invested in the projects. I didn’t know how to merge my two identities as woodworker and sculptor.

I think living this bifurcated existence, and never having enough time to focus on my personal work made me unhappier than I realized, and that came out in the art I was making during these years. I didn’t see it then, but what I was making for myself in the studio at that time really reflected the friction and discontent that can come to a practical, responsible, but unfulfilled person.

It's crazy looking back how that discontent was right on the surface of my work. I did a series of self-portrait paintings that just showed my eyes, peering out from a cutout in a discarded refrigerator box. They were self-portraits that I think reflected how I felt somewhat invisible and also trapped in an urban landscape. In the same period, I made a series of “personal survival units” that seemed fitting for use on the Antarctic or the moon. One sculpture you wore on your back; it contained a personal surrender flag to be deployed as needed. Another was a portable tripod beacon that sent out a flashing light and the sub base notes of a Keith Sweat song, luring a stranger to the source, where they would find an always warm cup of coffee. Another series of paintings were monochrome panels in bright autobody lacquer, with the dits and dahs of morse code extruded across the surface. These paintings also tapped into a romantic, existential longing. The code spelled out wistful phrases like “remember me” from Henry Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas and “perfect summer,” a headline from a fashion magazine editorial. These personal works were completely at odds with the impersonal jobs I was executing in my woodshop.

Happily, I’ve come to understand the importance of approaching commissioned projects from a more sculptural or artistic sensibility than I did in the past. These days, I still make my living building for others, but everything that leaves my studio—from paintings and sculptures to entirely functional furniture and cabinetry—reflects my sensibility in some way. My studio goes though waves of time focused on a kitchen or library commission and back to more personal art projects. But often, the commissioned works are in strong dialogue with my artwork and are better for it. In the end, all of my work ends up feeling like mine because it employs the same level of finish and craftsmanship.

This is only possible because I’m more selective about the jobs I take on than I once was. It can be scary to pass up paid work, but I’ve realized that by saying no to jobs that don’t speak to my soul, I’m opening myself and my time up to projects that do.

I know you didn’t ask for that backstory, but there it is.

Studio AHEAD: No, we love a backstory. There is always a backstory to every object, design, taste. We want to give voice to that. Actually, tell us more of your backstory. You grew up in New York and Barcelona, or what we might call the Far East and the Further East. How did you make it out West?

Ted McCann: I always thought I’d get back to Spain to live with my family one day, but never did. Still, I’m writing to you on a plane to Madrid. It seems all my stories about my teenage years in Barcelona planted a seed with my son, who is now spending a high school year abroad in Zaragoza.

Some people are forever New Yorkers. As much as I love that city, turns out I wasn’t. Every weekend, my wife and I would schlep our two young sons and all of their stuff from our Brooklyn apartment to the North Fork of Long Island, where we had a cottage. We lived out of tote bags and were eternally packing and unpacking groceries. Between my studio in Queens, jobs all over Manhattan, and the Brooklyn to Long Island commute, it was all so hectic. Not to mention that half my brain was always trying to remember where I’d parked the car.

One day I was with my family on vacation and we stopped in Petaluma for a delicious sandwich at a downtown spot called Della Fattoria. I loved the Wild West downtown combined with the somewhat gritty industrial grain silos and the fact that every road led to beautiful rolling gold hills. And I don’t know if other asthmatics are like me, but I love breathing in hot, dry air. We left thinking, Maybe Petaluma? With help from my father-in-law, who lives in nearby Glen Ellen, we eventually found and bought a Petaluma midcentury house. This place, where we could live, work, and be in nature all at once, seemed like the antidote to our scattered New York life. But we weren’t yet ready to leave the city, so we rented out the house, knowing it was there for us when the time felt right.

Two years later, I left my work and all my clients behind and started my career from scratch. My wife, Genevieve Field, is a writer, so her career was much more portable, thankfully. This afforded me time to renovate our home and build our dream studios on our property. This project was the slow transition I needed to process a life-changing move.

Studio AHEAD: Now that you are here, what role do ideas of place have in what you create? In your approach to craft?

Ted McCann: I never thought about my living space in such poetic terms as I do now. I’m sure my contemplative state has something to do with middle age, but this beautiful and quiet place also plays its part. Sonoma County and the Marin coast are so dramatic, it’s hard not to be affected. Every time I go to San Francisco, I look forward to the drive back over the Big Red Bridge and—poof!—I’m passing Mt. Tamalpias.

There’s such a fluid conversation between humans and nature, indoors and outdoors, in California that never really stops. Our mild winters mean nature is accessible and comfortable year-round. I love the rolling green hills in winter, and the hot summer days eased by the cool nights. The climate still feels foreign to me, but in a good way, like listening to a poem that you don’t really understand but it doesn’t matter because the words and rhythms just sound good.

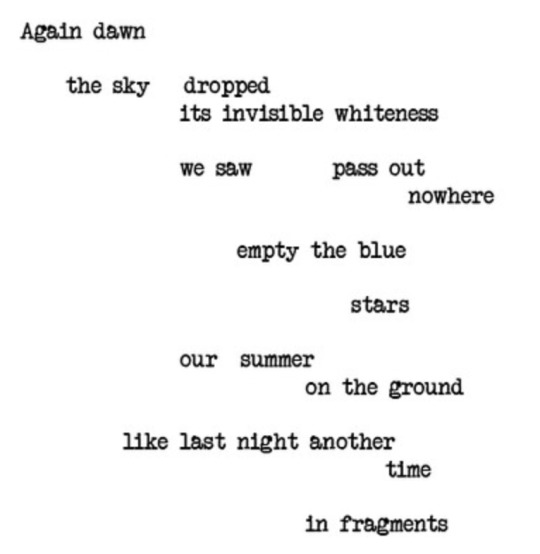

I’ve always thought sculpture and poetry shared a language—both use shape and texture to elicit feeling. My father-in-law, John Field, is a poet. He writes beautifully about getting older, and while I don’t always understand his poems, I know how they make me feel. The language of

aging is also present in the drama of the coast—the wind-whipped eucalyptuses and shifting cliffs.... Living here, I’ve become more attuned to the sensory elements of living spaces. This is something I think Studio AHEAD is really good at: creating poetic, sculptural, atmospheric places.

