#(it's probably because of how katakana handles foreign words)

Text

Using Other Languages in Prose

When a character speaks words from another language, it can be difficult to know how to represent that in the prose. Let's look at various ways of handling this.

The first thing is to figure out what language the narrator is theoretically speaking in. Say for example the book is written in English. The narrator could be a Chinese person, who only speaks Chinese. So then the conceit is that the entire book has been "translated" into English, so that the English reader can understand it.

If then a character in that story speaks Chinese, that too would be "translated" in the same way and end up as English text. Because that's how everything else Chinese is being handled within the book.

Now, what happens if a character speaks a language the narrator doesn't understand? How should that be handled?

Now a Spanish character appears and speaks in their native tongue. This is different from the language the narrator speaks, so it shouldn't simply be translated.

Ana waved and spoke excitedly in a foreign language, presumably Spanish.

You could write it like this, with the narrator not even quoting what was said, because they don't even know how to parse out the words.

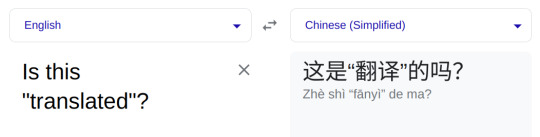

Correct (and incorrect?) translations provided by Google Translate. 😅

"¡Hola!" she called across the airport. "¡Es un placer conocerte finalmente!"

Or you could quote what was said entirely. If the language isn't the same as the translated language--in this case English--then it will still come across as being a different language.

In this case English and Spanish both use the Latin alphabet, so the reader can have some sense of what the dialogue sounds like, even if they don't understand what it means. They may even be able to guess at what some of it means, if there are words that are similar in their language.

If the language uses different characters--for example Japanese vs English--you could use the regular Japanese here.

"あなたの母はどこですか?" Hana said.

Though unless the reader can read that language, they won't be able to "hear" what the character says. But there are ways of writing that can still be phonetically sounded out by the reader, even if they don't understand the language.

For example, Japanese has "hiragana" and "katakana" characters which represent sounds, and can be used to sound out English words for Japanese readers. And we can use something called "romaji" to sound out Japanese words for English readers.

"Anata no haha wa dokodesu ka?" Hana said.

You may need to do something similar for things like complex names whose pronunciation is not easy to figure out from the spelling.

She laughed. "No no, my name is Siobhan. Say it with me--Shiv... awn."

Greg did his best to say it back to her.

Siobhan shrugged and clapped him on the shoulder. "Close enough I guess... Graaaig!" she said, saying his name strangely in jest.

Something else to remember is, if the reader can read that language themselves, they won't have the feeling of being unable to understand what was said, as the narrator or viewpoint character does.

So if you don't want to the reader to be able to understand the dialogue at all, just narrate that another language was spoken as before.

Another caveat is, if that other language is English--or whatever the book's language is for the reader--this wouldn't work at all. It would be assumed to spoken in Chinese, the same as everything else. In which case, it may be wiser to not quote the speech, and just narrate that they said something in another language.

If the speaker uses a mixture of a non-understood language and an understood language, you could separate them like this.

Shi looked bewildered. "I'm sorry, I don't speak Spanish."

"Oh lo siento mucho..." she said. "I've been practising my Mandarin, and then forgot to use it! How are you, Shi?"

Mark the other language using italics, for example. Or perhaps put the dialogue inside brackets?

Though, this would probably get quite confusing if English was used as this other language. Because you've got the "translated" book English, next to the not-translated English that the viewpoint character doesn't understand but is just in italics for some reason.

Not really sure what you could do in this case, but hopefully you'll be able to avoid such a situation in your writing? 😅

This is especially useful when a simple word is thrown in from their mother tongue.

"How long has it been, mi amigo?" Ana said, throwing her arms around him.

Here, it doesn't matter too much if the reader does or does not understand the Spanish--the main meaning of the dialogue is written in English. As in, the character said it in Chinese, which was then "translated" by the narrator for the benefit of the reader.

