#Bayet fossils

Text

Cephalopod Fossils from Lyme Regis, England

My position as a Research Volunteer in the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology (IP) allows me to delve into stories about the collection that I find interesting. One of my research assignments is to investigate the fossils from Lyme Regis, England. The Lyme Regis fossils are part of the 130,000 specimens purchased by Andrew Carnegie from the Baron de Bayet of Belgium in 1903. Some of the Bayet fossils are incorporated into the museum’s Dinosaurs in Their Time (DITT) in the Triassic, Jurassic, Cretaceous, and a special Lyme Regis case that showcases 13 invertebrate and vertebrate fossils.

The village of Lyme Regis is situated on the Dorset Coast, and as such, receives some of the worst weather associated with the English Channel. The Lyme Regis cliffs and beaches have been a fossil hunting graveyard for two hundred years, first made famous by resident Mary Anning (1799 – 1847). When she was just twelve years old she found a large skeleton of a marine reptile known as an Ichthyosaur (literally “fish lizard”). Ichthyosaurs were predators that fed on Jurassic fishes and ammonites. It’s easy to see how she developed a love of fossils after discovering such a magnificent creature as a child. For years, she amassed collections of plesiosaurs, pterosaurs, fish skeletons, and other marine fossils and sold them for a living to paleontologists worldwide. In DITT, there are two examples of Ichthyosaur specimens, a skull (CM 877) and a three-foot-long skeleton (CM 23822). Unfortunately, Mary Anning was not recognized during her life for her accomplishments, probably because she was not a trained paleontologist and she was female. After her death, the collections became widely known to the scientific community, bringing about a better understanding of the paleontology of the Dorset coast.

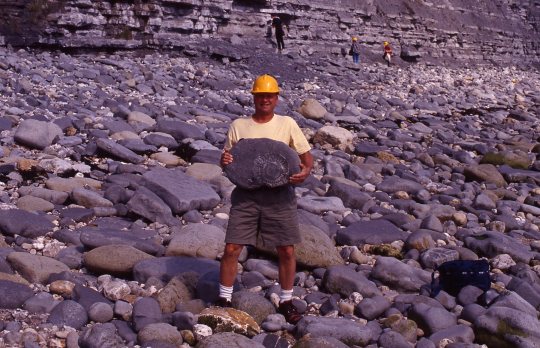

A fascinating piece of trivia about Lyme Regis is the filming of the 1980 movie, The French Lieutenant’s Women, which depicts the lead male actor, Jeremy Irons, using a simple rock hammer to extract a fossil ammonite from the cliff. If only it was that easy to collect from the 300-meter sheer cliff. My supervisor, Albert Kollar, collected fossils along the Lyme Regis beach in 1999. He opined “most fossils are eroded naturally because of the storm waves coming in from the English Channel that eat away at the rock each year, collapsing to the beach in broken blocks that eventually expose the fossils over time.”

My project was to research the Lyme Regis mollusks i.e., ammonites, nautiloids, and belemnites, update their identification, and review the climate aspects of the Jurassic sea that once covered this part of Europe approximately 199 to 190 million years ago. Paleontologists use marine fossils to interpret past paleoclimates and the paleoenvironments in which the animals once lived. The Jurassic is commonly considered as an interval of sustained warmth without any well-documented glacial deposits at the polar regions. The Lyme Regis fossils are preserved in very discrete layers of limestone strata often named “Lias” by European geologists. The terminology used today is early Jurassic Sinemurian Stage. The fossil mollusks are singular specimen’s that measure approximately 1 inch to 8 inches in diameter. The Carnegie of Natural History collection contains 16 invertebrate specimens from the genera Acanthoteuthis, Asteroceras, Eoderoceras, Liparoceras, Lytoceras, Microderoceras, Nautilus, Radstockiceras, and Xipheroceras.

All Bayet fossils were recorded in the Carnegie Museum Catalog of Fossils. The Cephalopod Catalog contains ammonite, nautiloid, and belemnoid fossils assigned by Bayet and includes details such as collection localities and stratigraphic horizon. Some Lyme Regis specimens are recognized by having two letters “BK” and a painted number, as seen on CM 40666. In 1975, a Swiss paleontologist, Dr. Felix Wiedenmayer, was on a research sabbatical to study fossil sponges at the Carnegie Museum, as well as an expert on Mesozoic ammonites from Europe. He reviewed many Mesozoic ammonites providing updated identification to genus and species, and stratigraphic horizon data, including some of the Lyme Regis ammonite fossils.

To complete the project, I created a virtual geology, paleontology, and exhibit folder in PowerPoint. This includes photographs of the specimens, a geologic map of Lyme Regis and the Dorset Coast, a Paleogeographic map, the distribution of genus and species in the collection, and references. The photographs in this study were taken by IP Research Associate/volunteer John Harper.

I have had a great experience at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History gaining knowledge about these fossil collections, stratigraphy, and geologic time. Now, I look forward to graduate school in part to study microfossils that lived in the seas during a climate “event” around 56 million years ago during the Paleogene Epoch. This event is called the “Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum” (PETM), and is so named because it demarcates the boundary between these two epochs of geologic time. It has been a pleasure looking at these exceptional cephalopods at the Carnegie Museum, and I look forward to any more potential collaborations in the future.

William Vincett is a research volunteer in the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology and a graduate student at the University of Delaware. Museum employees and volunteers are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Invertebrate Paleontology#Lyme Regis#Bayet fossils#Carnegie Museum Catalog of Fossils#Fossil#Fossils

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Fossils#Paleontology#Invertebrate Paleontology#Fossil Collection#Ernest Bayet

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Student of the World:

Part 2: Stearns and Bayet

by Joann Wilson and Albert Kollar

“His [Frederick Stearns] love for that which was beautiful and useful, led him to collect a vast amount of material covering so many fields of human effort…”

Detroit Free Press, January 15, 1907

Fossils pass through many hands. Some hands hold discoveries, some buy and sell, others study and organize. Behind every fossil is a story and hopefully, for those in museum collections, a specimen label. With luck, the geology and paleontology of the label script is accurate. Beginning with the creation of the first color geological map by William Smith in 1815 and the subsequent organizing of the Geologic Time Scale in 1823, paleontologists worked to validate stratigraphy by collecting and describing new species from exposed strata in Europe and North America. It was not until the publication of Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species in 1859 that paleontological work shifted to include studying evolution as documented by fossil evidence.

Today we understand that many hands aided fossil discovery, often in anonymity. Thanks to technology and through a focus shift to the individuals behind the specimens, we can now provide a fuller picture of the past that acknowledges the roles of collectors, dealers, indigenous cultures, women, quarry workers, and all who aided in the pursuit of fossils.

In the basement of Carnegie Museum of Natural History, behind a set of gray steel doors in the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology, is an astonishing assembly of archival documents from the Bayet Collection. Andrew Carnegie made front page news in 1903 by purchasing an estimated 130,000 fossils from Ernest Bayet of Brussels. Along with the fossils, the museum also received hundreds of documents written primarily in French, German, and Italian. Most of it has remained untranslated, until now.

Thanks to volunteer Lucien Schoenmakers of the Netherlands, details of fossil trades and purchases from over 100 years ago provide links to narratives that have yet to be told. Join us as we start the journey. Our series, which began with an examination of correspondence between fossil collector Frederick Stearns and his client, Bayet, continues here with a deeper profile of Stearns.

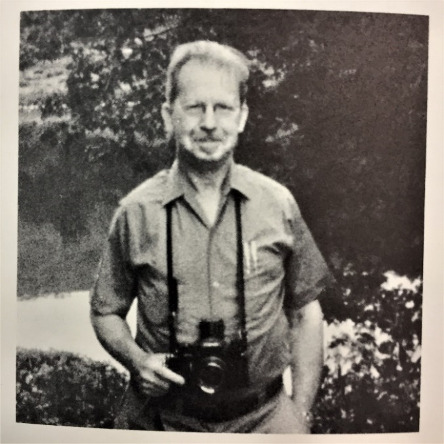

Frederick Stearns, date unknown. Permission of the University of Michigan Stearns Collection.