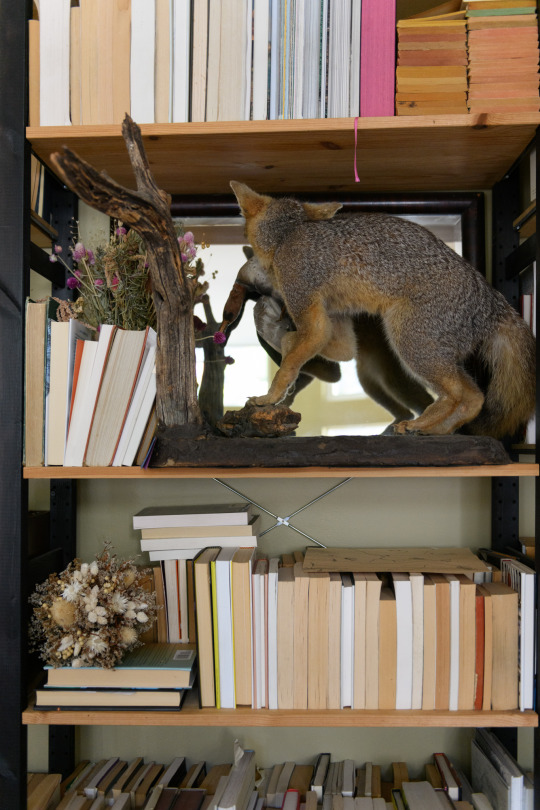

I’ve always found inspiration in found objects. Living in New York, I used to photograph and collect things I encountered on the streets. These days, I have to go to the Pick n Pull salvage yard and pay for my inspiring junk. At the beach, I’m always looking for and collecting flotsam and jetsam, which are also scarcer here. Bruno Munari made The Sea as Craftsman, a small book of writings and pictures of bits of rope and things that he found washed up. I love his concept of the sea as carpenter: manmade objects that make their way into the sea are reshaped, polished, and returned abstracted from what they once were. I have an ongoing series of sculptures where I enlarge the scale of plastic objects I find on the beach, carve them out of wood, and paint them black. On one hand, these pieces are simply shapes that move me, but I think they’re really about the transformative power of nature over all things.

Studio AHEAD: What are some of your favorite places here? And what is one place you miss in New York?

Ted McCann: I’ve run hundreds of miles in the rolling hills of Helen Putnam Park, and it feels like church most every time.

The Marin coast is something else. Just driving there is good therapy: Bodega Avenue is stunning all the way to the coast.

Another driving moment: there’s a section of Stage Gulch Road between Petaluma and Sonoma that gets me every time. Especially when the yellow mustard fields are in bloom. I feel so lucky to be able to enjoy these “spaces in between.”

And if I can mention one more, I’m super excited about the Petaluma River Park, where I’m a volunteer. It’s a new 24-acre space that’s just getting its start. A Mark di Suvero sculpture installed in October has really created a sense of place.

Every time I go back to New York, I worry it will break my heart to leave again. But the city is constantly changing and I have a hard time connecting with the place where I spent my twenties and thirties. I still love it though. I always pop my head into the bar where I met my wife, Sweet and Vicious on Spring Street near the Bowery. It was the exact location where my life changed.

Another place that I love and few people seem to know about is the Nevelson Chapel in Midtown Manhattan, created by the late artist Louise Nevelson. Stepping out of the chaos of

Midtown into the quiet and often empty room in Saint Peter’s Church feels like going to the source of it all.

But the place I miss most is a series of places. I often ran at night when I lived in New York. From Clinton Hill, Brooklyn, I’d run across the Brooklyn Bridge, past the Supreme Court Building, up through Chinatown and the Lower East Side, then back home via the Williamsburg Bridge. The streets would finally be quiet and the buildings lit up. It was a rare time when New York was at rest and I felt I had it all to myself.

Photos by Ekaterina Izmestieva

0 notes

Text

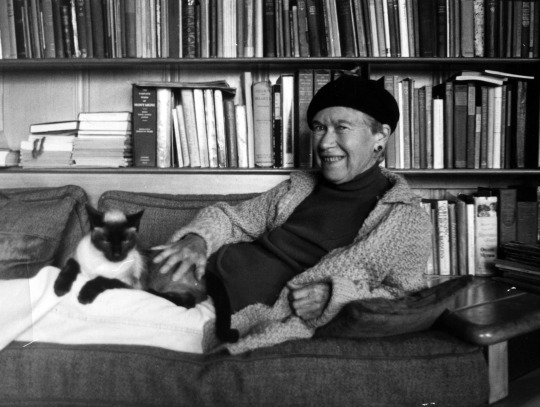

Curator Spotlight: Natasha Boas

We’re ringing in the new year with a firecracker: one of our most hilarious, crazy features ever, an interview with Natasha Boas, whose sparkling wit is matched only by her taste in literature and chairs. You’ll have to read below to understand, but we’ll say now that this is a woman who was once Jacques Derrida's student and sat on his kitchen chairs in his apartment in Paris. A conversation with Boas, an independent scholar and curator (and thinker), had us traipsing all over the noosphere and our own backyard in San Francisco, where she became our tour guide to the hidden currents of a city we thought we knew well.

Studio AHEAD: In your home you have several towers of precariously stacked books. We’re going to name a few and would like you tell us the perfect chair/sofa/magic carpet on which to read them:

La honte (Annie Ernaux)

Natasha Boas: I have always been a huge fan of Ernaux’s and have read everything she has written in French, and then in 2022 she received the Nobel Prize in Literature so her novels are finally more available in English. La honte is about the shame a young woman experiences about her childhood and the woman she becomes. It’s autofiction, one of my favorite genres. I think I would suggest reading La honte on any Madame Récamier daybed—perhaps specifically on my antique nineteenth-century French iron folding bed. I grew up with it as my childhood bed and it has tiny wheels—when we once had an earthquake in San Francisco in the 1970s, I remember waking up having rolled across by bedroom from the garden corner to my fireplace.

SA: Specters of Marx (Jacques Derrida)

NB: For Derrida, the spirit or “ghost” of Marx was even more relevant after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. This essay was the plenary address of "Whither Marxism?," a conference on the future of Marxism held at the University of California, Riverside in 1993. Derrida was my professor in Paris and a very modest man who would have wanted us to read his book on a simple kitchen chair—perhaps a Charlotte Perriand Bausch chair from the 50s that came secondhand with his humble apartment—where the caning is damaged and used and it is broken and somewhat imbalanced.

SA: Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (Sigmund Freud)

NB: This book contains the iconic essay in which Freud reveals his famous Oedipal theory among other things. It should be read in your mother’s lap—haha! No, it should be read on Freud’s divan couch of course! It may be the most famous couch in history and can be admired in Freud’s study in London at The Freud Museum at 20 Maresfield Gardens in the Hampstead neighborhood. The term “on the couch” became the euphemism for what psychiatrists do because of this very couch shaped like a chaise long with a Persian rug laid over it. Of course, I contributed to a fundraiser launched in 2013 to help reupholster the legendary couch. It seemed very important to me at the time.