It can be tricky to talk about this stuff clearly, but when you read it in a book it can be fairly intuitive if done well--honest! 😅

Now what if the viewpoint character--Shi in this case--actually understands Spanish? How could you convey that?

Well it would be very confusing if it was simply "translated" by the book without comment. So what else could we do to indicate it's being spoken in a different language but Shi understands what was meant?

Let's rewrite an earlier example:

"¡Hola!" she called across the airport. "¡Es un placer conocerte finalmente!" (It's a pleasure to finally meet you!)

We could simply give the translation after the dialogue, as if the viewpoint character is adding an editorial note to help the reader out. Then we can mark that in some way--with brackets, or italics. Almost like having subtitles in a film!

However you do this, think about it like you're teaching the reader the rules of how your prose works. "Brackets means the translation of a piece of dialogue." If it's clear enough, they'll catch on pretty quick, and then follow along just fine. But if you use brackets for one thing, just be careful not to use it for other things as well or the rule won't be clear in their minds and intuitive.

In some situations you might even get away with showing something that hints at what was meant--the viewpoint character's thoughts, or something else.

"¡Hola!" she called across the airport. "¡Es un placer conocerte finalmente!"

"Nice to finally meet you too!" Shi replied in Chinese with a grin.

Ana laughed. "Oh lo siento mucho... I've been practising my Mandarin, and then forgot to use it! How are you, Shi?"

The fact he responded that way indicates that he understands what was said, and that Ana said something similar to "Nice to finally meet you."

The reader can pick up on things like that. But even if they don't, the meaning of what she said isn't vital to the story or anything, so that's probably fine.

This could be done in a different way though. You could simply outright say that the character is speaking in a different language.

"Hello!" she called across the airport, in Spanish. "It's lovely to finally meet you!"

So here the narrator is translating from this new language.

Characters could even be conducting a whole conversation in the other language. But you probably don't want to say over and over again "She said this in Spanish, then he said that in Spanish..."

Shi shifted to Spanish too. He'd been practising, and looked forward to speaking to Ana in her own tongue!

"He- Hello? Ana," he said, sheepishly.

Ana beamed at him.

Shi chuckled, and muddled through another sentence. "My... name is... Shi!"

You could have whole scenes where everyone is mainly speaking Spanish, using this method. Even whole chapters, perhaps! Just remember to let the reader know if you go back into Chinese or any other language. You may want to give them a little reminder here and there too, of what mode they're currently in so they don't get confused.

0 notes

Text

Maijo posted more Jorge-related stuff on twitter! It’s mostly some early notes and character concept art for the novel.

Highlights:

1) In early concept stage, 37th Universe’s Bruno’s stand was called either The Quilt or The Quiet (Maijo’s handwriting still eludes me), while Mista’s was Cool Runnings (would it be a tiny bobsleigh team?). Fugo’s Stand is never named in the novel, but it’s Scarface.

2) The “Sudden Jorge Joestar Digression”, in which we learn that detective Jorge’s wacky hair is supposed to be a star! His pose here is also a star. Maijo’s note vaguely implies that Jorge might have subconsciously chosen his hairstyle because of his feelings around not having the star birthmark. Jorge’s response is like “I JUST HAVE UNRULY HAIR, SHUDDUP”; seems the comment touched a nerve. (And in the bottom right is a prime example of Maijo portraying himself as Togo from ID:INVADED, talking about how it’s been so many years since he wrote the book)

3) You’ve heard of JORKER, now get ready for

JORGE JOERTAR

#jorge joestar#jorge tag#maijo and jdc stuff#when you and your writer senpai are so similar you even make the same kind of typos in book titles#(it's probably because of how katakana handles foreign words)

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 1 (17): the Utensils for the Small Room.

17) With respect to the utensils for the small room, it is better if everything is [somewhat] lacking¹. There are people who detest things that are even slightly damaged², [but] this [kind of attitude] is completely unacceptable.

