#And then you're expected to work out for yourself which bits you can extrapolate and assume were true outwith England

Text

Alright uninformed rant time. It kind of bugs me that, when studying the Middle Ages, specifically in western Europe, it doesn’t seem to be a pre-requisite that you have to take some kind of “Basics of Mediaeval Catholic Doctrine in Everyday Practise” class.

Obviously you can’t cover everything- we don’t necessarily need to understand the ins and outs of obscure theological arguments (just as your average mediaeval churchgoer probably didn’t need to), or the inner workings of the Great Schism(s), nor how apparently simple theological disputes could be influenced by political and social factors, and of course the Official Line From The Vatican has changed over the centuries (which is why I’ve seen even modern Catholics getting mixed up about something that happened eight centuries ago). And naturally there are going to be misconceptions no matter how much you try to clarify things for people, and regional/class/temporal variations on how people’s actual everyday beliefs were influenced by the church’s rules.

But it would help if historians studying the Middle Ages, especially western Christendom, were all given a broadly similar training in a) what the official doctrine was at various points on certain important issues and b) how this might translate to what the average layman believed. Because it feels like you’re supposed to pick that up as you go along and even where there are books on the subject they’re not always entirely reliable either (for example, people citing books about how things worked specifically in England to apply to the whole of Europe) and you can’t ask a book a question if you’re confused about any particular point.

I mean I don’t expect to be spoonfed but somehow I don’t think that I’m supposed to accumulate a half-assed religious education from, say, a 15th century nobleman who was probably more interested in translating chivalric romances and rebelling against the Crown than religion; an angry 16th century Protestant; a 12th century nun from some forgotten valley in the Alps; some footnotes spread out over half a dozen modern political histories of Scotland; and an episode of ‘In Our Time’ from 2009.

But equally if you’re not a specialist in church history or theology, I’m not sure that it’s necessary to probe the murky depths of every minor theological point ever, and once you’ve started where does it end?

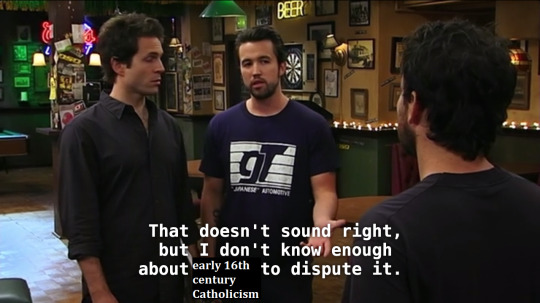

Anyway this entirely uninformed rant brought to you by my encounter with a sixteenth century bishop who was supposedly writing a completely orthodox book to re-evangelise his flock and tempt them away from Protestantism, but who described the baptismal rite in a way that sounds decidedly sketchy, if not heretical. And rather than being able to engage with the text properly and get what I needed from it, I was instead left sitting there like:

And frankly I didn’t have the time to go down the rabbit hole that would inevitably open up if I tried to find out

#This is a problem which is magnified in Britain I think as we also have to deal with the Hangover from Protestantism#As seen even in some folk who were raised Catholic but still imbibed certain ideas about the Middle Ages from culturally Protestant schools#And it isn't helped when we're hit with all these popular history tv documentaries#If I have to see one more person whose speciality is writing sensational paperbacks about Henry VIII's court#Being asked to explain for the British public What The Pope Thought I shall scream#Which is not even getting into some of England's super special common law get out clauses#Though having recently listened to some stuff in French I'm beginning to think misconceptions are not limited to Great Britain#Anyway I did take some realy interesting classes at uni on things like marriage and religious orders and so on#But it was definitely patchy and I definitely do not have a good handle on how it all basically hung together#As evidenced by the fact that I've probably made a tonne of mistakes in this post#Books aren't entirely helpful though because you can't ask them questions and sometimes the author is just plain wrong#I mean I will take book recommendations but they are not entirely helpful; and we also haven't all read the same stuff#So one person's idea of what the basics of being baptised involved are going to radically differ from another's based on what they read#Which if you are primarily a political historian interested in the Hundred Years' War doesn't seem important eonugh to quibble over#But it would help if everyone was given some kind of similar introductory training and then they could probe further if needed/wanted#So that one historian's elementary mistake about baptism doesn't affect generations of specialists in the Hundred Years' War#Because they have enough basic knowledge to know that they can just discount that tiny irrelevant bit#This is why seminars are important folks you get to ASK QUESTIONS AND FIGURE OUT BITS YOU DON'T UNDERSTAND#And as I say there is a bit of a habit in this country of producing books about say religion in mediaeval England#And then you're expected to work out for yourself which bits you can extrapolate and assume were true outwith England#Or France or Scotland or wherever it may be though the English and the French are particularly bad for assuming#that whatever was true for them was obviously true for everyone else so why should they specify that they're only talking about France#Alright rant over#Beginning to come to the conclusion that nobody knows how Christianity works but would like certain historians to stop pretending they do#Edit: I sort of made up the examples of the historical people who gave me my religious education above#But I'm now enamoured with the idea of who actually did give me my weird ideas about mediaeval Catholicism#Who were my historical godparents so to speak#Do I have an idea of mediaeval religion that was jointly shaped by some professor from the 1970s and a 6th century saint?#Does Cardinal Campeggio know he's responsible for some much later human being's catechism?#Fake examples again but I'm going to be thinking about that today