SA: Leonora Carrington: The Story of the Last Egg (Leonora Carrington)

NB: This book is the accompanying catalogue to Gallery Wendi Norris’s 2019 exhibition of the same name in New York City. In addition to the show, the gallery hosted a two-day symposium on Carrington. It began with a dramatic reading of Leonora's play, titled Opus Siniestrus: The Story of the Last Egg, which in many ways predicts the dystopian situation of women’s reproductive rights today. My talk “The Leonora Carrington Effect: What We Can Learn from Leonora Carrington Today” became an essay for the book.

These ideas on the relevance of Carrington today resonated a year later at the Venice Biennale “Milk of Dreams” with its focus on Carrington and other historic Surrealist women artists. I wrote my dissertation years ago on this seminal modernist movement in art, which continues to influence my work. Currently, I have curated the exhibition on the post-Surrealist Gertrud Parker: The Possible at Marin MOCA, which includes Leonora Carrington, Leonor Fini, Alice Rahon and other influential Surrealist women. It is up through March 31 and I highly recommend a visit. It also features the famous Dynaton artists Luchita Hurtado, Wolfgang Paalen, and Gordon Onslow Ford, who convened in Inverness in west Marin County last century.

I think I would read The Story of the Egg on the bed that the Surrealist artist Max Ernst made for his wife, the artist Dorothea Tanning. It is said that she hated the bed and hid it out of view in the basement of their Provence house, but it is currently being shown on the top floor at a small regional Max Ernst museum in Seillans, near my family house in the Var, Cote d’Azur region. It’s a bizarre six-post structure with a mirror, green metal leaves, a faux brown fur bedspread and several circular paintings attached to it—but seems like the perfect bed for lounging on to read this provocative book.

SA: You are an expert on countercultures and in particular the Mission School. Is there anything you have learned from them—whether related to art or not—that you apply to how you interact, live in, go about San Francisco? This is of course a movement whose members reimagined what was around them.

NB: Yes, I have always been drawn to countercultures, alternative art movements, and under-recognized artists. What drew me to the Mission School artists was that it was an “affective” community—one based on shared sensitivities, a shared neighborhood, and friendships. Graffiti, studio painting and the San Francisco Art Institute were touch points for the group. In many ways I see this group of artists as a continuation of another SFAI group, the Rat Bastards Protective Association with Jay deFeo, Bruce and Jean Conner, Manuel Neri, and others. In fact, Ruby Neri, Manuel’s daughter, who was raised in Inverness and educated at SFAI, literally connects the two movements. I learned that there can be a correlation between street art and studio practice through her, Barry McGee, Alicia McCarthy, Chris Johanson, and Margaret Kilgallen.

These artists were not precious, they used simple materials often culled from garbage found in the city and they always included their friends’ work in their exhibitions, and they still do. That is very much the “Bay Way” of making art. It has influenced my way of curating too. I am not afraid of the heteroclitic or telling new stories. I just curated a show this fall: “Old Friends/New Friends” at Creativity Explored, which is a studio that supports neurodiverse artists or what we used to refer to in art history as “outsider artists” and the expanded Mission school artist community.

I grew up in SF in the 1970s. I even lived at the now defunct radical artist colony The Farm founded by the conceptual artist Bonnie Ora Sherk under what was then Army Street overpass and now Cesar Chavez. I worked at the Café Trieste in North Beach as a barista and served the likes of Allen Ginsburg. I read my poetry at City Lights Book Store and saw the Dead Kennedys perform at The Mabuhay Gardens. We were around when Harvey Milk was assassinated and when SFMOMA was on the fourth floor of the War Memorial Veterans building on Van Ness Avenue. This group of Mission School artists are my generation. We vibe on the same San Francisco history.

SA: I am curious as to what happens in your curation when you bring institutional outsiders inside the institution. Perhaps nothing happens. Perhaps it changes everything. Perhaps it ruins everything.

NB: In my experience—magic happens. But I have always taken risks—like bringing a trailer, which I bought with the Indigenous artist Brad Kahlhamer at an Arizona swap meet for a hundred dollars, into a museum gallery to create a nomadic studio space. We had to fumigate the trailer to make it museum compliant and we built out a proscenium so we could also use it as a stage for local Native performances. The exhibition was appropriately entitled SWAP MEET and played on all the valences of cultural exchange.

SA: You speak so much about San Francisco’s history, and so much has changed, that I wonder if counterculture is still possible in this city?

NB: Yes—it is always possible especially in our city with its cyclical history of boom and bust! There is always some kind of counterculture operating. We just need to ask “which culture is counterculture countering?” and then we can identify it. And we should always be brave enough to counter culture through the sub, the underground, the transversal. I just participated in a show at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris called The Termite Bites and it looked at artists who are practicing—literally and figuratively—below ground.

SA: We always ask the person interviewed how they came to California. We’ll pose this question to you with a twist. How did you come to California? And can you trace the history of how one piece of artwork that you own came into your possession here in California?

NB: My family came to SF from France in the late 1960s as part of a larger movement of young people seeking alternative lifestyles and new ideas—I was raised in a vibrant multicultural city and went to a French lycée and roamed freely around town on Muni. Later, I moved east for college and then lived and worked as a curator and professor in New York and Paris for over 20 years, when I returned back to the Bay to raise my family.

Most of my collection is from artists I have worked closely with over the years in all three places—either gifted or swapped. I am particularly attached to an Etel Adnan (1925-2021) Mount Tamalpais artwork I have from my time working with her in Paris. Adnan—who was born in Beirut, Lebanon, died in Paris, and lived an important part of her life with her life companion, the artist Simone Fattal in Sausalito—is a transnational link for me between my two homes and two cultures—in her case three cultures. Her poems and drawings in the book Journey to Mount Tamalpais speak to me the most; it has been re-edited recently by my friend Omar Berrada.

SA: Lastly, in the spirit of Guy Debord and the Situationists, if you were doing a dérive-style walk around San Francisco, where might it take you?

NB: My dérive would always lead me back to the Lyon street steps at Broadway. My friend Marc Zegans just published a book of poems about this important passage way in the city. Our SF was more of a village, pre-tech booms. I grew up and went to high school in Presidio Heights. It was very sleepy. We lived on those steps as teens, overlooking the bridge. We had our first kisses there, smoked our first joints, played the guitar, the city was ours.

Photos by Ekaterina Izmestieva

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Artist Spotlight: NJ Roseti

This month we spoke, or touched wavelengths with, Oakland based artist NJ Roseti, whose furniture designs we've been having a lot of fun looking at and thinking about and using in our own work. So look at them! and then come back to this interview, where we try to find the axiom behind their Euclidean logics.