Frederick Stearns of Detroit was a man not born into wealth, but with a passion for education, art, and science. His early life revolved around diligence, not fossils. Born in Lockport, New York in 1831, Stearns quit school at age 14 to find a job. Within a year, he found work as an apprentice to a pharmacist in Buffalo, New York. Of his early life, he later said, “one of my earliest memories is looking into the windows Dr. Merchant’s Gargling Oil Drug store and wondering at the mystery of the white squares of magnesia and the round balls of chalk.” Eventually, Stearns moved to another pharmacy, and became partner, but he was not convinced that Buffalo, New York was his ticket to success.

On a frosty New Year’s Day in 1855, Stearns, newly married and just 24 years of age, crossed the frozen Detroit River by foot to start anew. Of that period, he later said, “little money, fair credit, high hope.” He opened a retail pharmacy in Detroit. To reach customers, he made short trips to the surrounding area, leaving samples of his products. Over time, his business expanded to the manufacture of pharmaceuticals. In 1877, he made history by installing the first telegraph line in the city of Detroit. But despite the success, Stearns dreamed of the education lost to him when he left school at the age of 14. In 1887 at age 56, he turned the business over to his sons and he began to travel the world. Over the next twenty years, he collected many items, including fossils.

William Smith's 1815 Color Geological Map.

Stearns pursuits led him to Africa, Europe, and Asia. In the late 1800’s, a voyage to Japan required weeks of travel as compared to a current 14-hour flight from New York to Tokyo. In the early 1890’s, Stearns travelled to Japan twice for the purpose of studying mollusks and other marine life. In a book published in 1895 titled, “Catalog of the Marine Mollusks of Japan,” Stearns credits Japanese fisherman Morita Seto for assisting in the collection of over “1000 forms of marine life.”

But Stearns interest did not stop with mollusks. He also collected fossils, art, and musical instruments. His collection of musical instruments at the Stearns Collection of Musical Instruments at the University of Michigan, in Ann Arbor Michigan, is considered one of the finest in the world.

For a short time, Stearns also collected fossils. Between 1888-1889, he wrote two letters to Ernest Bayet about a trade deal. Stearns first letter offers a clue as to how they met. Both men appear to have known fossil dealer Lucien Stilwell of Deadwood, South Dakota. The trade between Stearns and Bayet did not go smoothly, but it does have a happy ending.

Stearns was a student of the world until the very end. In 1907, just days before he was scheduled to sail for Egypt, he became ill and died. At his passing, the Detroit Free Press wrote, “A remarkable phase of Mr. Stearns’s activities as a collector was their diversity… and all of this for the simple love of learning things that he might tell them to others without price.”

Many thanks to the generous contributions of Carol Stepanchuk, Outreach and Academic Projects at the U-M Stearns Collection of Musical Instruments Lieberthal-Rogers Center for Chinese Studies and Joseph Gascho, Associate Professor at the University of Michigan School of Music and Director of the Stearns Collection of Musical Instruments. Many thanks to volunteer Lucien Schoenmakers’ ongoing effort to translate archival Bayet documents written in French and German.

Joann Wilson is an Interpreter in the Education Department at Carnegie Museum of Natural History and Albert Kollar is Collections Manager for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Fossils#Invertebrate Paleontology#Paleontology#Frederick Stearns#Ernest Bayet

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Behind the Scenes with the Baron de Bayet and L. W. Stilwell Collection, Part 4: Buying and Selling Fossils in the 19th Century

Figure 1: Letter from Stilwell to Bayet, June 29, 1897 (Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Section of Invertebrate Paleontology)

In this, our fourth and final installment, we will look at the Stilwell-Bayet letters. Because letter writing was the central form of communication in the late 19th century, this correspondence documents past collecting practices. Although the Carnegie Museum’s Bayet archive retains only Stilwell’s part of the correspondence, the letters provide insight into their business relationship.

Procuring Fossils Was Time Consuming and Expensive

In June of 1897 (Figure 1), Lucien W. Stilwell wrote, “In reply, I am glad you are pleased with the Fossils. As to their getting there a little late, I did all on my part and cannot be made to suffer in any way for lateness. Had you ordered earlier and hand [sic] not correspondence been necessary previous to my shipment, I would have sent them earlier.” Shipping was labor intensive and costly in the late 1800’s. Additionally, the risk of breakage was high. The trip from South Dakota to Brussels required multiple carriers and involved wagons, trains and ships. From start to finish the trip could take months. One Stilwell receipt dated January 12, 1889, shows the cost of shipping two boxes from New York to Brussels at $5.05, or about $141 today. Keep in mind, this figure does not include the cost of shipping from the Dakota Territories to New York.

Negotiating Was as Wild as the West

Deal making was a delicate dance. Stilwell wanted to maximize profit. Bayet wanted the best price. In March 1889 Stilwell states “I do not know what new animal you spoke of. I sent the new ammonite. As to shipping and getting them away across the ocean, before we agree on price, that is a rather indefinite way and might be an expensive thing. I can say now, that if people do not want to give what I ask for these heads [Cenozoic mammal heads], I do not care to collect them for when I base my prices on the cost of finding and cleaning them and the cash expense and place them as reasonable as anyone can afford to do the work then I would cease to collect them.”

Let the Buyer Beware

Sometimes, lines were crossed. In addition to invertebrates, Stilwell sold Bayet Cenozoic mammal fossils from the Badlands. Stilwell references a mammal skull in the quote above. In 2004, Spencer Lucas of the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, wrote a paper titled "O.C. Marsh and the Eocene Brontothere Teleodus: A Paleontological Hoax. In it he describes negotiations between paleontologist O.C. Marsh and Lucien W. Stilwell. Lucas concludes that Stilwell, or someone in his employ, added extra teeth to a brontotherium skull in order to induce Marsh into paying a higher price. At that time, Marsh did not notice that the teeth were doctored. According to Lucas, Marsh was determined to have the skull at the lowest possible price. He convinced Stilwell that the skull was not a new species and Stilwell eventually sold him the skull for a reduced figure. The altered teeth were not discovered until 1982 by Lucas and Schoch. Lucas concluded in 2004 that, “The Teleodus avus hoax is yet another example of the authenticity problems inherent to the commercial purchase of fossils as well as the great capacity all paleontologists have for seeing what they want to see in a fossil, not what actually is there.”

Albert Kollar notes that to his knowledge there is no indication that any of Bayet’s invertebrate specimens were fabricated or distorted.

The Stilwell-Bayet Correspondence is a fascinating look at collecting and negotiating in the “Wild West” a century ago. Preparation of fossils for shipping was time consuming and risky. Rarity and preservation quality often dictated price and it was a “buyer beware” marketplace. The items in the Carnegie Museum of Natural History collections give a glimpse into the mores, history and values of a past business climate. Stories, such as this one, also provide an opportunity to think about the future. One wonders what collecting adventures, conducted by museum scientists today, will resonate with future generations and what conclusions they may draw.

Joann Wilson is volunteer with the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology and Albert Kollar is Collections Manager for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Century Ago, a Donor Walked into the Carnegie Museum

Figure 1: Accession #6163, Donated By Major J.P. Young

What could have inspired someone to arrive at the Carnegie Institute, on a cold winter day to donate a small collection of fossils found while serving in World War I, less than a month after returning to the United States?

Albert D. Kollar, Collections Manager for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, discovered this mystery while undertaking a multi-year project to take a fresh look at the Baron de Bayet Collection, a collection of 130,000 fossils purchased by Andrew Carnegie in 1903. While looking at the trilobites, an extinct group of arthropods, Albert noticed a few specimens missing the characteristic “BH” letters and/or labels that typically identify the Bayet collection. After some detective work, Albert uncovered evidence of a previously unknown collection, “a small collection of fossil shells,” from France, that had been donated by a “Major J.P. Young” in 1919. (Figure 1).