In the case of newly-fired [pieces of pottery] and objects of that sort³, if they have developed cracks⁴, they are difficult to use⁵. But things like imported chaire and other “proper” utensils⁶, when they have been repaired with lacquer⁷, can still be used in the future.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Besides this, when [we] speak of the way to combine the utensils⁸: a recently fired chawan [used together with] an imported chaire -- [you] must know how to do [things] like this⁹.

In Shukō's period, even though the things [used for chanoyu] were still splendid¹⁰ at that time, he put his treasured ido-chawan¹¹ into a fukuro, handling it just like a temmoku¹²; and [he] initiated the practice of always bringing out a natsume¹³, or a recently-made chaire, together with it¹⁴.

_________________________

◎ The chawan known as the Kanamori ido [金森井戸本] and the Honnō-ji bunrin [本能寺文琳] chaire. Two examples of damaged utensils that continued to be used for chanoyu in the small room after they were repaired with lacquer.

¹Yorozu-koto taranu ga yoshi [よろず事たらぬがよし].

The auxiliary verb taru [たる] means “is enough;” “is sufficient.” Taranu [たらぬ], then, means “not enough;” “insufficient.”

²Sonji [損し].

Sonji [損じ] means injured, damaged, cracked, defective.

³Ima-yaki nado [今やきなど].

Ima-yaki [今燒] means pottery that has been fired recently. Nado [など] means “(and) things of that sort.”

Recently made things are “difficult to use” if they have become damaged (through misuse -- whether because of carelessness or otherwise) because they can easily be replaced: so using them seems inauspicious (or niggardly).

⁴Ware-hibi kitaru ha [われひゞきたるハ].

Ware-hibi [割れ罅] means to crack or split through use (it does not refer to the natural crackles that are present in certain glazes).

Kitaru [來る] means to develop, be due to (literally, “to come,” “to arrive”). In other words, damage that has come about after the piece was in the host's possession, due to improper handling (whether accidental or through negligence is not important).

⁵Mochii-gatashi [用ひがたし].

Mochii-gatashi [用い難し] means something is difficult to use, difficult to make use of.

⁶Kara-no-chaire nado-yō no shikarubeki-dōgu ha [唐の茶入などやうのしかるべき道具ハ].

Kara-no-chaire [唐の茶入] means a chaire that was imported from the continent (kara [唐] means Tang China, though none of the chaire were made before the Southern Sung period, and most long afterward; the word kara, though more commonly when it was written phonetically, was also used to mean Korea in pre-modern times).

Shikarubeki-dōgu [然るべき道具]: shikarubeki [然るべき] means proper, appropriate.

This refers to objects that were “real” utensils, on account of their pedigree and history of transmission*. Comprehending this statement on a “gut level” depends on an attitude that we -- surrounded by imitations (while the originals are almost unknown, and certainly unapproachable; not a part of our reality or experience) -- are not really able to assume.

___________

*In contrast to things that the host found (or made) by himself.

⁷Urushi-tsugi shite [うるしつぎしても].

Urushi-tsugi [漆繼ぎ] means something like “repaired with lacquer.” Urushi-tsugi suru [漆継ぎする] means “to stick something together with lacquer.”

In the period when Nambō Sōkei wrote down these entries, there was no such thing as kin-tsugi [金継ぎ], where the lacquer-repair is sprinkled with gold powder as it is drying. In his time, the person undertaking the repair work usually tried very hard to approximate the original color of the piece as closely as possible, so that the damage would be (almost) undetectable. Which did not mean that people tried to pass such things off as being in perfect condition: famous utensils were known, as was any damage that befell them; the purpose was to make them usable again, with as little distraction* and as possible.

Between Sōkei's day and the appearance of kin-tsugi in the Edo period, there was a time when such repair work was done in a more perfunctory manner, using ordinary black lacquer. Here the idea was simply to mend the damage, without bothering to try to obscure it, let alone enhance it (by adding gold). This was the most wabi sort of repair†.