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

ἰδέα

Dear Caroline:

This was very illuminating, but as you say, not that surprising. My naive Venn Diagram for EA sees it as the intersection of Behavioral Economics and Utilitarian Philosophy (alternatively, it could also be portrayed as the friendly, charity-focused front of the Rationalist movement), so your economics background would clearly predispose you to it at least partially. Beyond that, I get the feel that Consequentialism is the philosophy of choice amongst economists: it goes well with a positive evaluation of capitalism, expected value calculations and 'the most good for the biggest number'.

More intriguing is what you say about 'taking ideas seriously', which requires a certain type of mentality - very intellectual, very logical, a bit self-centered, and not too pragmatic or accommodating. I suspected, probably wrongly and extrapolating badly from myself, that teenagers would go along this a lot, the context being them still retaining black-and-white mind frames while having lost their religious beliefs. It definitely did with me, and the danger here is that any reasonably good and plausible memeplex that you pick up has the power to latch on to you like barnacles to a rock; you are very unlikely to go and read other visions and counterarguments, and it will take you ages to purge yourself of dogmatic beliefs.

But by taking ideas seriously I think you mean not only questions of belief and acting out, but of exploring the logical consequences and paths they lead to. I see this making a lot of sentence when you're talking of logic and mathematics, where you can follow the thread of theorems derived from the axioms, and check for contradiction or unlikeable results. I kind of don't see it working that well in real life, though, because of the massive degree of uncertainty, and the way in which a lot of what you'd call Bayesian inference just feels like cooking up bs numbers without sufficient evidence, or even the perspective of having it. The AI risks debate has flared up quite a lot since you wrote this post. I will be reading a couple of books on the topic next year, but it is difficult not to feel two vibes about it which lead to -in cases of doubt- to some degree of flippancy:

AGI doom scenarios look such a distillation of sci-fi uber-nerd cultish, dystopian fantasies that it feels difficult to even start to take them seriously

Then again, lots of people I consider really smart do take them seriously, including some that seem to have started from the opposite side of the fence. But heck, they can all still be nerd-biased one kind or another. And it is all ultimately a castle built on speculations and what ifs.

Quote:

To take ideas seriously means that you intend to live by, to��practice, any idea you accept as true.

Ayn Rand

0 notes

Note

Genuine question: do you have any tips for sci-fi worldbuilding? I always seem to zoom in too far; that is, I'm really good at little details but big picture is often hard for me, so my universes often feel a little empty.

I'm not a very good writer but I'll try to answer the best I can.