Major Young, born in 1873 in Middletown, Ohio, developed a love of collecting early in life, spotting artifacts from indigenous cultures of North America, while working as a surveyor, for the Pennsylvania Railroad. His connection to Pittsburgh was further strengthened by his marriage to Margaret Young Oliver, daughter of George T. Oliver, industrialist and United States Senator from Pennsylvania. After World War I, John and Margaret settled in Ithaca, New York, where John was affiliated with his alma mater, Cornell University, for the remainder of his life. From 1925-1935, he painstakingly illustrated eight volumes of diatoms, single celled algae with sharp exterior coatings made of silica. Many of these illustrations were published by Dr. Mathew Hohn in 1951. During World War II, John Young volunteered as a “dollar a year man;” so that a Cornell staff member could serve in the war effort. After the war, he returned to his fascination with indigenous artifacts when he reorganized the Seneca and Cayuga collections of the DeWitt Museum in Ithaca, New York. But his longest tenure of service involved the Cornell Paleontological Research Institution (PRI), which he joined in 1934. He served as president from 1941-43 and remained active until his death in 1957. Fellow members of the PRI described him as “scholarly and pleasant” in a memorandum published after his passing.

Which brings us back to those fossils. In 1917, at age 44, John Paul Young joined the United States Army, and was tapped to lead the 5th Trench Mortar Battalion, a unit of 600 soldiers. Sometime between September and November of 1918, while managing his soldiers’ cold, thirst, hunger, and conditions such as “trench foot,” a complication from extreme wetness and cold that could turn a soldier’s foot into a gangrenous mass, Major Young may have noticed fossiliferous rocks at the bottom of a trench along the Western Front in Vitrey-sur-Mance, France (Figure 2). Intrigued to find fossils in a trench, the Major collected and then later donated them to the Carnegie Institute in 1919.

Figure 2: French Locations of Carnegie Trilobites

This fall, Albert travelled to Paris to visit the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle in Paris seeking to uncover this 100-year-old French trilobite mystery. Albert met with Dr. Sylvain Charbonnier, Collections Manager of Invertebrate Paleontology at the Muséum to discuss this puzzle. Albert’s query is to verify the genus, species, age, and stratigraphic locality of these trilobites. At this point, his preliminary research indicates that the Bayet trilobites are distorted and preserved in a black siltstone rock, that Albert recently coated with a white salt to enhance the fossil detail (Figure 3). In contrast, the three trilobites without labels possibly attributed to Major Young (see Figure 4) are also distorted; but preserved in a brown iron color siltstone. The iron oxide coating gives them a reddish appearance. They too are coated with a whitish salt to enhance detail.

Figure 3: Sample of a Bayet Trilobite from Vitré

Figure 4: Trilobites From Major Young Donation

An established paleontological collecting method, crucial to the identification of specimens, is to know the exact placement of the fossil to the stratigraphic locality (rock layer) which can support a known geologic age verified in the Geologic Time Scale. If someone makes a collection, such as the Baron de Bayet, and a paper label is preserved (Figure 3) then, Albert must confirm through paleontology literature and the geologic map of France, all known stratigraphic localities in the region for evidence of similar trilobites. For example, the Vitré label in Figure 3, establishes the location for this trilobite as Bretagne in the northwest of France. To ascertain the proper locality of the Major’s donation (Figure 4), we assume at this point, that it is from Vitrey-sur-Mance in the northeast of France; but further research is planned to resolve the exact location of the of the trenches that the Major occupied in World War I.

Following the advice of Dr. Charbonnier, Albert will proceed to digitize all 50 plus trilobites and send these images and other documentation to the Paris Muséum for further review. While we await the results, the fact that the fossils are sparking a new vein of research is probably exactly what the Major had hoped for all along.

Joann Wilson is the Interpreter for the Department of Education and Volunteer for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology at CMNH and Albert Kollar is the Collections Manager for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Many thanks to the fabulous Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh staff, with special acknowledgment to Carnegie Museum Library Managers, Xianghua Sun and Marilyn Cocchiola Holt, and Carnegie Reference Librarians Joanne Dunmyre and Leigh Anne Focareta. Special thank you to Peter Corina at the Kroch Library, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections at Cornell University.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Invertebrate Paleontology#Bayet Collection#Trilobites#Fossils#Carnegie Institute

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Behind the Scenes with the Baron de Bayet and L. W. Stilwell Collection, Part 2: The Wild West a Century Ago

Figure 1: Deadwood, Dakota Territories 1879. Image courtesy of the Deadwood Historic Preservation Commission, City of Deadwood Archives.

Figure 2: Deadwood, Dakota Territories 1879. Image Courtesy of Deadwood Historic Preservation Commission, City of Deadwood Archives.

Fancy yourself on the hottest day in summer in the hottest spot of such a place without water — without an animal and scarce an insect astir — without a single flower to speak pleasant things to you and you will have some idea of the utter loneliness of the Bad Lands.” Thaddeus Culbertson, 1850

When Lucien Stilwell stepped off the stagecoach on September 25, 1879, he was not your typical visitor to Deadwood. Photos of Stilwell in later years show a thin scholarly figure with glasses. In 1879, Deadwood, Dakota Territories was known for gold prospecting, gambling and lawlessness. Just three years prior, Wild Bill Hickock had been shot in the back while playing poker here. It would be a few more years until Seth Bullock, first sheriff of Deadwood, would begin to bring order to town.

As Stilwell stepped off the stagecoach, he was leaving a fifteen-year career in the grocery and grain business in Cairo, Illinois. A yellow fever epidemic blanketing parts of the United Sates prompted him to uproot his life. He arrived just one day before a fire destroyed over 300 buildings and displaced over 2000 people in Deadwood. According to Michael Runge, City Archivist of Deadwood South Dakota, photos of Deadwood in 1879 (Figures 1 and 2), were taken just before the great fire. If you look closely at Figure 2, you can see a law office, hardware store, liquor store, and city market.

Despite the great fire and the dangers of Deadwood, Lucien W. Stilwell found a job at a bank, brought his family to town and built a home. Along the way, he became fascinated by the fossils in the surrounding Black Hills. He began a careful study of the region and developed relationships with other fossil collectors. Eventually, he turned his hobby into a side business.

Figures 3 & 4: CM 33067 - Baculites collected by Stilwell. Baculites, translated as “walking stick rock”, are an extinct group of straight cephalopods that swam the seas 75 to 80 million years. “Sutures” or growth lines are formed when the animal adds new shell material as it grows. Sutures assist paleontologists in the identification of the genus and species.

Prior to leaving the bank in 1890, Stilwell began selling Badland fossils and minerals. In a correspondence to the Baron de Bayet of Brussels dated January 12, 1889, Stilwell said, “I tried to catch your meaning in your last letter. As I understand it, you wanted one of every specie and variety of fossils I had, excepting the large and costly specimens of mammals.”

In one letter to Bayet, Stilwell wrote, “I put in a number of baculites, all of which have some different interest. One is to show fine sutures another to show iridescence to rare degree, another to show size, another to show form so differing as to be a specie of baculite by another name…” Albert Kollar of the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology explained that in circumstances when the exact stratigraphic locality is questionable, having the original fossil labels as seen in Fig. 4 are critical to accurate fossil identification. Stillwell was a capable researcher because of his grasp of the geology and paleontology of the Badlands region. Figures 3 and 4 show a baculites sold by Stilwell to Bayet. There are 100 Stilwell fossils in the 130,000 specimen Bayet collection.

The next post in this series will explore why dealers such as Lucien W. Stilwell, found so many fossils in the Badlands.