Studio AHEAD: The first things that come to mind when looking at your most recent pieces are: an original Gameboy with the blue Pokemon cartridge in the back, Ettore Sottsass, Platonic essences, Minecraft, Art Deco, the word "wobble". How close/far away are we?

NJ Roseti: These references are great and not all of these associations are new to my ears. I think the one that rings most true out of what you said for my work is the Platonic essence. Many of my pieces represent the moment in time of emergence or distortion and so by Plato's definition are less real than the Forms which are eternal, unchanging and complete.

SA: Give us a line or two about lines. Often yours are straight. But then—for instance in the Just Like Always table lamp—these lines veer off in unexpected directions. Where do they take you? Where should they take us?

NR: Lines, whether continuous or broken, symbolize to me the continuum of time, where the unbroken line represents the seamless flow of the past, while the broken line signifies the ongoing journey into the future.

SA: What lines have you crossed or followed to get here?

NR: Currently, it's challenging to articulate a distinctive perspective as an artist amidst the myriad of voices from the past and present. It has taken some time for me to clarify my thoughts and find a meaningful expression, having to sacrifice certain things like living at the same standards that other people live, being close to family and focusing on my personal life. Although I haven't reached my destination, I sense the beginnings of crafting a world where I can dwell happily.

SA: In these interviews, we always ask about materiality. Your designs have an almost ironic relation to their materials, as in the Love Before Now trays, with their exaggerated wood marks, or your love of primary colors. Perhaps you have a word or two to say about this; perhaps you will say it is not ironic at all.

NR: The selection of my materials is closely tied to irony. Marquetry, a deeply historical and traditional technique known for its ornate motifs, becomes a means for me to comment on the classical role of wood, highlighting the ironic contrast of its historical significance amid the digital age's prevailing trends.

SA: About the digital: you design with a computer and by hand. Is there a tension in this? I am thinking in contrasts: robotic precision/human imperfection, cold machine/warm body, preprogrammed/spontaneity.

NR: I see no tension actually; in fact, I find the particular connection between artist and computers to be exceptionally beautiful when it’s used as a mere tool. It enhances spontaneity, facilitates iteration, and expands our creative possibilities. It’s the crafting process that is the part that is paid with time, so together it’s overall quite balanced. In this era where computers effortlessly emulate imperfect and organic forms, my exploration with rigid lines and rectilinear shapes aims to prompt viewers to appreciate the inherent perfection achievable on a computer through the precision of geometric forms. I also want to clarify that I’m talking strictly about computers and not AI. I don’t in any way endorse the use of AI in creative fields.

SA: When You Forget. To You. I Just Remembered. I Should Be Now. What’s the deal with the titles?

NR: My works are all deeply personal and I convey my meaning through a process akin to crafting a poem. To label a poem as “Rhythmic words arranged on a page” would do the poem injustice and the overarching meaning would be lost.

SA: Tell us one remarkable thing you’ve sat on.

NR: Sitting in the Noodle Throne by Caleb Ferris feels like you are sitting on an icon that will be remembered in the books.

Photos by Ekaterina Izmestieva

0 notes

Text

Studio Spotlight: Headlands Center for the Arts

The Marin Headlands is just north of San Francisco but worlds away. About halfway along its cape, home to some of the Bay Area's richest biodiversity, is a cluster of former military buildings that now house the Headlands Center for the Arts, unlike any museum or gallery in the city because its art is made on site. Its artists-in-residency program attracts international talent, but the Center keeps things local with a series of open studios, exhibitions, and artist talks for tourist and townie alike. We spoke with Mari Robles, executive director of the Center since 2021, about what it is like to build community in a place where you can see more stars in the sky than people on the streets.

Studio AHEAD: Hi, Mari! Tell us about how you came to Marin. Prior to your start at the Headlands, you were living in New York City, which is pretty much the opposite in terms of geography and pace of life.

Mari Robles: Marin is opposite in every way to NYC (and Chicago!)—coyotes, owls, stars, quiet! Like so many people, I started exploring new parts of myself during the pandemic, and the opportunity to extend that personal adventure to a new home and such an inspiring new mission felt right. And on a very basic level, how could you say no to such a beautiful place?

Studio AHEAD: What’s been the biggest change?

Mari Robles: I welcomed the change of pace, but I must admit, the first blackout in the Headlands was shocking. I didn’t realize just how dark it could get. That, plus the fact that you can’t get food delivered or grab a taxi out here, can make you feel removed from the rest of the world. Ultimately, however, it’s that remove that allows for a great deal of reflection and an opportunity to commune with nature—all things that make Headlands such a special place for artists, and I’m happy to say, me as well.

Studio AHEAD: Has New York influenced how you approach your current position as executive director? Does Marin affect how you look back at your years in NYC?

Mari Robles: While I was working at The Met, I thought a lot about the conversation between local and global communities, specifically how they seem to be moving on a parallel path. We are living in a time when the most globally impactful thing you can do is to be hyper-responsive to your most immediate community. It’s so easy to overlook, but the impact of that approach radiates outwards and can influence the wider world in such meaningful ways. This was true of my experience in NYC, and based on my experiences so far, I also believe it’s true of the Bay Area.

Studio AHEAD: I love your idea of global and local moving in parallel—that’s a great way to describe how we work as designers.

Perhaps the biggest change from New York, and Chicago and Miami where you have also lived, is that there are far fewer people where you are. Does this create challenges in terms of building a community? We know the AIR program is doing a great job bringing people together….

Mari Robles: Recently, one of our summer residents called Headlands a “parenthesis in the world,” and that really struck me—this place is really so singular in the arts community. Our campus has a strong connection to the rest of the Bay Area while being distinctly separated from it, physically and psychologically. That means it can provide you with moments of heightened attention in which you’re deeply present with yourself, the artwork you’re seeing, your ideas, and your community. In order to experience this, however, you have to surrender to the inconvenience of traveling to this place. And depending on your starting point, that can indeed be daunting. But for those who are undeterred, that inconvenience is always worth it.

Studio AHEAD: It’s worth it definitely. OK! Let’s talk actual art. A theme we noticed in reading a lot of the current art residents’ statements is the role California’s natural environment plays on their ways of making art. Certainly in our own work, we are always bringing the countryside into our design decisions. When deciding residents, are you looking for artists who are attuned to their surroundings?

Mari Robles: Headlands supports artists who are at an inflection point in their careers. This means they are primed to explore a promising new direction or idea, and that the space, time, resources, and affirmation we offer them will help them plunge deeper into themselves and their work than they might anywhere else. We essentially want to incubate their next artistic incarnation and give them what they need to bring their creative practice to the next level.