___________

*People worried that the piece would come apart while they were using it, which unsettled the guests as well as the host. This is why the effort was made to efface the damage to the extent that it did not catch the attention of the conscious mind.

†The vertical cracks on the front side of the Kanamori ido (shown above, in the text of the entry) were repaired in this way.

This is possible to do because lacquer -- unlike most paints -- does not change its volume (through evaporation of the solvent) as it dries. Thus the dried lacquer occupies precisely the same area as it did when it was wet, and it is this that allows it to form a water-tight seal.

⁸Dōgu no tori-awase to mōsu ha [道具ノ取合ト申スハ].

Tori-awase [取り合わせ] means the way to combine the utensils together to produce a pleasing effect.

The sudden shift from using hiragana to using katakana for the remainder of this entry (which is why I inserted the dashed line, to separate the text of the first part of this entry from this) suggests that this was originally a separate topic that Jitsuzan either conflated with the text (on using damaged and repaired utensils) that went before, or that was inserted into this place (by someone else), with the intention of introducing certain ideas that seem to be foreign to the period in which Nambō Sōkei wrote these memoranda -- but closely connected with early Edo sensibilities (or, perhaps, attitudes that chajin were being advised to adopt during that period). The rule that is being laid out -- and, even more, the example that is used to illustrate that rule -- is an oddity, a non sequitur not only to what has gone before (in this entry), but also to the kinds of teachings expounded more generally in the Nampō Roku.

⁹Gotoshi kokoroe-beshi [��此心得べし].

Gotoshi [如此 = 如し] means like, as if, the same as, in the same way.

Kokoroe [心得] means to know, understand. -Beshi [べし] means should (do something).

Prior to Rikyū, people involved with chanoyu tended to feel that all of the utensils used during a given chakai should be of similar quality (all costly antiques, or all new), and that the host should always make an effort to use the best utensils that he could afford*. (And many modern schools also hold this to be true even today -- a legacy of the damnatio memoriae that was imposed on Rikyū following his seppuku.) People of means amassed a modest collection of expensive utensils†, while the hermits and recluses who pursued chanoyu as a method of Zen training used worthless things that they discovered here and there.

But what this passage is advocating is that the host not be afraid to combine a newly made piece with an estimable and renowned utensil -- not to contrast their values, but because they combine in a pleasing way that is appropriate to the setting and circumstances of the gathering. In other words, be content and use the things you own, rather than covet objects that are beyond your means.

___________

*Since only one representative example of each of the necessary utensils was all that was required.

†Because the “goal” was always to use the finest utensils that the host could afford, people tended to continually upgrade their collection, replacing their former treasures with new ones (while passing on the old pieces to other people whose collections were yet at a lower level).

A comment should be made regarding Ashikaga Yoshimasa and his huge collection of cha-dōgu. Prior to the destruction of his storehouse -- which was apparently a political statement, rather than one motivated by avarice -- Yoshimasa had access to a great collection of largely imported pieces of art. However, these were not his personal possessions. Rather, the collection represented the tribute that had been paid to the Ashikaga family over the years (though this “tribute” was called by different names, depending on the circumstances under which the object had been gifted to the government), and he had access to it simply because he was the shōgun (and then the de facto regent during the rule of his immature successor). The dōbō [同朋], who appear to have been descended from functionaries in the Koryeo court, were employed primarily to sort through the contents of the official storehouses, appraising the worth (or lack whereof) of each object stored (since there appear to have been almost as many worthless pieces in storage as there were authentic treasures). Noticing that certain of these objects were suitable for use in chanoyu, these things were brought to Yoshimasa’s attention because he had shown an interest in chanoyu, and the dōbō Nōami then instructed Yoshimasa in their use.

Thus, in a sense, this was all an experiment in seeing how many variations on the theme of chanoyu were possible with the objects found in the storehouses, rather than an exercise in collecting and flaunting his wealth.