Many thanks to the generous assistance of Michael Runge, Archivist for the City of Deadwood, South Dakota.

Joann Wilson is an Interpreter for the Department of Education and a volunteer with the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology. Albert Kollar is Collections Manager for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Baron de Bayet#Fossils#Badlands#Invertebrate Paleontology#LW Stilwell#Baculites#Paleontology

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bayet’s Bounty: The Invertebrates That Time Forgot

Albert Kollar, Collections Manager for the Carnegie Museum of Natural History Section of Invertebrate Paleontology, is on a mission to re-examine the Bayet Collection, a collection of 130,000 invertebrate and vertebrate fossils brought to the Carnegie more than 100 years ago. Albert is re-examining the invertebrate portion of the Bayet (pronounced “Bye-aye”), which as it turns out, is 99.9% of the collection.

The story starts with a last-minute trip that began on July 8, 1903 by Carnegie Director William Holland, who had received word of a world-class fossil collection that had been put up for sale in Europe by the Baron de Bayet, first secretary to King Leopold II of Belgium. Holland immediately booked passage to Europe on the steamer “New York” to complete the deal. At stake were 130,000 invertebrates, combined with a small number of vertebrate fossils (several on display in the Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibition), sought by museums throughout Europe, Great Britain and the United States. This collection became the largest addition to the department of paleontology at the Carnegie Institute, since the discovery of the dinosaur Diplodocus carnegii, at Sheep Creek, Wyoming in 1899.

Mr. Carnegie personally wrote a check for $25,000 for the project, a sum so large it exceeded the entire 1903 budget for all art and natural history acquisitions combined. Eventually, Mr. Holland negotiated a price of just under $21,000 with the Baron de Bayet for the entire collection. Another $2,300 was spent to pack, insure and transport everything back to Pittsburgh. Twenty men and women worked for three weeks to meticulously wrap each fossil in cotton, batting, or straw and by September 1903, two hundred and fifty-nine crates arrived safely in Pittsburgh. Storage of the crates was an issue, since the Carnegie Museum building would not be completed until 1907; so Mr. Holland rented space in a warehouse on 3rd Street in Pittsburgh for storage of 210 of the 259 crates.

This decision, however, almost destroyed the collection when a fire broke out on the upper floors of the 3rd Street warehouse. On December 30, 1903, Mr. Holland wrote, “Yesterday brought with it a fire in which it appeared as if the Bayet collection, the acquisition of which we had so prided ourselves, was destined to go up in smoke.” Fortunately, the Pittsburgh Fire Department contained the fire to the upper floors and the Bayet collection, stored on the lower floor, and meticulously wrapped and crated, survived with minimal damage. The crates returned to the Carnegie Institute to dry out.

In early 1904, William Holland hired Dr. Percy Raymond, a graduate of Yale University, to be the first curator of Invertebrate Paleontology. His primary directive was to catalog and organize the Invertebrate portion of the Bayet collection. Today, over 100 years later, Albert Kollar with the help of Pitt Geology student E. Kevin Love, is undertaking a multi-year project to translate Percy Raymond’s beautifully hand-written catalogs and to migrate all 130,000 specimens into a new database.

Pictured below is (BH1) the very first Bayet specimen cataloged by Percy Raymond. BH1 is an exquisite 510-million-year-old, CM 1828 Paradoxides spinosus, a 17.17 cm or 7” long trilobite from Skreje, Bohemia – or the Czech Republic of today.

Albert’s goal in revisiting the Bayet collection is to better understand the great history of the how, why and where of fossils collected in the late 19th century, especially in Europe the birthplace of paleontology and geology. “This project will give us insight into why certain Bayet fossils were recovered from classic European fossil localities, many of which are designated stratotype (significant geologic time reference) regions. These fossils and localities have been used to document the validity of evolution, extinction, and the Geologic Time Scale over the last 100 years. With an improved database, we hope to better appreciate the scientific value of the entire collection and create new statistical measures for future research and education.”

When asked if he expected any surprises as we go forward, Albert smiled, “Not until all the data has been analyzed will we have an opportunity to review the collection’s full scientific worth.”

Check back in a few months, Bayet’s invertebrates may have a few secrets yet to share.

Many thanks to Carnegie Museum Library Manager, Xianghua Sun for help researching this post.

Joann Wilson is an Interpreter in the Education department at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Bayet#Invertebrate Paleontology#Fossils#Stratotype#Paleontology#Geology#William Holland#Andrew Carnegie#Pittsburgh

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meet the Fossil Detectives in the Basement

by Suzanne Mills and Albert Kollar

Gray metal storage cabinets march in rows across the concrete floor. The collection space has no windows and there is a constant hissing sound from the overhead air ducts. No matter, the staff is looking for clues of the geologic and paleontological past, or History of the Earth, through the vast collection of fossil invertebrates. The staff and volunteers of the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology (IP) is tasked to reorganize, preserve, and curate fossils through the leadership of the Collection Manager Albert Kollar.

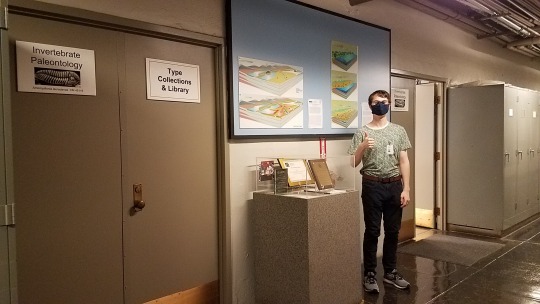

Collection Assistant Kevin Love at the doors of the Invertebrate Paleontology section.

On any given workday, you’ll find us hefting drawers full of fossil-bearing rocks and playing specimen-box Tetris to make fossils fit in the available cabinet space. We examine century-old inventory books, search out (usually Google) maps to find absconded valuables (historical fossil sites), and decipher written scripts in unfamiliar French and German for valuable geologic data.

Long-term volunteers in IP include Rich Fedosick, a researcher assisting in the project to document the Carnegie building stones; John Harper, an expert on fossil snails taxonomy, Roman Kyshakevych, who is deciphering the famous Coppi collection from Italy; Tamra Schiappa, a paleontologist at Slippery Rock University who is updating fossil cephalopod identifications; and Vicky Sowinski, who performs collection support. Student researchers include collection assistant and graphic artist Kay Hughes, a 2021 Mount Holyoke College graduate who coauthored four peer-reviewed scientific publications produced by IP; and collection assistant Will Vincentt, who researched two Bayet collections, the Hunsruck Slate of Germany and Lyme Regis of England. Tara Pallas-Sheetz, a part-time assistant, has worked on various projects over the years.

Hear from some of our newest staff and summer volunteers in their own words below.

Lizzie Begley with large fossil corals

Name: Lizzie Begley

About me: B.A. Anthropology Penn State 2021; masters candidate in Museum Studies and Non-profit Management certification in progress at Johns Hopkins University

Why IP: Working “behind the scenes” in IP has helped me develop a better sense of what it looks like to work in a museum such as the Carnegie. As an aspiring museum professional, experience behind gallery floors is invaluable as I work to find my place in the field. For this experience I couldn’t be more grateful and, honestly, couldn’t be having more fun!

Katie Golden with fossil ammonites

Name: Katie Golden

About me: B.S. Biology, Juniata College 2023 (expected)

Why IP: When I was in preschool, I told people I wanted to be a paleontologist when I grew up. Here in IP, I like exploring a part of the museum that most people don’t get to see. I particularly enjoy puzzle-piecing together fossils that need repair. The intricate ammonites, trilobites, and insects preserved in amber are especially beautiful. My favorite fossil organism is Anomalocaris.

Tori Gouza with fossil corals

Name: Tori Gouza

About me: B.A. History and Anthropology, University of Pittsburgh 2023 (expected)

Why IP: I love working in IP. It is so exciting to be able to interact with others in the section and to learn what projects they are currently working on. Albert Kollar has encouraged not only discussion but also collaboration. It is great to converse with others who are passionate about their work.