One of the most beautiful aspects of our residency program is that we have artists from all disciplines from all over the world—from visual artists to writers, dancers to performers, and musicians, all with a mindset of tinkering and exchange. What they share with each other and those who visit their studios—particularly during our Open House events—is often raw and vulnerable. In my mind, seeing a work of art take shape is a defining experience at Headlands. Anyone and anything here can be a catalyst toward a real creative breakthrough.

Currently, VictoriaShen, an experimental sound artist from the Bay, is in residency in our Project Space. She’s making instruments using kites, her body, and obsolete technology, and opens her studio five days a week for everyone to see.

Studio AHEAD: Do you do your own creative work? Or are you more of an organizer/director?

Mari Robles: I did play violin in my twenties, but these days, I’m an avid art lover, supporter, and leader who practices creativity every day in my personal and professional life. I’m not an artist, but I believe in the transformative power of creativity and have seen my life become richer and more meaningful whenever I approach a situation through the lens of possibility and worldmaking.

Studio AHEAD: Speaking of worldmaking, what are some areas—a neighborhood, a favorite vista—that have most delighted you since moving here?

Mari Robles: In Marin, I recently discovered the Pelican Inn by Muir Beach, and I cannot get enough of the cozy atmosphere and delicious meals. I also frequent Sandrino’s in Sausalito and just love their pizzas, wine selection, and tremendously warm hospitality. And any time I need to be replenished, I take a drive to Hawk Hill; it’s humbling to see the beauty of San Francisco from that distance and then turn towards the vastness of the Pacific Ocean.

Over in the city, going to see a talk at City Arts has become one of my favorite things to do. I really enjoy the range of critical conversations they organize.

Lastly, I’ve also seen a few amazing concerts at the Fox Theater in Oakland—Grace Jones, Nils Frahm—followed by some of the most delicious street food. I love the energy and living of those moments.

Studio AHEAD: Thank you, Mari!

Photos by Ekaterina Izmestieva

#studioahead#marincounty#marin headlands#headlands center for the art#art#bayarea#northern california#san francisco#artistspotlight#gallery#studio ahead

1 note

·

View note

Text

Gallery Spotlight: Aida Jones

We at Studio AHEAD are excited to announce our latest exhibition, The Lily Too Shall Function, on display at The Jones Institute and the Minnesota Street Project starting November 3. As a sneak peak, we spoke this month with Aïda Jones, founder of The Jones Institute, who shared with us the history of the home gallery, a few thoughts on our show, and what San Francisco was like in the 1990s.

Studio AHEAD: The first striking thing about the Jones Institute is that it is run out of your living room. Can you share with us the history of how this came to be?

Aïda Jones: Impulse was the catalyst. An artist friend was forlorn after being rejected by a gallery and, instinctively, I responded, “I’ll have a show for you.”

It was a leap of faith where Matt Dick, Ruth Kneass, Tjarn Sato, Fletcher, Anton Stuebner, Michael Lee, Wendy Norris, Regina Tsasis, and many many others, generously helped transform my living room into The Jones Institute.

Studio AHEAD: Were there other contexts?

Aïda Jones: The home is the original gallery. We still visit homes—the Uffizi, the Louvre, the Frick—that are now museums. The Walker Art Center in Minneapolis began in TB Walker’s home in the late 19th century and in New York in the 50s, Leo Castelli converted his living room into his first gallery. The New York Times had a wonderful article about apartment galleries a few years back.

Studio AHEAD: Perhaps 500 Capp is San Francisco’s most famous example. Who were your guiding lights in setting this up?

Aïda Jones: I love the idea of shaping culture from the fringes. Of bringing a traditional and formal construct into the domestic space.

Guiding lights are everywhere. Walk out your door and you’ll find thousands of inspirations: the drunk at the wharf, everything in Chinatown, the dahlias in the park, the art in the TL, vendors in the Mission, the cook at Red’s, the amateur opera singer next door rehearsing.

Studio AHEAD: What sort of advantages does this… let’s say DIY approach… bring?

Aïda Jones: Let's not say DIY.

Studio AHEAD: Then what would you call it? Certainly the space itself affects how people view the art.

Aïda Jones: If we have to label it, maybe call it an alternative space. And you’re right, space absolutely affects how people view art. It permeates every bit of their experience. When art is in a home, the sense of place opens them up—the art itself changes the space, it’s a symbiotic relationship you won’t have within the white box. And The Jones Institute is not a commercial place so most people find communing with art is different.

Studio AHEAD: Tell us about a recent exhibition from curator Shirley Watts. Would this be a show a more mainstream gallery could put on?

Aïda Jones: Yes and no. While individually the artists from that show (Gail Wright and Megan Gafford, for example) are exhibited in mainstream galleries, the whole of Altered States would have been impossible. Where else could you sit in a backyard, listening to an audio performance of a brain dissection (Erica van Loon) after taking in Megan Gafford’s irradiated daisies and an Erin Espelie RGB video in the main gallery?

Studio AHEAD: Nowhere else! How does our show, The Lily Too Shall Function, fit into this?

Aïda Jones: The Lily Too Shall Function, being guest curated by Homan and Elena, feels very connected to our programming. First, they chose three Northern California artists among the cohort we choose to exhibit here; and second, they are working their distinct point of view within the domestic space, marrying art with how we live. Very much in our founding ethos. We also have a deep belief in sharing the artistic process, so screening a film of the artists at our satellite location in Minnesota Street Project just makes sense.

Studio AHEAD: You and Homan were speaking off-the-record about the 1990s, on which there is currently a lot of nostalgia in mainstream American culture. What elements of the 90s would you like to see transplanted into the 2020s?

Aïda Jones: This is specific to San Francisco where we are on the edge of the world. The experimentation, the casual spontaneity, the lack of preciousness and belief you could do anything.

In the 90s, I founded AvidFan, a theatre company, and when I cast two actors (who were also female) in The Zoo Story and then True West—this to the New York Times was radical, but in San Francisco, no one blinked.

It happened because of this place as it existed then. The space and freedom. The whole Bay was wide open with possibility (and low rents!). Such amazing support for artists, from studios and rehearsal spaces for musicians, filmmakers, comedians, photographers, spoken word poets, writers, hip-hop/modern/ballet dancers to performance venues and theaters (& a cowboy store on Valencia), many underground & well-known support structures like Film Arts Foundation, New Langton Arts, New College, and so many others.

For a peek into that era see the New Yorker article of the photographer Chloe Sherman’s Renegades (and then buy the book).

Studio AHEAD: What aspect of the 2020s would you have liked to see back in the 90s?