¹⁰Imada mono-goto kekkai ari-shida ni [イマダ物ゴト結構ニアリシダニ].

Imada [未だ] means as yet, still, only.

Mono-goto [物事] means things, everything (i.e., the arrangements and the utensils employed for chanoyu).

Kekkō [結構] means splendid, nice, wonderful, excellent.

¹¹Hizō no ido-chawan [秘蔵ノ井土茶盌].

Hizō [秘蔵] means to treasure, prize, cherish.

Ido-chawan [井土茶盌] is usually written ido-chawan [井戸茶碗] today.

While it is true that Shukō owned an ido chawan (the bowl that is now known as the Tsutsu-i-zutsu [筒井筒]), there appears to be a distinctly Edo period flavor to this story -- since Shukō most probably used his ido-chawan as a kae-chawan, as was the convention at that time*.

It is extremely difficult to sort out the stories related to these early chajin, if only because of the deliberate distortions and conflations inflicted on history by Kanamori Sōwa. It appears, however, that Shukō arrived in Japan as a refugee, and he may have had very few utensils during the first years of his life in Japan -- and likely used whatever he could at that time. But there was obviously something special about this man, suggesting that he had already established a reputation as a master of chanoyu while still on the continent, and over time, as his finances (and social position) improved, he began to acquire utensils that were more and more suitable.

Ido-chawan -- bowls with a high foot -- were (originally) made to be used (in Korea) by the lower classes, when making offerings to the dead, or during the indigenous Ancestor Worship ceremonies. So placing such a bowl in a cloth bag† and handling it formally on such an occasion certainly would have been appropriate (even if it would also indicate -- if the ido-chawan was truly the only bowl that he used -- that Shukō was of a somewhat lower social class than is generally assumed). But it is the apparent surprise over this kind of handling -- which clearly originated in the mind of an Edo period commentator who was ignorant of these foreign customs -- that smacks strongly of anachronism‡.

The same can be said of the statement (see the next footnote) that Shukō regularly used a natsume with this chawan -- which also illuminates a distinctly Edo period sort of sensibility**. This all, in turn, suggests that at least part of this section of the entry is likely spurious, perhaps added (as an illustration or encouragement?) by someone intent on making a certain kind of statement, or establishing a precedent for a certain kind of behavior. It is possible that Jitsuzan did this, though it is more likely that this material was added by the same person who inserted the Kanamori Sōwa version of chanoyu history into the third entry.

___________

*The kae-chawan was not usually used to serve tea. The exception to this rule, however, being when a nobleman-guest was accompanied by attendants, and he asked the host to serve them tea as well. In the early days, since tea was exceptionally rare and precious (so the host would usually grind only enough to serve the single guest -- this is why the tiny ko-tsubo chaire were preferred as the tea containers at that time), “serving them tea” usually meant that the tea remaining in the chawan after the nobleman had drunk (the cha-no-ato [茶の跡]) was diluted with some more hot water, and this koicha-hot water mixture was then poured into the kae-chawan, and offered to the attendants (who shared the bowl of usucha by passing the kae-chawan around among themselves).

It seems that the occasion when Shukō offered the guests tea in his ido-chawan took place shortly after his arrival in Japan, apparently while performing a memorial service for his teacher -- who had either been killed during the persecution of the Amidaists in Korea beginning in the second half of the fifteenth century (which precipitated Shukō’s own exodus from his homeland), or perhaps had lost his life during the dangerous voyage of escape to the Korean expatriate communities (Sakai and Hakata) in Japan.