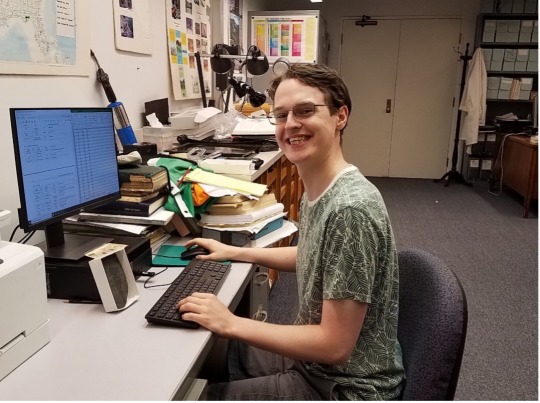

Kevin Love enters data about a fossil eurypterid

Name: Kevin Love

About me: IP Collection Assistant; B.S. Geology and Ecology & Evolution summa cum laude, University of Pittsburgh 2021

Why IP: I like solving puzzles at work. I find invertebrate fossils aesthetically appealing, but the main reason I like this job is that I get to understand little enigmas from Earth’s past. I like solving historical questions and compiling more information about fossils in the collection.

Suzanne Mills with fossil trilobite Isotelus gigas

Name: Suzanne Mills

About me: IP Collection Assistant, Professional Geologist, mom

Why IP: Every day is different when you work with a collection of 800,000 specimens. I may come across a 100-million-year-old ammonite sparkling with crystals inside, or a drawer full of trilobites acquired by the museum in 1903, when Andrew Carnegie was alive. I love that my work requires me to learn more about fossils which are beautiful, historical, and scientifically significant.

Ellis Peet with fossil crinoids

Name: Ellis Peet

About me: B.S. Environmental Geoscience with Geology concentration, Slippery Rock University 2021

Why IP: The management and staff of IP are smart, kind, personable, and they take paleontology seriously. I also like the environment at IP because it smells like a library and limestone dust, which reminds me of the geology department at Slippery Rock.

Joann Wilson with fossil trilobite Paradoxides spinosus from the Baron de Bayet collection

Name: Joann Wilson

About me: Interpreter for the Department of Education, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

Why IP: Fossils inspire awe. I enjoy unravelling the stories behind the individuals that discovered, studied and collected these breathtaking specimens.

Suzanne Mills is a Collection Assistant and Albert Kollar is Collections Manager in the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Natural History#Paleontology#Invertebrate paleontology#Fossils#Museum Work

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bayet and Krantz: 16 Words (Part 1)

by Joann Wilson and Albert Kollar

In June of 1903, William Holland, Director of the Carnegie Museum, seized a rare chance to acquire one of the finest private collections in all of Europe. The purchase was made with sixteen words. Within in Holland’s Archives at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History Library, on onion paper so fragile that it appears to float, is a carbon copy of the telegram that influenced the early history of the Paleontology Department. Mysteriously, only one name appears on this fateful cable, and it is not a name that you would expect. The name is “Krantz,” Dr. Friedrich Krantz of Bonn, Germany.

Dr. Friedrich Krantz sitting in the conservatory, or wintergarten, at his villa in Germany, (date unknown). Permission of Ursula Müller-Krantz, Executive Director, Dr. F. Krantz.

In 1859, Friedrich Krantz was born into a family that operated a geological supply business. In 1888, Krantz graduated with a PhD in geology from the University of Erlangen. That same year, he joined “Dr. A Krantz,” the company founded by his uncle, Adam August Krantz. By 1891, Friedrich Krantz took charge and changed the company name to “Dr. F. Krantz, Rheinisches Mineraliaen Contor.” The company continues operations to this day out of headquarters in Bonn.

Exactly when Ernest Bayet of Brussels and Friedrich Krantz met is uncertain. But thanks to the letters and fossil lists that arrived with the Bayet collection, we know that they corresponded at least three times. The difficult task of translating these documents into English is being handled by volunteer Lucien Schoenmakers, a resident of the Netherlands. Schoenmakers’ translation work here and with other records is contributing critical information to the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology’s multiyear project to fully document the invertebrate portion of the Bayet Collection.

From the archive, we know that Krantz visited Bayet at least once. On July 7th, 1897, Krantz wrote, “I intend to come to Brussels towards the end of next week and will be honored to visit you, I can use the numbered list to give you the exact individual prices for all the objects displayed by me.”

In fact, Bayet may have selected Krantz to act as his agent for the sale because he was so familiar with it. Krantz sold many museum quality specimens to Bayet; many with distinctive, elegant labels.

Encrinus liliiformis Miller (CM 29840): a Triassic crinoid from Brunswick, Germany with Krantz label.

The sale of Baron Ernest Bayet’s fossil collection to the Carnegie Museum in 1903, made front page news in the New York Times, and other papers across the country. In a letter to Andrew Carnegie, thanking him for allocating $25,000 for the purchase, an enormous sum for that time, Holland wrote, “We are never likely to have another such chance, and you have done a most splendid thing in securing it [the Bayet Collection] for our Museum of Paleontology.” That most splendid thing transpired, over a century ago, with just sixteen words:

“Carnegie Museum buys collection. Will pay cash price fixed by Krantz. If satisfactory, telegraph answer yes.”

Cable sent from Pittsburgh to Brussels on June 9th or 10th, 1903 offering to buy Baron Ernest Bayet’s fossil collection. “Krantz” refers to Friedrich Krantz of Bonn, Germany, a business man and fossil dealer who acted as Bayet’s negotiating agent.

Part 2 of this series highlights spectacular Krantz specimens within the Bayet collection.

Many thanks for the generous contributions of Ursula Müller-Krantz, Executive Director of Dr. F Krantz Rheinisches Mineraliaen Contor GmbH & Co., Marie Corrado, Carnegie Museum of Natural History Library Manager and Kelsea Collins, Carnegie Museum Library Cataloger. Continued gratitude to volunteer Lucien Schoenmakers’ ongoing effort to translate archival Bayet documents. Joann Wilson is an Interpreter in the Education Department at Carnegie Museum of Natural History and Albert Kollar is Collections Manager for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Invertebrate Paleontology#Paleontology#Baron de Bayet#Natural History

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

University of Michigan Helps Solve Century Old Fossil Mystery - Part 1: Stearns and Bayet. The Dispute

by Joann Wilson and Albert Kollar

“I am reluctantly, arriving at the opinion, that I am the victim of an imposition for which I hold you responsible.” -Frederick Stearns in a letter to Ernest Bayet, March 27, 1889

Frederick Stearns, date unknown. Permission of the University of Michigan Stearns Collection.

In 1903, Andrew Carnegie purchased the world-famous Bayet fossil collection for the Carnegie Museum. Since that time some invertebrates in the massive 130,000 specimen collection have been thoroughly studied, but the documents that arrived with the fossil shipment remained largely unexamined. Reasons for this neglect are understandable. The collection’s accompanying letters, lists, journals, and other documents were written primarily in French, German, and Italian, and in what has been described as “an impenetrable hand.”

Translation of the documents into English was a critical step in making them better known to researchers and the public. As part of Albert Kollar’s multiyear project to restudy the invertebrate portion of the Bayet Collection, that difficult task is ongoing thanks to volunteer Lucien Schoenmakers, a resident of the Netherlands.

The translated documents bring some life to the people behind the famous fossils, and our series begins with one of them, Frederick Stearns.

Which gets us back to the letter excerpted above. One wonders what Ernest Bayet thought in the spring of 1889 when he opened it. Bayet, who would become secretary to the cabinet of Leopold II, and Frederick Stearns of Detroit, Michigan, a retired pharmaceutical executive, business owner, and renowned fossil collector, had settled on a sizable trade deal. Stearns was to send over “1000 species of fossils” from the United States. In return, Bayet was to ship “5500 species of shells.”