Aïda Jones: The lovely, well-kept city parks. The absence of lingerie shows in downtown bars.

Studio AHEAD: We like to end with some cultural spaces/people in Northern California you’d like to shed light on.

Aïda Jones: Aside from each and every artist I've shown?

Studio AHEAD: Yes.

Aïda Jones: Here is an incomplete list: Aimee Sioux, Reed Awakening, TamaOne, The Farm Stand Art & Music program, Stud Country Queer Line Dancing, Slash Art, For You, the Bolinas Museum, African American Cultural Center, Dancers' Group, Auntie Charlie’s, Werkshack, CCSF Film Department, Arborica, the promise of a NorCal Pacific Standard Time, Catholic Charities’ homeless family shelters, Canyon Cinema, the Bay View Newspaper, Everything the band, Albert Lee, Natural Discourse, NAID, Cushion Works, Lynette Betancur, Donald Guravich, Rachel Marino, the new extension of trails in Marin’s redwood preserve, Originals Vinyl, Li Po, Artists Television Access, CounterPulse, RCA Beach, Day Moon Bread, whatever Natasha Boas is up to, 120710 in Berkeley, Winslow House…

Studio AHEAD: Thank you!

Photos by Ekaterina Izmestieva

1 note

·

View note

Text

Artist Spotlight: John Gnorski

When we asked John Gnorski what on earth are EARTH BABIES, he took us on a subterranean journey to meet them. Or at least that's how it felt. Hearing John speak about his creative process certainly takes you all over, even into your subconsciousness, about which he has a lot to say. His art is full of strange landscapes, strange portraits, strange figures. Our current fave is one from his Clouds Roll By Like A Train In The Sky series not because of its great title, or because the clouds might actually be birds or blossoms, but because peeking through the print's ink is the grain of the woodblock, reminding us of the materiality that grounds all our work, no matter how wildly dreamt.

Studio AHEAD: John, your bio is mysteriously pithy: “Born in Alexandria, Virginia, living/ working in Point Reyes Station, CA.” What brought you to the other side of the country?

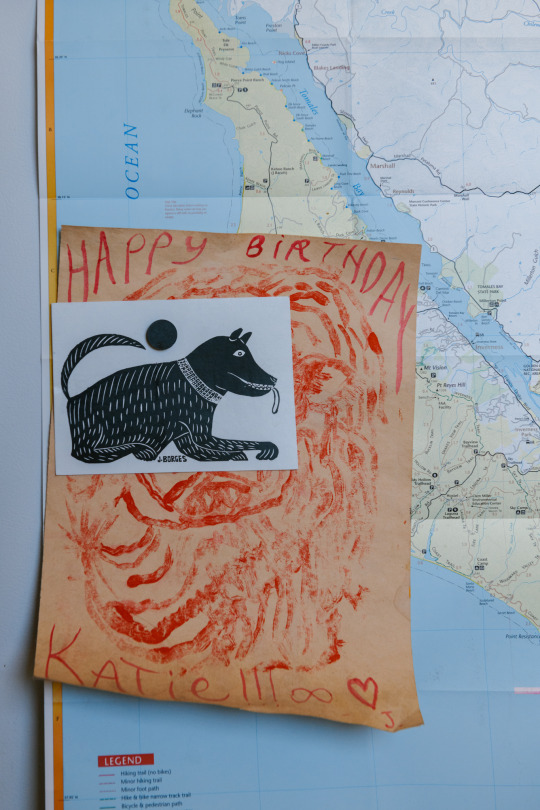

John Gnorski: I moved from the East Coast more or less on a whim in 2007, picking up and leaving the Hudson Valley, which had been my home for 6 years at that point, and ending up in Portland, OR. Luckily it was still a pretty affordable town at the time so I was able to piece together a nice existence doing carpentry for a day job (which would indelibly inform my art practice) and making art and music every other waking hour. I found a great community, fell in love with the truly epic landscape of the West, and at some point the West Coast just became home.

After many happy years up in Oregon, my partner Katie, who is a filmmaker, decided to get a master’s degree and that instigated our (truly auspicious) move to the Bay. One thing led to another, and we were lucky enough to find a house to rent in Pt. Reyes Station. Before long we found a great community out here and we hope to stay for as long as we can.

I do miss the East sometimes, especially the sort of archetypal procession of seasons there with crisp autumn days, deep winters, and summer thunderstorms and lighting bugs. That said, I can’t imagine a more beautiful place to live than here on the Northern California coast. I’m grateful every day to be here and I often think to myself how did I even end up here in this incredible place?

Studio AHEAD: Has Northern California come to influence the materiality of your work?

John Gnorski: Absolutely. In a very literal sense I tend to use native wood in my work whenever I can, but the influence goes beyond the physical material to a particular sensibility that seems to be shared by a lot of Northern California artists across generations and styles. I find that, at least in my experience, there’s less concern out here about the whole (false) binary of art vs. craft than I experienced as a young artist on the East Coast (particularly in the vicinity of New York).

I think that this attitude has, thankfully, changed quite a bit pretty much everywhere in the years since I moved west, but nevertheless California has a long history of breaking down established conventions and categories. Ceramics and wood sculpture, for instance, have been taken seriously out here for generations in a way that hasn’t historically been the case out east.

This anti-hierarchical spirit famously permeates a lot of the culture out here. A nice example is the great DIY building tradition of the “hippies” and other folks who took to the rural areas of the coast, starting in the middle of the last century, and made truly beautiful, strange, and inspired homes out here that flout both architectural convention and often the laws of physics. I’ve had the pleasure of helping to restore some buildings like this up in Mendocino and, to bring this full circle, some of the little scraps and bits I’ve taken with me from those projects have become pieces of my own work, along with the lessons of those often anonymous artist/builders who made, intentionally or not, amazing sculpture-houses.

There’s also a very strong Japanese influence on the aesthetics of so much California art/craft/design that’s found its way into my work. Would I be making these very Japanese/Noguchi-inspired lanterns if I hadn’t ended up here? I don’t know for sure but I’m guessing this place has informed them quite a bit.

Studio AHEAD: Don't get Homan started on Noguchi. He's obsessed. What is your relation to abstraction? Many of your sculptures and drawings almost seem to form recognizable figures, but not quite.

John Gnorski: With very few exceptions everything I make is representational even if it’s hard to decipher the image in the finished piece. I’m looking at a little watercolor painting right now that would almost certainly appear totally abstract to anyone but me, but I know that I made it in the Mojave desert and I can see the particular landscape that I was trying to depict—the horizon, the heat ripples, little constellations of scrubby desert plants—though it’s basically reduced to visual symbols.