In fact, if Shukō owned both a temmoku-chawan and an ido-chawan on the occasion of that famous memorial service (as seems likely -- if he truly did not have a temmoku, then it is difficult to imagine that he would have gained the respect of his contemporaries for his practice of chanoyu), it is probable that he prepared the tea and made the offering using his temmoku-chawan. And then, after taking the temmoku down from the altar, a little hot water would have been added to the temmoku and the koicha-hot water mix was then poured into the ido-chawan, and the ido-chawan containing something resembling thin usucha was then passed around for the (two or three) guests, as well as the host, to share. This is how the nobleman-shōkyaku’s attendants were usually served -- and doing so on this occasion would mean that the deceased master was the true guest, while all those present were merely his attendants (an especially apt way of viewing things: in a similar vein, passing the chawan around after making the offering, so that each person present could drink a little of the tea -- as a sort of way to come into communion with the deceased -- would have been similar to the practice of drinking of some of the shira-zake [白酒] that has been offered to the family’s Ancestral Spirits, a custom that persists in modern-day Korea).

†In the early days, utensils did not have boxes (a few of the early karamono chaire had ivory or lacquered wooden hikiya [挽家], but this was by and large the exception rather than the rule). Boxes first appeared in the late sixteenth or early seventeenth centuries, for chaire (the earliest examples suggest that these boxes were originally made as hitotsu-iri sa-tsū-bako [一入茶通箱], boxes for a single container of gift tea; and, when the boxes were of high quality, they were later reused by the host as storage containers for his own chaire).

Traditionally, treasured utensils were provided with cloth bags, to keep them reasonably dust free when not in use. This practice began to fall out of favor during Rikyū’s period of influence, since he disliked displaying anything but the chaire in its bag (considering that the old cloth bags made the chawan dirty, from accumulated dust that fell into the bowl prior to the bag’s being removed at the beginning of the temae). Thus, when speaking of Shukō’s period, it is hardly surprising (and certainly not exceptional) that his ido-chawan was provided with a cloth bag -- even if this struck the Edo period reader as being unusual.

‡If Shukō used his ido-chawan to prepare tea (because he did not own a temmoku-chawan at that time), it was most likely done only until he had the means to acquire a temmoku, since he is eventually recorded as having served tea to other people using a temmoku-chawan on a dai on ordinary occasions. (This temmoku-chawan is often shown resting on a Chinese tsui-koku temmoku-dai [堆黒天目臺] in modern publications, but this is anachronistic since this temmoku-dai seems to have come to Japan in the Edo period. Shukō would have used a plain black Chinese dai, most likely one of the 36 meibutsu kazu-no-dai [数の臺], though the specific dai has apparently not been identified by scholars.)

It should be pointed out that, following the dissolution of the Koryeo court, chanoyu began to spread out among the different ranks of Korean society, and it was at this time that the foundations for the different kinds of practice (including the thread that we would identify as wabi no chanoyu -- which rejected the use of the temmoku in favor of locally made bowls that were not placed on a dai) began to appear.

What we can say with reasonable confidence is that Shukō lived in Japan for between 30 and 40 years, following his arrival from the continent (which seems to have been during the 1460s), and that he practiced chanoyu for that whole time; that he owned both a temmoku chawan and an ido-chawan (both of which are shown above), as well as a second large chawan (known as the Shukō chawan -- it was destroyed in the fire that consumed the Honno-ji following Nobunaga’s seppuku); and that, according to the story (which has been circulated since the early sixteenth century -- and possibly even earlier, during Shukō’s own lifetime), on one occasion he passed around the ido-chawan for the guests to share (which was significant since it was the actual guests who drank from the bowl, not their lower-ranked attendants). How these points have been interpreted after the fact, then, depends on who is doing the interpreting -- and his reasons for wanting to do so.