One of the Frederick Stearns fossils in the Bayet Collection at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History: Horn Coral, Cyathophyllum, CM# 51102. On the bottom is an original Frederick Stearns label that survived crossing the Atlantic Ocean twice.

Stearns had shipped his lot of fossils, but by spring of 1889, he had yet to receive a shipment from Bayet. Fuming, he wrote, “to obtain legal redress through the advice of the American Minister at Brussels. Failing in this I stand ready to spend 2500 francs or even 5000 francs if necessary, to advertise you, and your way of doing things to the Scientific World. In doing which I shall at least have the satisfaction of check mating any similar future operations of the sort with other persons as credulous of your honor and integrity.” In current figures, Stearns was willing to spend $15,000-$30,000.

Stearns ended, “with this for warning, I subscribe myself indignantly etc.” After this letter, no more correspondence is known to exist between the two men. Did Bayet send his lot? As part of Albert’s project to investigate the individuals behind the Bayet Collection, we wondered, was it possible to solve this mystery over a century later?

Research into Stearns revealed that he collected more than fossils and shells. Carol Stepanchuk, Collection Outreach Program Coordinator for the Stearns Collection of Musical Instruments at the University of Michigan, provided a valuable starting point. With her guidance, and a hunch that Stearns may have left his other collections to the University of Michigan, we reached out across the Ann Arbor campus to Jennifer Bauer, Research Museum Collection Manager at the University’s Museum of Paleontology. Jennifer added Taehwan Lee, the museum’s Mollusk Collection Manager, to the search. After many months, our story has a happy ending. Jennifer and Taehwan located over 5000 specimens in the U-M collections, donated by Frederick Stearns, with “Bayet” as collector. Thanks to museum collections records and the amazing team at U-M, we now know that Ernest Bayet did send his shells!

In Part 2 of our series, we will take a look at the unusual path that brought Frederick Stearns into contact with Ernest Bayet and fossil collecting. As John Carter, former Curator of the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural history, once wrote about the Bayet Collection, “The best measure of the worth of this treasure trove, however, is not its size but its uniqueness. Many of the individual collections, all made in the nineteenth century, are essentially irreplaceable, because similar specimens from the same collecting localities are no longer available.”

Many thanks to the generous contributions of Carol Stepanchuk, Collection Outreach Coordinator for the U-M Stearns Collection of Musical Instruments, Joseph Gascho, Associate Professor at the U-M School of Music and Director of the Stearns Collection of Musical Instruments, Jennifer Bauer, Research Collection Manager at the U-M Museum of Paleontology, Taehwan Lee, Mollusk Collection Manager at the U-M Zoology Museum and volunteer Lucien Schoenmakers for meticulous language translation.

Joann Wilson is an Interpreter for the Education Department at Carnegie Museum of Natural History and Albert Kollar is Collections Manager for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

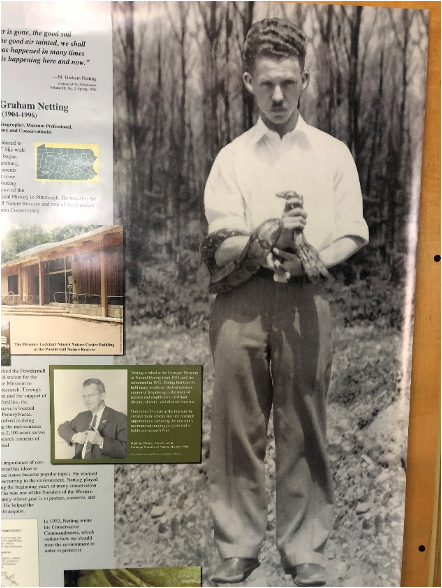

From Collector to Director

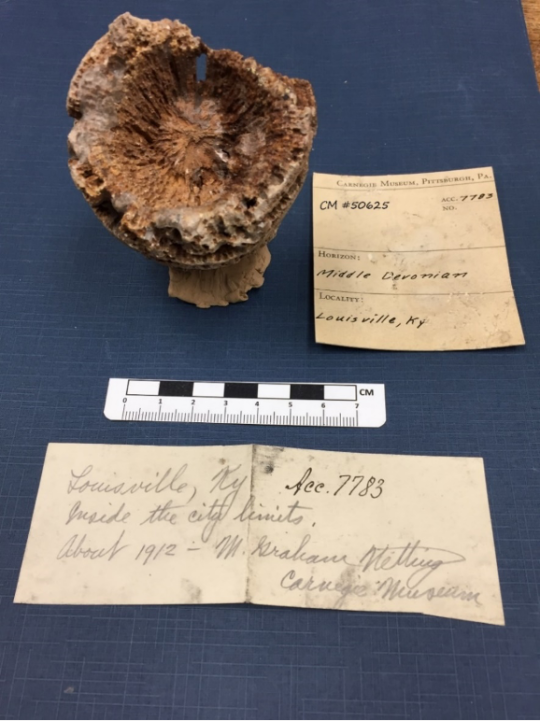

Figure 1: CM 50625 – Rugosa Coral. Collected by M. Graham Netting in 1912. Coral body shape has a radial symmetry.

In 1912, eight-year-old M. Graham Netting unearthed 13 coral fossils within the city limits of Louisville, Kentucky. Later, as a 22-year-old Pitt student, he donated them to the Carnegie Museum of Natural History (Figure 1). When the Great Depression cut short his graduate studies at the University of Michigan in 1929, he returned to the museum as Assistant Curator of Herpetology, and worked his way up to Curator in 1932. In 1954, six months before turning 50, he was appointed Director of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Along the way, the Wilkinsburg native left an astonishing legacy that includes a steady growth in scientific collections, numerous wildlife dioramas in the Halls of Wildlife, and a mid-Appalachian field research station, Powdermill Nature Reserve. Upon his retirement in 1975, the Post-Gazette noted, “Long before it was “in,” Netting saw pollution of the air and water ravaging the land.”

Albert Kollar, Collection Manager of the of Section of Invertebrate Paleontology, re-discovered young Graham Netting’s horn corals while working on a multiyear review of the Bayet Collection. Netting’s label note did not provide any evidence for the stratigraphic unit that he collected from, but more on that later.

Figure 2: Carnegie Museum of Natural History exhibit reconstruction of an Early to Middle Devonian reef, 375 - 390 MYA. The reef shows Rugosa and Tabulate corals, a spiny trilobite about 18 inches in length and several straight cephalopods. Coral tentacles (shown in white) are illustrated in feeding mode. Both Rugosa and Tabulate corals went extinct at the end of the Permian Period.

Rugose corals are often called horn corals because many species have a horn shape. Horn corals attach to the sea floor by way of a sticky tentacle that protrudes from the base or curved end of the animal. Other invertebrate animals, such as brachiopods, attached in this position are described as sessile. The coral animal or “polyp” built its skeleton from calcium carbonate, a mineral formed from Bicarbonate and Calcium ions in seawater. The polyp tentacles or feeding polyp extend out from the top of the basic body for feeding (Figure 2). When the animal died, its soft tissues would have decayed and left behind the external hard mineral skeleton that fossilized.

Netting’s Louisville coral specimens are fossilized in a different way than similar corals from the nearby Falls of the Ohio middle Devonian fossil beds. His corals are lighter and fragile to the touch, conditions which gave Albert reason to compare Netting’s fossils to similar invertebrate paleontology corals from strata within the Louisville area. Sometime during or after burial, these horn coral skeletons were replaced by silica or quartz, a process known as silicification. The mineral silica can saturate a column of seawater when the seabed is overwhelmed with a large population of sponges. Sponge skeletons are composed of silica and when they die silica is added to a column or more of seawater. Volcanic eruptions eject silica into the atmosphere that eventually settles into the sea. Again potentially adding higher amounts of silica. Whatever the cause, Albert believes Netting’s corals were collected from the fossiliferous Middle Devonian age Jeffersonville Limestone, where the “lower foot of a “conglomerate” of reworked silicified Louisville Limestone” of Upper Silurian age is known to occur with silicified coral fossils (Conkin and Conkin, 1972).