It’s not necessarily a formal decision I’ve made to avoid pure abstraction, it’s more of a narrative one. Having concrete subject matter is an important starting point for me, one method of avoiding the potentially paralyzing experience of confronting the blank page. So even if the finished picture or object ends up miles away from where it began, I still start by saying to myself, for instance: I’m going to draw a lizard sunning itself on a stump or, as in one of the pictures I’m working on now, I’m going to draw a bather in Tomales Bay stooping down to look at a bat ray. One might end up a pretty faithful manifestation of the concept while another might go through the ringer of some process and turn out as a loopy line drawing that barely hints at its source material.

I sometimes do the same thing when I write songs, coming up with a title first and then writing into that. The two even intersect as in my continuing series of cloud pictures all of which are titled “Clouds Roll By Like A Train In The Sky” which is also the name of a song I wrote. Without the title those pictures read as geometric abstraction, but with the title they become clouds. Context is so important!

Studio AHEAD: Those cloud pictures, and also your Rorschach-like quarantine notebooks/bird and butterfly prints, give room to the subconscious. How do you get into that mental space when creating that allows for the subconscious to take over?

John Gnorski: Allowing room for the subconscious is really important to me because at the end of the day it’s very often the accidental/unintentional things that really resonate with me. To clarify, when I say subconscious in this context what I’m really talking about is allowing forces outside of my control to work in the picture/object. I try to maintain a decent level of competence when it comes to the basics of art-making, but I also try to use whatever “technique” I’ve developed to allow chance and accident to do their wonderful work. I know that nothing I could map out perfectly from start to finish will be nearly as interesting as something that transforms in ways I never could have anticipated through the process of the making.

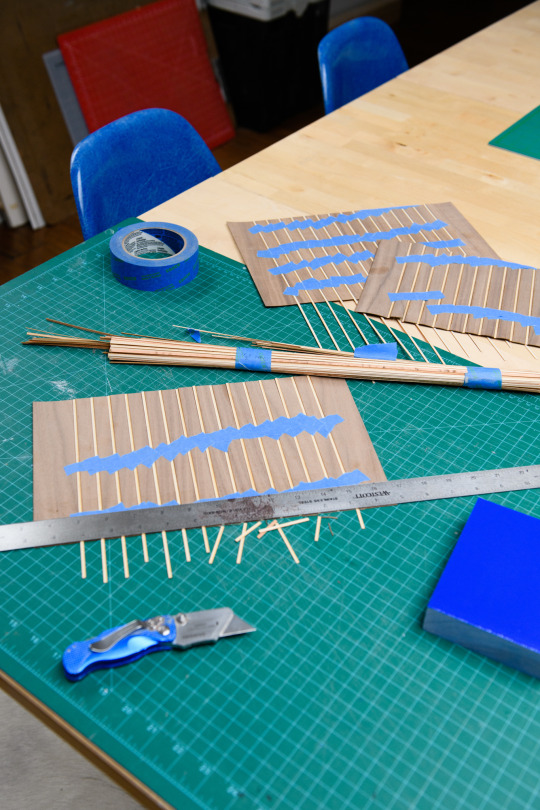

This sensibility is very visibly present in the Rorschach-style pieces and a lot of my sketchbooks and works on paper, but it’s there in less obvious ways in all of my work. The lanterns, for instance, might appear as though each little bit of joinery was carefully plotted out, but in reality they are built based on pretty simple line drawings and constructed in an organic manner. I’ll have a basic shape I want to achieve, but the way everything is put together is done on the fly. Sometimes a connection might become redundant structurally as a piece grows, but I’ll keep it in there as a remnant of the process. All the little false steps and unintentional gestures become a part of the piece and give it a complexity I wouldn’t have achieved if I’d set out with a dialed-in plan and done things in the most elegant and minimal way possible.

The same is true of the ink on paper pieces which begin life as charcoal drawings and allow chance to seep in throughout the process. I rub the drawings onto plywood “plates” which transfers them in an imperfect but legible manner. I’m also using multiple plates and pieces of paper to allow for misalignments, and the plates themselves are of a type of plywood that tends to have an active grain that sometimes splinters or “runs”—interrupting the carved line in often surprising ways. I hand print the plates, which produces unexpected textures, and then go back into the image with more ink or sometimes collage or pastel. So in the end what began as a pretty clear and maybe even graceful line drawing becomes, through the welcoming-in of chance, something a bit more nuanced and awkward, full of special little moments on its physical surface that come out of that totally not conscious place of process.

Studio AHEAD: Tell us about EARTH BABIES, your collaboration with Kate Bernstein. We are particularly interested in how collaboration impacts the creative process—we have many ideas about this at Studio AHEAD and those ideas are constantly evolving. Do you find it easier to work alone or with a partner?

John Gnorski: EARTH BABIES is the conceptual tent that shelters all the collaborative work that Katie and I do together. It started as a music/installation performance at an amazing event called Spaceness that friends of ours organized for 5 years on the coast of Washington at a place called the Sou’wester.

Spaceness was a very free-form community art-making event that revolved around the concept of the unknown, and often featured work relating to outer space or unexplored worlds. It was held annually in early spring—the very darkest and dreariest time of the year in the Pacific Northwest—and it featured music, dance, video, radio, you name it. Folks would work for months on their contributions, and it was so beautiful: community coming together to make their own entertainment and help each other through dark days. For me, this is the best case scenario for art-making. I like to think of it as subsistence art—art for fun and joy and also for survival. It honestly makes me tear up thinking about it, and I often cried during the performances there. It just moves me so much to see what people can make with little to no budget out of the simplest materials like cardboard, scrap wood, clip lights, fabric, words: whole worlds that can really put you under a spell, transport you, communicate a message, and make time and space for our imaginations to nourish one another.

Anyway (and forgive me, this is going to get maybe a little esoteric) Katie and I, inspired by a trip to Ghost Ranch in New Mexico, came up with this idea of a whole culture of beings living deep under the surface of our Earth called “Earth Babies.” We first wrote and recorded songs based on this imaginary world, and over the years we made various installations: the “Healing Machine” which was a sound bath in a hand-built A-frame in the woods and the “Hopler Archive,” a fictional natural history museum.

At this point, EARTH BABIES is the name we use whenever we want to make something creative without the burden of our “actual” identities getting in the way. It’s our shared alter ego that allows for maximum creative expression.

As for collaboration generally, as much as I love spending time alone in my studio, my ideal art making ratio would be 25% solitary practice, and 75% collaboration. I love the energy of working with other artists, performers, thinkers, etc., and I think that collaboration leads to amazing things no one ever could have come up with on their own. I also think that community events like DIY music shows, theater, potlucks and ephemeral art exhibits in informal spaces are the most heartfelt and wonderful forms of art —purely collaborative and collectively authored. Again, it’s that idea of “subsistence art”. If none of us had to worry about selling our work I think there would naturally be a lot less emphasis on individual style and a lot less concern about authorship. Maybe collaboration would be the new norm and we could all contribute a verse to the big song we sing to sustain ourselves.