◎ Above is a photograph of Uesugi Kenshin’s [上杉謙信; 1530 ~ 1578] collection of tea utensils, which he kept in the lacquered box shown behind the other pieces. Kenshin was a daimyō, and one of Jōō’s chief disciples. He also seems to have been a follower of the Ikkō Shū [一向宗], the Amidaist Sect of Buddhism closely connected with the early chajin (and from the teachings of which much of the early philosophy of chanoyu was derived). Kenshin retired around 1553, and spent the remainder of his life practicing chanoyu and writing a commentary on Jōō’s Chanoyu Sanbyak’ka Jō [茶湯三百箇條] (the Three Hundred Lines of Chanoyu). What is important about this photo is that, with the exception of his kama and mizusashi, it shows the entire utensil collection of a man seriously devoted to the practice of chanoyu in the middle of the sixteenth century. The reader is asked to take note of the two ordinary chawan (both of Seto ware, the smaller one brown, and the other white), and how shallow they are. Thus Jōō spoke of the ido-chawan as being “deep” in his collection of the Hundred Poems of Chanoyu. (The objects shown in front of the carrying box are, from left to right, a smaller brown Seto chawan [瀬戸天目茶碗] -- “Seto temmoku” referring to the glaze, not the shape or how the chawan was used --, a chasen [茶筅], an ivory chashaku [象牙茶杓], a Seto kake-hanaire [瀬戸掛花入], a larger white Seto chawan [白瀬戸茶碗], a Chinese yu-teki temmoku [油滴天目], a shin-nakatsugi [眞中次], a bronze oki-hanaire [唐金置き花入], a maki-e temmoku-dai [蒔絵天目臺] -- probably of Japanese make --, and the cloth bag for the nakatsugi.)

**This section of this entry clearly deals with the idea of tori-awase, but the concept of tori-awase (as the word is used here) did not begin to appear until near the end of Rikyū’s lifetime (specifically, after he entered Hideyoshi’s household), as a consequence of the concatenation of the very recent idea (originated, many say, by Furuta Sōshitsu) of producing utensils specifically for use in chanoyu, coupled with Rikyū’s sudden access to Hideyoshi’s large collection of tea utensils (which he was encouraged by Hideyoshi to use for various -- often political -- reasons: this is why I included the photo of Uesugi Kenshin’s collection of tea utensils above, since these are the things that he used every time he served tea, with the use of the temmoku being linked to the rank of the guests, while the two ordinary bowls allowed him to employ kasane-chawan if there were many people to serve). Only then, when a large number of things of different types suddenly were available to the host at the same time, and (outside of Rikyū’s personal situation) for a reasonable cost (pieces of pottery were generally sold based on size at this time, and since most tea things are small, their prices -- at the outset -- were very low), could people begin to acquire several examples of each of the required utensils, and so begin to pick and choose -- and then devise “rules” governing what was suitable on different occasions, according to the weather and the guests being entertained.

In Shukō’s day, people assembled a single set of utensils, which contained one of each of the necessary things, so the idea of “tori-awase” (if they even used a name for the concept) could only guided their purchases; it was not a thought process that was employed when deciding which utensils to use when serving tea to people on any given occasion (if you have only one of each of the necessary utensils, then that is what you use). And this remained the usual state of things well into the sixteenth century.

When Shukō used a shin-nakatsugi or a recently-made chaire -- or a large karamono katatsuki or a precious ko-tsubo -- he did so because those were the only utensils he owned at that time. And as his finances improved (and as more and more of his contemporaries died without leaving heirs who were interested in practicing chanoyu, resulting in their collection of utensils being put up for sale), he was able to acquire successively better things. But as these new utensils entered his collection, the old things were given away or sold, rather than hoarded.

¹²Temmoku dōzen ni ashiwaruru ni ha [天目同前ニアシラハルヽニハ].

There is an odd feeling in the narrative here. Ido-chawan were certainly “inferior” to the temmoku bowls, but they were really not competitors for the same purpose in the system. Originally, while the temmoku (as “small chawan”) were used to prepare and serve the tea, the ido bowls were used as kae-chawan (the “large” chawan in which the chakin and chasen were carried into the room, and in which the chasen was cleaned at the end of the temae). Their functions were not interchangeable*.

Asserting that Shukō handled his the ido-chawan like a temmoku seems to be a misunderstanding of what Shukō actually did -- as discussed in sub-note “*” under the previous footnote.