Horn and Tabulate corals thrived in shallow seas forming diversified ecological reefs from about the late Silurian Period to the beginning of the Late Devonian epoch. During the Middle Devonian epoch roughly 400 Ma to 390 Ma years ago, reefs formed in central New York, southern Ontario, central Ohio, central Iowa, western Alberta, Canada, western Australia, and in Eifel, Germany.

Figure 3: Paleogeographic Map of the Middle Devonian Period – Kentucky is well south of the equator.

Louisville, during the Devonian Period, was centered in the southern hemisphere about 40 degrees south of the equator. Because of plate tectonics, the coral beds of Louisville would travel 5,500 miles over the next 390 million years to their present-day location of 38 degrees north (Figure 3). Today, fossil outcrops in the city limits of Louisville are difficult to find.

Figure 4: Graham Netting in his twenties.

When Netting retired as Director of Carnegie Museum of Natural History, he moved to a modest house next to Powdermill Nature Reserve. A seat was saved for him each Sunday at the reserve’s weekly nature talk. In 1996, he passed away. Steve Rogers, Collections Manager for the Section of Birds, recalls sipping fresh lemonade on Netting’s back porch in 1981. According to Rogers, Netting was reflective and humble. The fossil collector who became a museum director had a habit of rubbing his chin while listening to someone speak. When asked about his legacy, Rogers replied, “He was more instrumental in forming Powdermill than anyone. He had an amazing ability to be a part of a team that got things done.”

Figure 5: Graham Netting at Retirement in 1975.

As Netting prepared to step down as director in 1975, he said, “These great collections are a natural resource to answer questions about the life of the world.” On a recent day, I saw two children jumping up and down in front of the Glacier Bear diorama in Hall of North American Wildlife on a family visit to the museum. When one of the children asked, “what’s a diorama?” I thought about Graham Netting, smiled, and encouraged their engagement with the life of the world.

Many thanks to Xianghua Sun, Carnegie Museum Library Manager, Marie Corrado, Carnegie Museum Library Clerk, Stephen Rogers, Collections Manager for the Section of Birds, and John Wenzel, Director of Powdermill Nature Reserve for help researching this post.

Joann Wilson is an Interpreter in the Education Department at Carnegie Museum of Natural History and Albert Kollar is Collections Manager for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Graham Netting#Wildlife diorama#Pittsburgh#Natural History#Powdermill Nature Reserve#Horn coral#Rugose coral#Louisville

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Behind the Scenes with the Baron de Bayet and L. W. Stilwell Collection Part 3: The Wild West Formed Million of Years Ago

Figure 1: Badland National Park Today, National Park Service photo, 2014. This view of the Badlands topography illustrates the erosion that took place over the last 2 million years.

The Lakota called the badlands “Mako Sica” or “land bad.” The early French-Canadian trappers referred to it as “les mauvais terres pour traverse” or “bad lands to travel through.” Seventy-five million years ago, this area was a lush underwater seaway filled with creatures such as mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, diving birds, fish, baculites, and ammonites (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Taxa that swam in the Western Interior Seaway from Dinosaurs In Their Time exhibit at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Photo by Patty Dineen.

The Stilwell fossils of Cretaceous age (Figure 3) were deposited in a black mud that accumulated on the sea floor from 82 to 70 million years ago (Figure 4). The Pierre Shale is part of the extensive Western Interior Seaway of North America (Figure 5). Museum visitors can view a changing geographic representation of the seaway on a wall-mounted flat screen monitor within the Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibit. The seaway extended from the Gulf of Mexico, Florida, and southern Gulf Coast, north through Texas, Kansas, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, the Dakotas, and the Canadian Provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan. This vast waterway terminated in the Artic region of Canada. At the time of the Pierre Sea, the ice sheet-free greenhouse to hothouse paleoclimate was much warmer than it is today, creating the highest sea levels in earth’s history. Sea level rises and falls were primarily controlled by the presence or melting of glaciers in the polar regions, the shifting of the continents, and the uplifting of proto-Rocky Mountains by plate tectonics.

Figure 3: Western Interior Seaway fossils on display at Carnegie Museum's Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibit. Stilwell fossils are highlighted in blue.

Figure 4: Outcrop photo of Pierre shale.

Figure 5: Western Interior Seaway approximately 75 million years ago. Red dot locates Deadwood, South Dakota today.

Fast forward to the Wild West of the 1890’s, and dealers such as Stilwell found and sold fossils to museums and private collectors. Knowledge of Badlands fossils spread as far as Europe, and by 1889 Bayet wanted some for his own collection.

Next, in our final post of this series, we will delve into the Stilwell-Bayet correspondence in search of clues about how fossils were bought and sold over a century ago.

Joann Wilson is an Interpreter for the Department of Education and a volunteer with the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology. Albert Kollar is Collections Manager for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Baron de Bayet#Invertebrate Paleontology#Paleontology#Wild West#LW Stilwell

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Behind the Scenes with the Baron de Bayet and L. W. Stilwell Collection, Part 1: Crossing the Atlantic with a Boatload of Fossils

Figure 1: Baculites fossil from the Bayet Collection with L. W. Stilwell label.

Why did a wealthy European baron seek out a Dakota Territories fossil dealer in the winter of 1889? This post is the first of a four-part series on renowned 19th century fossil collectors Baron de Bayet of Brussels and Lucien W. Stilwell, and their connection to the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Bayet assembled one of the great private fossil collections in Europe. In 1903, Andrew Carnegie bought the 130,000-fossil collection and had it shipped from the Port of Antwerp in Belgium across the Atlantic to the United States. The purchase garnered headlines in newspapers across Europe and in the United States and launched Carnegie’s fledgling museum onto the world stage. Thanks to the archival materials purchased by Carnegie as part of the Bayet deal, the relationship between Baron de Bayet and Lucien W. Stilwell provides a glimpse into how the Carnegie Museum of Natural History and other institutions built their collections. In part one, we consider what forces may have prompted Bayet to assemble a large collection of fossils in the first place.

The Pathway to Fossil Collecting Travelled Through the Principles of Stratigraphy and Geology

From the late 17th century until the early 19th century, collecting fossils was a hobby of gentlemen farmers and naturalists. Some of these collectors developed fundamental principles of geology and stratigraphy through observations and deductive reasoning, as to how rock layers, or strata, are formed, fully earning credentials as scientists. For example, in the 17th century physician Nicolaus Steno’s (1638 – 1686) observed simple patterns in strata during his walks through the hills of northern Italy. The four Laws of Stratigraphy he proposed are the law of superposition, the law of original horizontality, the law of cross-cutting relationships, and the law of lateral continuity.

The principles of stratigraphy were later interpreted by James Hutton (1726-1797), a Scottish geologist, to formulate his Doctrine of Uniformitarianism in 1785. This line of thinking assumed that the same natural laws and processes that currently operate in the universe had always operated in the universe and applied everywhere in the universe. Hutton’s Uniformitarianism included the gradualistic concept that “the present is the key to the past”.

William ‘strata’ Smith (1769 – 1835), considered the Father of Stratigraphy was a geologist and engineer who uncovered fossils from strata as he worked to build a water canal from Oxfordshire, England to the Thames River at London. In 1815 he made the first color geologic map of England, Wales, and part of Scotland, a document that developed from his identification of strata based on fossil taxa within the rock layers. His careful tracking suggested that fossil organisms, both faunas and floras, recorded in each geologic formation succeed one another in a definite and recognizable order, a principle summarized as the law of faunal succession.