I think ultimately what sells worldbuilding is presentation: it's much better to conceal than to reveal. When you're coming up with a setting you'll probably end up with copious notes on the history of the world, the relationships between characters and factions, the physics, metaphysics, and (possibly) magic systems of the universe. This is stuff you need to know for the setting to maintain its own internal logic. However, much/most of this does not need to be explicitly told to the reader. Two reasons for this:

1) When you allow the reader to fill in the blanks with their imagination, they become more involved in the story and you can play with their expectations later on. In the mind of the reader, the world you've created becomes larger than what you've actually written

2) Suspension of disbelief. When you supply the precise rules for how magic or an FTL drive works, the reader might say: “that couldn’t work” or “what about all these implications that are never addressed?” Examples: old-timey sci-fi featuring outmoded or incorrect physical theories as central plot points or Harry Potter magic where you “can’t make food” but you sure as hell can turn inanimate objects into animals that could then be eaten. If instead of saying “Here’s how FTL travel works” you show people interacting with teleportation devices that have just a hint of underlying logic to them- well that’s just a bit more palatable (and harder for the reader to find plot holes). Read Gene Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun series and the bits about the Mirrors of Father Inire for a real good example of this.

This (to my understanding) is what they mean when they say “show, don’t tell.” When you reveal a world through character dialogue, fragments of in-universe writing, descriptions of settings as seen through the eyes of people who inhabit them- it’s much more organic and engaging than descriptive monologues on history and politics from an impartial narrator.

So back to your point about “little details”- I actually think this is a great place to start when worldbuilding. In my opinion, the little details of a world are the most interesting bits. You can imply a lot with a little and make a world feel bigger than it is. But for your own, behind-the-scenes knowledge, you’ll want to work backwards, asking yourself questions about the kind of world in which your little details could exist. I can’t find a source for this so I could be wrong but I swear I read once that Frank Herbert figured out a lot of the tech for Dune just because he wanted to have swordfights in his far future science-fantasy tome. Ask yourself questions and you’ll find the answers are usually pretty interesting. I actually prefer this way of working out a setting to starting with a big picture and extrapolating the details from that- it’s hard to figure out every possible consequence of your initial choices. But both ways work!

I do this sort of question-and-answer, working-out-the-logic-and details of a setting in handwritten notes and doodles in a real cheap notebook. Keeps everything loose and low-pressure. I can cross stuff out, I can write stuff in the margins, I can make maps and character sketches all in one spot and don’t have to worry about anything being perfect. It’s very liberating. Some people may prefer other methods. Whatever presents the smallest barrier to you, you know, actually taking the time to write out the setting, is the best method for you.

As for coming up with worldbuilding ideas- just steal them. Now obviously I don’t mean plagiarize someone else’s work. I mean don’t be afraid to make your influences obvious- if that’s what you like, then that’s what you like! There’s a good Tom Parkinson-Morgan (KSBD, Lancer, Icon) quote that gets to the heart of what I’m trying to say here:

“I think that my influences are pretty on my sleeve but I like to think I do at least a decent job of amalgamating them into something original” [source]

The more you work on something, the more it becomes your own, even if you’re taking heavy, heavy influence from others. So much of ATLA was obviously sprung from the creative team’s interest in Ghibli movies and the Century of Humiliation/East Asian historical geopolitics. Book of the New Sun has clear references to H. G. Wells and Jack Vance. Hyperion features the Martian “John Carter Brigade” and a hacker named “Cowboy Gibson.” The influences are obvious but the worlds still feel real, alive, and not at all derivative.

A last point that might be helpful- a good understanding of genre conventions and the history of the genre in which you’re working can be invaluable. I heard a good take to the effect that the more established a certain convention is within a genre, the less suspension of disbelief (and, consequently, the less explanation) is necessary for the reader. So, for example, if you’re writing a space opera, you really don’t need to explain why there are spaceships and ray guns (although it’s always helpful if you, the creator, know the answer to that why question). Similarly you don’t need to explain the presence of elves and dwarves in high fantasy- they’re there, people expect them. It’s the unique things that will require an explanation, and how you go about explaining them I’ve already outlined above.

Some personal world building gold standards are:

Avatar: It just gets everything right

Evangelion for the way it works with genre conventions, makes them feel even more believable (all the work that goes into showing the massive resource and manpower investment into making the EVAs work), and then subverts them

Hyperion / Fall of Hyperion for synthesizing basically all the major subgenres and literary movements of 20th century sci-fi and then telling a kick-ass story with the world it builds out of them (negative points for retroactively ruining everything in Rise of Endymion)

Anyway, hope this helps and if anyone has some notes or criticism for me, please let me know! I’m really not much of a writer, I just read and draw a lot.

101 notes

·

View notes