Sometime between Shukō’s death and Jōō’s period a sort of wabi transformation did begin to occur†, where the pieces that had been neglected (for example, the bowls that had been used as kae-chawan) began to be used as main utensils, while the subsidiary positions were filled by newly-made pieces. But it is very unlikely that the change occurred any earlier than the early to middle sixteenth century.

___________

*Even when, as occasionally happened, the ido-chawan was used to serve tea, it was tea that was to be offered to the nobleman-guest’s attendants that was put into the ido-chawan -- people whose rank put them below consideration of the use of a temmoku -- never to the nobleman himself.

†Perhaps as the disparate threads of gokushin practice and wabi no chanoyu began to sort themselves out.

¹³Kanarazu natsume ・ ima-yaki nado no chaire [カナラズナツメ・今燒ナドノ茶入].

Kanarazu [必ず] means constantly, always.

However, there are several major difficulties with the narrative here:

- the natsume is said to have been created by Jōō (Rikyū states this several times in his writings), while Shukō is credited with creating the shin-nakatsugi, thus Shuko could not have used a natsume (Jōō was born the year that Shukō died); and,

- there were no such things as “ima-yaki chaire” -- in the sense of the word as it was used by Rikyū and Sōkei -- in Shukō’s day.

During Shukō’s lifetime (he died in 1502), chaire were not being made commercially -- there were no tea utensil shops in the marketplace comparable to what we know today (these kinds of firms came into existence in the Edo period). Potters traditionally focused on making things used in daily life, and starting to make pieces specifically for use in chanoyu (that were sold in the pottery market) only during the last couple of decades of Rikyū’s lifetime.

In the fifteenth century, if someone wanted to buy a newly made chaire, it had to be specially ordered from the potter (usually through direct consultation with the potter, with the purchaser explaining the details of the size and shape of the piece that he wanted); and while the cost might not have been very high (since the prices seem to have been based on the amount of space that each pot took up in the kiln), getting one required considerable effort (and probably a wait of up to a year or more, since most kilns were only fired at certain times of the year). People used contemporary chaire not because they were inexpensive alternatives to the imported pieces, but because that was all they could get (since trade with the continent had come to a stop in the fifteenth century, and most of the expatriate chajin -- who constituted the vast majority of practitioners in that period -- had escaped from the continent without the luxury of bringing their utensil collection, or their money, with them). Because these chaire were ordered by experienced chajin, the early Japanese-made pieces were similar enough with the continental originals that they were considered to be essentially their equals (such made-on-demand chaire had first appeared in Korea early in the fifteenth century) -- according to Rikyū -- and were to be handled in the same manner. Thus the condescension toward locally produced pieces expressed in this entry is anachronistic.

In Rikyū’s day, newly fired chawan were viewed in something resembling this manner because they were made to order, and easy to obtain (some of this has to do with the fact that when chawan became dirty, they were replaced: this had been the practice since antiquity, and the reason why chawan were always inferior to chaire -- which, like the cha-tsubo, were considered to improve the longer they were used). But newly made chaire were still acceptable, and perfectly suitable for use in chanoyu, though they were not held in the esteem accorded the earlier pieces (whether imported from the continent or made in Japan).

Using natsume as a general word for all lacquered tea containers (assuming that whomever wrote this knew that Shukō was actually associated with the shin-nakatsugi, rather than the natsume) was another convention that arose during the Edo period.

¹⁴Dasare-shi to nari [出サレシトナリ].

Dasare-suru [出されする] means to bring something out (for the first time), to start doing something.

In other words, while his contemporaries were still restricting themselves to elegant arrangements, Shukō started doing things differently -- by using distinctly wabi utensils during his service of tea.

The way this is written suggests a total ignorance with the actual historical development of wabi-no-chanoyu, and it is hard to accept that Nambō Sōkei would have been guilty of such anachronistic sentiments.

2 notes

·

View notes