Smith’s map led, in 1822, to geologists William Conybeare and William Phillips naming the Carboniferous Period for the younger (coal beds) and older (limestones) boundaries respectively for this ancient unit of geologic time. Because a single time period could not rest alone in any record of Earth history, the pioneering work of Conybeare and Phillips, Smith, Hutton, and Steno led eventually to the establishment of the Geologic Time Scale, a framework of three unimaginably long Eras, the Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic, for studying the evolution of life as preserved in the fossil and rock record over Earth’s 4.6-billion-year history. Within the Geologic Time Scale the Carboniferous Period is one of seven periods of the 290 million years that represent the Paleozoic Era.

As these principles of geology grew in acceptances, Charles Lyell (1769 -1875) an English field geologist who traveled extensively throughout Europe and North America, wrote a three-volume Principles of Geology (1830 – 1833), a work that Charles Darwin read during his Voyage of the Beagle (1831 – 1836). Darwin’s Theory of Evolution as written in his The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection – or the Preservation of Favored Races in the Struggle for Life circa 1859, was influenced by the geology and stratigraphy ideas put forth in the Principles of Geology.

Museums Emerged

Amateur fossil collectors such as Stilwell and Bayet perhaps recognized opportunities to supply and acquire fossils to satisfy demand for fossils by museums and universities across Europe and the United States. The first museum to become established in Europe was the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle in Paris, France in 1793, followed by the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin in 1810. Museums in Belgium, London and Austria followed.

In the United States, the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804 – 1806), mandated by President Thomas Jefferson, was the first U.S. government expedition to explore the unknown territory of the Louisiana Purchase in search of minerals, fossils, and indigenous artifacts. Co-led by Merriweather Lewis (1774 – 1809) and William Clark (1770 – 1838), the expedition collections were deposited at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, now known as the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University. Soon, other university museums came into existence such as “The Louis Agassiz Museum of Comparative Zoology", of Harvard University in 1859, and the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale University in 1866. The United States government established the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History in 1866. Before long, private institutions such as the American Natural History Museum in New York City, the Field Museum of Chicago, and Carnegie Museum appeared on the scene.

As museums hired scientific staff, rivalries between experts at different institutions developed. By the 1870’s, paleontologists Edward Drinker Cope, of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, and O.C. March, of the Peabody Museum at Yale University, began a two-decade competition to outdo each other in a battle to collect and name as many vertebrate fossils as possible. Their exploits are often referred to as “the Bone Wars” (Rea 2001). In 1874, O. C. Marsh arrived in the Dakota Territories. Word of the exotic sea creatures from the Western Interior Seaway and mammals from the Oligocene Period reached Europe, leading the Baron de Bayet to contact Lucien W. Stilwell for his assistance in acquiring “one of every species and variety.”

Next: Lucien W. Stilwell arrives in Deadwood Dakota Territories, a town known for gold, gambling and lawlessness.

Joann Wilson is volunteer with the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology and Albert Kollar is Collections Manager for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Invertebrate Paleontology#Baron de Bayet#James Hutton#Geologic Time Scale#Darwin#Natural History Museums#Nicolaus Steno

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

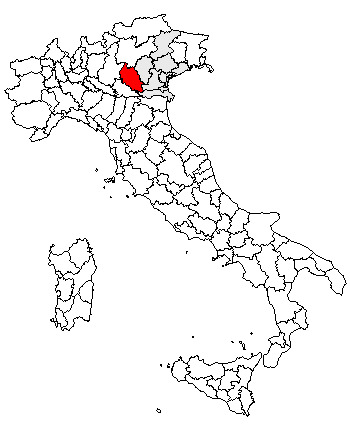

Preserving Fossil Treasures: Eocene Fishes from Monte Bolca, Italy

By Linsly Church

In 1903, Carnegie Museum of Natural History purchased an enormous private fossil collection from the Baron Ernest de Bayet of Brussels, Belgium. Over a 40-year period the Baron had amassed a collection comprising tens of thousands of individual fossils. At age 65 he married a much younger woman and sold the collection to fulfill her dream of having a house on the shore of Italy’s Lake Como. Within the collection are fossils from all over Europe. Fossils from Italy include the Monte Bolca fish collection, which contains about 290 beautifully-preserved specimens that date to about 50 to 49 million years ago, early in the Eocene Epoch.

The province of Verona (in red) in Italy, where the Monte Bolca site is located.

One quarry at Monte Bolca has been owned by the same family for almost 400 years. It is known as the Pesciara, meaning the fishbowl, because many of the marine fossils found there are those of fishes. Because the preservation is so good in some layers of limestone, the site is considered a Lagerstätte. A Lagerstätte is a site that contains exquisitely-preserved fossils, typically representing a diversity of organisms. At Monte Bolca, some fishes and other creatures have preserved internal organs and even skin pigmentation, the result of an anoxic (oxygen-poor) environment that hindered decay and scavenging. The fossil site also differs from most others in that it is an underground mine with tunnels instead of a typical open quarry.

Two of Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s most spectacular ~50 million-year-old fossil fishes from Monte Bolca, Italy. Top: specimen number CM 4369, belonging to the moonfish Mene rhombea. Bottom: specimen CM 4467, belonging to the spadefish Exellia velifer. Note the dark stains in the eye sockets, which are vestiges of the original eye pigments of these ancient fishes.

Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s collection of fishes from Monte Bolca is currently undergoing conservation. In the past, the museum’s Vertebrate Paleontology collection was housed on open shelves in rooms with poor air filtration systems, resulting in soot from the local steel industry building up on the fossils. In recent years, the museum has installed an HVAC system in the Vertebrate Paleontology collection rooms, which has greatly reduced the particulates that make it into these rooms and onto the specimens. In the years since these measures were taken, we in Vertebrate Paleontology have commenced a general cleaning of our specimens, starting with our fishes from Monte Bolca.

To clean the specimens, we use a soot sponge (or chemical sponge), which is also used by restoration companies to clean after fires. “Chemical sponge” is a slightly misleading name because there are no chemicals added to the sponge. It is made of vulcanized rubber and has tiny pores on its surface that collect fine soot particles without depositing chemicals on the fossil. Therefore, there is no need for water or additional solvents when using these sponges. Wet cleaning of soot can cause staining on the surface that is being cleaned so it is very important to use dry cleaning methods such as chemical sponges. In some cases, the soot on the specimens is so dense that it is obvious where cleaning has taken place.

Before and after: clean soot sponges, prior to use (top); dirty soot sponges, after use (bottom) (with the source of the soot—a newly cleaned fossil fish from Monte Bolca—in the background).

Evolution of a fish, roughly 50 million years after the fact. From top to bottom, the same fossil fish specimen from Monte Bolca (CM 4530, Carangopsis dorsalis) in four successive stages of cleaning.

Once the specimens have been cleaned, repairs are made as needed and labels are reattached if they are delaminating from (or falling off of) the specimen. Then, storage mounts are created for specimens as needed using archival materials. These materials are made specifically to be as neutral or inert as possible so as not to give off gases that could react harmfully with the specimens. Storage mounts are important because they reduce the amount of times someone needs to touch the specimen—which, in turn, reduces breakage—and protect the specimen from vibration when the compactors in which it is housed are opened and closed. These measures will help to protect the integrity of the specimens for years to come.

A drawer full of recently-cleaned Monte Bolca fishes in their new storage mounts.

Linsly Church is the curatorial assistant for the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

320 notes

·

View notes

Photo

About 130,000 unique and rare fossils from western Europe were purchased by Andrew Carnegie in 1903 from Baron de Bayet, executive secretary to King Leopold II (at turn of last century) Belgium.

Examples of fossils on exhibit in our core exhibition Dinosaurs in Their Time are from Lyme Regis (England), Holzmaden (Germany), and Solnhofen (Germany).

The fossils were collected from famous paleontology sites in Europe and United States more than a century ago.

257 notes

·

View notes