Studio AHEAD: What's your favorite music to listen to while making art? You are also a DJ and musician.

John Gnorski: Katie and I host a radio show on West Marin’s community radio station KWMR every other Sunday morning, which has really made us feel connected to the community out here.

I listen to a huge variety of music in my studio from atmospheric/ambient music like Brian Eno and Hiroshi Yoshimura to soul to Neil Young to Terry Riley to Alice Coltrane to Lucinda Williams. I’ll often just rely on my cassette library to take a break from the digital realm, which features a lot of mixtapes from Mississippi Records, my favorite record store/label. But if I had to choose only one thing to listen to while making art it would be Ornette Coleman. I’ve listened to a collection of his recordings called Beauty Is A Rare Thing many thousands of times over the years in every studio, basement, garage, and shed I’ve worked in. His music has every color and emotion and gesture in it, and it radiates compassion and energy and love. It’s also difficult at times and can go from soothing to jarring pretty quickly, much like life. When I listen to a song like “I Heard It Over The Radio” I hear everything from voices harmonizing singing a folk song to animals making raucous calls to wind in the trees and rattling subway cars.

Studio AHEAD: What can you do in music that you can’t do in the plastic arts? And vice versa?

John Gnorski: For me the boundaries are pretty porous. As I alluded to earlier with the titling of my work, there’s a lot of crossover and dialogue between disciplines in my practice. It’s easier for me to come up with analogies. A skittering, hesitant line in a drawing conveys something similar to a thin, airy flute or a tentative phrase on a piano. Take a lyric like this one by Leonard Cohen:

Nancy was alone

looking at the late, late show

through a semi-precious stone.

It conjures all kinds of atmospheres and emotional states like a Rothko or an Alice Neel portrait. Whenever I hear Alice Coltrane play the harp I think of someone painting with absolutely every color on their palette.

Music, however—live music—does have the wonderful quality of being ephemeral that most plastic arts don’t possess. It allows you to really inhabit the moment if you choose to. As a performer you’re also able to collaborate with an audience in a way that’s much harder to do with visual art. If you can engage an audience, or are part of an engaged audience, it can really make the experience special, with everyone kind of rooting for the performers and contributing their attention and energy to make the whole experience really lovely.

Then I suppose there are some stories that can be more eloquently told in pictures or gestures than in sound. Light can be captured really evocatively in a drawing or a painting and used to make form in the realm of sculpture. There are some feelings you can only get, some ideas that can only be conveyed, when you’re in the presence of a physical thing.

Studio AHEAD: I want to end on the very first photo posted on your Instagram. It’s a poster that says: “Now is the time to do your life’s work.” How do you or how do you try to live this mantra?

John Gnorski: I made this picture as a kind of personal affirmation to hang on my studio wall many years ago. A lot of people who came through commented on it and it seemed like most everyone appreciated the reminder.

My idea of my “life’s work” changes all the time, but the constant is a commitment to making things that I hope will tell a story or convey a feeling clearly and with heart. At times it can seem like art is some kind of luxury or commodity, but then I remember how it has truly illuminated and influenced and given hope and shape to my life and the lives of a lot of other people over the entire course of human existence. I think that being an artist is as noble a vocation as any, and more helpful to humanity than a lot of things I could be doing with my time.

I’m in the fortunate position of being able to primarily make a living by making art and other art-adjacent objects these days, but in the recent past when I would be laboring away at a carpentry gig, I would think of that image and that mantra and remember that I had some kind of calling beyond the job that paid the bills—a “life’s work” that couldn’t be defined by an hourly rate—and that the artist work deserved and demanded my commitment. I still believe that if I show up for the muse or universe or whatever you want to call it everyday, ready and willing to work, that I’ll be able to somehow keep doing this as my life’s work and hopefully make things that help other people see life or hear it or survive and take joy in it.

Studio AHEAD: We love that. We always start with asking our clients how they live. It's so important. Can you give us three creative people/places/cultural forces based in Northern California that we should take note of?

John Gnorski: Cole Pulice is a musician/composer living in the East Bay whose music often keeps me company in the studio. We also listen to a piece of theirs almost every day on the short drive from our house to the trail that we walk to check on the animal neighbors and greet the day.

Bolinas/Pt.Reyes/Inverness DIY art/music scene This is an acknowledgement of the type of creative community vitality that to me is the heart of sustaining art-making—artists, musicians, writers—we can also get specific and talk about it in terms of two spaces where most of this stuff takes place: the Gospel Flat Farm Stand and the hardware store in Bolinas. Both are DIY spaces of the highest caliber that provide the setting and the energy for art to happen.

Ido Yoshimoto. I know that everyone reading this probably already knows Ido’s work [if not, we interviewed him here —SA] but I feel compelled to shout him out because he so generously invited me into the community here when we landed a few years back. He’s also shared knowledge and food and time. The people who make their lives here and share their talents and have profound respect for the land are the soul of this place, and Ido is one of those people.

Photos by Ekaterina Izmestieva

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Artist Spotlight: David Wilson

What kept popping up in our conversation with Oakland-based artist David Wilson was ways of seeing: landscapes, futures, memory. His watercolor series Facing the Other Way is a poetic rendering of the familiar (Mount Tam) made unfamiliar—and we encourage everyone with a love of Marin to spend some time with this remarkable piece and David’s equally remarkable comments (below) about how memory constructs these places we think we know so well.

If all of that is a little too conceptual for you, just know we met David at a dance party and that his art and artistic outlook is just as fun and wild as his DJ sets. To say nothing of the mind-meld that was "The Possible," about which: "I think my brain is just about healed, perhaps it’s time to try it again?"

Studio AHEAD: Hi, David! We want to start with a recent show of yours, “Framings.” It featured a large-scale drawing made of smaller drawings, all from the hillside of Wildcat Canyon, that you did daily over the course of several weeks. Tell us a little bit about this project, and maybe the role the parts play in the whole.

David Wilson: Hi! Yes, over the years of slowing growing into my drawing and painting practice, I’ve found it most rewarding to center the physical experience of sitting in the landscape drawing in direct observation, and to try to separate myself, as best I can, from the final results of what the image becomes. The way I do it, as you’ve noted, is by immersing myself in the parts, working on isolated daily pages that I carry out with me, continuing each day’s sitting with a new blank page picking up on the memory of where I left off.